Libraries' Blog

Go West! Then Back to the Future.

History is full of narratives and those narratives have a history. As a high school history teacher, I went into my Neville-Pribram Mid-Career Educator fellowship with a motivation to help my students better understand where popular history narratives come from so they can better predict where they are going. Look to the past to predict the future? Easy peasy, right?

Michael Skomba, 2019 Neville-Pribram Mid-Career Educator Award Recipient.

Michael Skomba, 2019 Neville-Pribram Mid-Career Educator Award Recipient.

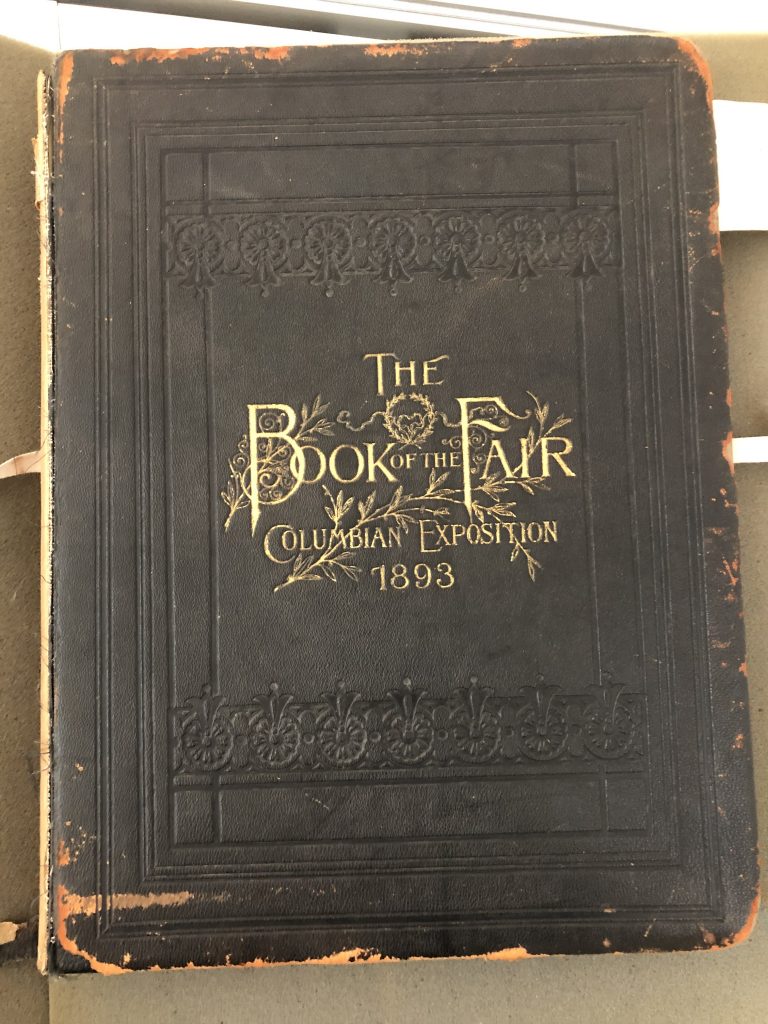

As a mostly world history and big history teacher studying at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library, I naturally flocked to the 1893 The Book of the Fair by Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Book was a popular recounting and survey of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, a non-critical celebration of American achievement. During my fellowship, I corresponded with a Bancroft authority, Dr. Travis Ross of Yale University, who I believe said it the best and I kept going back to his analogy with my students; the Book was analogous to a popular Netflix show as they were both “algorithmically perfected to maximize the market for an expensive work.”

I have been trained to teach in the discipline of Big History. French Historian Fernand Braudel believed that the most useful historical questions and analysis come from studying the “deep currents” of history; this translates to the study of ordinary people rather than just icons and focusing on transdisciplinary thinking as opposed to solely highlighting political and military history. A source such as The Book of the Fair allowed for a popular history that flipped geographic scales and meshed with a big history mindset. A big history pedagogical approach focuses on a cohesive cosmological, geological, and human narrative that goes so deep below the waves that they make Jacques Cousteau look like a vacationer snorkeling with his kids.

Cover of The Book of the Fair (1893).

Cover of The Book of the Fair (1893).

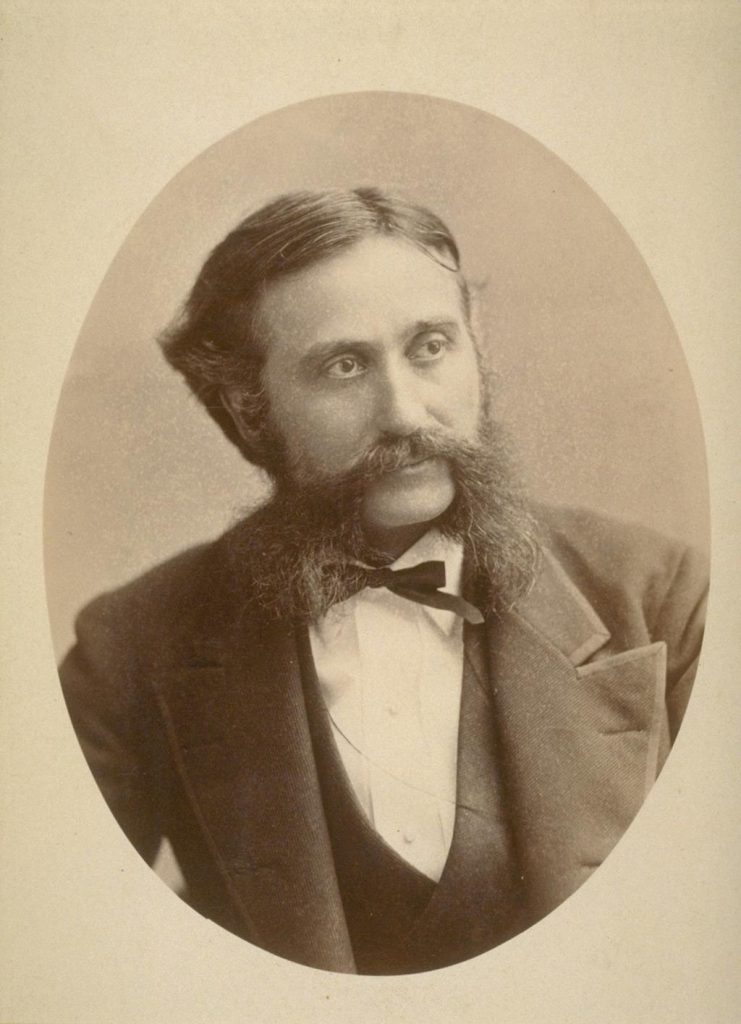

The 2019 fellowship at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library forced a timely self-interrogation for the impending ‘real history’ conversations. As anyone who has picked up a newspaper or turned on a TV in the past couple of years can tell you, the culture wars have come to history class. As a teacher, I have spent barbeques and holiday parties being asked by those on both sides of the aisle if I am teaching the ‘real history.’ I have been prepared for these fleeting moments on the axis of good conversation and self-actualization by staying out of the “waves.” It revealed that despite my global lens, I needed to zoom in and refocus. My American history lens was more of an implicit kaleidoscope– I had been stuck in the waves of American “Mythistory.” I had not yet gotten the memo about the revisionist thinking about the history of the American West. I had lived and taught in the Eastern Navajo Nation. I had spent time telling the Diné Code Talker’s story. Regardless, some of the old American West tropes remained hidden in my psyche, lodged somewhere between Clint Eastwood and ideas of pristine western wildernesses. Ironically, it took a figuratively global text written about the literal World’s Fair of 1893 to make this problem crystalize. For this academic adventure, we go below the waves to examine one man who told the story of the genesis of the American West. After I was encouraged to investigate the source of the Book, Hubert Howe Bancroft revealed our worthy problem. Bancroft achieved the unthinkable at the time by writing an affordable and all-encompassing history of the American West titled The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, but the dilemma lies in his integrated perspectives on race, gender, and class.

Anyone who has spent time with young people could probably tell you that the idea of a mid-nineteenth century mutton-chopped historian is not breaking into the TikTok top views. So how do I code this problem to appeal and engage young learners? Short Answer: “What is the California Dream?”

The Typical Classroom Conversations Around This Lesson:

“What does Bancroft have to do with the California Dream, Mr. Skomba?”

“Bancroft is known as the first to write a comprehensive history of California and the American West. He moved to San Francisco shortly after the Gold Rush and made his fortune in selling, writing, and publishing books. He lived his California Dream and established the mythistory of California for others seeking fortune and new opportunities. From the Gold Rush to YouTube influencers today, he incubated the mythistory of California…”

Photo of Hubert Howe Bancroft, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Photo of Hubert Howe Bancroft, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

My original intent was to use The Book of the Fair to place America in the late Industrial Revolution, a natural connection to our study of the Anthropocene. I even called on additional rare natural history texts to complement. As I scanned the delicate pages with the expert advice of Cooper-Hewitt Head Librarian and research miracle-maker Jennifer Cohlman Bracchi, we found the Book to be a zeitgeist piece, a monolithic feel-good source about the American Coming of Age (The feels of Ted Lasso Season 1 with a hint of Tiger King Season 1 showmanship). Regardless, it gave me a bird’s eye view of Bancroft’s world.

Bird’s Eye View from The Book of the Fair (1893).

Bird’s Eye View from The Book of the Fair (1893).

With the library’s resources at my fingertips, I graduated from The Book of the Fair to studying Bancroft’s magnum opus, the previously mentioned The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Works was notably criticized for Bancroft’s use of the ‘German Method’, the collection was highly debated because he tasked his subordinates with writing his historical volumes without credit or citation of the actual authors. In a twist of fate, he was even roasted by fellow historians for using this method at the 1893 World’s Fair.

Bancroft built his publishing empire and compiled the stories of the biggest names in the American West. He democratized endless volumes of knowledge, turning books into an empire, á la a Jeff Bezos of the 19th century, sans the rocketship, but sharing the inclination to wear a cowboy hat. Historian John Walton Caughey praised Bancroft when he stated “A prodigious historian he certainly was; generations hence he may loom up as the most significant figure that the West has produced.” Historian of modern California Kevin Starr equally praised Bancroft’s effort when he said “The fundamental genius of Hubert Howe Bancroft lies in the fact that he envisioned such a comprehensive history, assembled its materials, set researchers and writers to work, and produced, published, and marketed History with a Capital H he had emblazoned over the entrance of the History Building be built on Market Street”. Bancroft’s Works was an enormous feat and would be the students’ first introduction to Bancroft– it was our American West Nuremberg Chronicles. Our American West Wikipedia.

“So he did a good thing, Mr. Skomba?”

“He added to our collective understanding. A good thing indeed.”

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie so eloquently put it, there’s “danger in a single story.” Out of the volumes that have been confirmed as being authored by Bancroft, two of them deal with ‘Popular Tribunals.’ This is the second piece of the case study. Scholarship in the past decade by Dr. Lisa Arellano suggests that Bancroft uses the two volumes on Popular Tribunals to valorize what essentially equates to a lynch mob. Such executions are American schema via our spaghetti westerns. It was not until I interfaced with the scholarship that I could see the pattern of the tribunals. They were not Popular Tribunals but rather “Popular Lynch Mobs.” They preyed on non-white Californians and carried out outlaw executions with little to no factual evidence.

Furthermore, a third title that was also confirmed to have been written by Bancroft titled Literary Industries, includes derogatory comments on women in the literary industry:

“Several women were also employed upon these voyages. I know not why it is, but almost every attempt to employ female talent in connection with these industries has proved a signal failure. I have to-day nothing to show for thousands of dollars paid out for the futile attempts of female writers…If she have genius, let her stay at home, write from her effervescent brain, and sell the product to the highest bidder.”

Women, most notably Francis Fuller Victor (who is credited for writing the The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Oregon: Vol. II, 1848-1888) after Bancroft’s death) dictated, edited, and flatout wrote Bancroft’s Works.

“Can we trust his history, Mr. Skomba?”

“People are complex.”

Upon his death, Mr. Bancroft donated his library (the largest on the West Coast) to the University of California. The library at the University of California-Berkeley still bears his name. A copy of Mr. Bancroft’s correspondence with Andrew Carnegie can be found in the New York Public Library Brooke Russell Astor rare books reading room. He notes his agreement with Carnegie’s drive for philanthropy and endorses donating to worthy causes. His envoys to Mexico City or Europe were driven by his desire to build his repository of Western sources for posterity.

“So he was generous, Mr. Skomba?”

“Would you donate your life’s work?”

I originally wrote off the valorization of Popular Tribunals as a base intersection of dime novels and academia. History is not convenient–stereoscopic historical research shows us other secondary sources bring the race theory dilemma into focus. In Gilman M. Ostrander’s 1958 article titled ‘Turner and the German Germ Theory’ Ostrander quotes from Bancroft’s fourth and final self-authored volume of Works titled ‘Essays and Miscellany’ in order to compare him to the notorious Frontier Thesis presented by Fredrick Jackson Turner:

Unlike Turner’s essay, this earlier account by Bancroft was overtly, in fact jubilantly, race-conscious, as well as altogether carefree in its generalization… Both men were influenced alike by the intellectual currents of a day when Americans were possessed of boundless confidence in the race, the nation, the section and the individual, and when the inherent superiority of the Anglo-Saxon or the Germanic or the Teutonic or the Aryan race was a common intellectual assumption of the day.

“So he was a racist, Mr. Skomba?”

“He was a complicated historical figure worth studying. What did we learn in the process?”

With Bancroft, complexities abound. I believe that the most meaningful historical thinking happens in these messy edges of uncertainty and uncomfortableness. Discerning whether to deconstruct or assign value to historical narratives is a spiraling skill for both teachers and students. My intentions that drove this curriculum were never focused on making the students experts on H.H. Bancroft but rather equipping critical consumers of established history. I did not want or need my students to be experts on Bancroft’s biography. Instead, Bancroft’s case study gave us a worthy problem- a vehicle instead of a destination. I want them to test every claim they interact with, analyze context, and find out who wrote their textbooks. My time as a Neville-Pribram Fellow at Smithsonian Libraries (now Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) gave me the space and the energy to take off the practitioner hat to dive beneath the waves and spend time swimming in the deep currents. Doing such work might be as bumpy as the 19th century Wagon Trains, but once educators master the trail, they can help students predict what’s next.

The next great democratizer of information-the next H.H. Bancroft-just might be sitting in the second row of your classroom. I might have already taught her:

Further Reading:

Arellano, Lisa. Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation (2012).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe, The Book of the Fair (1893).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. Literary Industries: Chasing a Vanishing West (2013).

Bancroft, Hubert Howe, The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft (1882).

Caughey, John Walton. “Hubert Howe Bancroft, Historian of Western America.” The American Historical Review 50, no. 3 (1945): 461–70.

Johnson, Rossiter. A history of the World’s Columbian exposition held in Chicago in 1893 (1897-1898).

McNeill, William H. “Mythistory, or Truth, Myth, History, and Historians“, The American Historical Review, Volume 91, Issue 1, February 1986, Pages 1–10.

Morgan, Lewis H. Review: [Untitled], The North American Review 122, no. 251 (1876): 265–308.

Ostrander, Gilman M. “Turner and the Germ Theory.” Agricultural History 32, no. 4 (1958): 258–61.

Summer 2022 Internships Opportunities with Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

We’re excited to announce a new round of internships for Summer 2022. These opportunities provide hands-on experience in a range of subject areas and are open to both undergraduate and graduate students. Each unique project offers a chance to explore current topics in archives, libraries, and information science and learn from experienced Smithsonian Libraries and Archives staff.

Most are virtual/remote opportunities, but one project includes on-site work in our American Art and Portrait Gallery Library. All include a stipend. The application deadline is February 13th, 2022.

Programs include:

- Education: For students interested in museum education or similar fields, this intern will assist in creating educational resources from our collections.

- Kathryn Turner Diversity and Technology Internship: A special opportunity for students attending Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

- Professional Development: For a current MSLIS student or recent grad, experience evaluating and working with Library of Congress Subject Headings.

- Summer Scholars: Three projects for both undergraduates and grad students, including opportunities to work with art and artists files, web and social media archiving, and oral histories.

Learn more about academic appointments and related policies on our Internship and Fellowship page. Curious about the work of past interns? Read more about their experiences.

ICYMI: Five Most Popular Posts of 2021

There was plenty of news in 2021 and most of it was, well, not great. So, you’ll be forgiven if you overlooked an article or two on this very blog. In case you missed them, here are five of our most popular blog posts of the past year. This assortment highlights interesting collection items as well as the important work of our staff. As we say goodbye (and good riddance?) to 2021, we invite you to cuddle up by the fireplace and catch up.

Sleuthing Captain America’s Shield

Did you know that our Ask A Librarian service answers hundreds of questions from Smithsonian researchers and the general public throughout the year? Recently, an inquiry about a fictional scenario had staff investigating real-life Smithsonian policy. Alan Katz explains “Can they do that with Captain America’s shield?”.

Shield used by Chris Evans as Captain America in Captain America:The Winter Soldier, National Museum of American History 2018.0107.01.

Shield used by Chris Evans as Captain America in Captain America:The Winter Soldier, National Museum of American History 2018.0107.01.

Libraries Then and Now: The Ideas We Share

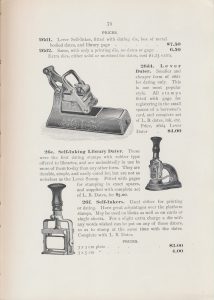

Our monthly trade literature feature often brings back fond memories via vintage catalogs, and this post really got librarians and library users right in the feels. Alexia MacClain explores borrower cards, date stamps, and other classic supplies from Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899).

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899), page 79, Lever Dater, Self-Inking Library Dater, and Self-Inkers.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899), page 79, Lever Dater, Self-Inking Library Dater, and Self-Inkers.

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles: January Edition

Our series of digital jigsaw puzzles, all based on images in our collections, have been popular throughout the pandemic. We kicked off 2021 with an assorted set of snowy scenes and bright patterns, as satisfying to put together today as they were a year ago.

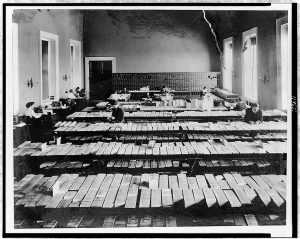

Exploring Bias and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Subject headings are important tools for library classification. But the terms used can sometimes leave gaps or become outdated, particularly when it comes to topics of diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion. Intern River Freemont describes their experience researching and drafting proposals to update Library of Congress Subject Headings with the goal of improving accuracy and inclusivity.

People working in Card Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [Between 1900 and 1920] [Photograph]. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97513719/.

People working in Card Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [Between 1900 and 1920] [Photograph]. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97513719/.

Introducing Information Literacy Collections in Learning Lab

Launched in August to coincide with the Smithsonian’s 175th anniversary, our newest resources in Smithsonian Learning Lab are dedicated to improving information literacy. Sara Cardello discusses this series of interactive, online collections that are intended to help users think critically about how they identify, find, evaluate, and use information effectively.

Giftable Adopt-a-Books for the Holiday Season

Did you know you can honor friends and family, enable important research, and skip the mall this holiday season? Adopting an item from the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is a unique way to celebrate your loved ones while providing essential funding to support our work. Whether your gift funds the preservation of volumes from hundreds of years ago, the purchase of new titles for our collection, or increased accessibility to items on our shelves, your adoption enables all that we do.

While you can’t wrap up your adopted books and put them under the tree, your purchase will be honored with a digital bookplate and the warm feeling of knowing you’ve helped further critical work at the Smithsonian Institution. From our list of adoptable items, we think you’ll find something for just about everyone on your list.

