Smithsonian

Library Descriptive Data Unleashed in SVDE: Making Data More Meaningful

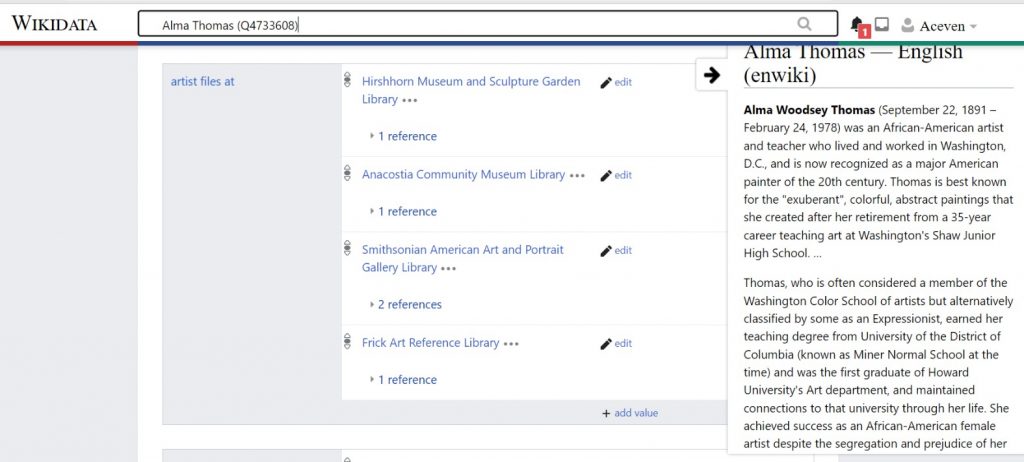

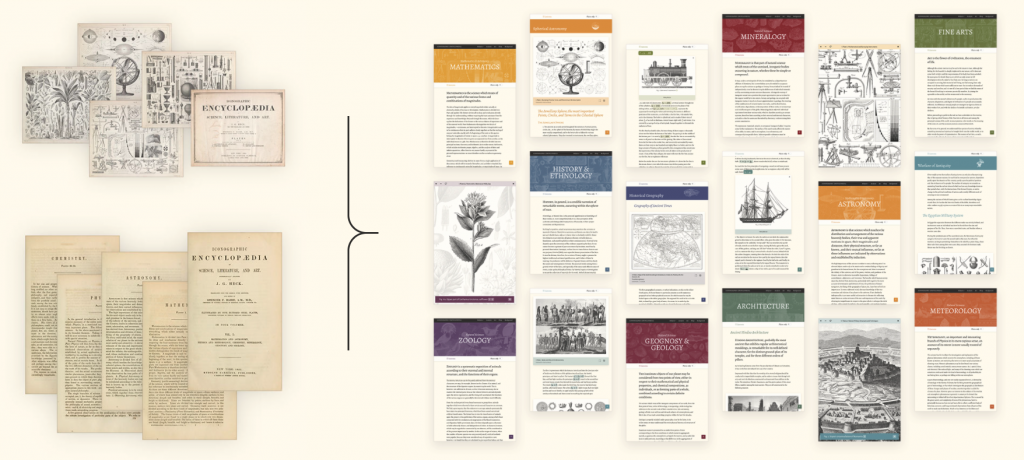

Previously, we have shared one stream of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ linked data experiments, Wikidata, which is based on a Wiki platform. In this post, we share another linked data experiment that focuses on the traditional bibliographic data (the library catalog) transformation with the Shared Virtual Discovery Environment (SVDE) BIBFRAME project.

Linked open data is often considered synonymous with the semantic web, where structured data interconnects with structured data web query tools (such as SPARQL). Then, the data or information can be represented in different visualizations —data graphs, charts, bars, maps, timelines, etc. Cultural heritage organizations such as the Smithsonian Institution, and specifically the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, have been working diligently to adapt their internal data to meet In an effort to reap the benefits of linked open data, we’ve moved towards complete conversion of our existing library catalog data to this format, and come away with an exciting initial result.

The international library community has been setting policies and encouraging best practices to accommodate bibliographic description, moving away from self-contained “document style” records, to providing descriptive data in which statements about a resource (an object, a thing) are assembled more flexibly. How data gets assembled and reassembled will be based on user preferences and needs. New connections can easily be made among resources. Author A published Title A. Title A has Illustrator A. Illustrator A published Title B. etc., etc.

The international Shared Virtual Discovery Environment (SVDE) project gave the Libraries and Archives the opportunity to model our library catalog records to realize these goals. The entity-relationship description, and the hallmark of this data model, is data accompanied with URIs (an identifier following a HTTP prefix). In this post, we will share the journey of how the SVDE platform aligned Smithsonian Libraries and Archives catalog records in compliance with structured data standards, allowing them to be exposed directly onto the open web.

Enriching Horizon Bibliographic Data

The Libraries and Archives’ current bibliographic data hosting service is Horizon, an older integrated library system no longer supported by research and development. Its system infrastructures are barely keeping in step with the library’s basic operations. Its ability to handle innovative approaches to data representation and visualization are no longer adequate. Because of this, our library data lacks the ability to connect natively with external sources. Library staff have been investigating its replacement for several years.

Realizing that the academic, research, and national library community are moving toward a linked open data environment for library data, a group of Libraries and Archives staff embarked on a series of linked data modeling experiments. Encouraged by progress from other libraries, the Smithsonian team began projects to enhance and transform the library’s catalog of bibliographic data to the BIBFRAME model beginning in 2019.

The task at hand was to expand names (corporate bodies, persons, families) and LCSH (Library of Congress Subject Headings) to a form that facilitates the use of identifiers, in addition to publishing library data on the web. Then, incorporating FAST Headings (Faceted Application of Subject Terminology) to enable grouping of topics, chronology, geographic names, etc. These preparatory activities paved the way for the library’s linked open data journey. Months into the project, a small number of catalog records received minimal enhanced treatment, approximately ten thousand titles over a two-year period. With the support of an internal fund, the library’s bibliographic linked open data project was scaled up to nearly 2 million records. Library data were moved out of siloes and exposed to the open web with help from the SVDE initiative. This allowed us to leverage the technology and expert knowledge of the well-established SVDE team along with scores of member libraries’ collections and structured data expertise to move the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives toward interoperability. This helps us achieve the strategic goals set forth by Secretary Lonnie Bunch.

Share-VDE (SVDE) Initiative

In 2016, the research and development team of Casalini Libri, an international bibliographic and authority data provider, the @Cult, a provider for library systems, Stanford University Library, and a group of academic, research and national libraries from North America and Europe worked to realize a linked open data vision. The resulting SVDE is a library-driven initiative to create “the cleanest, most reconciled pool of collective data shared across collections” and to shape the future of bibliographic linked open data developments.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ bibliographic and authority records were “dropped off” for SVDE teams to transform to a linked open data format using the standard BIBFRAME 2.0. This included extracting heading strings to resolve identifiers in a web format (prefix with HTTP), then conducting live queries via SVDE API tools on open access resources. This journey through the 24 processes for library bibliographic data successfully moved document-type records to entity-relationship data structure. This achieves the promises of the SVDE initiative to increase library collections discoverability by enriching library data with URIs, allowing wider and more direct interactions with linked data in the SVDE cluster knowledge database (known as Sapientia), and to keep pace with semantic web applications and developments.

The previous improvements to library bibliographic data done by Smithsonian Libraries and Archives staff were greatly enhanced by the SVDE project. Over a two-year period, staff were only able to add linked open data processes to a little over ten thousand bibliographic records. The SVDE team completed close to 2 million bibliographic records in a short period of time. In addition, our library data is now in the SVDE Entity Discovery Portal and Linked Data Management System

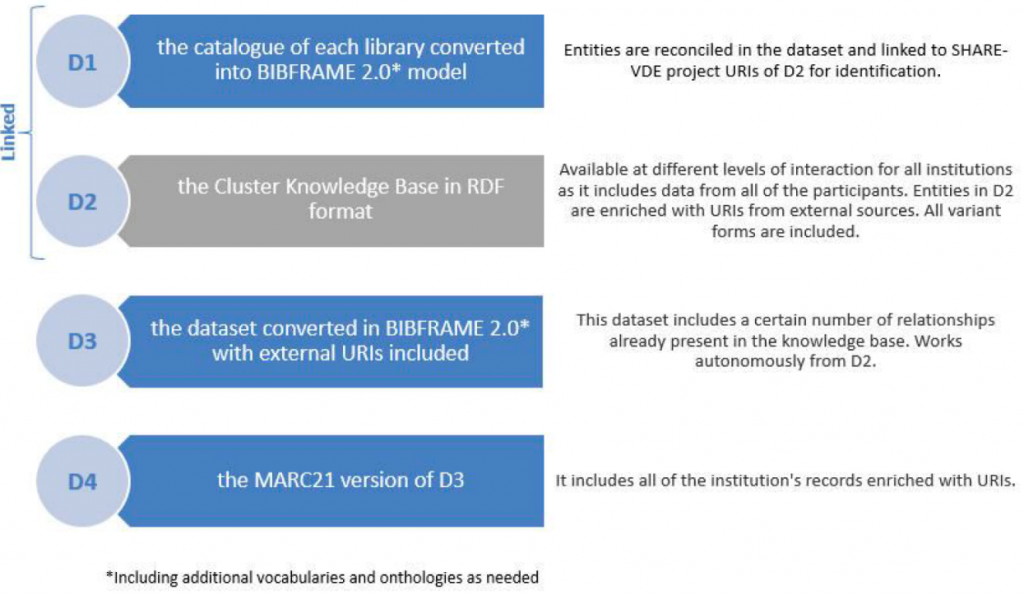

Four deliverables for participating libraries, from presentation at Library of Congress’ Digital Future and You (2018)

Four deliverables for participating libraries, from presentation at Library of Congress’ Digital Future and You (2018)

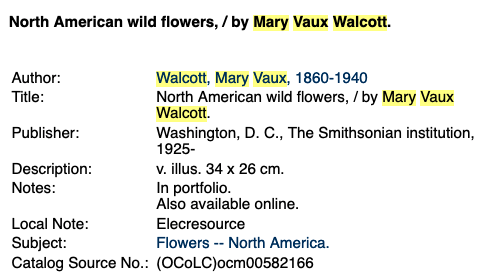

So, what do we mean when we say transitioning document-type catalog records to entity-relationship structured data? Let’s look at an example, the celebrated work, North American wild flowers, by Mary Vaux Walcott, wife of our fourth Secretary, Charles Doolittle Walcott.

SIRIS (Smithsonian Institution Research Information System) catalog record for North American Wild Flowers.

SIRIS (Smithsonian Institution Research Information System) catalog record for North American Wild Flowers.

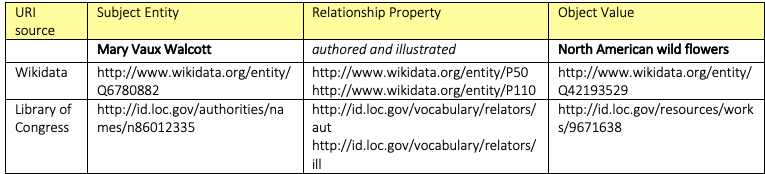

Descriptive statements of entity relationships parse each field to separate components. When a name (for a person, geographic, topics, etc.) URI is available, SVDE will link the text string to its corresponding URI, as seen in the table below.

Entity-Relationship data model

Entity-Relationship data model

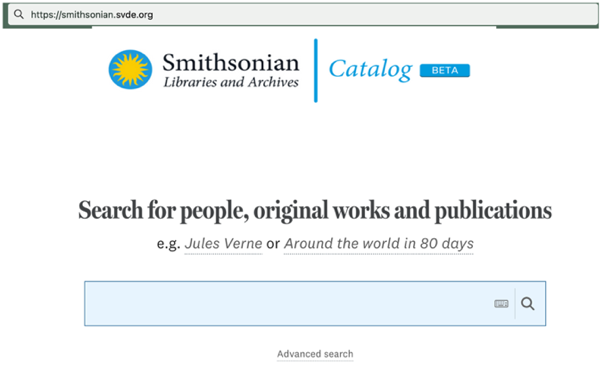

The SVE Entity Discovery Portal interface (UI) offers users a clean front-end design for simple and advanced search options with seamless viewing of the entity pages embedded links, including data from external services (such as images from Wikimedia Commons, description from Wikidata, articles from Wikipedia, and others). Pages include language preference for navigation.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Catalog BETA: https://smithsonian.svde.org

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Catalog BETA: https://smithsonian.svde.org

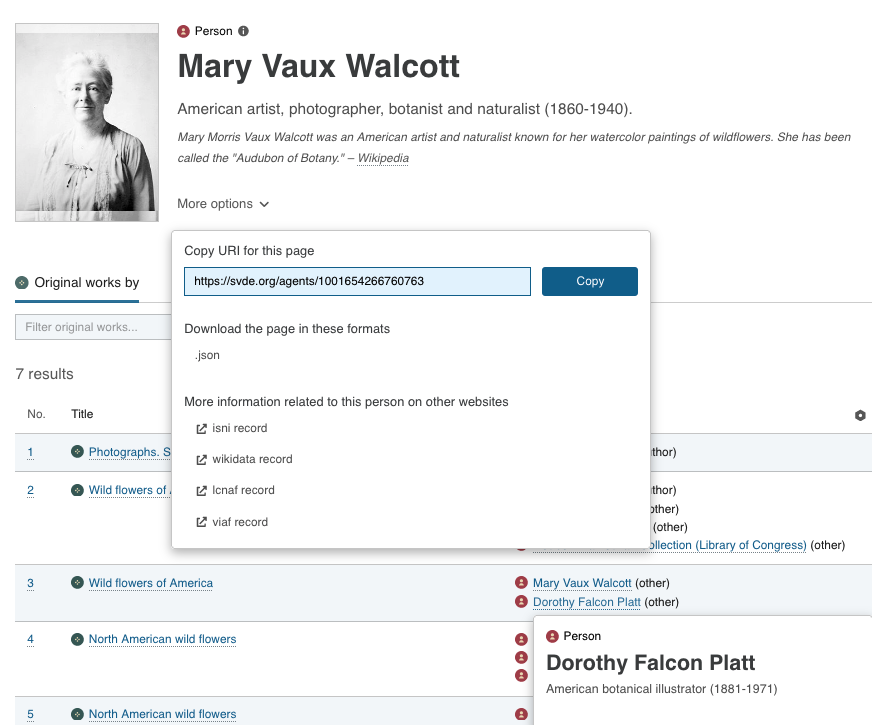

When comparing the search “Mary Vaux Walcott”: the library’s current catalog presents a document-style description that lacks interactivity to external resources. While in the SVDE Entity Discovery Portal, you will notice the entity-relationship based data model embedded external information from Wiki services. Wikidata description and Wikipedia article describing author, Mary Vaux Walcott, comprised as part of the search output seamlessly. Additional links to external sources, like identification of an entity, contributor, publisher, etc., are clearly represented.

