Rise of the Machines

Technology Comes to Life

The revolution in industrial mechanization that began in the mid-1700's progressed at an astounding pace throughout the 19th century, spurred in part by technological improvements in machining tools, steam engines, and iron forging. "Self-acting" machines, powered by steam or electricity, appeared to move of their own volition, accomplishing tasks once done only by human hands. Artisans and skilled workers were displaced. The factory was here to stay.

Clockwork automatons, entertaining novelties made to look and move like living creatures, had been around for centuries. But this new era of machines were mimicking life in ways only imagined before, and making their presence felt in the home and in the workplace, altering forever how we work and live.

Literary fiction of the time reflected this strange new world, speculating on the future and inventing wonders like steam-powered mechanical men. If machines could work, what more could they accomplish? Where, in this rapidly mechanizing world, would machines take us?

...it was impossible not to invest the machine with some faculty of intellect; it seemed to have made the first step from brute matter to life and purpose, showing its progress by great power.

– Dorothy Wordsworth, from her journal, on first seeing a steam-powered water pump, 1803

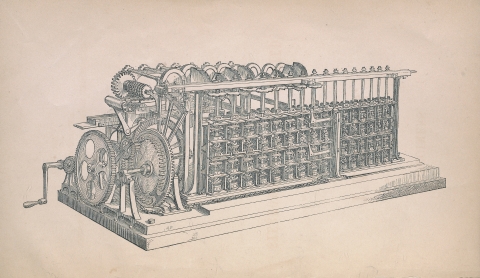

In the 1820s British mathematician and engineer Charles Babbage devised a mechanical calculator known as a difference engine to automatically calculate and print accurate mathematical tables. Essential to tasks like navigation, banking, and engineering, such tables had to be painstakingly verified and were prone to errors made by human “calculators” and typesetters - errors that could lead to significant loss. While not built in his lifetime, Babbage’s inventive design for mechanizing calculation was an important early step toward modern computing.

|

|

National Museum of American History

Gift of International Business Machines Corporation

(Photos: Hugh Talman)

Swedish inventor and printer Georg Scheutz, with his son Edvard, was inspired by Babbage's design and began designing a working difference engine of his own in 1834. Though it was mechanically temperamental, and a more modest scale than Babbage's version, their calculating engine successfully produced the first mathematical tables calculated and printed by machine.

|

|

|

Specimens of Tables, Calculated, Stereomoulded and Printed by Machinery

London, 1857

The mechanical imitation of life had other applications as well. Sir George Cayley, sometimes called the "English Leonardo" due to his wide-ranging achievements in engineering, was an important pioneer in aeronautics and aerial navigation in the early-to-mid 1800's. While best known for his contributions to flight, Cayley turned his engineering talents toward creating an artificial hand for the wounded son of a tenant farmer. He wished to make a more affordable and versatile model, both effective and within the means of victims of industrial and wartime injury. His innovative design mimicked the articulation and control of human movement, and contains features used in modern prostheses.

|

|

“Description of an artificial hand”

Mechanics’ Magazine, March 1845

These technological innovations also found their way into the home. This 1871 patent model is the basis for one of earliest crawling dolls manufactured in America. The clockwork arms and legs simulate crawling while the baby rolls forward on brass wheels. The lifelike automaton, once an elegant mechanical amusement for the upper class, was on its way to becoming a classic childhood toy.

|

Designed by George P. Clarke

National Museum of American History

The limits of machine intelligence in the 19th century didn't stop enterprising efforts to dupe the public. Ajeeb, a mechanical chess-playing automaton, toured the world's entertainment parlors until the late 1800s. Many visitors believed that Ajeeb, and others like it, could be clever enough to outplay human competitors, and that they were witnessing a thinking machine in action. It wasn't so: a human chess-player was concealed inside.

|

|

Trade card from the Eden Musée, New York, 1896

National Museum of American History

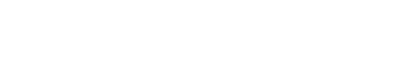

The word robot wouldn't appear until 1920, when Czech writer Karel Čapek coined the word in his play, R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots). Derived from the Czech word robota, meaning “forced labor” or "drudgery," he used it to describe a manufactured humanoid workforce. Decades before Čapek, however, the possibilities of mechanization and steam power were already inspiring mechanical beings in fiction. Steam-powered mechanical men began appearing in inexpensively-produced adventure stories in the late 1860's. The popular tales featured the heroic exploits of an inventor and his fantastic creations.

