Libraries' Blog

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles: National Library Week 2022

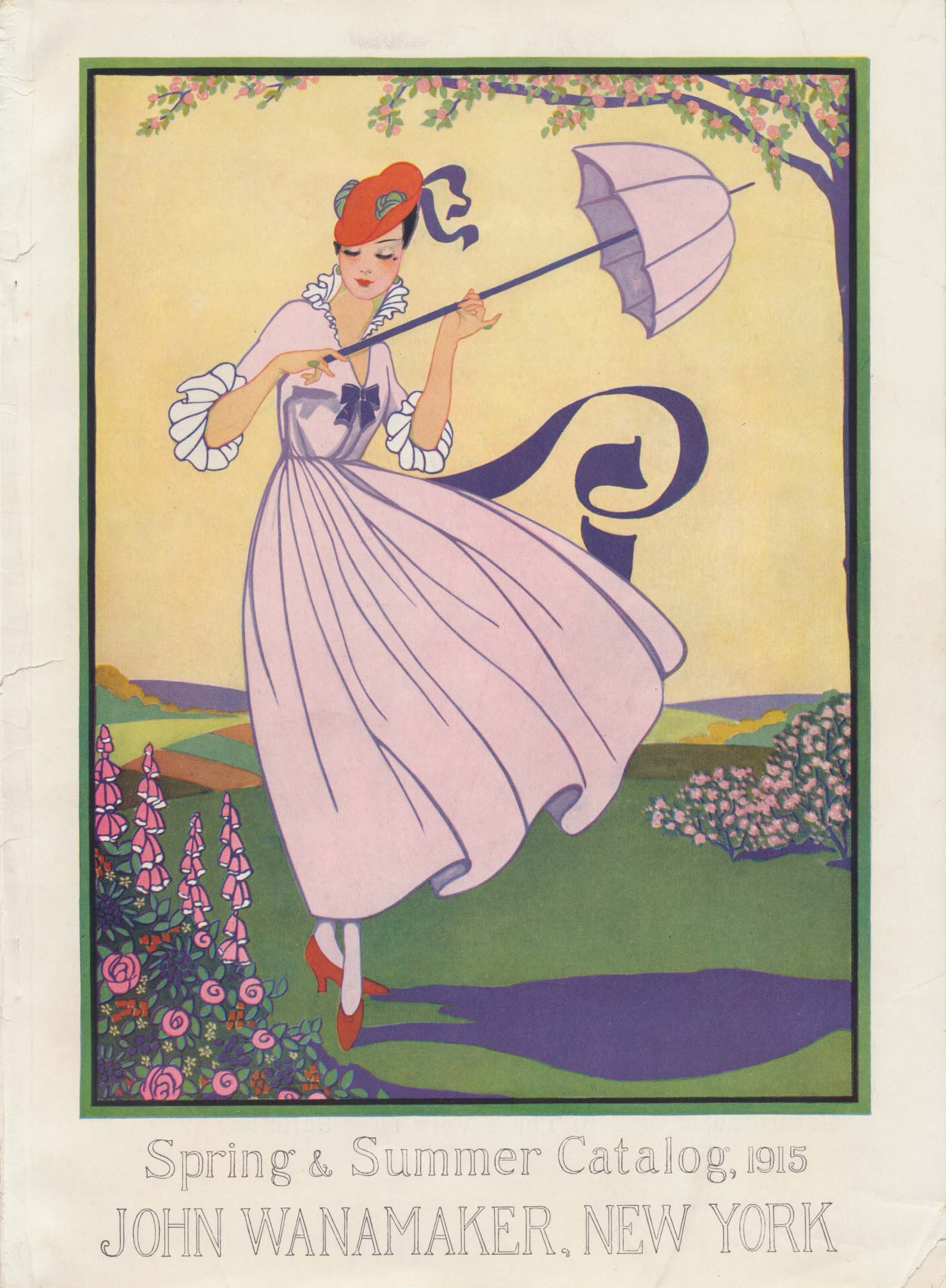

To celebrate National Library Week and a new spring season, we’ve put together another round of digital jigsaw puzzles. This time we’re featuring a variety of soothing natural history-related scenes.

Play them right here on our blog or use the links to play full screen. Each puzzle is set at about 100 pieces but they are customizable to any skill set. Click the grid icon in the center to adjust the number of pieces. For this batch, all of the images are freely available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, a consortium effort to digitize biodiversity literature, based at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

Miss our previous puzzles? Find them here.

“Sea Dragons”, Marvels of the Universe (1911).

Marvels of the universe: a popular work on the marvels of the heavens, the earth, plant life, animal life, the mighty deep was first published by Hutchinson and Company as a periodical between 1911-1912 “in about 24 fortnightly parts”. These Sea Dragons were noted as “Painted by Seppings Wright.”

Play online: https://jigex.com/joCHo

“Sea Dragons”, Marvels of the Universe (1911).

“Sea Dragons”, Marvels of the Universe (1911).

Jigsaw Puzzle

“Erycynids”, Animate Creation (1885).

Animate Creation is an adaptation of Reverend John George Wood’s natural history publication Our Living World. This version, published in 60 parts by S. Hess, was specifically revised for an American audience and incorporated material from several sources, including the Smithsonian’s Spencer F. Baird and Robert Ridgway. This plate of butterflies was likely reproduced from a lithograph by L. Prang & Co.

Play online: https://jigex.com/nXFZn

“Erycynids”, Animate Creation (1885).

“Erycynids”, Animate Creation (1885).

Jigsaw Puzzle

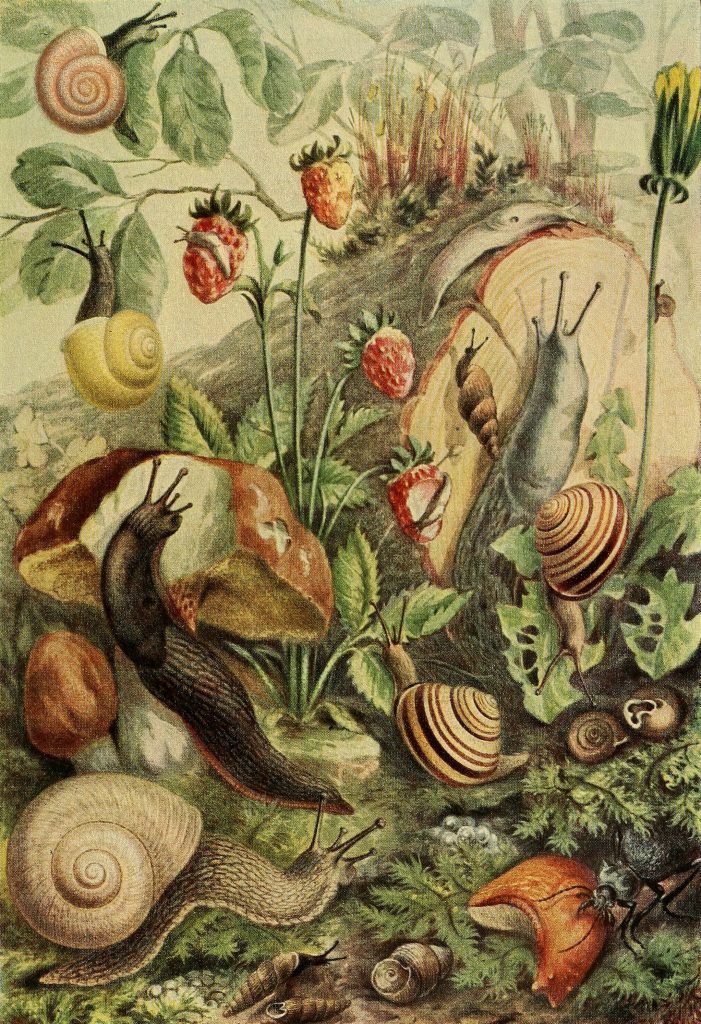

“Landschnecken”, Brehms Tierleben (1876-1879).

Brehms Tierleben is a zoological encyclopedia first published in the 1860s. Alfred Edmund Brehm (1829–1884) was a German zoologist who commonly wrote articles for popular scientific magazines. Brehm was commissioned to produce a 10-volume encyclopedia, which was published by the Bibliographisches Institut from 1864-69. This second edition included new illustrations by Gustav Mützel, the brothers August and Friedrich Specht and others.

Play online: https://jigex.com/HJmoG

“Landschnecken”, Brehms Tierleben (1876-1879).

“Landschnecken”, Brehms Tierleben (1876-1879).

Jigsaw Puzzle

“Sea Anemones”, The World of the Sea [1869].

The World of the Sea [1869] is an English translation by Rev. H. Martyn Hart of Alfred Moquin-Tandon’s Le Mon de le Mer. This particular copy was owned by Smithsonian Curator of Mollusks William Healey Dall.

Play online: https://jigex.com/aRFwE

“Sea Anemones”, The World of the Sea [1869].Jigsaw Puzzle

“Sea Anemones”, The World of the Sea [1869].Jigsaw Puzzle

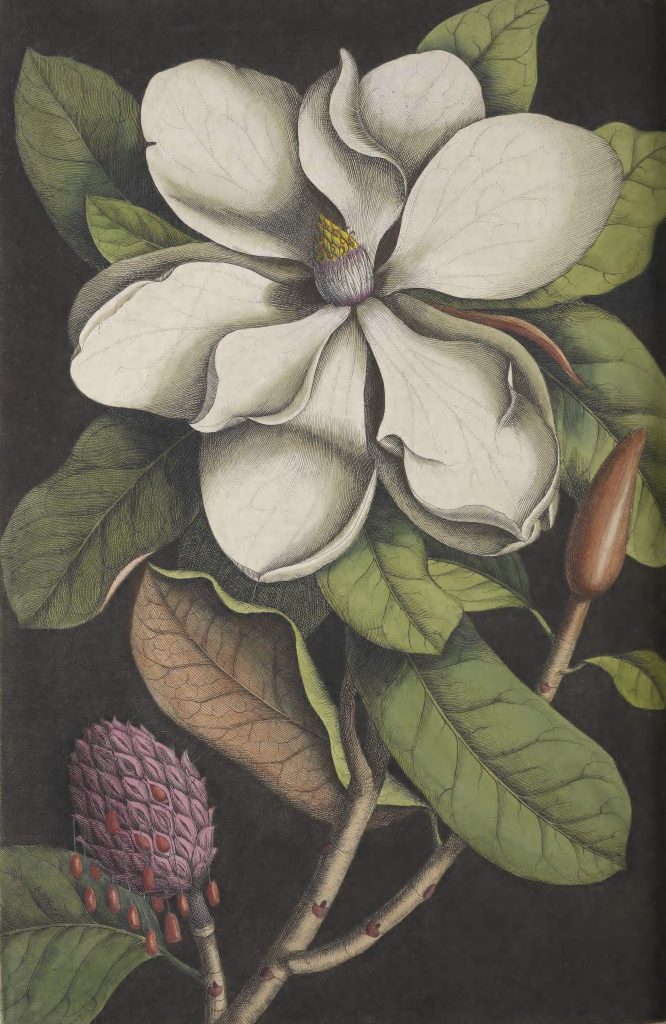

“The Laurel Tree of Carolina”, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1734-1747).

Mark Catesby’s 1729-47 work “The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands” is the first major illustrated publication on the flora and fauna of North America. The work contains 220 plates painted, etched, and hand-colored by Catesby himself. It was published in eleven parts and was one of the most expensive publications of the eighteenth century.

Play online: https://jigex.com/3iSKJ

“The Laurel Tree of Carolina”, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1734-1747).

“The Laurel Tree of Carolina”, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1734-1747).

Jigsaw Puzzle

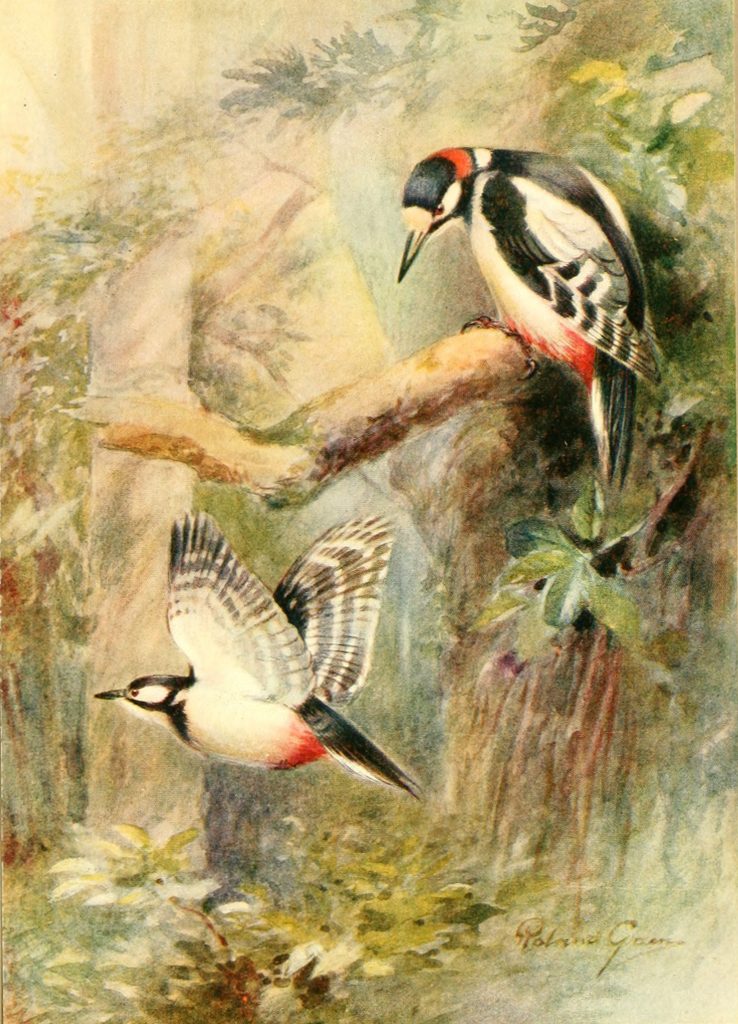

“Great Spotted Woodpeckers”, Birds in flight (1922).

British bird artist Roland Green contributed the illustrations to “Birds in Flight” (1922), including this pair of woodpeckers. The book was written by William Plane Pycraft, an ornithologist and comparative anatomist who worked for decades in the Zoological Department of the British Museum.

Play online: https://jigex.com/3fZv2

“Great Spotted Woodpeckers”, Birds in flight (1922).

“Great Spotted Woodpeckers”, Birds in flight (1922).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Sea slug illustration, Notes and description of specimens collected on the Philippine Expedition of the Steamer Albatross, circa 1908.

This colorful nudibranch is the work of artist Kumataro Ito. Ito accompanied Paul Bartsch, an assistant curator of the Smithsonian’s division of mollusks, when he set sail aboard the USS Albatross on a trip throughout the Philippines in 1907.

Play online: https://jigex.com/EHoSf

Sea slug illustration, Notes and description of specimens collected on the Philippine Expedition of the Steamer Albatross, circa 1908.

Sea slug illustration, Notes and description of specimens collected on the Philippine Expedition of the Steamer Albatross, circa 1908.

Jigsaw Puzzle

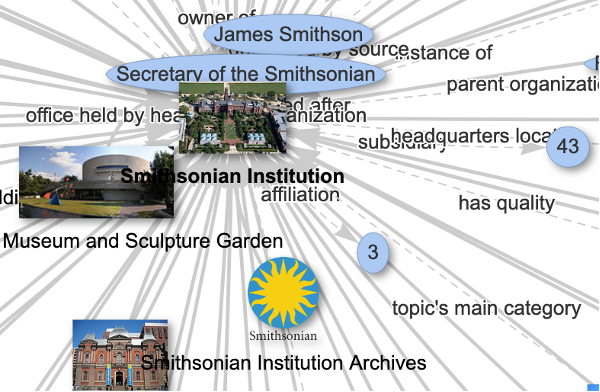

Book Pockets and Date Guides: The Intricacies of a Paper-Based Library System

Before we had online circulation systems, barcodes on books, and automated due date reminders, libraries used paper-based systems for everyday tasks. This required book cards, book pockets, charging trays, and the “ca-chunk” sound of a library date stamp.