Person search: “Mary Vaux Walcott”, links to external resources, including available data format for download

Person search: “Mary Vaux Walcott”, links to external resources, including available data format for download

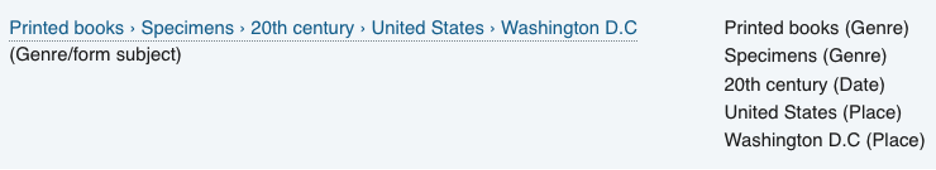

The related subject links for the book North American wild flowers cover diverse types, including genre/form of the publication. Opening up the Library of Congress Subject Headings creates greater opportunity for users to connect to other similar types of material or topics.

Library of Congress Subject Heading is decomposed to genre, date, and place

Library of Congress Subject Heading is decomposed to genre, date, and place

To continue data quality and assurance, SVDE is designing an entity editor for library staff to manage and curate information. SVDE’s back-end technology prepared the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives data for indexing, clustering, searching and representation. Their work helps data providers like the Smithsonian reap the benefits of linked data and connect library collections on the web in a user-friendly and informative manner.

In the next few months, Libraries and Archives expects to receive the enhanced bibliographic records with URIs in our traditional MARC format, as well as the transformed format in BIBFRAME RDF. We will have opportunities to further investigate how the new data formats can help realize the potential of descriptive data for visualization, in fulfilling our goals, and in connecting library collections with users and data consumers. We are edging forward excitedly in the semantic world for publishing and research.

Further Reading:

- Linked open data, what is it?

- Library of Congress BIBFRAME

- Share VDE (Virtual Discovery Environment) Initiative Wiki page

- Share-VDE Presentation at the Library of Congress’ Digital Future and You (2018):

“Highlights of the NMAAHC Library Collection” Opens at National Museum of African American History and Culture

This September, the National Museum of African American History and Culture celebrates its sixth anniversary. When it first opened, our National Museum of African American History and Culture Library, housed on the second floor, displayed a noteworthy selection of highlights from its collection. The library has just unveiled a new exhibit featuring another set of books and materials significant to the African American story. Items in Highlights of the NMAAHC Library Collection span over a hundred years and a variety of formats – from an 1886 biography of Harriet Tubman to a 2009 artists’ book celebrating the inauguration of President Barack Obama.

Cover and title page of Harriet, The Moses of Her People (1886).

Cover and title page of Harriet, The Moses of Her People (1886).

Shauna Collier, head of the library and curator of the exhibit, was inspired to pull together this particular set of collection items partly by the pandemic. During online presentations and virtual trainings, these were some of the materials she found herself referencing most, and ones she particularly missed sharing with researchers in person. They may not fit neatly into a theme, but each has an important story to tell. Collier also wanted to highlight the contributions of donors to the library. Ten of the eleven featured items were donated to the collection. For example, Oscar Micheaux’s The Story of Dorothy Stanfield (1946) was the gift of film historian and director Pearl Bowser. The Mind of the Negro (1926) by Carter Woodson was a gift from Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch when he was the museum’s inaugural director.

The Story of Dorothy Stanfield (1946)

The Story of Dorothy Stanfield (1946)

Each work on display is important in its own unique way. The Anthology of Rap (2010) highlights a vibrant contemporary subject and evolving area of study. Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life (1858) directly influenced Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin—the Uncle Tom character in her book was based on Josiah Henson’s life. Oscar Micheaux’s 1920 film Within Our Gates is one of many collected to support our research community. It is a powerful response to The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith’s 1915 racist film about the Civil War.

An exciting feature of the exhibit is the incorporation of the Hi App, an innovative gallery guide that encourages in-person visitors to use their mobile devices to connect with additional online content. While browsing the library selections, visitors can also explore blog posts, museum objects, and digitized books to broaden their experience.

Shauna Collier with the exhibit she curated, Highlights of the NMAAHC Library Collection.

Shauna Collier with the exhibit she curated, Highlights of the NMAAHC Library Collection.

Highlights of the NMAAHC Library Collection will be on display on the second floor of the National Museum of African American History and Culture until April of 2023.

Meet Artist Atlanta Constance Sampson and Her Lifelong “Obsession”

This post was contributed by Isabella Buzynski, 2022 Summer Scholars intern with the American Art and Portrait Gallery (AA/PG) Library. Isabella is currently attending the University of Michigan School of Information for the Master of Science in Information program.

This summer, I had the great pleasure of interning under the mentorship of Alexandra Reigle at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library. I have continued an ongoing project to process and integrate the Art Students League of New York papers into the library’s existing Art and Artist File collection, comprising over 150,000 files of ephemeral materials on art, artists, art institutions, collectors, and special subjects. Day-to-day, this consists of pulling batches of Artist Files, deciding what items should be added to each, removing dozens of staples, stamping the items, making a mess, and then putting them all back on the shelf for researchers to consult. I have learned first-hand how the decisions that archivists and librarians make shape the historical record and have gained an expedited education in American art through the exhibition materials, news articles, and letters that I encounter. I also encountered some incredible stories, including that of Atlanta C. Sampson’s ninety-year career as an artist.

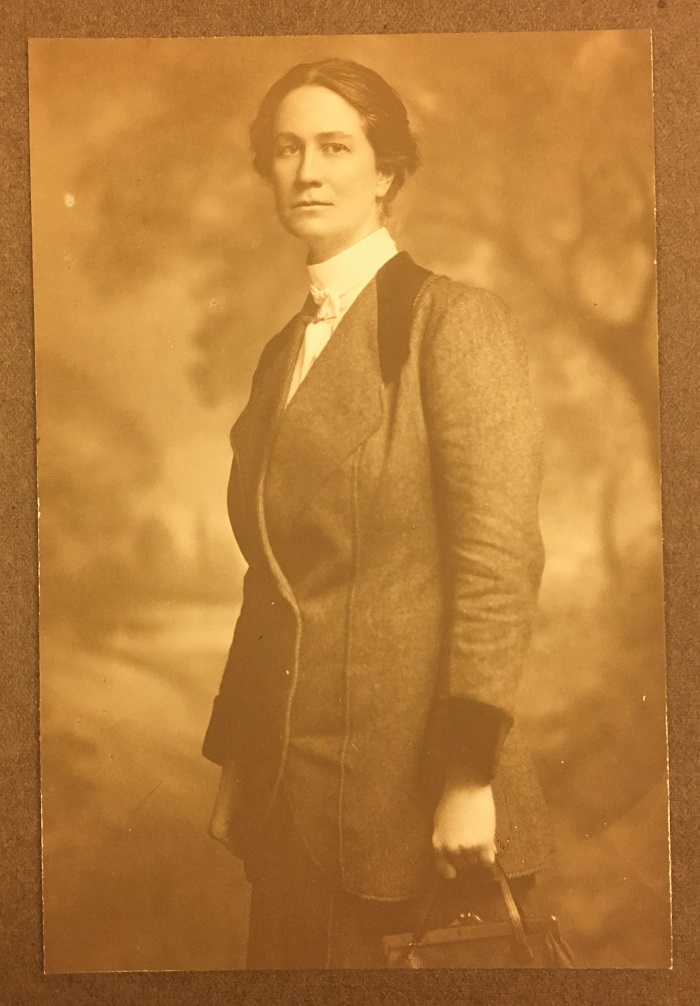

Born in 1896 on a small farm between Lyle, Minnesota, and Toeterville, Iowa, Sampson painted for most of her long life in relative obscurity. She was “discovered” in 1987 when Owen Ryan, a marketing executive, came across one of her paintings in the window of a New York delicatessen. Ryan was introduced to Sampson, sitting inside at one of the booths, and eventually took her up on an invitation to see the hundreds of paintings that filled her tiny one-room apartment on the Lower East Side to the brim. He was dazzled by the beauty of her work and touched by the determination of the 91-year-old-woman who had labored uncomplainingly through decades of want in pursuit of her passion. “God created me to be an artist,” she told Ryan, “It was just as necessary as eating or sleeping for me to paint. I had to do it. It was an obsession all my life.” At that time, thirty years after moving to New York City to become a full-time artist, Sampson was preparing to move back to Toeterville having never realized her dream of putting on a one woman show. Ryan decided to champion her cause, organizing her first solo show at the National Arts Club in Manhattan.

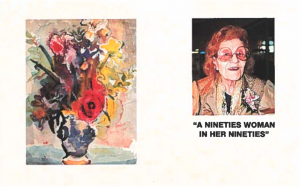

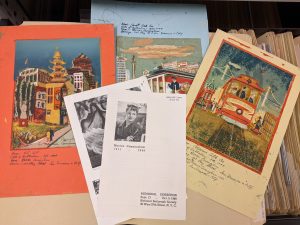

A postcard from the Unionhurst Gallery in Toeterville, Iowa, which was established by Sampson’s nephew, Frank Langrock. The front features an image of Atlanta Sampson wearing big pink glasses and is captioned “A Nineties Woman in Her Nineties.” The back of the postcard includes a color reproduction of one of Sampson’s watercolors depicting a bouquet of flowers. The inside of the postcard reads: “Original Paintings by Atlanta Constance Sampson, Box 144, Toeterville, Iowa 50481. ‘A Nineties Woman in Her Nineties.’ Mediums include: Watercolor, Ink and Pencil, Chalk, Abstract Oils. Over eight decades of Art Production.”

A postcard from the Unionhurst Gallery in Toeterville, Iowa, which was established by Sampson’s nephew, Frank Langrock. The front features an image of Atlanta Sampson wearing big pink glasses and is captioned “A Nineties Woman in Her Nineties.” The back of the postcard includes a color reproduction of one of Sampson’s watercolors depicting a bouquet of flowers. The inside of the postcard reads: “Original Paintings by Atlanta Constance Sampson, Box 144, Toeterville, Iowa 50481. ‘A Nineties Woman in Her Nineties.’ Mediums include: Watercolor, Ink and Pencil, Chalk, Abstract Oils. Over eight decades of Art Production.”

“True Colors: The Paintings of Atlanta Constance Sampson, 1896 – Present” opened on May 24, 1988, and was an immediate success. It elicited excellent reviews from respected art critics and interviews with CBS, CNN, and NBC. In the years between her first solo show and her death at the age of 98, Sampson’s work was exhibited in various U.S. museums, auctioned at Christie’s, and installed in a permanent collection at Unionhurst Gallery in Toeterville. On her 96th birthday, she was honored for her contribution to the arts with a private reception and exhibition at the Russell Building Rotunda on Capitol Hill. Newspapers invariably referred to her story, one of exceptional struggle and satisfying payoff, as an art-world “fairytale.” But when I read through the Atlanta C. Sampson file, I was less intrigued by her seven years of relative fame than by her nine decades of tireless work. It seems there was never a moment when she wasn’t absorbed with her art.

An invitation to the reception and private viewing of Atlanta Sampson’s works held in The Mansfield Room at The Capitol on September 30, 1992. The accompanying exhibition was held in the Rotunda of The Russell Senate Office Building from September 30-October 2, 1992 and was sponsored by Senators Charles Grassley, David Durenberger, Paul Wellstone, Donald W. Riegle, Jr., Carl Levin, Paul Simon, Alan Dixon, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Tom Harkin.

An invitation to the reception and private viewing of Atlanta Sampson’s works held in The Mansfield Room at The Capitol on September 30, 1992. The accompanying exhibition was held in the Rotunda of The Russell Senate Office Building from September 30-October 2, 1992 and was sponsored by Senators Charles Grassley, David Durenberger, Paul Wellstone, Donald W. Riegle, Jr., Carl Levin, Paul Simon, Alan Dixon, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Tom Harkin.

After graduating from the University of Minnesota Art Education Department in 1918, Sampson moved to Detroit where she worked as an art teacher during the day and spent her evenings taking art classes. During the 1930s and 1940s, she exhibited frequently in regional exhibits held at the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Scarab Club, among other smaller art galleries. She entered her watercolors in competitions against other instructors from the Wayne University art department and Detroit Public Schools, winning second and third prizes. Her paintings were occasionally reproduced by the Detroit News and Free Press. During this time, in addition to her earlier still lifes of flowers and landscapes, Sampson began depicting urban scenes of Detroit’s industrial worksites, jazz clubs, and markets. She experimented with watercolor techniques and abstraction.

Sampson’s “Market Scene” was reproduced in the Detroit Free Press as “one of the strongest paintings” shown at the fifth annual exhibition by art instructors of the Detroit Public Schools, which was held at the Scarab Club from October through November 8th, 1940. Sampson is listed as a substitute teacher, which likely allowed her more time for painting than full-time teaching. Source: The Detroit Free Press, October 20, 1940, p. 55.

Sampson’s “Market Scene” was reproduced in the Detroit Free Press as “one of the strongest paintings” shown at the fifth annual exhibition by art instructors of the Detroit Public Schools, which was held at the Scarab Club from October through November 8th, 1940. Sampson is listed as a substitute teacher, which likely allowed her more time for painting than full-time teaching. Source: The Detroit Free Press, October 20, 1940, p. 55.

By 1946, Sampson was exhibiting and selling her watercolors regularly at the Detroit Artists Market and began exhibiting her work with the Detroit Watercolor Society, which was founded that same year. During a time when women were often excluded from male-dominated arts and social clubs, she was an active member of the Detroit Society of Women Painters and Sculptors and on at least one occasion exhibited at Women’s City Club, which was at that time one of the largest women’s clubs in the world. From 1948 through 1952, Sampson exhibited and won prizes at the Chicago International Watercolor Competition.

Despite these successes, by the late 1940s Sampson was becoming restless, feeling that she did not have enough time to devote to her art while also working as a teacher. She decided to retire from teaching and, sometime around 1954 (sources vary along with Sampson’s memory), she arrived in New York City to become a full-time starving artist at the age of 56. She knew no one in the city, and supported herself through office work supplemented by occasional freelance gigs designing fabric and wallpaper prints. She studied in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and in New York City under the famous artist Hans Hofmann, who encouraged her to continue painting and honing her craft. Taking this advice, in the 1960s she enrolled in classes at the Art Students League of New York, studying with Professors Dorfman, Stamos, Thomas, Fogarty, and Klonis. Likely influenced by these professors and her exposure to the thriving abstract expressionism movement in New York City, Sampson began experimenting with colorful abstract compositions. One of these works, “Light Fantasy with Red,” was later selected to become part of the permanent collection at the Art Students League.

Although Sampson’s work was modern, she was often turned away from galleries because of her age. A woman in her 70s, she could not compete against les enfants terribles, young artists like Robert Rauschenberg who were charming the art world with their youth and irreverence. She sold few of her paintings and, unable to afford tuition, was forced to take a hiatus from her studies. Sampson lied about her age to get typing jobs to pay for art materials and when the funds ran out she painted on paper bags and the backsides of used canvases. Continuing to work part-time to sustain herself, she returned to the Art Students League in the late 1970s. In 1981 and again in 1982, she won Merit Scholarships at the League that allowed her to paint full-time for two years. I imagine this was an exciting time for Sampson, always yearning for more time to devote to her “obsession.”

Sampson’s watercolor of cranes was discovered by Owen Ryan in 1987 and the rest, as they say, is history. Her story and her paintings, now scattered across the country in public and private collections, are her legacy—there’s even a lovely song dedicated to Atlanta C. Sampson. After all, I am struck by how little we can ever know about her, by how much is absent from the Artist File. That said, I hope her story moves you like it moved me. As I say goodbye (for now!) to the AA/PG LIbrary to finish my degree and continue pursuing a career in archives, I am inspired by Sampson to never wait around for miracles, but to create opportunities to always do what I love.

