Feed aggregator

Snacking While Out and About a Century Ago

What do you do when you are out and about and have a craving for a quick snack? Shoppers, picnickers, theatregoers, or someone simply out for a stroll in the early 20th Century might have stumbled across a popcorn and peanut machine like one shown in this trade catalog.

The trade catalog is by C. Cretors & Co. and is both untitled and undated. However, we believe it was published circa 1924 by piecing together some information from the catalog, such as the company was established in 1885, it mentions 40 years of experience in building these machines, and it has a library stamp date of 1924 on the front pages.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), front cover.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), front cover.

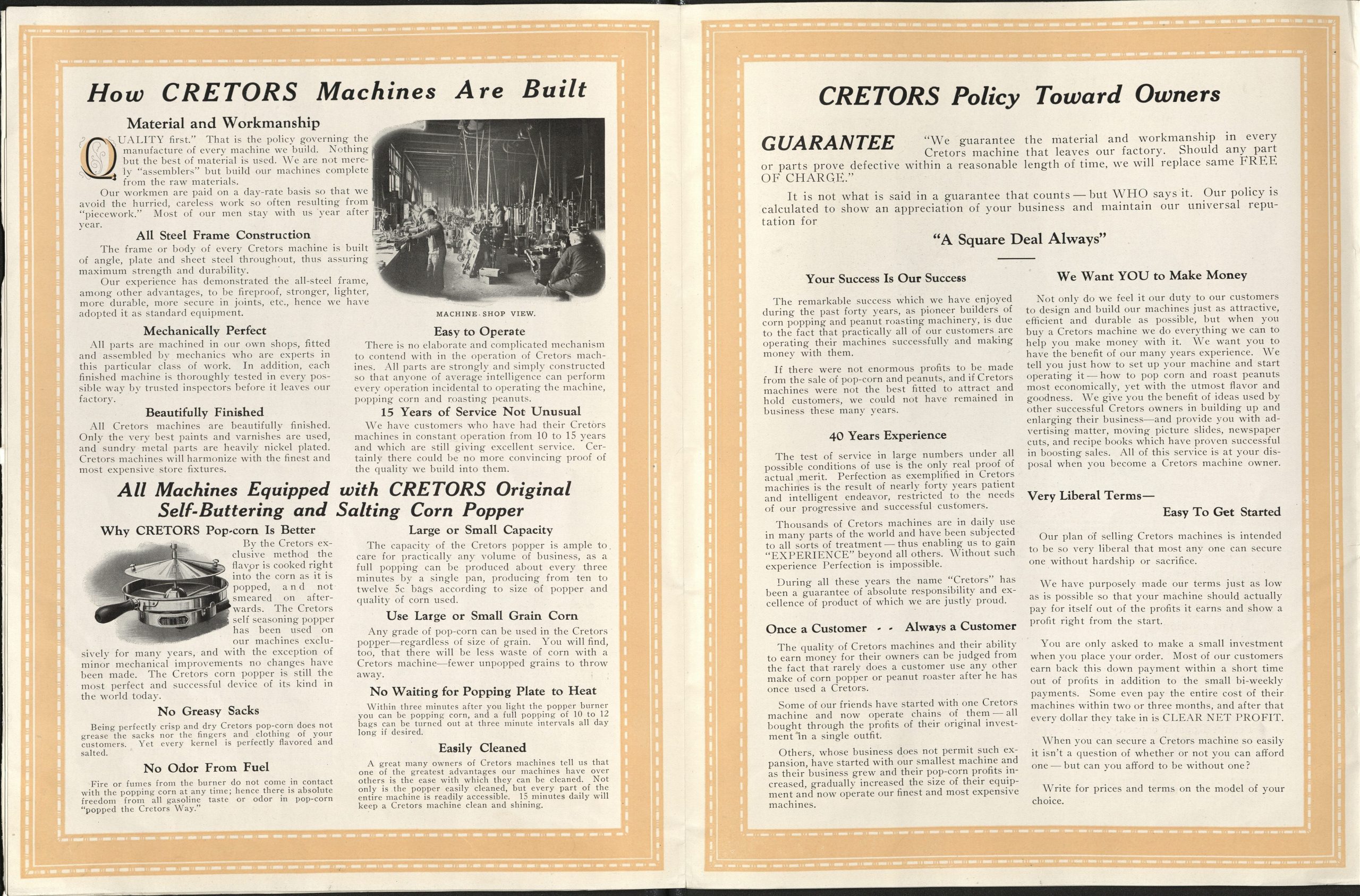

These popcorn and peanut machines were suitable for both indoor and outdoor use. Some ideas for locations included theatres, department stores, ballgames, fairs, parks, picnic areas, and even sidewalks. The machines were constructed of all-steel frames and finished with paint and varnish. The various metal parts were nickel-plated. After completion, each machine was tested by inspectors.

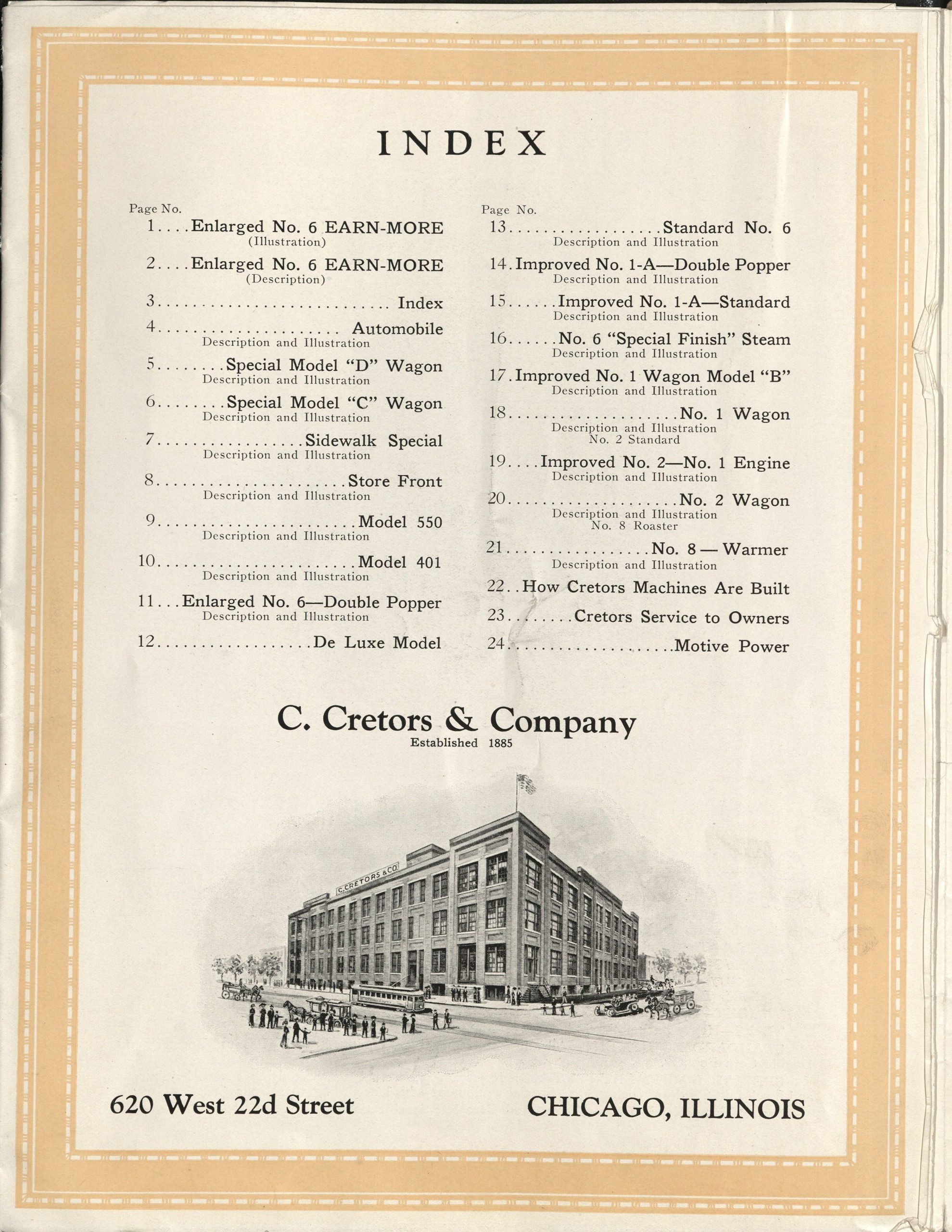

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 3, Index and C. Cretors & Co. building.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 3, Index and C. Cretors & Co. building.

The popcorn machines included a self-seasoning popper. This meant the flavor was “cooked right into the corn” during the popping process rather than being “smeared on afterwards.” This also saved time as additional buttering or salting was not necessary.

The machine was ready to begin popping within three minutes after the burner was lit. And then approximately every three minutes after that, it could pop 10-12 bags. The popcorn never encountered the burner’s fire or fumes which prevented it from having the taste or smell of gasoline.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), pages 22-23, general information about machines including images of a popcorn popper and machine shop where machines were built.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), pages 22-23, general information about machines including images of a popcorn popper and machine shop where machines were built.

According to this catalog, the parts of the machine were easy to access which helped with cleaning. It recommends spending just “15 minutes daily” to keep it clean.

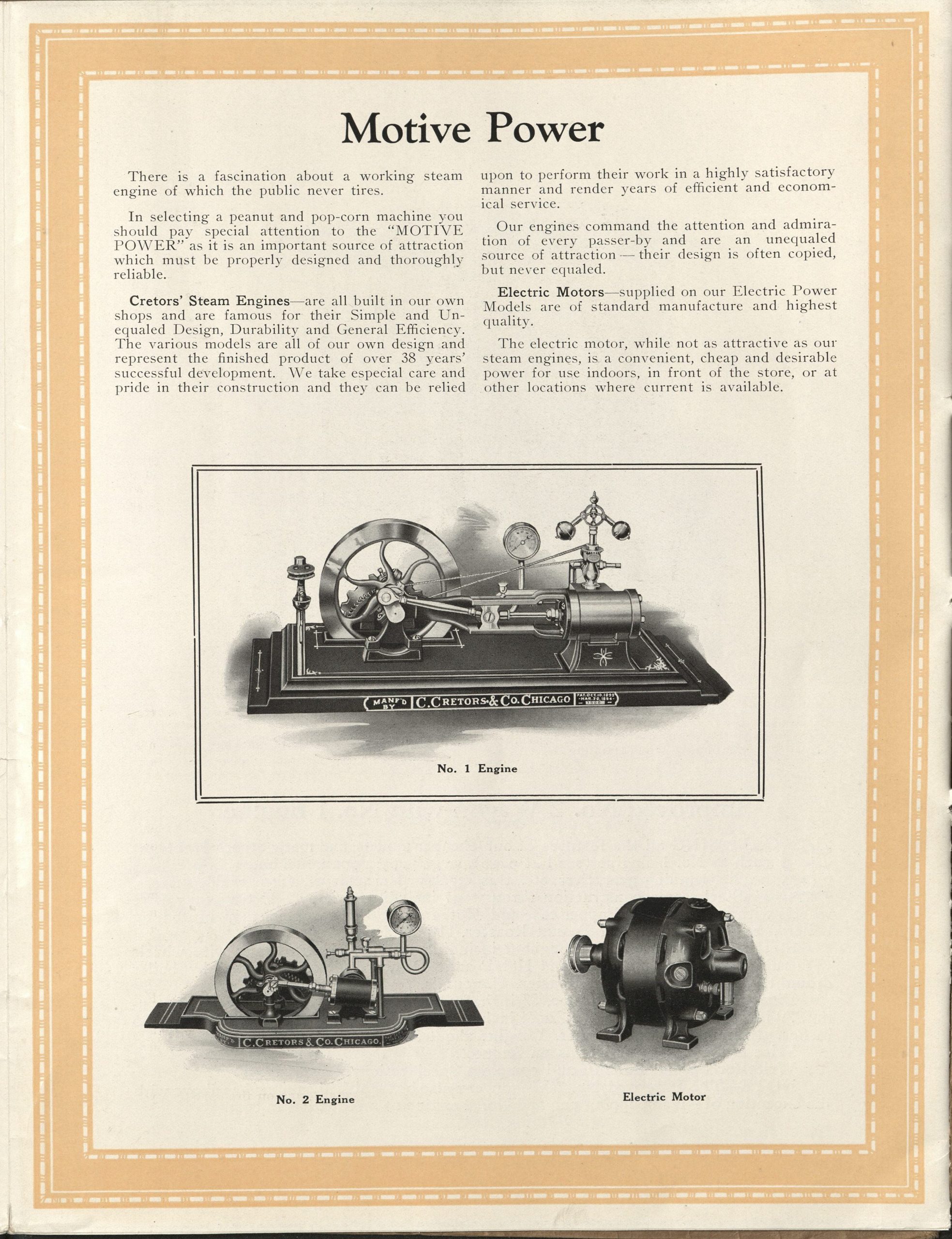

One full page of this catalog is devoted to information about steam engines and electric motors used in these machines. As the catalog points out, the electric motor (below, bottom right) might not be as beautiful as the steam engine, but it was a good option when a machine was positioned indoors or in front of a store. That is, if a nearby and ready supply of electrical current was available.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 24, steam engines and electric motors for the popcorn and peanut machines.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 24, steam engines and electric motors for the popcorn and peanut machines.

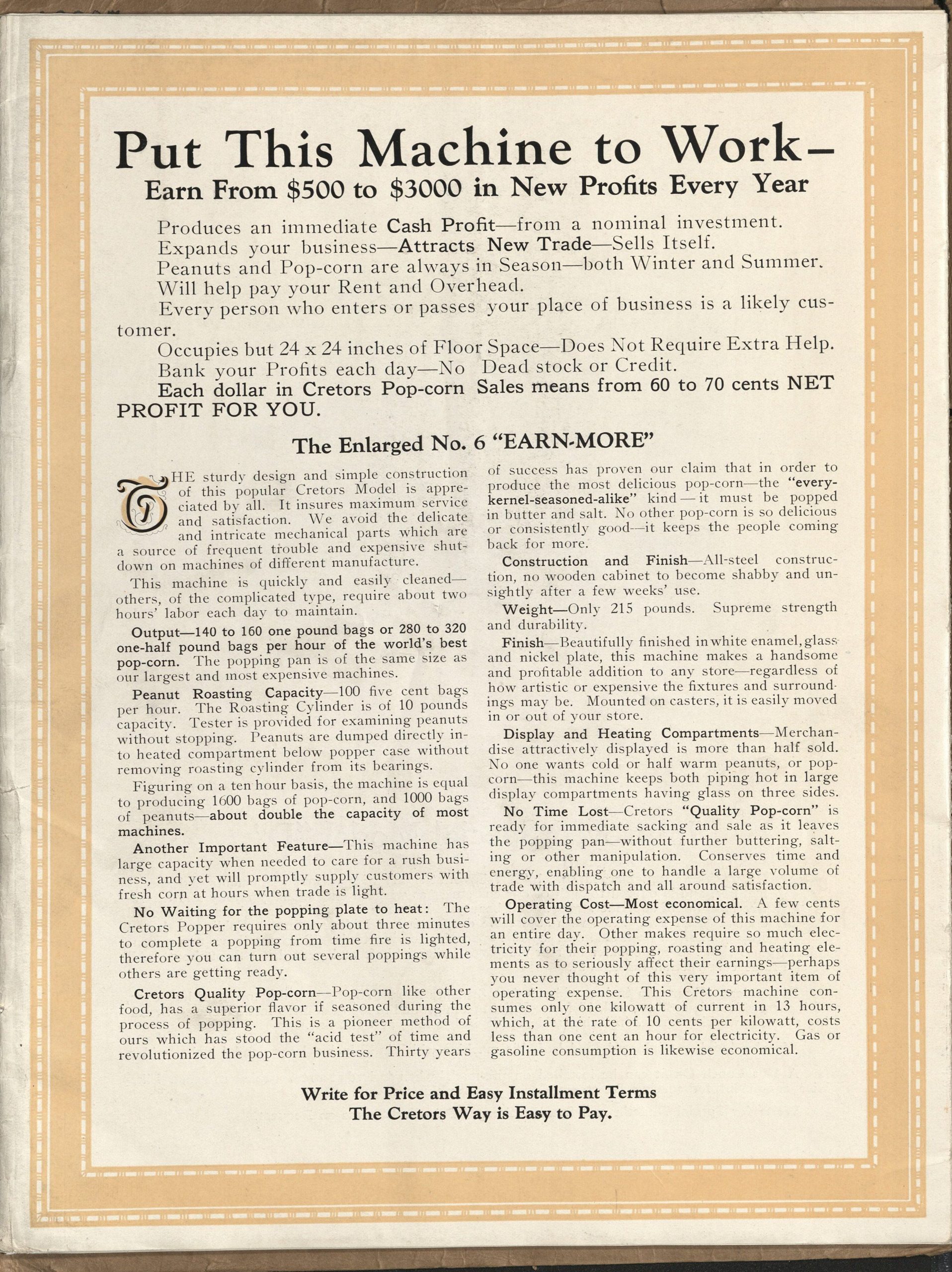

The Enlarged No. 6 “Earn-More” Machine is featured on the first page of this catalog (below). Though it was a stand-alone machine and not incorporated into a wagon or automobile, it was equipped with casters to make it mobile. With a name such as “Earn-More,” it might have attracted attention of store owners and vendors desiring a large capacity machine to increase their sales. According to this catalog, the “Earn-More” Machine could pop 140-160 one-pound bags of popcorn per hour. And when it came to half-pound bags, it popped 280-320 bags per hour.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 1, Enlarged No. 6 Special Finish “Earn-More” Machine for popping corn and roasting peanuts.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 1, Enlarged No. 6 Special Finish “Earn-More” Machine for popping corn and roasting peanuts.