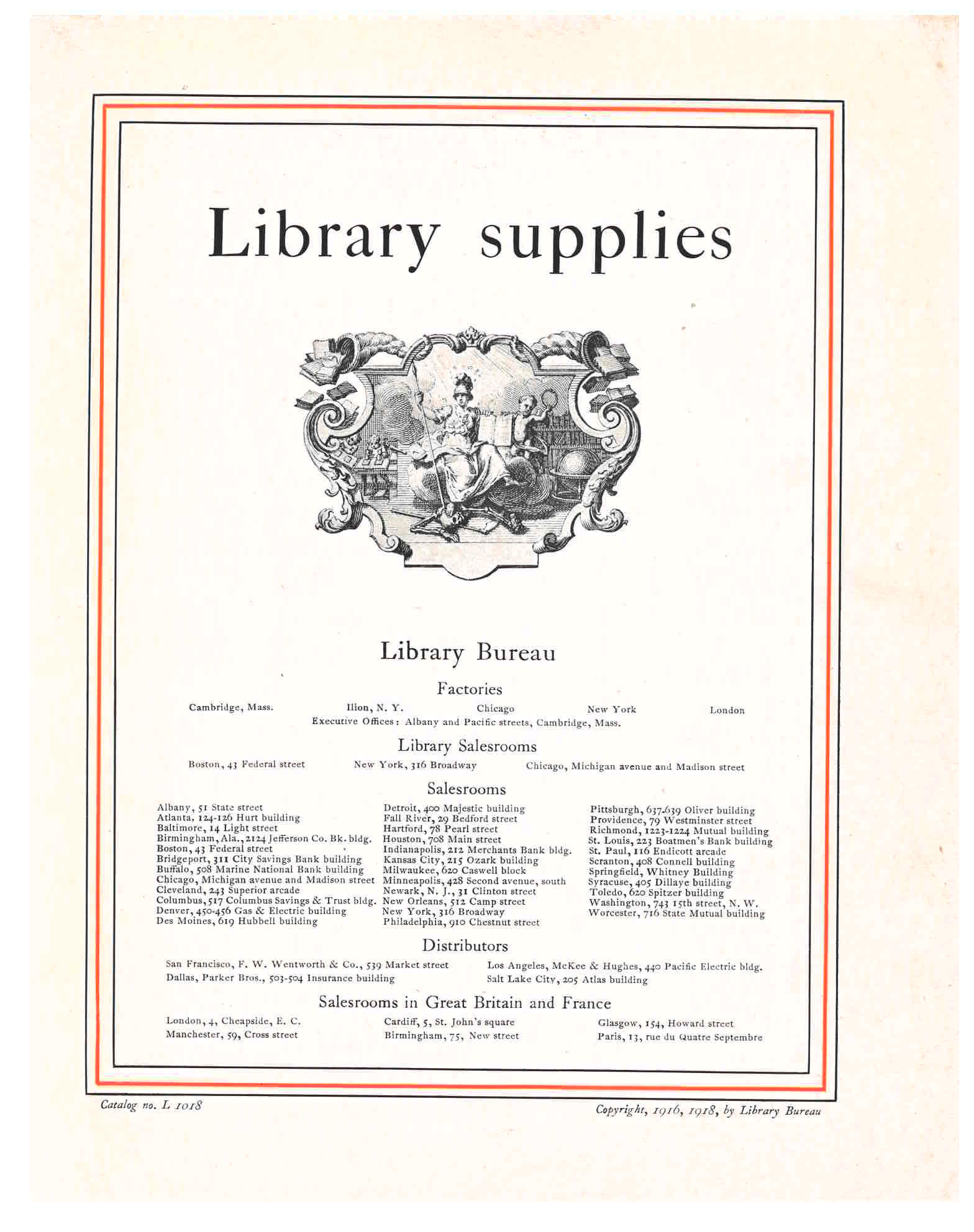

The Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library holds a variety of Library Bureau catalogs. These trade catalogs illustrate everything from large pieces of furniture, such as card catalogs and shelving, to smaller supplies, like book cards and date stamps. One of these is titled Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918) by Library Bureau.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), title page.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), title page.

Just like today, early 20th century libraries recognized the importance of an accurate and quick method for tracking borrowed materials. As this trade catalog states on page 17, “The system should be so simple in operation that the business at the charging desk may be transacted rapidly, in order to avoid undue detention of borrowers and the accumulation of crowds during the busy hours of the day.”

Library staff often multi-task. Among other duties, they handle questions, concerns, and needs of several library users while also discharging and charging books. The Browne System, which is described on the page below, appears to take that into account. It includes a suggestion for temporarily checking-out a book so the library user does not have to wait while the full process is completed.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 19, explanation of the “Plan of Use” for Browne System and L. B. Simplified charging system.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 19, explanation of the “Plan of Use” for Browne System and L. B. Simplified charging system.

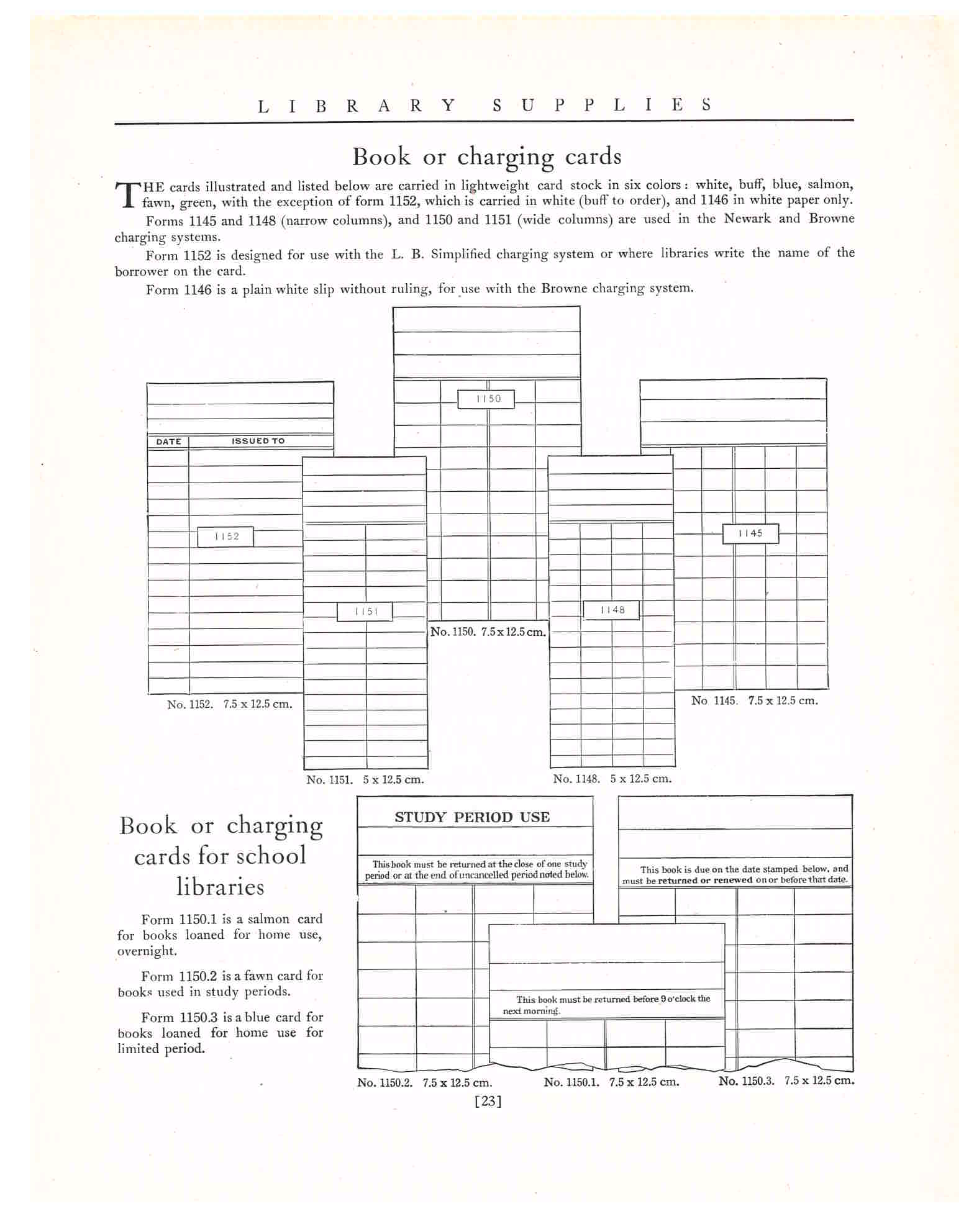

So how did the Browne System work? It required that every book had a book card. The book card included bibliographic information, such as title, author, and call number. This information was typically noted at the top of the card, as shown in the illustration below. Depending on the style, book cards were available in six colors, including white, buff, blue, salmon, fawn, or green.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 23, book or charging cards.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 23, book or charging cards.

The book card was inserted into a book pocket which was pasted inside the back cover of the book. As illustrated below, book pockets came in a variety of designs and sizes. If desired, a library could choose to have their rules and regulations printed on the book pocket. This provided a convenient way to remind borrowers of their responsibilities and share rules of the library, such as limits on number of borrowed books, renewals, and overdue fines.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 24, book or card pockets.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 24, book or card pockets.

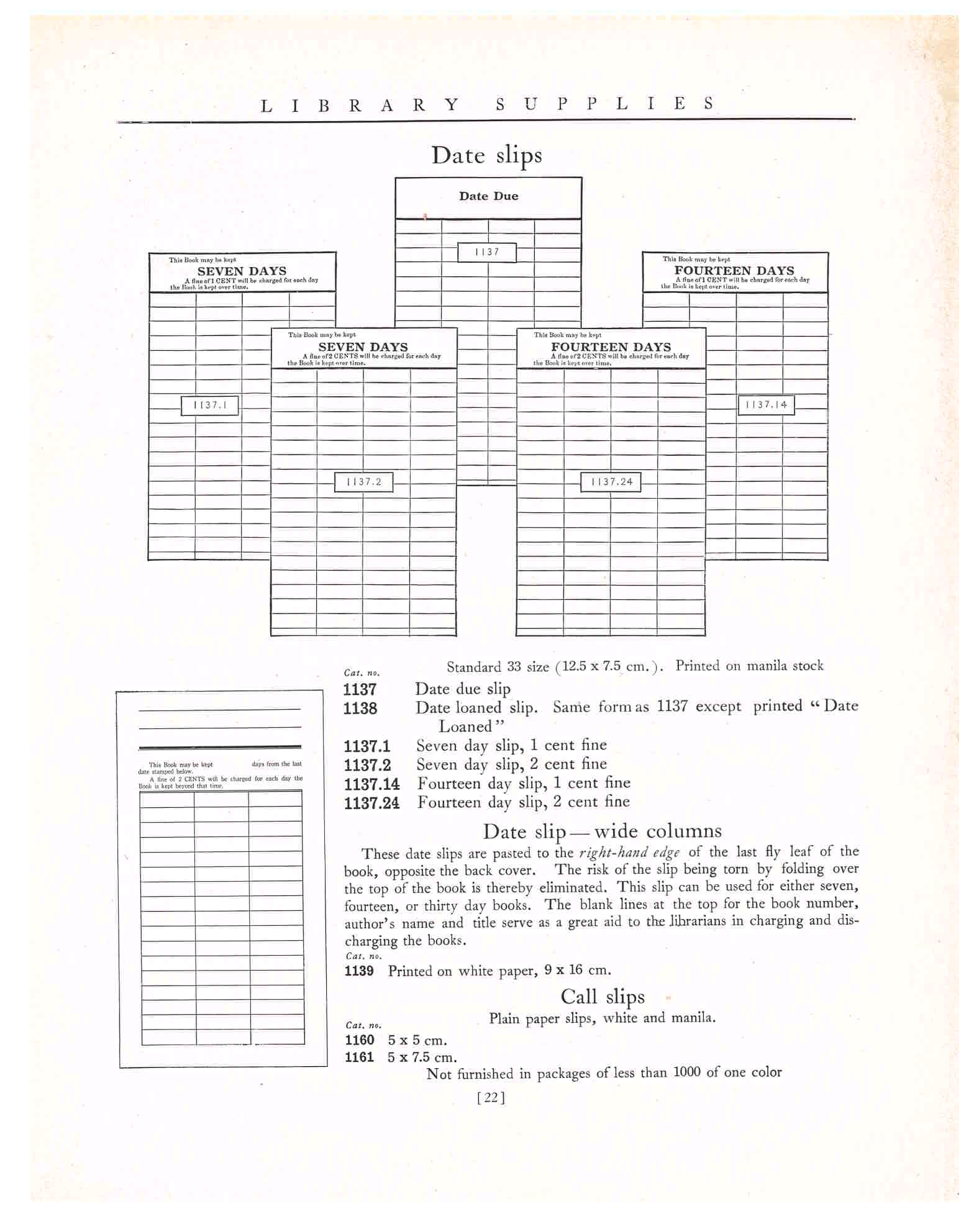

In addition, some libraries might have pasted a separate date slip inside the book for stamping due dates. Some date slips included information about overdue fines. The date slip, shown below (bottom left), includes space for the title, author, and call number followed by boxes for stamping due dates. According to the catalog, this date slip should be pasted to the “right-hand edge of the last fly leaf of the book, opposite the back cover.”

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 22, date slips.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 22, date slips.

When a library user wished to check-out a book, library staff removed the book card from its book pocket and placed it inside the borrower’s pocket. Examples of borrower’s pockets with spaces for borrower’s number, name, and address are shown below. The borrower’s pocket held book cards of all books, arranged numerically by call number, currently checked out to that user. The due date for the book was stamped on either the book pocket or the separate date slip inside the book to remind the user when it was due.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 25, book or card pockets that can be used as borrower’s pockets.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 25, book or card pockets that can be used as borrower’s pockets.

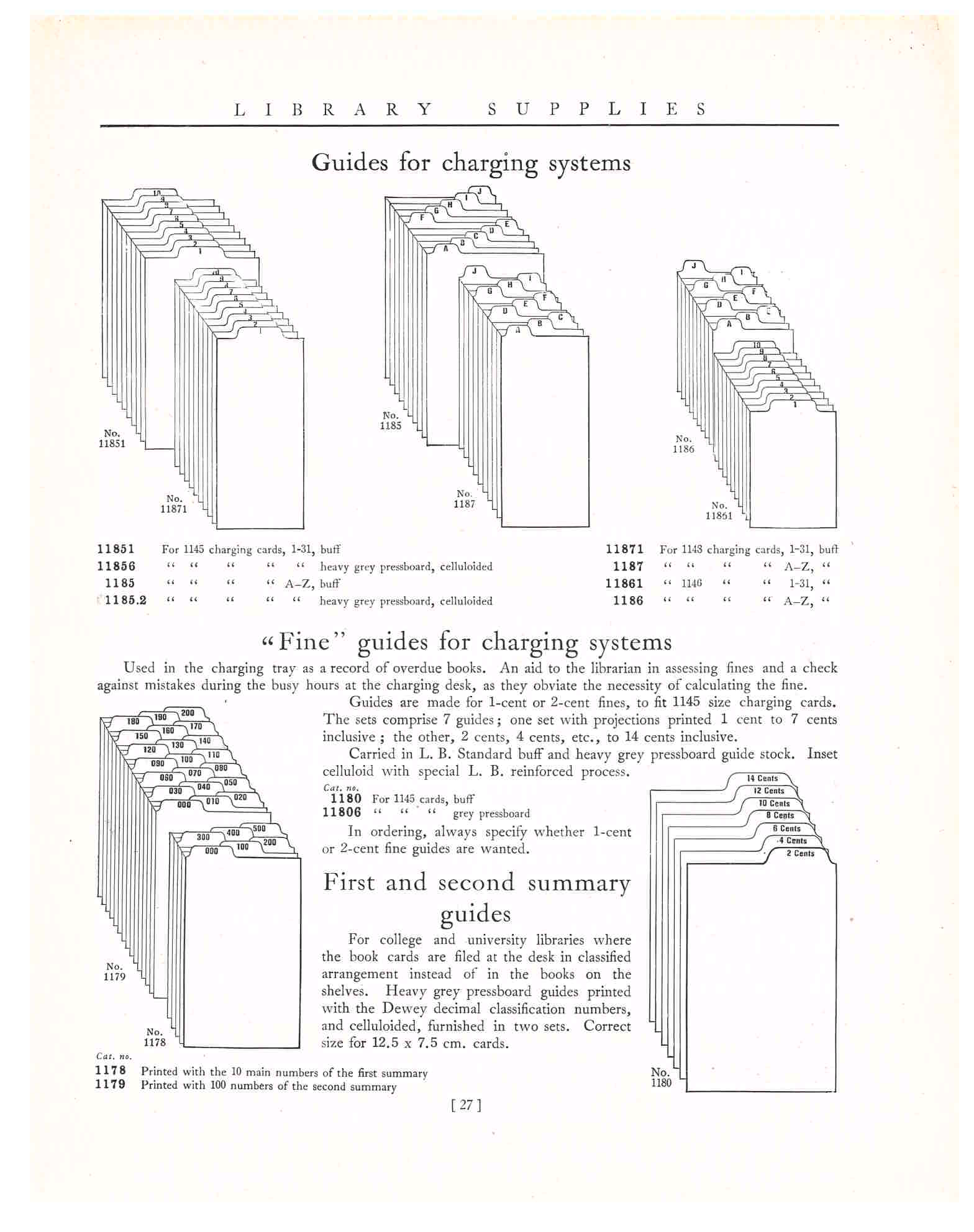

The borrower’s pocket was placed in a charging tray behind a date guide corresponding to the due date of the book(s). The library had the option of also stamping the due date on the book card, but that was not necessary if the borrower’s pocket was placed behind the correct date guide. Various styles of guides for charging systems are illustrated below, including numerical guides for tracking due dates and alphabetical guides for filing unused borrower’s pockets.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 27, guides for charging systems.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 27, guides for charging systems.