Sources:

Atlanta C. Sampson, Art & Artist Files, Smithsonian American Art and Portrait Gallery Library, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, Washington, D.C.

The Detroit News:

- “Variety of Talent Marks Women Painters Show,” March 17, 1935, Arts Section, 17.

- Florence Davies, “Michigan Artists’ Show Opens With Boom in Sales,” November 12, 1935, 9.

- “Wayne Art Awards Announced at Show,” May 22, 1938, General News, 16.

- “Water Color in Michigan Show,” December 7, 1941, Sports Section, 13.

- Florence Davies, “Full Program Ahead,” May 19, 1946, Home and Society, 19.

- Florence Davies, “Tenth Annual at Wayne,” May 26, 1946, Home and Society, 19.

- Florence Davies, “Art Lovers Hail Market,” October 13, 1946, Home and Society, 21.

- “Women Painters Plan Exhibition,” April 3, 1947, 34.

- Florence Davies, “Michigan Water Colors,” June 29, 1947, Home and Society, 17.

- Joy Hakanson, “A Full Art Calendar,” January 11, 1948, Home and Society, 17.

- Joy Hakanson, “Thinking Caps in Order,” February 15, 1948, Home and Society, 22.

- Joy Hakanson, “Design for Building,” April 18, 1948, Home and Society, 22.

- “Art Notes,” March 27, 1949, Home and Society, 18.

- Joy Hakanson, “Detroit Masterpieces,” April 24, 1949, Home and Society, 22.

- Joy Hakanson, “Quartet Shares Artists Market Show,” January 22, 1950, Home and Society, 16.

- “Women’s Annual,” April 16, 1950, Home and Society, 22.

The Detroit Free Press:

- “State Art Show Starts Tonight,” November 12, 1935, 8.

- “Art Educators Exhibit,” October 20, 1940, 55.

- “Teachers Take Turn as Art Exhibitors,” October 5, 1941, 55.

- “Show Discloses Arresting Talent,” October 4, 1942, 57.

- “Artists’ Market Show,” May 19, 1946, 18.

- May 26, 1946, 18.

- Arthur Dorazio, “Art Notes,” September 30, 1951, 22.

The Iowa Courier:

- Jennifer Jacobs, “Artist remains in spotlight at age 98,” September 19, 1994.

The New York Times:

- Gregory Jaynes, “An Artist at 91: Her First Show Outside the Deli,” April 20, 1988, B1.

- Michael T. Kaufman, “Amazement, Wonder and Meaning of Beauty,” November 18, 1992, B4.

- William Grimes, “Atlanta C. Sampson, Artist 98; Had Her First Solo Show at 91,” May 24, 1995, D19.

Introducing “Smithson to Smithsonian”

Today, on the Smithsonian’s birthday, we are pleased to celebrate the launch of a new, refreshed, and greatly expanded web exhibition, Smithson to Smithsonian.

Explore Smithson to Smithsonian today!

The Smithsonian looked a little different when it celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1996. Then, there were only 16 museums (now there’re 21), and the Smithsonian had just launched its first website. Like so many other cultural heritage organizations, the Smithsonian Institution Archives was new to the digital age. Still, staff dove headfirst into the world of online exhibitions with From Smithson to Smithsonian: The Birth of an Institution. A collaboration between the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, the Smithsonian Institution Archives, and the Architectural History and Historic Preservation Division, the online exhibition traced the life of Smithsonian founding donor James Smithson, his bequest to the United States, and the Institution’s founding. You can still view it today in all of its pixelated, ‘90s glory.

Introduction page of the online exhibition From Smithson to Smithsonian (1996).

Introduction page of the online exhibition From Smithson to Smithsonian (1996).

Over the last 25 years, we have learned a lot more about our mysterious founder. In 2007, historian Heather Ewing, the lead researcher and writer of this new exhibition, published The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. Based on years of research in archives across Europe and the United States, it reconstructed Smithson’s life through the diaries and correspondence of his network of scientific colleagues, friends, and family. In 2020, retired curator Steven Turner illuminated Smithson’s accomplishments in chemistry and mineralogy, taking us inside an 18th-century laboratory with his book, The Science of James Smithson: Discoveries from the Smithsonian Founder. And most recently, Archives conservator William Bennett took a deep dive into the Hungerford Deed through a new web exhibition, which builds on Ewing’s work to shed light on Smithson’s motivations for donating his fortune to a country he had never even visited.

During this time Libraries and Archives staff has also worked to make Smithsonian history more accessible—from curating online exhibitions and writing blog posts to making records more discoverable to researchers.

The new iteration of Smithson to Smithsonian highlights this new research. The first three sections explore James Smithson’s early life, scientific contributions, and his bequest to found the Smithsonian. You can watch a demonstration of an 18th-century blowpipe, see the booklet Smithson used to write his extraordinary will, and learn about the origins of Smithson’s money—the 104,960 gold sovereign coins that started the Smithsonian.

The next four sections trace Smithsonian history over the decades, featuring people, objects, and major events from its founding in 1846 until 2022. Did you know the National Weather Service started as a Smithsonian project? Or that the Smithsonian initially turned down the offer of the first airplane, the Wright Flyer? And had you heard that a great fire at the Smithsonian Castle destroyed Smithson’s personal effects? Dive in to discover these stories and so much more.

Where the final two sections of the 1996 exhibition focused on the legacies of the Institution’s first two Secretaries, this new web exhibition guides visitors through Smithsonian history by featuring lesser-known groundbreakers, like Barry Hampton, a Black mail clerk who confronted discrimination and earned the role of curatorial aide, and Mary Jane Rathbun, the first woman to serve as a full-time curator at the Museum.

Today, scientists, artists, historians, and community members use the Smithsonian’s collections in so many incredible ways. Who knows what the next 25 years will bring? As we look ahead, we reflect on Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III’s words on the significance of understanding our institutional history.

Only by recognizing the ways in which this Institution and its leaders both lived up to and fell short of their own standards can we become the Smithsonian of Henry’s and Ripley’s highest aspirations: a place of accessibility, of innovation, of relevance, of richness and meaning. As we reflect on 175 years of history, our great strength is our willingness to engage fully with our past, build on our achievements and evolve to meet the lofty goals we have always set for ourselves.

Join us on August 31 at 5 PM ET for a discussion with Smithsonian staff who are working to restore, highlight, and amplify cultural heritage from historically marginalized communities. This program is the second in a series related to launch of Smithson to Smithsonian. The first program, a presentation and discussion about the legacy of James Smithson with Ewing, Turner, and librarian Leslie Overstreet, is now available on our YouTube channel.

Join us on August 31 at 5 PM ET for our next program, Smithson to Smithsonian: Expanding Our Story

Join us on August 31 at 5 PM ET for our next program, Smithson to Smithsonian: Expanding Our Story

Explore Smithson to Smithsonian today!

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is especially grateful to the Smithsonian at 175 committee for their generous support of this web exhibition.

Related Resources

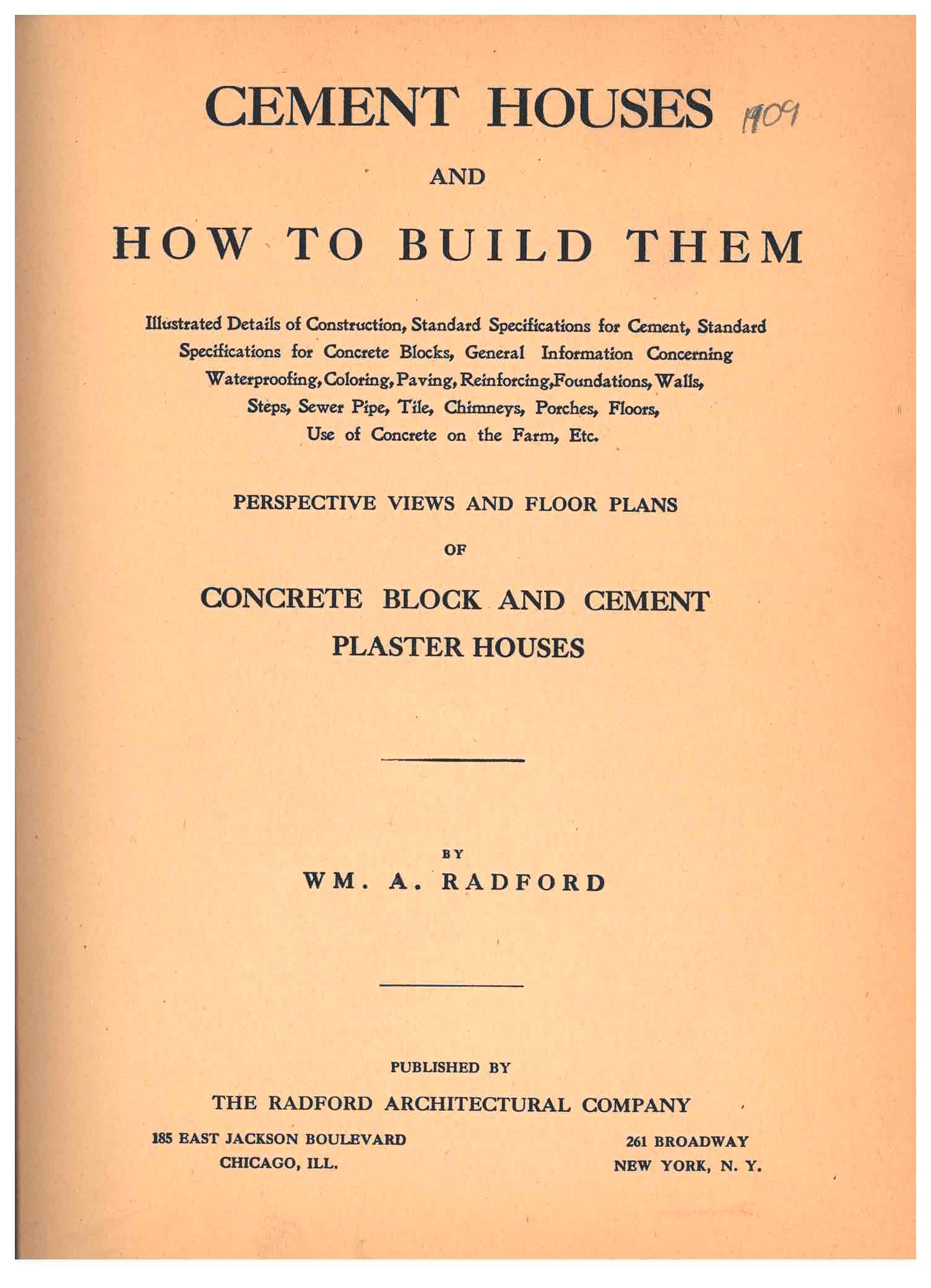

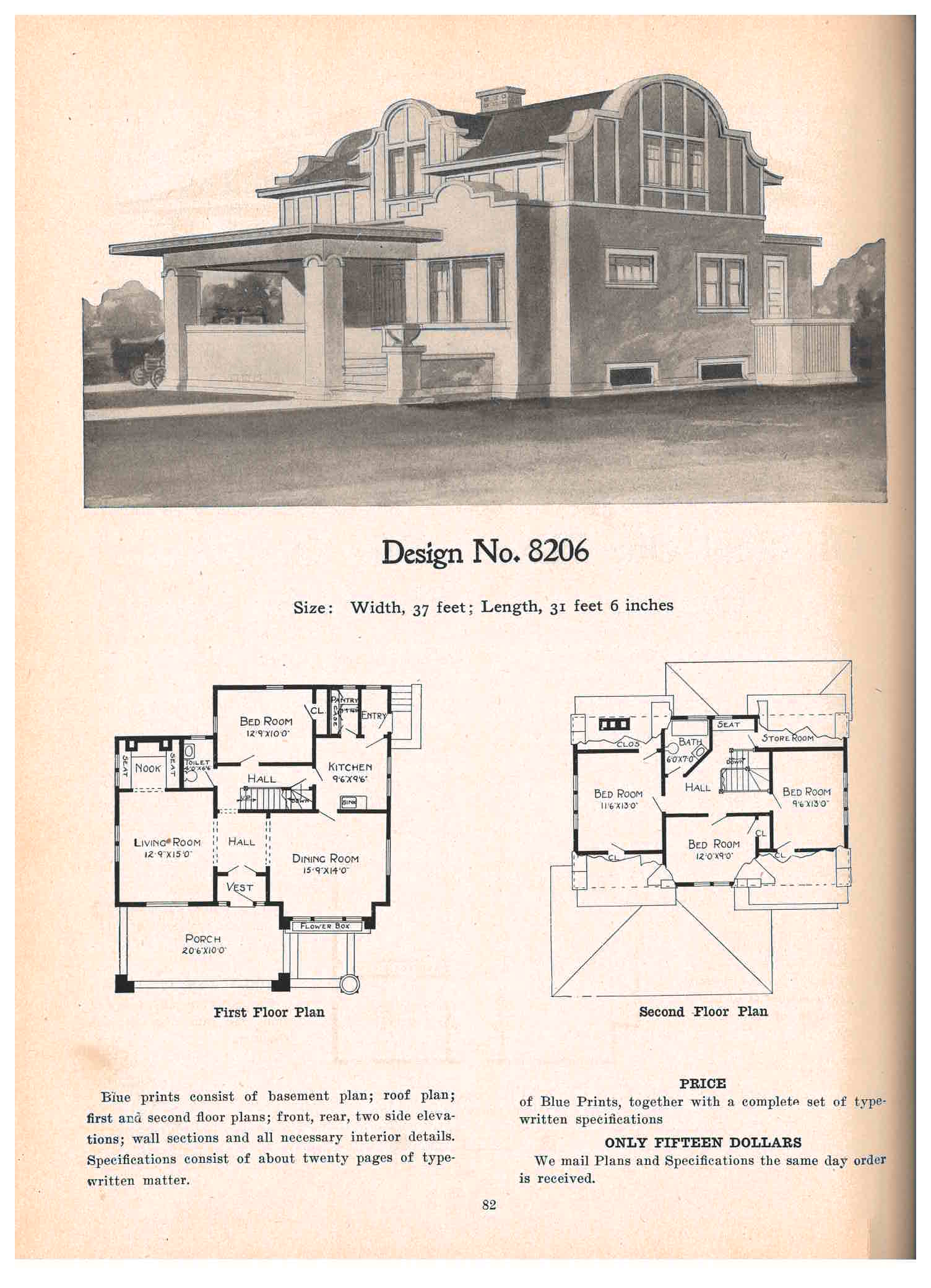

How to “Save Waste and Win the War” with Sherer-Gillett Grocery Counters

Can a particular kind of retail furniture help grocers save money and prevent food waste? In a World War I era trade catalog, Sherer-Gillett Co. promotes a piece of furniture designed for grocers to install in their stores. It was called the Sherer Counter, a bulk food storage system described as a way to cut down on waste and help with the war effort.

Let’s take a closer look at how Sherer-Gillett Co. encouraged the use of this counter for grocery stores. As shown below, the front cover of this catalog includes a quote by the U.S. Food Administration encouraging people to buy food with thought.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), front cover.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), front cover.