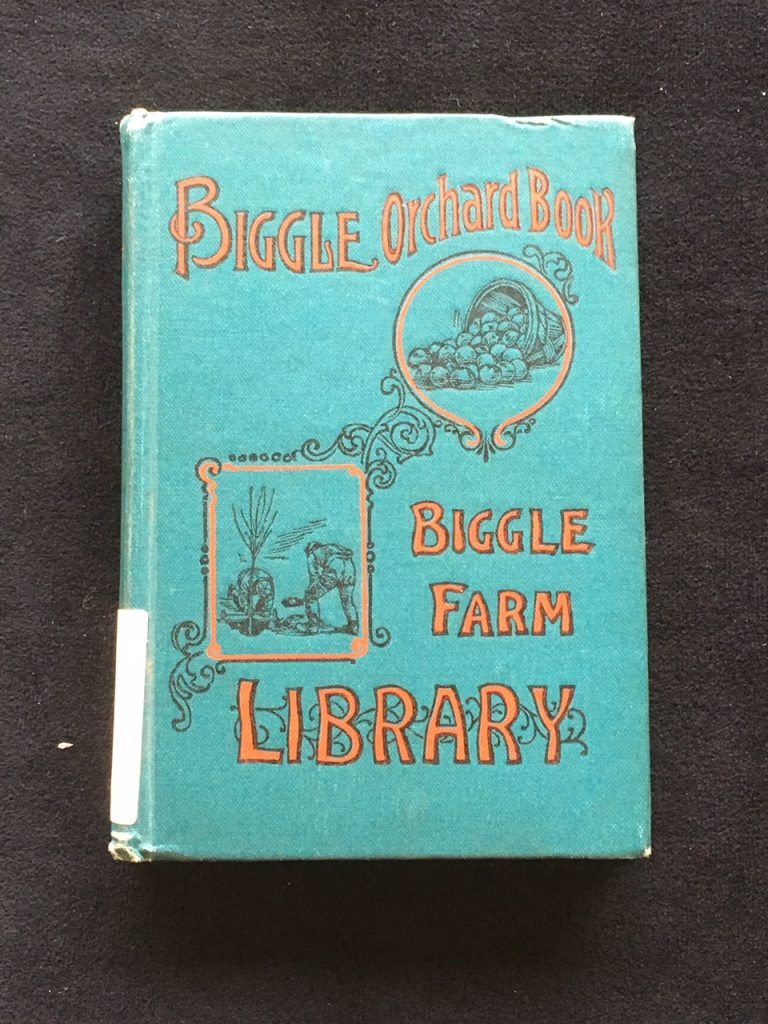

For the Green Thumb:

Biggle orchard book: fruit and orchard gleanings from bough to basket

By Jacob Biggle. Philadelphia: W. Atkinson Co., 1911.

Cover, Biggle orchard book: fruit and orchard gleanings from bough to basket (1911).

Cover, Biggle orchard book: fruit and orchard gleanings from bough to basket (1911).

This pocket-sized book is part of the Biggle Farm Library, a collection of volumes that cover a gamut of agricultural topics from gardening to beekeeping to raising pigs and horses. The author, Jacob Biggle, states that his book “aims to tell the inquiring reader just what he or she needs to know—no more, no less.” The book starts with advice about the proper planning and siting of an orchard where he advises putting on “your thinking cap” and taking your time. He also covers planting and pruning trees, pest and weed control, picking, and packing fruit for market.

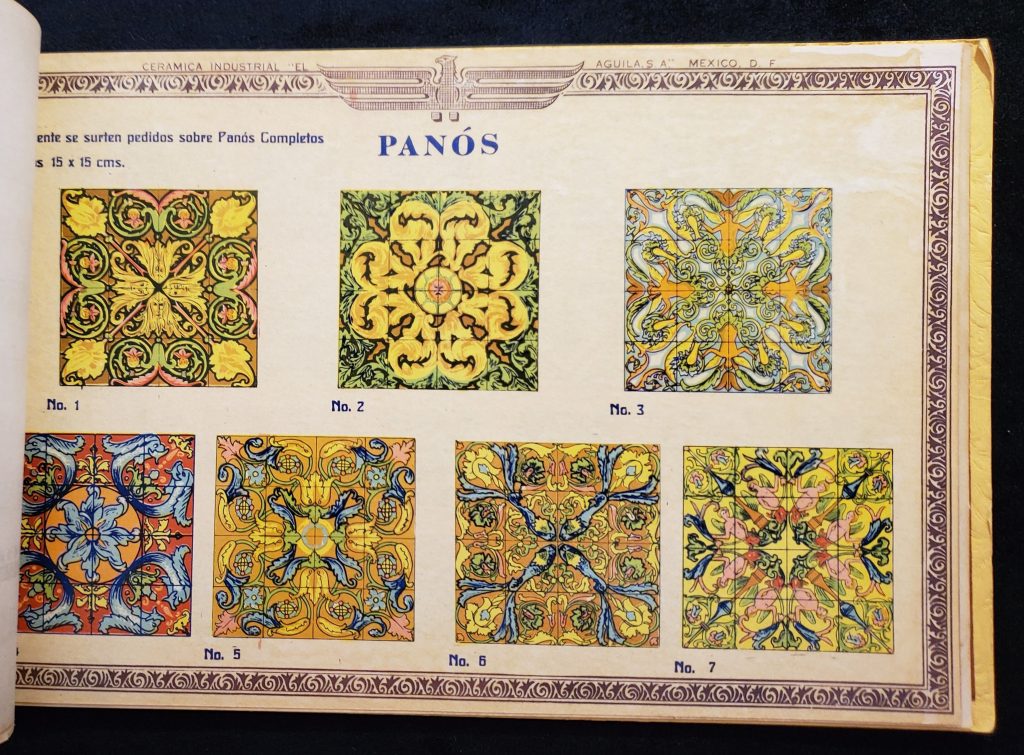

For the Interior Design Enthusiast:

Ceramica Industrial “El Aguila, S.A.” : hecho en Mexico

By Ceramica Industrial “El Aguila, S.A.”. México, D.F. : Ceramica Industrial “El Aguila, S.A.”, [1941].

“Paños”, Ceramica Industrial “El Aguila, S.A.” : hecho en Mexico, [1941].This catalog is from the Mexican “Eagle Industrial Ceramic Co.” With beautiful full-color chromolithographic illustrations of the tiles, it demonstrates the various uses of their designs for fountains, seating, open spaces, and other decorative design applications, as well as samples of individual tile patterns. It includes examples of classic Arabesque, Moorish, and Mediterranean majolica tile designs. The forward and introduction discuss the history and tradition of tiles and their use in Mexico, describing them as “the combination of bricks and glass…the tiles of old Europe came to our land with colors of the skies, clouds, seas, and suns…they stand tall today in our homes and parks.”

“Paños”, Ceramica Industrial “El Aguila, S.A.” : hecho en Mexico, [1941].This catalog is from the Mexican “Eagle Industrial Ceramic Co.” With beautiful full-color chromolithographic illustrations of the tiles, it demonstrates the various uses of their designs for fountains, seating, open spaces, and other decorative design applications, as well as samples of individual tile patterns. It includes examples of classic Arabesque, Moorish, and Mediterranean majolica tile designs. The forward and introduction discuss the history and tradition of tiles and their use in Mexico, describing them as “the combination of bricks and glass…the tiles of old Europe came to our land with colors of the skies, clouds, seas, and suns…they stand tall today in our homes and parks.”

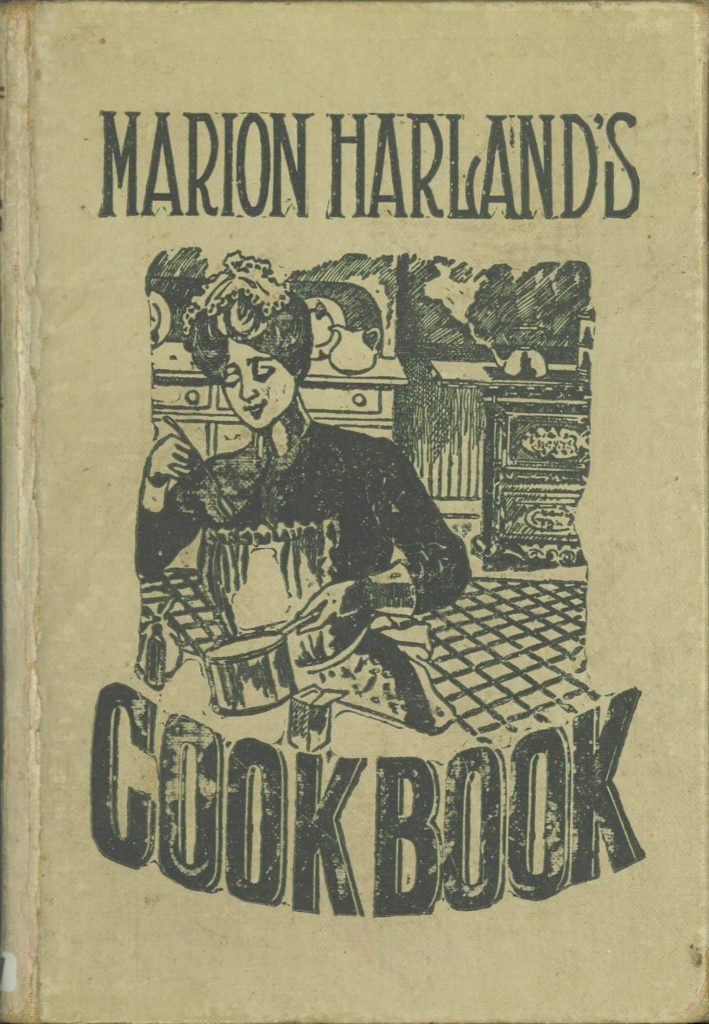

For the Amateur Chef:

Marion Harland’s cook book of tried and tested recipes

By Marion Harland (1830-1922). Chicago, IL: L.W. Walter Co., 1907.

Cover, Marion Harland’s cook book of tried and tested recipes (1907).

Cover, Marion Harland’s cook book of tried and tested recipes (1907).

There were few writers of the 19th century as prolific or variegated as Mary Virginia Tehune, who was best known by her nom de plume Marion Harland. Her dozens of fiction books appealed to women readers throughout America through idealized domesticity, sensational yet tasteful romance. But her non-fiction books, covering all aspects of the care of the home, made her a literal household name, with her volumes resting on many homemakers’ shelves for ready reference. The Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex’s copy is one such example, annotated in several hands from the early 20th century describing planned meals, clarifying techniques, and the annotators’ special twist on Harland’s recipes.

For the Art Lover:

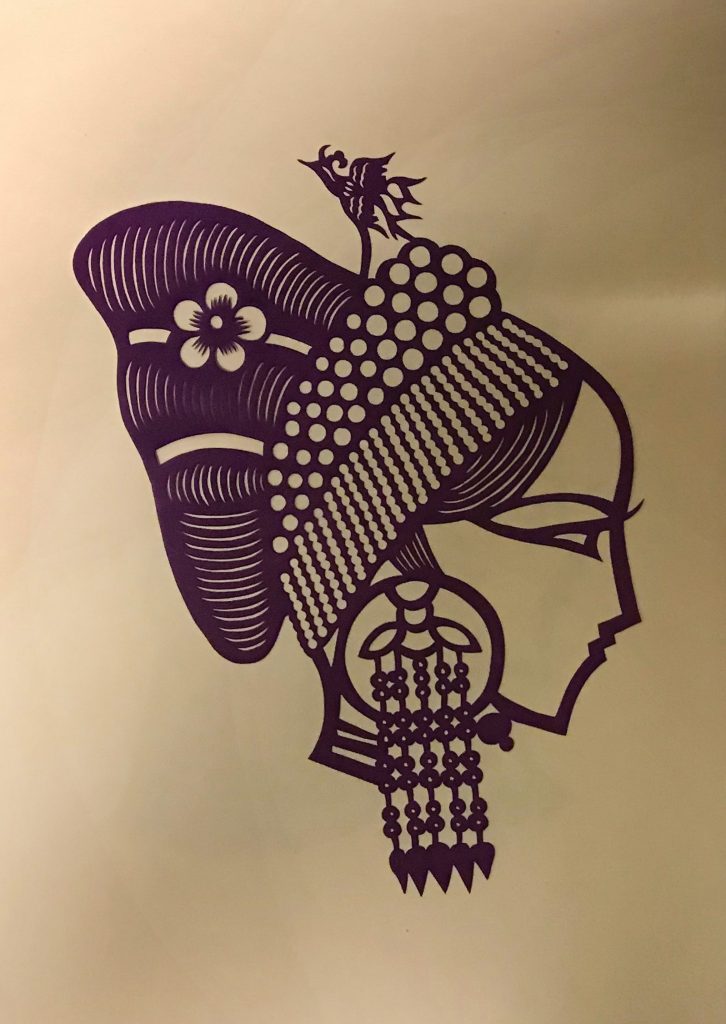

Zhongguo shao shu min zu fu nu tou shi [Chinese minority women headdresses]

By He, Hongyi . [S.l.]: s.n., 200?.

Tu nationality illustration, Zhongguo shao shu min zu fu nu tou shi (200?).

Tu nationality illustration, Zhongguo shao shu min zu fu nu tou shi (200?).

Chinese folk papercuts are usually treated as anonymous art, differentiated only by local styles. The study of these papercuts may be able to tell us something about local minority art and culture in China and studying the artists can help understand regional styles and the subject matter. The author and artist of this book, Hongyi He, is a professor at the School of Literature and Journalism of South-Central University for Nationalities and the director of the Folk Literature and Foreign Literature Department. She is also an accomplished folk artist with awards from the Chinese Folk Artists Association

Beginning in 2009 as an initiative centered on preserving rare volumes, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Adopt-a-Book program has grown into a thriving circle of supporters and staff passionate about the power and legacy held by books. Book adoptions directly support the purchase of new, relevant materials to further important research and programs, facilitate increased access to our collection, and fund the preservation of items in our collection. Curious about the full impact of our Adopt-a-Book program? Explore “The Lasting Impact of Your Book Adoption”.

Holiday Cooking with Hannah Glasse

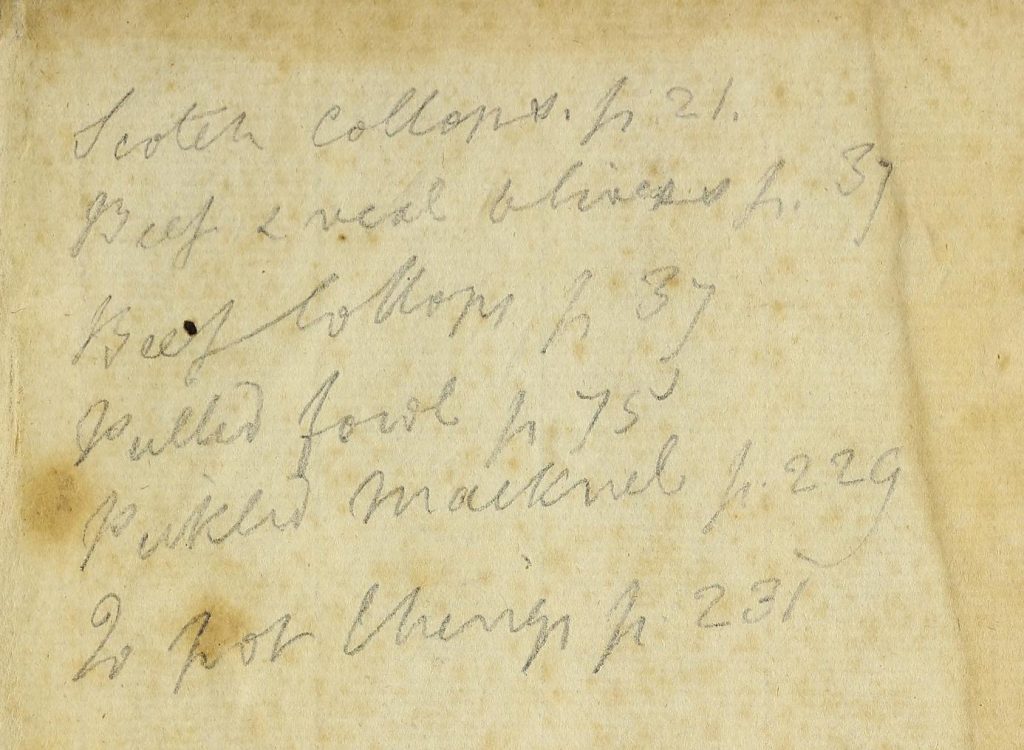

The holiday season has kitchens humming around the world, whether it’s churning out a favorite cookie recipe or prepping a celebratory meal with loved ones. In the 1700s, kitchens in England regularly consulted Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy for tried-and-true recipes. Among Glasse’s readers was a food lover near and dear to our hearts: Smithsonian founder James Smithson. Whether he knew it or not, Smithson had a bit in common with Glasse. Both were the illegitimate children of privileged Northumberland fathers, and each would leave a lasting cultural legacy.

Smithson’s copy of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy can be found in our Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Natural History Library. This edition, printed in 1770, is one of 124 titles from Smithson’s private book collection which came to the Institution with his personal belongings. Our copy contains several notes in Smithson’s own hand. Of special interest to us is the list of recipes noted on the back pastedown, such as “Scotch Collops”, which may have been Smithson’s favorites.

Rear pastedown, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Rear pastedown, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

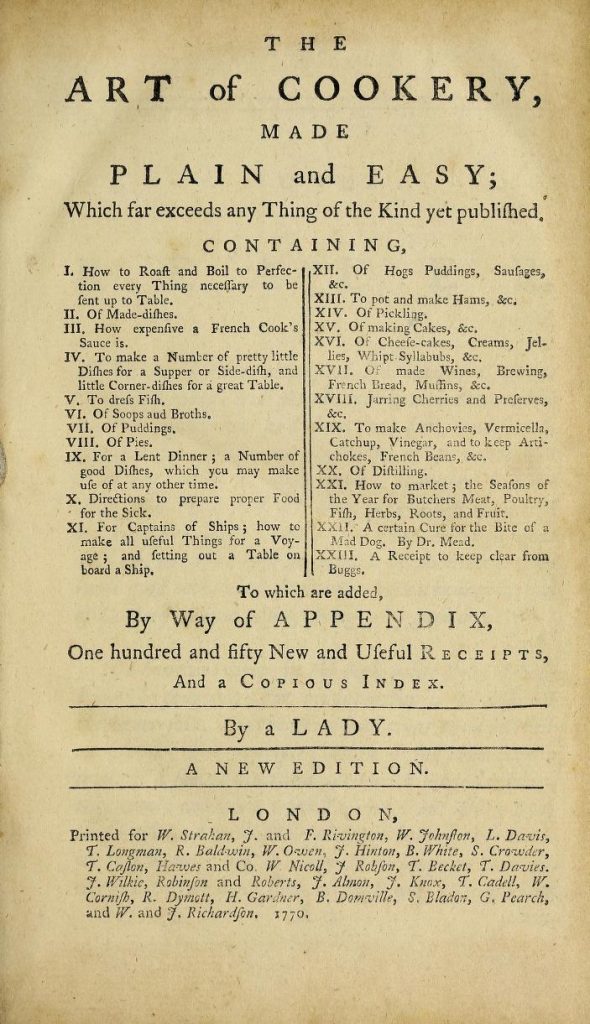

When it was first published in 1747, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy was not originally attributed to Glasse but rather simply to “a Lady”. What set Glasse’s work apart from other “cookery” books of the time was the intended audience. Glasse hoped to reach cooks of the “lower sort” not well-trained chefs in grand houses. She purposely avoids instruction in the “high polite style” and eschews contemporary French terms in favor of more recognizable phrases, like “little pieces of bacon” instead of “lardoons”, with an emphasis on practicality and frugality.