The “Earn-More” was also a peanut machine. Each hour, it had the ability to produce 100 five-cent bags of roasted peanuts. It came with a tester to ensure the peanuts were properly roasted. The machine’s three glass sides provided a visual of the warm buttered popcorn and roasted peanuts available for sale. Besides catching the attention of passers-by, the glass sides also allowed customers to see the machine in action.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 2, description of Enlarged No. 6 “Earn-More” Machine for popping corn and roasting peanuts.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 2, description of Enlarged No. 6 “Earn-More” Machine for popping corn and roasting peanuts.

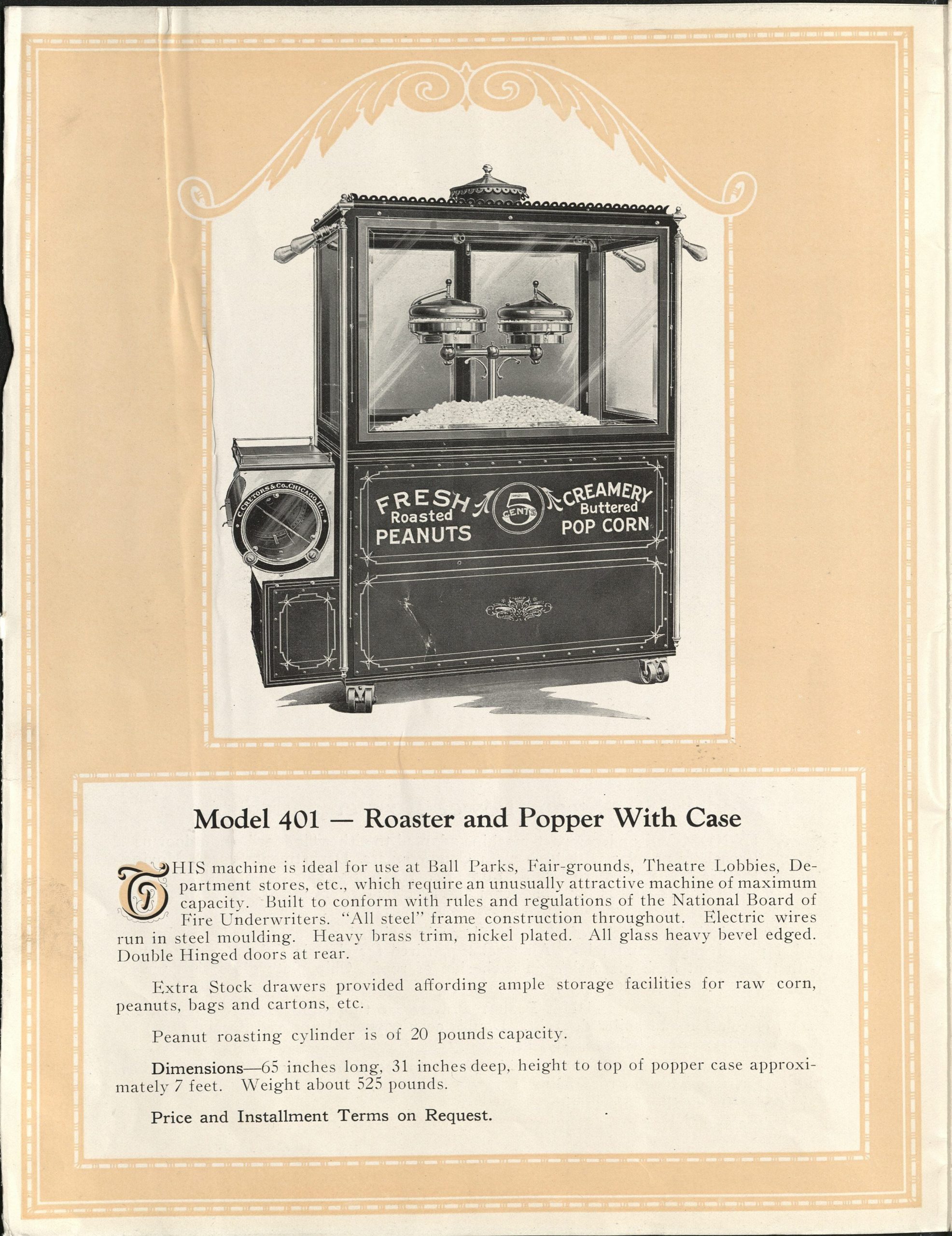

Just like many of the machines in this catalog, the Model 401 Roaster and Popper with Case, shown below, was both a popcorn and peanut machine. Described as “an unusually attractive machine of maximum capacity,” it might have been used at venues for special events. The catalog suggests ballparks, fairgrounds, theatre lobbies, or department stores. The Model 401 included drawers for storing extra supplies, like raw corn, peanuts, bags, and cartons. Due to its ability to supply popcorn and peanuts at “maximum capacity” and a peanut roasting cylinder of 20-pounds capacity, this extra space probably came in handy.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 10, Model 401 Roaster and Popper with Case.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 10, Model 401 Roaster and Popper with Case.

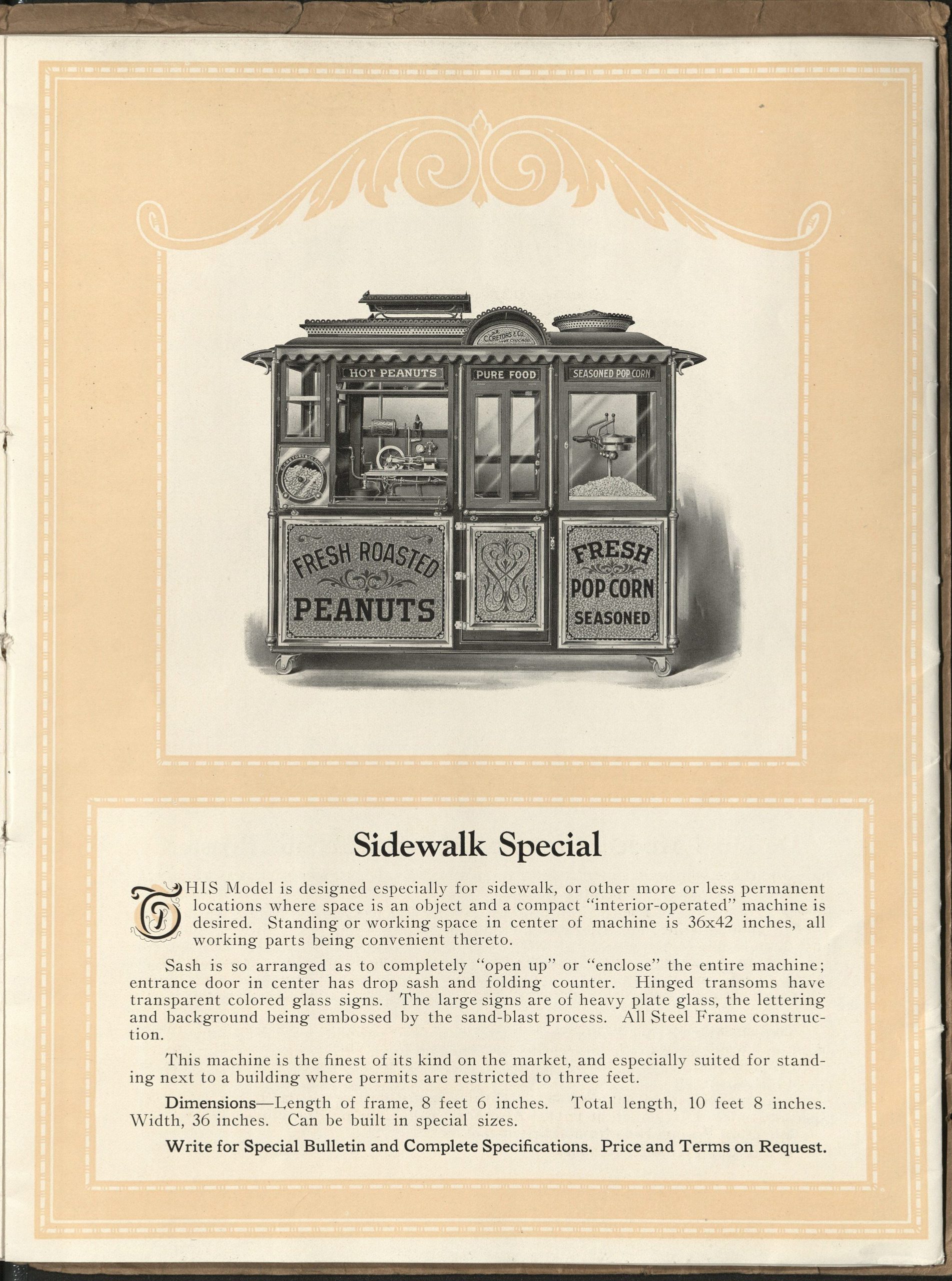

The Sidewalk Special (below) was another popcorn and peanut machine. As the name suggests, it might have been situated on a sidewalk or street corner, but it was also suitable for other confined and not so mobile locations. It measured 10 feet 8 inches long and three feet wide. The operator entered the “Sidewalk Special” via a central door and worked in a very small space measuring 36 x 42 inches. The door featured a drop sash and folding counter which allowed interaction with customers.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 7, Sidewalk Special popcorn and peanut machine.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 7, Sidewalk Special popcorn and peanut machine.

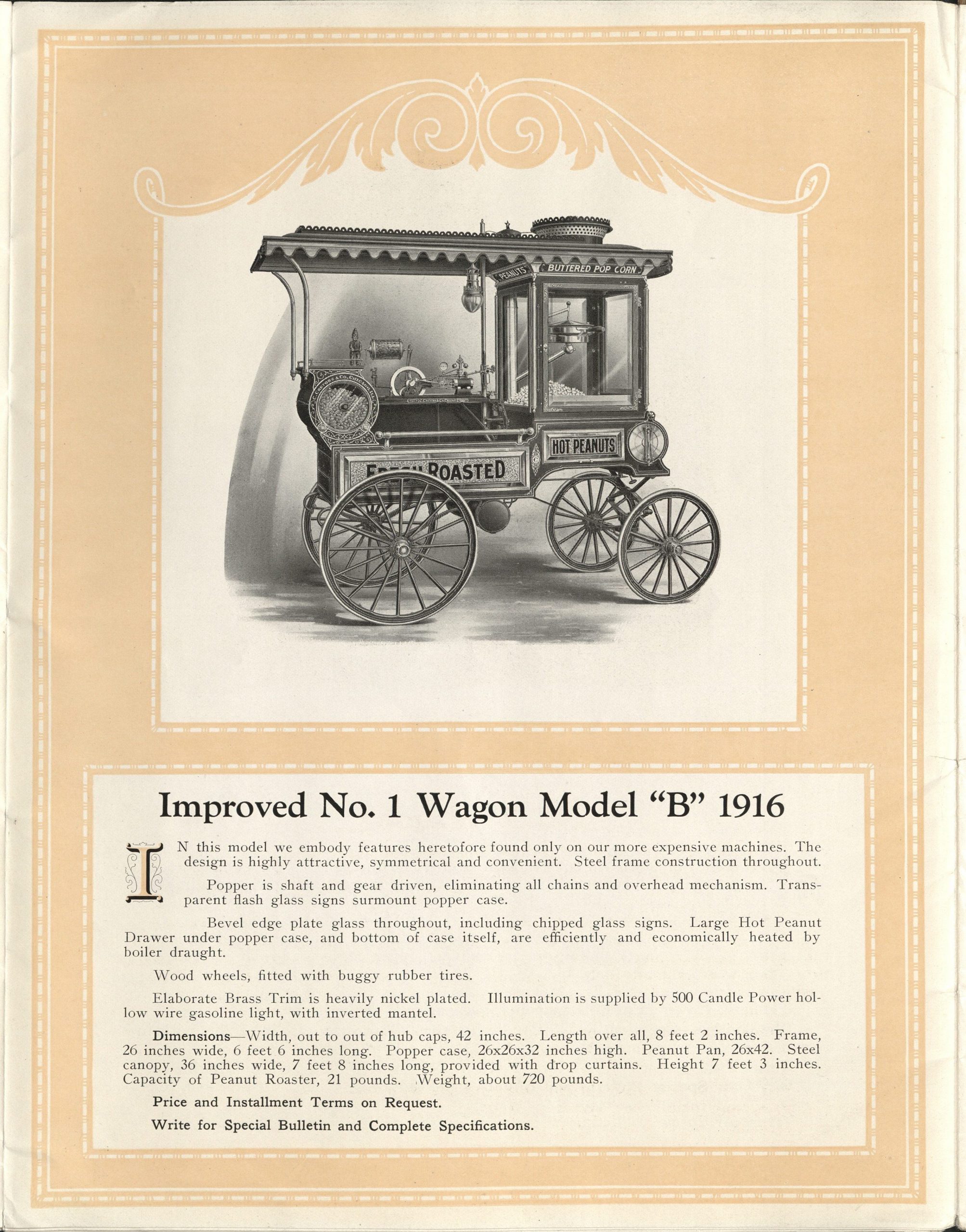

Some machines were incorporated into a wagon, such as the Improved No. 1 Wagon Model “B” 1916, illustrated below. Described as “attractive, symmetrical and convenient” in design, it featured a steel canopy with drop curtains, brass trim, heated peanut drawers, and a 21-pound peanut roaster capacity. Signs reading “Fresh Roasted,” “Hot Peanuts,” and “Buttered Pop Corn” were located on the sides of the wagon to attract customers. The 8-foot 2-inch wagon was equipped with wood wheels and buggy rubber tires.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 17, Improved No. 1 Wagon Model “B” 1916.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 17, Improved No. 1 Wagon Model “B” 1916.

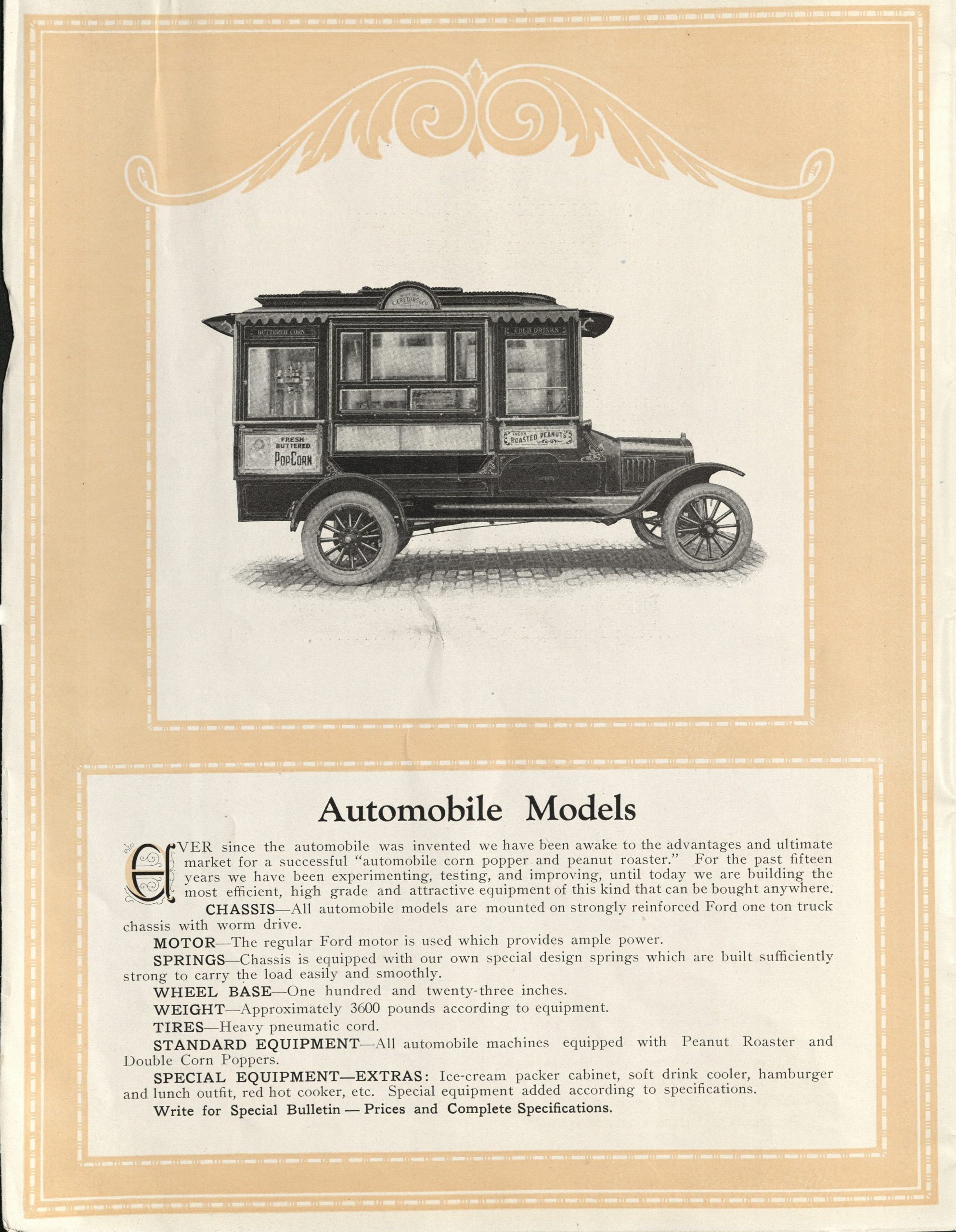

Some vendors who desired to be more mobile in their business might have considered the “Automobile Models.” Besides standard equipment like the peanut roaster and double corn popper, these vehicles could also be fitted with other food equipment. Options included ice cream packer cabinets, soft drink coolers, equipment for hamburgers and lunch items, and cookers. For example, the automobile illustrated below advertised cold drinks on its signs along with popcorn and peanuts.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 4, Automobile Model with corn popper, peanut roaster, and cold drinks.