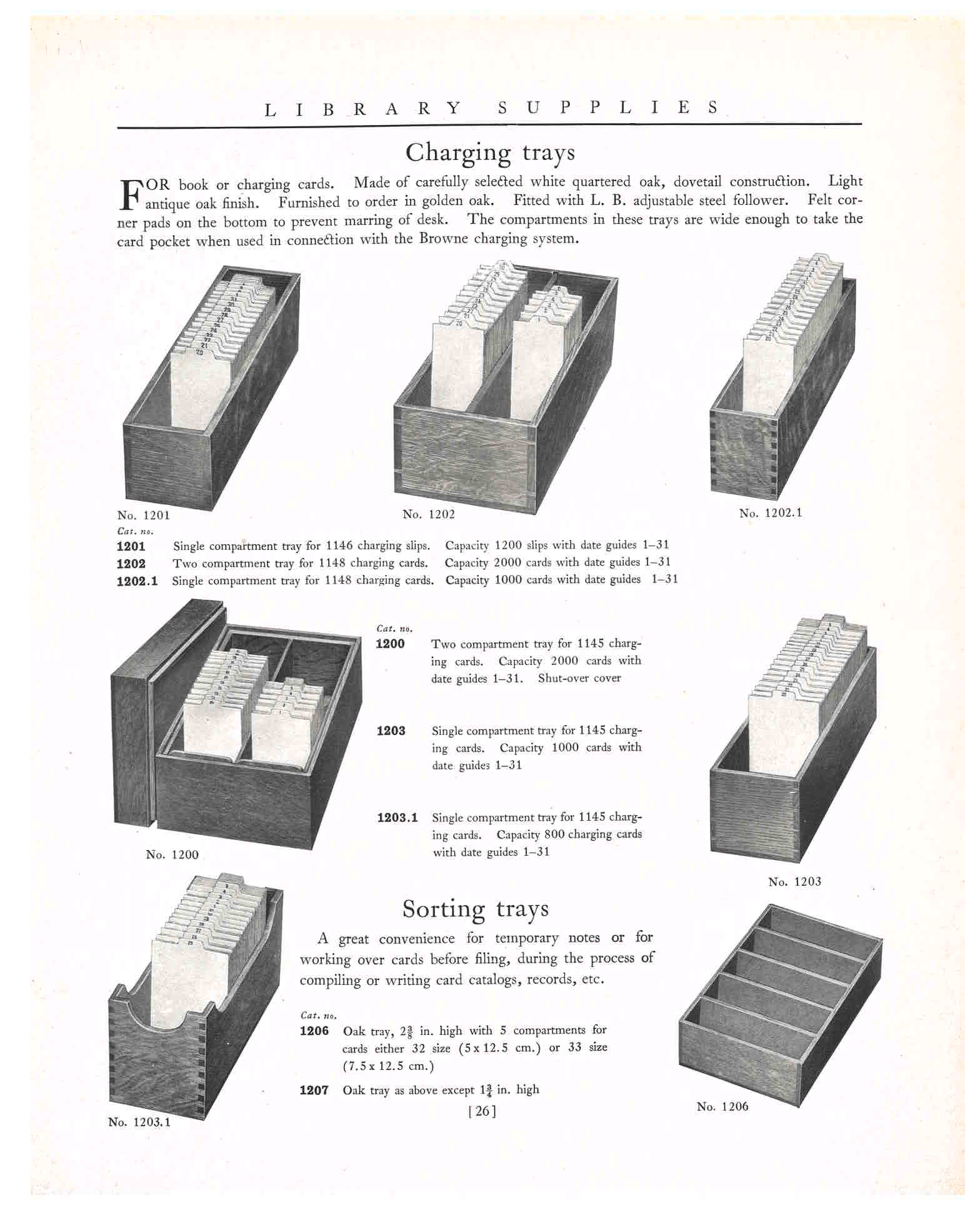

When a book was returned, library staff referred to the due date stamped on the book pocket or date slip of the book. They retrieved the borrower’s pocket from behind that date in the charging tray. Next, the book card was removed from the borrower’s pocket and inserted into the book pocket of the returned book. At this point, the book was checked-in and ready to re-shelve. The borrower’s pocket was filed in alphabetical order in a tray to make it available the next time the user wished to borrow a book.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 26, charging trays and sorting trays with numerical and alphabetical guides.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), page 26, charging trays and sorting trays with numerical and alphabetical guides.

But what if a user returned a book and immediately wanted to check-out another book? The returned book might not have been checked-in yet. Being mindful of the user’s time, staff had an option to temporarily check-out a book.

The Browne System suggested removing the book card from the book pocket of the book the patron wanted to check-out and placing it inside the returned book. This provided a temporary check-out. Later, as time allowed, the check-in process of the returned book was completed by removing the book card from the borrower’s pocket and placing it in the pocket of the returned book.

To complete the check-out of the other book, the book card was removed from the returned book, inserted into the borrower’s pocket, and filed in the charging tray behind the correct due date. This way, the user did not have to wait while the full process was completed.

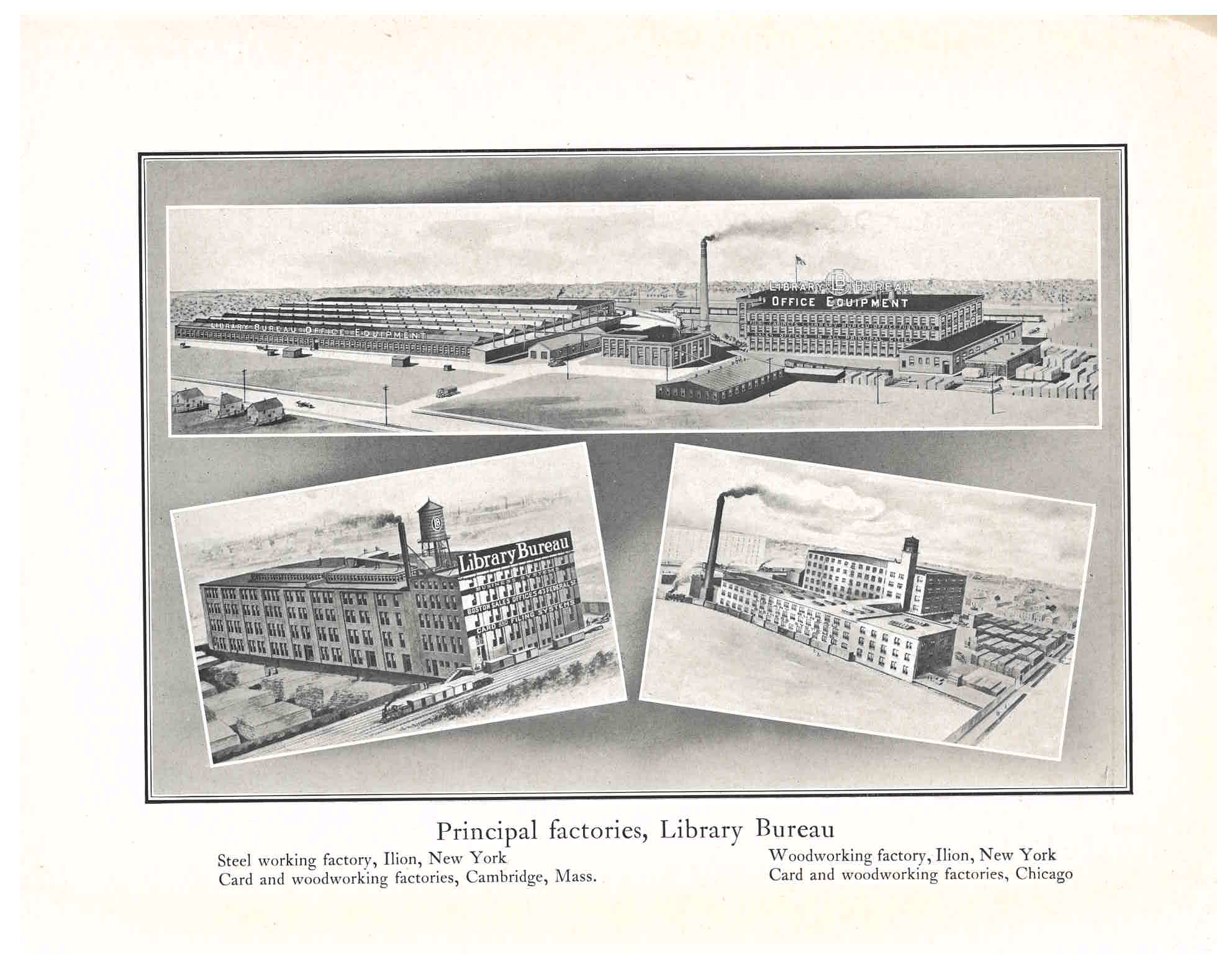

All of these supplies and many more were manufactured at the factories of Library Bureau in Ilion, NY, Cambridge, MA, and Chicago, IL. At the time this catalog was printed, those factories were devoted to steel working, woodworking, and a combination of card and woodworking. This provided a way for libraries to order standard equipment and supplies.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), unnumbered page [2], Principal factories of Library Bureau.Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918) by Library Bureau is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in more library equipment and charging systems? Take a look at a past post highlighting more library equipment and a system from 1899 that might have been used during epidemics.

Library Bureau, Cambridge, MA. Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918), unnumbered page [2], Principal factories of Library Bureau.Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018 (1918) by Library Bureau is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in more library equipment and charging systems? Take a look at a past post highlighting more library equipment and a system from 1899 that might have been used during epidemics.

Looking Forward with “Women at Work”

Last month, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives hosted Women at Work, which celebrated the lives and work of women both past and present, as well as challenged attendees to advocate for change for women in the workplace. This program, sponsored by Deloitte, featured stories of diverse women throughout history to inspire participants. This was followed by a discussion with a panel of incredible women who are leaders in their respective fields.

As the country continues to face down a global pandemic, the program recognized the continuing trend of limited access for women in the workplace. Host Gabriella Kahn pointed out that there has been a long tradition of women being allowed in the workplace in the midst of great need; however, once the crisis has passed, women are kicked out of these positions. The presentation provided several examples of this from throughout history. Many of the stories shared during the program can be found in our Women in America: Extra and Ordinary educational resources. Some are also featured in the FUTURES exhibition at the Arts and Industries building through early July.

Panelists for “Women at Work”. From left to right: Dr. Jedidah Isler, Jennifer Klein, Beth Meagher, Julie Su, moderator Ellen Stofan.

Panelists for “Women at Work”. From left to right: Dr. Jedidah Isler, Jennifer Klein, Beth Meagher, Julie Su, moderator Ellen Stofan.

During the panel discussion, Beth Meagher, the Vice Chair of the Federal Health Sector at Deloitte, commented on the importance of recognition and resilience for women in the workplace. She asked the vital question, “How do you assert yourself in a way that you are able to really capture the impact of what you’re doing and also be collaborative?”

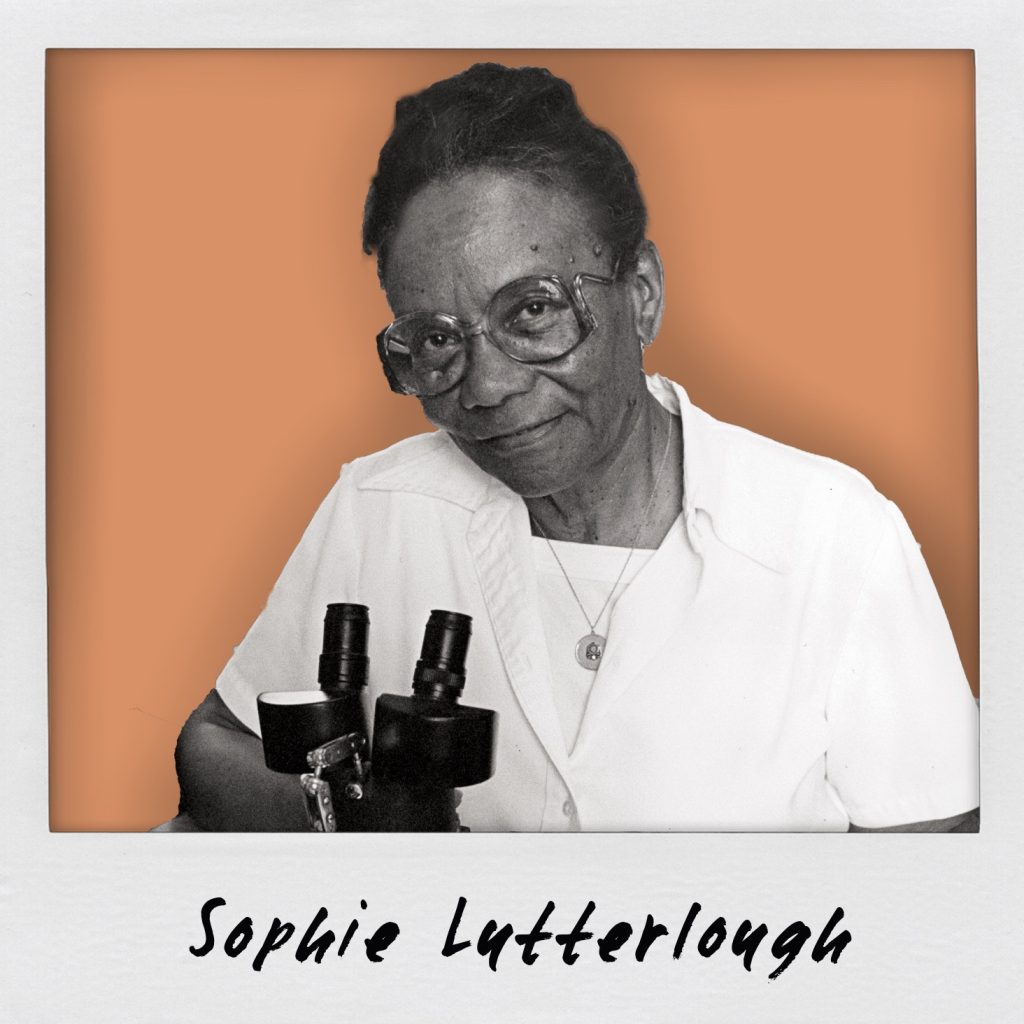

Dr. Jedidah Isler, the Assistant Director of STEM Opportunity and Engagement for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, was struck by the boundless courage of the women who paved the way, particularly with Sophie Lutterlough and her “insatiable curiosity.” Speaking of the fact that Sophie was underemployed for 14 years because of racist hiring practices in the Smithsonian at the time, she remarked, “It seemed eerily familiar to the stories of many women, particularly women of color, who are underemployed or kept from jobs which their expertise should allow them to employ. But her persistence and courage to ask for what she wanted and to start where she could are a testimony to her personal fortitude. I think it’s our job as policymakers and decision-makers to ensure that the structural barriers that led to her underemployment are faced and removed so subsequent generations don’t have to face that similar thing.”

For Jennifer Klein, Director of the White House Gender Policy Council, the only silver lining to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic has been paying attention to the plight of workers in professions that have been largely female-dominated, such as care workers: “For the first time, this country is more focused on the caregivers who have been historically women of color and have been historically undervalued, underpaid, with lower wages and fewer benefits.” The first national gender strategy that the Biden Harris administration has created examines the intersection between gender and other forms of discrimination. Joining the conversation about care workers, Julie Su, Deputy Secretary of the US Department of Labor, pointed out, “We’ve seen women leave the workforce in great numbers during the pandemic due to the lack of affordable care, and at the same time, we cannot make that about decreasing the wages and the quality of childcare workers.”

The Great Resignation, so on the forefront of the social consciousness, was another topic of discussion during the panel. Ms. Meagher astutely pointed out, “The Great Resignation is in some ways the Great Reimagination.” So much change and upheaval allow room for employees to rethink who they want to work for and what they want to do. Hybrid work is transforming the modern workplace, and Deloitte is one of many organizations trying to think through flexibility.

Ms. Klein observed that care work is at the center of the Great Resignation and that women have been overrepresented in sectors where we have seen job loss, such as retail and hospitality. Dr. Isler also weighed in on this issue, reminding the participants that resignation is not always a voluntary thing. Especially for women in science and technology, contract and temporary positions, typically filled by women of color, are often the first to go in an economic crisis. In her words, “We constantly have to be thinking about the layers and the overlapping barriers that folks are facing, and that this Great Resignation, as we call it, does not look or feel the same across the board.”

Likewise, Ms. Klein stated that if you want to address the pay gap, you have to address all areas. The gender strategy that she and her team are working to implement outlines a comprehensive government-wide approach to promoting gender equity and equality. It includes ten strategic priorities that are intentionally broad in scope, from economic security, gender-based violence, and health education to climate change, science and technology, democracy, and participation in leadership. The purpose of these priorities is to allow the Council to go deep and fully understand these issues—they are inherently linked and must be tackled in concert.

With the legacy of past women to guide and the wisdom of present women to lead, the future of the working woman is in good hands. In the words of Dr. Isler, “Girls, girls of color, LGBTQ+ women, and women with disabilities all come here with curiosity and excitement and questions about the world. It is our job to make sure they can answer those questions without undue barriers.”

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives & Wikidata: Chinese Ancestor Portrait Project

This is the third part of a series sharing Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ work with linked open data and Wikidata. For background and overview of current projects, see the first two posts in the series.

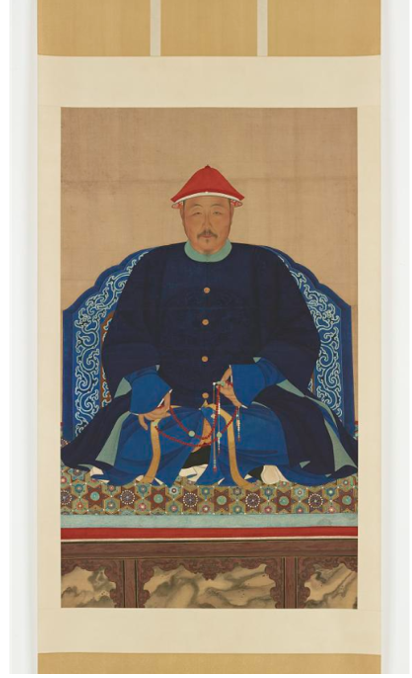

As part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives participation in the Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) Wikidata Pilot Project Wikiproject , we established the Chinese Ancestor Portrait Project (CAPP). Through this initiative, we set out to create Wikidata for 90 Chinese ancestor portraits in the collections of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the National Museum of Asian Art. You can see a list of these ancestor portraits on the PCC Wikdata Pilot Project page. One thing we wanted to do as part of our CAPP project was upload the images for these ancestor portraits.

