Terra Incognita

Adventure and Exploration: To the Far Reaches of the World

Exploration to unknown lands provided the opportunity to learn about the natural world. Lured by commerce, empire, national pride, or scientific curiosity, travelers made countless scientific observations and returned with reports about little-known peoples, places, plants, and animals.

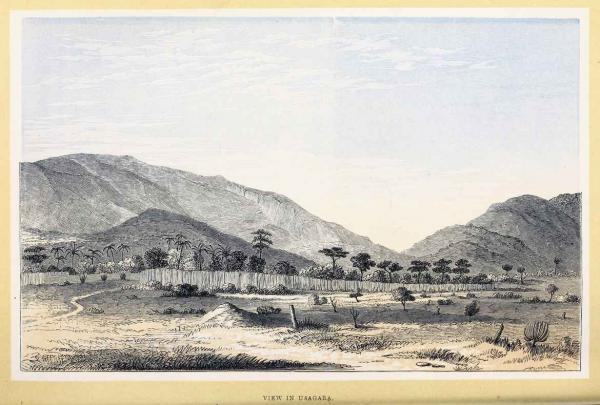

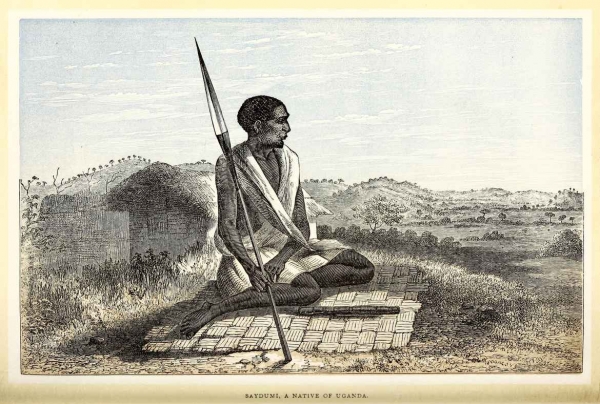

By the mid-1800s, the polar regions and the interior of Africa were among the last parts of the globe to be seen and mapped by Western explorers. These remote locales became fixtures of popular culture, as armchair travelers read about perilous adventures in these new and unfamiliar worlds. Novelists adapted true-life narratives to their fictions and spun imaginative tales of adventure in unknown lands.

Regions unknown! My imagination could depict to itself there worthy, adventurous, and devoted men, nibbling at the edges, ...conquering a bit of truth here and a bit of truth there, and sometimes swallowed up by the mystery their hearts were so persistently set on unveiling.

—Joseph Conrad, Geography and Some Explorers

Arctic Voyages

The general atlas for Carey's edition of Guthrie's Geography improved.

Philadelphia, 1795

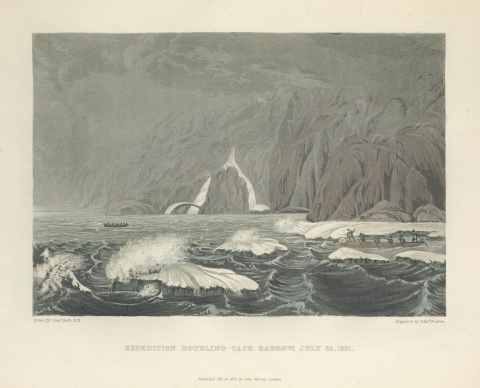

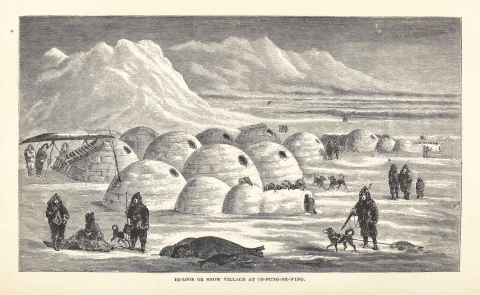

British explorer Sir John Franklin was one of many Arctic explorers seeking a Northwest Passage, a northern sailing route that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, opening a new avenue for trade. His first expedition to the Arctic (1819–1822) ended badly — 11 of the 20 men in his party died — but the public still viewed him as a hero. Franklin’s narrative of the journey, published in London in 1823, mixed adventure and discovery with science, attracting public and scholarly audiences alike.

|

|

Narrative of a Journey to the Shores Polar Sea...

London, 1823

Portrait of Elisha Kent Kane by unknown photographer Ambrotype, ca. 1855 Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

|

Franklin’s fourth and final voyage, however, an 1845 attempt to map a stretch of the Northwest Passage, ended in disaster. The two ships, the Erebus and Terror, became ice-bound, stranding the crew, leading to starvation and death from extreme cold, lead poisoning and disease. Rumors of cannibalism circulated.