C. Cretors & Co., Chicago, IL. Untitled C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog (undated), page 4, Automobile Model with corn popper, peanut roaster, and cold drinks.

As might be expected, installation and user instructions were included with each machine. But that was not all. The company also provided new owners with promotional items, including advertising materials, moving picture slides, newspaper cuts, and recipe books. The suggestions in these materials came from other owners sharing ideas that had worked for them.

This untitled and undated C. Cretors & Co. trade catalog and other trade literature by C. Cretors & Co. are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Curiosity Preserved the (AV) Memories

“When did I get my first TV? When I was eight?”

*Mom laughs* “More like when you were one…”

Screenshot of Kayla Henry-Griffin as child from a collection of family Hi8 tapes.

Screenshot of Kayla Henry-Griffin as child from a collection of family Hi8 tapes.

Family and technology have always been in the picture for me. They are intertwined, connected, and that bond can never be broken. I have always been interested in how technology works and how I could use it not only in my artistic practice, but also how I can save family memories. I look towards pictures of my grandmother whom I never met to understand my family and how we are dispersed globally. I look towards camcorder-recorded home movies of me to understand my role and my place in the Henry/Griffin/Toney family. I picked up skills from the Mac computer in my childhood home, I learned about pop culture through the TV with the wooden cabinet in the living room, and I picked up my love of video games when I bought my first game at the age of eight (it was Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life for the console GameCube).

Screenshot of gameplay in Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life (Gamecube English version).

Screenshot of gameplay in Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life (Gamecube English version).

All of this to say- I have been immersed in audio-visual technology to the point that I wanted to preserve the memories behind it. All forms of technology are a vessel for me to get closer to how I memorize math equations to even how I recollect that major move I did from California to Mississippi. Of course, this took a while for me to truly understand that this was a personal and professional path I wanted to take on. At my alma mater, I created my own major to encompass my love for photography and optics (my degree literally says ‘Photography and Optics’). I learned about art conservation during this time and since then, I have been on this professional journey of preserving cultural heritage.

In 2018, I attended a Software Preservation Network (SPN) workshop in Texas that focused on emulation and preservation. I met a multitude of folks in the cultural heritage field that worked with non-traditional materials from VHS tapes to computer software like Microsoft Golf. After talking with someone who works for Strong Museum of Play, I was more than elated to hear that I could preserve video games if I wanted to. That moment, in combination with all of my heartfelt experiences with technology, led me to pursue this dream of preserving memories from non-traditional mediums.

During the pandemic, I attended the Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) program at New York University. During that time, I interned at various organizations (Los Herederos, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Third World Newsreel, and The Museum of the Moving Image) that shaped my philosophy on preserving cultural heritage. Even though I mostly worked with magnetic media in the internships, I also had experience with software-based art and film. I found a love for mysterious and obscure formats like the HIPAC, and soon learned that my love of video games meant that I also would love to preserve them and the experiences that people have with video games.

Following my graduation from the MIAP program, I took on a fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where I continuously worked with conservation of time-based media with mentor and supervisor Jonathan Farbowitz. One task I was focused on during the fellowship was to finish a project from my internship with a Philippe Parreno artwork by the name of, With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (Purple, Rule #3). This was a project that challenged my philosophy and practice of preserving audiovisual media and time-based media. The project further pushed me to critically think about the ethics of preservation and showed me that all media will not be treated or preserved the same.

Philippe Parreno. Pilar Corrias Installation view of With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (Green, Rule#1), 2014.

Philippe Parreno. Pilar Corrias Installation view of With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (Green, Rule#1), 2014.

My experiences have been mainly with museums and small non-profits and those experiences have shown me that in fact, no matter how small or large the institution is, saving cultural heritage means preserving memories. My role at the Audio Visual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI) has been to assess, catalog, and conduct conservation work of collections throughout the Smithsonian. Knowing that I am a part of the work that is occurring to preserve media collections has personally made me more sensitive to how we care for others and their experiences. My time at Smithsonian has just started this summer and I have seen the progress and impact AVMPI has made to care for the cultural heritage on media. My role as a professional in this field is similar to my role as a Henry-Griffin family member- preserve memories and stories for years to come.

Lost in the Vertical Files

My name’s Dawson, and over the summer I worked as an intern at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library in DC. I’m currently an Art History and Visual Culture student at Bard College. I applied to the internship last spring with only a little archival experience under my belt, and no idea of how I would live in DC if I even got the position. It was a total leap of faith, and I’m still a little surprised I landed on two feet. In the cover letter, I expressed my belief that “[w]orking with the library’s art and artist files is an opportunity for me to engage directly with the histories of modern American art, and the role of the nation’s emblematic contemporary museum in showing and shaping said histories.” At the time, I had no idea if that would really hold weight or not, but it ended up being more true than I could have expected.

Here was what the job was like, day-to-day, in short. The Hirshhorn has, since its inception, collected various ephemera connected to artists whose work the Hirshhorn was interested in obtaining or ultimately did obtain in its collection. Some of the ephemera even dates to before the museum, when Joseph Hirshhorn had the collection and not yet the institution to hold it. All this ephemera is now stored in the library’s vertical files, one file for each artist. Ephemera is media that is not intended to be preserved long-term – in our collection there are postcards from various artists’ exhibitions, newspaper clippings of reviews, interviews, and obituaries, artists’ resumes and bibliographies, press releases, and lots and lots of advertisements for exhibitions. I would date all of these pieces of ephemera, stamp them with a small “HMSG” insignia, and then sort them chronologically. A lot of these glossy advertisements and obscure clippings aren’t really the kind of media that most libraries preserve, yet they do reflect important auxiliary and parallel histories to more straightforward sources– offering a history of art advertisement, histories of galleries and institutions, and how artists and their art are depicted and remembered on the most immediate levels.

Intern Dawson Escott in the Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library.

Intern Dawson Escott in the Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library.

This was my job description on paper, but because of some experience at school working with metadata I took the opportunity to spend a lot of time updating the online entries in the Smithsonian’s Art and Artist’s Files database and on Wikidata (if you’re curious, you can find me on there with the username PalmyranRealness) to better digitally represent the Artist Files’ contents and publicize the material available at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library for researchers. I feel strongly that most research in the present day is done online and in order for physical archives to remain used and helpful, there’s a definite need for them to have a digital presence. I updated birth and death dates, created files, clarified exactly which person each file represented (using a unique identification number called a VIAF), all kinds of minutia that make online research easier. In short, my time was spent half and half clarifying both the physical and digital presences of the Hirshhorn Library. So what, after two months, were the takeaways of a beginner’s first foray into library work?

The first takeaway was a practical change in perspective– I hadn’t ever conceptualized the absolute sprawl of artists there are in the world. The Hirshhorn Library really only catalogues information related to artists whose works are in the museum’s collection, and even with that constraint, there are still thousands of artists. In my two months there, working at a pretty consistent pace, I made it through two filing cabinet drawers. Llyn Foulkes to Julio Gonzalez– about a single letter of ground covered, all in all. My title of “A to Z Artist Files Intern” was definitely ambitious in hindsight. There were some well known names whose folders would take me the entire day to sort through– Helen Frankenthaler, Lucian Freud, Alberto Giacometti– and there were countless folders of unsung artists, which took me closer to fifteen minutes to work through. I would spend a long time falling into research rabbit holes, whether it be resolving conflicting birth dates or differentiating between several artists with the same name. (Sidebar– there were three John Ford painters I had to pick apart, and my Google search was severely complicated by the famous Western director. Total mess.) In my personal for-fun research at home, I would normally pick one or two artists, or a circle of artists, and read about them in-depth. But in working for a library, my scope of awareness by necessity widened to whole spheres of art which had never before caught my attention.

For example, I worked on our online entry for Ruth Cyril. I approached this artist as a name on a page and came away with an intimation of more than I can really grasp. I was trying to add birth and death years to the artist’s life, and in the process got lost in the murkiness of her name change and unsung biography. I caught just a glimpse of a wider world of the printmaking renaissance of Atelier 17 and the countless students at said school who went on to have long and varied careers. And then, just like that, I moved on to another name with its own situated culture and story. The world of art, really just the world, is full to the brim of unexamined artwork and unexamined lives and pure detail, pure intricacy. It’s a little overwhelming and humbling to come to a closer awareness of this fact we kind of accept at face level without necessarily having to deal with it. Even a small, neatly limited section of history is unthinkably large when approached with an eye for detail and its smallest, ephemeral pieces.

The second and bigger takeaway is that there is something oddly powerful to the whole process which is difficult for me to voice. I felt like a custodian to artists alive and dead. The word custodian has a janitorial connotation, and that was certainly part of the job. There was a lot of small manual labor that I refined each day to a personal art: rubber stamping, neat pencil handwriting, a tidy spreadsheet. But I felt too, that working on these countless artists in little ways was a small form of invocation, plucking a string somewhere in the vast interconnected web of history that is tying me to art history. Adding someone’s name to a database, their date of birth and death to Wikidata, was like a little resurrection. The organizational microadjustments I did in swaths were part of the culturally vital process of keeping an archive alive. That sounds overly cliche, but I really mean alive, in the sense that being a custodian to this archive made it visible, responsive to change, and part of a living community. It acted on me, and I it, and all that felt indescribably valuable and somehow essential to an historic process. I felt linked to the Hirshhorn’s librarians before me that I knew now by name, to curators and collectors, sculptors and painters, exhibitions long gone, artwork still here, somewhere. Linked, too, to the peers around me, the workers and researchers operating in this huge Smithsonian historical web that’s so large it’s a wonder to me it floats. But through this internship, polishing the organizational structures of all this ephemera, I got a sense of an undercurrent. Something pesky to describe that binds together impossibly wide times and spaces. I think libraries and museums are where you can come closest in contact to that undercurrent. If you’re tempted by this blog post at all, try and dip your toe in, and see if you don’t end up caught in the undertow like me.

Thanks for having me Hirshhorn and the whole Smithsonian Libraries and Archives system, especially to my supervisor Jacqueline Protka who made me feel truly welcome. If you’re curious about the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden Library, it’s open to the public by appointment and full of untapped knowledge.

Exploring Yellowstone in 1919

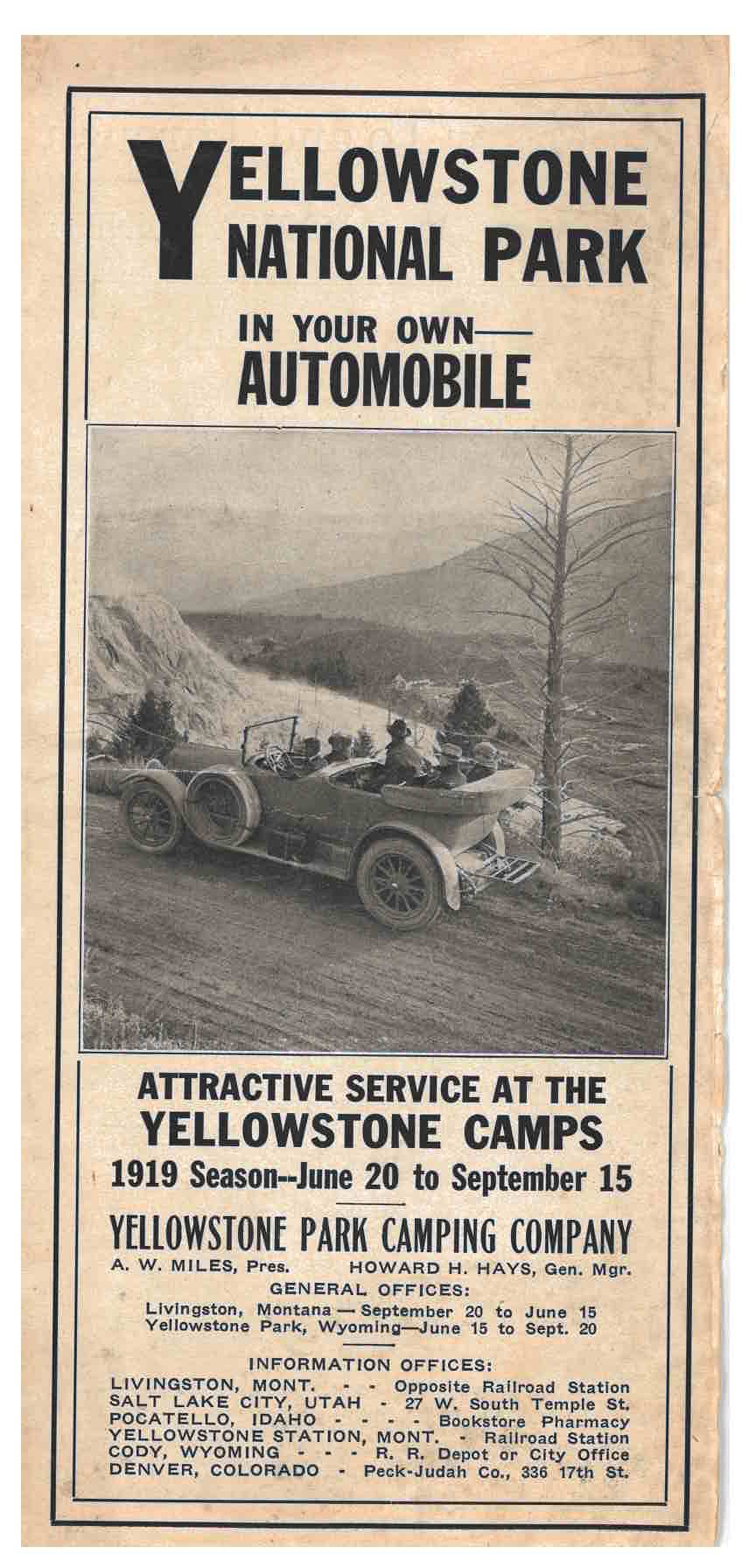

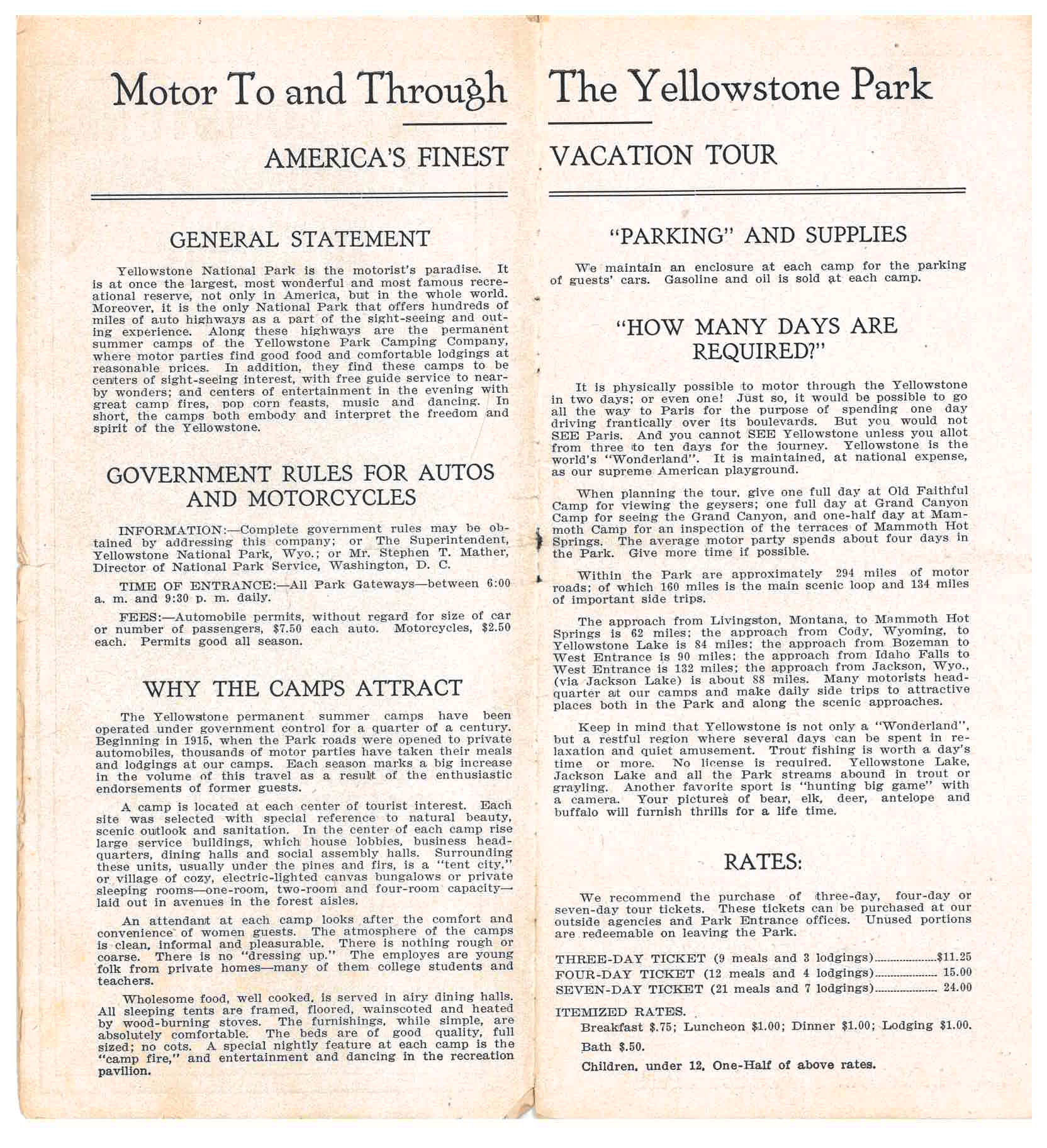

Camping, hiking, and enjoying the outdoors are common summer pastimes. This trade catalog from 1919 shows how visitors in the early 20th Century might have explored the wonders of Yellowstone National Park.