Title page, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Title page, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Though many of the recipes were first printed in other sources, Glasse’s work is notable for compiling so many recipe options and methods, and in some cases simplifying instruction. According to Anne Willen’s account in Great cooks and their recipes, Glasse’s book became one of the most successful publications of the 18th century – reproduced in over 20 editions by 1800. But despite the book’s popularity, Glasse filed for bankruptcy in 1754. She did write at least two additional books, but little is known about the end of her life. She died in 1770.

Thanks to our Adopt-a-Book program and generous donor John H. Dick, our copy of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy has received conservation treatment, been fully digitized, and is available online. Senior book conservator Katie Wagner describes the book and her experience working with it in this YouTube video:

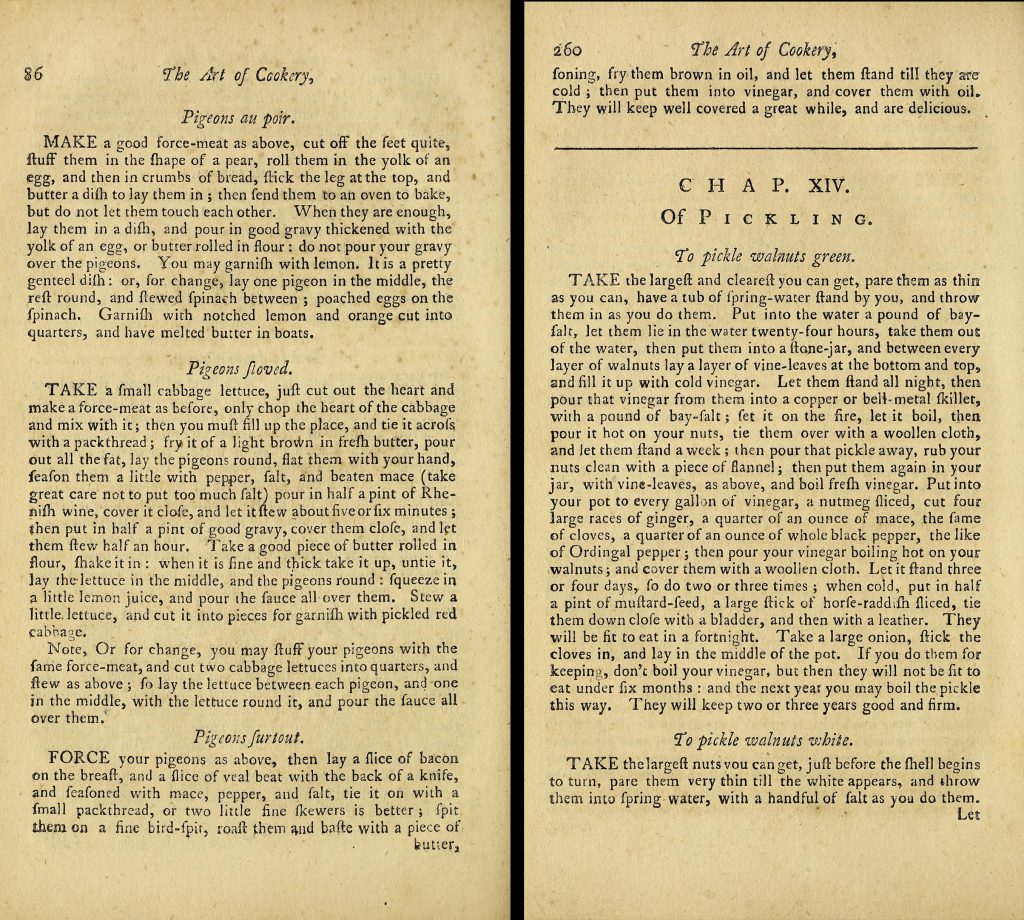

Flipping the digital pages will leave you absolutely in awe of not only the time and effort that went into an average Georgian-era meal but also the odd preparations and food pairings that might confuse a modern palate. Eels, rabbits, and pigeons were popular sources of protein. And from oysters to walnuts, there were few foods that Georgian Era cooks were afraid to pickle. Glasse’s 1747 edition is thought to contain the first published recipe for curry written in English, previously highlighted on the blog by Daria Wingreen. Daria also experimented with Glasse’s gingerbread (cookies), which might have been a favorite of James Smithson himself.

Left: Page 86. Right: Page 260. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Left: Page 86. Right: Page 260. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

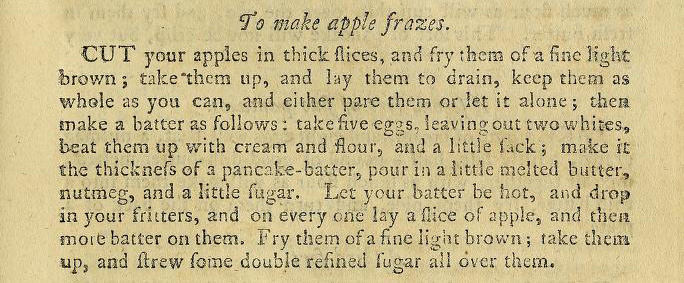

‘Tis the season to fire up the stove and oven, so we couldn’t resist sharing this vintage cookbook without giving a new recipe a try. Here is a tasty recipe for “apple frazes” from The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Frazes are a sort of eggy pancake – perfect for your holiday brunch. The ingredient “sack” refers to a fortified wine, which is similar to sherry. While Glasse recommends topping them with sugar, our testers (aged 9 and 12) preferred dousing them in maple syrup. They would also pair well with a cup of coffee brewed using James Smithson’s own “improved method”.

“To Make Apple Frazes”. Page 159, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

“To Make Apple Frazes”. Page 159, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Apple Frazes

Makes about six

Ingredients:

- A few tablespoons butter, divided

- 1 large apple, cored and cut into thick circular slices

- 3 whole eggs, plus two yolks

- ½ c. cream

- ½ c. flour

- 1 tsp. sherry

- ½ tsp. nutmeg

- ¼ c. sugar

Instructions:

- Fry the apples in about 1 tbs of butter, until brown and softened.

- Beat eggs and combine with the rest of the ingredients, including about a tablespoon melted butter.

- Pour a small amount of batter (less than ½ c.) into pan. Place apple slice on top. Pour additional batter over pancake to cover apple. Flip when almost cooked through.

- Serve warm with a sprinkling of sugar or maple syrup.

Further Reading:

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1770).

Sherman, Sandra. “Hannah Glasse”, Culinary biographies : a dictionary of the world’s great historic chefs, cookbook authors and collectors, farmers, gourmets, home economists, nutritionists, restaurateurs, philosophers, physicians, scientists, writers, . . . (2006).

Turner, Steven. “A Coffee Break with James Smithson” (2021).

Willen, Anne. Great cooks and their recipes (1992).

Wingreen, Daria. “Cooking from the Collections: James Smithson’s Gingerbread and more” , (2011).

Wingreen, Daria. “Smithson’s Cookbook: English Curry” (2012).

The Varied and Artistic Uses of Decorative Tissue Paper

That time of year is upon us. The season when we see lots of gift bags stuffed with brightly colored tissue paper. The simple act of fluffing a piece of tissue paper and placing it in a bag seems to brighten any present. But how about using tissue paper to create art? This trade catalog from over a century ago might spark our creativity.

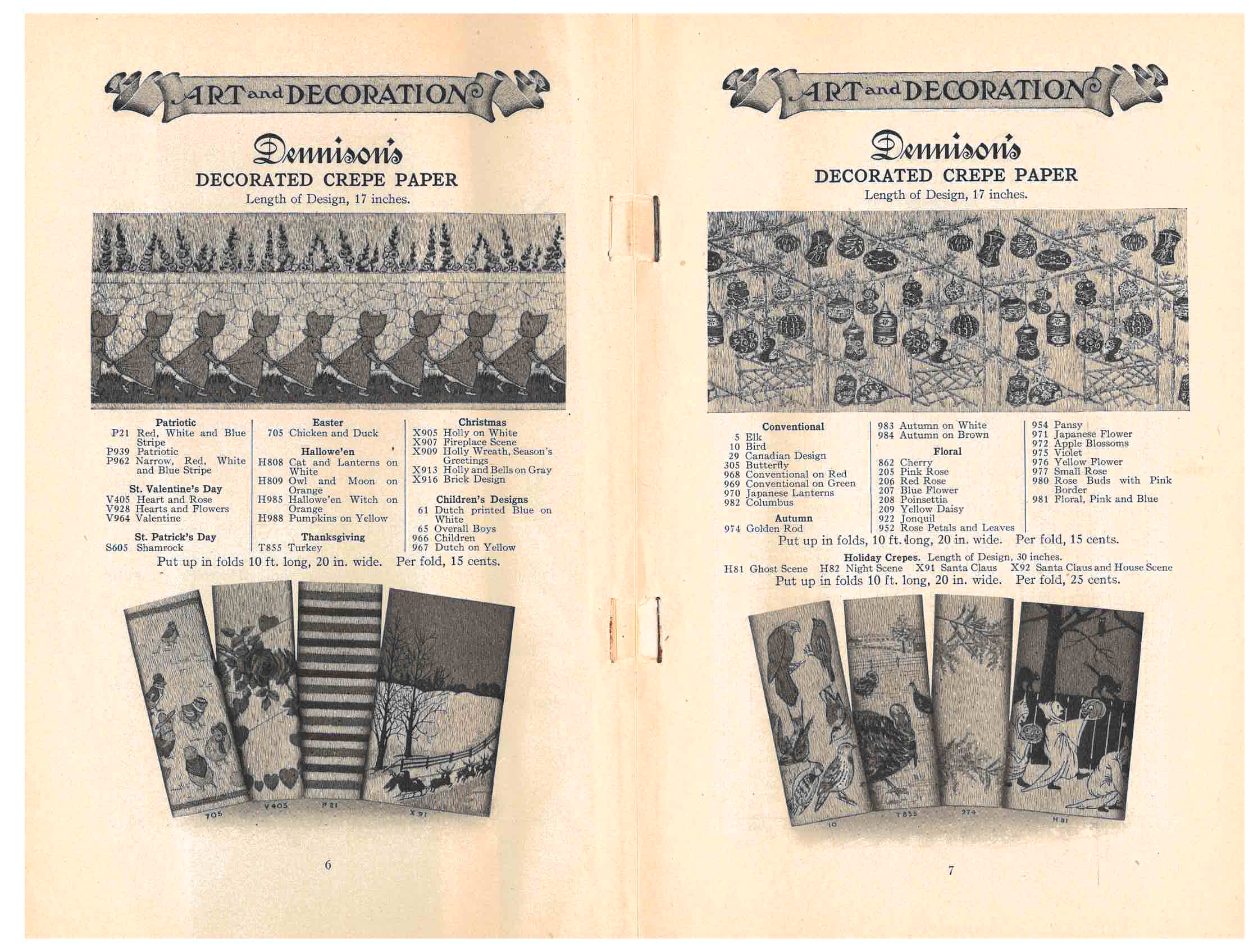

The catalog is titled Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914) by Dennison Mfg. Co. In 1914, at the time this catalog was printed, there were Dennison stores or offices throughout the United States and in Canada, London, Berlin, and Buenos Aires.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), title page.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), title page.

Dennison Mfg. Co. sold crepe paper, decorated paper, and tissue paper among other things. Their tissue paper was available in 134 shades and colors. They also sold crepe paper, including decorated crepe paper in a variety of holiday, seasonal, or floral designs and patterns. Besides decorations, these materials could be used for creating art. Personal instruction for such things as making flowers out of crepe and tissue paper was provided at their stores in the Art Departments.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 6-7, Dennison’s decorated crepe paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 6-7, Dennison’s decorated crepe paper.

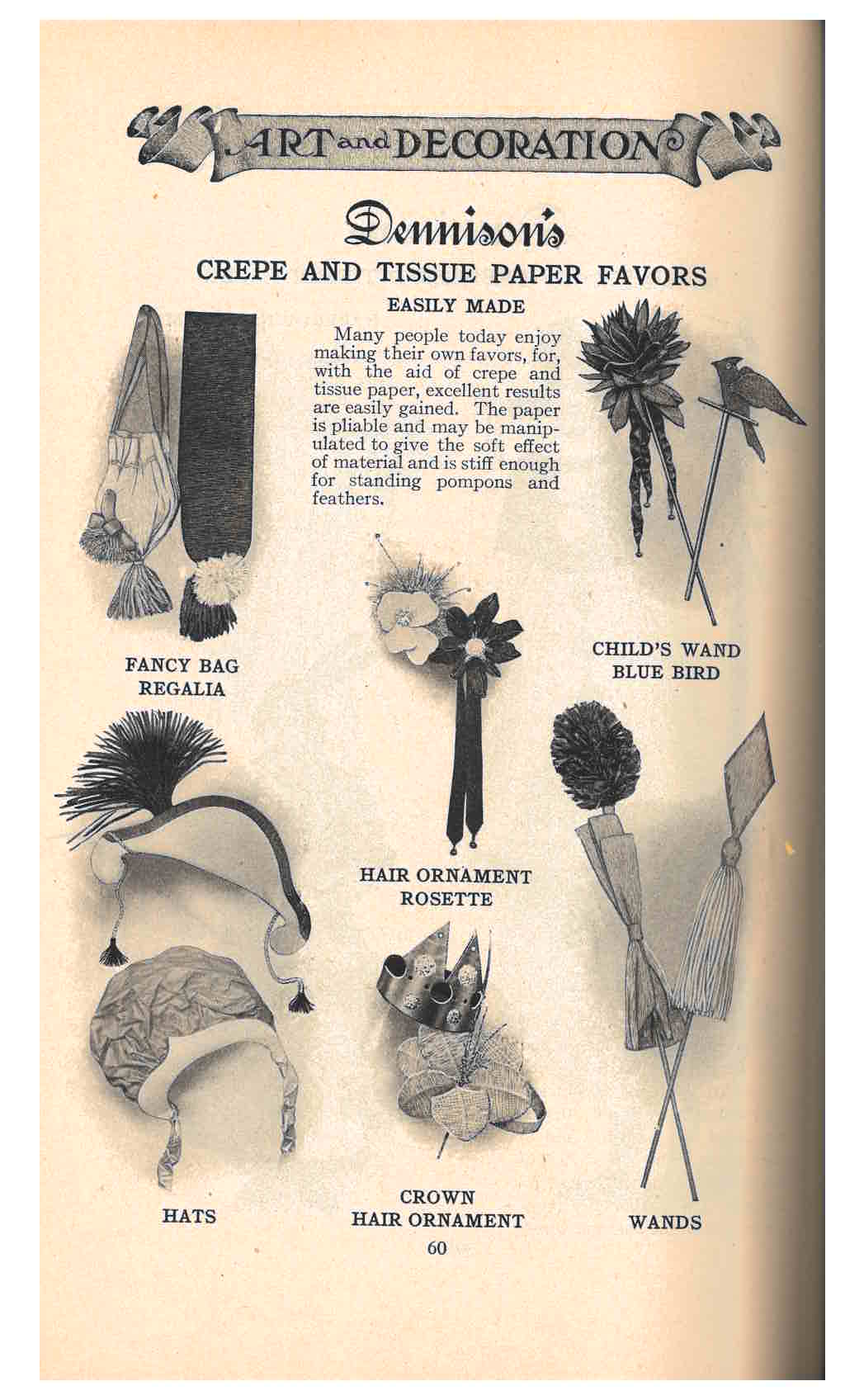

As the catalog mentions on page 3, it is “primarily a book of suggestions.” The ideas for using crepe and tissue paper are numerous, everything from party, fair, and parade decorations to costumes to creating artwork.

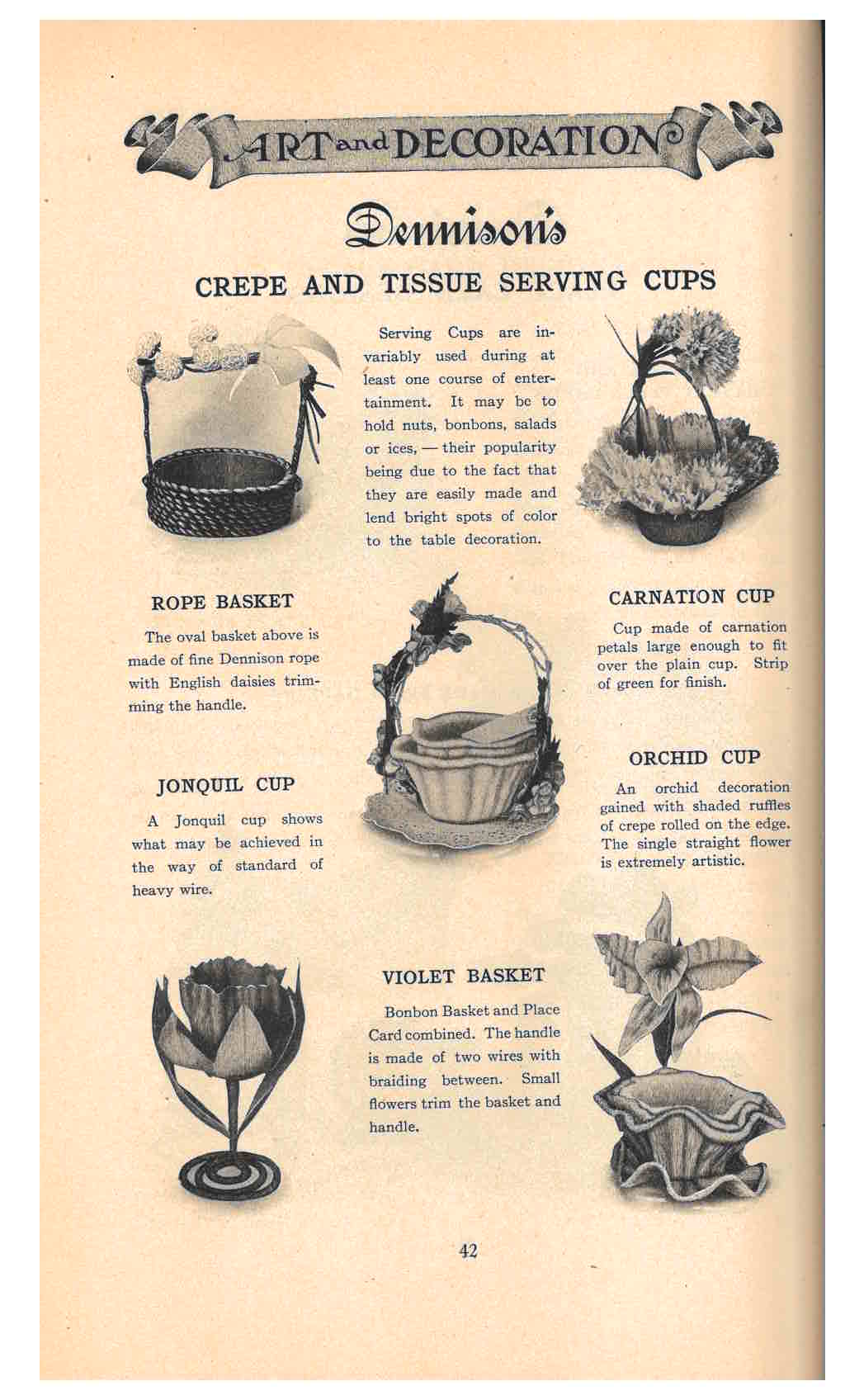

To add a festive touch, a host in the early 20th Century might have created party favors or fashioned crepe or tissue paper flowers to decorate a serving dish. The choices are many and varied. Perhaps a rope basket with daisies along the handle, serving cups decorated with carnation petals or orchids, a basket trimmed with violets, or a Jonquil serving cup, all illustrated below. Handmade party favors might have included hats, crowns, hair ornaments, or even a child’s wand, also shown below.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 42, Serving cups and baskets decorated with crepe and tissue paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 42, Serving cups and baskets decorated with crepe and tissue paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 60, crepe and tissue paper party favors.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 60, crepe and tissue paper party favors.

