Age of the Aeronaut

The Dawn of Flight

Since the dawn of history, from the Greek myth of Icarus to the flying machines of Leonardo da Vinci, humankind has dreamt of flight. It was not until 1783 that dream became reality when Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier invented the globe aérostatique (hot air balloon).

Aeronauts were the first voyagers and navigators of flight. Ballooning made celebrities of aeronauts, whose adventures filled newspapers, sold books, and inspired works of fiction. Flight offered a sense of freedom and a radical new frontier for exploration.

Flights of fancy did not stop with ballooning, as inventors, engineers, and scientists devised navigable airships and early planes. The search for new modes of flight continues to propel science and the imagination today.

Flights of Fancy

![Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. de Montgolfier [Description of trials of the Montgolfiers’ aerostatic machine], Paris, 1783, Gift of the Burndy Library](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2faujas.jpg) |

![Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. de Montgolfier [Description of trials of the Montgolfiers’ aerostatic machine], Paris, 1783, Gift of the Burndy Library](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2faujas_39088006218994_0014_11_crop.jpg) |

Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. de Montgolfier

[Description of trials of the Montgolfiers’ aerostatic machine]

Paris, 1783

Gift of the Burndy Library

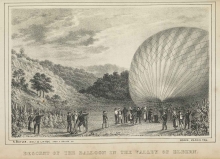

Inspired by watching clothes billow over an open fire and mindful of the British chemist Henry Cavendish’s discovery of hydrogen, the Montgolfier brothers experimented with fabric bags filled with heated air. Shortly after their successful ascensions with animal aeronauts, namely a sheep, a duck, and a rooster, Jacques-Étienne became the first person to take flight on the 15th of October, 1783 in a tethered balloon.

That same year, the first free-flight with humans took place on November 21st. Physics teacher and soon-to-be first victim of balloon travel Pilâtre de Rozier, and the French military officer François Laurent d'Arlandes ascended in a magnificent balloon from the park Bois de Boulogne. The historical event was witnessed by Louis XVI and thousands of enthralled onlookers, including Faujas de St. Fond, who documented the early history of ballooning.

I was astonished by the smallness of the noise our motion occasioned by our departure among the spectators; I thought they might be astonished and frightened, and might stand in need of encouragement, so I waved my arm with little success. I then drew out and shook my handkerchief, and immediately perceived a great movement in the yard.

--François Laurent d'Arlandes to Faujas de St. Fond, November 28, 1783

...I exclaimed to my companion Monsieur Robert—I’m finished with the Earth. From now on our place is in the sky! …Seeing all these wonders, what fool could wish to hold back the progress of science!

–Jacques Charles, after first balloon launch, 1783

No longer earthbound, the human spirit and imagination took flight. The age of the aeronaut was born. The new world of aeronautics became a seemingly endless frontier where adventure-bound aeronauts continuously made discoveries and pushed the boundaries of what seemed possible.

Scientific observation, adventure, and entertainment were all part of the story of ballooning. Thomas Baldwin’s introduction to ballooning included the first aerial views of earth. Baldwin’s subsequent account of his balloon travels, Airopaidia, was intended as an introductory manual to ballooning and aeronautics.

|

|

Airopaidia: Containing the Narrative of a Balloon Excursion from Chester, the Eighth of September, 1785

London, 1785

Gift of the Burndy Library

Always looking to improve the new field of aeronautics, restless and inventive minds turned their attention towards controlled aerial navigation. One of the earliest pioneers in aeronautics was the English engineer George Cayley.

At the close of the 18th century, Cayley put forth designs for a fixed winged flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control; similar to how the first modern airplanes would be designed. Cayley broke new ground in aeronautics at a time when science and the public questioned the future of flight as something more than a leisure activity. Cayley’s own inventions were not successful, but his work influenced ideas on practical flying machines.

|

|

"Practical Remarks on Aerial Navigation"

Mechanics' Magazine

London, 1837

Additional advancements took place in1797 when André-Jacques Garnerin designed and tested a parachute capable of slowing an aeronaut’s descent. His first substantial parachute jump was from a height of over 3,000 feet from a hydrogen balloon above Paris.

The great problem is at length solved. The air, as well as the earth and the ocean, has been subdued by science, and will become a common and convenient highway for mankind. The Atlantic has been actually crossed in a balloon…

–Edgar Allan Poe, “The Balloon Hoax”

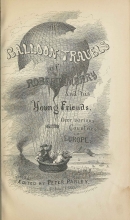

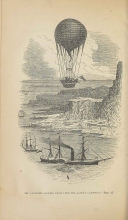

Poe’s mischievous balloon hoax was not the usual way ballooning was depicted in the press and literature. Under the name Peter Parley, Samuel Goodrich wrote popular stories of ballooning for children. Goodrich’s tales combined adventure and science as a way to educate and entertain young readers. Literature was one of the popular ways in which readers learned about new scientific fields like meteorology.

39088006479059_0011.jpg

39088006479059_0008.jpg

39088006479059_0009.jpg

39088006479059_0036.jpg

39088006479059_0330.jpg

The Balloon Travels of Robert Merry and His Young Friends over Various Countries in Europe

New York, 1863

Aneroid barometer

ca. 1870–1900 National Museum of American History (Photo: Hugh Talman) |

Ballooning provided an opportunity to study meteorological phenomena. Portable weather instruments, like this barometer, were used in balloon ascents to measure atmospheric pressure and record height, temperature, and humidity.

In 1862, the British Association for the Advancement of Science appointed meteorologist James Glaisher to study the atmosphere by balloon, and his work is documented in volumes such as 1871's Travels in the Air. During one flight, Glaisher and his co-pilot Henry Coxwell ascended a record 36,000 feet. The air was so thin and cold that their test-subject—a pigeon—froze, while Glaisher passed out. Coxwell had to climb into the rigging to release a valve line and stop the ascent.