The trade catalog is titled Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919) by Yellowstone Park Camping Co. Referring to the national park as a “motorist’s paradise,” this brochure encourages tourists to visit in their own vehicle and camp, or lodge, at designated sites. The focus of the brochure is the summer season of 1919 which ran from June 20 to September 15.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), front cover/unnumbered page [1].According to this brochure, Yellowstone Park Camping Co. began providing accommodations for visitors beginning in 1915. However, it notes that these permanent summer camps located within Yellowstone National Park were “operated under government control.”

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), front cover/unnumbered page [1].According to this brochure, Yellowstone Park Camping Co. began providing accommodations for visitors beginning in 1915. However, it notes that these permanent summer camps located within Yellowstone National Park were “operated under government control.”

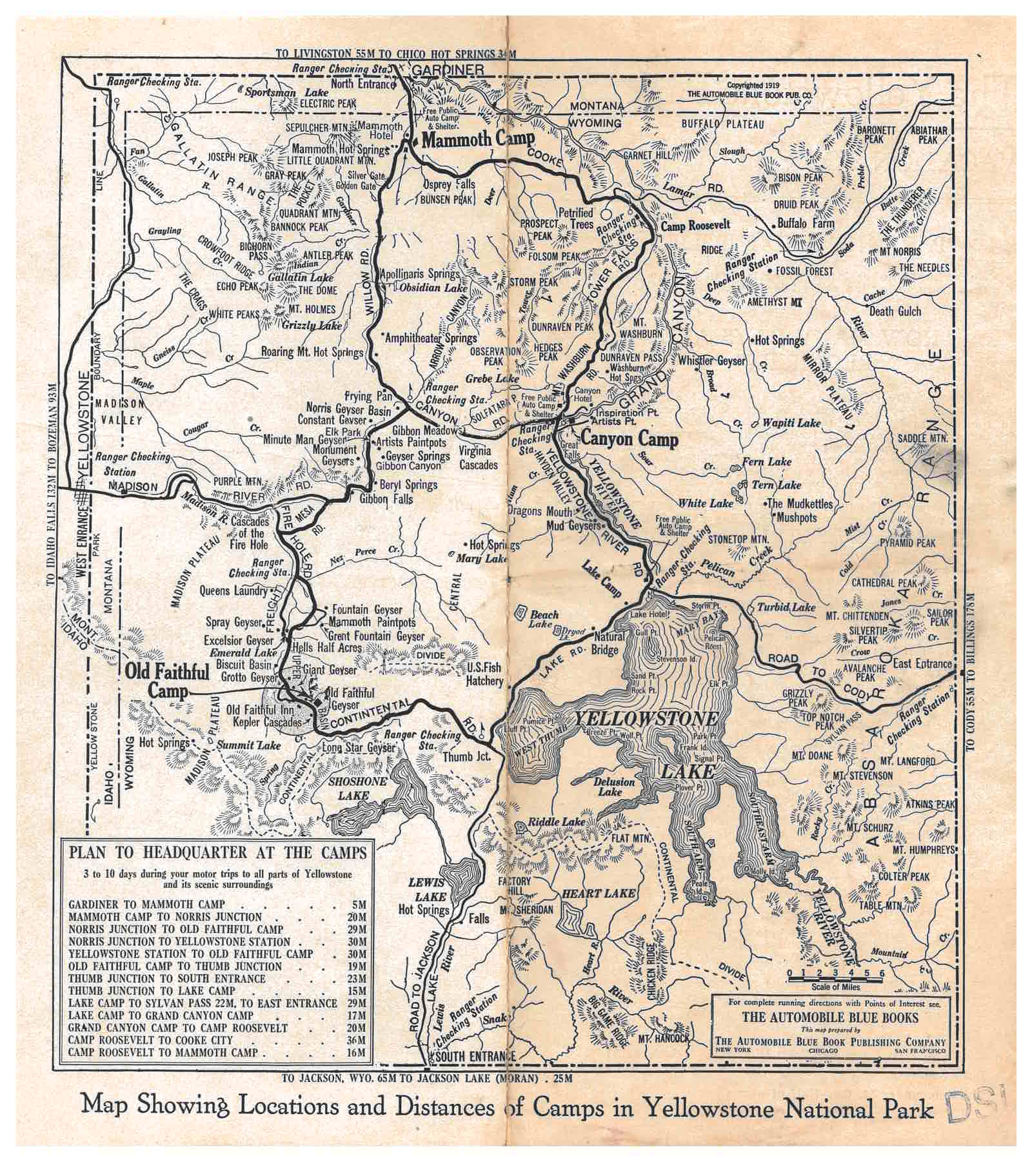

Old Faithful Camp, Mammoth Camp, and Canyon Camp (also sometimes referred to as Grand Canyon Camp) were the three main camps mentioned in this brochure. However, the map below appears to indicate two additional camps named Camp Roosevelt and Lake Camp.

As shown on the map, each camp was situated along a park roadway and nearby areas of interest, such as Old Faithful Geyser, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and Mammoth Hot Springs. The camps provided lodging, food, and entertainment for guests with an atmosphere described as “clean, informal and pleasurable.”

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [11-12], Map provided by Automobile Blue Book Publishing Co. showing the locations and distances of Camps in Yellowstone National Park.Visitors had the option of purchasing tickets at a Park Entrance or from “outside agencies.” As noted on the front cover, information offices were found in various cities: Livingston, MT, Salt Lake City, UT, Pocatello, ID, Yellowstone Station, MT, Cody, WY, and Denver, CO.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [11-12], Map provided by Automobile Blue Book Publishing Co. showing the locations and distances of Camps in Yellowstone National Park.Visitors had the option of purchasing tickets at a Park Entrance or from “outside agencies.” As noted on the front cover, information offices were found in various cities: Livingston, MT, Salt Lake City, UT, Pocatello, ID, Yellowstone Station, MT, Cody, WY, and Denver, CO.

The park offered three-, four-, or seven-day tickets and half-price tickets for children under age 12. Tickets included both lodging and meals, though it appears to have been possible to pay separately for these amenities as well. There was even a separate cost for a bath. If visitors did not use a portion of their tickets, they had the option of redeeming that portion upon exiting the park.

The summer camps provided dining halls and social assembly halls for guests to use during their stay. These buildings were situated in the center of the camp along with the camp’s business headquarters. Surrounding the central buildings were the sleeping accommodations. These were nestled beneath fir and pine trees to create “a ’tent city,’ or village of cozy, electric-lighted canvas bungalows or private sleeping rooms.” Guest accommodations included one, two, or four sleeping rooms.

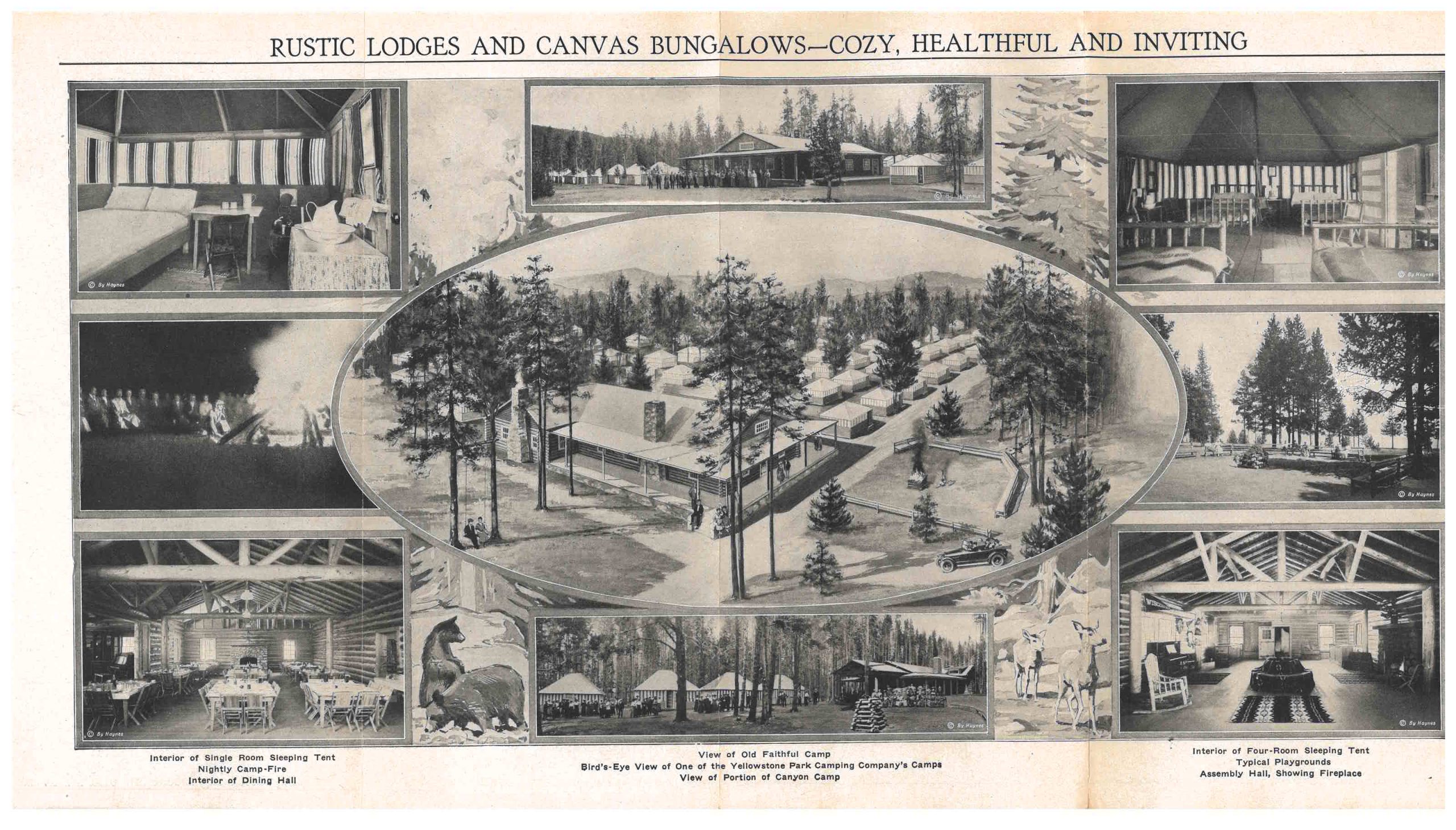

Camp buildings were laid out in an avenue style design. The avenue grid is visible in an aerial view of one of the camps shown below (center). The collage of images below also shows various buildings at Old Faithful Camp (center, top) and Canyon Camp (center, bottom).

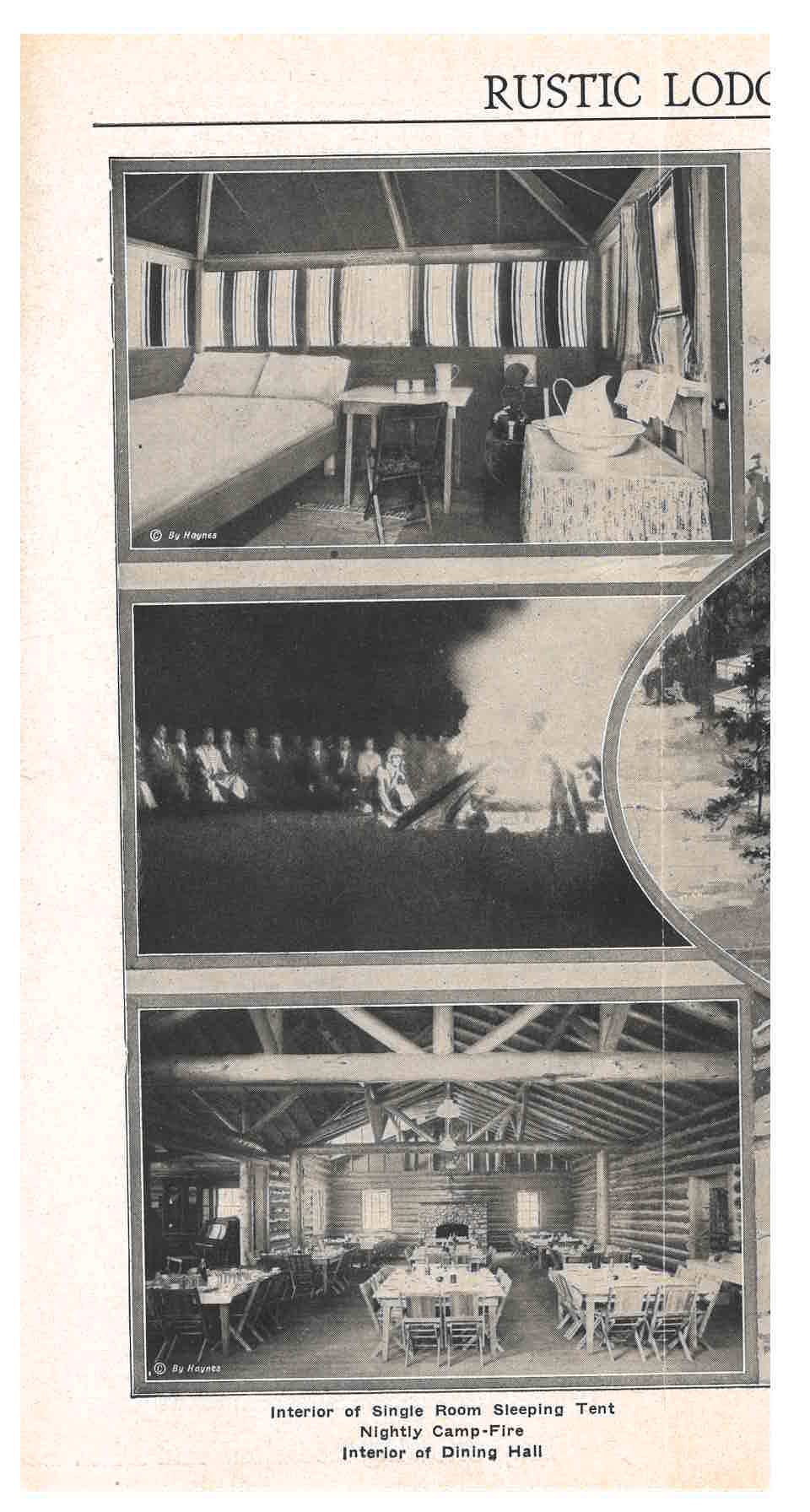

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [4-7], collage of images showing aerial view of one of the Camps in the center surrounded by images of single room sleeping tent interior, campfire, dining hall interior, Old Faithful Camp, Canyon Camp, four room sleeping tent interior, playgrounds, assembly hall interior, and wildlife.The sleeping tents were framed, floored, and wainscoted. Images of the furnishings appear simple, such as a table, chair, washstand with pitcher and bowl, and a full-size bed. No cots were used. A wood burning stove provided heat for each tent.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [4-7], collage of images showing aerial view of one of the Camps in the center surrounded by images of single room sleeping tent interior, campfire, dining hall interior, Old Faithful Camp, Canyon Camp, four room sleeping tent interior, playgrounds, assembly hall interior, and wildlife.The sleeping tents were framed, floored, and wainscoted. Images of the furnishings appear simple, such as a table, chair, washstand with pitcher and bowl, and a full-size bed. No cots were used. A wood burning stove provided heat for each tent.

