The Body Electric

Inspiring Frankenstein

In the early 1800s the growing sciences of chemistry and electricity offered provocative new tools to help solve an ancient problem: what is the nature of life? The recent experiments of Luigi Galvani hinted at electricity as a life force.

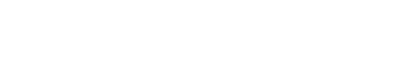

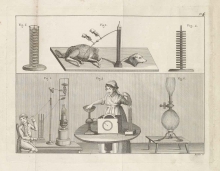

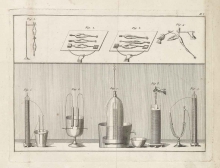

Had Luigi Galvani discovered the spark of life? During an electrical experiment, Italian physician and anatomist Luigi Galvani watched as a scalpel touched a dissected frog on a metal mount — and the frog’s leg kicked. Further experiments led him to theorize that living bodies contain an innate vital force that he called “animal electricity.” In 1791, Galvani published his findings in De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari, and his provocative theory set the world of science abuzz.

De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius

[Commentary on the forces of electricity in muscular motion]

Bologna, 1791

Gift of the Burndy Library

Portait of Alessandro Volta with pile visible at right

Milan, 1827 Gift of the Burndy Library |

Italian physicist Alessandro Volta repeated Galvani’s experiments, but concluded that the two metals alone were responsible for the electric charge, and that certain fluids could conduct electricity. He denied Galvani’s theory of animal electricity and thus began one of science’s most famous disputes (in time, both theories would be proven right). Volta’s findings led him to develop the first battery capable of a continuous electrical current, known as the Voltaic pile, in 1800. Composed of a stack of alternating discs of copper and zinc separated by cardboard soaked in brine, it was a game-changer in the study of electricity and its inventive applications.

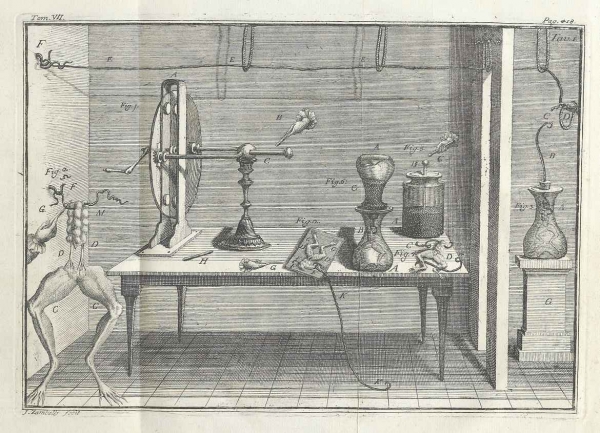

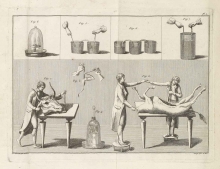

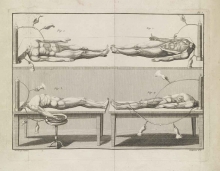

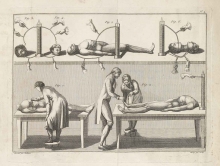

Giovanni Aldini, Galvani’s nephew, defended and built upon his uncle’s controversial theory of animal electricity. In operating theaters crowded with spectators, Aldini conducted sensational electrical experiments throughout Europe, often making use of a Voltaic pile, on the bodies of sheep, dogs, oxen, and even recently executed convicts. With eyes opening and faces grimacing, severed heads appeared to be shocked into life again. Though theatrical and provocative, his experiments were efforts to better understand the workings of electricity in the body, and enable the development of therapeutic galvanic treatments.

To conduct an energetic fluid to the general seat of all impressions; to distribute its influence to the different parts of the nervous and muscular systems; to continue, revive, and, if I may be allowed the expression, to command the vital powers; such are the objects of my researches, and such the advantages which I propose to derive from the action of Galvanism.

—Giovanni Aldini, An account of the late improvements in galvanism, 1804

Aldini's most famous demonstration was on the recently hanged body of convict George Forster at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. The dramatic results shocked spectators, convincing some they were witnessing a dead man come to life. The vivid descriptions of the scene in popular newspapers made an impression on the public. Could the dead be brought back to life?

Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme

[Theoretical and experimental essay on galvanism]

Paris, 1804

39088003171683_0419_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0423_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0427.jpg

39088003171683_0431_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0435_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0439_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0443_crop.jpg

39088003171683_0455_crop.jpg

39088006768360_007_crop.jpg

39088006768360_085_crop.jpg

39088006768360_128_crop.jpg

39088006768360_207_crop_p189.jpg

Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme

[Theoretical and experimental essay on galvanism]

Paris, 1804

Medical practitioners wasted no time embracing this developing science, and treatments based on galvanism were widely touted as cure-alls. American physician Elisha Perkins, for one, claimed that his “tractors,” a pair of iron and brass rods, each less than three inches in length, could cure a range of ailments by drawing extra “electrical fluid” from the body. Many were skeptical, and decried Perkins as an opportunist and a quack, so much so that, while in London, Perkins’ son, a bookseller, enlisted writer Thomas Fessenden to write a satirical poem lampooning the naysayers. The tractors enjoyed both popularity and ridicule for a brief period, on both sides of the Atlantic.

With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning... when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.

—Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus, 1818

Portrait of Erasmus Darwin

London, 1807 Gift of the Burndy Library |

Shelley cites Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, as an influence on her tale. He is mentioned explicitly both in her introduction to the 1831 edition as well as in the preface to the first edition, written for her by her husband. A famed physician who penned book-length, heavily footnoted poems on a wide array of scientific subjects, Darwin was one of the best known intellectuals of his day, noted for his early thoughts on evolution and other scientific speculations, including the reanimation of dead microorganisms.

templenatureori00darw_0042.jpg

templenatureori00darw_0043.jpg

templenatureori00darw_0064.jpg

templenatureori00darw_0065.jpg

The Temple of Nature, or, The Origin of Society: A Poem, with Philosophical Notes...

Baltimore, 1804

Gift of the Burndy Library

The composition of the atmosphere, and the properties of the gases, have been ascertained; the phenomena of electricity have been developed; the lightnings have been taken from the clouds; and, lastly, a new influence has been discovered, which has enabled man to produce from combinations of dead matter effects which were formerly occasioned only by animal organs.

—Humphry Davy, Discourse, introductory to a course of lectures on chemistry, 1802