Infinite Worlds

Exploring the Universe and Seeking Extraterrestrial Life

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen... illustrated by Gustave Doré London, 1867 |

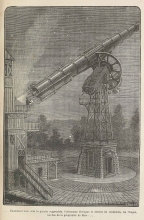

Astronomers in the 1800s were mapping the sky and exploring the known boundaries of the universe, assisted by advances in telescopes and the invention of photography. The outermost planets of the solar system were found, and new star clusters were viewed. These discoveries reignited an age-old question: Could life exist on other worlds? The question of extraterrestrial life, at the time known as the “plurality of worlds” theory, was a hot topic of debate, and the emerging genre of science fiction took it even further, harnessing scientific thought to envision travel to Earth-like planets.

In many literary works of the era, imaginary voyages mixed fact and fantasy in surprising ways. Based on the tall tales of a real historical figure, the exploits of fictional Baron Munchausen allowed the reader to travel on a bridge from England to Africa, fly on a cannonball and sail on a ship to the moon.

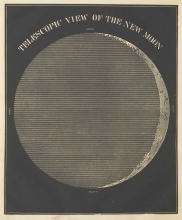

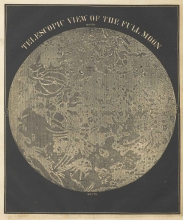

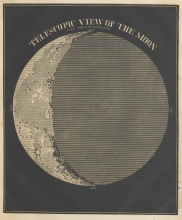

If we be ever to obtain an ocular demonstration of the habitability of any the celestial orbs, the Moon is the only one, where we can expect to trace, by our telescopes, indications of … intelligent beings.

– Rev. Thomas Dick, The Christian Philosopher, 1823

![Leonid meteor shower over Niagara Falls, Edmund Weiss, Bilder-Atlas der Sternenwelt [Image atlas of the star world] Stuttgart, 1892, Courtesy U.S. Naval Observatory Library](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/loan_3_leonid_meteor_storm.jpg)

Leonid meteor shower over Niagara Falls

Edmund Weiss Bilder-Atlas der Sternenwelt [Image atlas of the star world] Stuttgart, 1892 Courtesy U.S. Naval Observatory Library |

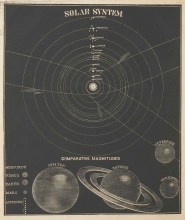

Towards the end of the 18th century, British astronomer William Herschel made significant advancements in astronomy through his cataloging of stars and nebulae along with his discovery of Uranus in 1781, which renewed interest in the study of our solar system.

New discoveries generated public interest in astronomy as a subject of study and as a leisure activity, creating an ever-growing class of amateur astronomers. Expeditions to observe astronomical phenomena, such as eclipses and comets, drew amateurs and professionals alike.

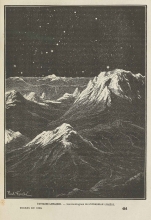

The Great Leonid Meteor Shower of 1833 awakened interest in astronomy in the U.S. Primarily visible east of the Rockies in North America, the meteor shower was splashed all over the newspapers. The fiery display also ignited a new area of astronomy: determining the nature of meteors. While such events brought increased observation and study of astronomy, wild speculation still abounded as to the true nature of meteor showers, comets, and the like. Were they simply astronomical events or omens of bad things to come?

…it seems like acquiring a fearful supernatural power when any remote mysterious works of the Creator yield tribute to our curiosity. It seems almost a presumptuous usurpation of powers denied us by the divine will, when man…steps forth, far beyond the apparently natural boundary…and demands the secrets and familiar fellowship of other worlds.

–Richard Adams Locke, “Great Astronomical Discoveries," The Sun, 1835

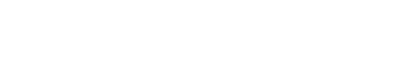

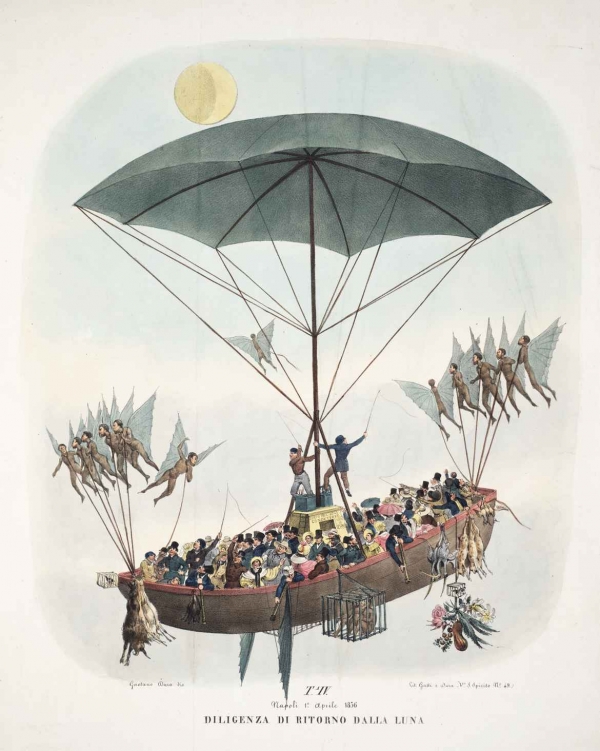

The depiction of the Moon Hoax by Leopoldo Galluzzo is a mash-up of the original news articles, Poe’s moon hoax, and various retellings of the story in other newspapers of the time. It is likely that the inclusion of the balloon powered flying machine is from Poe’s moon hoax in which Hans Pfaall travels to the moon by balloon. The passengers on the flying machine are likely missionaries and scientists sent to study the man-bats and teach them about the bible. After the Sun story appeared, a proposal appeared in other New York City papers to send a ship to the moon to bring the lunarians bibles as well as to study them.