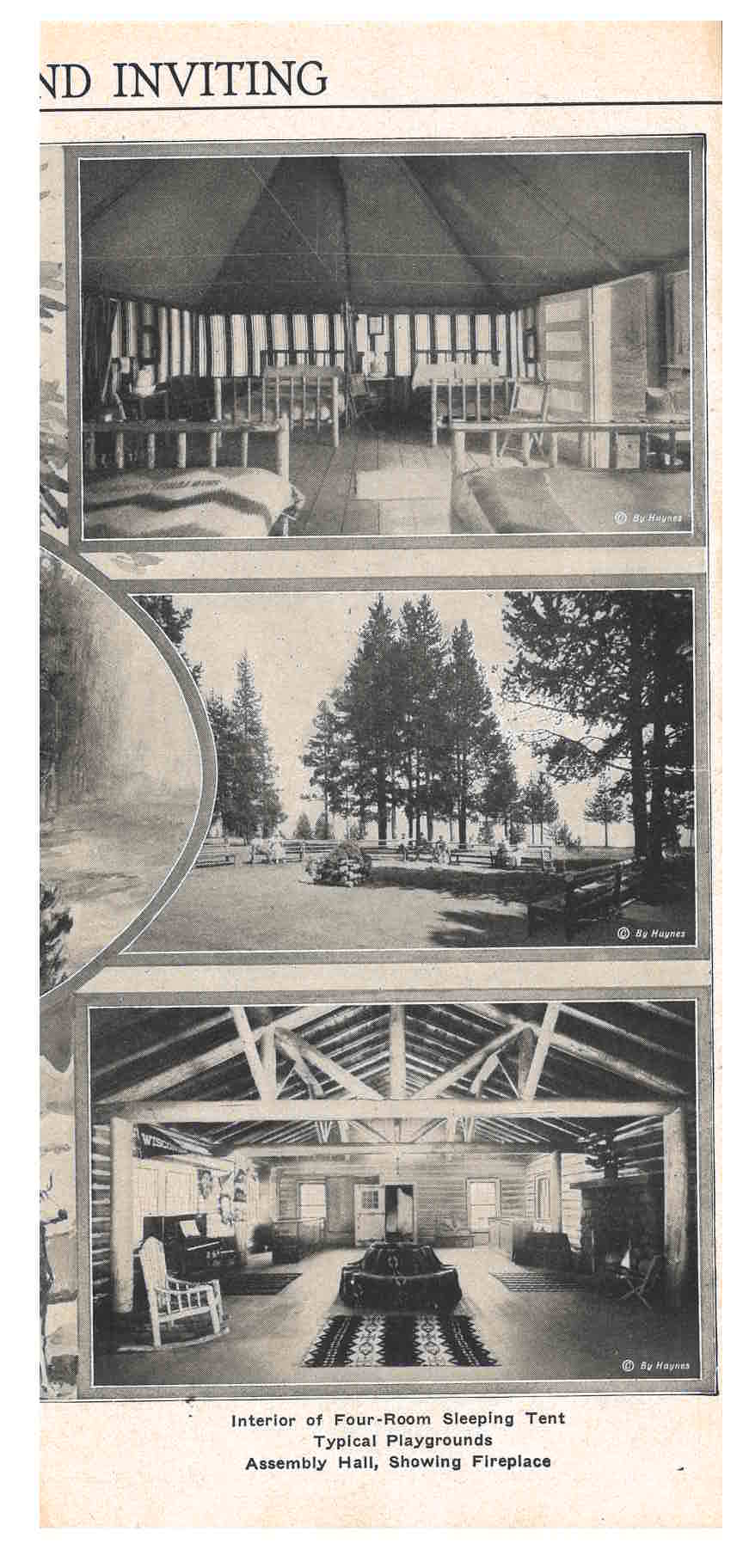

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered page [7], interior of four room sleeping tent, playgrounds, and assembly hall with fireplace.Meals were served in the dining hall located at each camp. The dining hall in the image below (bottom) shows several tables with a fireplace. Daily evening entertainment was also available. This included such activities as campfires (below, middle), music, dancing, and popcorn feasts.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered page [7], interior of four room sleeping tent, playgrounds, and assembly hall with fireplace.Meals were served in the dining hall located at each camp. The dining hall in the image below (bottom) shows several tables with a fireplace. Daily evening entertainment was also available. This included such activities as campfires (below, middle), music, dancing, and popcorn feasts.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered page [4], single room sleeping tent interior, campfire, and dining hall interior.Visitors had the option of remaining at one camp for their entire vacation or lodging at multiple camps, especially if they wanted to see a wider portion of the park. The title of this catalog encourages visitors to bring their own automobile, and according to this brochure, each park provided guest parking areas with gasoline and oil available.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered page [4], single room sleeping tent interior, campfire, and dining hall interior.Visitors had the option of remaining at one camp for their entire vacation or lodging at multiple camps, especially if they wanted to see a wider portion of the park. The title of this catalog encourages visitors to bring their own automobile, and according to this brochure, each park provided guest parking areas with gasoline and oil available.

Camp staff were young people, mainly college students and teachers. As a free service, guides were available to lead a sightseeing day trip. Of course, visitors also had the option to venture out on their own. Perhaps they marveled at the natural beauty of the scenery as they drove along the hundreds of miles of roads or took a detour to enjoy one of the scenic approaches to the park. A map of the main routes to Yellowstone National Park is included in this brochure.

Some visitors might have been lucky enough to snap photos of the wildlife, such as bear, elk, deer, antelope, or buffalo. Hopefully any pictures were taken from afar!

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [2-3], general information about the Camps and Park.Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919) by Yellowstone Park Camping Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Yellowstone Park Camping Co., Livingston, MT. Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919), unnumbered pages [2-3], general information about the Camps and Park.Yellowstone National Park in Your Own Automobile (1919) by Yellowstone Park Camping Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Diving into the Zoological Gardens and Aquariums Ephemera Collection

The Zoological Gardens and Aquariums Ephemera Collection began as an all-call for interesting memorabilia relating to zoos, aquariums, gardens, or the societies that support such institutions. Many items were received, cataloged, and filed in cabinets located in the former library space at the National Zoological Park (Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC). A previous attempt was made to rehouse, organize, and digitize parts of the collection, but the project was left incomplete. The collection was eventually moved to the National Museum of Natural History Library so that the items could be properly archived and stored.

“Illustrated Guide and Catalogue of Woodward’s Gardens” (1873), bearing signature of Smithsonian ornithologist Robert Ridgway.

“Illustrated Guide and Catalogue of Woodward’s Gardens” (1873), bearing signature of Smithsonian ornithologist Robert Ridgway.

When I arrived at the Natural History Library’s main location at the beginning of the summer of 2023 for my internship, I got my first look at the Zoological Gardens and Aquariums Ephemera Collection. After performing a short survey assessment of the collection, my supervisor Bonnie Felts and I came up with a game plan to rehouse and document the collection. During our discussion, we decided that our end goal for the project was to conserve as many of the items as possible and make them discoverable for future research.

View-Master reel for the San Diego Zoo.

View-Master reel for the San Diego Zoo.

I found that the collection included a wide variety of diverse pieces from various time periods. While some items do not have a date included on the object, the collection appears to range from about 1873 to 2008 according to the items that do have dates listed. The objects in the collection are mainly guidebooks, maps, pamphlets, postcards, and reports, but there are also disparate items such as stickers, coloring books, and view master slides. As I went through the collection, it was interesting to review the objects that people thought important enough to save. Some of these items are over a hundred years old and represent a piece of history not only to the Smithsonian, but to the people who spent time at these institutions.

“Popular Official Guide to the New York Zoological Park” in a new enclosure.

“Popular Official Guide to the New York Zoological Park” in a new enclosure.

As someone who is just stepping foot into the library and archives space, it was an incredible learning experience to be able to work with this collection. It was empowering to take part in the hands-on work of rehousing the collection mainly because it was a collaborative experience. Instead of being given a concrete task list, my supervisor was open to my input on how best to conserve and house the various objects in the collection. We worked together to create a system not only to rehouse the items, but to make sure those items were able to be found later in our finding aid. My favorite piece of the rehousing process of the internship was learning how to make a four-flap enclosure for some of the larger delicate artifacts. The hands-on learning of rehousing the collection into archival mylar, folders, and boxes, along with the creation of the finding aid and four-flap enclosures are skills that I will be able to take with me into the next steps of my career.

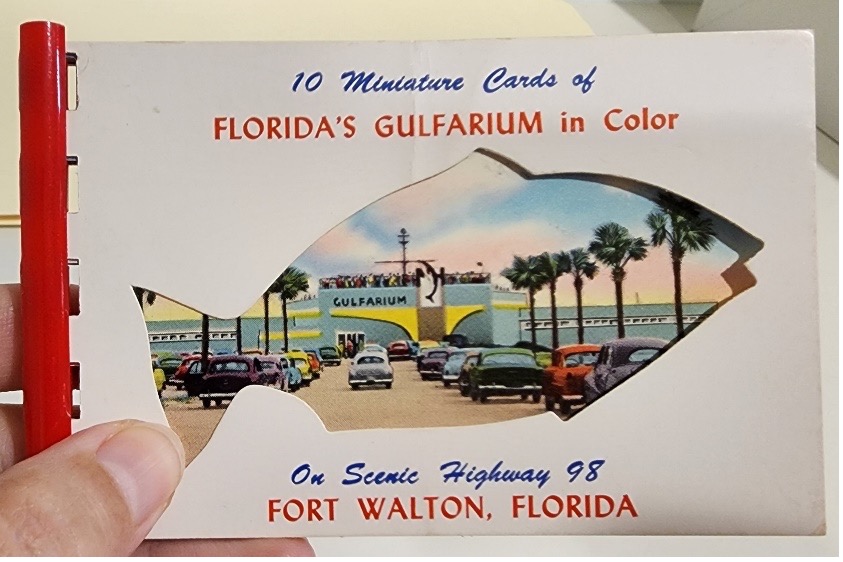

“10 Miniature Cards of Florida’s Gulfairum in Color” from Fort Walton, Florida.

“10 Miniature Cards of Florida’s Gulfairum in Color” from Fort Walton, Florida.

Overall, my experience with my Smithsonian Library and Archives internship was incredibly informative. Not only were the skills that I learned important, but the experience of working in a library or archive space was key to my educational growth. Through the internship I gained introspection that this was the correct step for my future and my career. Having this opportunity and space to learn and grow gave me incredible insight into how important these spaces are for future generations and why I want to be a part of them.

In Search of the Perfect Blue

The color blue has had a long history in the Western world. The ever-changing role of blue has been used in bookbinding and the book arts to color manuscripts, maps, and scientific illustrations. Colorants used in inks, paints, and dyes have come from a variety of natural sources, including clays, gems, plants, and insects. Blue pigments were first made from imported minerals from Central Asia, eventually shifting to local resources within Europe. The exhibition, Nature of the Book, explores the use of natural materials in bookmaking during the hand-press period (1450-1850), touching on how this rare pigment was initially reserved for religious works, later changing focus to favor European royalty and nobility. As blue’s color gained popularity for a wider audience by the end of the 18th century, new shades and formulas were created; in fact, the first synthetic pigment was a blue that offered greater access to a more affordable version.

The earliest and rarest blue was obtained from the precious stone lapis lazuli, also known as lazurite. The mineral, primarily mined in Afghanistan, was for centuries shipped a great distance into Europe through Venice. It was ground to a powder and laboriously processed to create a vibrant pigment. Because it was so costly, artists chose to use it sparingly. The calcite content in lazurite, a silicate mineral, was positively identified by x-ray fluorescence in a blue paint sample on parchment in a 15th-century illuminated philosophical work from the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. This reveals that the pigment was only used as a top coat and provides evidence of its value. Europeans called this color Ultramarine because of its brilliant resemblance to the sea and, as such, the color remained a favorite and was most extensively used in hand-colored manuscripts through the 15th century.

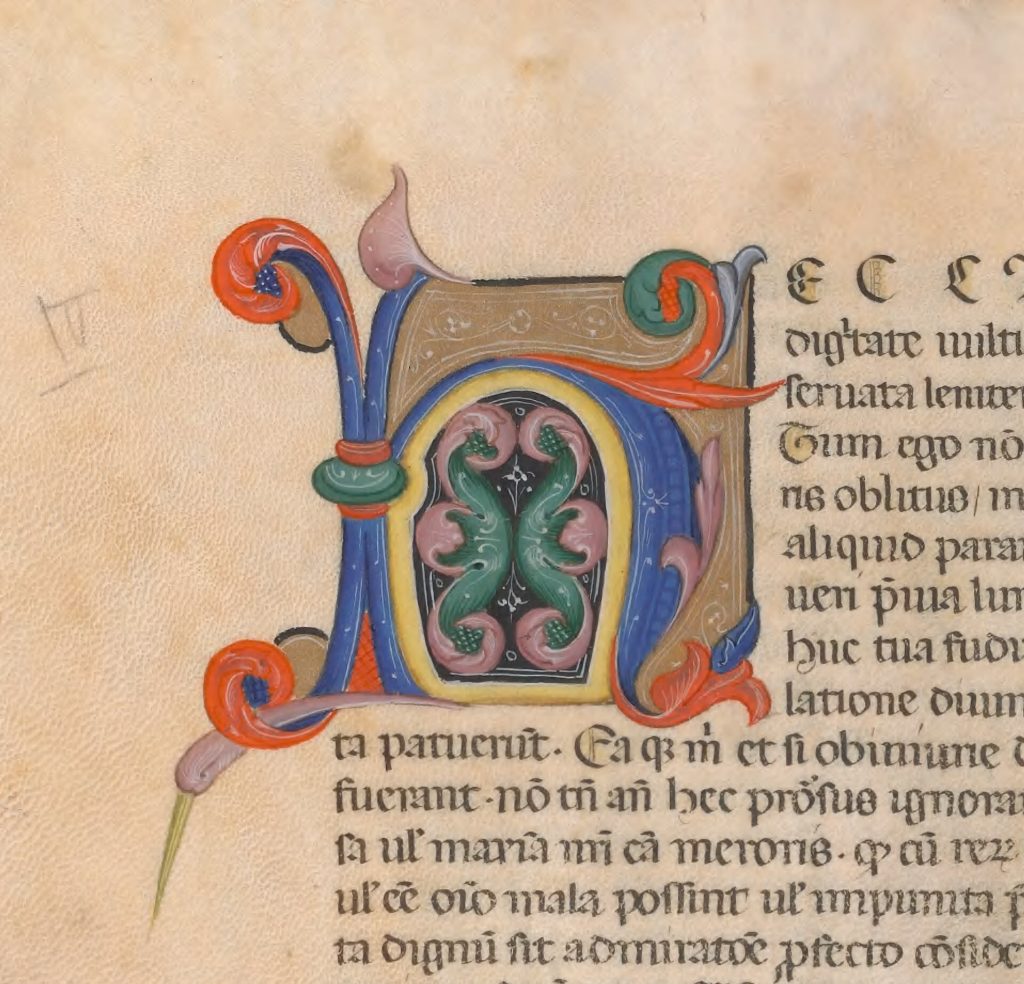

Detail. Boethius, On the Conservation of Philosophy, 15th century.

Detail. Boethius, On the Conservation of Philosophy, 15th century.

Azurite, a blue copper ore, was a less expensive alternative to rare lapis lazuli. Though available by trade from sources as far as Asia, azurite was popularly used in European illustrations into the 17th century owing to the convenience of some local regional mining. Ultramarine and azurite blue were used to beautify and convey prestige or value in books; the symbolism of blue represented the mystical powers of sky and water. Combined with the relative expense to achieve this, the use of blue was often reserved for those of high-ranking status, as featured in a hand-colored 1604 Spanish petition for nobility. The blue pigment used in the illuminations has been positively identified as azurite. The bound manuscript is displayed alongside a specimen collected from Germany and loaned from the Department of Mineralogy in the National Museum of Natural History.

Detail. Petition for noble status (manuscript), Spain, 1604.

Detail. Petition for noble status (manuscript), Spain, 1604.

Azurite with malachite and siderite, Germany. NMNH B7994, National Museum of Natural History. Gift of Carl Bosch.

Azurite with malachite and siderite, Germany. NMNH B7994, National Museum of Natural History. Gift of Carl Bosch.

As subject matter expanded with the development of printing, books covered a multitude of topics by the 18th century. The desire to use blue pigments for illustration grew with the rapid pace of book production. By 1724 the first modern artificially produced pigment that offered a more economical option, Prussian Blue, was developed for use. Global exploration during that period stimulated the production of many scientific works that required precise coloring for illustrations of the natural world for an insatiable academic audience. Illustrations from the first fully illustrated and comprehensive study of the flora and fauna of North America were drawn, and many of them etched, by author and naturalist Mark Catesby. Some illustrations in Catesby’s work are hand-colored using Prussian blue – its iron content recently identified through pigment analysis by conservation scientists at the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute – to enhance the colors of the Carolina Parakeet and the Painted Finch, birds not yet known to Europeans. Accurate descriptive coloring from that period has continued importance with current research as some species within the natural world are now extinct.