Then as we open this 1918 catalog, we are greeted with a quote by Sherer-Gillett Co. It also appears to be the title of the catalog. It reads, “buy food by the pound-not by the package.” This leads us to believe that Sherer-Gillett Co. encouraged the purchasing of food in bulk.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), unnumbered page [1].Next, we move on to the foreword. There, we learn this catalog was sent “to those who are ‘carrying on’ in food conservation.” Printed in 1918 during World War I, the catalog encouraged people by remarking, “it is pleasant to find that one’s daily vocation is in line with winning the war.”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), unnumbered page [1].Next, we move on to the foreword. There, we learn this catalog was sent “to those who are ‘carrying on’ in food conservation.” Printed in 1918 during World War I, the catalog encouraged people by remarking, “it is pleasant to find that one’s daily vocation is in line with winning the war.”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 2, Foreword.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 2, Foreword.

In these introductory pages, we discover this catalog appears to be focused on preventing food from being wasted and saving money for both the customer and grocer. To accomplish this, Sherer-Gillett Co. suggested food be sold and bought in bulk. The catalog mentions that food was frequently bought by the package but suggests dry goods might be suitable to sell by the pound. Some examples include cereals, dried fruits, crackers, cookies, beans, peas, and other similar types of food. However, the catalog also acknowledges the fact that some products, such as liquids and perishable foods, are more easily bought by the package.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 5, general information regarding the Sherer Counter and buying food by the pound.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 5, general information regarding the Sherer Counter and buying food by the pound.

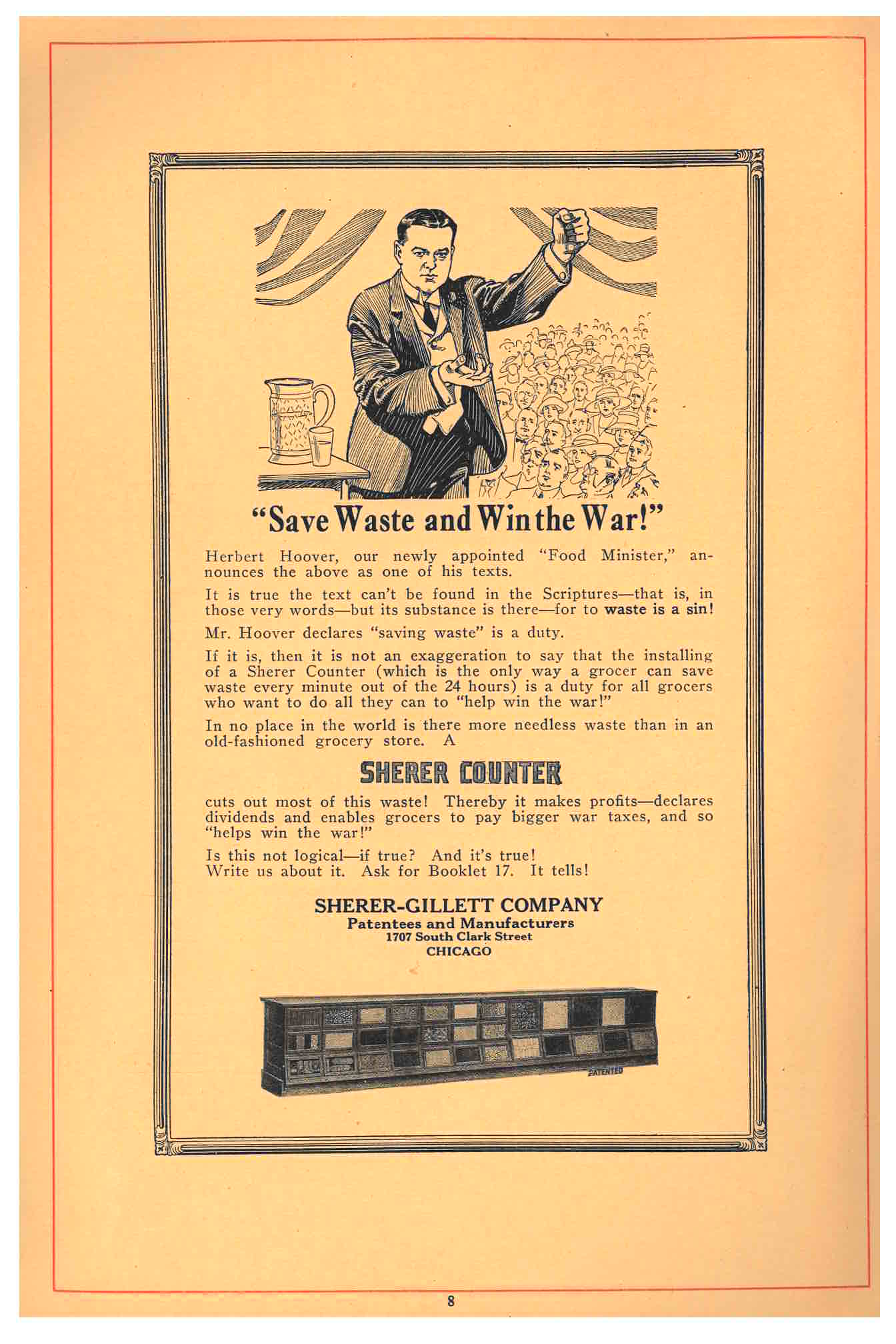

To help grocers and shop owners sell food by the pound, Sherer-Gillett Co. offered a piece of furniture called the Sherer Counter. The Sherer Counter was a grocery counter comprised of 31 bins with glass-front drawers used for the storage of various types of food while keeping everything fresh and clean. The Sherer Counter is illustrated at the bottom of the advertisement below.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 8, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Save Waste and Win the War!”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 8, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Save Waste and Win the War!”

To encourage the installation of the Sherer Counter, Sherer-Gillett Co. introduced a publicity campaign in collaboration with the Knight Co. of Chicago. Advertisements ran in grocer trade journals, and some are included in this catalog. These particular advertisements included a catchy title with a related illustration and an image of the Sherer Counter. These ads also encouraged the reader to request more information.

The purpose of the advertising campaign was to direct people’s attention to the idea of “saving” and encourage the use of the Sherer Counter for doing that very thing. According to this catalog, installing the Sherer Counter “helps save waste for the Dealer and the Consumer, and so—for the Nation. And if for the Nation, it helps win the war!”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), inside back cover, list of advantages of Sherer Counter.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), inside back cover, list of advantages of Sherer Counter.

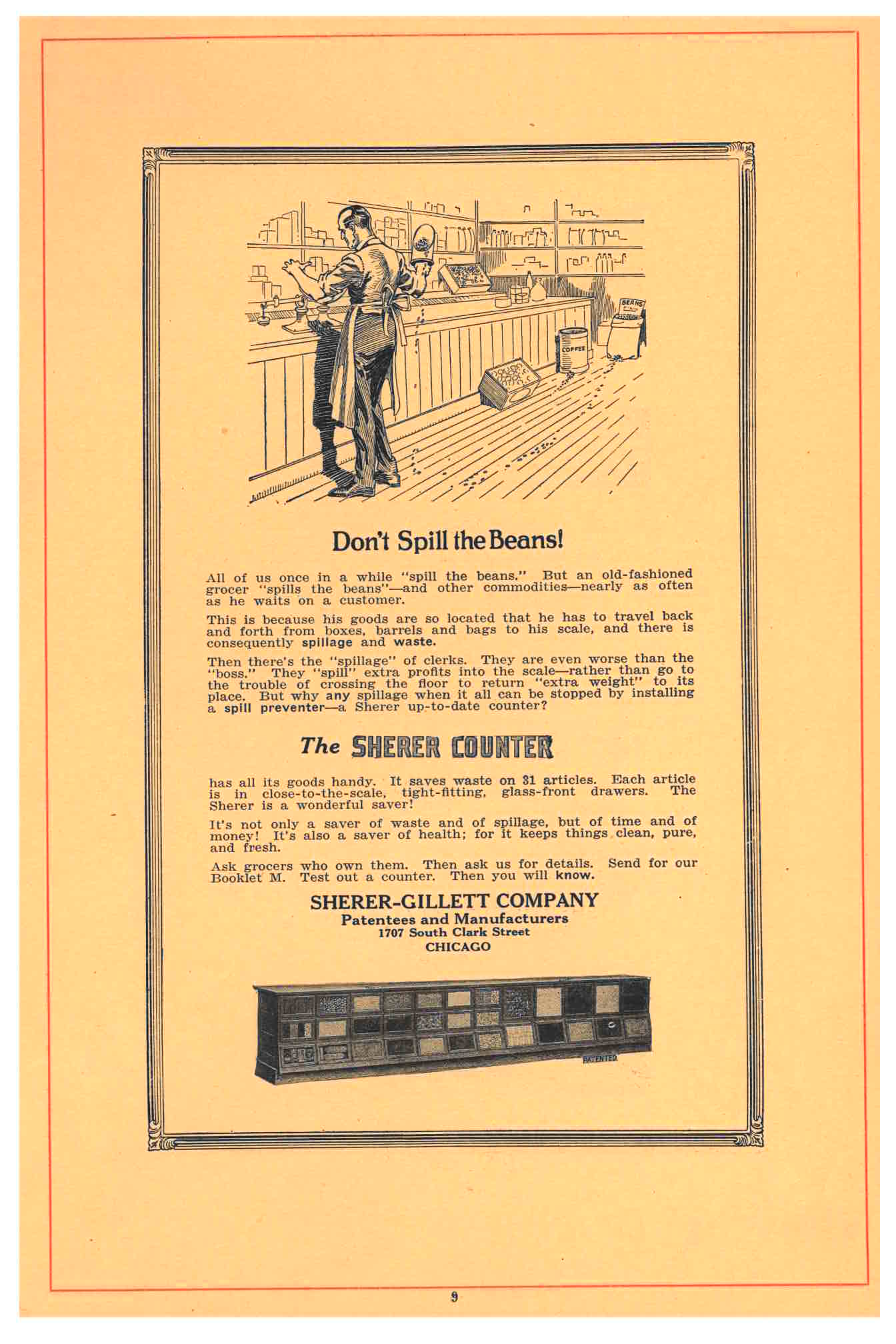

One advertisement begins with the phrase, “Don’t Spill the Beans!” It shows a trail of beans leading from a bag on the floor to a counter where beans are being weighed on a scale. As the beans are weighed, more beans are spilling onto the floor. This advertisement points out that if the grocer installed a Sherer Counter, the beans would be stored in “close-to-the-scale, tight-fitting, glass-front drawers” which might prevent beans from spilling onto the floor while being transferred from bag to scale.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 9, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Don’t Spill the Beans!”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 9, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Don’t Spill the Beans!”

Another advertisement weighs in on the idea of losing profit as food is spilled on the floor and wasted. The ad is titled “Why Sweep Out Your Profits?” and its illustration shows a pile of food that presumably fell onto the floor of a grocery store. The text reminds the grocer that keeping dry goods in boxes, barrels, and bags far away from the counter and scale leads to spillage and waste. In contrast, it suggests that a Sherer Counter which keeps food in specific bins near the scale cuts down on waste, thereby preventing lost profits.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 11, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Why Sweep Out Your Profits?”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 11, advertisement for Sherer Counter “Why Sweep Out Your Profits?”

Besides savings, profit, and preventing waste, another focus of the publicity campaign appears to have been cleanliness. An advertisement shown below and titled “No Waste Here!” illustrates a dog cleaning a food dish spotlessly clean from any crumbs. In this same advertisement, the Sherer Counter is described as a way to keep 31 types of food “immaculately clean-perfectly safe!” in its individual food bins.

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 13, advertisement for Sherer Counter “No Waste Here!”

Sherer-Gillett Co., Chicago, IL. “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918), page 13, advertisement for Sherer Counter “No Waste Here!”

This trade catalog, “Buy Food by the Pound-Not by the Package” (1918) by Sherer-Gillett Co., is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

How I Spent My Summer: Interning as a Virtual Web Archivist

As a current graduate student studying for my Master’s in Library and Information Science, I have a passion for digital archives and information organization. Throughout my own research, I have identified the importance of digital preservation and access to information and data. For my internship I worked with the Smithsonian Institution Archives Digital Services staff as part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Summer Scholars Internship Program.

When I first started this internship, I had the objective of learning more about the process of digital archiving and storing data. I had minimal knowledge of web archiving services and tools. This internship has broadened my knowledge beyond web archiving services while learning the importance of using various tools in order to improve the process. Learning ways to improve the collection and organization of stored data are important for correctly preserving the metadata and digital assets. My goals for this internship were to increase my knowledge in Dublin Core metadata schema, learn how to use web archiving services, and organize metadata. During my internship, I have learned new vocabulary along the way throughout the steps of the web archival process.

The workflow of metadata needs to be organized and precise. The collection that I have mainly worked on is the Smithsonian Institution Websites collection, which consists of Institution websites that have been crawled. Information also is updated within the Smithsonian Institution registry. The registry is an internal document that helps with tracking the Smithsonian websites and social media accounts. Over time, it is important to update this information due to the frequent change in contents on the web pages.

The main web archiving service we use is Archive-It, which is owned by the Internet Archive. It captures and preserves online electronic resources with a focus on access. Throughout my internship, I also was exposed to other web archiving services and tools, including Webrecorder, Conifer, Browsertrix, and Netlytic, to assist with the archival process to provide accurate crawls of each web browser.

There are many web and social media archiving terms I have learned:

- Seed: a URL to be crawled.

- Scope: an extent that the crawler will travel to discover and archive new materials captured.

- Crawler: collects majority of the contents in the data found from the web.

- Capture: the process of copying digital information into a repository for storage, preservation, and access purposes.

- Brozzler: crawling technology capturing dynamic contents.

- Quality Assurance: review of the crawled site compared to the live site.

- Accession: unique number assigned to specific group of archival materials.

- WARCs: international format standard that combines multiple digital resources into an archival container file.

- Host Lists: captured information of each host (storage of web content) site that has been crawled.

The use of the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) reference model has broadened my perspective of how each Archives’ team member works on their preservation workflows as web pages change constantly, such as managing the metadata, curating, and storing the information, and then providing access to the information for both staff and the public.

Throughout the archiving process, Dublin Core, a metadata standard for a wide range of networks and resources, is used to fill out descriptive elements within the Archive-It records to enhance the search and retrieval of archival collections. Creating an online listing of the Smithsonian Institution Websites is a way to have an available electronic bibliographic database that describes the content that each website and social media store. Since social media is very tricky to archive due to the dynamic content being showcased, using multiple tools to capture the data is important because it makes the web crawling process easier. Whenever any technical issue occurs there is always room to search for other alternatives to assist in the process that may seem to be the most appropriate based on a particular archival project.

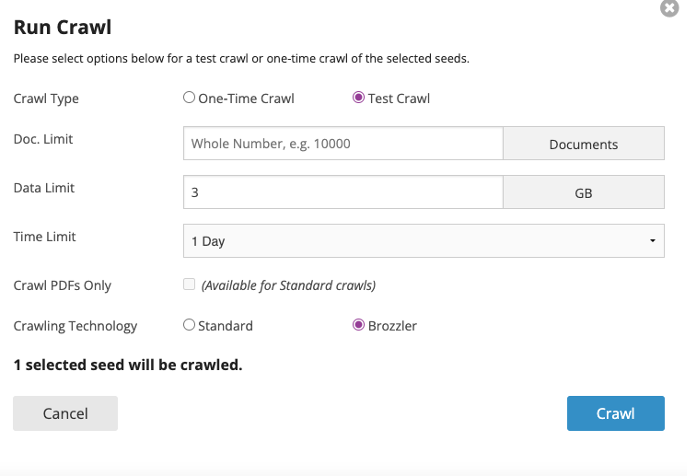

This is an example of a crawl that has been added through using Archive-It. Parameters include limiting the size and how long it should run:

Screencapture of Archive-It Run Crawl parameters.