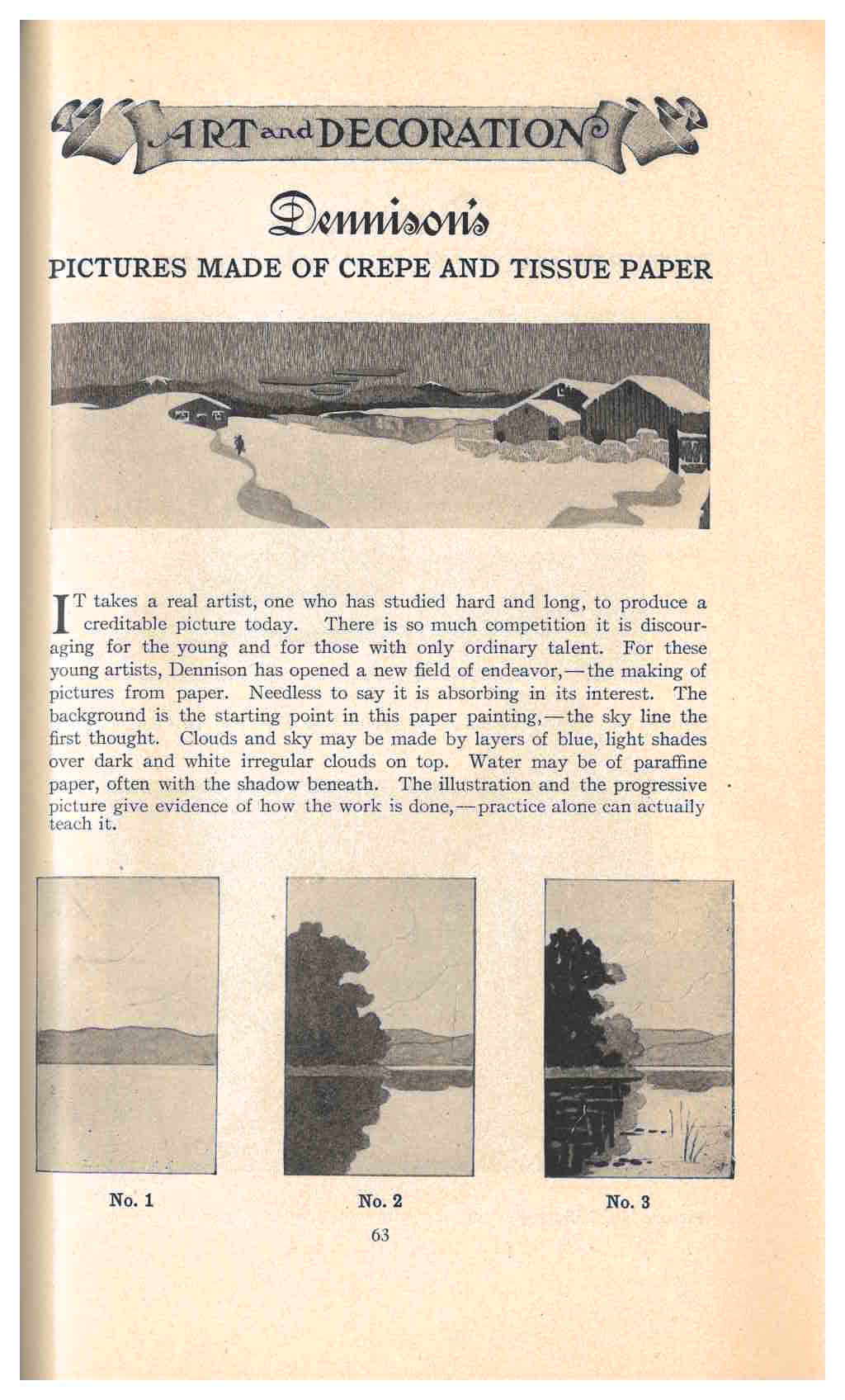

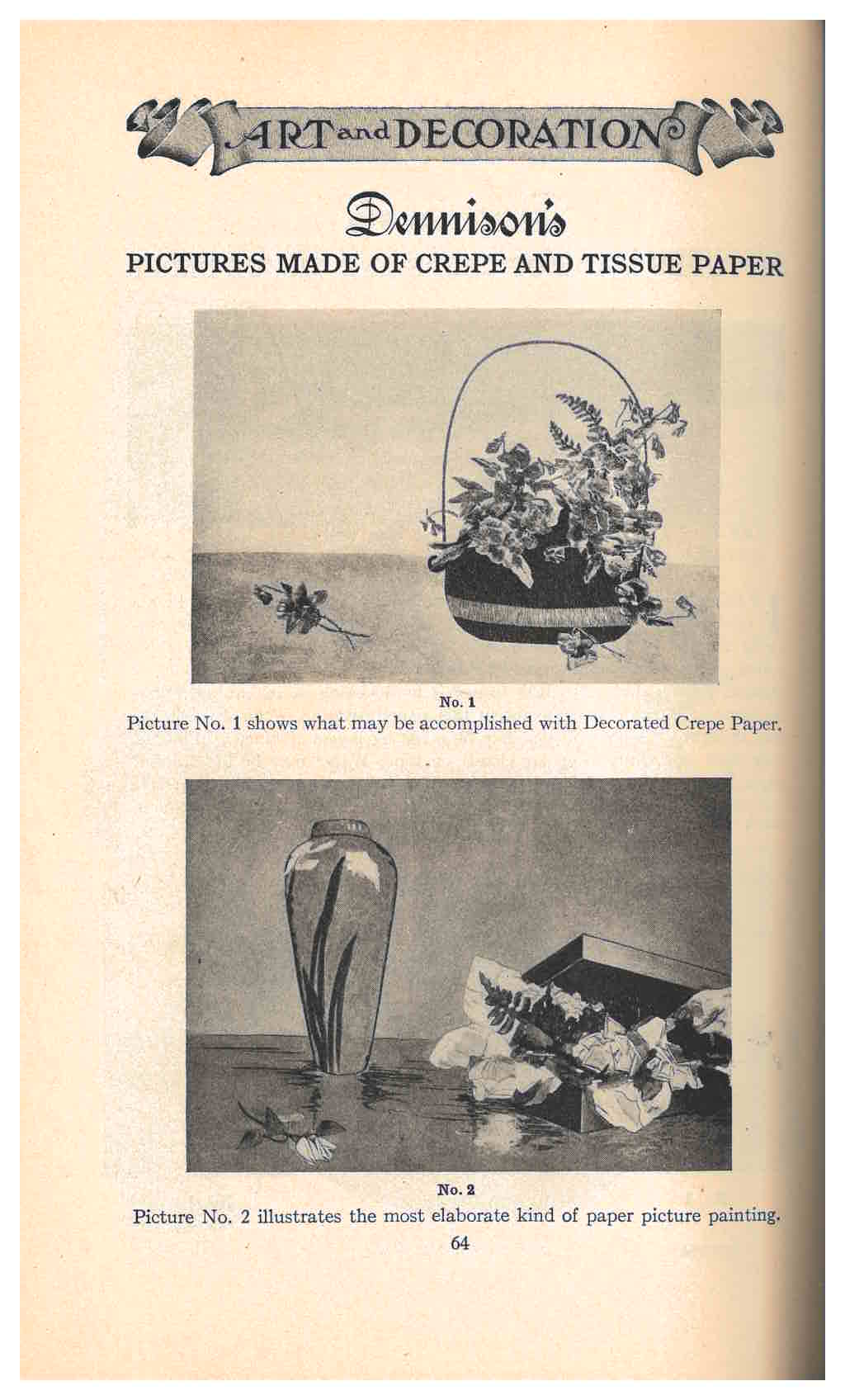

Another creative use of crepe or tissue paper is artwork. Pictures or scenes, such as these winter and natural landscape ones below, can be made out of paper. The catalog suggests starting with a background and then layering paper on top of each other. The sky might be created by layering shades of blue paper, lighter shades over darker shades, and adding white irregularly shaped paper for the clouds. The examples below show the progression of layering crepe or tissue paper to create a landscape picture or the possibilities of making a more elaborate still life creation.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 63, winter and natural landscape pictures created from crepe and tissue paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 63, winter and natural landscape pictures created from crepe and tissue paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 64, still life pictures created from crepe and tissue paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), page 64, still life pictures created from crepe and tissue paper.

When thinking about art and tissue paper, creating paper flowers might come to mind. This early 20th Century catalog or “book of suggestions” incudes a section for just that type of craft. It first advises that one should be familiar with the appearance of the specific flower in nature before creating it out of crepe or tissue paper. But it also adds that the unique taste and judgement of each person is important.

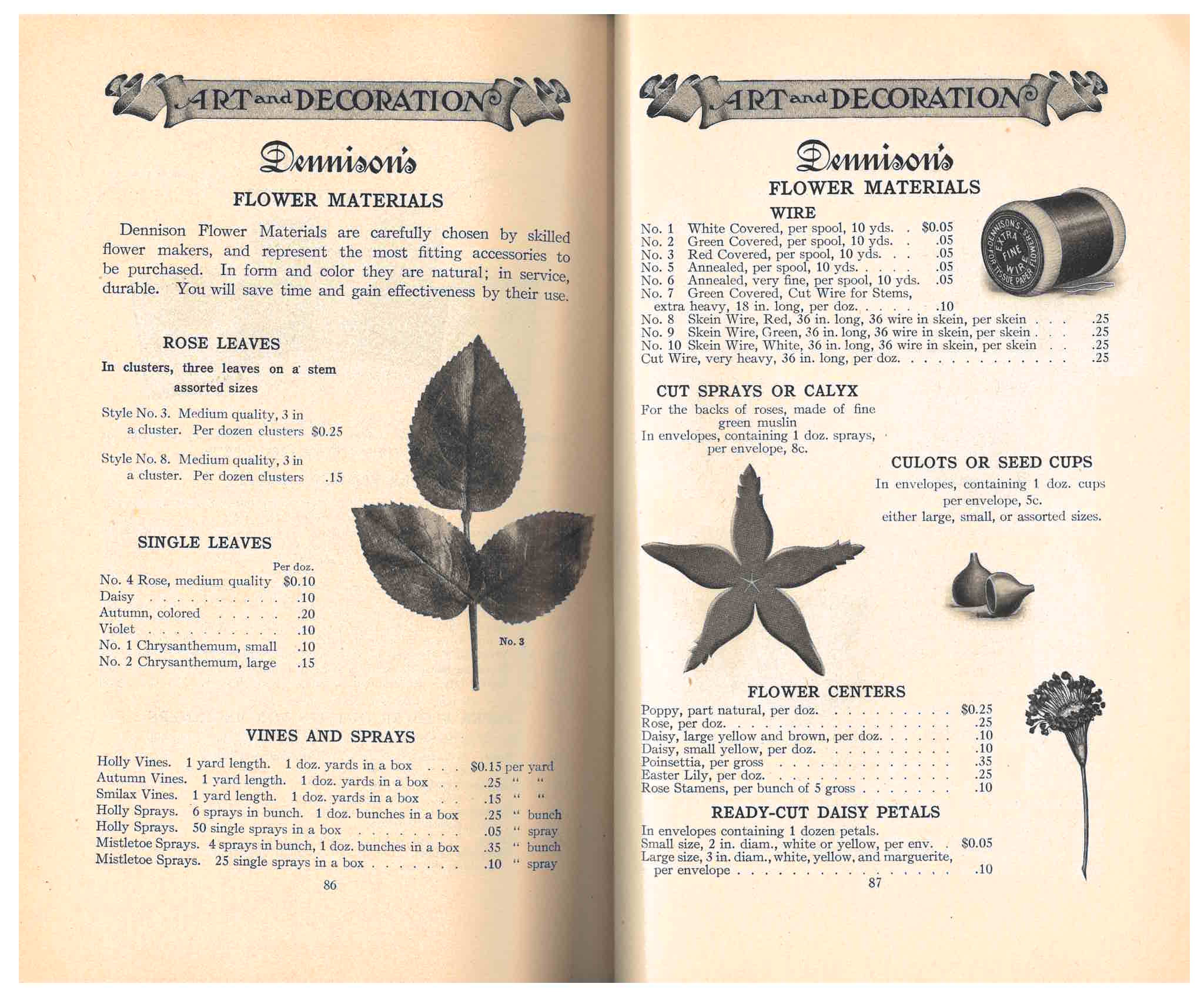

The section begins with general directions before proceeding to specific directions and patterns for particular flowers. It also includes a few pages showing “Flower Materials.” These are things such as leaves, vines and sprays, calyx, seed cups, flower centers, wire, and even ready-cut daisy petals. The catalog mentions that using some of these supplies when making paper flowers will save time and energy.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 86-87, flower materials, including rose leaves, single leaves, vines and sprays, wire, cut sprays or calyx, culots or seed cups, flower centers, and ready-cut daisy petals.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 86-87, flower materials, including rose leaves, single leaves, vines and sprays, wire, cut sprays or calyx, culots or seed cups, flower centers, and ready-cut daisy petals.

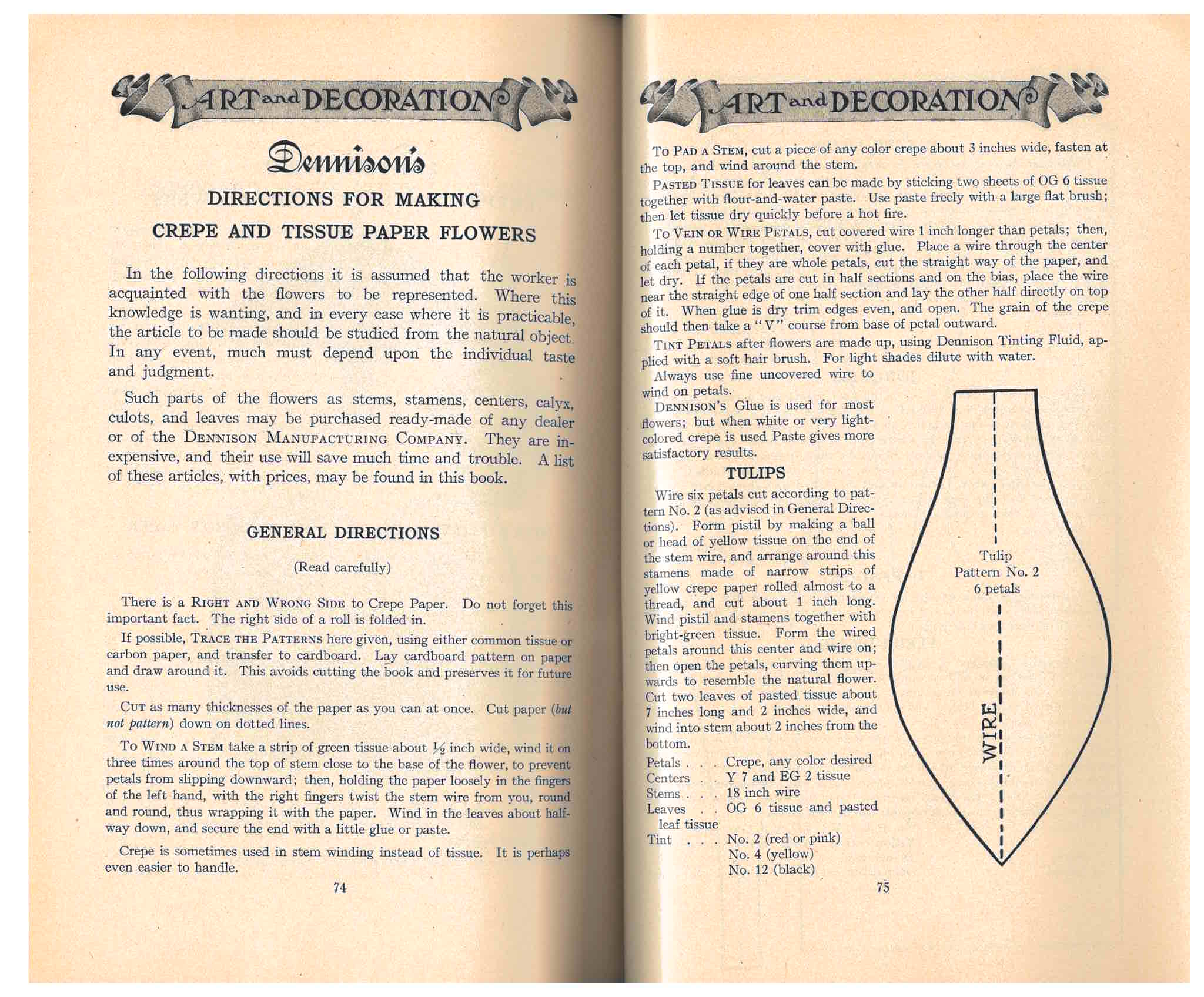

The General Directions, shown below, begin with a lesson on the “RIGHT AND WRONG SIDE to Crepe Paper.” According to these directions, the “right side” is the side of the roll when folded in. It suggests tracing the patterns onto tissue paper or carbon paper and then transferring them to cardboard. Next, the cardboard pattern can be laid on the desired tissue paper to draw around it. It continues with more instructions, like how to wind a stem or wire a petal.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 74-75, general directions for making crepe and tissue paper flowers and pattern/instructions for making paper tulips.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 74-75, general directions for making crepe and tissue paper flowers and pattern/instructions for making paper tulips.

Instructions for a variety of flowers are included. A few examples are shown below with their patterns. This includes the poppy, poinsettia, violet, narcissus, and daisy. The directions for making daisies do not include a pattern. Instead, it mentions that Dennison sold ready-cut petals, as described earlier. They also sold kits for making particular flowers complete with all the necessary supplies such as petals, stamens, leaves, wire, and paper.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 82-83, instructions for making crepe and tissue paper flowers, including the poppy, poinsettia, violet, narcissus, and daisy.

Dennison Mfg. Co., Framingham, MA. Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914), pages 82-83, instructions for making crepe and tissue paper flowers, including the poppy, poinsettia, violet, narcissus, and daisy.

Art and Decoration in Dennison’s Crepe and Tissue Paper, 22nd Edition (1913, Reprinted 1914) by Dennison Mfg. Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

A Coffee Break with James Smithson

We’re looking forward to hosting Steven Turner, author of The Science of James Smithson, for our Annual Dibner Lecture on December 1st, 2021. Turner will explore a few lesser-known tales of Smithson’s work in a talk entitled “What Was James Smithson Doing in the Kitchen & Classroom?” Ahead of his lecture, Turner shares his recreation of Smithson’s coffee recipe.

In 1823, James Smithson wrote a short article about a novel method he’d developed for making coffee. The article, first published in the Thomson’s Annals of Philosophy, Vol. XXII, was reproduced in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections in 1881. Smithson maintained that this method had several advantages. It was economical, since it extracted all the flavor in the coffee beans, without letting any escape. And it didn’t require any special equipment so, he wrote, it would prove “of no small conveniency to travelers who have neither kettle, nor coffee-pot.” Finally, after the coffee was filtered it could be put back in a clean jar and kept warm in the boiling water. As long as it remained sealed, the coffee inside would not lose its flavor. It would remain hot and “ready at the very instant called for.”

First part of Smithson’s coffee recipe, “An Improved Method of Making Coffee”, as published in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (1881).

First part of Smithson’s coffee recipe, “An Improved Method of Making Coffee”, as published in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (1881).

Technically, this method of making coffee is an infusion, and it resembles the coffee produced with a modern French Press. However, in Smithson’s method the water is not quite so hot and it stays in contact with the coffee for much longer – so it extracts different compounds than other methods and the coffee tends to be milder and less bitter.

How to make “Smithson’s Coffee”

Ingredients:

- 1/4 to 1/3 cup roasted coffee beans

- About 2 cups of water

Method:

- Grind coffee beans in a mortar and pestle (medium to course grind). A coffee grinder also works.

- Combine coffee and water in a glass bottle and then seal with a cork. Leave the cork slightly loose.