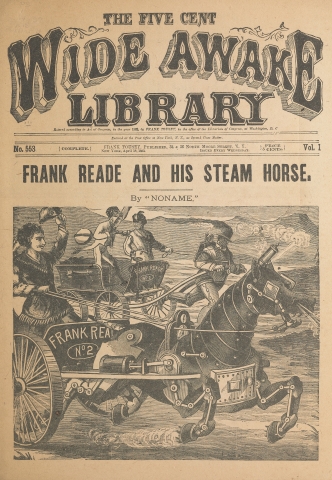

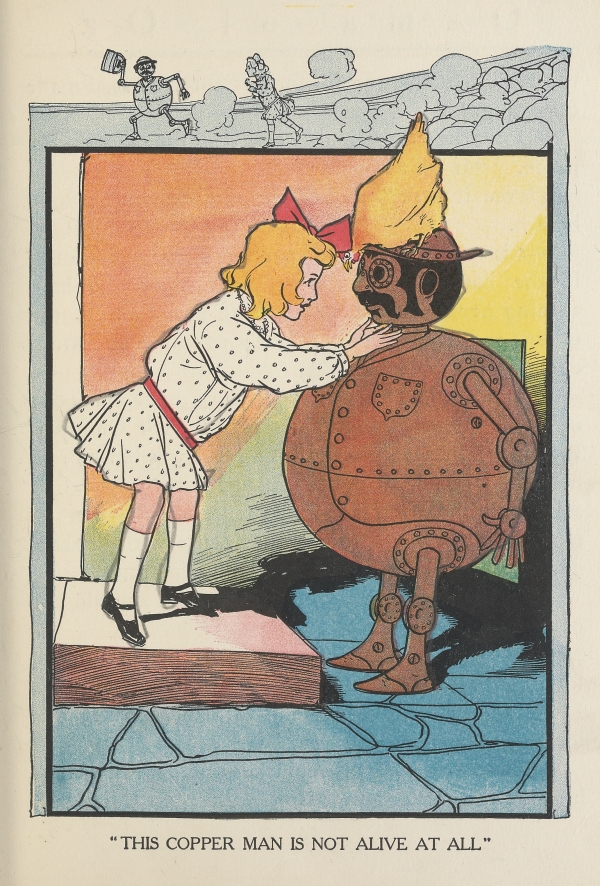

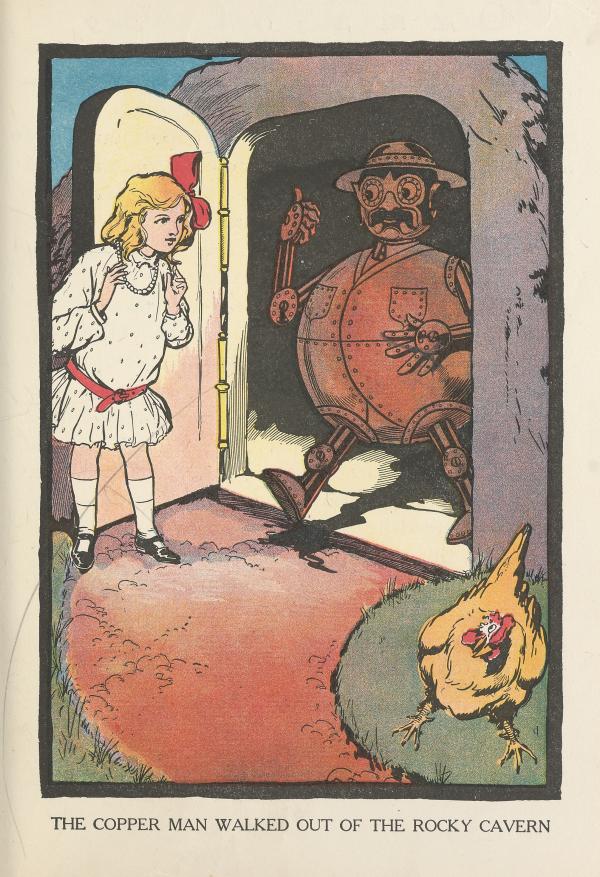

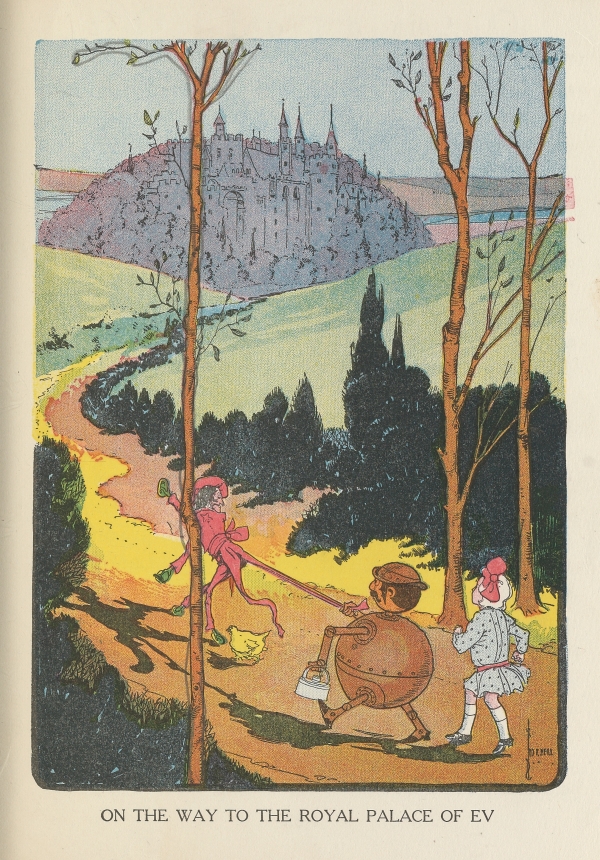

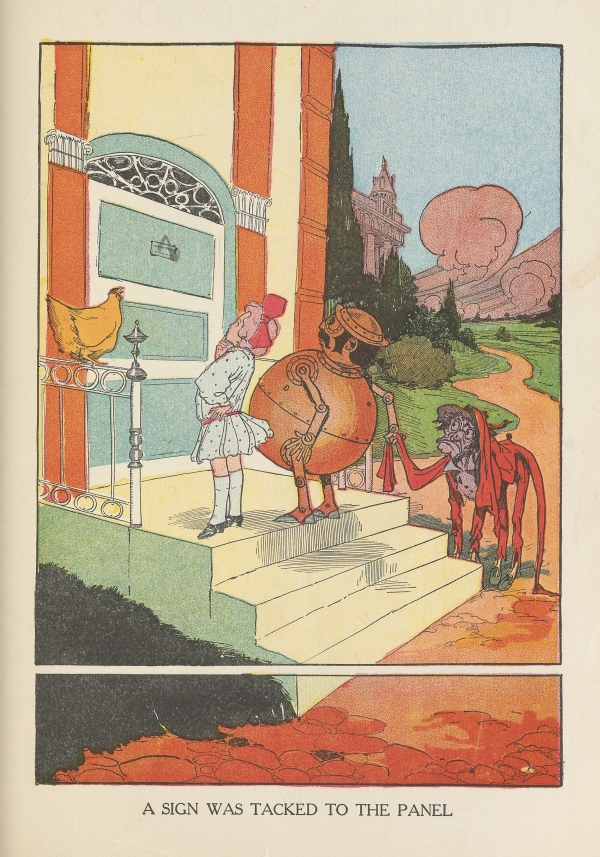

Another precursor to the robot was the copper-clad Tik Tok, the Machine Man, from L. Frank Baum's Oz books. Unlike the better known Tin Woodman of Oz, Tik Tok wasn't alive; he was a mechanical clockwork device. Baum even provided him with a manufacturer’s label and operating instructions: “Smith & Tinker's Patent Double-Action Extra-Responsive MECHANICAL MAN... Thinks, Speaks, Acts and Does Everything But Live.”

L. Frank Baum

Ozma of Oz: A Record of Her Adventures ...

Chicago, 1907.

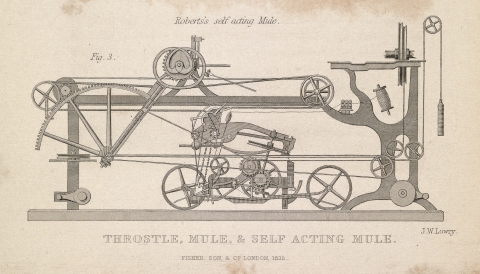

Some of the greatest technological innovations were in the textile industry. Richard Roberts’ steam-powered “self-acting” spinning mule, nicknamed the Iron Man, replaced skilled workers and outperformed them tirelessly. Spinning, once a manual trade performed in homes, was now the job of automated factory machinery. Several machines could be overseen by a single minimally-trained worker. Andrew Ure, a staunch supporter of technological progress in textile manufacture, praised the "Iron Man" as "a machine apparently instinct with the thought, feeling, and tact of the experienced workman."

|

from Sir Edward Baines' History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain

London, 1835

It is the Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word; the age which, with its whole undivided might, forwards, teaches and practises the great art of adapting means to ends. Nothing is now done directly, or by hand; all is by rule and calculated contrivance.

—Thomas Carlyle, "Signs of the Times," The Edinburgh Review, 1829

What an army of servants do the machines thus employ! Are there not probably more men engaged in tending machinery than in tending men? Do not machines eat as it were by mannery? Are we not ourselves creating our successors in the supremacy of the earth? daily adding to the beauty and delicacy of their organisation, daily giving them greater skill and supplying more and more of that self-regulating, self-acting power which will be better than any intellect?

—Samuel Butler, Erewhon, or: Over the Range, 1872