Screencapture of Archive-It Run Crawl parameters.

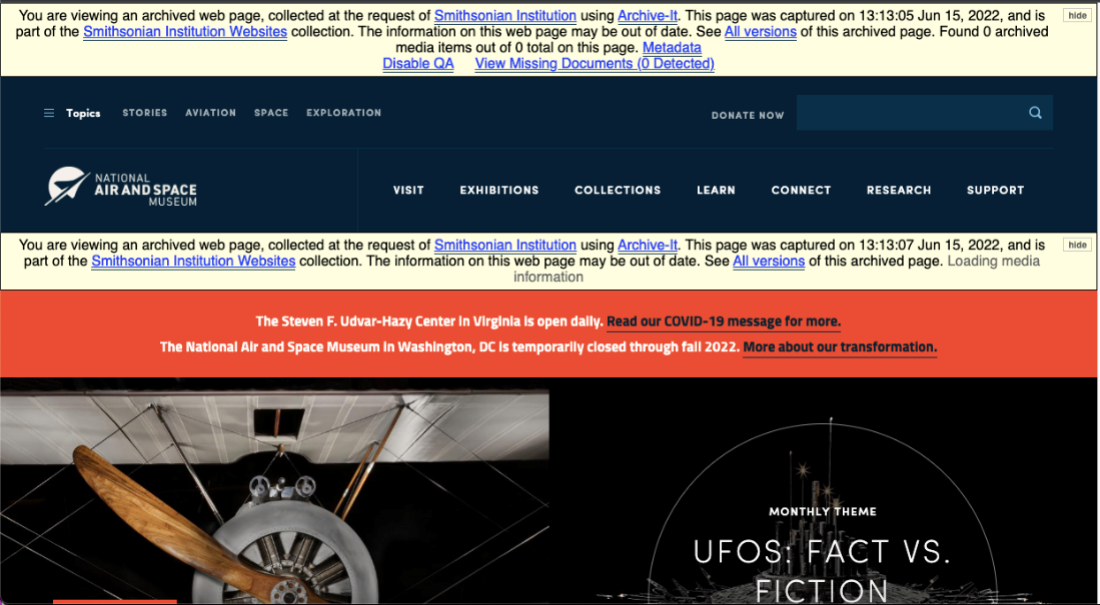

This is one of the examples of a previously crawled Smithsonian website with Archive-It for the National Air and Space Museum from January 3, 2013. Notice the images, web page layout, and logo on the website compared to the next crawl.

Screencapture of National Air and Space Museum website from 2013.

Screencapture of National Air and Space Museum website from 2013.

On June 15, 2022, I crawled this website. See that the newly posted images captured at the time and the logo are updated. Having this information digitally archived is important to have a way to look back at Smithsonian websites and to have them historically documented for the future.

Screencapture of National Air and Space Museum website in June 2022.

Screencapture of National Air and Space Museum website in June 2022.

When I went to American Library Association Annual Conference 2022 in Washington D.C., I stopped by the Archives’ office. It was wonderful to meet the team in person and take a tour with my supervisor. I was able to meet with the digital archivists to see firsthand some of the archival processing being done on the website collections that I learned how to capture as part of my internship.

Did I mention I saw boxes of floppy disks waiting to be copied and pallets full of boxes of Smithsonian collections waiting to be processed? Fascinating, right?

My visit to the Collections area at the Archives.

My visit to the Collections area at the Archives.

Throughout this internship, I have gained a real-world perspective of digital archival works. This experience has prepared me for the aspect of the digital archive workplace. My passion for digital archives has increased and opened my mind to possibilities to advance my technical and archival skills. Working virtually with the digital services staff has been an adventurous learning experience. Although I have gained real-world skills in web and social media archiving, digital curation, metadata, and digital preservation, I always still have the desire to expand my knowledge further.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives & Wikidata: Smithsonian Research Online

This is the fifth part of a series sharing Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ work with linked open data and Wikidata. For background and overview of current projects, see the first several posts in the series.

FailureWhen pursuing data projects, sometimes failure is the most successful outcome you can have. Perceived “stumbling blocks” you may encounter can profoundly teach you about your data, your projects, and what it is you need to course correct (as well as how much resource you may be lacking!). Our Smithsonian Research Online experience with Wikidata is a perfect example of one such learning opportunity.

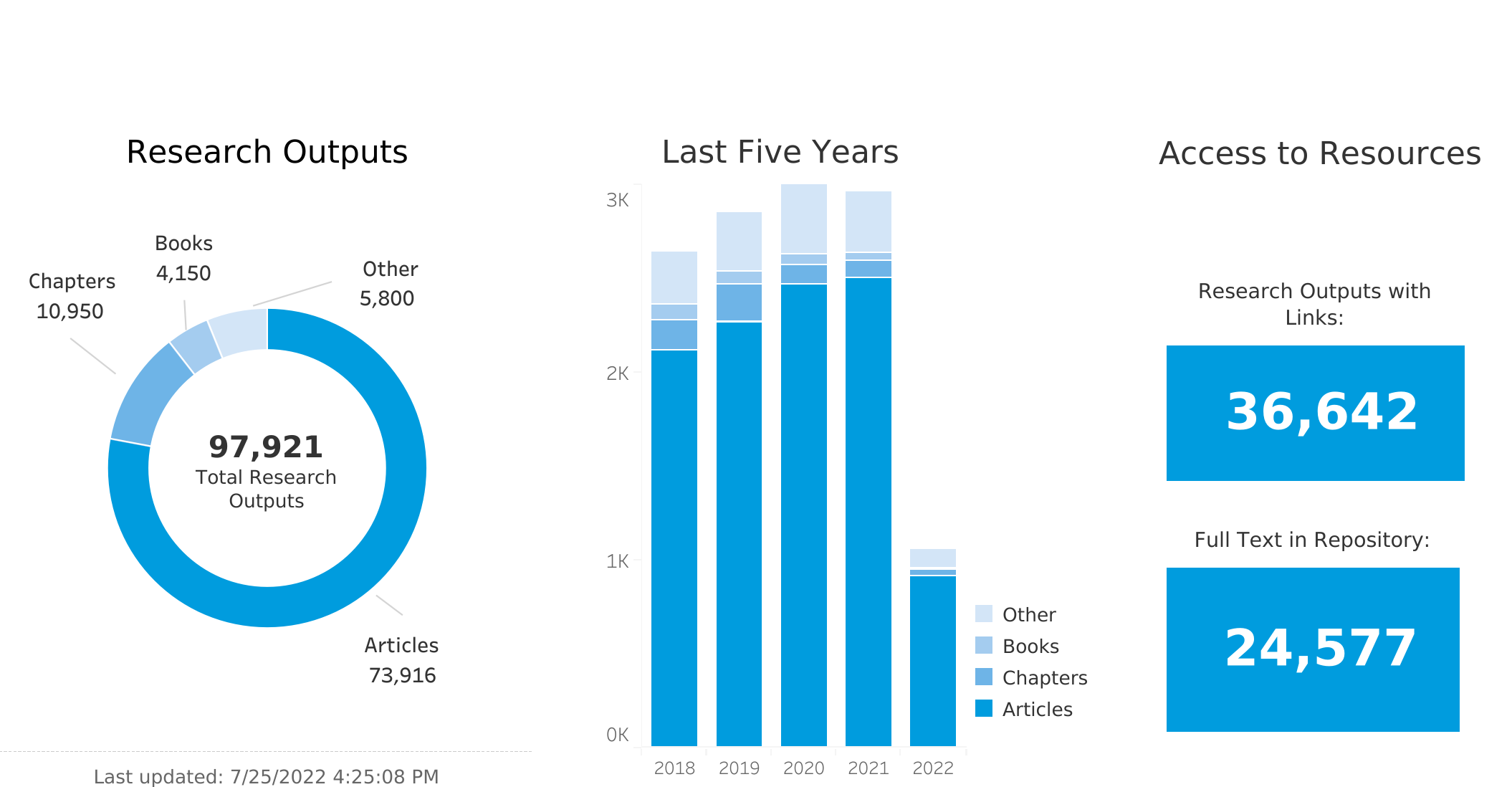

Linked dataAs research information management professionals, our team is knee-deep in the types of data that Wikidata was built for. The Smithsonian Research Online program at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has collected and managed data about the research published by scholars at the Smithsonian Institution for almost fifteen years. We now are just shy of 100,000 research outputs ranging from journal articles, book chapters, and books, to guest lectures, blog posts, and even a few patents. Along the way, we have identified over 150,000 distinct agent names found within this bibliographic corpus and have maintained a minimal ability to associate those names to individual persons. But the workflows and the technical support needed to maintain them are both taxing. So, when the opportunity arose to learn about the wiki-world and its promise for helping us with authority control, the Project for Cooperative Cataloging Pilot naturally interested us.

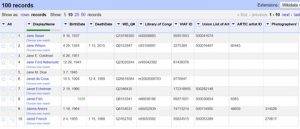

Selection of Research Output statistics from Smithsonian Research Online.

Selection of Research Output statistics from Smithsonian Research Online.

Bibliographic data in Wikidata is so important that many tools have been developed to help move us forward. Aside from the myriad existing projects and bots importing bibliographic datasets into Wikidata, the Scholia project is a notable example of how bibliographic data, once in Wikidata, can show off amazing stuff. In fact, they use the Smithsonian as one of their examples for organizations. As Scholia relies heavily on Wikidata’s bibliographic content, linking the publications to their authors becomes a key component of enriching this data. One tool for doing so is the Author Disambiguator. The importation of metadata from sources like Crossref is easy enough, but it takes some brain power to make sure that the author named in the paper is a specific person with an item in Wikidata. That is where the author disambiguator comes in: it allows someone to run a fuzzy search on a name and then groups results in a way that most likely indicate the same name. From there, it is a matter of replacing the statement on a publication’s Wikidata item that holds the name string with a statement that actually associates and connects the publication to the author’s item itself in Wikidata.

Of course, none of our work could be done without tools like SPARQL query service, QuickStatements, OpenRefine, and more. We used each tool extensively. The SPARQL query service allowed us to evaluate what was in Wikidata already. For example, when working with organizational data about the Smithsonian, we needed to see what belonged to the Smithsonian, and SPARQL allowed us to visually graph the entities. We could also use Listeria to generate tables with the core properties we were looking to ensure were correct in Wikidata. OpenRefine’s reconciliation service was something we used often to process our data about organizations and people. Finally, QuickStatments made easier work of ingesting more than a few records at a time.

What we hope to do with this (Failure Continued…)When we set out on our ambitious collaboration with the Project for Cooperative Cataloging, we hoped to start by cleaning up Smithsonian organizations, then add Smithsonian authors, and finally populating with Smithsonian publications—a big project with even bigger questions.

We accomplished a lot of these tasks. First, we made sure that the organizations in Wikidata for the Smithsonian were represented, had authoritative data about them including external identifiers, and that they were properly related to the Smithsonian itself—an element of belonging that can be difficult to maintain in Wikidata. However, the actual process of fully modeling organizations and buildings posed more challenges than we anticipated. After all—what is a museum? Is it an organization that occupies a building? Or is a museum a building that holds exhibitions?

In some cases, the distinction between building and organization was clear—we have two museums (the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery) that occupy one building (the Old Patent Office Building, now known as the Donald W. Reynolds Center). But what do we do with the ones that were treated as both a building and an organization? This posed real challenges, especially as the Smithsonian now has two new museums that are a decade away from finding a home in an actual building. So, the inception date for these museums is often quite different from the opening date, and statements are not consistent across our museums. This can make using the data challenging since you cannot easily query things based on a consistent set of properties. Additionally, the matter has yet to be settled within the Wikidata community, where there are arguments for and against establishing separate entities for items which currently conflate buildings and organizations, especially when the building does not have its own unique name. Solving this problem is not as easy as creating those separate items ourselves, as other Wikidata editors who disagree with the practice may merge our newly created items back into one conflated entity. We continue to refine our approach.

Next, we made sure that our researchers had entries in Wikidata. Happily, we found that most already had them, thanks to past projects between the Smithsonian and Wikidata. However, the project posed a challenge: Who should we focus on? Many staff members across the Smithsonian coauthor publications even if their primary job duties do not include research. There are countless fellows, post-docs, pre-docs, interns, contractors, and affiliated agency staff who do work and publish at the Smithsonian. Finally, there are plenty of researchers who have an affiliation with the Smithsonian even if they are not employed or located here. Do we represent this information in Wikidata? If so, how far back do we go? (Or do we even try to be retrospective?) This was a decision we needed to make, joining the many other decisions we were presented with along the way, resulting in a bit of decision fatigue. We did have a logical set of data, though—we have an existing linked data project in the form of our VIVO implementation, Smithsonian Profiles. At the very least, we made sure the people in our profiles were also in Wikidata, with some core properties to at least associate them with the Smithsonian.

The area we failed in accomplishing was how to ensure that publications from these researchers were properly included in Wikidata and properly attributed to the person. For example, we did queries in our system for the researchers in Smithsonian Research Online who had the highest number of co-authorships, and began to run the Author Disambiguator to associate each author’s Wikidata entry with the publications that had that author’s name as a name string. What this does is find a name string in the author name string property statement for a publication, lets you determine if it is a known author with a Wikidata entry, and then it removes the name string from the author name string property and adds the correct Wikidata item for the author in the author property statement. This truly links the publication’s Wikidata item to the author’s Wikidata item, thus creating a much richer knowledge graph and enabling things like Scholia to work. Even with the increased efficiency of using the Author Disambiguator, a project to associate thousands of researchers with thousands of publications still requires a lot more staff time than we had available to pursue.