- Place the bottle in a pan of water and bring to a boil. Tighten the cork once the water in the bottle gets hot.

- Leave the bottle in the boiling water for 6 to 8 minutes, or until the coffee looks done.

- Remove the bottle from the water, filter the coffee and enjoy.

Kitchen Essentials from Centuries Past

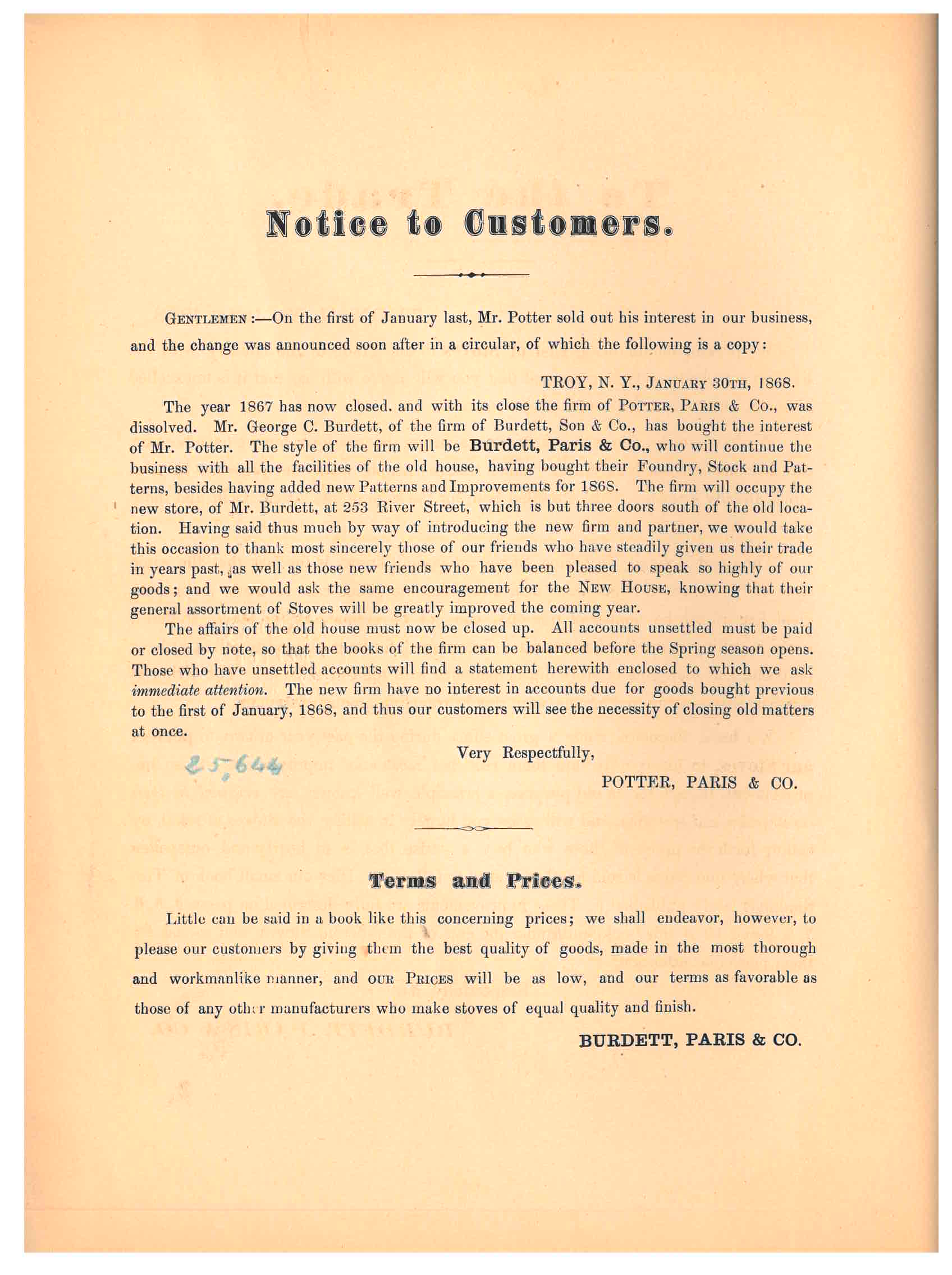

What comes to mind when you think of Thanksgiving? Family gatherings, time with friends, relaxing, traveling, or maybe a delicious meal? Those meals require work, and today we have the luxury of modern kitchen appliances. But imagine the time it took to prepare a meal in the 19th Century. This 1868 trade catalog gives us a small glimpse into possible kitchens of the past.

The trade catalog is titled Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868) by Burdett, Paris & Co. Their products were manufactured at the Troy Stove Works in Troy, New York. On the front cover, we discover a clue about the company’s history. It tells us that Burdett, Paris & Co. were successors to another company named Potter, Paris & Co.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), front cover.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), front cover.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [1], title page.As we turn the page, we learn more from a circular, or letter, dated January 30th, 1868. It was written by Potter, Paris & Co. The firm of Potter, Paris & Co. was dissolved at the end of 1867 at which time Mr. George C. Burdett of Burdett, Son & Co. bought “the interest of Mr. Potter.” The new company became known as Burdett, Paris & Co. and planned to continue the business “with all the facilities of the old house, having bought their Foundry, Stock and Patterns.”

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [1], title page.As we turn the page, we learn more from a circular, or letter, dated January 30th, 1868. It was written by Potter, Paris & Co. The firm of Potter, Paris & Co. was dissolved at the end of 1867 at which time Mr. George C. Burdett of Burdett, Son & Co. bought “the interest of Mr. Potter.” The new company became known as Burdett, Paris & Co. and planned to continue the business “with all the facilities of the old house, having bought their Foundry, Stock and Patterns.”

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [2], Notice to Customers with circular written by Potter, Paris & Co. and Terms and Prices written by Burdett, Paris & Co.The letter continues by explaining that the new store would be located at 253 River Street, just a few doors away from where Potter, Paris & Co. had been located. Products were manufactured at Troy Stove Works. An image of the works is shown on the back cover of this catalog. According to that page, the foundry had been erected just a few years earlier, in the fall of 1865.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [2], Notice to Customers with circular written by Potter, Paris & Co. and Terms and Prices written by Burdett, Paris & Co.The letter continues by explaining that the new store would be located at 253 River Street, just a few doors away from where Potter, Paris & Co. had been located. Products were manufactured at Troy Stove Works. An image of the works is shown on the back cover of this catalog. According to that page, the foundry had been erected just a few years earlier, in the fall of 1865.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), back cover, Troy Stove Works.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), back cover, Troy Stove Works.

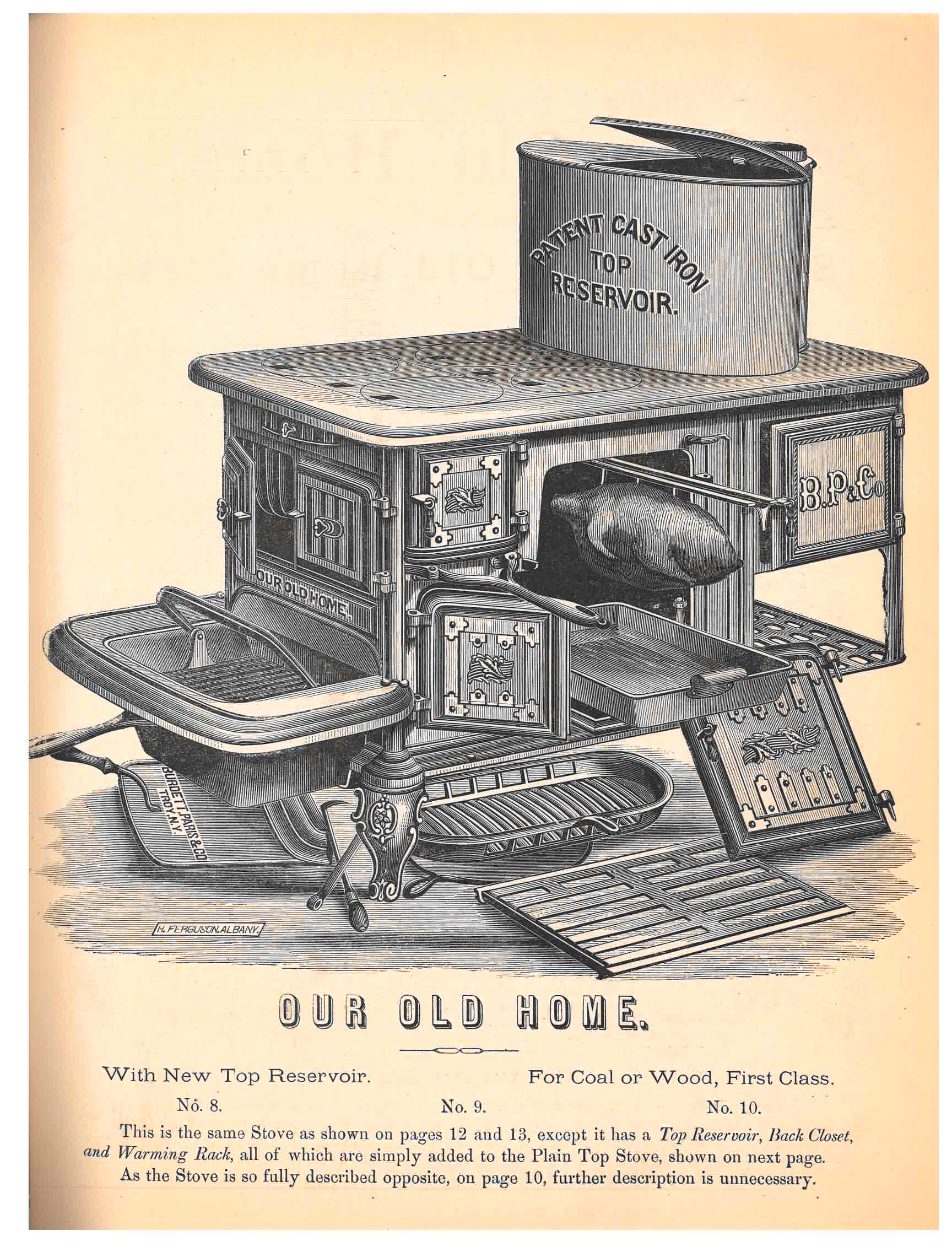

Now, having learned a little about the company, let’s explore some of their stoves. One stove was called “Our Old Home.” Its fuel was coal or wood. It included a quite convenient feature. The roasting arrangement, shown below, made it easier for the cook to baste. Meat was suspended from a movable self-supporting rack which could be pulled out. A dripping pan, attached to a movable crane, was positioned below the rack and could also be pulled out. This allowed the cook to baste meat when it was outside of the oven. The meat could also be placed on or removed from the rack when outside of the oven.

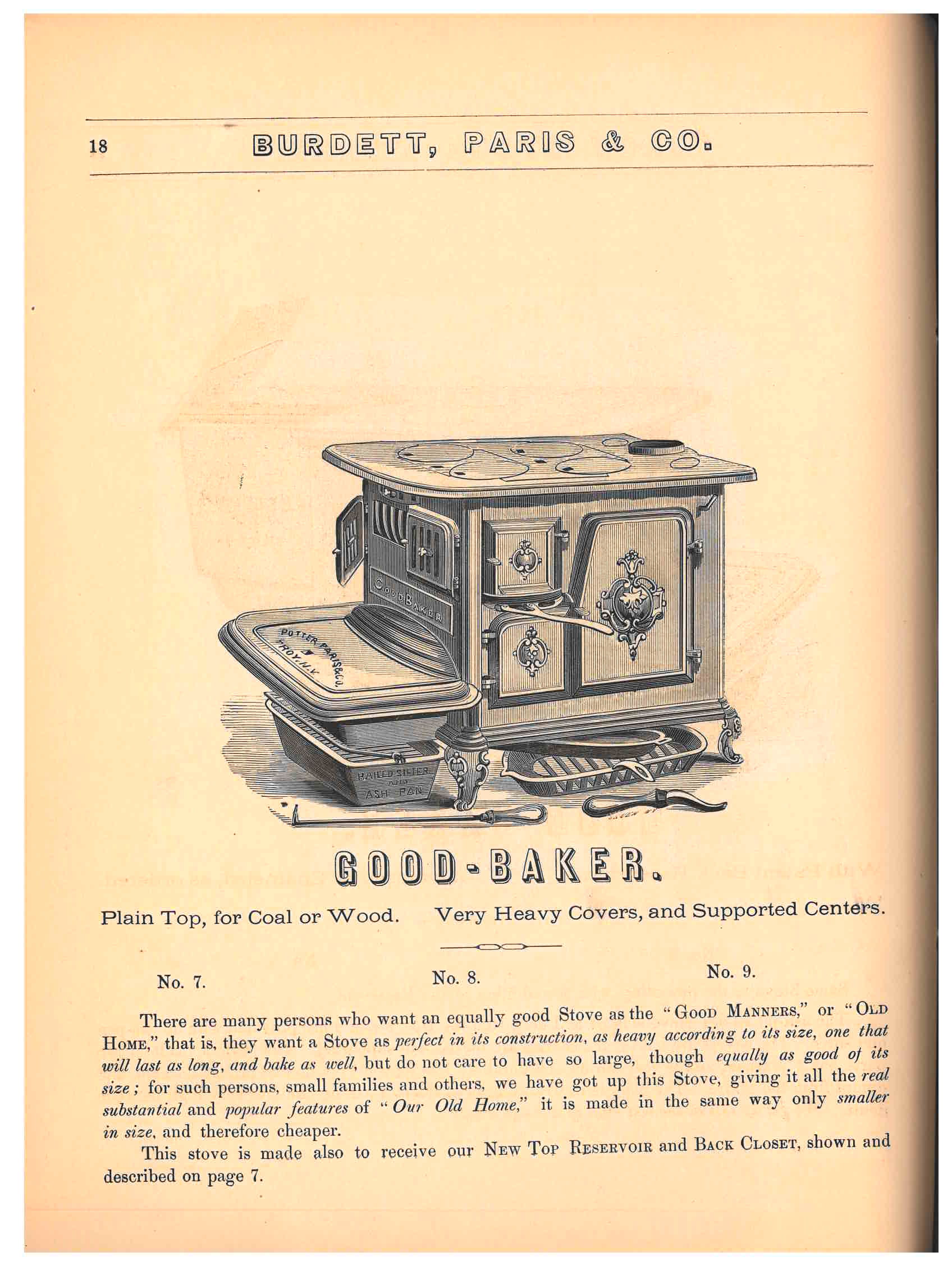

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [11], “Our Old Home” stove showing meat using the roasting arrangement.Another stove is named the “Good-Baker.” Shown below, it included “all the real substantial and popular features of ‘Our Old Home’” but was smaller in size and less expensive. The “Good-Baker” used coal or wood for fuel.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), unnumbered page [11], “Our Old Home” stove showing meat using the roasting arrangement.Another stove is named the “Good-Baker.” Shown below, it included “all the real substantial and popular features of ‘Our Old Home’” but was smaller in size and less expensive. The “Good-Baker” used coal or wood for fuel.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 18, “Good-Baker” stove.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 18, “Good-Baker” stove.

Flipping a few pages further along, we come across a stove called the “Golden-West.” The catalog explains that it was made “for the Soft Coal of the Western States.” It was identical in size to “Our Old Home” and, as described in the catalog, “made with only a little less care and finish.” Its fuel was either soft coal, as already mentioned, or wood.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 24, “Golden-West” stove.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 24, “Golden-West” stove.

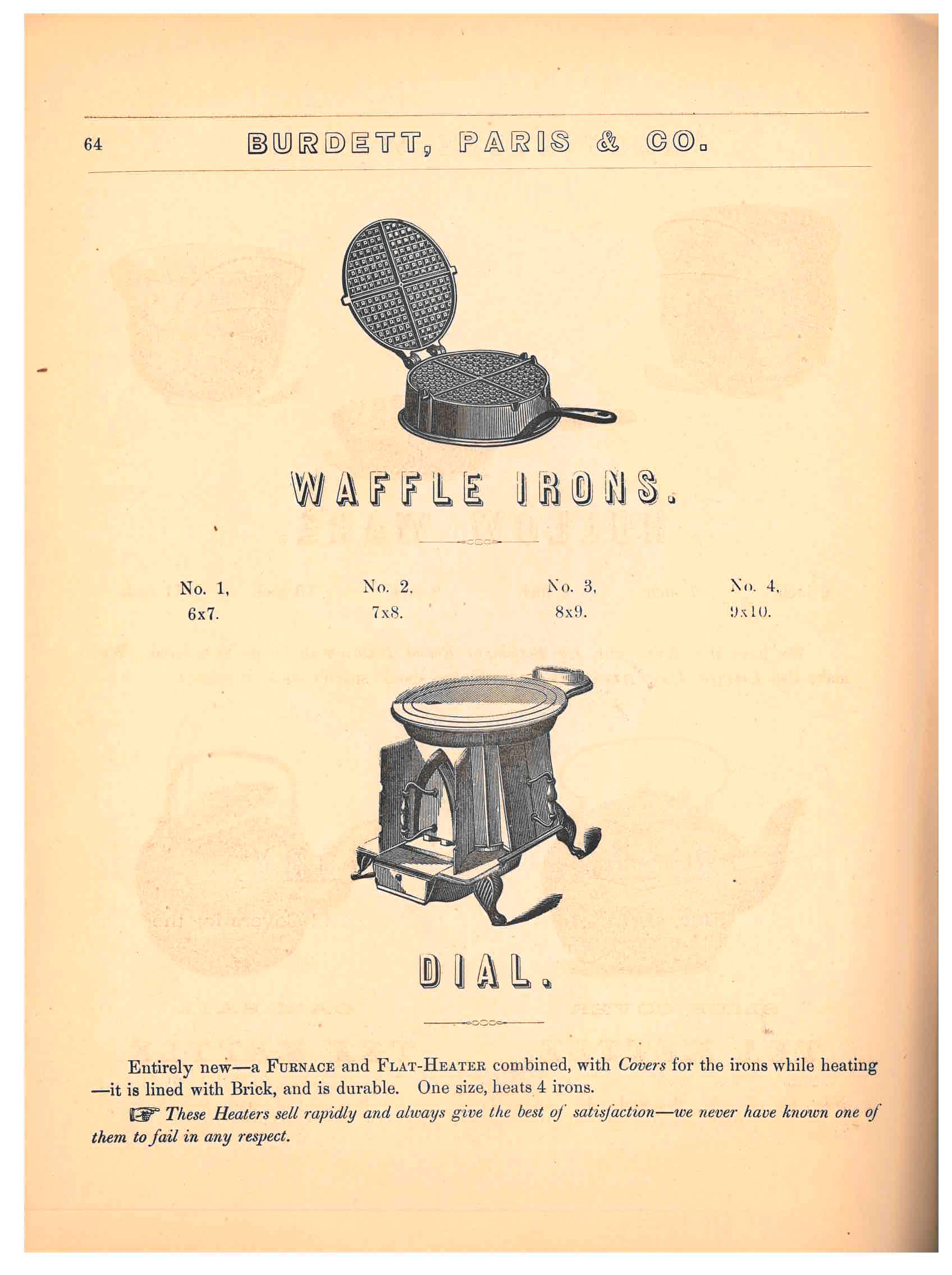

Burdett, Paris & Co. also manufactured other items such as hollow ware, tea kettles, and, as shown below, waffle irons. Another product shown below was the Dial. Described as “entirely new,” it was a combination furnace and flat-heater with covers for heating irons. It was capable of heating four irons.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 64, Waffle Irons and Dial.

Burdett, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868), page 64, Waffle Irons and Dial.

As mentioned earlier, Burdett, Paris & Co. were successors to the firm of Potter, Paris & Co. The National Museum of American History Library also holds a trade catalog by Potter, Paris & Co. It is titled Catalogue of Stoves (1866), and as noted below on its front cover, it covered the years of 1866-1867.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), front cover.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), front cover.