Visitors are encouraged to visit the books and artifacts representing this story of blue as well as other specimens and collections illustrating the varied sources of dyes, pigments, and inks featured in the Nature of the Book exhibition, located on the first floor of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis). Mark Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. London, 1729-1747.

Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis). Mark Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. London, 1729-1747.

Detail. Painted Finch (painted bunting, Passerina ciris). Mark Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. London, 1729-1747.

Detail. Painted Finch (painted bunting, Passerina ciris). Mark Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. London, 1729-1747.

Processing Personalities: Ephemera Research at the AA/PG Library

It’s interesting to think of how much of our everyday culture goes unnoticed, lost to time and simple decomposition. The newspaper someone tossed yesterday turns to mush in a landfill pile. The gilt invite you saved from your alma mater’s 15th reunion is lost in a pile of documents, kids’ art projects, and bills. The sticky note with your to-do list gets stuck to the bottom of your shoe and wears away as you walk to work one day. We often don’t take the time to think about these little pieces of paper, these tiny fragments of memory and thought that we churn out every single day, though these can very often be the most crucial clues about who we are.

The value in the Art & Artists’ Files at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library (AAPG) lies in their attention to these everyday ephemera, the things left behind and that, when pieced together in a variety of different ways by staff members and researchers, tell a myriad of intimate and often novel stories of artists and institutions. Each file includes ephemera on a particular subject (an artist, corporation, or subject): exhibition announcements, clippings, press releases, brochures, pamphlets, photographs, resumes, artist’s statements, exhibition catalogs, and more, a panoply of snippets from the lives and works of American artists (with an expansive definition of “American”). For some of the lesser-known artists in the Files, these small slips of paper are the only available materials we have for research and study.

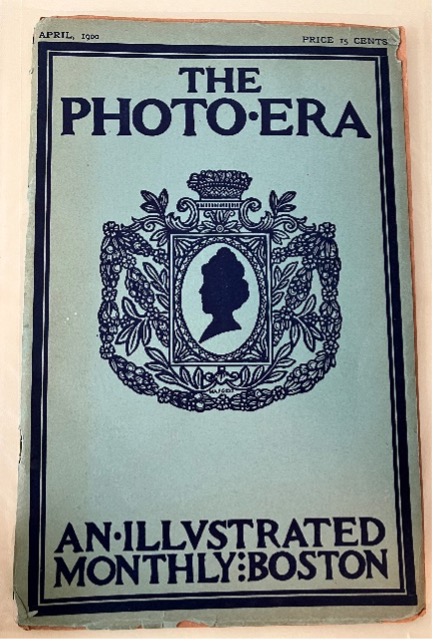

The beautiful mint green cover of a copy of Photo Era magazine from 1900, found amongst the NMAH Photo History ephemera.

The beautiful mint green cover of a copy of Photo Era magazine from 1900, found amongst the NMAH Photo History ephemera.

As a Summer Scholar intern at AA/PG, I had the opportunity to sort through seventeen boxes of woefully unorganized ephemera, attempting to merge the subject files on photographers and inventors from the Photographic History Collection of the National Museum of American History with AA/PG’s Art & Artists’ Files. The types of ephemera in these boxes ranged from patents for photographic technology (from multiple countries), photocopies of master’s theses, photographs and slides, and handwritten letters to whole magazines, exhibition catalogues, self-published books, and anything else on paper you can think of. I knew that attention to detail and scrupulous documentation would be necessary for keeping track of everything for this project, so I set five goals for the process and result:

- Clear out the backlog of old ephemera held by the AA/PG

- Add relevant and potentially valuable research material to Art & Artists Files

- Gain experience processing “archival” or ephemera materials.

- Create accessible records for wider range of photographic artists in the collection.

- Establish a repeatable personal process for doing this sort of work if it comes across in my career in the future.

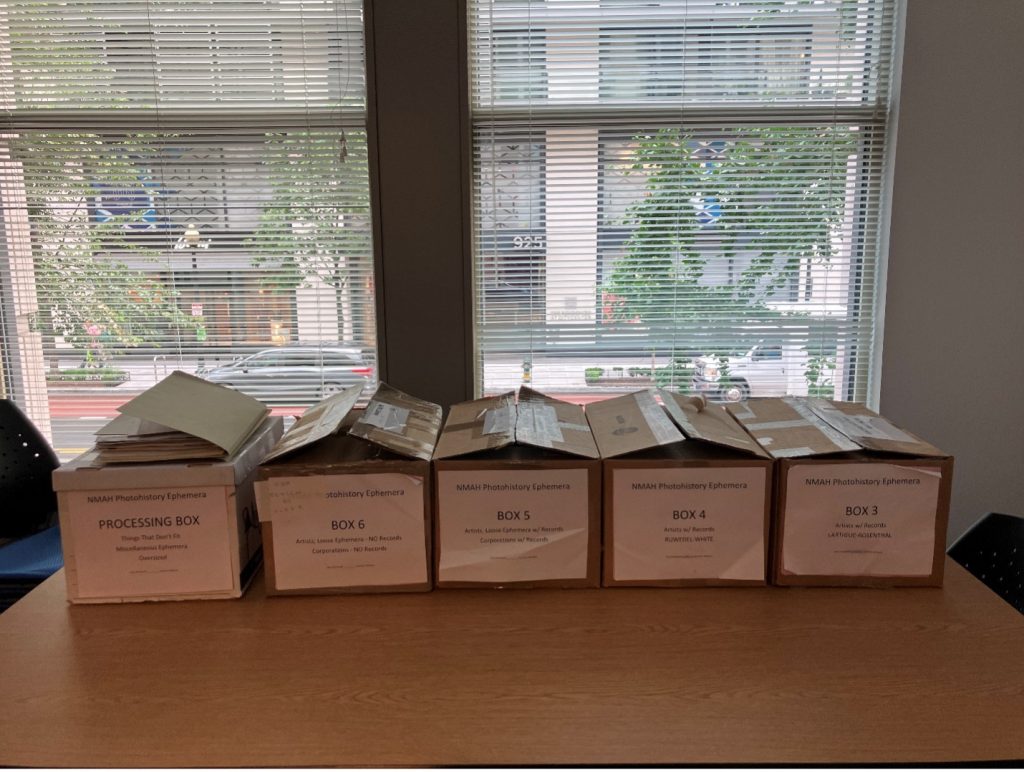

Some of the many storage boxes for my processing of the NMAH ephemera (there were originally 17!)

Some of the many storage boxes for my processing of the NMAH ephemera (there were originally 17!)

The main challenges I faced when attempting to achieve these goals were the disorganization of the boxes and undoing the partial processing done in the past, which made finding out what we had and where to put it challenging; establishing the criteria for what to keep and what to get rid of; and filing hundreds of physical materials into our folders in a way that kept everything cohesive and accessible.

I set two step-by-step plans in place, one to follow for ephemera whose subject was in the Art & Artists’ Files online database and one for ephemera whose subject was new or not in our files yet. We could slot ephemera for records we did have right into our subzero room of file cabinets, while the ephemera for records we didn’t have could be set aside into boxes to be looked over later. Because there were over 850 individual subjects represented in the boxes, I had to develop some strict criteria for what to keep and what to weed, based on what was already in the AA/PG collections. Many libraries face issues with space, and there are already thousands of files in the Art & Artists’ Files collection, so it was time to make some tough choices. I decided on the following guidelines:

- Is the artist/corporation American?

- Do they supplement an existing file in a novel/important way?

- Is the ephemera folder too scientific or is it appropriately art-related?

- Is the piece of ephemera in good condition?

- Is the piece of ephemera rare or special in some way?

At the end of the day, the AA/PG Library collects expansively, meaning that many of the things I’d marked for weeding ended up finding a happy place in the collections instead. After doing an unexpected amount of labor to type every piece of relevant information about the materials in my master spreadsheet, rearrange everything in the boxes, and put the ephemera away in the filing cabinets, I was excited to finally have completed my project. As with many archival processing-adjacent projects, there’s still one box left for my supervisor to review after I’m gone. Through this experience, I not only learned new skills in processing diverse types of materials but also improved as a project manager. The independence that the librarians at AA/PG gave me to explore different methods for completing my project helped me gain self-confidence by allowing me to piece together my library skills in a new and challenging environment. When I started work on my processing project at the Smithsonian’s American Art and Portrait Gallery Library, I never expected to gain a practical and much-needed lesson in mindfulness—in appreciating these tiny moments, encapsulated in ink, cardstock, paper, and graphite—but I quickly learned that its important to appreciate and let myself be excited by seemingly mundane, everyday things.

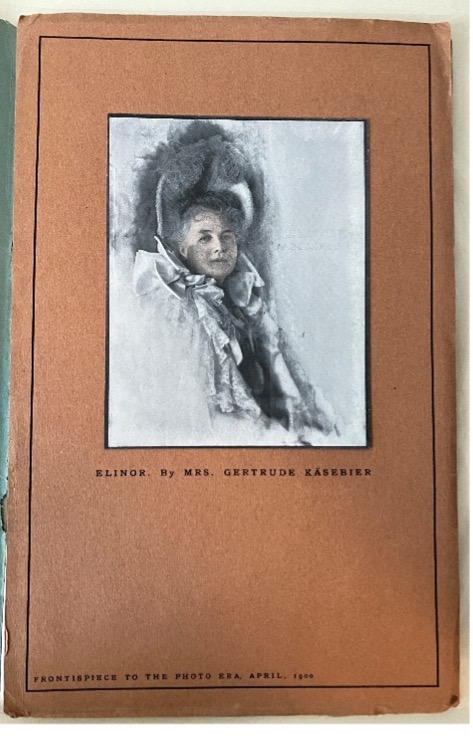

A hand-coloured photograph (zoom in on her face!) by Getrude Kaesebier, a 19th-century woman photographer whose file is in the AA/PG Art & Artists’ Files

A hand-coloured photograph (zoom in on her face!) by Getrude Kaesebier, a 19th-century woman photographer whose file is in the AA/PG Art & Artists’ Files

If you’re interested in learning more about photography, its history, and its major players (or any other medium of art and architecture), I highly suggest checking out all of my newly added Art and Artist files at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library.

Traveling Trunks Available for Borrowing

As we gear up for the upcoming school year, the Education Team at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives wants to remind you of our growing fleet of Traveling Trunks! These interactive educational resources are available for teachers and schools across the country. This program is free of charge and trunks can be lent for up to four weeks.

We have been working hard to add more themes over the past year and currently have three different trunks to lend, with a fourth available in October.

- Nice Tú Meet You focuses on Latinx cultures from Central America and the Caribbean through the regions’ music and stories. Four fictional teen narrators tell their families’ histories and how it connects to their current lives in America.

- Extra and Ordinary is narrated by a fictional archivist tasked with researching for a new exhibit. Learners will have the chance to look at the archivist’s research – recreated letters, pictures, and objects from the Smithsonian collection – about twenty women living from 1785-2013 in the United States.

- Flights of Friction: Fact or Fiction? (coming September 2023) takes learners back to the 19th century to uncover sensational mysteries of the past. Guided by a passionate and curious librarian, learners will use information literacy skills to look into the legitimacy of authors, sources, newspapers, and their stories.

- Art History Mystery (coming October 2023) partners with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden to bring learners a clue-style journey of uncovering hidden messages in art, based on activism.

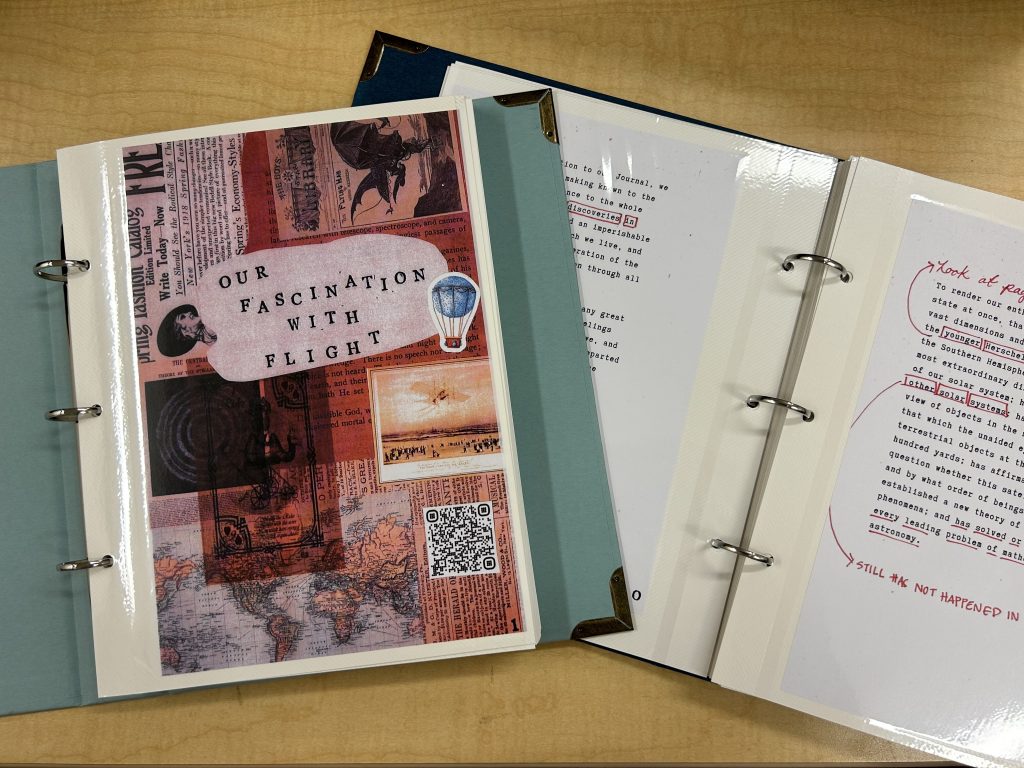

Materials from the “Flights of Friction: Fact or Fiction?” TravelingTrunk.

Materials from the “Flights of Friction: Fact or Fiction?” TravelingTrunk.

Traveling Trunks do rely on users being able to scan QR codes and watch videos. We recommend your group has at least four Wi-Fi or cellular-enabled smart devices to engage in this program.

Interested in bringing a Traveling Trunk to your school? Learn more about the program and see how to reserve a trunk on our Education webpage.

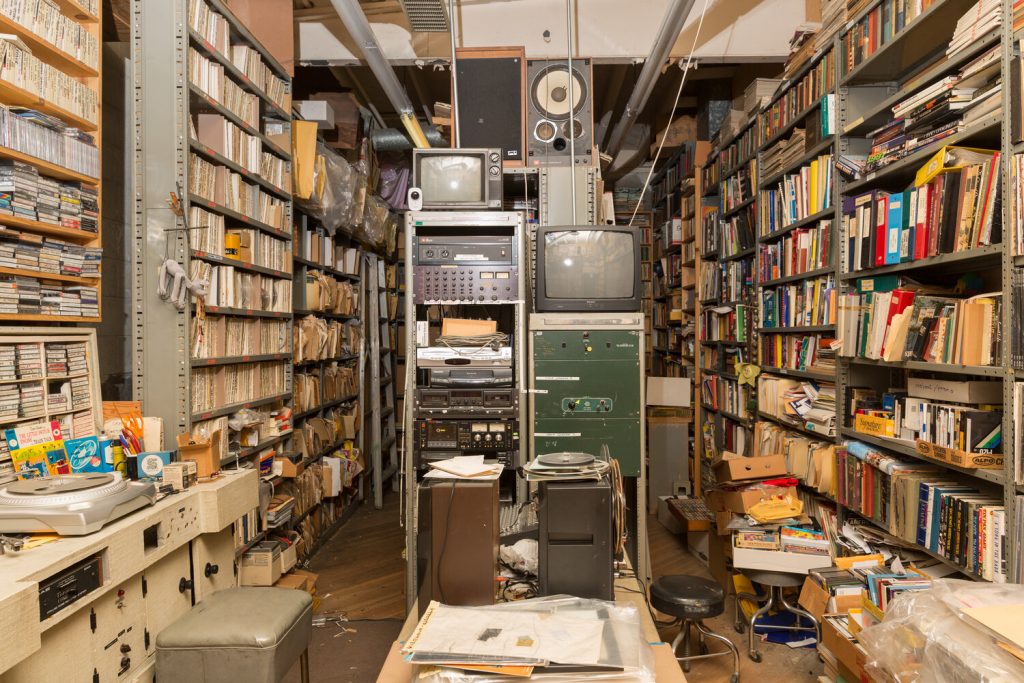

Through the Loupe: Rick Prelinger

This is the fifth in a series of ongoing blog posts from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI), spotlighting the labor of Smithsonian media collections staff across the Institution, and the first to feature a past Smithsonian worker. Among several current professional roles, former Smithsonian contract audiovisual consultant Rick Prelinger runs the non-profit Prelinger Library in San Francisco with his partner Megan.