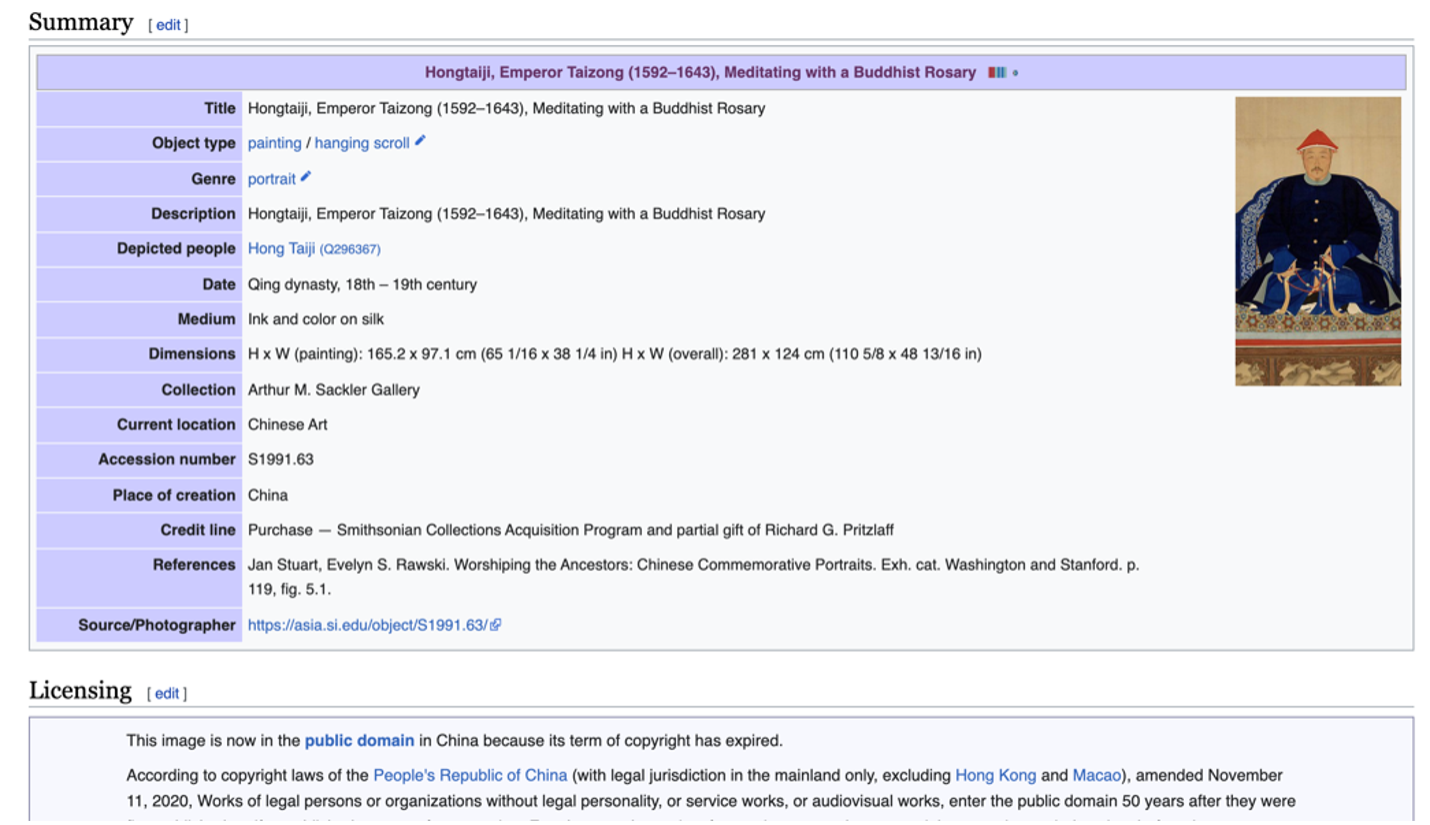

S1991.63 Hongtaiji, Emperor Taizong (1592–1643), Meditating with a Buddhist Rosary, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, National Museum of Asian Art.

S1991.63 Hongtaiji, Emperor Taizong (1592–1643), Meditating with a Buddhist Rosary, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, National Museum of Asian Art.

Initially, our primary issue was Creative Commons licensing for digital images of the paintings. Wikimedia Commons only accepts freely licensed content or content that is in the public domain. While the Smithsonian is in the process of marking materials without copyright and other restrictions with a CC0 license in support of our Open Access initiative, not all collections have been fully researched and updated. Many of the ancestor portraits have not yet been assigned a CC0 license. However, some of the images for these paintings were previously uploaded onto Google Arts and Culture, and many Wikipedians had already grabbed those images and uploaded them to Wikimedia commons. Our solution was to work with the image set that was cleared by the National Museum of Asian Art for CC0, as well as the previously uploaded images, and then describe the paintings we could not use with a set of core and extended Wikidata properties.

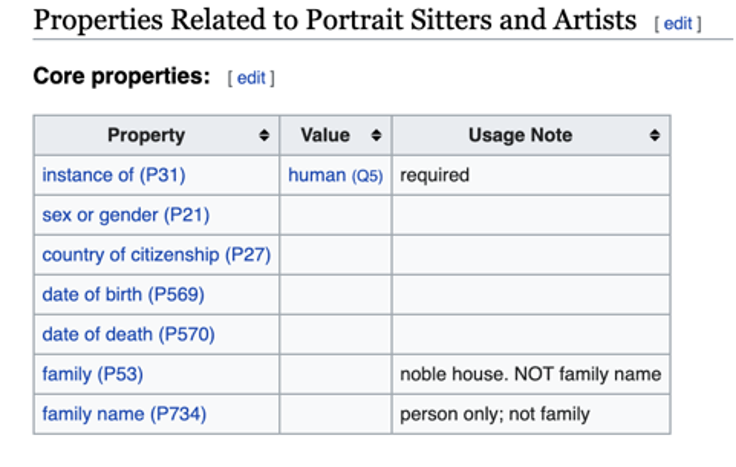

Step 1: Creating sitter Wikidata item identifiers (Q#s) and pages

We began by creating Wikidata pages for the people represented in our portraits, or sitters. Early in the process, members of the Wikidata team decided on a core-properties to be used for sitters. These core properties, known as P numbers, correspond to basic biographical data that help to describe the people represented in our paintings.

Screenshot showing core property fields of portrait sitters and artists

Screenshot showing core property fields of portrait sitters and artists

We grabbed as many extended properties as we could find through our research. This included additional biographical information about familial relationships, birth, death, location, accomplishments, rankings, etc.

Screenshot showing extended property fields of portrait sitters and artists.

Screenshot showing extended property fields of portrait sitters and artists.

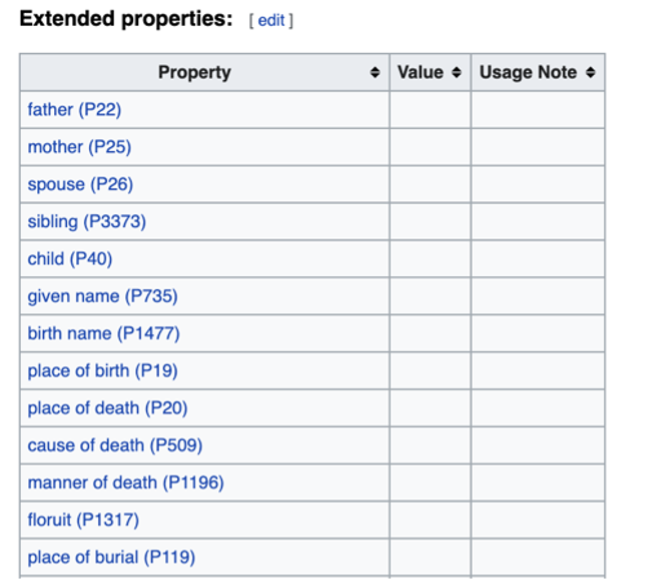

Step 2: Creating Painting Q#s/pages

The next step was to create Wikidata pages for the paintings themselves. This establishes them as separate independent entities, using an entirely different set of core and extended properties related to artwork. Information was taken from public-facing Smithsonian sites like the National Museum of Asian Art collections website and the Smithsonian Collections Search website. These properties are common descriptors for museum catalogs and curatorial notes, creating a shared vocabulary across institutions.

Screenshot showing core and extended property fields of paintings.

Screenshot showing core and extended property fields of paintings.

Step 3: Uploading to Wikimedia commons

Example 1: Previously uploaded portraits

Once the team had created Wikidata pages for each of the sitters and each of the paintings, I started by using painting titles and sitter names to comb through Wikimedia Commons. Once found, I used the Template:Artwork to augment existing data in the item summary on the commons page. The template includes much of the same information as our core properties and allows us to redirect searchers to our own catalog for better images and more information. This is particularly important because these portraits were often wrongly attributed to other collections outside of the Smithsonian.

Screenshot showing blank Template:Artwork

Screenshot showing blank Template:Artwork

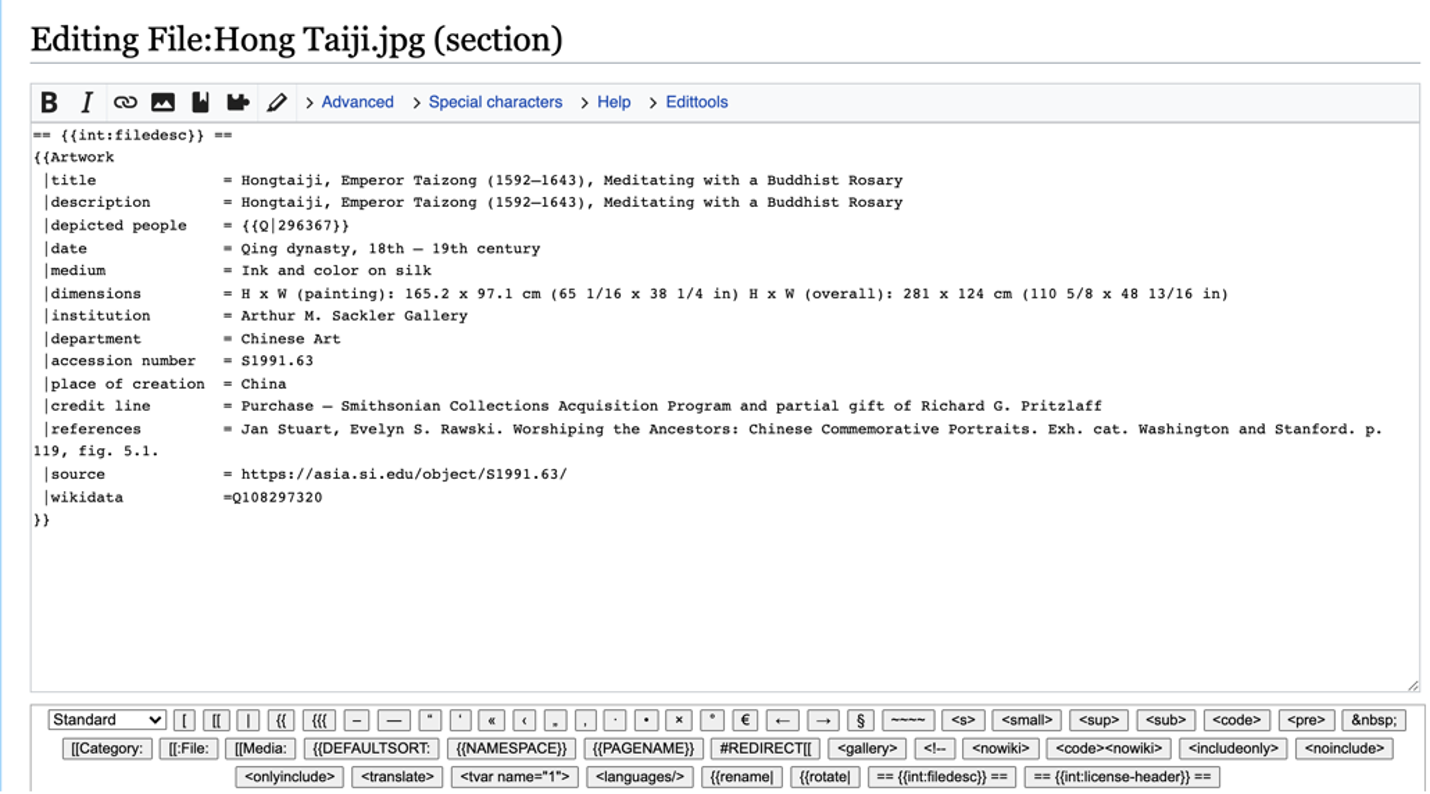

Screenshot showing template with information from Collection Search Center notation

Screenshot showing template with information from Collection Search Center notation

Notice that the inclusion of the Wikidata Q# for the sitter (Q|296367) populates a hyperlink to the Wikidata sitter page!

Example 2: Uploading new images to Wikimedia Commons

First, I needed to grab the hi-res images from the public-facing Smithsonian collections sites. Again, I only uploaded those images that already had a CC0 license. Using the Commons “Upload File” tab, I would upload them image, and then enter in the corresponding web address for the image, as well as any available artist information and the CC0 license.

The next step was to add basic description information. I kept the description short, usually including the title, time period, medium and accession number.

Screenshot showing basic descriptive date for image in Wikimedia Commons.

Screenshot showing basic descriptive date for image in Wikimedia Commons.

The following page asks for optional metadata using Wikidata P#s. Again, I referred to the core and extended properties we established for the painting Q#s. Wikimedia commons links this structured metadata back to Wikidata, pulling relevant Q# values where applicable. Users need only search for the value in the box provided.

The last step was to edit the summary info box on the resulting commons page for the image using template:artwork again. You can view the sample completed page here.

Step 4: Linking the Pages

After the Commons page is created, I linked the Commons images to both the paintings Q#s and the sitter Q#s through Wikidata. In both pages, I added the statement Image and searched for the title of the uploaded file. This can sometimes pull a lot of different images, especially since we were dealing with many important and well-known historical figures who have multiple likenesses in existence. It was best to actually save and input the exact file name. The result of adding the image to these pages is that it links the Wikidata page to the Commons page, and allows searchability through either portal. Ideally, rather than having to enter this data by hand, it would be better if future updates to these platforms could pull the structured data in from Wikidata and populate it in the Wikimedia Commons.

The end result of this project is that all of these pages “talk to each other” because of structured data and provide new discovery access points for objects in Smithsonian collections. By its very nature, new and improved access and discovery mechanisms are possible, connecting objects (works and persons) found in the Smithsonian collections and beyond. In searching through English (and sometimes Chinese) language Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons you can now find the portraits, sitters, and their descriptive metadata. More importantly, we provide the accession numbers and links to our Smithsonian-hosted collections sites to help researchers find and use our collections.

Join Us for Adopt-A-Book Events in April

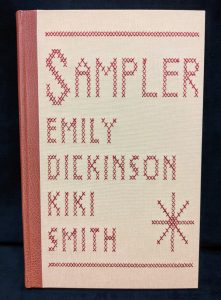

Mark your calendar for this year’s Adopt-a-Book events! Join us on April 20th and April 26th, 2022 for a closer look at our collections and the opportunity to support their preservation and acquisition.

Each year, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives (formerly Smithsonian Libraries) staff organize Adopt-a-Book events where items are “put up for adoption,” and interested supporters can adopt an item by way of a donation. The adopted item serves as an emblem of their commitment to that backing. Many who choose to adopt an item pick a book or archival document that speaks to their personal interests, like a dedicated home baker who might adopt a historical cookbook, or an avid gardener who might choose an illustrated botanical catalog.

In the past, events have been held in person, and attendees were able to see the items available to be adopted up close and to hear about the books directly from Smithsonian staff. Last year, in a virtual format, the Smithsonian Institution Archives joined the events for the first time, bringing our collections from the Smithsonian’s history to Adopt-a-Book audiences.

The Smithsonian Institution Archives is taking the lead for 2022’s virtual events! With that role, we are also expanding the types of items up for adoption. Our archival collections (and our library collections, for that matter) don’t hold just books—and not just paper-based items, either. This year we are excited to include photographic collections and audiovisual materials alongside field journals, correspondence, and botanical illustrations from the Archives, as well as a variety of books from eight library locations.

Adopt-a-Book Salons Save the Date graphic, featuring Adelia Gates botanical illustration, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7312.

Adopt-a-Book Salons Save the Date graphic, featuring Adelia Gates botanical illustration, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7312.