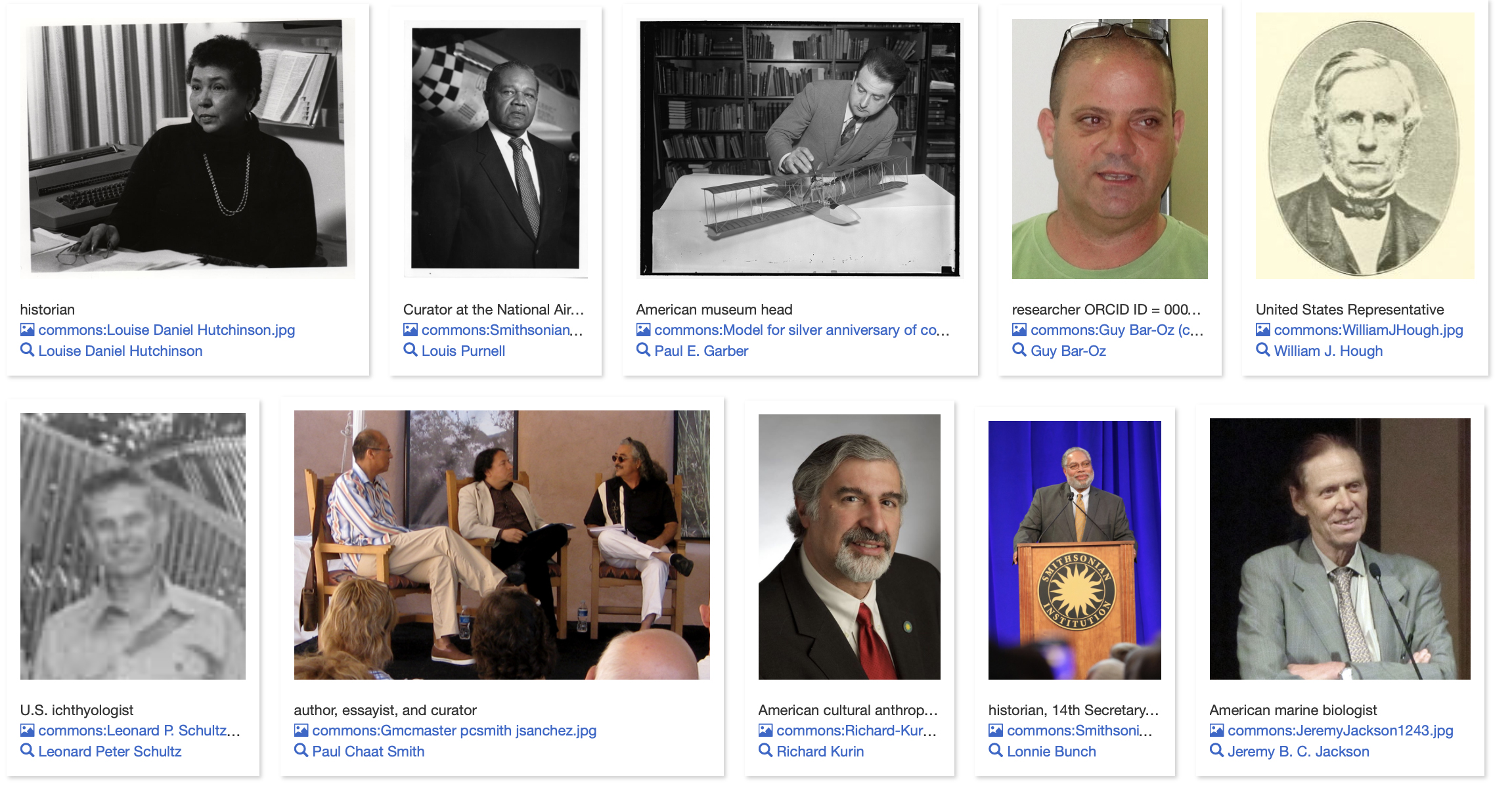

Screencapture of Smithsonian researchers represented in Wikidata Query.

Screencapture of Smithsonian researchers represented in Wikidata Query.

We may not have perfected our data representation in Wikidata, but what it offered us instead was a robust introduction to data modeling and figuring out the potentials of the Wikibase software in generating linked data. Now that we have some representation of our researchers within Wikidata (and at least know the fundamentals of how this works), our next experiment is to take those researchers and create a local wiki ecosystem that can connect to Wikidata, but still offer us the ability to control the exact set of data points we want to add for each researcher—which would help us immensely when we need to deal with two researchers sharing the same name, or when researchers have multiple names in the literature—whether from different abbreviations, naming conventions, or changes in names. One of the persistent challenges for bibliographic data is associating and teasing apart ambiguous names. One author can have their name listed in many different versions – especially if their name changes from marriage, gender transition, or even from variations in citation style abbreviations. (Not to mention how names in publishing are often shoehorned into western conventions, as explored for Vietnamese names in this Twitter thread.) On the other hand, you can have multiple people with the same name (even at the same institution!). Having a platform like Wikibase could allow us to maintain those distinctions, and then relate our data to the appropriate person’s record.

The potential strength of Wikibase lies in the flexibility it offers to accommodate local modeling of data. In the case of Smithsonian organizational data and the relationship among our different museums, research centers, and other units, having a locally installed Wikibase gives us complete control over how we model our data while still linking with rich external sources of information. Wikidata is a revolutionary experiment in democratizing data. The benefits of removing gatekeepers to data are many, and we are excited to see the fruits of this. Yet it is clear we aren’t quite ready to fully commit to tearing down that gate. We still need (at the very least) a garden border, so we can tend our own data the way we see fit. Can Wikibase provide that service for us? We shall see.

A Journey With StoryMaps

As a Master of Library and Information Science student at the University of Southern Mississippi School of Library and Information Science, I have learned that Information Literacy is a critical skill for the 21st century. Understanding the current challenges in administering extensive quantities of information, and using information through a critical lens, is paramount for the demands of the modern information society.

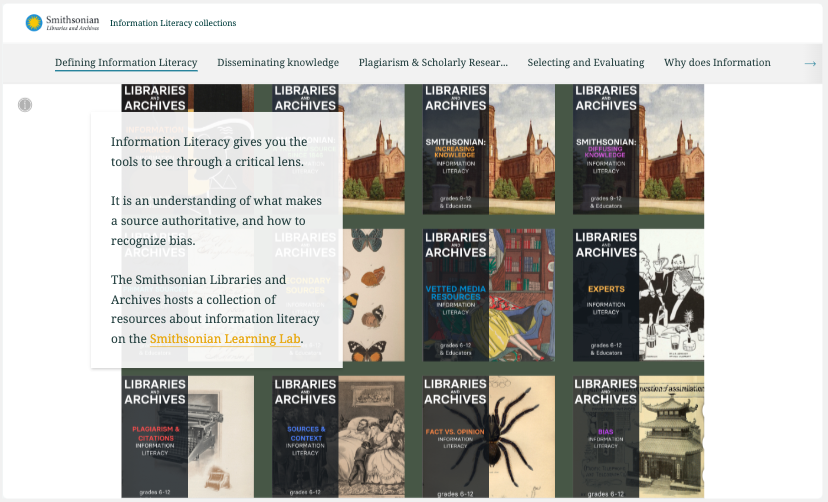

This summer (June 2022), I interned with the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Education Department, which has a program on Information Literacy. As part of the program, they are building Information Literacy Collections in Smithsonian Learning Lab. My first project was to write a StoryMap using ArcGIS StoryMaps builder’s digital application. Different Smithsonian units are telling diverse stories utilizing this application, and my work was to narrate a story about the Information Literacy Collections available in Learning Lab.

Screen capture of Information Literacy StoryMap.

Screen capture of Information Literacy StoryMap.

I started my story by defining what Information Literacy is and moved on to highlighting how the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives disseminates information. Then, I continued developing three significant concepts in the Smithsonian Learning Lab collections: how to avoid plagiarism and use authoritative citations, how to evaluate and select information, and what scholarly research is. My story ended by looking toward the future, emphasizing other types of literacies such as civic literacy, environmental literacy, and social justice literacy. I concluded by stressing why Information Literacy matters: to prevent mis- and disinformation and empower individuals to be more informed citizens.

The collections in Smithsonian Learning Lab were my focal sources of information, which I had to select, analyze and synthesize for the story. Choosing images from the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives image collections became enjoyable but more difficult than imagined. I hope this StoryMap provides an overview of the importance of Information Literacy for learners and educators and shows the numerous resources available in the Smithsonian Learning Lab.

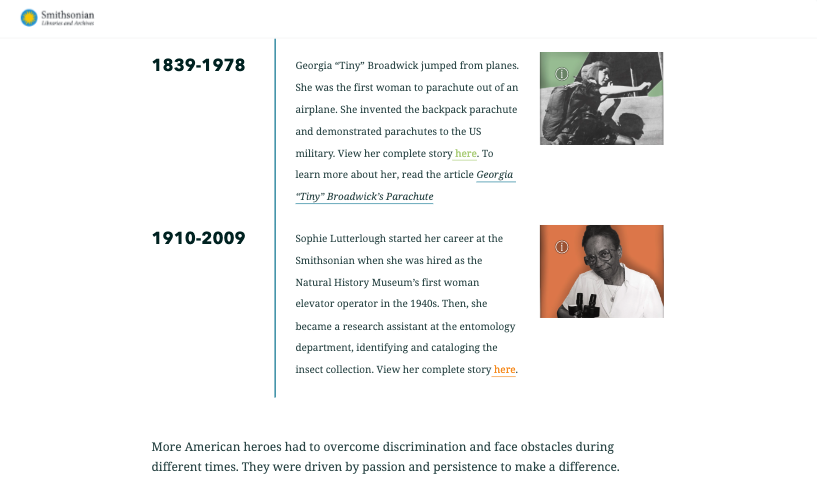

After finishing my first project with a good feeling of accomplishment, I embarked on my second project: another StoryMap focused on the online series Women in America: Extra and Ordinary. The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives hosts this collection of twenty-four extraordinary women to honor their contributions. This StoryMap will highlight the stories of Elleanor Eldridge, Senda Berenson Abbott, Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick, Sophie Lutterlough, Mary Edwards Walker, Zitkala-Sa, Anna Way Wong, and Lydia Mendoza. In this story, I included songs featured in the digital collection. The outcome is an interactive story that will help us remember the passion of these women and their fights against discrimination.

Screen capture of Women in America StoryMap, coming soon.

Screen capture of Women in America StoryMap, coming soon.

Alongside these two StoryMaps, I worked on a third project, starting a bibliographic list on Information Literacy. The purpose of this list is to provide a selection of resources and materials on Information Literacy and Critical Information Literacy (CIL). It includes freely available resources within the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives; for example, What is a Primary Source?, databases, books, articles, websites, digital evaluating resources, guidelines, frameworks, journals, literacy toolkits, and resources on civic, social and environmental literacy. Crafting this list helped me understand the scope of information literacy and how vital it is to inform critical thinking since we live in a world with unfettered access to unverified information. I learned that museums focus on visual literacy, and the article Growing Literacy Skills with Visual Thinking Strategies on Virtual Art Museum Tours is a noteworthy reading. This list is under review, but there are some resources that I encourage you to explore, such as Civic Online Reasoning, on how to evaluate online information.

My time here has been stimulating. I am impressed by the many resources and educational opportunities the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives offers; hence, I am very thankful for this thrilling experience. Above all, I have learned new skills and improved others, but most importantly, I engaged with insightful colleagues who helped me do better constantly.

Join us for “Smithson to Smithsonian: The Legacy of James Smithson” on July 27th

Over the course of 175 years, the Smithsonian has grown to encompass 21 museums and nearly a dozen research centers—becoming a global organization working across history, culture, and science. How a stranger’s legacy became the world’s largest museum and research complex is a story full of surprising twists and turns of fate. What do we know about the Smithsonian’s mysterious founder, a man who left his fortune to the United States, a country he never visited?

To celebrate the launch of our 175th-anniversary online exhibition, Smithson to Smithsonian, we’ll explore the life and legacy of founder James Smithson with a panel of experts.

Smithson to Smithsonian: The Legacy of James Smithson

Wednesday, July 27, 2022, 5:00 pm

Zoom Webinar

Featuring:

- Heather Ewing, Author of The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian and Associate Dean, New York Studio School

- Leslie Overstreet, Curator of Natural-History Rare Books, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

- Richard Stamm, Curator of Smithsonian Castle Collection, Smithsonian Institution

- Steven Turner, Author of The Science of James Smithson and Curator Emeritus, National Museum of American History

We are committed to providing access services so all participants can fully engage in these events. Optional real-time captioning will be provided. If you need other access services, please email SLA-RSVP@si.edu. Advanced notice is appreciated. This program will also be recorded and made available following the event.

This program is part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ commemoration of the 175th anniversary of the Institution’s founding.

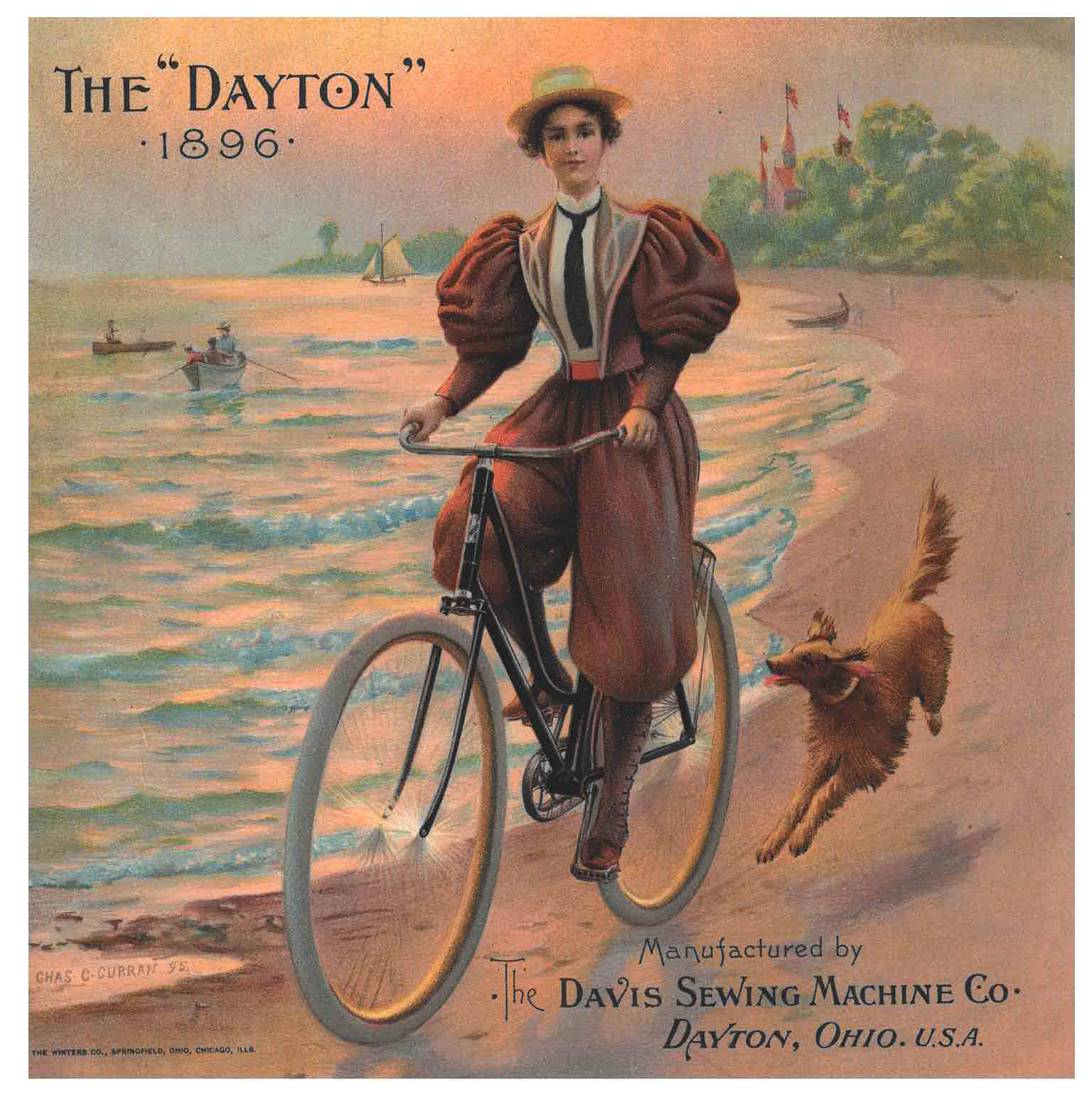

Pedalling Through Time With Davis Sewing Machine Co.