Both trade catalogs, Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868) by Burdett, Paris & Co. and Catalogue of Stoves (1866) by Potter, Paris & Co., are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Upcoming Event: What Was James Smithson Doing in the Kitchen & Classroom?

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives invites you to join us for our 2021 Dibner Library Lecture, featuring Steven Turner, “What Was James Smithson Doing in the Kitchen & Classroom?”

Wednesday, December 1st at 5 pm ET

Register Now

James Smithson was an 18th century English chemist, geologist, and mineralogist – and also the founder of the Smithsonian Institution. Most of what we know about Smithson’s science comes from his twenty-six published articles, which Steven Turner studied in his recent book, The Science of James Smithson (Smithsonian Books, 2020). Turner argues persuasively that Smithson was much more accomplished than previously thought. And he shows that Smithson made important contributions to a wide range of scientific fields, including: chemistry, mineralogy, geology, botany, electricity, and even meteorology.

One of the surprises of Turner’s study was the extent to which Smithson’s scientific writings also offer clues about his personal interests and beliefs. In this year’s Dibner Library Lecture, Turner will dig deeper into some of the lesser-known tales of Smithson’s work, like how Smithson’s interest in cooking helped him solve a scientific puzzle. He’ll also discuss the unexpected story of Smithson’s interest in scientific education – a lifelong interest that may have led to the founding of the Smithsonian.

About the Speaker:

Steven Turner is a historian of science and for 32 years was curator of Physical Sciences at the Smithsonian Institution. His research interests include the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the uses of scientific instruments. For many years he edited the science history journal Rittenhouse, and he contributed to numerous exhibits and web projects. Towards the end of his career, he became interested in the English chemist, James Smithson, the founder of the Smithsonian Institution. Because Smithson’s scientific writings are famously difficult to follow, in addition to conventional historical research, Turner made extensive use of replications of Smithson’s experiments, many of them with the same tools and natural materials that Smithson would have used – which sometimes yielded surprising insights. Turner’s book, The Science of James Smithson, was published in the fall of 2020.

Registration

Register for this program via Zoom. You’ll also get an opportunity to opt in to receive emails from us, including invitations to future programs.

We are committed to providing access services so all participants can fully engage in these events. Optional real-time captioning will be provided. If you need other access services, please email SLA-RSVP@si.edu. Advanced notice is appreciated.

This program will be recorded and made available following the event. You will find it on the event page and on our YouTube channel.

This program is part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ commemoration of the 175th anniversary of the Institution’s founding.

Some Archival Career Advice

In honor of American Archives Month, we’re highlighting career tips from archivist Jennifer Wright. Jennifer leads the Archives and Information Management Team within our Smithsonian Institution Archives.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives receives dozens of inquiries every year from students and recent graduates about the archives profession and how to become an archivist. Since this is such a popular topic, we decided to make our responses to the most common questions available to a wider audience. While the responses below are intended to address the archival profession in general, they ultimately reflect my own experiences and those of my immediate colleagues.

Records storage at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Records storage at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

What does an archivist do?

Archivists perform a wide variety of tasks. In a smaller archives, a few individuals may do everything while, in a larger archives, archivists may specialize in specific aspects of the work. Traditionally, an archivist works with donors or the staff of its parent institution to acquire new collections; organizes and rehouses collections (also known as processing); describes collections and writes finding aids; and assists researchers in using the collections. Some archivists specialize in the acquisition, management, description, and preservation of born-digital files, web-based content, photographic materials, or audiovisual recordings. Other aspects of the job may include records management, digitization, metadata creation, public outreach, research, writing, or teaching.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I enjoy learning about a wide variety of topics within the collections I process. I also enjoy going behind the scenes and exploring our museums and research centers from the inside out.

What qualities are employers looking for in an archivist?

Many employers will be looking for applicants who can work both independently and on a team; demonstrate strong research and writing skills; exhibit attention to detail; are creative problem solvers; and show a natural curiosity. Many positions will require data management, digitization, and digital preservation in addition to working with digital files for the purposes of appraisal and reference. A solid background in basic technical skills will be essential. Some employers may also be looking for knowledge of a particular topic related to their collection, such as local history or aviation. Intern, volunteer, or other hands-on experience will often be a critical factor in deciding which applicant to hire. The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives offers several internship programs each year, as do other archival repositories around the Institution.

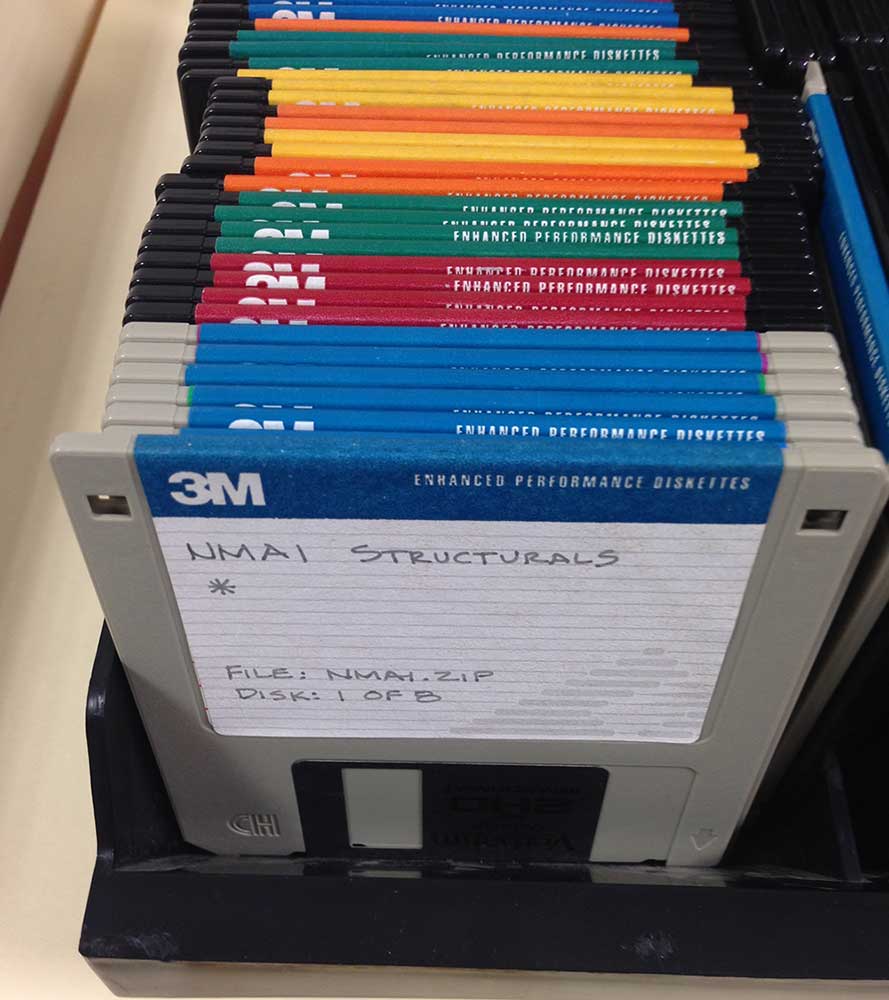

Diskettes from the Smithsonian’s Office of Facilities Engineering and Operations.

Diskettes from the Smithsonian’s Office of Facilities Engineering and Operations.

What degree do you need to be an archivist?

Many, but not all, employers will require a Master of Library Science, a Master of Library and Information Science, “or equivalent.” A Master of Library Science was once a common degree for new archivists, but as traditional library school programs have evolved, many universities have renamed the degree (often combining the terms “library” and “information”) or have created a separate degree for the archives, records, and information management (sometimes called a Master of Information Studies). A very limited number of universities have even created a degree specifically for archival studies. Employers generally recognize that these degrees tend to be similar. When deciding on a graduate school, look at the courses that are included in the curriculum, not just the title of the degree offered. Other common graduate degrees held by archivists include public history and museum studies. Some positions may only require an undergraduate degree, but a graduate degree will likely be “preferred.”

The Smithsonian Institution Archives’ Collections Vault of Historic Photography with John Dillaber, Staff Digital Imaging Specialist, by Ken Rahaim.

The Smithsonian Institution Archives’ Collections Vault of Historic Photography with John Dillaber, Staff Digital Imaging Specialist, by Ken Rahaim.

What other subjects are helpful in your job?

The research and writing skills gained through history, English, and other liberal arts classes are helpful. A second language can also be useful in a setting where non-English documents are found in collections. Archival collections can deal with any topic though, so there is no way to tell which subjects may be useful later. Some employers may require archivists to have a background in a specific subject matter while others will be looking at professional skills first and assume the subject matter will be learned on the job. Furthermore, workshops or introductory courses in information technology skills such as database design, programming, or data forensics could be assets in many different settings.

What recommendations do you have for a future archivist?

Whether you are just beginning your archival training or will be looking for a job soon, periodically check the job listings. Take note of the requirements and preferred qualifications for positions that interest you. More than any advice, these listings will give you a good idea of what skills and knowledge you need to acquire in order to reach your ultimate goals. Also, do not limit yourself to a specialty. Taking specialized courses will make you competitive for certain types of jobs, but be sure to take fundamental courses in all aspects of archival work to meet the minimum requirements for the largest number of jobs. In addition, whenever possible, take courses from adjunct professors who also work in an archives. From these professors, you will often learn how to make decisions about priorities in settings where budget and staff are limited.

Be sure to take advantage of the numerous online resources available to new and future archivists, many of which are free to access. Professional organizations such as the Society of American Archivists, ARMA International (for records management, information management, and information governance), the National Association of Government Archives and Records Administrators (NAGARA), the Association for Information and Image Management (AIIM), and the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) are all great places to begin.

Tracing Anthropologist Zelia Nuttall Through Smithsonian Collections

Anthropologist Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall was an expert in Mesoamerican people and artifacts. A remarkable Mexican American scholar, she helped change the conversation around pre-Columbian cultures. Many of her publications are held in the collections of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and traces of her work can be found in repositories around the Institution.

Nuttall was born in San Francisco in 1857 to a family with both wealth and deep Mexican ties. Her father, Robert Nuttall, was an Irish physician. Her mother, Maria Magdalena Parrott, was born in Mexico, the daughter of a diplomat banker. It is said that Zelia first became intrigued with Mesoamerican civilizations when her mother gifted her a copy of The Antiquities of Mexico, a beautiful facsimile of ancient codices compiled by Lord Gainsborough. Though her family eventually left California for Europe, Nuttall’s natural curiosity was complemented by a solid education by private tutors, and she was fluent in both Spanish and German.

Portrait of Zelia Nuttall holding a fan. Courtesy University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Portrait of Zelia Nuttall holding a fan. Courtesy University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

Nuttall took her second trip to Mexico in 1884, accompanied by family. She collected small terra cotta heads near Teotihuacan, which would become the subjects of her first article, published in The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts in 1886. Contemporary anthropologists had not given them much attention, considering them puzzling novelties. But Nuttall marveled at the diversity of them, praised their craftsmanship, and attempted to classify and explain them.

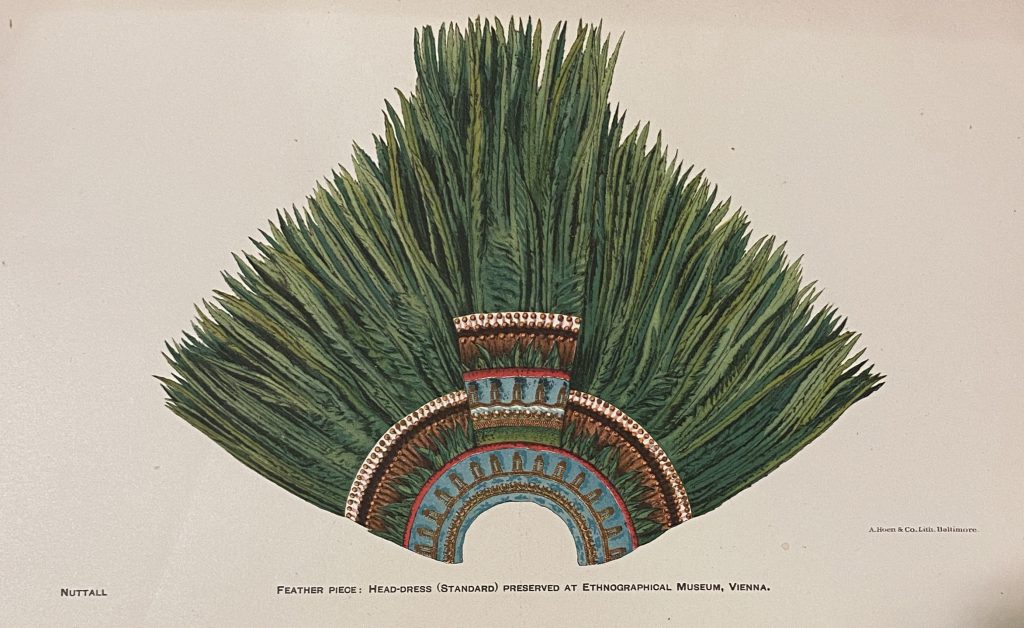

Shortly after, she became acquainted with Frederick Ward Putnam of the Peabody Museum of Harvard and was offered the role of Special Assistant in Mexican Archeology. She published several articles and books towards the end of the 19th century, including Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895) (available online via the Library of Congress). In 1901, she published a lengthy comparison of cultures and religions in The fundamental principles of Old and New World Civilizations (available online via Brigham Young University). The book, supported by Putnam, suggested that since many cultures around the world shared similarities, perhaps ancient European and Asian civilizations interacted with ancient Americans. Though later discredited, the concept did help adjust perceptions of Mesoamerican cultures, often considered unrefined, and place them on the same level as the Egyptians and Greeks.

“Feather Piece: Head-Dress (Standard) Preserved at Ethnographical Museum, Vienna”, Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895).

“Feather Piece: Head-Dress (Standard) Preserved at Ethnographical Museum, Vienna”, Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895).

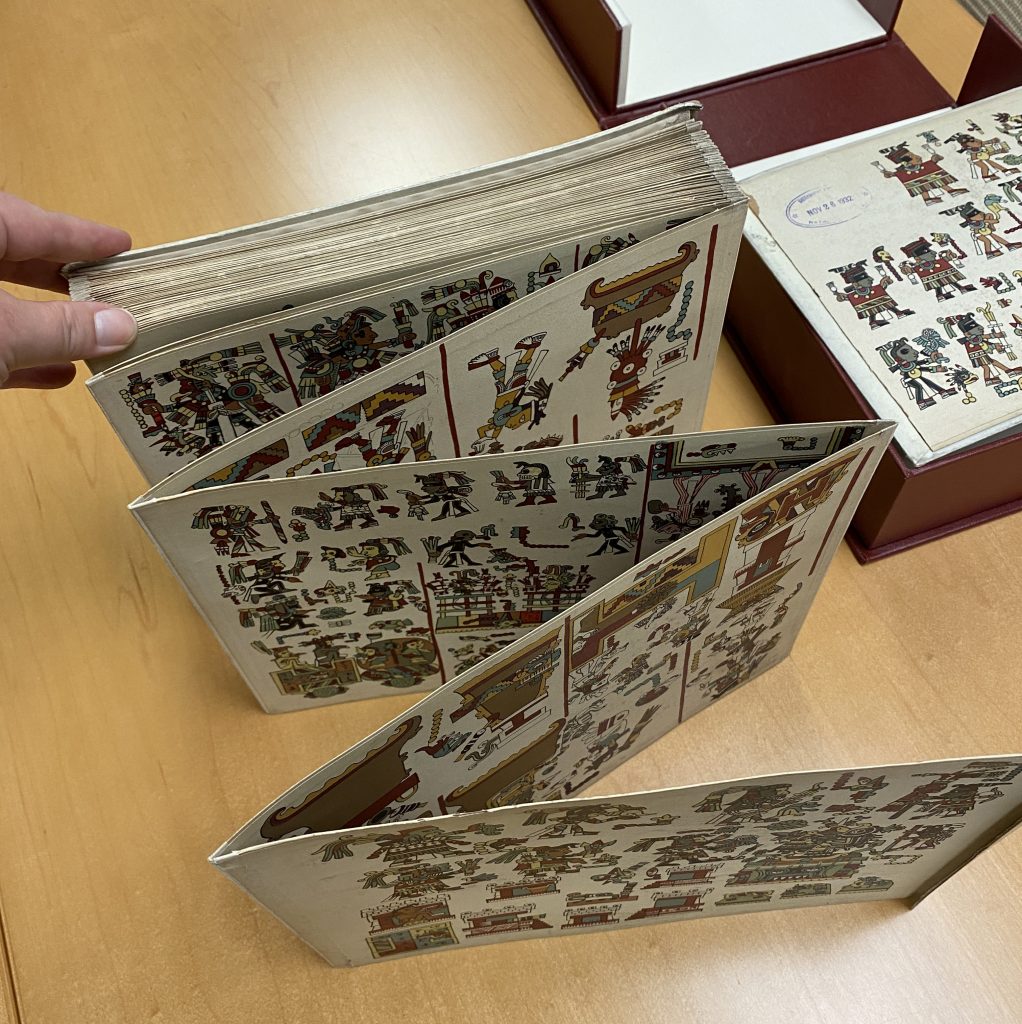

One of Nuttall’s most notable works is her namesake Codex Nuttall, a translation and facsimile of a 13th century Mixtec folding screen book. Nuttall traveled to England to research the original, then owned Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche and now in the collections of the British Museum. The codex had previously been dismissed, thought to be a children’s book or one of little consequence, but Nuttall found it to be the “most superb example of an Ancient Mexican historical manuscript” she had ever seen. Nuttall translated the codex, realizing that one side tells the history of important Mixtec centers and the other side recording the genealogy, marriages, and political accomplishments of the ruler Eight Deer Jaguar Claw.

Seeing the presentation copy of the Codex Nuttall in our John Wesley Powell Library of Anthropology you can’t help but admire Nuttall’s attention to detail in her reproduction. In the facsimile, Nuttall recreates the experience of the original folded manuscript. Though the original was no longer protected by sturdy end pieces, she suspected they had been at one time and designed parchment covers for her version in “strict accordance with native methods”.

Codex Nuttall (1902), opened to show folding screen shape.

Codex Nuttall (1902), opened to show folding screen shape.