The story was a sensation in Britain and America. Lady Jane Franklin, the explorer’s widow, sponsored numerous expeditions and was an active driver of the public’s interest in solving the mystery of the lost journey, fueling the far-fetched hope of finding survivors. A considerable reward was offered, prompting numerous searches, over both land and sea.

Elisha Kent Kane, a Philadelphia surgeon, served as medical officer on the first American expedition in search of Franklin (1850–1851), financed by American merchant Henry Grinnell. While little was learned of the fate of the lost Franklin expedition on the journey, Kane’s gripping and colorful narrative made him a popular heroic figure.

Kane earned respect and fame from both the scientific community and the public. He died far from home, in Cuba, at age 36. As his body traveled from New Orleans home to Philadelphia, crowds gathered to honor him along the way.

...the last of the Danish settlements. It is the jumping-off place of Arctic navigators – our last point of communication with the outside world. Here the British explorers put the date to their official reports, and send home their last letters of good-bye.

—Elisha Kent Kane, The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of

Sir John Franklin. A Personal Narrative, 1854

Other novelists also saw the imaginative possibilities of Arctic adventures. The Frank Reade Weekly Magazine, a series of cheap and colorful dime novels aimed at a young, predominantly male audience. Popular with the growing literate middle class, they spun tales of adventure in exotic settings – often in polar regions—with the inventor hero traveling in futuristic airships and submarines. Author Thomas Wallace Knox, having traveled the world, wrote a series of adventure novels, also aimed at young boys. His The Voyage of the Vivian details both the Franklin expedition and the theory of an Open Polar Sea. Additionally, Gordon Stables, a Scottish naval physician, used his experience on whaling ships to bring realism to his sailing adventure stories, choosing the compelling Arctic as the setting for many fictional exploits.

|

Commander Cheyne and Odoardi Barry |

Interest in all things Arctic also found its way into parlors and music halls in the form of popular songs. Among them was “Northward, Ho! or, Baffled, Not Beaten,” with lyrics penned by John P. Cheyne, a British naval officer and veteran of three expeditions in search of Franklin. He hoped his song would drum up popular support for his unconventional (and unsuccessful) idea to use manned balloons to reach the North Pole.

In about 1850, broadsides with the lyrics to another song began to circulate, testimony to the impact the story of the lost Franklin expedition had on the public. “Lady Franklin’s Lament,” often sung to the tune of a traditional Irish ballad, recounts the tragedy from the point of view of a sailor aboard ship who dreams of Lady Franklin mourning her husband’s disappearance.

In Baffin's Bay where the whale fish blow

The fate of Franklin no man may know

The fate of Franklin no tongue can tell

Lord Franklin alone with his sailors do dwell

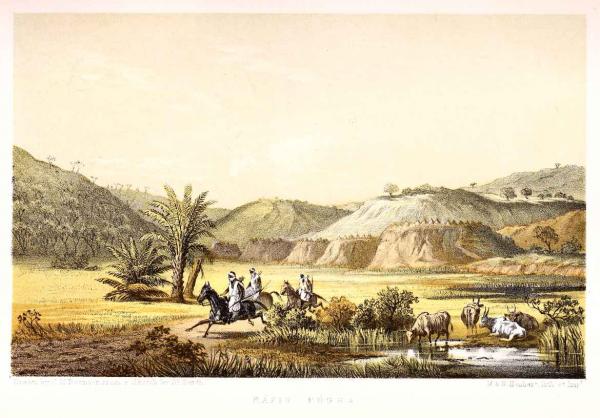

African Exploration

Expeditions to Africa — with its wide expanse and varied cultures, unfamiliar to Western eyes—made for equally compelling tales. The public was transfixed by illustrated magazines with the latest news of adventurers in exotic locales. Though risks were certainly involved in these expeditions, Africa was sensationalized in the press, depicted as mysterious and fraught with danger, further piquing the interest of folks back home.

Map of Africa from Cary's New Universal Atlas

London, 1808

Perhaps the most widely recognized African explorer in his day, Dr. David Livingstone went to Africa to put his medical expertise to use, spread Christianity, and bring awareness of the slave trade to the public. Livingstone was a hero to many in Britain, and detailed accounts of his life and adventures were reported in magazines and newspapers. His extensive travels greatly improved geographical knowledge of southern and central Africa. His popularity at home was immense; his Missionary Travels sold more than 70,000 copies within a few months of publication.

|

|

Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa: Including

a Sketch of Sixteen Years' Residence in the Interior of Africa ...