AVMPI Co-Presents: Radio Preservation Task Force

On April 30th, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ pan-institutional Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI) co-presented the fourth day of the Radio Preservation Task Force (RPTF) conference with the Library of Congress. The theme of the 2023 conference was “A Century of Broadcasting: Preservation and Renewal,” and Day Four’s proceedings were titled “Sunday at the Smithsonian,” comprising a radio/sound art performance, presentations by Smithsonian staff about SI radio collections, and a conference-capping ‘Listening Party’ that shared archival radio clips from a dozen international archives. A brochure of the program, designed by AVMPI’s Video Preservation Specialist and go-to graphic designer, Brianna Toth, can be accessed here.

Included in the day’s array of radio-related and Smithsonian-proud programming was a ‘response’ conversation between sound performers Anna Friz and Jeff Kolar with audiovisual archivist, and recent Emeritus Professor of Film and Digital Media at the University of California – Santa Cruz, Rick Prelinger. For over 40 years the self-described “library experimenter” Prelinger (@footage) has been a visionary figure in the field of film archiving and information science. The Prelinger Library he founded with his partner Megan in 2004 should be at the top of your list of places to visit when in San Francisco. Prelinger’s career has spanned working as a typesetter, running his own stock footage licensing company, working as an archivist at The Comedy Channel and HBO, serving as a board member and contributor to the legendary Brooklyn magazine Stay Free!, making films and footage performances, and teaching at several universities. I have been fortunate to know Rick personally since the late 2000s, previously encountering and obsessing over his commercially-released VHS compilations of incredible ephemeral films and television commercials when I worked at Chicago’s Facets Video in 1999. However, there was one professional role of Prelinger’s I was unaware of and, during the RPTF’s April 30th morning on-stage sound check, Rick disclosed it: he once worked for the Smithsonian (!?).

Rick Prelinger (at left) with this blog post’s author (at right).

Rick Prelinger (at left) with this blog post’s author (at right).

Smithsonian Institution – Office of Telecommunications

Frankly, I had a hard time fully concentrating on the remainder of the day’s activities after Rick recalled a paid gig working for the Smithsonian’s Office of Telecommunications (OTC), around 1989. The Office of Telecommunications was an iteration of the Smithsonian’s in-house audiovisual production entities, which began in the 1960s under the initiatives of Secretaries Leonard Carmichael and (far more aggressively) S. Dillon Ripley. In 1976 the media production activities of the Smithsonian’s Office of Public Affairs were formally reorganized as the OTC, and New York television producer Nazaret ‘Chick’ Cherkezian (previously at New York University, then National Educational Television) was appointed its director. One particularly mythological photo of Cherkezian held by Smithsonian Institution Archives has ‘Chick’ standing in front of a 1-inch VTR video rack and exuding a no-nonsense attitude.

Photograph included in the transcript of the Nazaret Cherkezian Oral History Interview by John Peterson, December 3, 1986, in Smithsonian Institution Archives. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 9541, Box 1.

Photograph included in the transcript of the Nazaret Cherkezian Oral History Interview by John Peterson, December 3, 1986, in Smithsonian Institution Archives. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 9541, Box 1.

Cherkezian served as OTC Director from 1975 until 1986 and under his tenure OTC produced radio programs, exhibition videos, and a string of documentary films that won multiple awards, including four Emmys (for Celebrating a Century: The 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, directed by OTC staff filmmaker Karen Loveland) and a string of CINE Golden Eagles, among others. Cherkezian set Institutional program priorities for OTC productions, brought media-wary curators into the fold across disciplines, built a staff of 14 full-time producers, and conceived the successful television programs, Smithsonian World (1984-1991) and Here at the Smithsonian (1982-1989). Thanks to the Smithsonian’s Institutional Historian Pamela Henson, Cherkezian’s oral history from December 3, 1986 captures a great deal about Cherkezian’s era of the OTC.

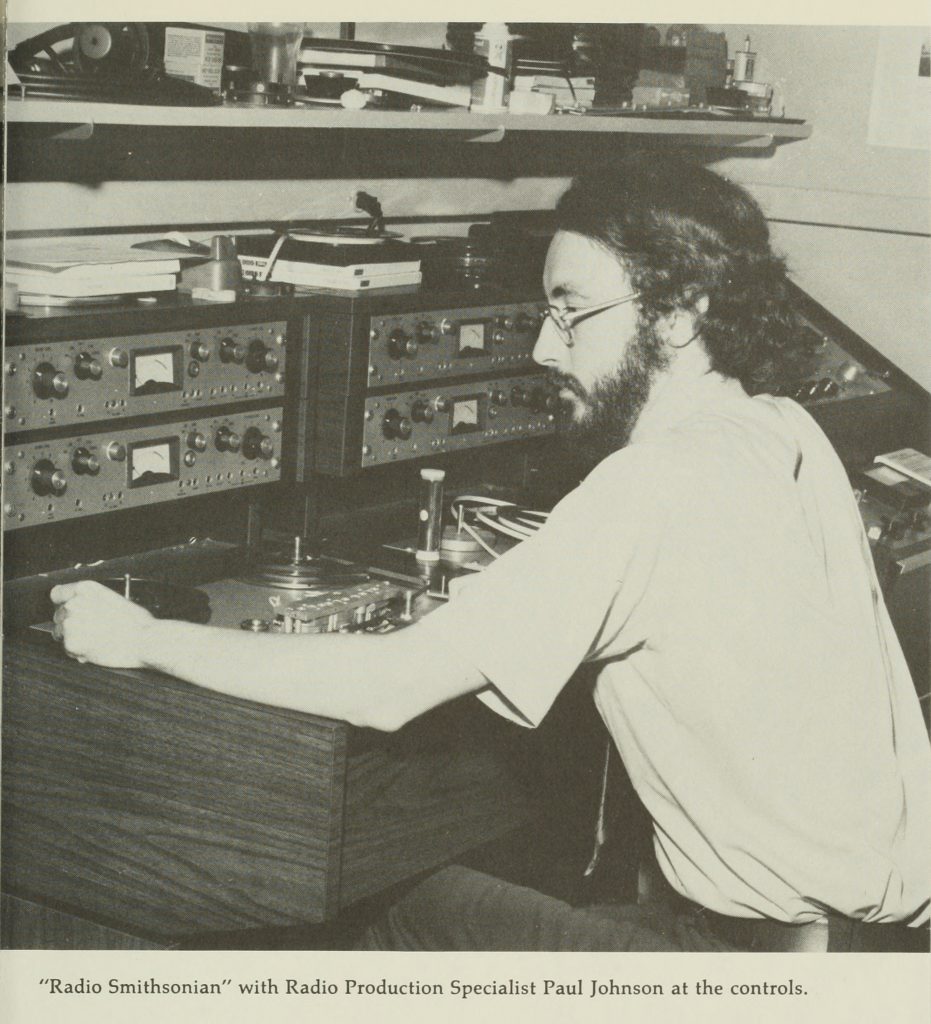

Cherkezian’s longtime ‘number two’ was OTC Associate Director Paul B. Johnson, who began as a Production Specialist on the Radio Smithsonian half-hour program in the early 1970s. Johnson, who appears at the helm of a pair of ¼” reel-to-reel audiotape machines on page 229 of the 1974 edition of Secretary Ripley’s annual report to Congress, Smithsonian Year, became OTC Director upon Cherkezian’s retirement, serving in the role until the division’s ultimate dissolution in 2002, when it was known as Smithsonian Productions.

“Radio Smithsonian” with Radio Production Specialist Paul Johnson at the controls. Image from: Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Year (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1974), 229.

“Radio Smithsonian” with Radio Production Specialist Paul Johnson at the controls. Image from: Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Year (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1974), 229.

Rick Prelinger: Smithsonian OTC Consultant

Prelinger grew up in the Washington, DC area, and as we talked during our “Sunday at the Smithsonian” sound check he recalled being dropped off by his parents on weekends to navigate the Smithsonian’s multidisciplinary exhibits. “I remember that they still had the pull-out stamp drawers,” Prelinger said, referring to Joseph Leavy’s innovative 1914 philatelic showcase that lasted over a half-century in the Arts and Industries building.

As a DC native, Prelinger evidenced a degree of pride about his contract work as a Smithsonian consultant for Paul B. Johnson’s OTC, where he conducted a holdings survey and assessment report on the division’s audiovisual collections. Exact recollected details were hazy, but maybe he still had a copy? Before Rick left the RPTF event early to spend some time with his sisters who still live in the area, I promised to badger him about finding that copy.

On May 10th, Prelinger emailed me:

So I looked into this. I prepared it in 1989 for the Office of Telecommunications; my contact was [OTC Associate Producer] Jean Quinnette. It isn’t in my existing backups from that period, which makes me wonder whether I even used a computer. I will bumble around my hardcopy files for this period, if I can find any, but no promises. I am recalling that the report mostly covered internally produced film for Smithsonian TV — more of the video news release variety than programs intended for longform broadcast. And I think that I looked in metal cabinets in a number of Museum units. This is a perfect example of material disappearing into the amnesic pit of the 1970s and 1980s.

Rick wasn’t able to find any digital trace of his consultancy work for the Smithsonian, but he later wrote again to me:

It is almost unbelievable, but I opened a box at random and my Smithsonian folder was at the top. It contained my long-winded report from 1992 (not 1989). I was paid $400 for this — the invoices for travel reimbursement (maybe even on the Trump Shuttle) are laughable.

Rick Prelinger’s Rediscovered ‘Smithsonian folder’

Thanks to FedEx and my neighborhood copy shop, I’m thrilled to upload and make available much of the Smithsonian audiovisual collections treasure that Rick’s ‘Smithsonian folder’ contains. Prelinger is a longtime board member of the Internet Archive, which is where this documentation appropriately now lives.

The most substantive document contained therein is the fourth revised version of Prelinger’s report to OTC, dated November 1992. A priceless time capsule snapshot of OTC in an era when its long-running major television series Smithsonian World and Here at the Smithsonian had wound down, the report focuses on the idea that OTC might license stock footage for revenue purposes. Prelinger’s analysis and recommendations in this regard are sheer expert, informed by his first-hand concurrent operation of the New York City-based Prelinger Associates, Inc., and this report is one of the most detailed explanations of the stock footage landscape and how the footage licensing industry operated in the 1980s and 90s.

As a good film archivist, Prelinger also makes excellent recommendations regarding selection, physical conservation, and environmental storage: Isolate best copies of finished productions and move them to controlled storage; Develop and institute a retention policy that eliminates redundant inferior-quality copies and generational elements that exist elsewhere in better and more finalized versions; Research legal status of materials; Liaise with other Smithsonian audiovisual collections managers at museum units. All of these suggestions ring true as activities of our AVMPI project, in accordance with best practices of the field, and it’s refreshing to read that Prelinger communicated them to the Institution so long ago.

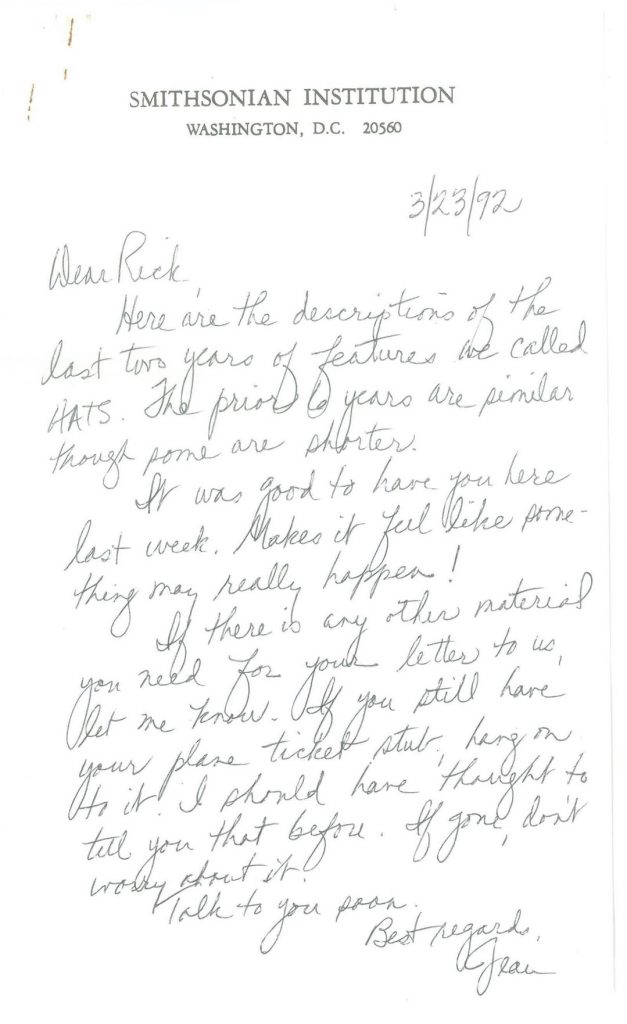

Prelinger’s ‘Smithsonian folder’ also holds a handwritten note on xeroxed Smithsonian stationery from OTC’s Jean Quinnette. The note conveys a certain familiar honesty about the slow pace of the federal government: “It was good to have you here last week. Makes it feel like something may really happen!”

Handwritten letter from Jean Quinnette to Rick Prelinger, dated March 23, 1992.

Handwritten letter from Jean Quinnette to Rick Prelinger, dated March 23, 1992.

As Quinnette’s note references, Prelinger’s ‘Smithsonian folder’ also includes valuable original OTC documents with synopses, episode details, and air dates for its Smithsonian World and Here at the Smithsonian… (HATS) television programs. Both are series for which Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is currently digitizing videotape ‘master’ copies, with plans to stream them online in the coming year. These original promotional materials will helpfully inform our cataloging of both programs.

Several other film and video distribution brochures and a list of OTC-produced titles are also in Rick’s ‘Smithsonian folder,’ several of which contain the early-1990s OTC letterhead logo, which I have never seen before.

Office of Telecommunications logo, circa 1991.

Office of Telecommunications logo, circa 1991.

If Rick Prelinger’s stint working as a contract audiovisual archives consultant for the Smithsonian was, ultimately, a brief one, his impact can yet be seen through the many current SI audiovisual archives professionals who consider Rick’s advocacy and career as essential to the archives field and a model to aspire to. Thank you, Rick!

Sound artist Jeff Kolar, archivist Rick Prelinger, and UC-Santa Cruz faculty Anna Friz in conversation at the Radio Preservation Task Force’s “Sunday at the Smithsonian” event, co-presented by SLA and held in the Baird Auditorium, April 30, 2023.

Sound artist Jeff Kolar, archivist Rick Prelinger, and UC-Santa Cruz faculty Anna Friz in conversation at the Radio Preservation Task Force’s “Sunday at the Smithsonian” event, co-presented by SLA and held in the Baird Auditorium, April 30, 2023. Sonic Strategies in the Library

This exhibition and blog post were curated and written by Joana Stillwell.

Sonic Strategies in the Library accompanies the newly opened exhibition Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Musical Thinking, by Curator of Time-Based Media, Saisha Grayson, focuses on video art that uses sonic strategies including scores, improvisation, and interpretation, as well as styles, structures, and lyrics that speak to American life. The works selected for this accompanying exhibition at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library (AA/PG) include books from the collection as well as materials from the artist files. Nine selections ranging from the early nineteenth century to the 2010s reveal the ongoing and evolving relationship between visual art and music and sound.

Music: A Mere and Colorful Memory

Before the advent of recorded sound, music was a medium only available to a live audience, and only recollected orally, or venerated in the visual arts. Painting was considered the main art in the early twentieth century and its ability to capture the essence of music was the focus of Luna May Ennis’ Music in Art (1904). This is embodied by the beautiful red and gold cover which centers a ribboned and stylized painter’s palette, while the border is compiled of different types of stringed instruments, pan flutes, and white flowers. The book is organized among themes of myth and enchantment, youth and love, worship and are punctuated by illustrations by Donatello, Raphael, Rubens, and more. The book reads as art historical analysis but through the perspective of a viewer trying to relive “the sound [that has died] with the vibration of the strings [and] with the breath of the singer becom[ing] a mere memory.”

Analogous Scale of Sounds and Colours from George Field’s Chromatics

Analogous Scale of Sounds and Colours from George Field’s Chromatics

George Field’s Chromatics, or, an essay on the analogy and harmony of colours (1817) contains rich hand-colored wood-engravings with letterpress captions. Field was known as a chemist and for being especially skilled with pigments but fell short on being a color theorist after ignoring Isaac Newton’s ideas regarding color and light. Regardless, this book reveals his artistic sensibilities while expressing his theories on the relationship between the spectrum of colors and the scale of musical tones.

The Potentiality of Scores

By the twentieth century, music and sound recordings were readily available, which heightened the exceptionality and spectacle of the event or live performance. John Cage, a seminal influence on music, sound art, performance art, and more, was fascinated by the ability of music to make the listener more aware of their present. Cage argued any vibration of a particular moment could be considered music. While living in Europe as an art student he “noticed [on a street in Seville] the multiplicity of simultaneous visual and audible events all going together in one’s experience and producing enjoyment. It was the beginning of the theatre and circus.”