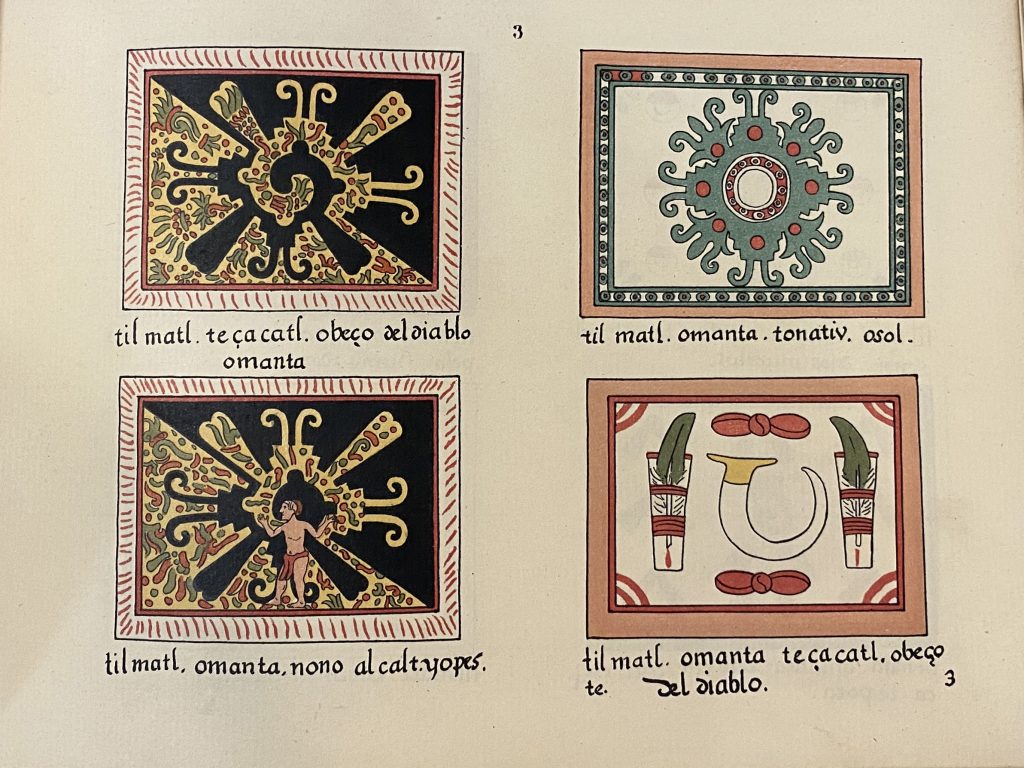

In 1903, Nuttall published another facsimile and translation, this time of the “Magliabecchi manuscript” in The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (see the University of Virginia’s copy online). The source manuscript, once owned by Antonio Magliabecchi, was created sometime during the 16th century, likely by Indigenous scribes at the behest of Spanish clergy, to recreate an even earlier codex. Nuttall first encountered it in 1890 at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze in Florence while searching for Mesoamerican works in European libraries. According to her preface, transcribing and researching the manuscript led Nuttall to important discoveries of the Ancient Mexican Calendar System which “changed the current views held on the subject”.

Page 3, The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (1903).

Page 3, The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (1903).

Though archaeology was often a part of Nuttall’s work, it wasn’t until 1910 that she endeavored to lead an official dig. She had researched the history of La Isla de Sacrificios, a small island near Veracruz, where Bernal Diaz had reportedly witnessed ceremonial sacrifices in the 1500s. Nuttall made a quick visit, during which she unearthed pottery and the partial walls of a structure. She reported her findings to the Mexican government and requested permission to return for a more comprehensive excavation but was stymied by Leopoldo Batres, the Inspector of Monuments. Weeks later Bartres visited La Isla de Sacrifios himself and claimed the discovery as his own. Nuttall detailed her experience in American Anthropologist and Batres issued a pretty scathing (and a bit sexist) rebuttal. In La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910), available in our Digital Library, Batres disputes her claims and suggests Nuttall suffered from “el histerismo femenino” (female hysteria).

Cover, La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910).

Cover, La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910).

Nuttall was part of an extensive network of anthropologists, archaeologists, and other scientists throughout her career. She was a member of the Archeological Institute of America, the American Philosophical Society and among the first women to represent the United States in the International Congress of Americanists. Nuttall’s correspondence with colleagues and other papers are held by several archival repositories at the Smithsonian. The National Anthropological Archives holds manuscript materials related to the Codex Nuttall and other aspects of Nuttall’s work. Nuttall’s letters to George Hubbard Pepper, an anthropologist with the Bureau of American Ethnology and the National Museum of the American Indian, are held by National Museum of the American Indian. The Archives of American Gardens has photos of Nuttall’s gardens at her home in Mexico, Casa Alvarado. Our own Smithsonian Institution Archives includes letters from Nuttall to curator George Brown Goode following up on the possible publication of her aforementioned article on Ancient Mexican feather work.

Casa Alvarado: Garden Club of America members at lunch in the garden of this former home of scholar Zelia Nuttall. Lantern slide by Edward Van Altena. Courtesy Archives of American Gardens, Smithsonian Gardens.

Casa Alvarado: Garden Club of America members at lunch in the garden of this former home of scholar Zelia Nuttall. Lantern slide by Edward Van Altena. Courtesy Archives of American Gardens, Smithsonian Gardens.

Items collected by Nuttall have also found a home at the Smithsonian. The National Museum of Natural History’s Botany collections include samples of Chenopodium berlandieri or lamb’s quarters, collected near Mexico City. The National Museum of the American Indian holds Mixtec artifacts collected by Nuttall, including skirts, sashes, and beads.

Nuttall died in 1933, with a number of professional titles, accomplishments, and historical discoveries to her name. The bibliography in her obituary in American Anthropologist lists over 70 publications. Through her work, she examined and explained Mesoamerican civilization and uncovered Indigenous art, technology, and culture previously lost to colonial forces.

Further Reading from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives:

Batres, Leopoldo. La Isla de Sacrificios, la Señora Zelia Nuttall de Pinard y Leopoldo Batres (1910).

Chiñas, Beverly Newbold. “Zelia Maria Magdalena Nuttall”, Women anthropologists: a biographical dictionary (1988).

Gainsborough, Edward. The Antiquities of Mexico (1831-1848).

Nuttall, Zelia. Ancient Mexican feather work at the Columbian historical exposition at Madrid (1895).

Nuttall, Zelia. The book of the life of the Ancient Mexicans (1903).

Nuttall, Zelia. Codex Nuttall (1902).

Nuttall, Zelia. The fundamental principles of Old and New World Civilizations (1901).

Other Resources:

McNeill, Leila. “The Archaeologist Who Helped Mexico Find Glory in Its Indigenous Past”, Smithsonian.com (November 5, 2018).

Nuttall, Zelia. “The Terracotta Heads of Teotihuacan”. The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1886), pp. 157-178.

Nuttall, Zelia. “The Island of Sacrificios”, American Anthropologist, 12 (1910): 257-295.

Tozzer, Alfred M. “Zelia Nuttall”. American Anthropologist, 35 (1933): 475-482.

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles: Fall 2021 Edition

Ready to fall into another round of digital jigsaw puzzles? We’ve put together, or rather, taken apart five new puzzles based on images in our collections.

Play them right here on our blog or use the links to play full screen. Each puzzle is set at about 100 pieces but they are customizable to any skill set. Click the grid icon in the center to adjust the number of pieces. All of the images are available in our Digital Library, Image Gallery, Biodiversity Heritage Library or Smithsonian Institution Archives Collections. Feel free to explore and make your own!

Miss our previous puzzles? Find them here.

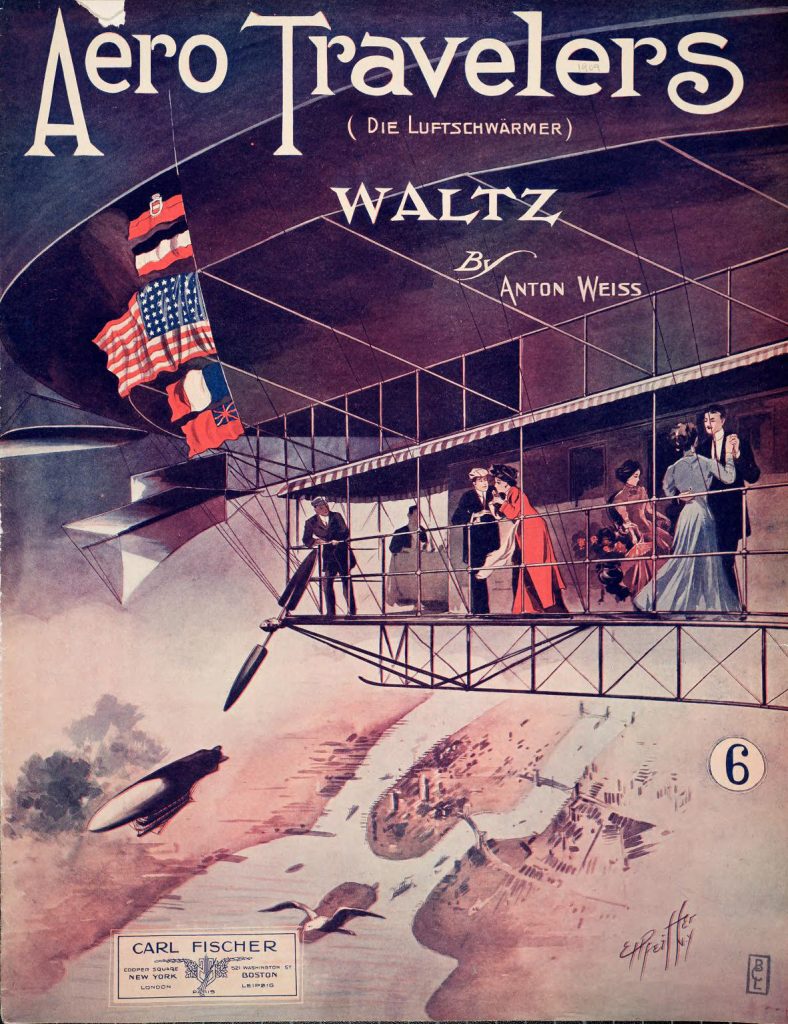

Cover, Aero Travelers (1909).

Aero Travelers is one of hundreds of pieces of aeronautical-themed sheet music collected by Bella C. Landauer (1874–1960). Landauer took an interest in aviation when her son became a pilot and scoured music shops to amass her collection. Landauer is featured with other notable enthusiasts who helped us build our collections in our current exhibition, Magnificent Obsessions: Why We Collect.

Play online: https://jigex.com/jLM64

Cover, Aero Travelers (1909).

Cover, Aero Travelers (1909).

Jigsaw Puzzle

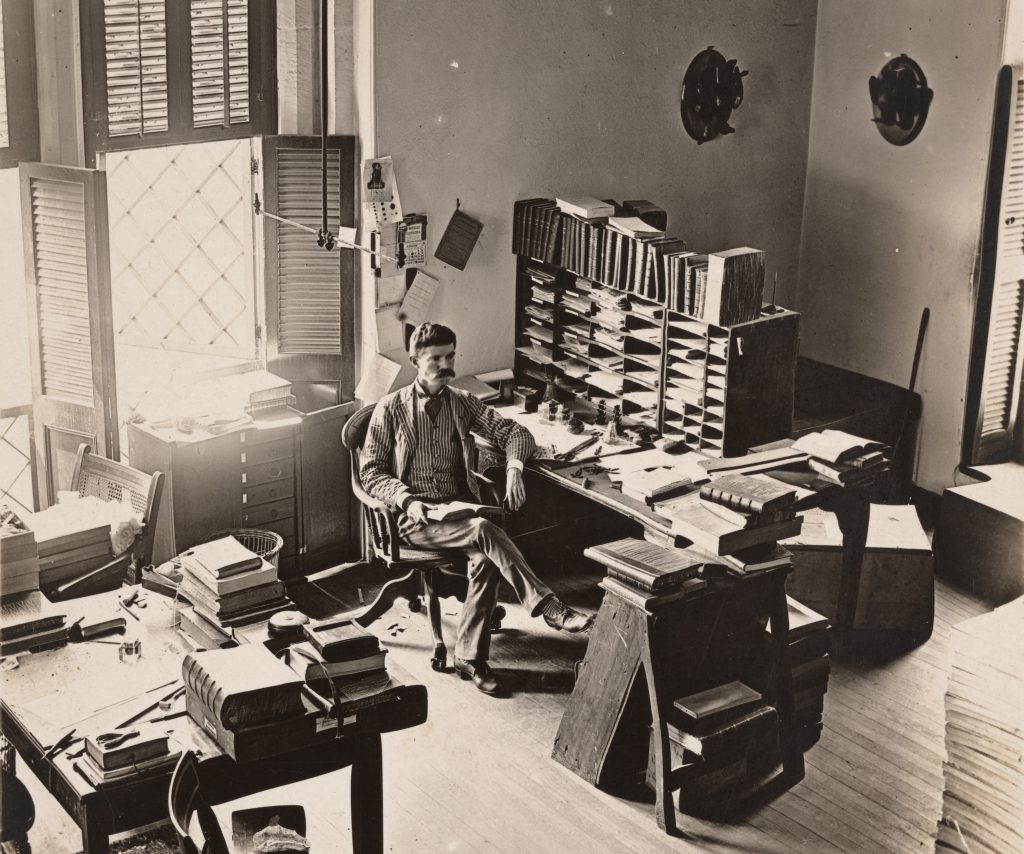

Portrait of Robert Ridgway (1850-1929) in His Office, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image No. SIA_000095_B27E_010, detail.

Robert Ridgway was a bird expert mentored by Smithsonian Secretary Spencer Fullerton Baird. In 1874, Ridgway was appointed ornithologist on the staff of the United States National Museum. He was appointed Curator of the Department of Ornithology in 1880. This photo gives us a peek inside Ridgway’s book-filled office in the South Tower of the Smithsonian Institution Building, or Castle. Ridgway himself was a prolific author and illustrator of bird books and developed several guides to help fellow natural history writers accurately depict color.

Play online: https://jigex.com/LdUNG

Portrait of Robert Ridgway (1850-1929) in His Office, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image No. SIA_000095_B27E_010, detail.

Portrait of Robert Ridgway (1850-1929) in His Office, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image No. SIA_000095_B27E_010, detail.

Jigsaw Puzzle

Tafel XXVII, Die Nordamerikanische Vogelwelt (1891).

Speaking of Ridgway, our next piece of puzzle art is courtesy of the ornithologist himself. This illustration of Spiza americana, or the dickcissel, was drawn by Ridgway and featured in the book Die Nordamerikanische Vogelwelt. Written by Henry Nehrling, it was a guide to American birds published in German in 1891. The dickcissel is a small, sparrow-sized bird found in grasslands and prairies.

Play online:https://jigex.com/aoRGQ

Tafel XXVII, Die Nordamerikanische Vogelwelt (1891).

Tafel XXVII, Die Nordamerikanische Vogelwelt (1891).

Jigsaw Puzzle

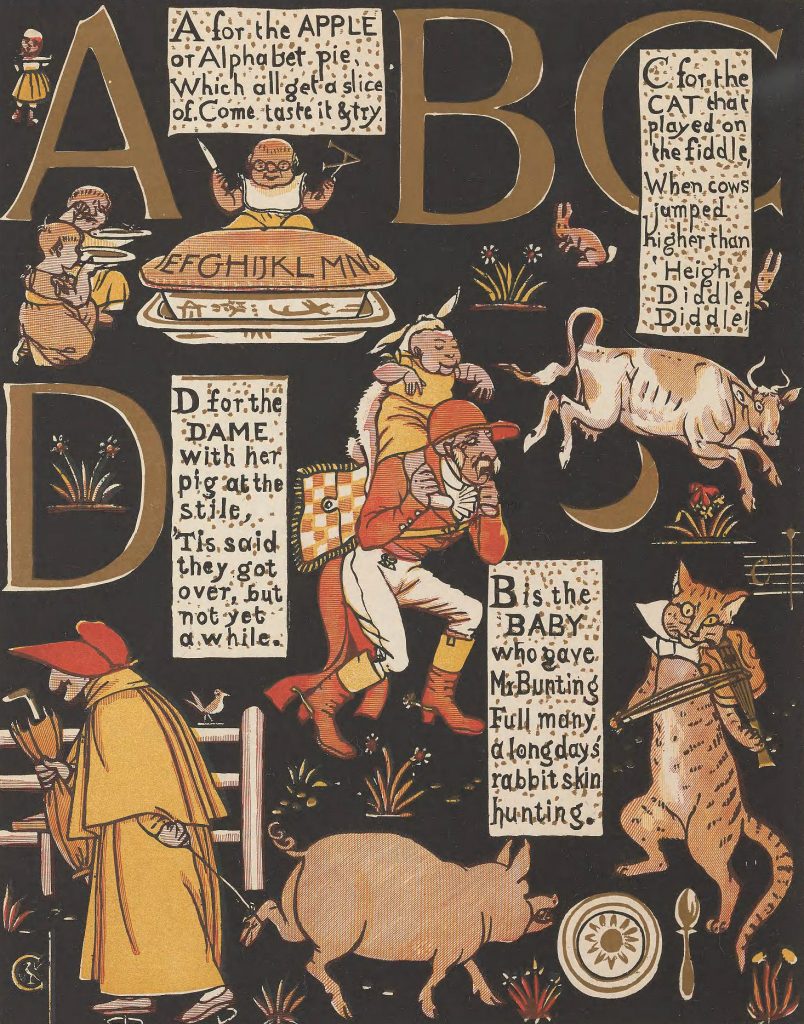

First page, The absurd A.B.C (1874).

Generations of young people have been captivated by Walter Crane. Crane was one of the most influential book illustrators of the 19th century, creating iconic versions of “Beauty and the Beast”, “The Frog Prince”, “The Sleeping Beauty” and more. This illustration from the first page of The absurd A.B.C. borrows bits from several well-known nursery rhymes. Find more of Crane’s work in our Digital Library.

Play online:https://jigex.com/EcCnw

First page, The absurd A.B.C (1874).

First page, The absurd A.B.C (1874).

Jigsaw Puzzle

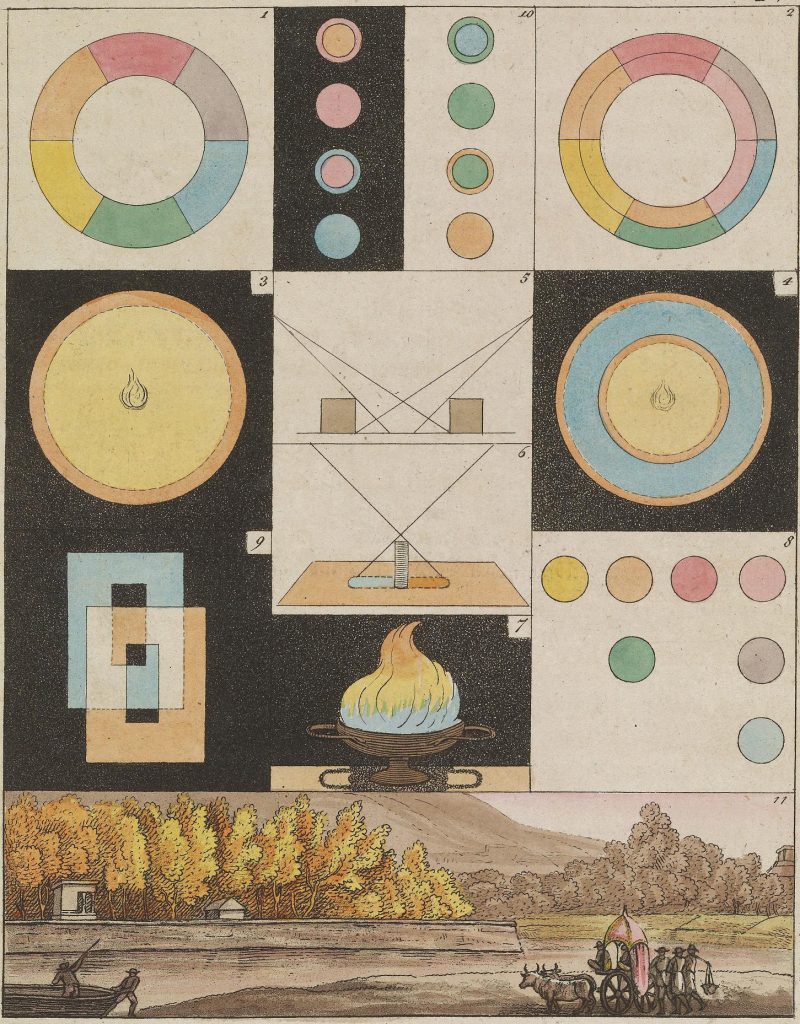

Plate I, Zur Farbenlehre (1810).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe challenged Isaac Newton’s views on color, arguing that color was not simply a scientific measurement, but a subjective experience perceived differently by each viewer. His contribution was the first systematic study on the physiological effects of color. Goethe’s views were widely adopted by artists. Although Goethe is best known for his poetry and prose, he considered Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors) his most important work. Learn more about the science of color in our online exhibition, Color in a New Light.