Recently, I stumbled across a trade catalog that made me pause. As I looked at its vibrantly illustrated front cover, I thought of relaxing, summer days at the beach. It shows a bicyclist riding along the shoreline, a dog following closely behind, and boats in the distance. I also noticed one more thing. The name of the company refers to sewing machines while the front cover illustrates a bicycle. That observation sparked my curiosity to explore the pages within this catalog.

The catalog is titled Dayton Bicycles (1896) by Davis Sewing Machine Co. With a name referencing sewing machines, it might come as a surprise that the company also manufactured bicycles. According to this catalog, the Davis Sewing Machine Co. presented the Dayton Bicycle to the public early in the season of 1895, one year prior to this catalog.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), front cover.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), front cover.

It mentions that the Dayton Bicycle was not “the product of a new and untried establishment.” Instead, the production of this bicycle resulted from “a careful and comprehensive study” of both the methods and requirements necessary for manufacturing bicycles.

It also highlights that Davis Sewing Machine Co. had already been manufacturing machinery for more than 25 years. Based on the name of the company, the machinery being referred to is presumably the sewing machine. The Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library also includes some of their sewing machine catalogs.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), title page.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), title page.

This particular catalog includes several pages providing technical information and details regarding the construction and manufacture of the 1896 Dayton Bicycle. Besides images of these models, it also elaborates on specific parts of the bicycle.

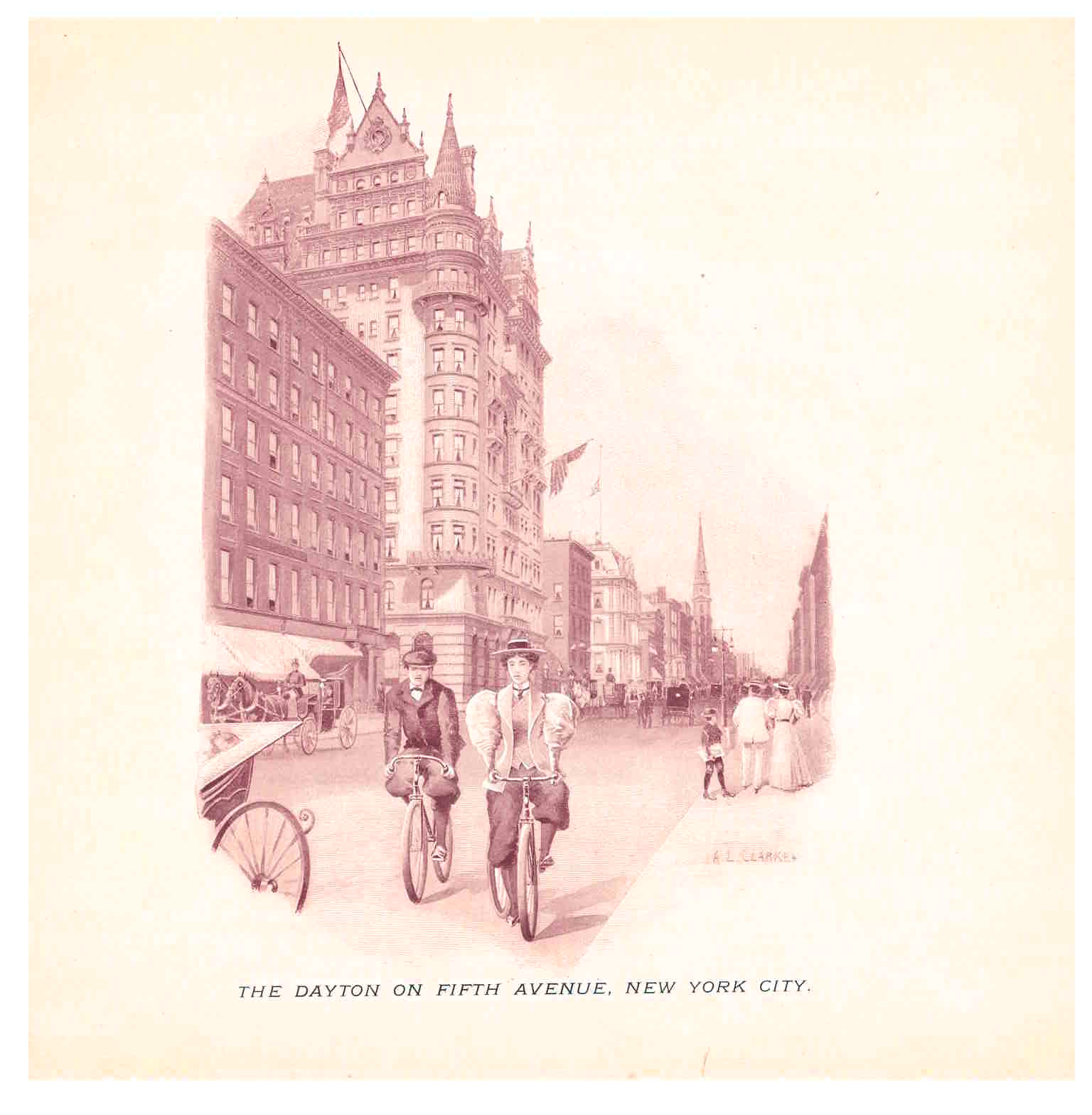

The Dayton Bicycle itself was described as having “graceful lines and beautiful design” and “combining extreme strength with perfect symmetry.” Scattered throughout the pages of this catalog are a variety of illustrations showing the bicycle in action with individuals riding in such places as the beach, park, or city.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), “The Dayton on Fifth Avenue, New York City.”

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), “The Dayton on Fifth Avenue, New York City.”

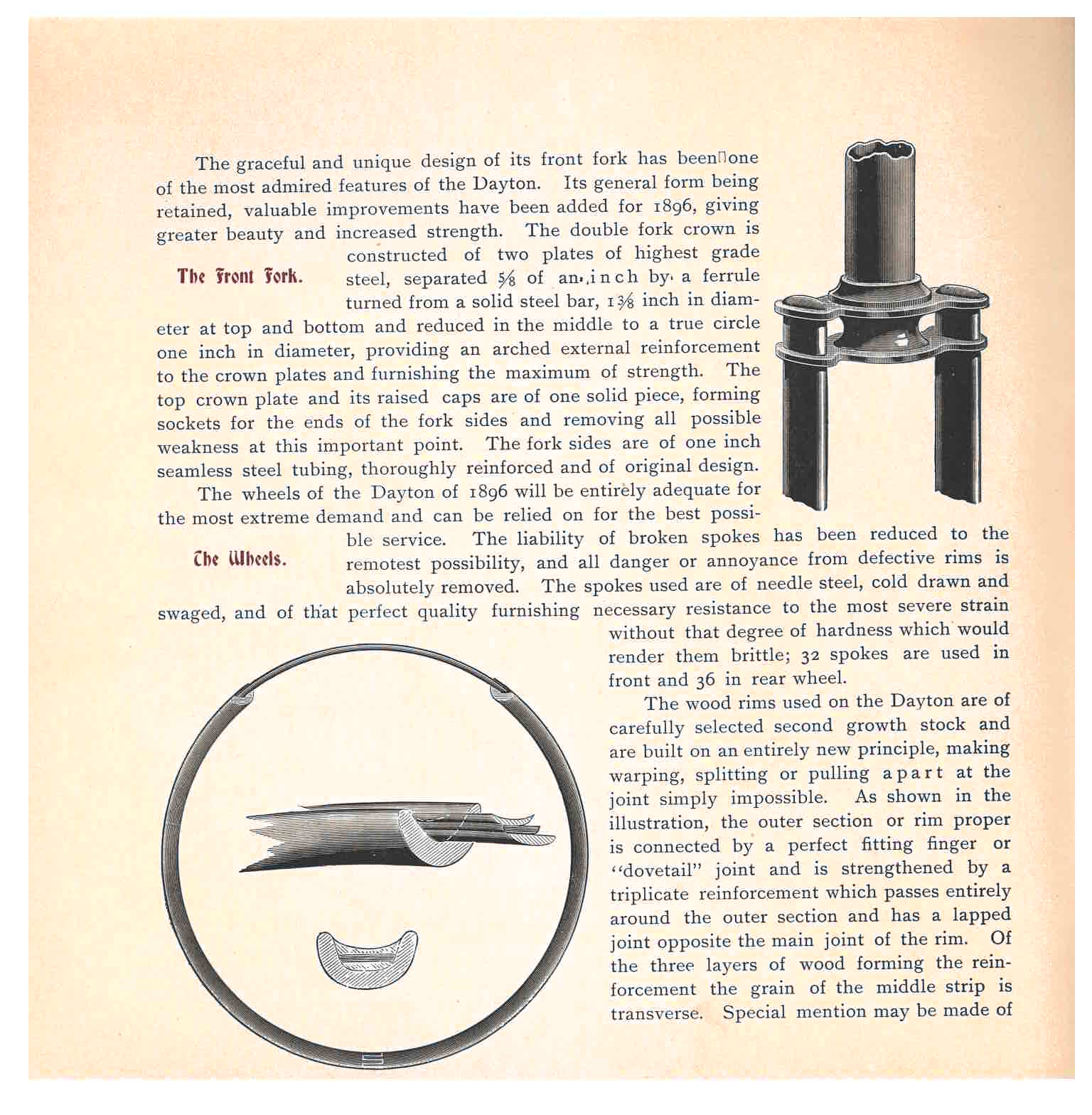

A feature of the Dayton Bicycle was its wood rims, which according to this catalog, were constructed to prevent warping, splitting, or pulling apart at the joint. Reinforced with three layers of wood, it used both a dovetail joint and lapped joint. More details and an illustration are shown below. The rims were finished in either natural wood or stained.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Front Fork, Wheels, and Wood Rims of bicycle.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Front Fork, Wheels, and Wood Rims of bicycle.

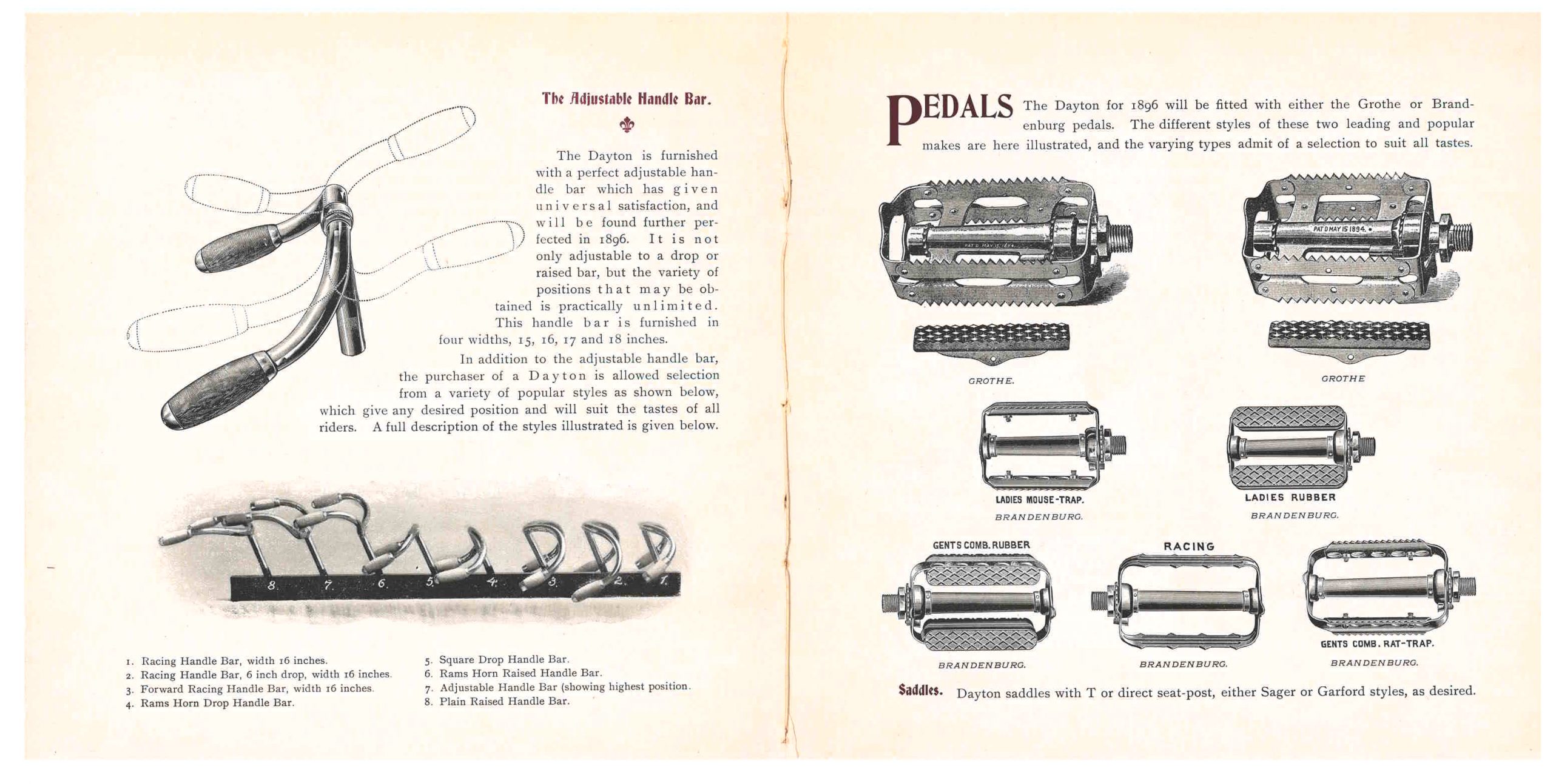

Bicyclists had a variety of handlebars to choose from, such as the plain raised handlebar and several designed for racing. The adjustable handlebar is shown below left (top image and number 7 at the bottom). This feature allowed the rider to adjust the handlebars to a variety of positions, including a drop or raised position. Adjustable handlebars were available in widths of 15, 16, 17, or 18 inches.

As for pedals, the 1896 Dayton Bicycle was outfitted with either the Grothe Pedal or Brandenburg Pedal. The various styles for these pedals are illustrated below (right), including one for racing.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Adjustable Handle Bar and Styles of Handlebars (left page) and Pedals (right page).

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Adjustable Handle Bar and Styles of Handlebars (left page) and Pedals (right page).