Altre scoverte fatte nella luna dal Sigr. Herschel

[Other lunar discoveries from Signor Herschel]

Naples, 1836

![Frédéric de Courcy and Charles Plantade, Ma lune: Parodie de Ma Normandie [My moon: Parody of My Normandy] Paris, 1836](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/media/exhibitions/malune00deco_0001_crop.jpg)

Frédéric de Courcy and Charles Plantade |

The enduring popularity of the Moon Hoax, which inspired songs and stage plays, was due not only to the fantastic nature of the story but also to the popularity of all things astronomical.

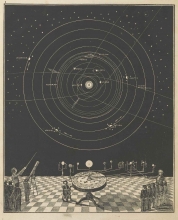

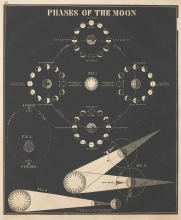

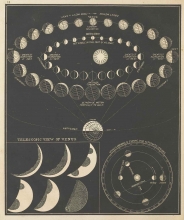

In response to the public’s growing interest in astronomy, educator Asa Smith was inspired to teach the subject in schools. His illustrated textbook helped introduce the public to what the perceivable universe looked like. During this time, direct observation and illustration provided the visual information of what the observable heavens looked like.

The invention and development of photography, from the first photographic image by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1827 to its rise in popularity during the 1850s, led to the serious use of photography for research within astronomy by the 1890s.

39088006065619_0005.jpg

39088006065619_0004.jpg

39088006065619_0008_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0030_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0032_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0034_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0035_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0049_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0010_crop.jpg

39088006065619_0018_crop.jpg

Smith's Illustrated Astronomy: Designed for the Use of the Public or Common Schools in the United States

New York, 1849

Gift of the Burndy Library

Detail from broadside for Charles Came lecture, about 1850

National Museum of American History |

Outside of the schoolroom, traveling science lectures, like the ones put on by Charles Came in upstate New York, helped spread scientific discoveries and knowledge to the general public. Lecturers used mechanically animated visuals, such as magic lantern slides, and enthralling experiments to present scientific thought as something wondrous, entertaining and even terrific in nature.

Magic lantern shows were extremely popular forms of entertainment and education and many shows featured astronomy themes. The slides used hand-painted images, lithographic decals, or photographs on glass to show the moon, eclipses and comets, helping to bring the heavens down to Earth. Mechanical slides provided early animation of celestial events.

National Museum of American History

(Photo: Hugh Talman)

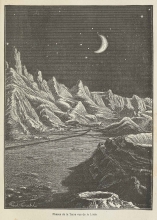

In France, Camille Flammarion was a well-known astronomer, writer and popularizer of science. His work of speculative science, Les terres du ciel, or "Lands of the Sky", featured illustrations from the perspective of a moon dweller. His books helped perpetuate the “plurality of worlds” theory through the end of the 19th century.

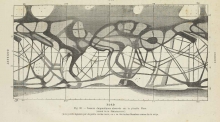

Another contentious but popular theory of the late 19th century was that canals existed on Mars, with some believing that the canals were made by intelligent alien life. In "Lands of the Sky", Flammarion poses this idea along with imagined depictions of life on other planets, including Venus. While it turns out that the canals of Mars were optical illusions, there is mounting scientific evidence that at one time there might have been water on Mars.

39088015922164_0503_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0543_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0555_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0559_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0466_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0009_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0073_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0017_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0181_crop.jpg

39088015922164_0329_crop.jpg

Les terres du ciel; voyage astronomique sur les autres mondes...

[Lands of the sky: astronomical travel to other worlds]

Paris, 1884

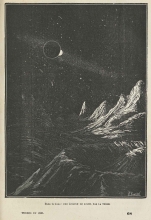

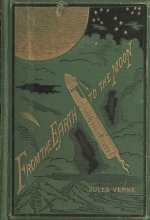

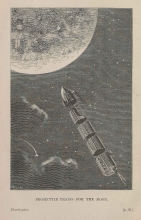

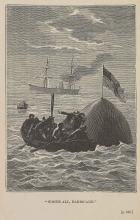

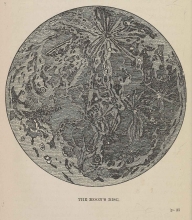

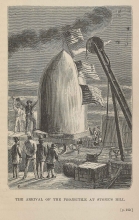

But perhaps the era's most famous example of popularizing science is From the Earth to the Moon, penned by French novelist Jules Verne in 1865. Verne’s story relies on both the science and fiction of the time. A main character makes references to Poe’s “Hans Pfaall” tale and Locke’s Moon Hoax, as well as to contemporary science. Verne imagined employing artillery technology from the Civil War to launch a ship to the moon. His vision of a rocket launched from Florida foreshadows NASA launches from Cape Canaveral.

Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon was the inspiration behind Georges Méliès most famous short film Voyage Dans La Lune [A Trip to the Moon] from 1902.

3_verne_39088002245697_0001.jpg

3_verne_39088002245697_0448_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0010_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0393_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0490_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0052_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0077_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0201_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0426_crop.jpg

39088002245697_0464_crop.jpg

From the Earth to the Moon Direct in Ninety-seven Hours and Twenty Minutes, and a Trip Round It

New York, 1874

About 1835 a small treatise…related how Sir John Herschel…had by means of a telescope brought to perfection by internal lighting, reduced the apparent distance of the moon to eighty yards! He then distinctly perceived caverns…sheep with horns of ivory, a white species of deer and inhabitants with membranous wings, like bats. This brochure, the work of an American named Locke…

–Jules Verne, From the Earth to the Moon, 1874