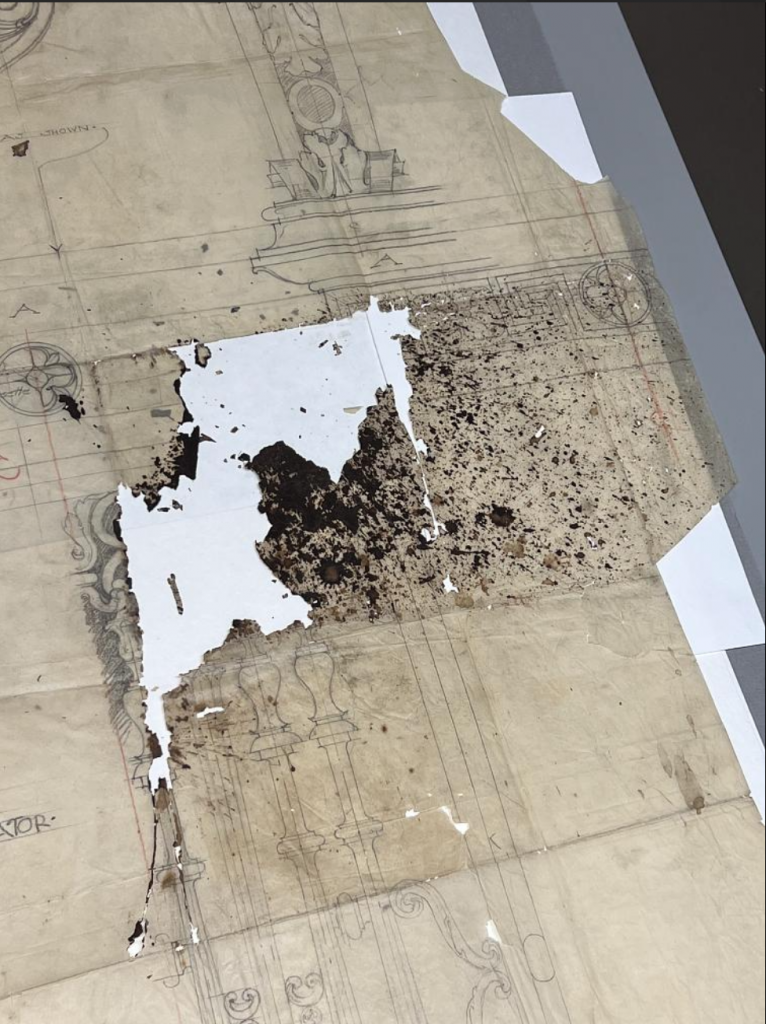

One of the items I am most excited to feature from the Archives is a drawing from the architectural records of the Smithsonian. Done on translucent paper by the architectural firm Babb, Cook & Willard, the drawing was used to sketch out design elements of an elevator in Scottish-American steel tycoon and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s turn-of-the-century New York City mansion, now the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. The elevator depicted was among the first of its kind in New York residences and is now kept in the collections of the National Museum of American History. The drawing is also interesting because of a large ink spill that obscures part of the detail, which has caused large losses and widespread embrittlement of the paper. We don’t know how the ink got spilled over the drawing, but it’s fascinating to imagine Carnegie consulting the elevator’s details at his desk and becoming distracted or startled—knocking over his inkpot in the process!

The large area of loss, or missing drawing, in this elevator diagram appears to have been caused by an ink spill. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 637. Image courtesy of William Bennett.

The large area of loss, or missing drawing, in this elevator diagram appears to have been caused by an ink spill. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 637. Image courtesy of William Bennett.

Some of the items available for adoption have been previously featured on The Bigger Picture. Check out our related resources below for links to posts describing those collections!

We are excited to host two different evening opportunities for members of the public to learn more about our collections and have an opportunity to adopt something that catches their eye. The breadth and depth of the Libraries and Archives collections will be on display, and we will celebrate the ways that they intersect and complement each other as they tell the story of the United States and of the larger world. Come join us!

Wednesday, April 20, 2022 at 5:30 PM

Tuesday, April 26, 2022 at 5:30 PM

Related Resources

- “Navigating Treatment of the Dawson Map” by William Bennett, The Bigger Picture, Smithsonian Institution Archives

- “Aww: Cute Baby Animals and Other Field Book Surprises” by Mignonette (Mig) Dooley Johnson, The Bigger Picture, Smithsonian Institution Archives

- “To Post-it or Not to Post-it” by Kirsten Tyree, The Bigger Picture, Smithsonian Institution Archives

- “The National Park that Never Was” by William Bennett, The Bigger Picture, Smithsonian Institution Archives

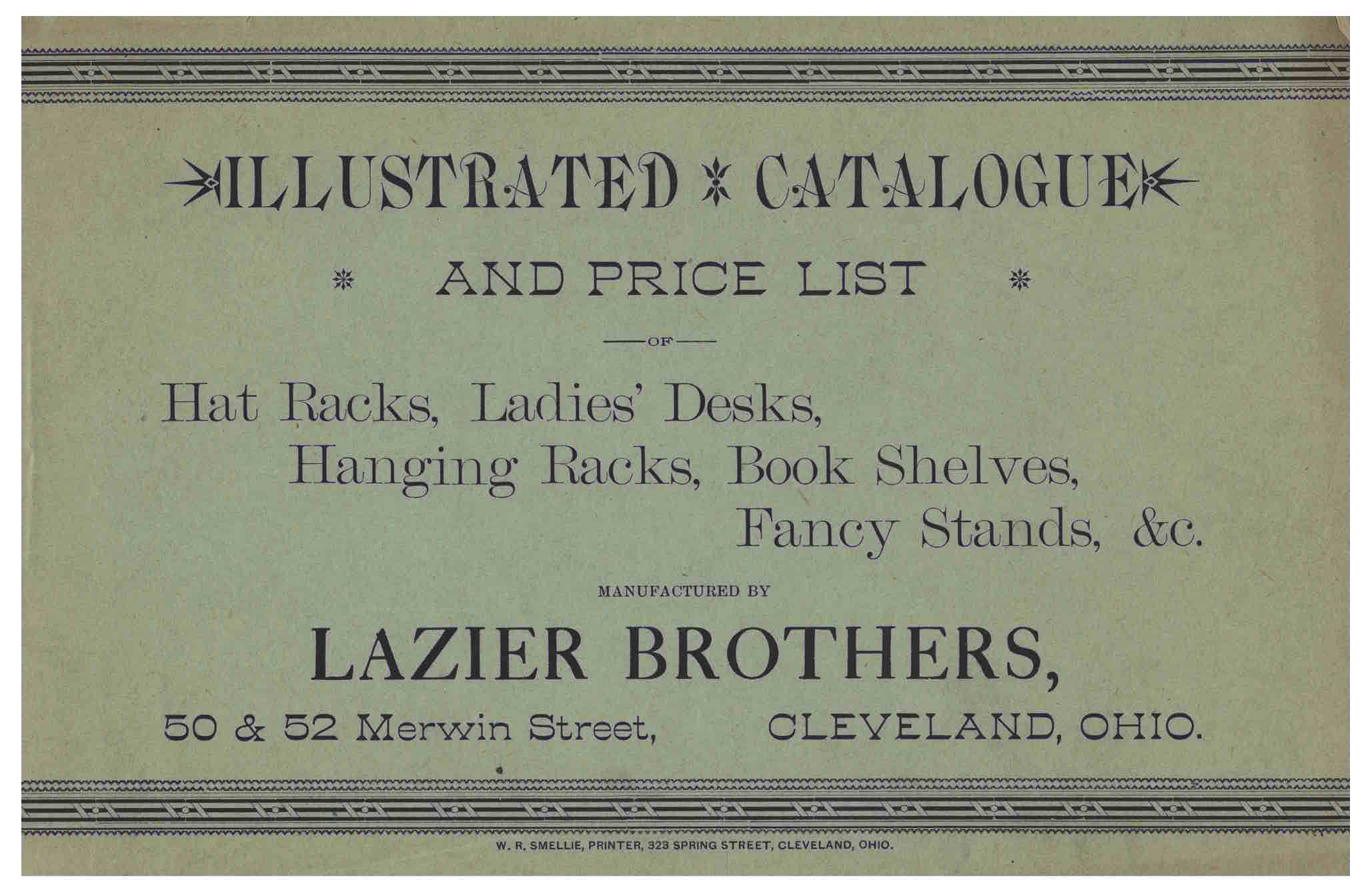

Mid-19th Century Reaction to a Laundry Invention

Today the task of laundry is simple. We load machines with clothes, add laundry detergent and softener, and check settings. But essentially, the modern washing machine and dryer do the job for us. However, in the mid-19th century, long before our modern appliances, it was not so easy. Laundry was time-consuming and labor-intensive, so perhaps this pamphlet describing a “really wonderful invention” sounded intriguing.

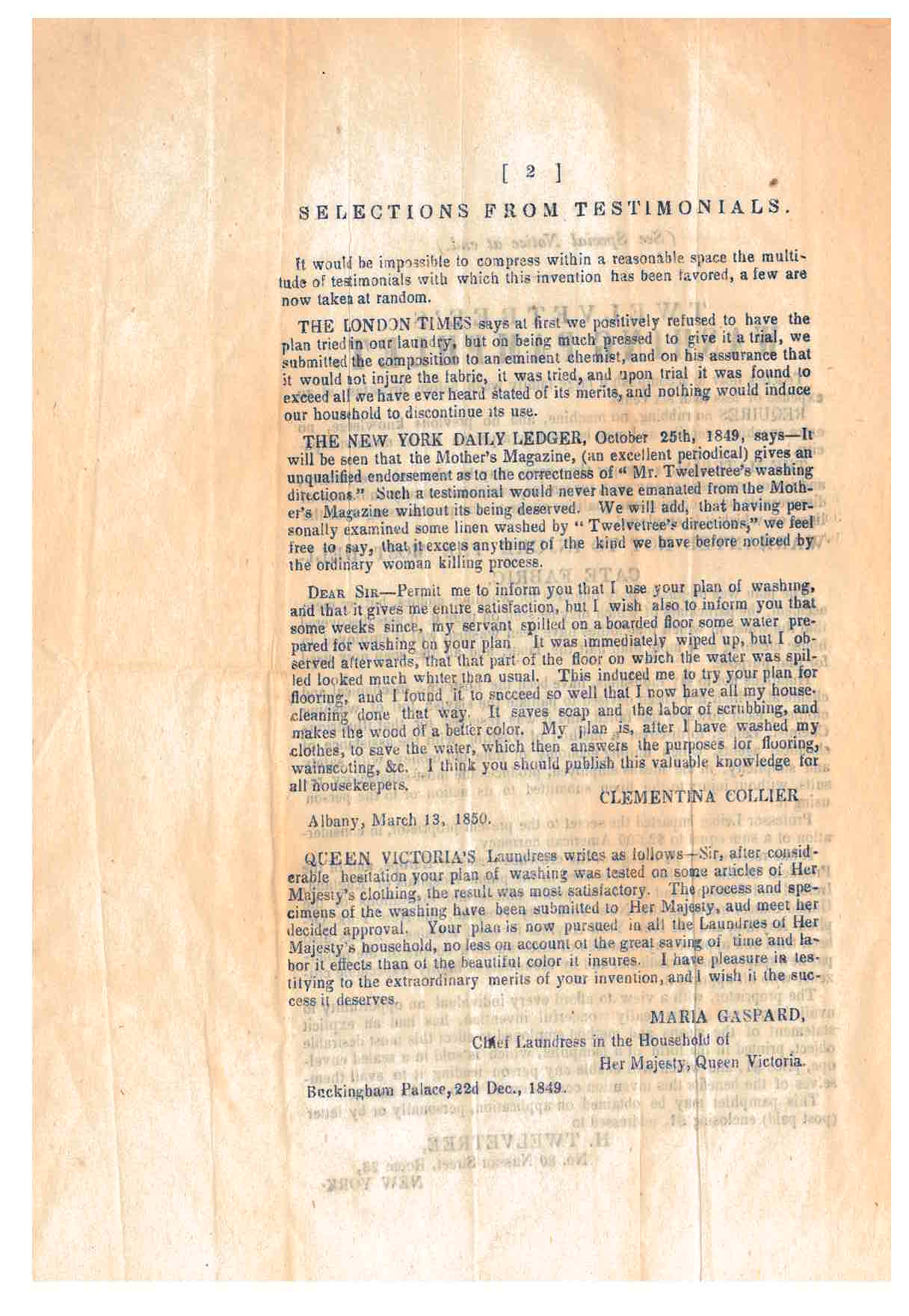

It proposed a method “to accomplish a large family wash before breakfast” without machines and without rubbing. The folded pamphlet is titled Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) by H. Twelvetree, and as we can reason from one of the testimonials found within, H. Twelvetree was most likely Harper Twelvetree (or Twelvetrees).

It does not provide step-by-step instructions, details, or illustrations to describe this new method for washing clothes. Instead, it provides only general information about the plan along with testimonials and references of those who tried it. We might call this folded pamphlet an advertising circular, as it encourages mid-19th century readers to inquire for more information and to obtain the details from H. Twelvetree.

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), front cover/unnumbered page [1], general information about washing plan.Since this particular item does not share that detailed information, we might be wondering a few things. What can this advertising circular reveal about the plan itself? How can a “large family wash” be accomplished before breakfast in the mid-19th century? And what did people at the time think of this idea?

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), front cover/unnumbered page [1], general information about washing plan.Since this particular item does not share that detailed information, we might be wondering a few things. What can this advertising circular reveal about the plan itself? How can a “large family wash” be accomplished before breakfast in the mid-19th century? And what did people at the time think of this idea?

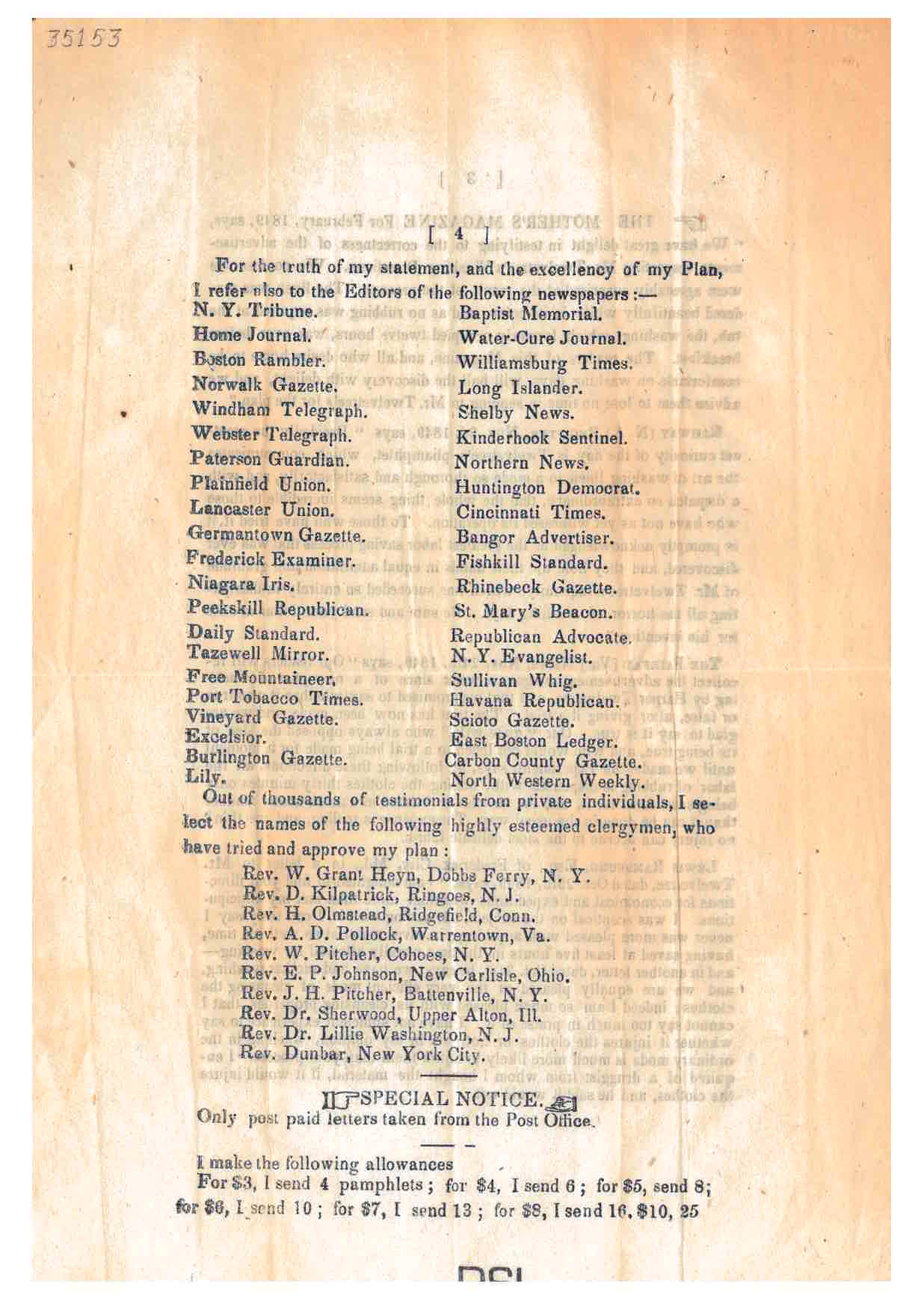

Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) explains that this method was discovered by Professor Leibig who, for a sum of money, gave permission for the proprietor, H. Twelvetree, to use it. The washing plan combined “economy of time and money, with safety and simplicity.” Ordinary individuals, high officials, and institutions were already using it. There is also a mention that the washing plan had been tested by hundreds of editors of newspapers and periodicals, including some who are listed as references in the list below.

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 4, list of references including newspaper editors and clergymen.

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 4, list of references including newspaper editors and clergymen.

The pamphlet shares a few basic components of the plan. It required no rubbing, no machines, and no extra washing utensils. Previous knowledge was not necessary. It required water, but the substance used for washing was cheaper than soap. It did not include acid, turpentine, or camphene. It did not have an unwelcome odor. And, as the pamphlet claims, it would not injure those performing the wash or destroy the fabric being washed.