Play online:https://jigex.com/zdXRE

Plate I, Zur Farbenlehre (1810).

Plate I, Zur Farbenlehre (1810).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Early 20th Century Chocolate and the Machines That Made It

October might bring to mind costumes, pumpkins, treats, and candy. But have you ever wondered how all that chocolate is made? What types of machines are used? Let’s travel back to the early 20th Century to learn more about some of those chocolate-making machines.

This trade catalog is titled Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915) by Samuel Carey. It includes machines for various steps in the chocolate-making process, such as roasters, melangeurs, mixers, refiners, coating machines, and more.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), front cover.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), front cover.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), title page.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), title page.

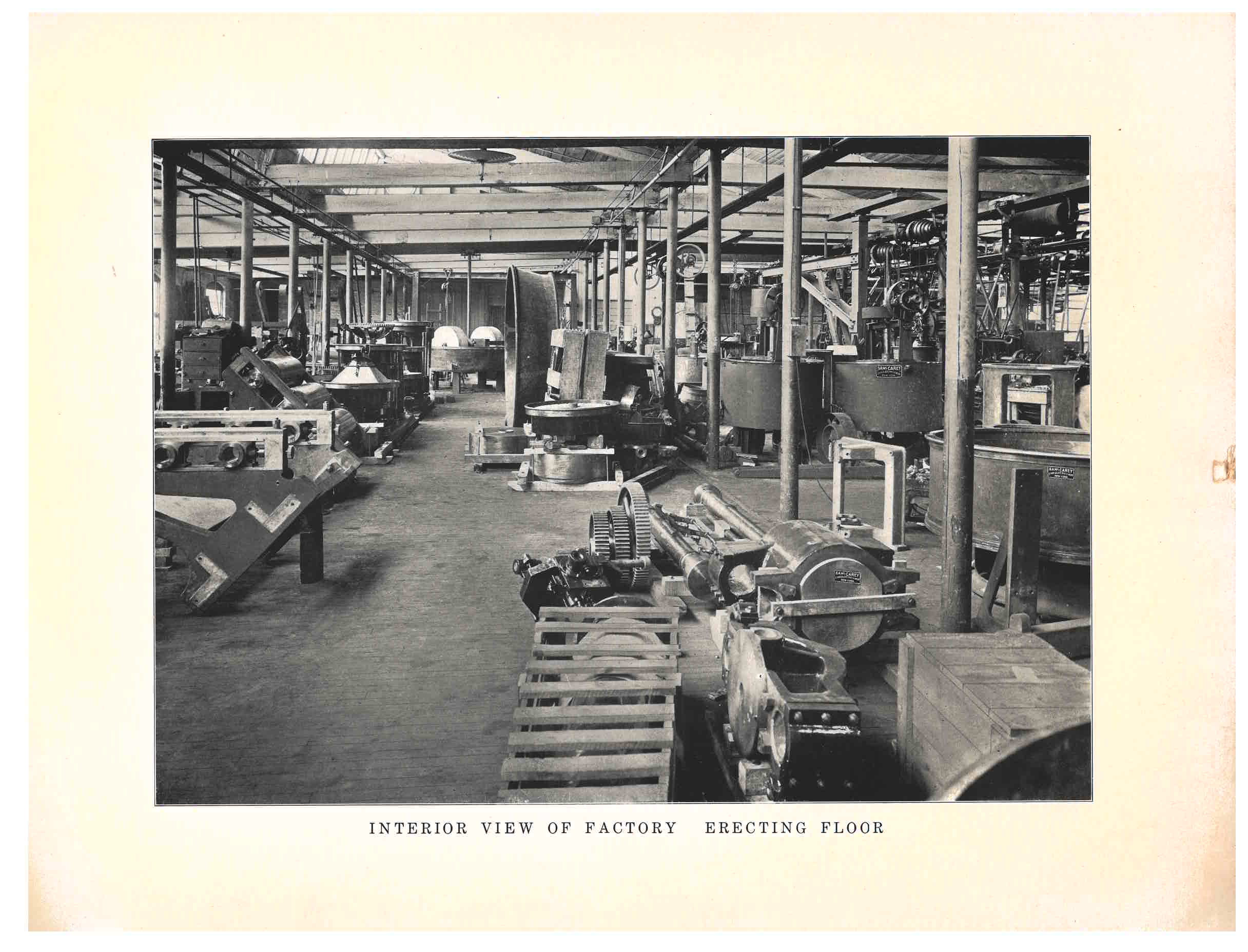

At the time this catalog was printed, the factory for Samuel Carey was located in Glendale, Brooklyn, New York while their office was located in New York City. This particular catalog includes an exterior image of the factory in Glendale and an interior image of the factory’s erecting floor, both shown below. Let’s flip through this catalog to learn a bit about a few of the machines built at this factory.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), unnumbered page [3], exterior view of Glendale Factory.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), unnumbered page [3], exterior view of Glendale Factory. Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), unnumbered page [5], interior view of factory’s erecting floor.One machine was the Cocoa Bean Roaster. According to this catalog, there were several ideas in regard to roasting cocoa beans. It explains that some at that time felt slow roasting was best “to maintain the flavor of the cocoa” while others preferred rapid roasting. There were also preferences on whether steam should be allowed to escape or not during the roasting process. Samuel Carey built roasters that were capable of both rapid or slow roasting and the ability to control the escape of steam for either moist or dry roasting.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), unnumbered page [5], interior view of factory’s erecting floor.One machine was the Cocoa Bean Roaster. According to this catalog, there were several ideas in regard to roasting cocoa beans. It explains that some at that time felt slow roasting was best “to maintain the flavor of the cocoa” while others preferred rapid roasting. There were also preferences on whether steam should be allowed to escape or not during the roasting process. Samuel Carey built roasters that were capable of both rapid or slow roasting and the ability to control the escape of steam for either moist or dry roasting.

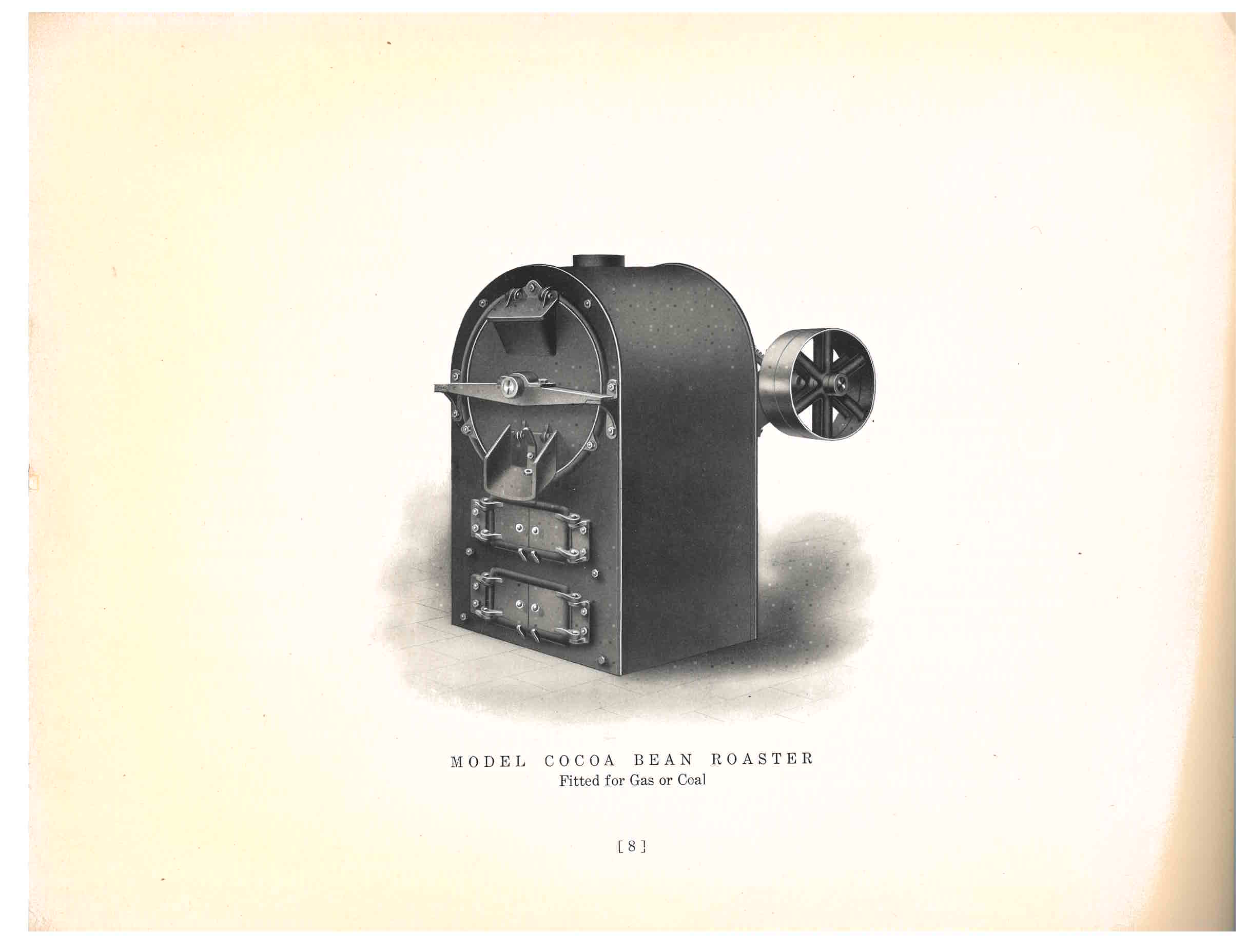

The Model Cocoa Bean Roaster which produced a moderate output is shown below. Due to the arrangement of the agitators within the drum of this machine, the batch was “constantly and thoroughly mixed.” This, as explained in the catalog, produced a uniform roast of the cocoa beans. It was also possible to test the beans at any time during the process.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 8, Model Cocoa Bean Roaster.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 8, Model Cocoa Bean Roaster.

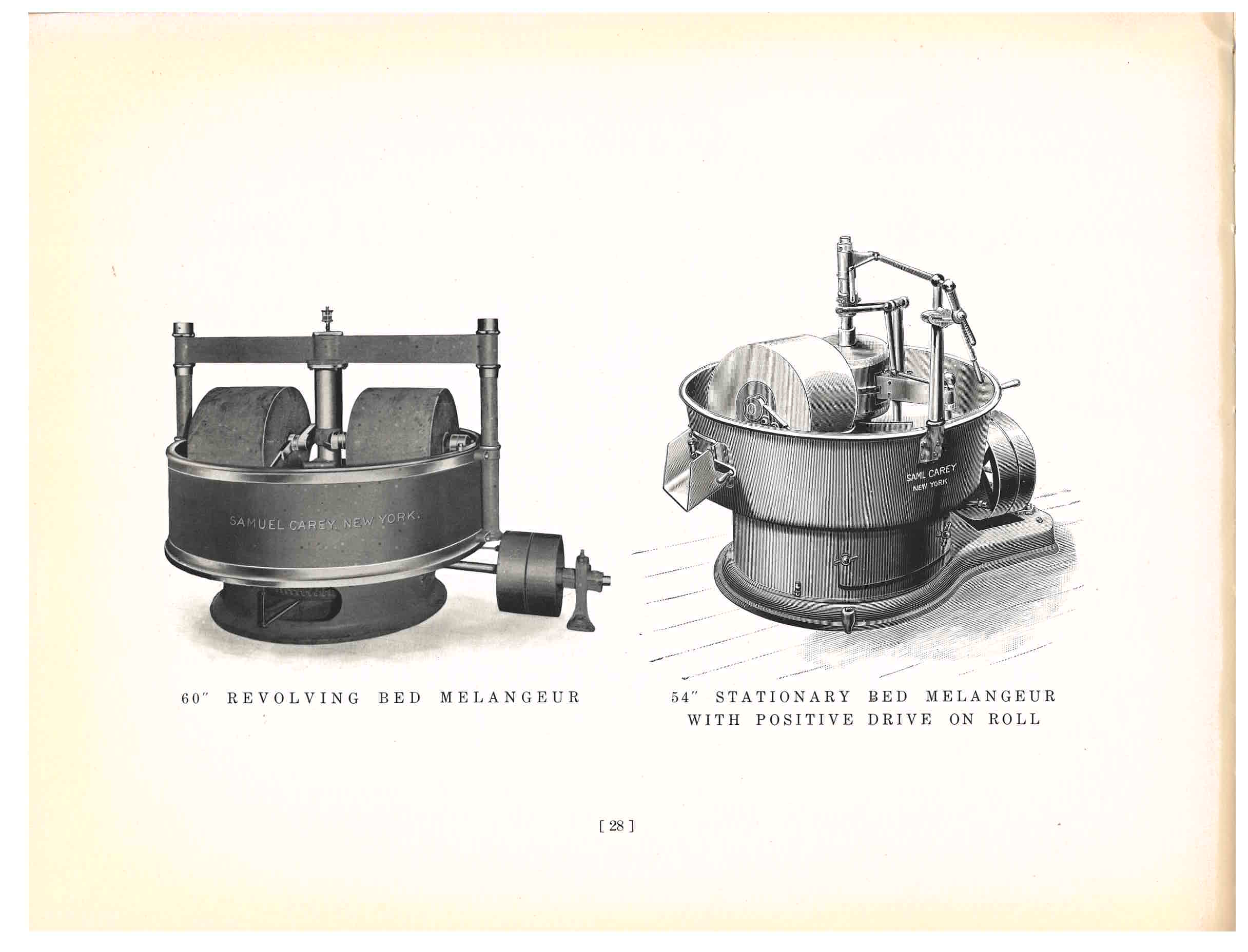

The 60 Inch Revolving Bed Melangeur accomplished the job of heavy paste mixing. As the catalog explained, its purpose was “to amalgamate the Cocoa Liquor and sugar together in such a form as to be received by the Finisher.” This particular melangeur (below left) included granite rolls and a granite bed. A handy feature was its deep pan. The inner, or revolving pan, extended upwards to within about 1 inch of the outer shell. This created a deep pan to prevent materials within the pan from spilling over the edge and creating waste. Underneath the pan was a large coil of pipe for heating.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 28, Melangeurs.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 28, Melangeurs.

Though this catalog recommended the Revolving Bed Melangeur for paste mixing, Samuel Carey also sold the Chocolate Paste Mixing Machine, illustrated below. It had the ability to create a heavy paste and was available in two sizes, a capacity of either 500 pounds or 1000 pounds.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 34, Chocolate Paste Mixing Machine.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 34, Chocolate Paste Mixing Machine.

Another section in this catalog refers to the process of refining and developing. It explains, that by these terms, they mean amalgamating, smoothing, and eliminating moisture which is especially important for confection with a finish, stroke, or ornament. One of the machines used for this process was the Nine Foot Coating Refiner, illustrated below. It had a capacity of 6500 pounds per batch.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 48, Nine Foot Coating Refiner.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 48, Nine Foot Coating Refiner.

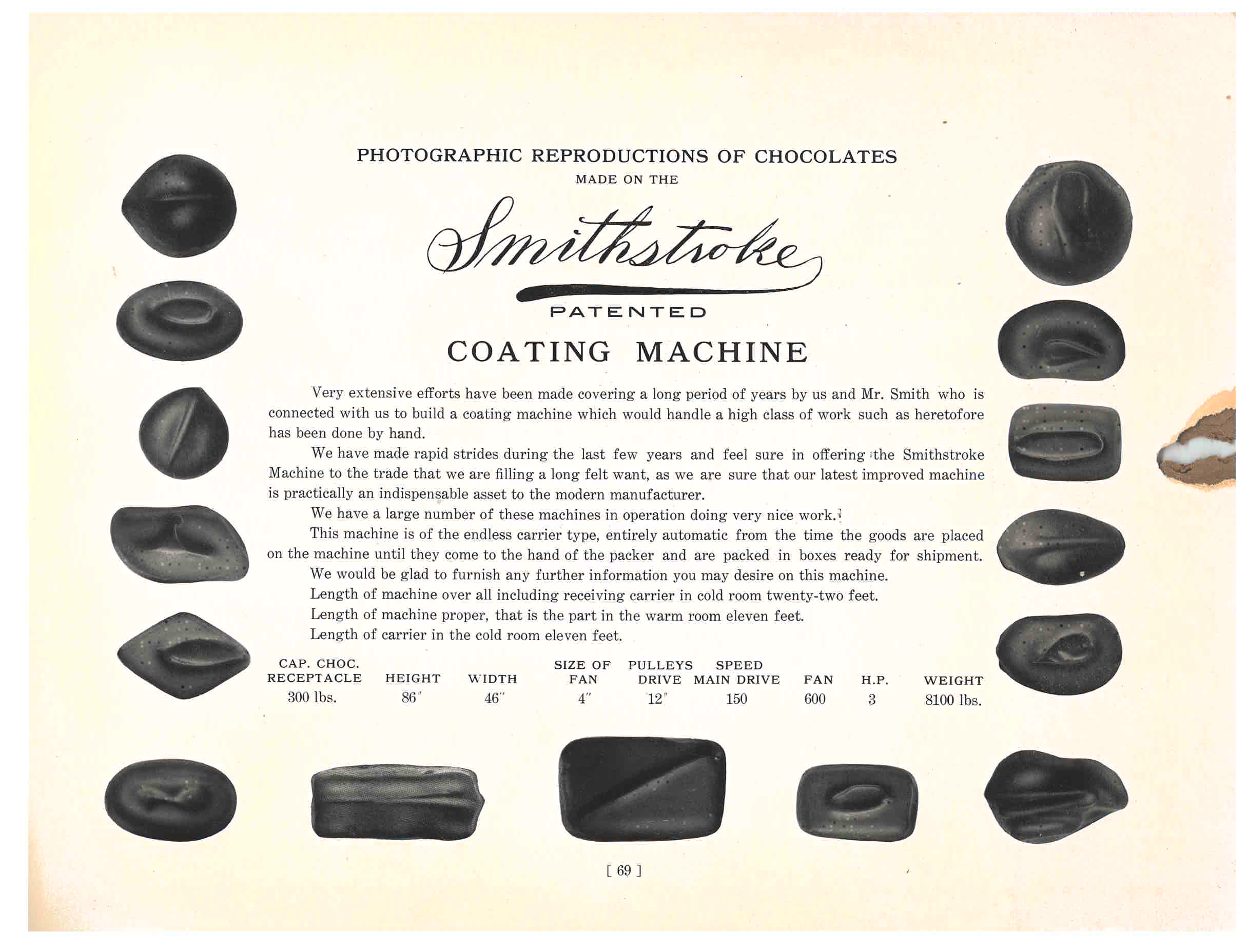

As explained on the page shown below, the company of Samuel Carey worked in collaboration with Mr. Smith to build the Smithstroke Patented Coating Machine. The goal was to build a coating machine that would produce the same type of product previously done by hand. The machine was completely automatic, from the beginning, when material was placed on it, to the end, when goods arrived in the hands of the packer who prepared the chocolates for shipping. Shown below are several photographic reproductions of chocolates that were made on the Smithstroke.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 69, photographic reproductions of chocolates made on Smithstroke Patented Coating Machine.

Samuel Carey, Brooklyn, NY. Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915), page 69, photographic reproductions of chocolates made on Smithstroke Patented Coating Machine.

Samuel Carey Chocolate Machinery (circa 1915) by Samuel Carey is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Looking for more candy-related literature? Take a look at this blog post about W. Hillyer Ragsdale’s correspondence courses from 1922 which taught students how to make and sell candy.

Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty Named Director of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is pleased to announce Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty as our new director, effective November 6. An expert in the stewardship, interpretation, and acquisition of collections, Evangelestia-Dougherty brings a rich background driving public outreach and cultivating robust print and digital collections across diverse subject matters.

Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, newly appointed Director of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. (Photo courtesy of Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty.)

Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, newly appointed Director of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. (Photo courtesy of Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty.)