London, 1857

Russell E. Train Africana Collection

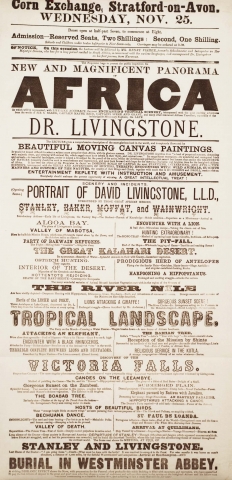

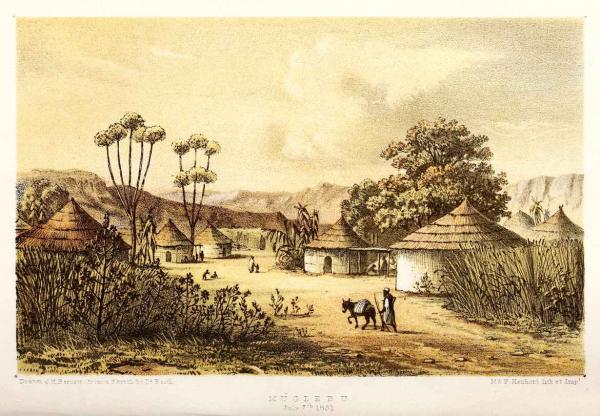

An increasingly curious public sought out ways other than books and newspapers to feed their interest in these distant lands and their celebrity explorers. Panoramas, large-scale paintings in the round, were the IMAX movies of the time. Audiences enjoyed the immersive and thrilling illusion of visiting far-off places. New developments in photographic printing helped spur interest in magic lantern shows. These were extremely popular forms of entertainment and education, featuring glass slides with printed, hand-painted, or photographically reproduced images viewed through a kind of projector.

|

David Broadside advertisement

Stratford-upon-Avon, after 1873 Russell E. Train Africana Collection |

Glass magic lantern slides

The Life and Work of David Livingstone London, ca. 1900 Russell E. Train Africana Collection |

|

Heinrich Barth Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa New York, 1857–1858 Russell E. Train Africana Collection |

Richard Francis Burton The Lake Regions of Central Africa: A Picture of Exploration London, 1860 Russell E. Train Africana Collection |

Verne looked to these expeditions for inspiration for his novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon; Voyage of Discovery in Africa, by Three Englishmen, first published in Paris in 1863, and the first book issued with French publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. With this work, Verne establishes his formula for the successful tales to come, merging risk and adventure with a wealth of technical and historical detail. The book touches on important contemporary issues, like the slave trade and race, and describes recent efforts to map the interior. His fictional heroes trace the paths taken by the real-life explorers, seeking “their point of intersection, which no traveler has yet been able to reach... the very heart of Africa,” while crossing the continent in a balloon outfitted with Verne’s imaginary technological improvements.

![Jules Verne, Cinq semaines en ballon; voyage de découvertes en Afrique, par trois anglais [Five weeks in a balloon; voyage of discovery in Africa, by three Englishmen] Paris, 1867, Gift of the Burndy Library.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/fantastic-worlds-verne-0006.jpg)

|

![Jules Verne, Cinq semaines en ballon; voyage de découvertes en Afrique, par trois anglais [Five weeks in a balloon; voyage of discovery in Africa, by three Englishmen] Paris, 1867, Gift of the Burndy Library.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/fantastic-worlds-verne-0009.jpg)

|

![Jules Verne, Cinq semaines en ballon; voyage de découvertes en Afrique, par trois anglais [Five weeks in a balloon; voyage of discovery in Africa, by three Englishmen] Paris, 1867, Gift of the Burndy Library.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/fantastic-worlds-verne-0106.jpg)

|

Cinq semaines en ballon; voyage de découvertes en Afrique, par trois anglais

[Five weeks in a balloon; voyage of discovery in Africa, by three Englishmen]

Paris, 1867

Gift of the Burndy Library

Africa is, at length, about to surrender the secret of her vast solitudes; a modern Oedipus is to give us the key to that enigma which the learned men of sixty centuries have not been able to decipher.

—Jules Verne, Five weeks in a balloon

|

H. Rider Haggard

King Solomon’s Mines London, 1885 Courtesy of Jane and Howard Frank |

An instant best-seller, H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines was the first English novel set in Africa and was an influential early example of the popular “Lost World” genre of science fiction. Following an ancient map drawn, in his own blood, by a 16th century Portuguese explorer, the heroes seek the fabled mines and in the process discover an unknown society cut off from the rest of the world. Haggard had lived in British colonial South Africa and modeled his hero Allan Quartermain after famous big game hunter Frederick Courtney Selous. Recent discoveries of the ruins of ancient civilizations, like Great Zimbabwe in southern Africa, and Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, helped inspired the plot, and established a new genre of fiction.

By the end of the 19th century, the interest in scientific discovery in Africa waned, as explorations of the interior, missionary efforts, and commercial interests led to the occupation of African lands by European powers competing for colonial territories. But the allure of Africa’s landscapes and cultures had left its imprint on the world of fiction.

![Jules Verne, Voyages et Aventures du Capitaine Hatteras [Travels and adventures of Captain Hatteras], Paris, 1867, Courtesy of Jane and Howard Frank](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/1_g1-1_frank_verne_hatteras_001_crop.jpg?itok=WzPiV174)