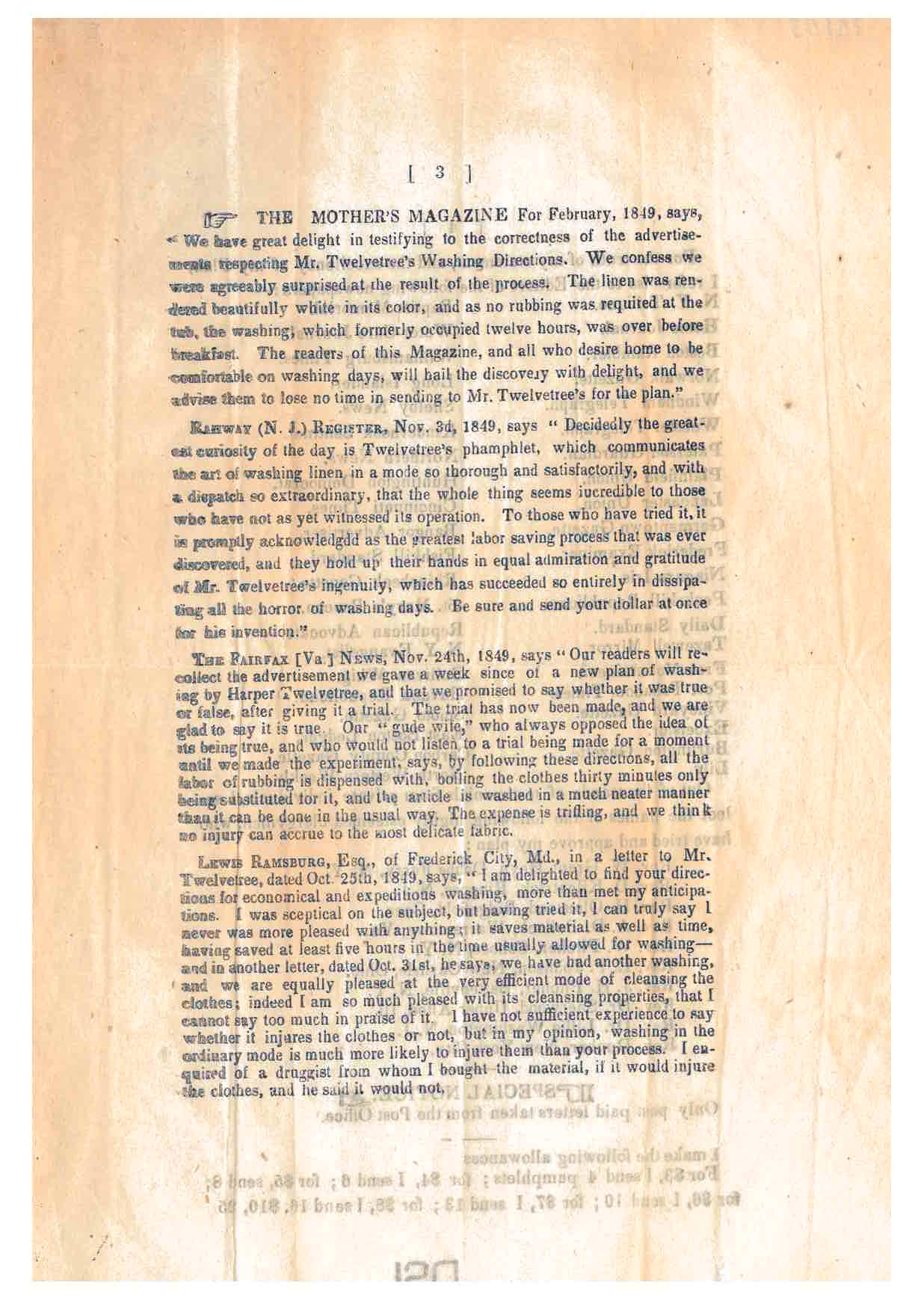

There are also two pages of testimonials which provide more information, particularly in regards to how people felt about using this new method. Similar emotions and feelings are found throughout the testimonials. Several mention their initial hesitation or skepticism but then share their surprise, delight, and satisfaction with the results. They mention advantages for their households, such as labor-saving and time-saving benefits in addition to the plan’s ability to efficiently and thoroughly wash clothes.

One of the testimonials is an excerpt from The Fairfax [Va.] News printed on November 24, 1849. It mentions an advertisement from the previous week in which they announced their trial of “a new plan of washing by Harper Twelvetree.” It continues by stating:

“The trial has now been made, and we are glad to say it is true. Our “gude wife,” who always opposed the idea of its being true, and who would not listen to a trial being made for a moment until we made the experiment, says, by following these directions, all the labor of rubbing is dispensed with, boiling the clothes thirty minutes only being substituted for it, and the article is washed in a much neater manner than it can be done in the usual way…”

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 3, testimonials of those who used “Mr. Twelvetree’s Washing Directions.”

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 3, testimonials of those who used “Mr. Twelvetree’s Washing Directions.”

The main purpose for this new idea might have been to wash clothes, but as some of the people found, there was a hidden benefit as well. On the first page, the pamphlet briefly suggests saving both soap and labor by re-using the same water for cleaning the house. Even though it does not go into great detail, we learn a bit more from a testimonial on the next page.

On March 13, 1850, Clementina Collier of Albany writes about an unexpected result of accidentally spilling water that had already been prepared with the ingredient to wash clothes. Due to this accident, Clementina Collier learned “that part of the floor on which the water was spilled looked much whiter than usual.” The testimonial continues:

“This induced me to try your plan for flooring, and I found it to succeed so well that I now have all my housecleaning done that way. It saves soap and the labor of scrubbing, and makes the wood of a better color. My plan is, after I have washed my clothes, to save the water, which then answers the purposes for flooring, wainscoting, &c…”

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 2, testimonials of those who used “Mr. Twelvetree’s Washing Directions.”

H. Twelvetree, New York, NY. Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850), page 2, testimonials of those who used “Mr. Twelvetree’s Washing Directions.”

This particular item might not describe the laundry method in great detail, but as an advertising circular, its purpose was to arouse curiosity in the hopes that people would want to learn more. It certainly inspired our curiosity and sent us on a hunt to learn more about Twelvetree’s washing tools. We found this image of a “Twelvetrees’ Villa Washer” from Cook’s Handbook for London (1881) from the University of Michigan’s collections.

Advertisement for Twelvetrees’ Villa Washer, Cook’s Handbook of London (1881). Courtesy of University of Michigan.

Advertisement for Twelvetrees’ Villa Washer, Cook’s Handbook of London (1881). Courtesy of University of Michigan.

Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) by H. Twelvetree is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in learning more about laundry in the 19th Century? A past blog post highlighting a Thomas Bradford & Co. trade catalog provides a glimpse into washing machines and related equipment in 1878.

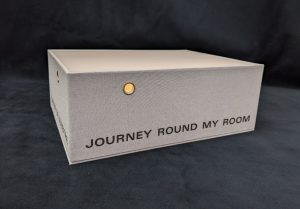

Turning a Quarantine Into a Journey With Xavier de Maistre

Porthole of “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

Porthole of “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

In a love letter to his apartment, Xavier de Maistre writes of his walls, windows, and furniture in Journey Round My Room, as if he would rather be there than anywhere else in the world. Joyful descriptions of the objects and activities in his room, such as the “quiet pleasure conveyed to his soul” during the act of dusting a painting, or the ruminations on his bed and its “agreeable colors” (rose and white) that add “not a little to the pleasure” of lying in it. As he alights his focus on particular objects, he recounts stories and memories they evoke, such as an entire chapter dedicated to just his traveling coat, “made of the warmest and softest stuff I could meet with. It envelops me entirely from head to foot, and when I am in my arm-chair, with my hands in my pockets, I am very like the statue of Vishnu one sees in the pagodas of India.”

A journey of 42 days, Chapter III, “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

A journey of 42 days, Chapter III, “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

De Maistre’s work is nearly 200 pages of such contented observations of his small space. As the world has spent more than two years enmeshed in the COVID-19 pandemic in periods of isolation in our homes, Journey Round My Room may feel like a familiar experience in 2022. However, this work was written in 1790, during the time of the French Revolution, by a soldier sentenced to house arrest for 42 days, a literal quarantine.

A young soldier, de Maistre engaged in an illegal duel, and as punishment, was placed under house arrest in Turin, seeing only the servant who brought his meals (and dressed him and made his bed—quite decadent.) It was during this confinement to just his own room that de Maistre wrote this love letter to his surroundings. Likely an attempt to thwart boredom and unhappiness at his situation, his writings were a whimsical travel diary of his close quarters, published by his brother in 1794 as Voyage Autour de ma Chambre.

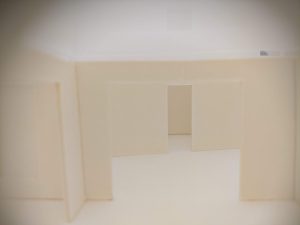

“Rooms” inside the shadowbox model of the special edition cover, “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

“Rooms” inside the shadowbox model of the special edition cover, “Journey Round My Room” by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

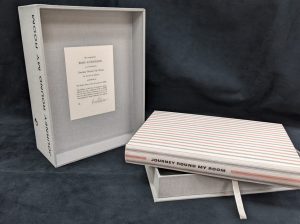

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has a beautiful copy of the 2007 Arion Press edition of Journey Round My Room, as a part of the recent gift to the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library from collector Dr. Ronnyjane Goldsmith. The book is bound in pink and white cloth, a nod to the “agreeable” rose-colored surroundings of de Maistre himself. Ross Anderson contributed more than a dozen ghostly photographs of a generic room, using a low-resolution cell phone, and printed in gray tones on translucent paper.

Of particular note for the Smithsonian’s copy is the limited special edition’s housing—a 3-dimensional apartment for the viewer to “journey” through, via portholes along the sides. Similar to a shadowbox, inside is a small white model, and each peephole allows a restricted viewing of the tiniest doors, windows, and walls of de Maistre’s imagined rooms. The cover forms the “ceiling”, made of translucent plexiglass that allows diffused light to make interesting shadows on the halls and doorways. Only 30 of the edition with this special box were created, designed by Anderson, himself an architect. The work adds to the Smithsonian’s collection of American fine press publications and is an amazing example of creativity in bookbinding.

Box and bound book, “Journey Round My Room”by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

Box and bound book, “Journey Round My Room”by Xavier de Maistre, photographs and special edition box by Ross Anderson, Arion Press, 2007

De Maistre’s reflections during a period of solitude provide a timely addition to our own, a strangely prescient reminder to take joy in simple observations, and that there are many ways to travel, not the least of which is through one’s imagination.

The Hewitt Sisters’ Diaries: Conservation and Digitization Behind-the-Scenes

This post was written by Katie Wagner, Senior Book Conservator, David Holbert, Digital Imaging Specialist, and Jacqueline E. Chapman, Head, Digital Library and Digitization. Learn more about the diaries of the Hewitt Sisters in a previous post by Jennifer Cohlman Bracchi.

In February 2020 the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives was awarded an American Women’s History Initiative grant to conserve and stabilize the 23 diaries kept by the Hewitt sisters during their travels. These diaries would eventually be featured in the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s exhibition, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum.

To support their long-term preservation, research use, and future exhibition, the diaries would be stabilized and rehoused by a contractor focused exclusively on this detailed conservation work. Afterwards, the items would be digitized by our Digitization team to provide broad access and to prevent unnecessary handling of the fragile objects.

Left: A Hewitt Sisters’ diary binder, displayed closed prior to treatment. Right: A Hewitt Sisters’ diary binder, displayed open prior to treatment

Left: A Hewitt Sisters’ diary binder, displayed closed prior to treatment. Right: A Hewitt Sisters’ diary binder, displayed open prior to treatment

What started as an exciting and straightforward project for a contractor to work on-site alongside our Preservation team, became a more challenging operation when just a month later pandemic safety protocols came into place.

To complicate matters, prior to the pandemic, six of the 23 volumes had already been sent from their usual location at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library in New York City, to our Book Conservation Lab (BCL) in Landover, MD in preparation for the exhibition. With the closure of our on-site facilities during the pandemic, retrieving and relocating the remaining volumes to the BCL was not immediately possible.

The decision was made to hire two contractors, one near the Landover location and one in New York, to conserve the diaries in their own studios, prioritizing the six diaries needed for the exhibition. The complex physical nature of these diaries demanded an innovative approach to rehousing them to maintain the integrity of the original format.

Left: An example of ephemera found in one of the diaries, prior to treatment. Right: A calling card found in a diary, prior to treatment

Left: An example of ephemera found in one of the diaries, prior to treatment. Right: A calling card found in a diary, prior to treatment

Most of the diaries were housed in commercial two-ring binders covered in leather that had degraded over time. Covers were detached, and in some cases, missing. The diaries included many scraps of ephemera from acidic newspaper clippings to calling cards, to sketches. The inclusion of these items caused some of the binders to become overfilled leading to detached pages.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives conservators worked closely with the contractors to ensure that both the pages and the ephemeral pieces maintained their original order for research purposes, preserving both the physical pages and pieces as well as the intellectual content and associations between the ephemera and the diary pages.

Each page of each diary was placed in Mylar L-sleeves and bound in a post-binding. This allowed us to retain the original order and for researchers to readily access the volumes without having to touch the fragile pages directly. The ephemeral pieces were flattened and stored separately (as many were too large for binding once unfolded) and all the elements of the original binding were housed in an acid-free double tray box.

Left: The six Hewitt Sisters’ Diaries after treatment, in new clamshell box housing, with 6 thumb drives of the photos and documentation of the conservation process. Right: An example of some of the ephemera from the diaries flattened and in mylar sleeves after treatment in a four-flap enclosure

Left: The six Hewitt Sisters’ Diaries after treatment, in new clamshell box housing, with 6 thumb drives of the photos and documentation of the conservation process. Right: An example of some of the ephemera from the diaries flattened and in mylar sleeves after treatment in a four-flap enclosure

After treatment, the diaries were ready for their time under the cameras and care of our Digitization team at our Imaging Center (IC) located in the same building as our BCL. A new challenge arose: digitization could not begin until November 29th, and the diaries needed to be back at the Cooper Hewitt by December 17th. With special permission from our Emergency Operations Group, and with numerous safety protocols in place, Digital Imaging Specialist David Holbert returned to the IC to complete this phase of the project. With extensive treatment photos and notes from the contract conservator, we were able to prepare for the imaging process in advance.

David Holbert in the process of digitizing the diaries at the Imaging Center

David Holbert in the process of digitizing the diaries at the Imaging Center

Due to their rarity and fragility, the diaries were digitized on ‘copy stand’ equipment, with a camera attached to a motorized column that can be raised and lowered. The majority of the pages were approximately the same size (6” x 4”). This allowed for an efficient workflow, with limited adjustments to the camera position. Once the correct height on the column was set for a captured image to meet resolution requirements, and in proper focus, the camera could remain at the same location for imaging each diary page.

Capturing the front and back of each page, while monitoring for focus, went quickly. But, because the pages were unnumbered, extra care needed to be taken to ensure that the original order was maintained during this work. The careful removal and re-insertion of each fragile page out of and into their protective Mylar L-sleeves proved to be the most time-consuming part of the process.

A treated diary mid-imaging, showing the new post binding and mylar sleeves.

A treated diary mid-imaging, showing the new post binding and mylar sleeves.

The oversized ephemera, pre-flattened and also housed in Mylar sleeves, were set aside and imaged separately after completing the more standardized diary pages. More camera adjustments were needed for this work, with ephemeral pieces of varying size.

The image capture process took roughly 80 hours and was completed in time for the diaries to make their return trip to New York for final exhibition preparations and installation. However, the images still required post-production work before they could be uploaded for online viewing. The images needed to be cropped, the RAW files processed into TIFFs, and page-level metadata applied to each image.

Importantly, because the original placement of these ephemeral pieces within each diary had been recorded in the conservation process, the digital surrogates of the diaries are able to reflect the original order and appearance of the diaries rather than their current housing. The digital images of each piece of ephemera were able to be inserted where the physical ephemeral pieces were originally found in each diary.

Post-production work and uploading the diaries’ digital surrogates to the Internet Archive and our Digital Library took another approximately 40 hours. All six diaries were available online by December 21st, and can be viewed in our Digital Library. In total, the diaries amounted to 1,816 images.

A thumbnail view of a selection of digitized pages from Hewitt Sisters’ Diary U.S. v.1 in our Digital Library

A thumbnail view of a selection of digitized pages from Hewitt Sisters’ Diary U.S. v.1 in our Digital Library

With these first six diaries now complete, we now turn to the remaining 17 which will go through a similar workflow for conservation and digitization. In the meantime, we are able to celebrate the opening of the Cooper Hewitt Museum’s exhibition where pages from the diaries are now safely on display.

A view of the book-viewer experience of Hewitt Sisters’ Diary U.S. v.4 in our Digital Library.

A view of the book-viewer experience of Hewitt Sisters’ Diary U.S. v.4 in our Digital Library.

Additionally, we have uploaded three of the diaries from this first batch of six to the Smithsonian Transcription Center where volunpeers (volunteer transcribers) will lend their skills and time to augmenting these images by providing searchable text, rendering them even more accessible. We look forward to sharing more diaries as the project continues, and hearing from readers, researchers, and volunpeers about their own travels through the sisters’ diaries, as we together unlock their contents and illuminate Sarah and Eleanor’s lives in their own words.

Gilded Age Girls: Exploring the Travel Diaries of Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt

Curious what might life have really been like for two wealthy, unattached New York City sisters at the turn of the 20th century? Fictional sisters Ada and Agnes from HBO’s new series, The Gilded Age, could have been inspired in part by real sisters, Sarah (1859-1930) and Eleanor (1864-1924) Hewitt. Also known as “Sallie” and “Nellie”, without them the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and its library, would not exist. A new exhibition celebrating this remarkable duo, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum, includes select pages from their never-before-seen travel diaries. Even better than seeing those few pages in person, now you can travel right alongside these two intrepid women from the comfort of your own home through six recently digitized volumes of their diaries. Plus, you can help transcribe their contents to make them even more accessible to researchers around the world!

Diaries of Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, on display in Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum.

Diaries of Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, on display in Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt: Designing a Modern Museum.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is the only Smithsonian unit founded by women. Granddaughters of industrialist and philanthropist, Peter Cooper (1791-1883), Sarah and Eleanor were pioneering women of significant means who shared their grandfather’s spirit of contributing to the greater good of American society through education. In 1895, the Hewitt sisters created the first museum of decorative arts and design in the United States—the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration. They also started a night school that worked closely with the museum’s collection, establishing an active space for design education that helped shape the American aesthetic.

Left: Photograph of Sarah Cooper Hewitt. Collection of Edward Parmee. Right: Portrait of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Bequest of Erksine Hewitt, 1938-57-737.