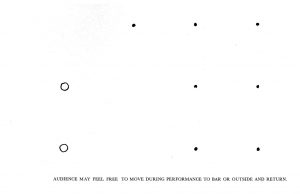

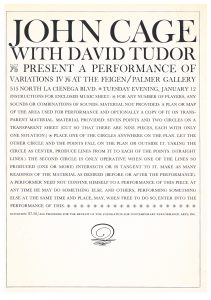

Variations IV by John Cage with David Tudor

Variations IV by John Cage with David Tudor

Variations IV (1965) is a work by Cage with composer David Tudor. It was presented at Cage’s first gallery concert, and is only remembered through printed instructions and a music sheet. The instructions read, “A performer need not confine himself to a performance of this piece. At any time he may do something else. And others, performing something else at the same time and place, may, when free to do so, enter into the performance of this.” Herbert Palmer, the owner of the gallery, recollected in a 2004 interview that Cage was in one room while Tudor was in another and between them were stacks of records and tapes.

Variations IV by John Cage with David Tudor

Variations IV by John Cage with David Tudor

He remembered that each would turn on different recordings and the music would change depending on where you were in the space. Palmer expressed, “It was so wild, with all the different kinds of music going at once.” More of Herbert Palmer’s interview is available at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Raven Chacon is an artist featured in Musical Thinking where a video work and original lithographs of four different scores are on display. The publication For Zitkála-Šá is a collection of this series of scores and the one selected in our exhibition is for his sister, Autumn Chacon. Similar to Cage’s musical sheet, there is a large location assumed or suggested. As a Diné and Xicana sound artist, activist, and community member, Autumn’s work examines contemporary methods of storytelling which dovetails into her work as a pirate radio engineer. In this score, Autumn is instructed to place, locate, and interact with lamps and radios while tracing her movements on the “score-map.” Every time the score is completed, a new path and story is forged and at the end she is invited to “sing the new song that [she] learned while performing the score.”

Musical score from María Magdalena Campos Pons and Neil Leonard’s “Identified.”

Musical score from María Magdalena Campos Pons and Neil Leonard’s “Identified.”

Soundscapes: Interpretations, Reverberations, and Process

In 2015, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery inaugurated its first performance art series, “Identify: Performance Art as Portraiture.” One of the performances, Identified by María Magdalena Campos Pons and Neil Leonard, was a study of President Abraham Lincoln, with the goal of reinserting the Black body into historical narratives evoking protest and devotion. The performance took place throughout the museum and its atrium. Portfolios containing 22 cards with texts, illustrations, and one musical score were handed to viewers. The score was performed by jazz musicians from Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Havana, a wind ensemble from the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, and folkloric musicians from Matanzas, Cuba. Together they reverberated the history that ties them together on the site of Lincoln’s second inaugural ball.

A promotional pamphlet for a monograph and two sound works, titled Finding Pictures in Search of Sounds (2008), depicts abstract fragments that question the interpretation of sound visually, aurally, and physically. The pamphlet by electronic musician and media artist, Stephen Vitiello, is a selection found in the AA/PG Library’s Art and Artist Files. The monograph contains individual booklets that act as visual clues to the sound pieces. Images of forests, reeds in water, and lines that mimic scores and wires can be vividly spread around a space without a distinct order and holds its own presence and experience. This pamphlet is just a shadow of the works it promotes, but reflects Vitiello’s practice of transforming unobserved atmospheric noises into engaging and imaginative soundscapes.

In 2021, ISSUE Project Room presented an online program of Annea Lockwood’s Piano Transplants with a Benefit event in her honor.

In 2021, ISSUE Project Room presented an online program of Annea Lockwood’s Piano Transplants with a Benefit event in her honor.

Womens Work (2019) is a facsimile of a publication from the mid-1970s. It was a magazine that highlighted the overlooked work of 25 female artists working with music, performance, and visual arts. Co-editor Annea Lockwood emphasized “We wanted to publish work which other people could pick up and do: that aspect of it was really important…this was not anecdotal, this was not archival material, it was live material. You look at a score, you do it.” One of the works in the book is by Lockwood herself and titled Piano Transplants (1968-1972). She cautioned that all pianos used for these performances should already be beyond repair, as she wrote and performed scores for the burning, drowning, and gardening of the instrument. She is particularly enamored with the environment, especially water, and collaborates and improvises with dancers, musicians, aquatic insects, and more.

George Brecht’s Water Yam (1963) was first published as a method to cheaply disseminate art democratically – widely and easily. Brecht was an important member of the experimental Fluxus art movement. The movement stressed the significance of the artistic process over the art product. The movement’s philosophy was grounded in experimental music and it was named after a magazine that featured artists and musicians who were influenced by John Cage. Water Yam is a box that contains many small, printed cards with instructions referred to as “event-scores.” Brecht became known for his haiku-like scores that left room for interpretation. Fourteen event-scores punctuate all three AA/PG Library display cases and were selected for their musical, performative, and tangential connections. These event-scores range from seemingly mundane tasks such as disassembling and assembling a flute, ambiguous encouragements of string quartets to shake hands, to supposedly more direct instructions to turn a radio on and then off at the first sound.

In the spirit of Musical Thinking, the library selections highlight visual works where music and sound – its memory, creation, and lived experience – is the primary focus. It also reveals how the visual arts has and continues to praise, document, and provide new pathways and interpretations of the fleeting medium. A particular event-score by Brecht feels like a fitting selection with which to conclude:

Event-score from George Brecht’s “Water Yam”.

Event-score from George Brecht’s “Water Yam”.

This exhibition and blog post were curated and written by Joana Stillwell, the Audiovisual Archivist at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive (MARMIA), who was the 2022 ARLIS/NA Wolfgang M. Freitag Internship Award recipient and was hosted at the Smithsonian American Art and Portrait Gallery Library. The exhibition will be on view from July-October, 2023, in the AA/PG Library.

Save Time in the Garden

Gardens provide us food, sustenance, exercise, and pleasure. Gardens also require a lot of work. It takes time, energy, and patience to grow a garden. In the early 20th century, gardeners hoping to save time and labor might have considered using this hand cultivator. It was described as a “Time Saving Garden Tool.”

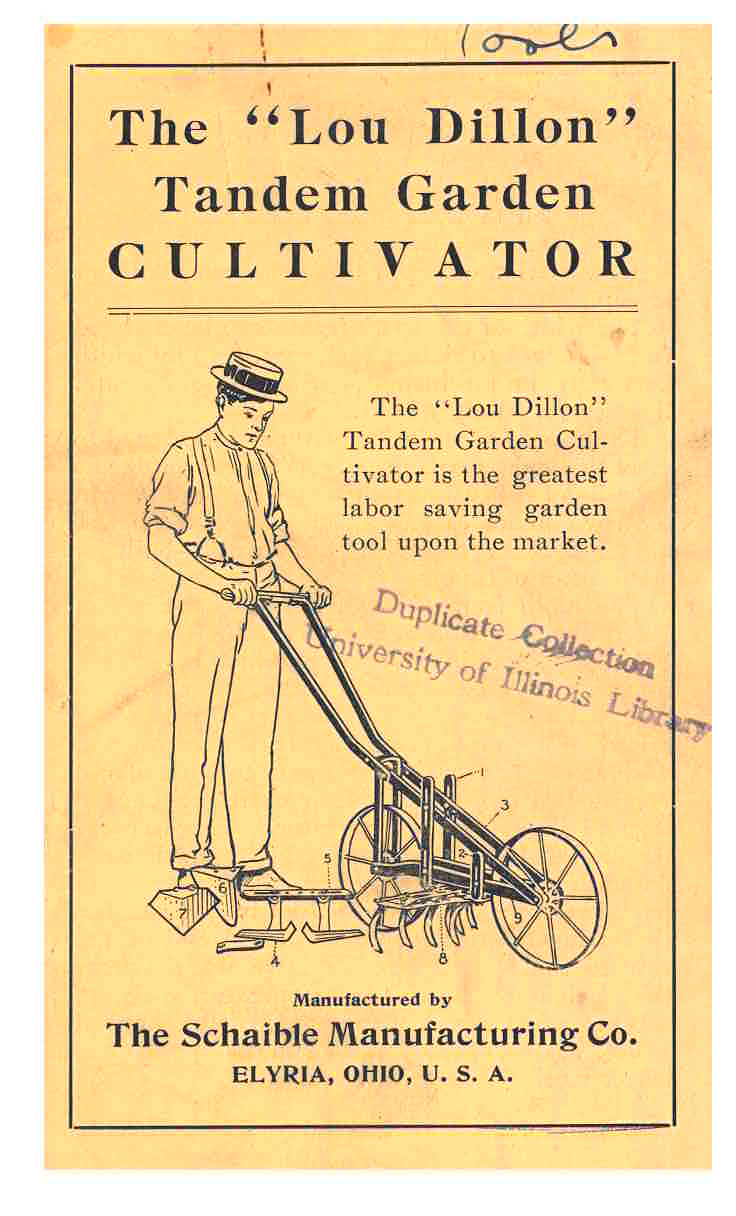

The trade catalog is titled “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905) by Schaible Mfg. Co. Even though it is only a few pages long, this small brochure is full of useful information. It provides instructions on how to use the cultivator, explains the benefits of using it, and illustrates specific parts, including tool attachments. It ends with customer testimonials.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), front cover/unnumbered page [1], gardener using the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.The “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator was constructed of steel and weighed 32 pounds. Gardeners had the option of buying tools to attach to the cultivator, such as the rake, sweep, or plow.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), front cover/unnumbered page [1], gardener using the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.The “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator was constructed of steel and weighed 32 pounds. Gardeners had the option of buying tools to attach to the cultivator, such as the rake, sweep, or plow.

Described as “simple to operate,” it allowed gardeners to walk each row of plants at “an easy, continuous” pace. Equipped with two wheels, the operator simply pushed it along instead of carrying the cultivator’s back end down each row.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered pages [2-3], Cut No. 2 showing gardener using the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.Throughout the brochure, the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator is described as adjustable. This was one feature that most likely appealed to many gardeners.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered pages [2-3], Cut No. 2 showing gardener using the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.Throughout the brochure, the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator is described as adjustable. This was one feature that most likely appealed to many gardeners.

The tooth frame of the cultivator consisted of seven steel teeth which were bolted to an adjustable frame. By using a thumb screw, the width of this tooth frame could be adjusted to any width between 8 and 16 inches. That adjustable frame was fastened to two yokes which could be raised or lowered. This gave gardeners the ability to choose a uniform depth at which to stir the soil.

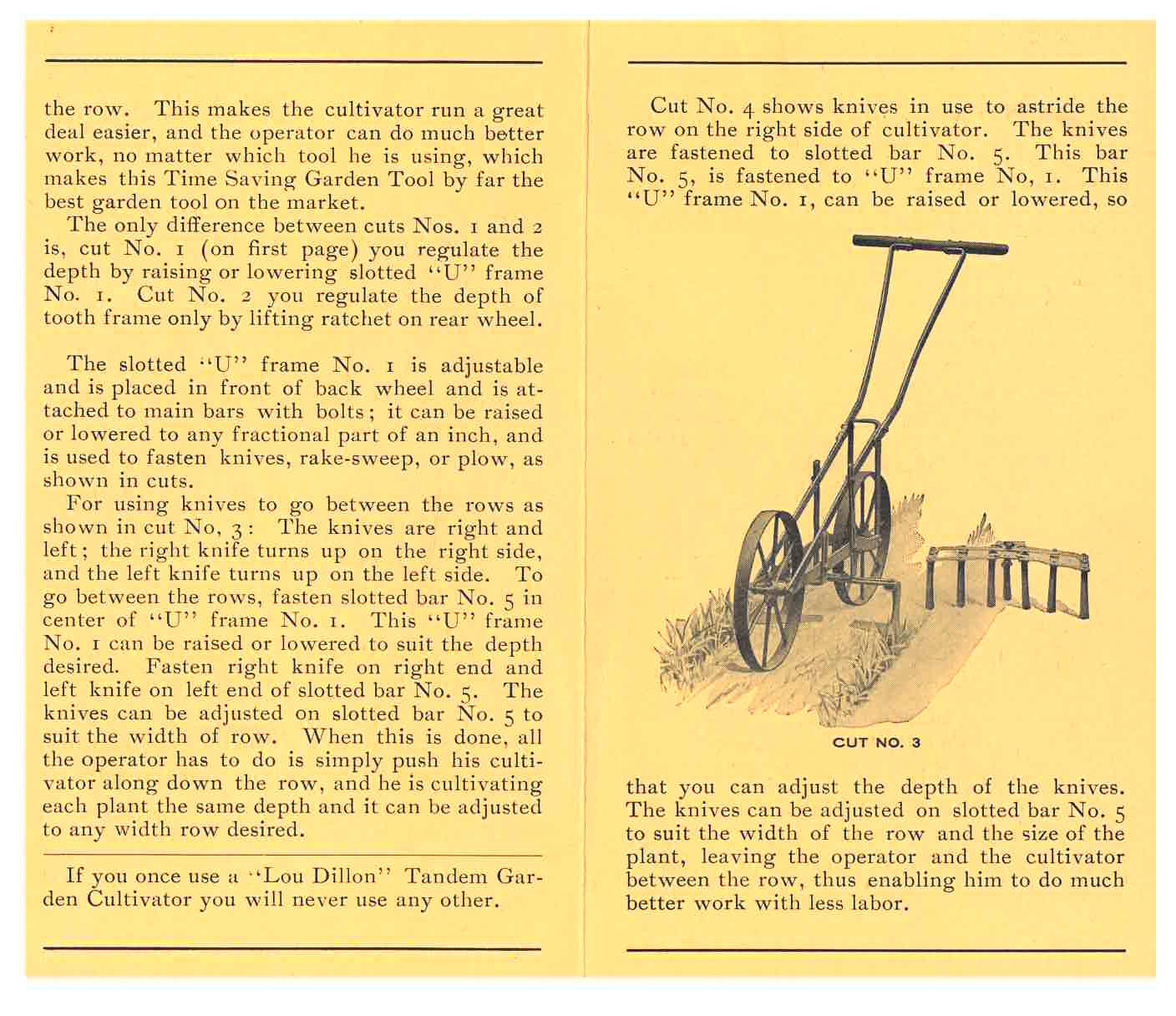

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered pages [4-5], Cut No. 3 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with knives.An adjustable slotted “U” frame was positioned in front of the back wheel and attached to the main bars with bolts. It was used to fasten tool attachments, such as knives, rake-sweep, or plow. A gardener could raise or lower the “U” frame to a fraction of an inch to work at a desired depth.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered pages [4-5], Cut No. 3 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with knives.An adjustable slotted “U” frame was positioned in front of the back wheel and attached to the main bars with bolts. It was used to fasten tool attachments, such as knives, rake-sweep, or plow. A gardener could raise or lower the “U” frame to a fraction of an inch to work at a desired depth.

Cut No. 3 (above) and Cut No. 4 (below) illustrate the use of knives fastened to the cultivator. These knives could be adjusted to fit a specific width for a row or size of plant.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [6], Cut No. 4 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with knives attached.The rake attachment was positioned in front of the “U” frame with two bolt hooks and fastened with burs. Again, the depth of the rake was adjustable by raising or lowering the “U” frame. Depending on the soil, the rake could be used in a vertical position or at a slant.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [6], Cut No. 4 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with knives attached.The rake attachment was positioned in front of the “U” frame with two bolt hooks and fastened with burs. Again, the depth of the rake was adjustable by raising or lowering the “U” frame. Depending on the soil, the rake could be used in a vertical position or at a slant.

Another attachment was the sweep, shown below in Cut No. 5. It was fastened underneath the “U” frame and could be adjusted to any depth from a fraction of an inch to four inches.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [7], Cut No. 5 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with sweep attached.The catalog ends with two customer testimonials sharing positive reactions to this cultivator. Anthony Fite of Hurtsville, Albany Co., NY mentions that he received the cultivator, “…and will say it is very satisfactory. I have used it with much success in onions, beets, celery, parsnips and carrots. Would advise all market gardeners to buy one.”

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [7], Cut No. 5 showing the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator with sweep attached.The catalog ends with two customer testimonials sharing positive reactions to this cultivator. Anthony Fite of Hurtsville, Albany Co., NY mentions that he received the cultivator, “…and will say it is very satisfactory. I have used it with much success in onions, beets, celery, parsnips and carrots. Would advise all market gardeners to buy one.”

W. J. Murphy of Elmira, NY, wrote on October 6, 1905, commenting: “…I don’t see how I ever got along without it before, as I have a large garden and a big patch of strawberries to take care of, and I can do the work on them in fifteen minutes what it used to take me three hours to do. I am just stuck on it.”

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [8], customer testimonial and benefits of the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.“Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905) by Schaible Mfg. Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Schaible Mfg. Co., Elyria, OH. “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905), unnumbered page [8], customer testimonial and benefits of the “Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator.“Lou Dillon” Tandem Garden Cultivator (circa 1905) by Schaible Mfg. Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Meet Author, Suffragist, and Minister Phebe Hanaford