As the 19th century progressed, fantastic airships became a mainstay of fiction. Intrepid travelers flew beyond the gravitational pull of the Earth to Mars. Ships sailed from the ocean into the air.

Creative minds were inspired by the possibilities that flight held and pictured a far-flung future with many of their works now revered as early examples of science fiction. In the late 1800s, novelist and illustrator Albert Robida drew images of France in the 1950s, when flying machines filled the skies.

![In the skies above Paris, Illustration from Albert Robida, [The twentieth century] Paris, 1880s](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/39088008658270_0117_crop.jpg) Albert Robida

Le vingtième siècle [The twentieth century] Paris, 1880s |

![Illustration from Albert Robida, Le vingtième siècle: la vie électrique [The twentieth century: the electric life] Paris, 1893](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/g2-7_39088009414715_001_crop.jpg) Albert Robida

Le vingtième siècle: la vie électrique [The twentieth century: the electric life] Paris, 1893 |

In his 1909 story With the Night Mail, Rudyard Kipling describes life in the year 2000, featuring airships powered by a device called Fleury’s Ray. Flight is so commonplace in Kipling's fictional future that families place ads for personal pilots.

39088016478091_0001.jpg

2_kipling_39088016478091_0011.jpg

stitched_kipling_39088016478091_0002.jpg

39088016478091_0008_crop.jpg

39088016478091_0133_crop.jpg

With the Night Mail, a Story of 2000 A.D.

New York, 1909

Frank Reade was an extremely popular series of dime novels, starring Reade as a brilliant inventor. Reade traveled the world in fantastic flying machines searching for treasure. His wild adventures captured public attention when practical flight seemed possible and imminent.

One of the few women working in the genre at the time, Sara Weiss wrote in 1903 of an airship capable of flying to Mars so scientists could study the plants, animals, and other life thought to exist on the Red Planet.

There isn’t a big power in Europe, or Asia, or America, or Africa, that hasn’t got at least one or two flying machines hidden up its sleeve at the present time. Not one. Real, workable, flying machines. And the spying! The spying and manoeuvring to find out what the others have got.

—H.G. Wells, The War in the Air

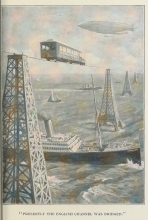

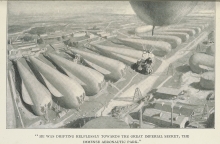

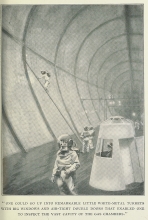

Meanwhile, H.G. Wells crafted stories that questioned where the future would take us. Lighter-than-air ships, or dirigibles, were the first engine-powered aerial ships. Wells pictured a time when such ships would become machines of war. Today his dark vision seems almost prophetic— the U.S. and Germany employed dirigibles for aerial combat during World War I.

2_wells_39088008979957_0001.jpg

2_wells_39088008979957_0009.jpg

2_wells_39088008979957_0008_crop.jpg

39088008979957_0029_crop.jpg

39088008979957_0115_crop.jpg

39088008979957_0165_crop.jpg

The War in the Air

London, 1908

Winged Flight

Harry Kennedy

The Flying Man, or the Adventures of a Young Inventor New York, 1891 |

While tales of ballooning and fanciful flying machines fascinated the public, the reality of mechanized winged flight failed to take off. Many believed that motorized flying machines could exist only in fiction.

Gravity could not hold down the future of flight as tinkerer and scientist alike aimed for the sky. Important breakthroughs were made in the mechanics of flight by studying birds, though many failed attempts were made off hills and cliffs, by inventors using mechanical wings strapped to their backs.

The dream of self-powered flight features in a novel by Robert Paltock that was released the same year the Montgolfier brothers launched their first balloon flights. The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins, a Cornish Man tells of a traveler who is shipwrecked at the South Pole. He discovers a cave that leads to a subterranean world inhabited by Glums and Gawrys, beings who fly using mechanical wings.

39088011700341_0007.jpg

39088011700341_0064_crop.jpg

39088011700341_0087_crop.jpg

39088011700341_0114_crop.jpg

39088011700341_0165_crop.jpg

The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins, a Cornish Man:

Taken from His Own Mouth

London, 1783

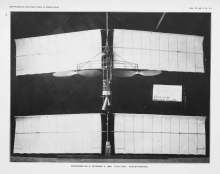

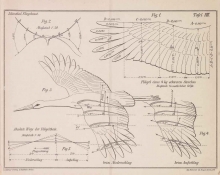

Early aviators were able to enjoy a taste of personalized flight using gliders, and these devices set the stage for powered flight. Otto Lilienthal designed and tested the most successful gliders of the time, using designs inspired by his studies of the anatomical structure of bird wings. Lilienthal's work helped persuade the scientific community and the public that powered flight could one day be practical—even though he died in 1896 due to injuries sustained in a glider crash.

2_g2-6_lilienthal.jpg

vogelflugalsgru00lili_0001.jpg

vogelflugalsgru00lili_0007.jpg

vogelflugalsgru00lili_0006_crop.jpg

vogelflugalsgru00lili_0057_crop.jpg

vogelflugalsgru00lili_0233_crop.jpg

Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst

[Bird flight as the basis of the art of flying]

Berlin, 1889

Gift of the Burndy Library

![Jules Verne, Robur-le-conquérant [Robur the Conqueror] Paris, 1886](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/sil28-091-01.jpg)

![Jules Verne, Robur-le-conquérant [Robur the Conqueror] Paris, 1886](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/sil28-091-02_crop.jpg)