Left: Photograph of Sarah Cooper Hewitt. Collection of Edward Parmee. Right: Portrait of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Bequest of Erksine Hewitt, 1938-57-737.

Sarah and Eleanor’s museum became what is now Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Since becoming a part of the Smithsonian in 1968, Cooper Hewitt has told the story of its founders, yet a key component remained locked away in twenty-three diaries held in the library. Due to their extremely fragile condition, access to the diaries was restricted and their contents were unknown. To help reveal what Sarah and Eleanor documented, in 2020, Cooper Hewitt Museum and Smithsonian Libraries and Archives received a joint Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative award to support the conservation and digitization of Sarah and Eleanor’s travel diaries to make them truly accessible for the first time.

Open page from Travel diaries of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt U.S. v. 1.

Open page from Travel diaries of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt U.S. v. 1.

These small notebooks contain over four thousand pages of hand-written and typed notes mostly by Eleanor, recording their travels across Europe, the United States, and Mexico from 1913 to 1924. The Hewitt sisters kept detailed notes of their journeys to cities, towns, and villages as well as detailed descriptions and illustrations of architecture and gardens they visited along the way. Text entries are interspersed with sketches of buildings and objects, alongside inserted ephemera including newspaper clippings, note cards, hand-written correspondence, and maps. It was during these travels that the sisters amassed what became the core of the museum’s collection.

Now, with the support of Smithsonian’s Transcription Center, we invite you to not only explore these diaries, but also to help unlock their content for researchers, historians, and visitors worldwide by making them keyword searchable. As with all Transcription Center projects, we’re looking for digital volunteers to help transcribe the contents of these unique diaries to help increase their accessibility and usability.

The three diaries available in the Transcription Center are focused on the Hewitts’ travels in the U.S., including sketches and photos taken along the way:

There is no telling what these diaries might reveal and how others might use this information now that they can finally be seen!

Screenshot of digitized pages from Travel diaries of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt U.S. v. 3.

Screenshot of digitized pages from Travel diaries of Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt U.S. v. 3.

Stay tuned for our next blog post highlighting the extensive conservation treatment and digitization process of the diaries.

Further Reading:

Masinter, Margery and Matthew Kennedy, “Meet the Hewitts” blog series, CooperHewitt.org (2013-2019).

Naples, Richard. “Designing Women: The Hewitt Sisters and the Remaking of a Modern Museum“, blog.library.si.edu (October 2015).

Fannie Farmer Knew Her Pies

Cover, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Cover, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Fannie Merritt Farmer, who was born in 1857, suffered a paralytic stroke in her teenage years that stalled her dreams of a formal education. After she regained the ability to walk, she worked as a governess and developed an interest in nutrition and cooking. At the age of 30, Farmer enrolled at the Boston Cooking School, a philanthropic endeavor to help young women learn a socially acceptable trade at a time when there were limited options. Farmer did so well that she joined the staff upon graduation and became principal just two years later.

Farmer first published The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in 1896 and it would become a household staple for over a hundred years. The book includes recipes of course, but also nutritional information on common ingredients, tips about party-planning, housekeeping advice, and even health and safety information. Farmer wanted to share recipes but was also the science behind them, explaining cooking processes and including more precise measurements than many previous cookbooks. She hoped her book would “awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought and broader study of what we eat”. Farmer was an early Alton Brown!

This 1919 edition, from the collection of the National Museum of American History Library, is thought to be the last one written solely by Fannie Farmer herself. It features more than 130 illustrations of recipes, table decorations, and utensils. Our copy was previously owned by Florence E. Sparks, who added some of her own handwritten recipes on the endpages and tucked loose recipes inside. This copy was adopted through our Adopt-a-Book program by Clarice J. Peters in 2016 which supported the book’s digitization.

In honor of Pi Day (March 14th, i.e. 3/14), our staff tried two different recipes, both with tasty results. Read on for pie inspiration from Fannie Farmer and The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. Or dig into the book online to find your next dish!

Lemon Meringue Pie

Tested by Anne Evenhaugen

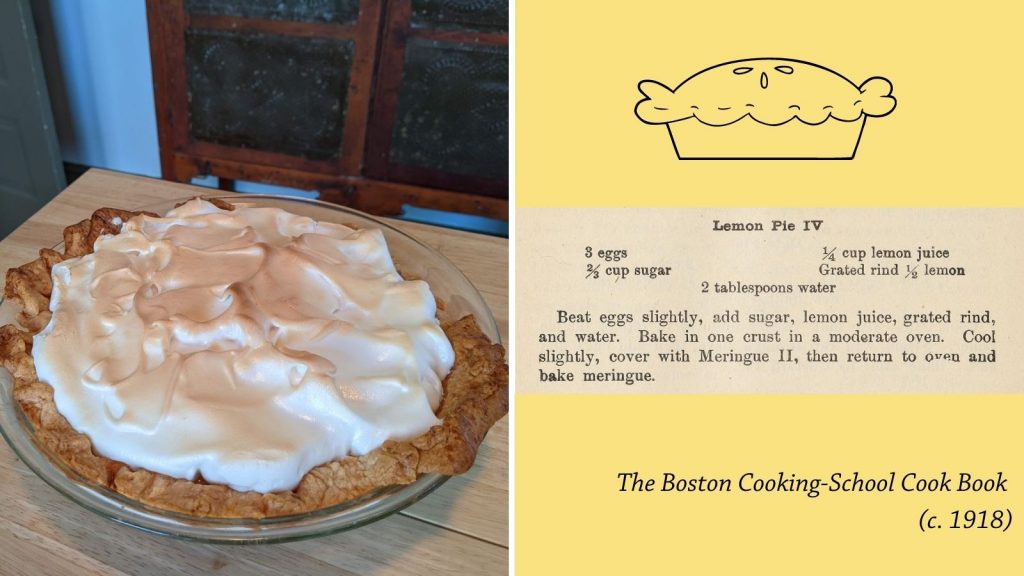

Left: Lemon Meringue Pie. Right: Lemon Pie IV recipe from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Left: Lemon Meringue Pie. Right: Lemon Pie IV recipe from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Baker’s Note: We chose to make Lemon Pie IV (page 470) with the associated Meringue II (page 480). It didn’t require many ingredients—eggs, sugar, and lemon. We cut a few corners, for example, instead of following one of Fannie’s “paste” recipes, we used store-bought crust dough. And instead of beating our eggs for our meringue with a “silver fork,” we used our stand mixer! But otherwise, we followed the recipe nearly to the letter, with a moderate oven (that is 375 F for the modern reader!). The verdict of our family was that Farmer’s recipe was delicious. Even the person who normally doesn’t like lemon meringue said it was great–not too sweet! I would make this again since it was so easy, and both kids helped.

Lemon Pie IV

Ingredients:

- 3 eggs

- 2/3 cup sugar

- ¼ cup lemon juice

- Grated rind of ½ lemon

Directions:

- Beat eggs slightly, add sugar, lemon juice, grated rind, and water.

- Bake in one crust in moderate (375 F.) oven

- Cool slightly, cover with Meringue II (see below).

- Return to oven to bake meringue (about 8 minutes)

Meringue II

Ingredients:

- Whites from 3 eggs

- ½ teaspoon lemon extract or 1/3 teaspoon vanilla

- 7 ½ tablespoons powdered sugar

Directions:

- Beat whites until stiff.

- Add four tablespoons of sugar gradually and beat vigorously.

- Fold in remaining sugar and add flavoring

Blueberry Pie

Tested by Erin Rushing

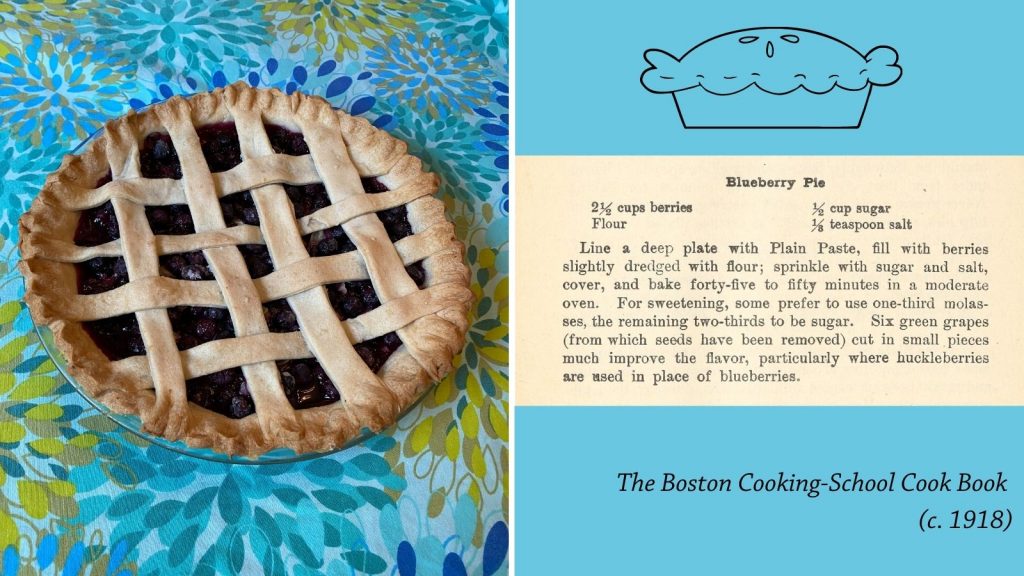

Left: Blueberry Pie. Right: Blueberry Pie recipe from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Left: Blueberry Pie. Right: Blueberry Pie recipe from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (c.1918).

Baker’s Note: The hardest part of this recipe was managing the crust. Farmer recommends using “Plain Paste” (page 463), which was a bit tricker than the name implies. Unable to find lard at the grocery store, I substituted shortening. I opted not to wash my butter despite Farmer’s recommendation and just used unsalted. Finally, the lamination process of folding and rolling the butter to incorporate it was a floury disaster for me. I ended up chucking all of the ingredients into a food processor and the end result was just fine. Also worth noting: Farmer suggests a “deep plate” for the filling, but this filled a standard pie plate (not deep dish) perfectly. The grapes were an unusual addition but no tasters could tell they were there!

Plain Paste (Pie Dough)

Ingredients:

- 1 ½ cups flour

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 1/4 cup lard (or shortening)

- ¼ cup cold butter, cut into small pieces

- Cold water (about 4-6 tablespoons)

Directions:

- Mix salt with flour.

- Cut in lard/shortening, either with pastry cutter, fingers, or using food processor.

- Add water, a tablespoon at a time, until ingredients form dough.

- Cut in butter using preferred method until evenly distributed.

- Turn out onto floured surface. Divide into half. Form two balls and then roll out to size, using one ball to create lattice pieces if desired.

Blueberry Pie:

Ingredients:

- 2 ½ cups berries

- 6 green grapes, cut into small pieces (optional)

- Flour (about 1 tablespoon)

- ½ cup sugar

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

Directions:

- Line a pie plate with Plain Paste (or your preferred pie crust).

- Slightly dredge berries and grapes with flour. Pour into crust.

- Cover with top crust or decorate with strips.

- Bake 45-50 minutes in a moderate oven (375 F.)

- Allow to cool completely, several hours or overnight, before cutting.

Further Reading:

Eschner, Kat. “Fannie Farmer Was the Original Rachael Ray”, Smithsonian.com (August 23, 2017).

Farmer, Fannie Merritt. The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1919).

“Farmer, Fannie Merritt, 1857-1915”, Feeding America: the Historic American Cookbook Project. Michigan State University Libraries.

The Bamboo Expert Who Rediscovered a Missing Grass

Argentine grass expert Dr. Cleofé E. Calderón (1929-2007) collected species, published descriptions of rare and unusual plants, and led workshops that helped shape the field of bamboo taxonomy. Affiliated with the Smithsonian for much of her agrostology career, Dr. Calderón’s legacy can be traced in collections across the Institution, including publications, field books, and photos in Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

Visiting Argentine botanist Cleofé E. Calderón with plant specimens and microscope. Detail of digital contact sheet. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-008 [OPA-90]Dr. Calderón was a botanist from the University of Buenos Aires who came to the Smithsonian Institution to study bamboo. In the 1960s she visited Washington, D.C. and stopped by the U.S. National Herbarium in the Department of Botany at the National Museum of Natural History. The connections she made during that visit led to a close working relationship with Curator of Grasses, Dr. Thomas R. Soderstrom.

Visiting Argentine botanist Cleofé E. Calderón with plant specimens and microscope. Detail of digital contact sheet. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 11-008 [OPA-90]Dr. Calderón was a botanist from the University of Buenos Aires who came to the Smithsonian Institution to study bamboo. In the 1960s she visited Washington, D.C. and stopped by the U.S. National Herbarium in the Department of Botany at the National Museum of Natural History. The connections she made during that visit led to a close working relationship with Curator of Grasses, Dr. Thomas R. Soderstrom.

Dr. Tom Soderstrom and Dr. Cleofé Calderón, 1975, by Kjell Sandved, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 95-013, Image No. SIA2013-04116.

Dr. Tom Soderstrom and Dr. Cleofé Calderón, 1975, by Kjell Sandved, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 95-013, Image No. SIA2013-04116.

With support from several Smithsonian offices and the National Geographic Society, Dr. Calderón traveled worldwide to research and collect specimens. Her work had a special focus on Central and South America, particularly Brazil. In 1976, she and colleagues spent ten weeks studying and collecting bamboo in the Mata Atlântica forest of eastern Brazil, an area known for its plant diversity. It was during this trip that Dr. Calderón made one of her most important botanical discoveries–observing and collecting Anomochloa, a genus of grass that scientists had not seen living since the 19th century.

Specimen of Anomochloa marantoidea Brongn collected by Cleofé E. Calderon in Brazil in 1976. National Museum of Natural History.

Specimen of Anomochloa marantoidea Brongn collected by Cleofé E. Calderon in Brazil in 1976. National Museum of Natural History.

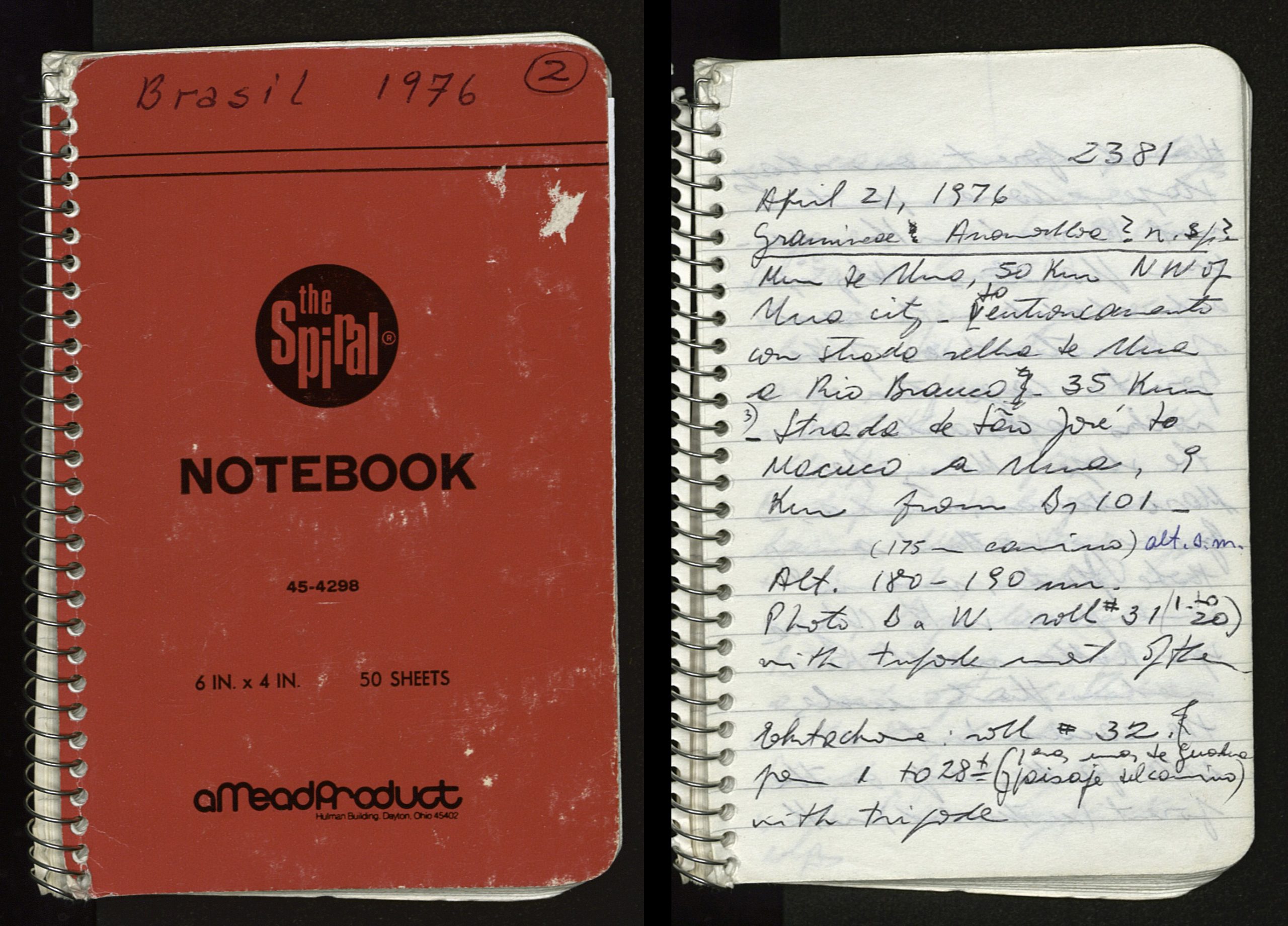

Dr. Calderón’s field books in our Smithsonian Institution Archives help us understand what she saw during her travels. These 17 field books created between 1967 and 1981 provide context for the many specimens she observed and collected. Her detailed notes were part of her thorough documentation process, which also included capturing photographs with two cameras. Dr. Calderón recorded taxonomic names of specimens, temperatures, altitude/elevation, flowering, and inflorescence. In 2019, Smithsonian Transcription Center volunteers helped transcribe Dr. Calderón’s field books to make them even more useful to modern researchers.