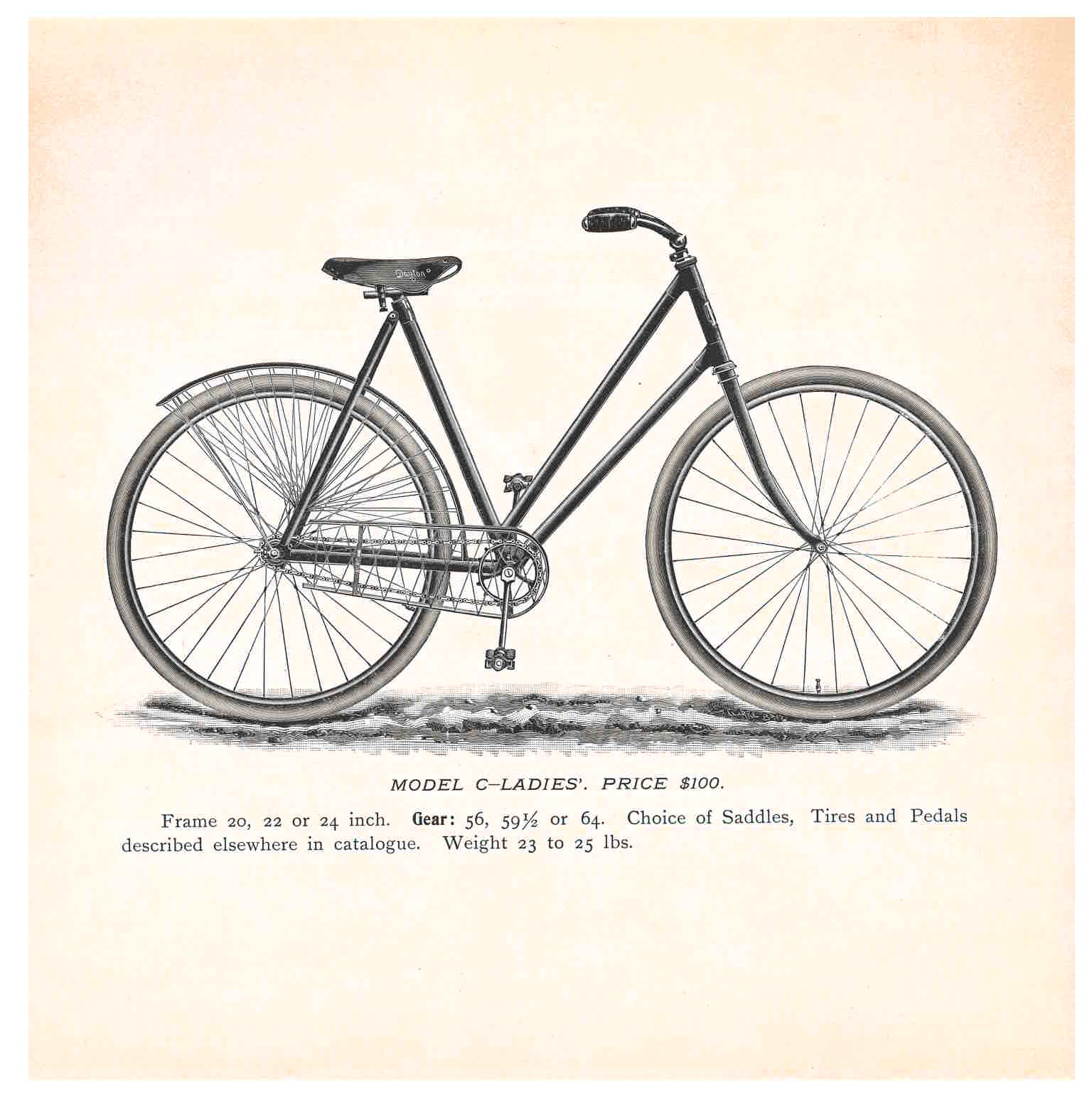

Moving further along, the catalog provides illustrations of several 1896 models. One of these is the Model C-Ladies’ Bicycle. Weighing 23 to 25 pounds, it was built with a frame measuring 20, 22, or 24 inches.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Model C-Ladies’ Bicycle.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Model C-Ladies’ Bicycle.

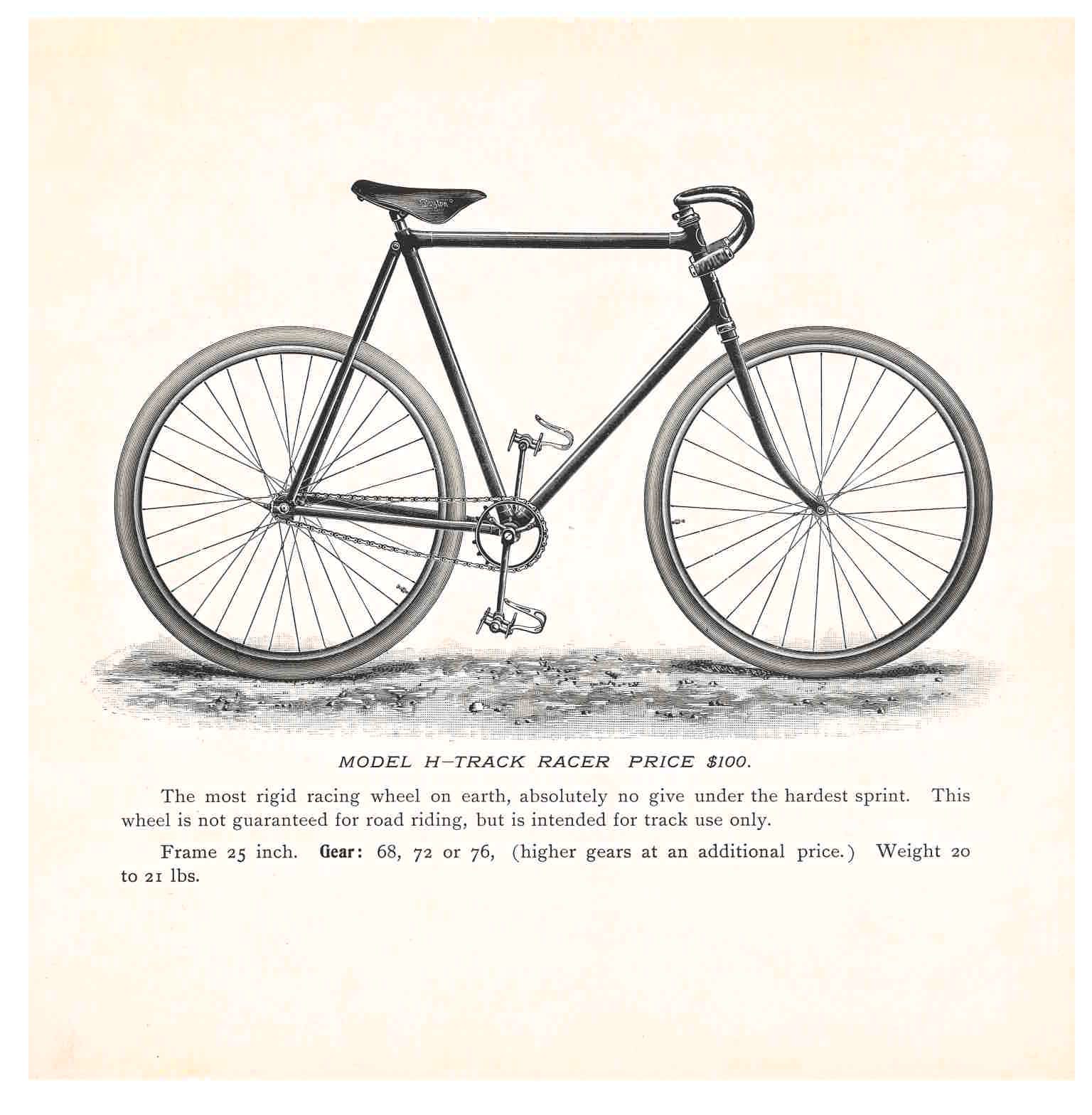

The Model H-Track Racer, shown below, was described as “the most rigid racing wheel on earth, absolutely no give under the hardest sprint.” Weighing 20 to 21 pounds with a 25-inch frame, it was designed for use on only tracks and not meant for riding on the road.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Model H-Track Racer.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), Model H-Track Racer.

Other models include the Roadster and Tandem bicycles. The Model M-Single-Steering Tandem, built to accommodate two riders, is shown below (right). Weighing 40 pounds, its frame was available as a 23- or 25-inch bicycle. The Dayton Racing Tandem is shown below (left) and described as possessing graceful lines and a stiff frame. It is shown being ridden in what appears to be a race.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), “The Dayton Racing Tandem at the National Capital” (left page) and Model M-Single-Steering Tandem (right page).

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), “The Dayton Racing Tandem at the National Capital” (left page) and Model M-Single-Steering Tandem (right page).

Just like the catalog begins, the back cover shows another vibrant illustration. This one is titled “An Elopement” and depicts a couple taking off on a Tandem, presumably a Dayton Tandem. Far in the distance, a horse and carriage speeds down the road towards them.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), back cover.

Davis Sewing Machine Co., Dayton, OH. Dayton Bicycles (1896), back cover.

Dayton Bicycles (1896) and other trade catalogs by Davis Sewing Machine Co., including sewing machine catalogs, are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives at the Smithsonian National Education Summit

Join the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives at the Smithsonian National Education Summit on July 27th-28th, 2022. This is a free, two-day, online and in-person program hosted by the Smithsonian for educators, librarians, media specialists, and policymakers nationwide.

We will be participating in two events. The first is a webinar, Of Source Not!, on July 27th at 1 pm EST. Join this session to hear from our head of education, Sara Cardello, our historian, Pam Henson, and a past Neville-Pribram Educator, Mike Skomba, as they share the importance of primary sources, including oral histories, how to break them down, and what to watch out for.

Of Source Not!, on July 27th at 1 pm EST featuring Mike Skomba, Sara Cardello, and Pam Henson.

Of Source Not!, on July 27th at 1 pm EST featuring Mike Skomba, Sara Cardello, and Pam Henson.

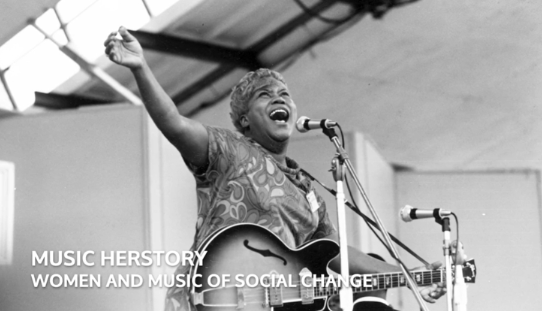

The second way to interact with Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ materials while attending the summit is through our behind-the-scenes video, From Nursery Rhymes to Punk Rock. This is an all-access backstage pass to our new exhibition, Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change, which explores the rich contributions of American women across a wide range of musical genres.

From Nursery Rhymes to Punk Rock video will introduce the Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change exhibition to educators.

From Nursery Rhymes to Punk Rock video will introduce the Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change exhibition to educators.

The overarching theme for the summit is Together We Thrive: Creating Our Shared Future Through Education. Beyond the Libraries and Archives contributions, there is a wide variety of outstanding programming to check out. Learn more about it from the Undersecretary for Education, Dr. Monique Chism here and take a second to register for the event here. See you there!

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Unveil “Music HerStory”

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage open a new exhibition, “Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History June 22. “Music HerStory” will be on display through Feb. 20, 2024.

An exhibition case from “Music HerStory”, now open in the National Museum of American History.

An exhibition case from “Music HerStory”, now open in the National Museum of American History.

Women’s leadership in music and social change is central to the American story. From people’s earliest musical encounters to the formation of complex social identities, the American musical landscape would not be what it is today without the countless contributions of women changemakers, groundbreakers and tradition-bearers. “Music HerStory” explores these contributions through unique media collections from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, the Center for Folklife and Culture Heritage and around the Smithsonian.

The exhibition, presented in both Spanish and English, will feature Ella Jenkins, an award-winning musician whose songbooks have taught children about a diversity of cultures and languages for over 50 years; Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the “Godmother of Rock ’n’ Roll” and a pioneer of spiritual music; Lucy McKim Garrison, an abolitionist musicologist who documented African American music in the 1800s; Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last sovereign monarch of Hawaiʻi, who was a gifted and prolific composer; and singers Dolly Parton, Kitty Wells and Loretta Lynn, who shaped the country music genre.

“With more than 16,000 musical instruments, 100,000 pages of sheet music, 80,000 recorded music tracks, hundreds of books and hundreds of musical activities annually, the Smithsonian is among the world’s largest museums of music,” said Meredith Holmgren, curator of American women’s music and this exhibition. “And yet, many of these musical resources remain unknown to the public. This is especially true for our music collections that relate to women’s history. Women have made incredible contributions to the history of music and social change. We are delighted to bring many of these stories to life in the exhibition.”

“Music HerStory” tells the powerful stories of women who used music to challenge gender stereotypes; bring forth revolutionary self-expression; reimagine political and social change; push boundaries for the labor movement, women’s health and education; and deliver victories for temperance and suffrage activism. Objects on display include the Jean Ritchie’s dulcimer made by George Pickow (Viper, Kentucky, 1951), Elizabeth Cotten’s Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar (Folkways Records, 1958), Lydia Mendoza’s La Gloria de Texas (Arhoolie Records, 1980), Gustavus D. Pike’s The Jubilee Singers, and Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars (Boston and New York, 1873) and riot grrrl zines of the 1990s.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performs at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival. Photo by Diana Jo Davies. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the “Godmother of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” rose to prominence in the 1930s as a pioneer of mixing “secular sounds,” such as electric guitar, with sacred lyrics.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performs at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival. Photo by Diana Jo Davies. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the “Godmother of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” rose to prominence in the 1930s as a pioneer of mixing “secular sounds,” such as electric guitar, with sacred lyrics.

“We are thrilled to present women movers and shakers who forever altered the course of American music,” said Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, director of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. “We honor their drive, their creativity, their advocacy and their achievement, painting a portrait of their long-standing influence through Smithsonian collections.”

From Mother Goose to Girl Power, Prohibition to the civil rights movement, women have made their voices heard in the story of American music. Through rare and unique books, photographs, albums and recordings, “Music HerStory” captures their innovative contributions and courageous spirit.

Support

“Music HerStory” received support from the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative. Special thanks to The Arhoolie Foundation and the DC Public Library.

Programs

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and the Smithsonian’s American Women’s History Initiative co-present “Folkways @ Folklife: Alice Gerrard and Leyla McCalla,” an event in conjunction with the exhibition, Friday, June 24, at 7 p.m. on the Rinzler Stage at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall. Visit the event page for more details.

Additional public programs accompanying the exhibition will engage diverse audiences from K–12 to adult, including workshops, lectures and hands-on sessions.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives at ALA 2022

Will you be in Washington, DC for the American Libraries Association Annual Conference and Exhibition this June? If so, we look forward to meeting you! The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives will offer several opportunities for conference attendees to get to know our services, staff, and collections. Whether it’s during a tour of one of our locations or at a conference session, we hope to connect with you.

Tours

Before and after the conference, we’re offering tours of four of our locations in downtown DC – Smithsonian Institution Archives, American Art/Portrait Gallery Library, the Joseph F. Cullman Library of Natural History, and the National Museum of Natural History Library.

In addition, we’re offering special curator-led visits to our newest exhibition, Music HerStory, which opens June 22nd. This is a great opportunity to learn more about the role of American women in music history with Meredith Holmgren, Curator of American Women’s Music, and see the exhibit without the crowds!

Space for each tour is limited and registration is required. Learn more and sign up here: https://s.si.edu/sla-ala-tours

Conference Sessions and Posters

Several Smithsonian Libraries and Archives staff members will be speaking in sessions, sharing their work and experiences. Check the ALA Conference Scheduler as sessions are updated.

APALA President’s Program: Change in and Barriers to Library Leadership for Asian and Pacific American Library Workers: A Panel Discussion, Saturday, 10 am.

Our anthropology librarian Amanda Landis will participate in this session hosted by the Asian Pacific American Library Association. This panel discussion will center on the voices of AAPI library leaders and their challenges and opportunities in the profession at large, and how to rethink about new opportunities going forward. Based on an IMLS funded project called, “Path to Leadership,” the discussion will focus on the experiences of forum participants and how they envision change in the profession at large and its leadership going forward. This session is co-sponsored by the Chinese American Librarians Association (CALA).

Core President’s Program: Dear Librarians, No more trauma, no more pain: Reclaiming Our Value and Choosing To Win featuring Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty. Saturday, 4 pm.