During her work with the National Museum of Natural History, Dr. Calderón contributed about 1,000 plant specimens to the U.S. National Herbarium and was known for her thoroughness and high-quality pressings. Many have been digitized and are available through the Smithsonian’s Collection Search Center. According to her obituary in Bamboo Science and Culture, her specimens “are of great significance to grass systematics due to both their quality and the large number of novelties represented among them.”

Field book of Cleofé E. Calderon. “Brasil 1976, 2”. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 12-005.

Field book of Cleofé E. Calderon. “Brasil 1976, 2”. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 12-005.

Left: cover; right: April 21, 1976 entry.

Dr. Calderón also shared her research by co-authoring a number of publications, including two titles in the Smithsonian Contributions to Botany series, available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Both “Morphological and Anatomical Considerations of the Grass Subfamily Bambusoideae Based on the New Genus Maclurolyra” (1973) and “The Genera of Bambusoideae (Poaceae) of the American Continent: Keys and Comments” (1980) were written with long-time collaborator Thomas Soderstrom.

Cover, “The Genera of Bambusoideae (Poaceae) of the American Continent: Keys and Comments” (1980).

Cover, “The Genera of Bambusoideae (Poaceae) of the American Continent: Keys and Comments” (1980).

Dr. Cleofé Calderón left the field of botany in 1985 and began working for a bibliographic service. By then, she had named 18 grass and bamboo species. In addition, one genus of ornamental grass, Calderonella, was named in her honor by Soderstrom and Henry F. Decker. Her specimens, field books, and publications continue to lend valuable insight to modern researchers.

Further Reading:

Calderón, Cleofé E. Cleofé E. Calderón Field Books, 1967-1981 and undated. Smithsonian Institution Archives SIA Acc. 12-005.

Calderón, Cleofé E. and Thomas R. Soderstrom. “The Genera of Bambusoideae (Poaceae) of the American Continent: Keys and Comments” , Smithsonian Contributions to Botany, No. 44 (1980).

Calderón, Cleofé E. and Thomas R. Soderstrom. “Morphological and Anatomical Considerations of the Grass Subfamily Bambusoideae Based on the New Genus Maclurolyra” Smithsonian Contributions to Botany, No. 11 (1973).

“Cleofé E. Calderón (1929-2007)”, Bamboo Science and Culture: The Journal of the American Bamboo Society 21(1): 1-8 (2008).

Soderstrom, Thomas R. and Henry F. Decker “Calderonella, a New Genus of Grasses, and Its Relationships to the Centostecoid Genera”, Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, v. 60 (1973).

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives & Wikidata: Plans Become Projects

This post is part of our Smithsonian Libraries and Archives & Wikidata series.

Over the past two years, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has embarked on a linked data journey along with many other libraries in the Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) Wikidata pilot project. From October 2020 to August 2021, the Libraries Wikidata team experimented with creating and maintaining name authority in a completely new way, including plans to install a decentralized Wikidata instance (Wikibase) that would meet the Smithsonian policies and best practices. This is the second part in the Wikidata blog post series, be sure to read our previous post for additional information.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Wiki initiation commenced with a Wikidata workshop held in November 2019 with Andrew Lih, currently the Wikimedian-In-Residence for the American Women’s History Initiative. The outgrowth of the workshop was a name reconciling project using carefully curated name data. During the pandemic, this process was expanded to include additional staff and two name datasets: 1) the Art and Artist Files database and 2) a portion of Smithsonian American Art Museum’s artist names from its database.

For the last two years, the Libraries’ Wiki project has mainly focused on Wikidata and Wikibase, and briefly experimented with Wikimedia Commons for images as part of the Smithsonian’s PCC Wikidata Pilot Projects (Oct 2020- Sep 2021).

Wikidata, launched in 2012, is a global and open knowledge repository of structured data that serves as a hub for linking resources. This linked open data information cloud attracts and integrates authority data from many libraries. Wikidata quickly became the authority knowledgebase of choice in libraries and commercial institutions for names for people, places, etc. Its structured data gives many developers a way to create tools to query and present findings on trending topics, such as the resources which impact or are impacted by the pandemic, COVID-19 (http://coviwd.org)

Wikidata has become a high-demand library authority identifier clearing house. The PCC Policy Committee recognized the platform could play a role in its effort to transform authority control into identity management. In September 2020, called for a pilot among the PCC member libraries. The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives assembled a team to participate in October 2020 as telework projects during the pandemic.

The Wikidata team prioritized the following goals in order to create cohesive processes for names (identity) management for the Smithsonian’s collections,

- The creation and curation of names for CPF (corporate bodies, persons and families), collections, and publications for the Institution.

- Adopting replicable workflows to SI units that would work beyond the Libraries and Archives’ cataloging or metadata professionals.

- Increasing professional curiosity toward descriptive data and what it could offer to users as a service.

- Transitioning to a localized deployment of a Wikidata model (in Wikibase) that meets Smithsonian policy and best practices guidelines.

- Encouraging ingenious API tools development to feature Smithsonian collections.

- Forming collaborative efforts with colleagues within and beyond the SI walls.

The five projects from the Libraries and Archives’ Wikidata team for the PCC Wikidata Pilot Project are as follows:

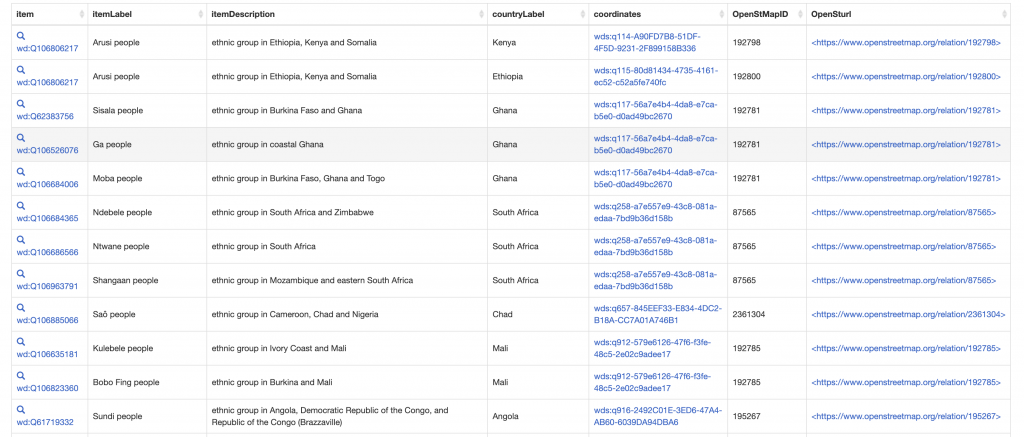

1) African ethnic groups

Reconcile, edit and/or add African ethnic group names (ca. 250) currently used in local subject headings by the Warren M. Robbins Library of the National Museum of African Art.

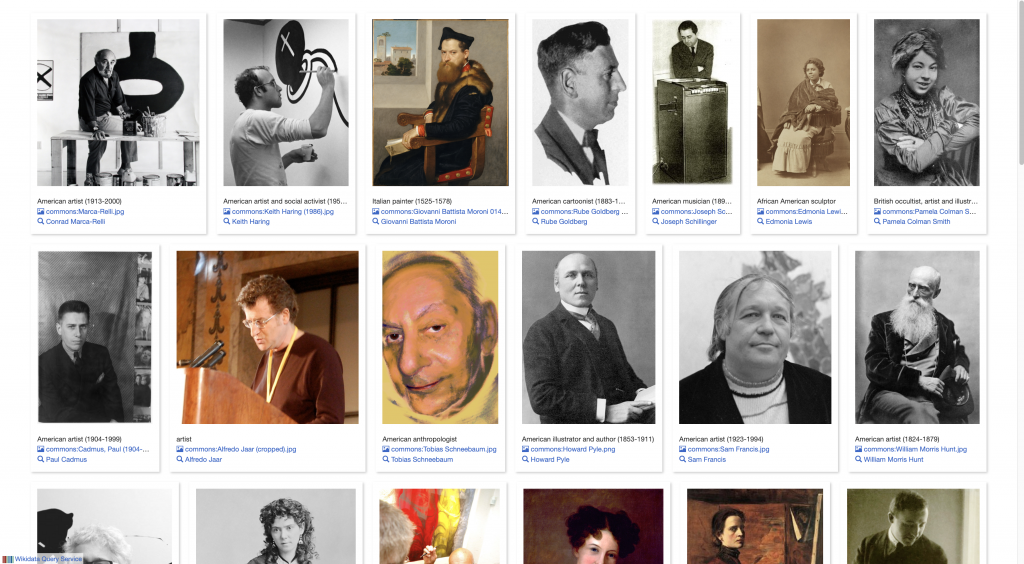

2) Artist files

Reconcile, edit and/or add the artists descriptive data matched in two SI artists databases (the Libraries and Archives’ Art and Artists Files and Smithsonian American Art Museum’s artists databases), which amounted to 3797 artists.

3) Chinese ancestors portraits (primarily royal family members of the Qing Dynasty of Manchu ethnic group)

Review and augment for accuracy Wikidata statements for 90 names matched to the Freer and Sackler Galleries collection of Chinese Ancestors portraits.

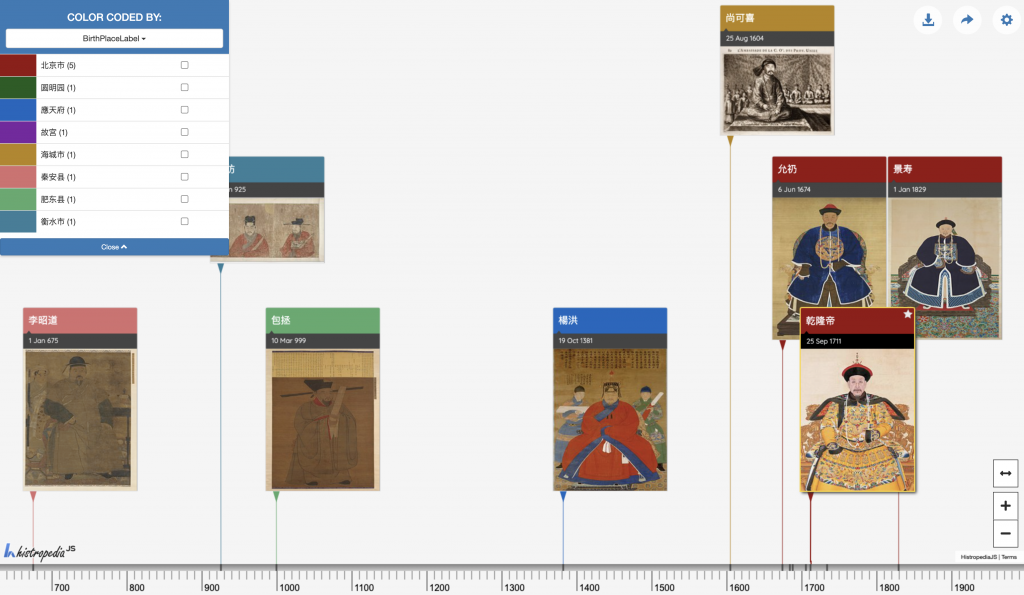

Chinese ancestors portraits organized by date of birth in Chinese scripts, on Histropedia site: http://tinyurl.com/CAPPtimeline.

Chinese ancestors portraits organized by date of birth in Chinese scripts, on Histropedia site: http://tinyurl.com/CAPPtimeline.

4) Dibner scientists portraits

Reconcile, edit and/or add the scientists and artists featured in the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology’s collection of portraits included on the Scientific Identity website.

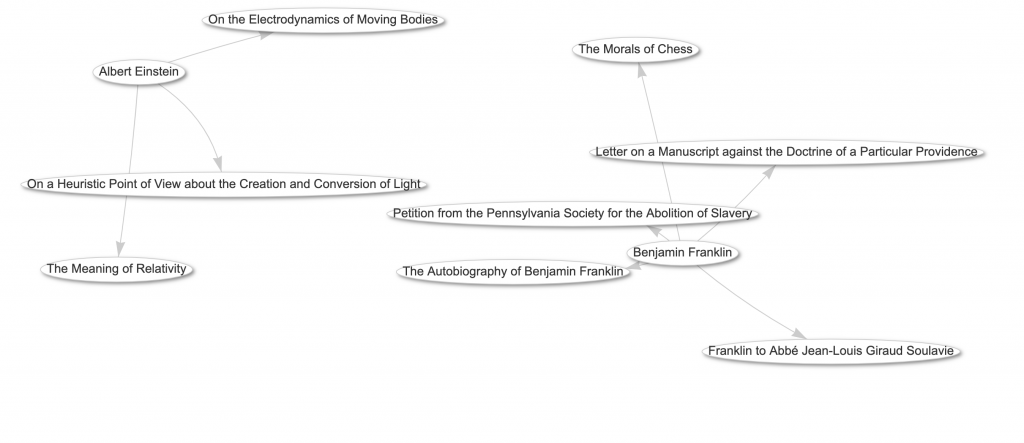

Graph showing scientists’ publications available in Wikisource, an open wiki library for digitized texts.

Graph showing scientists’ publications available in Wikisource, an open wiki library for digitized texts.

5) Smithsonian researchers and their publications from the Smithsonian Research Online (SRO)

Reconcile, enhance and/or add names for the notable curatorial and research staff from the Smithsonian Profiles website and review the representation of Smithsonian in Wikidata.

People related to the Smithsonian through employment, affiliation, and membership, (past and present) with images.

People related to the Smithsonian through employment, affiliation, and membership, (past and present) with images.

Each project identified the specific aspects, focus, and workflows documented on the Smithsonian PCC Wikidata Pilot Page. The project team met weekly; subgroups met bi-weekly on a regular basis or as needed. A team conducted a few samplers to showcase contributions to the overall Smithsonian collections in the Wikidata landscape. These queries were gathered and put together as a dashboard highlighting various characteristics of each individual project in table forms, maps, and graphs.

Wikibase, an extension of MediaWiki, is the software that powers Wikidata. It offers a suite of open source software for creating a collaborative knowledge base. It also allows for localized configuration and an option to federate with other Wikibase installations and Wikidata at-large.

Several institutions have established substantive workflows for deploying a decentralized Wikidata utilizing Wikibase software. Examples include Rhizome’s Artbase, the Digital archive of artists’ publishing (DAAP), the Enslaved.org, Linked Jazz, DNB’s GND, FactGrid, Luxembourg’s Shared Authority File, and Europeana Eagle, etc.

Members of the Libraries and Archives’ team were exposed to the richness and potential of structured data describing the collections that they are passionate about. In addition, participating staff gained new technological skills and new approaches to information organization in a linked and open repository like Wikidata. And they are excited about the potential for deployment of a local Wikibase instance that enables us to better address Smithsonian internal policies and formulate best practices and guidelines for our workflow.

At the writing of this post, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has been piloting a Wikibase instance, investigating limited functionalities. To date, the team has created over 200 properties and close to 1590 items, currently only accessible to Smithsonian staff.

The substantial work of the Libraries and Archives’ Wikidata team has been recognized by colleagues around the world. Our team members are part of a larger community helping to shape developments and features of Wikidata and Wikibase. For instance, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives was one of the first organizations that the WikiLibrary Manifesto, spearheaded by the German National Library, invited to sign the initiative. Throughout Fiscal Year 2021, the Wikidata team conducted several presentations illustrating the potential of Wikidata as a viable tool for our collections.

In an effort to further unveil our collections through digital solutions, the Wikidata team is devising future plans to continue wikifying entities for the collections in a localized Wikibase to accommodate Smithsonian policy and best practices, without sacrificing discovery and reuse of Smithsonian data!

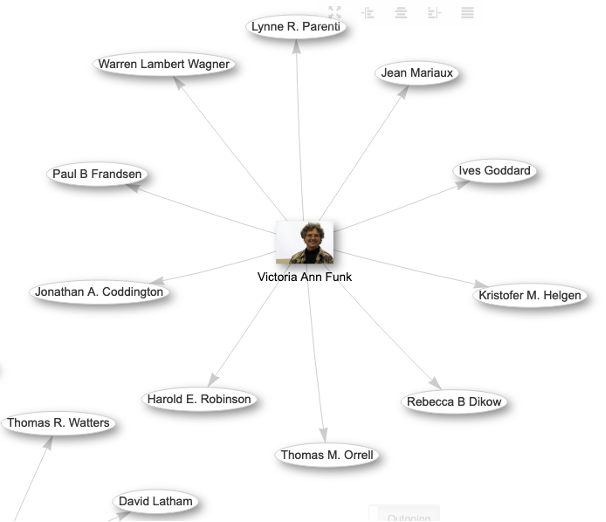

National Museum of Natural History researcher Victoria Funk (1947-2019) co-authorship network, https://w.wiki/4LQv

National Museum of Natural History researcher Victoria Funk (1947-2019) co-authorship network, https://w.wiki/4LQv

Further Reading:

- Barbara Fischer. Authority Control meets Wikibase (2019): https://wiki.dnb.de/display/GND/Authority+Control+meets+Wikibase.

- French National Entities file (FNE): project overview (2019): https://www.transition-bibliographique.fr/fne/french-national-entities-file/

- Wikibase site showcases variety of implementations: https://wikiba.se/showcase/

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Wikidata Team presentations: