Libraries' Blog

A Step Back into 1907 and Some Possible Gifts

As the holidays approach, children often dream of that perfect gift. What did a child dream of in the early 20th Century? Is it very different from today? Perhaps there are some similarities. We may find a few possibilities in this trade catalog.

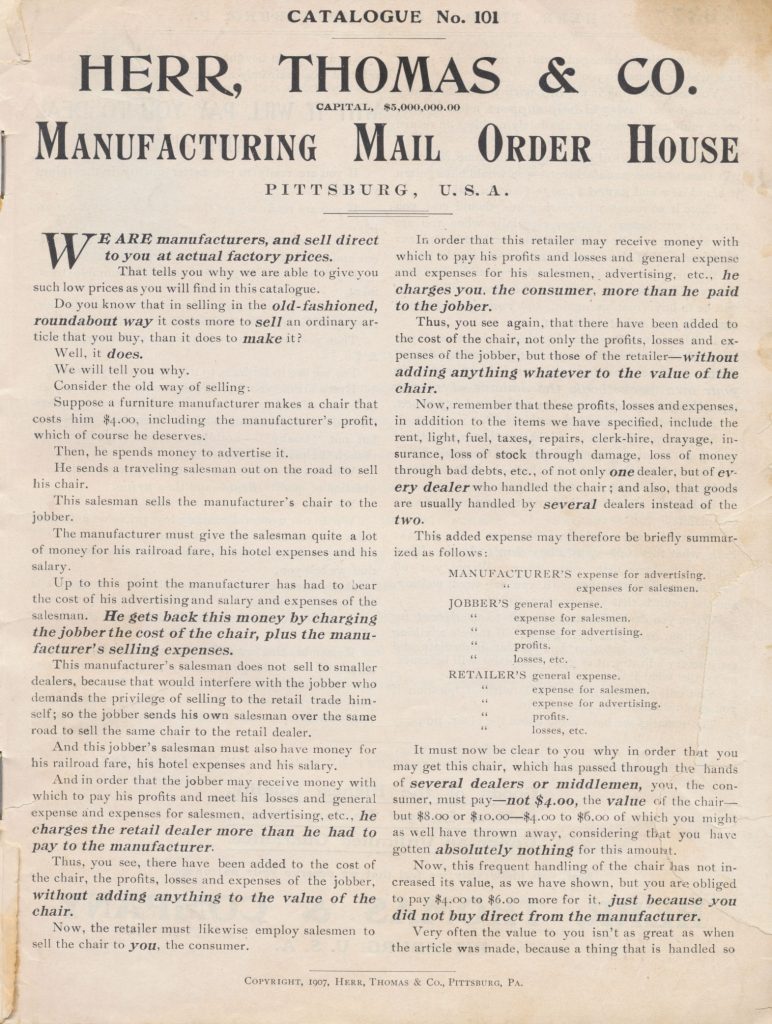

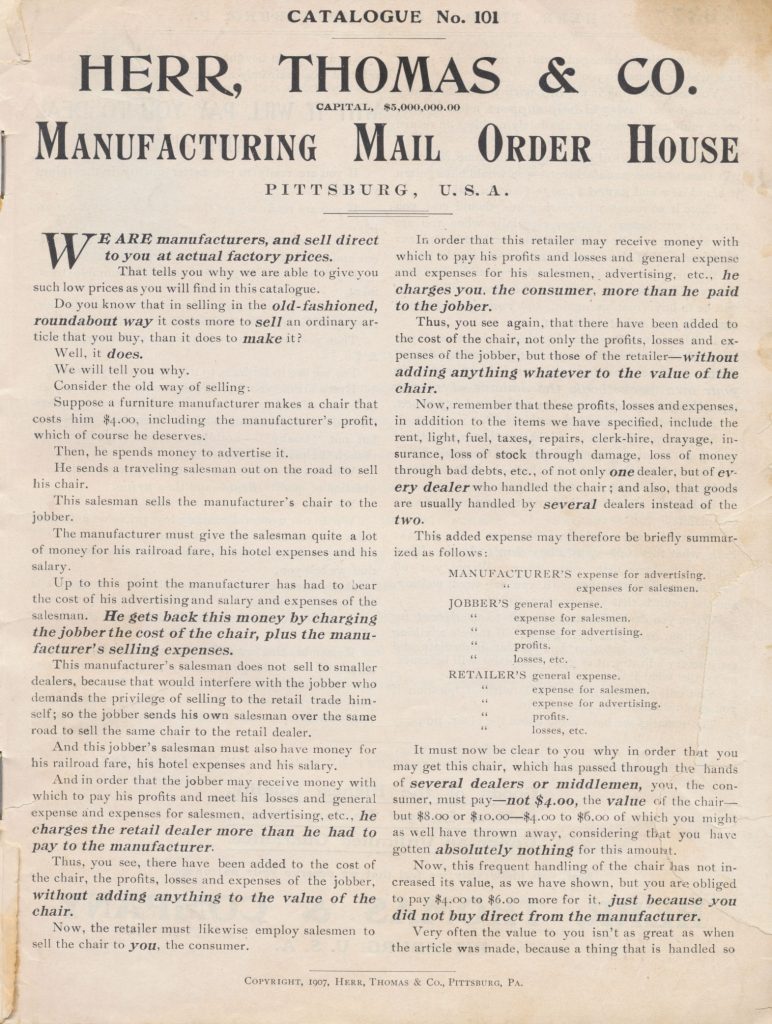

Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. provides a glimpse into toys from the past. Besides a variety of household items, it includes a few pages of toys for a young child along with other pages of items suitable for older children.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Dolls, go-carts, sleds, a tea set, and other toys are illustrated in this catalog. The doll, pictured below bottom left, is described as a “Dressed Doll.” Standing 16 inches tall, the doll’s dress was trimmed with ribbon and lace. White slippers and stockings along with a large hat trimmed with flowers and lace completed its outfit. This particular doll had sleeping eyes, and the face was made of French Bisque.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Dolls, go-carts, sleds, a tea set, and other toys are illustrated in this catalog. The doll, pictured below bottom left, is described as a “Dressed Doll.” Standing 16 inches tall, the doll’s dress was trimmed with ribbon and lace. White slippers and stockings along with a large hat trimmed with flowers and lace completed its outfit. This particular doll had sleeping eyes, and the face was made of French Bisque.

Today, children sometimes enjoy pushing dolls in a doll stroller. Judging from this catalog, it appears children in 1907 enjoyed that very same activity. The Doll’s Go-Cart shown below, bottom right, looks like what we, today, might refer to as a doll stroller. It was constructed of reed and split hickory with rubber tires and iron wheels, and its most noticeable feature was the attached parasol to shade the doll. This go-cart was a miniature version of a full-size go-cart. Perhaps, young children dreamed of their very own go-cart to push a doll while their mother pushed a sibling in a full-size go-cart.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 84, Dolls and Go-Carts.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 84, Dolls and Go-Carts.

Or maybe, a child dreamed of steering an “Automobile.” Pictured below, top left, the Automobile was described as a “plaything” to provide exercise and something a child “will never grow tired of.” It measured a little over one foot wide and just under three feet long with 12-inch diameter front wheels and 18-inch diameter back wheels. It was painted red with a maple floor and sheet iron sides. A handy feature was the foldable seat. By folding the seat in, the Automobile transformed into a level top wagon.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 85, Automobile, Wagons, Sleds, Printing Press, Child’s Tea Set, and Boy’s Tool Chest.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 85, Automobile, Wagons, Sleds, Printing Press, Child’s Tea Set, and Boy’s Tool Chest.

Children might have dreamed of preparing their own tea party or fixing a broken piece of equipment, just as they witnessed adults do. Both the Child’s Tea Set and Boy’s Tool Chest, illustrated above, were a child’s version of the real thing. The Child’s Tea Set came with enough plates, cups, and saucers for a tea party of six children. In addition to the individual pieces, a teapot, sugar bowl, and cream pitcher completed the set. The Boy’s Tool Chest, made of wood, consisted of 16 tools with a stationary tray for organizing tools. Some of the tools included in the chest were a hammer, large level, and brace bit.

An older child or teenager, perhaps an aspiring musician, might have wished for a musical instrument. Several instruments are shown in this catalog, such as the mandolin and accordion below and the cornet and trombone on another page. Musical accessories include the Music Roll, handy for carrying sheet music, the adjustable Music Stand, and the Leather Music Bag. This particular page also illustrates a Mandolin Cover, Guitar Cover, and Banjo Cover. Even though these are labeled “cover,” all three appear to be instrument cases. These covers were made of extra heavy duck and lined with red felt.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 82, Mandolin, Accordion, Instrument Covers (cases), Music Stand, Music Roll, Music Bag, Victor Disc Talking Machine, Zon-o-Phone, and Columbia Disc records.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 82, Mandolin, Accordion, Instrument Covers (cases), Music Stand, Music Roll, Music Bag, Victor Disc Talking Machine, Zon-o-Phone, and Columbia Disc records.

Others might have preferred jewelry. Perhaps, the Birthstone Ring, shown below, appealed to a teenager. Made of 14-karat filled gold in a plain band, it was mounted with the appropriate stone corresponding to a particular birth month. The examples of jewelry below also include a Child’s Ring with opal and a Baby Ring made of 14-karat rolled gold.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 80, Jewelry (pins, cuff links, cuff bottoms, rings) and Musical Instruments (cornet, trombone).

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 80, Jewelry (pins, cuff links, cuff bottoms, rings) and Musical Instruments (cornet, trombone).

Though not specifically a Christmas or Holiday catalog, consumers from 1907 might have stumbled upon gift ideas while perusing this catalog. Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. To learn more about the mail order aspect of this trade catalog and other items pictured in it, take a look at this post about writing supplies.

Meet the Archives: Get to Know Our Newest Colleagues

Earlier this week, we announced the exciting news that the Smithsonian Libraries and the Smithsonian Institution Archives have teamed up to become one, united Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. Sure, librarians and archivists deal in somewhat different mediums. Librarians care for and disseminate various forms of books and manuscripts, and archives are stewards of records—documents, photographs, audiovisual records, electronic records, and beyond. But the two also have so much in common. And the biggest similarity is that we are here to serve you. By joining forces, we hope our shared digitization programs, preservation resources, and reference services will better serve our audiences—now and in the future.

As we embark on the process of integrating both units, we’d like to share a bit about what our colleagues at the Archives do and how they do it.

This Smithsonian Institution Archives, one of sixteen archival repositories around the Smithsonian, collects, preserves, and makes available the history of the Smithsonian Institution. The 27 staff members of the Archives are broken up into five teams: archives information management, digital services, institutional history, preservation, and reference services. Below, learn a little about the kind of work each team does.

When a high-level or long-term Smithsonian employee retires, their records—papers, photographs, email, etc.—head to the Archives. The Archives and Information Management (AIM) team advises Smithsonian staff on the daily management of active records, provides guidance on the disposition of records, assists in the transfer of permanent records, and provides storage for temporary records. The AIM is responsible for arranging these new accessions and creating finding aids for researchers. One recent, interesting accession with a brand-new finding aid is Accession, 19-200: Lonnie G. Bunch III Papers, 1952-2010, which documents the long career of our current Smithsonian Secretary.

The Digital Services team is responsible for digitization, digital asset management, accessioning born-digital records and email accounts, web development, photography, and even social media. Your not-so-humble author is on this great and diverse team! How organized is your email account? Digital archivist Lynda Schmitz Fuhrig will be the judge of that. Think digitization is just a simple scan and upload? Our team would dare you to think again.

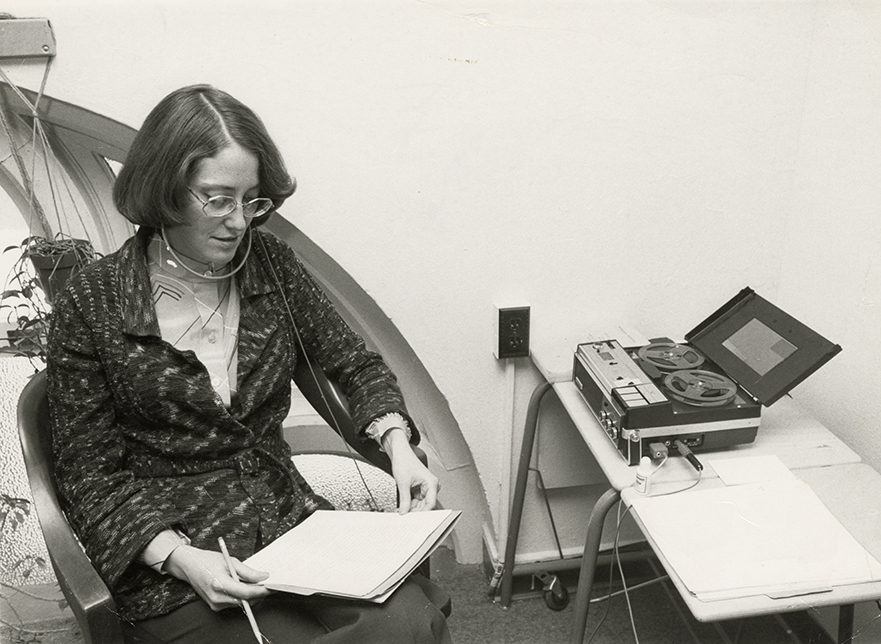

Historian Pamela Henson Listens to Oral History Interview, 1977, by Richard K. Hofmeister. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 371, Image no. 77-365-04A.

Historian Pamela Henson Listens to Oral History Interview, 1977, by Richard K. Hofmeister. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 371, Image no. 77-365-04A.

The Institutional History division is small but mighty. The team, led by historian Dr. Pamela Henson, has managed the Archives’ oral history program since 1973, develops and produces exhibits and webpages about the history of the Smithsonian, and answers reference questions for the public and the Institution’s administrators.

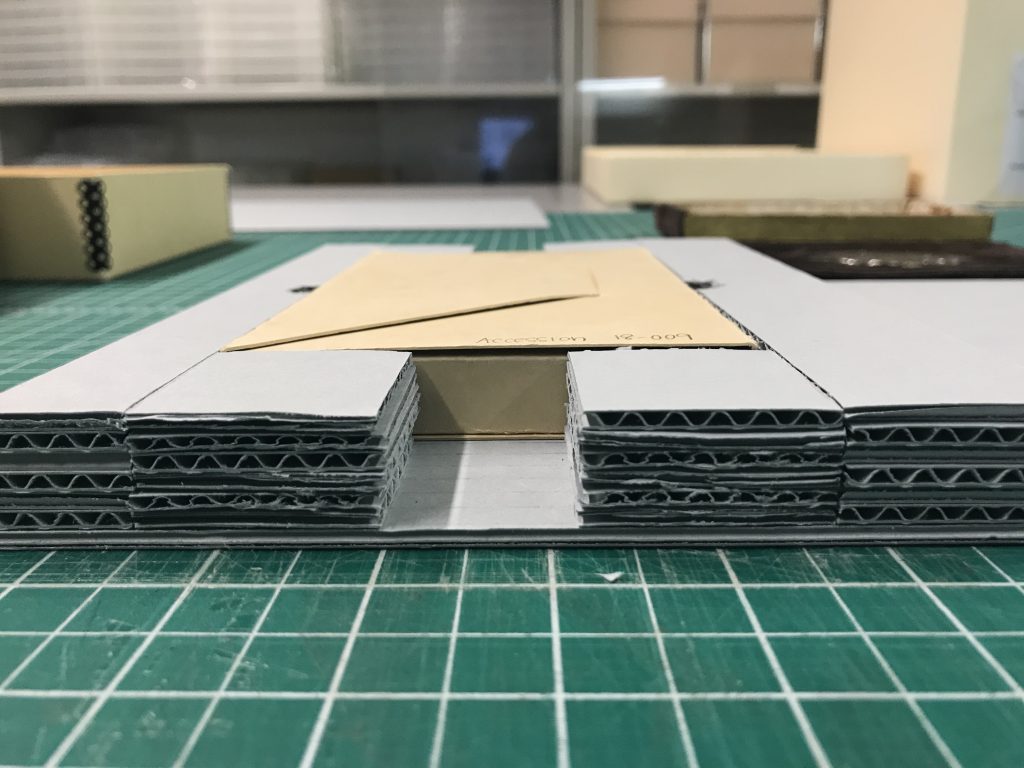

Readers of this blog are likely pretty familiar with book and paper conservation, but our Archives’ Preservation team is also responsible for storing, handling, and conserving a variety of other mediums. The team considers strategies for stabilization and access for photographs, audio and video recordings and film, and born digital records, like email, websites, social media, exhibit CAD drawings, and more. They fight crime (paperclip rust, decrepit tape, sticky note residue) and they wear capes (aprons).

And finally, our Reference team will likely be your first stop at the Archives. They help researchers locate materials and answer general Smithsonian history questions that come our way through the Reference Inquiry Form. The team tackles around 6,000 reference queries each year. What types of questions land in our inboxes? We have a whole blog series for that!

Detailed view of four-flap secured within the custom housing, 10 April 2019. Courtesy of Alison Reppert Gerber, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Detailed view of four-flap secured within the custom housing, 10 April 2019. Courtesy of Alison Reppert Gerber, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Two other staff members don’t quite fit in one team, but collaborate with each. RoseMaria Estevez is our administrative officer and Dr. Liz Harmon is our digital curator with the American Women’s History Initiative.

Curious to know more about the Archives? Check back on our social media channels for deep dives into their work and projects.

Introducing Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

The Smithsonian Libraries and Smithsonian Institution Archives have merged to become Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

“We are excited to combine the collaborative and innovative work of the Smithsonian’s archives and libraries to provide outstanding service to our stakeholders at the Smithsonian, the nation and the world,” said Scott E. Miller, interim director of Smithsonian Libraries and the Smithsonian’s chief scientist.

“Working together, we hope to increase and enrich online content, reach new audiences and provide greater access to researchers of all types around the world,” said Tammy L. Peters, interim director and supervisory archivist at Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Through this new partnership, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives houses nearly 3 million library volumes in subjects ranging from art to zoology and 44,000 cubic feet of archival materials chronicling the growth and development of the Smithsonian throughout its history. The organization will better serve the growing needs of the global research, curatorial, library, archival and academic communities.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is a major specialized research library system composed of 21 branches located in the Smithsonian’s museums and research centers. Its holdings include 50,000 rare books and manuscripts, complemented by more than 120,000 electronic books, journals and databases, and an expert staff who daily serve the information needs of the Institution’s scientific, research, exhibition and education colleagues, as well as in-person and online scholars and visitors from around the country and world.

The Libraries and Archives also serves as the Smithsonian’s institutional memory, documenting the history of the Smithsonian from its founding in 1846 to the present, and supports the Smithsonian community, scholars and the public by acquiring, evaluating and preserving the records of the Institution and related documentary materials. The organization manages the care, storage and retrieval services for the Institution’s records in a wide variety of analog and digital formats.

Together the Libraries and Archives will provide digital infrastructure more broadly, expanding critical digital preservation and research data management. It will continue offering creative programming, events, exhibitions, internships, fellowships, educational resources and funding opportunities.

Dedicated to fulfilling Smithsonian’s mission for “the increase and diffusion of knowledge,” the Libraries and Archives is committed to the 21st-century needs of researchers, curators, educators and learners of all ages. It encompasses 137 staff members and is supported by an advisory board of 15 leaders from around the United States.

About the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an international system of 21 library branches and an institutional archives. It maintains a collection of almost 3 million volumes and 44,000 cubic feet of archival materials. The Libraries and Archives serves as an educational resource for the Smithsonian Institution, the global research community and the public. Locations are in Washington, D.C., Maryland, Virginia, New York City and the Republic of Panama. Find out more at librariesarchives.si.edu.

#AskAConservator Day Recap

We’re always in awe of our book conservators. Whether it’s mending a torn cover, giving a 16th century book the “full treatment”, or helping with international disaster relief efforts, they amaze us with their skill and expertise. On November 18th, our team shared their knowledge with the Twitterverse via #AskAConservator Day. This daylong chat was organized by the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) to help create awareness of the field of conservation and engage with the public. Our own conservators jumped at the chance to participate.

Our conservation experts included:

- Vanessa Haight Smith, Head of Preservation Services

- Katie Wagner, Senior Book Conservator

- Keala Richard, Conservation Technician

- Donald Stankavage, Conservation Technician

- Daniel Viltsek, Book Conservator

Our team answered over a dozen questions and their responses reached over two million twitter accounts! We’ve compiled most of the conversation in to one Twitter moment but we’ve also included a quick recap of our favorite responses below. We hope you find them helpful in caring for your own collections.

Q: I have an old family notebook in which the original writing has been obscured by scrapbook newspaper cuttings pasted over it. What’s the best way to remove the cuttings to reveal the original writing?

A: There are 3 common approaches to removal – heat, humidity, & solvents, depending on type of glue & condition of item. It’s a more complicated than it initially looks! We recommend looking for an AIC member in your area!

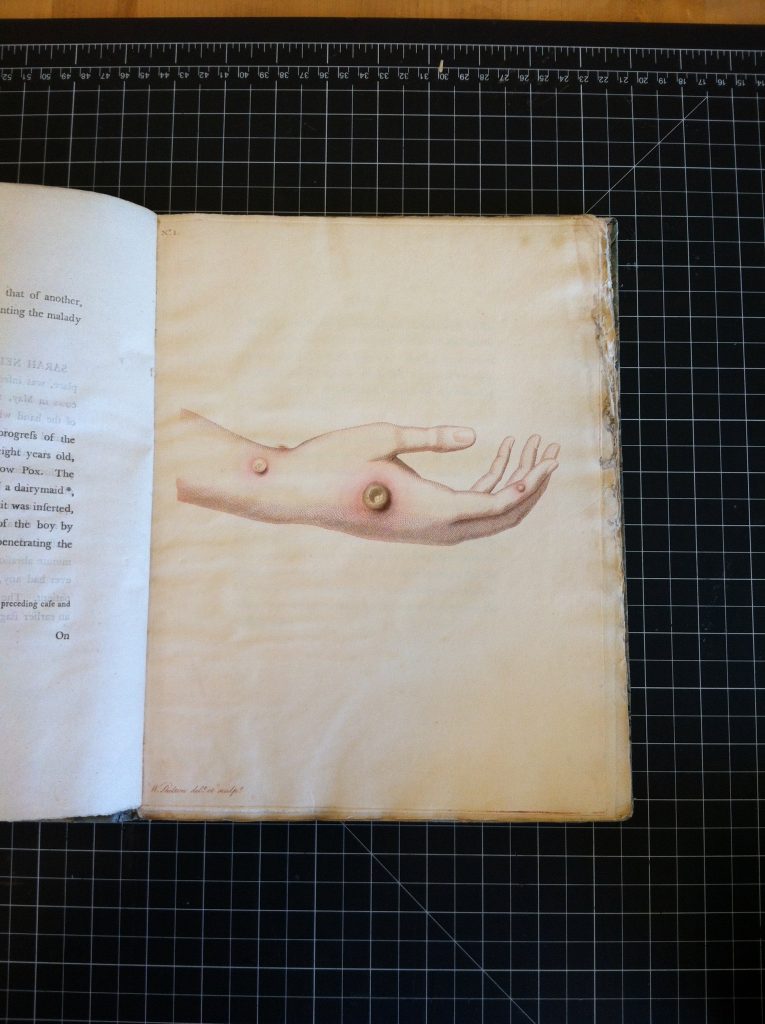

Q: What is your favorite thing you have ever worked on?

A1 (from Katie Wagner): Edward Jenner’s book about smallpox vaccine has it all: a compelling story – Jenner was the father of modern immunology, beautifully illustrated & hand colored with sanguine & involved array of conservation treatments: https://s.si.edu/3pNuExV

Plate from Edward Jenner’s An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae

Plate from Edward Jenner’s An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae

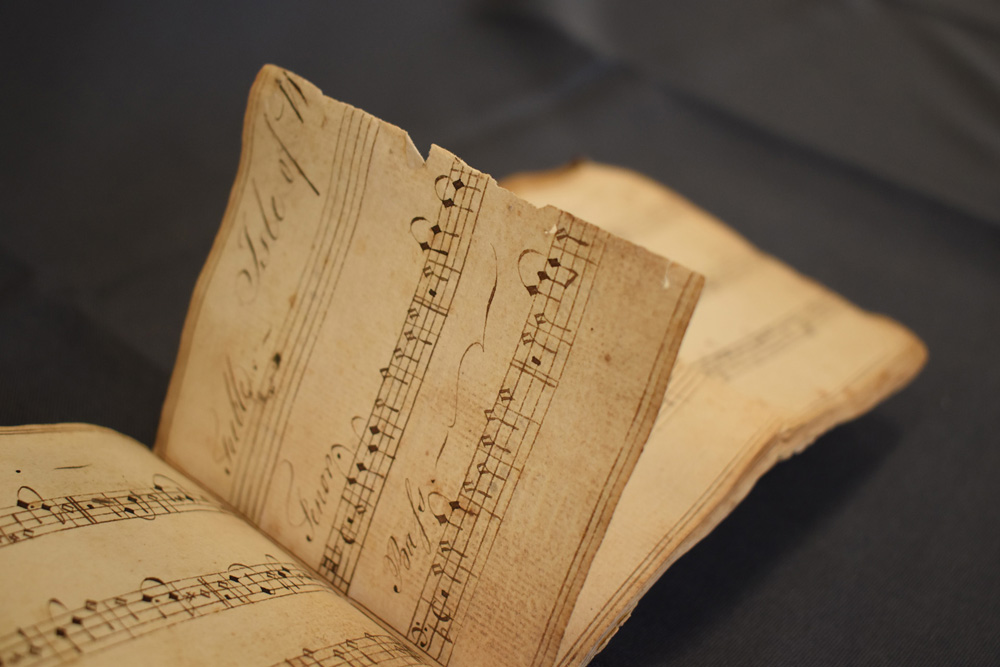

A2 (Vanessa Haight Smith): Repairing sheet music used by a fifer during the War of 1812: https://s.si.edu/2UGeCY1

James Bishop’s musical Gamut of 1766

James Bishop’s musical Gamut of 1766

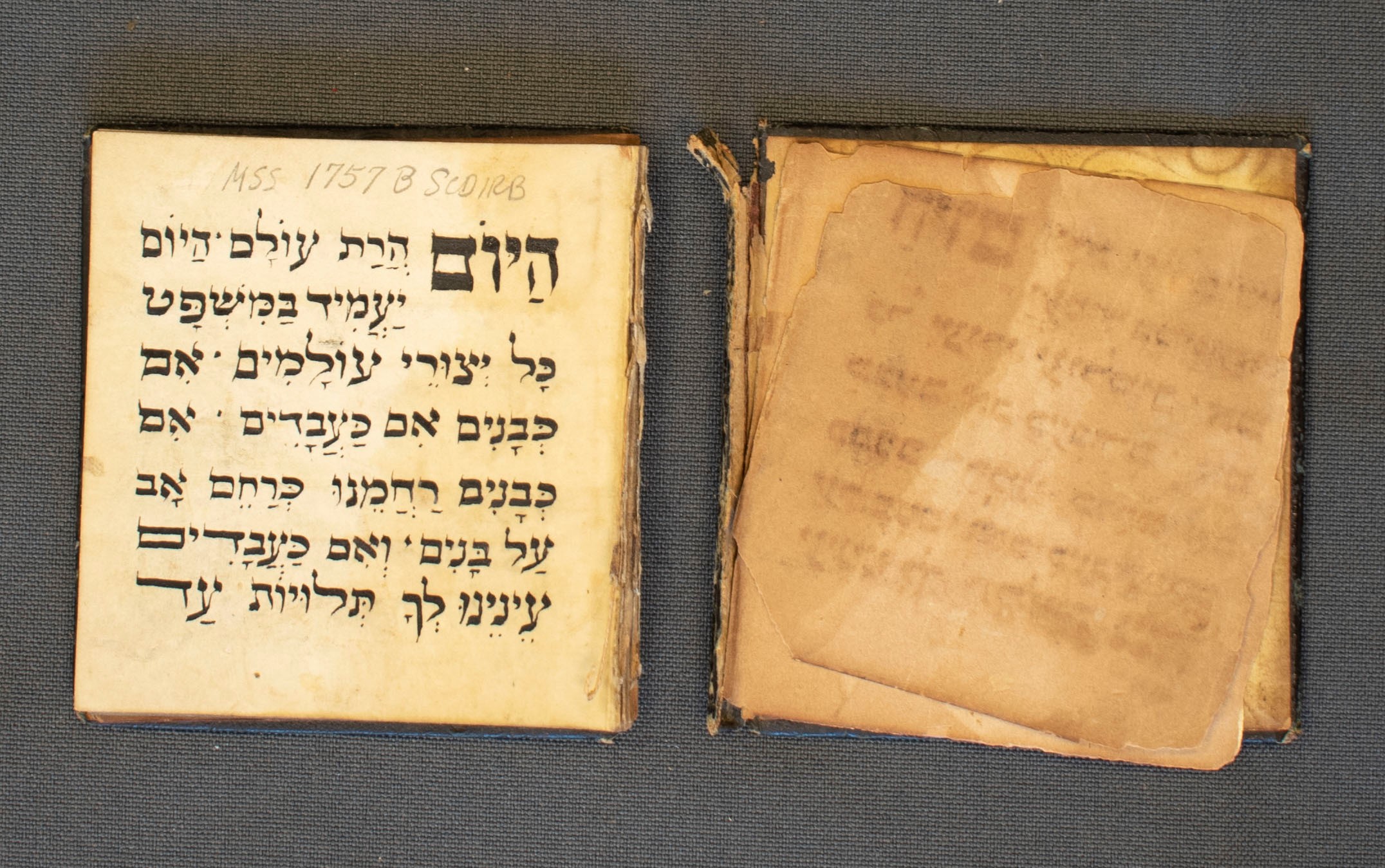

A3 (Daniel Viltsek): I really enjoyed treating a Hebrew prayer book for Rosh Hashana- It’s a small pocket size manuscript handwritten in ink on parchment. It was an especially personal prayer book, created for a particular moment in the Rosh Hashana service.

Hebrew prayer book for Rosh ha-Shanah [manuscript] [ca. 1920?]

Hebrew prayer book for Rosh ha-Shanah [manuscript] [ca. 1920?]

Q: Best way to store fold out maps/diagrams to prevent them from tearing and creasing. Also, how do you smooth out maps that have been poorly folded?

A: For foldouts, it’s best to humidify and flatten. There is a great blog post by a former technician: https://s.si.edu/3lMPye6

Q: In an aging book, what’s the best thing to keep the brown areas from getting worse?

A: No easy answer to preventing browning, unfortunately. Keeping materials in areas with proper temperature and humidity control (at/ a little under 70 degrees Fahrenheit and at or just under 50% RH) is the best bet. No attics or basements! And keep away from direct or strong sunlight.

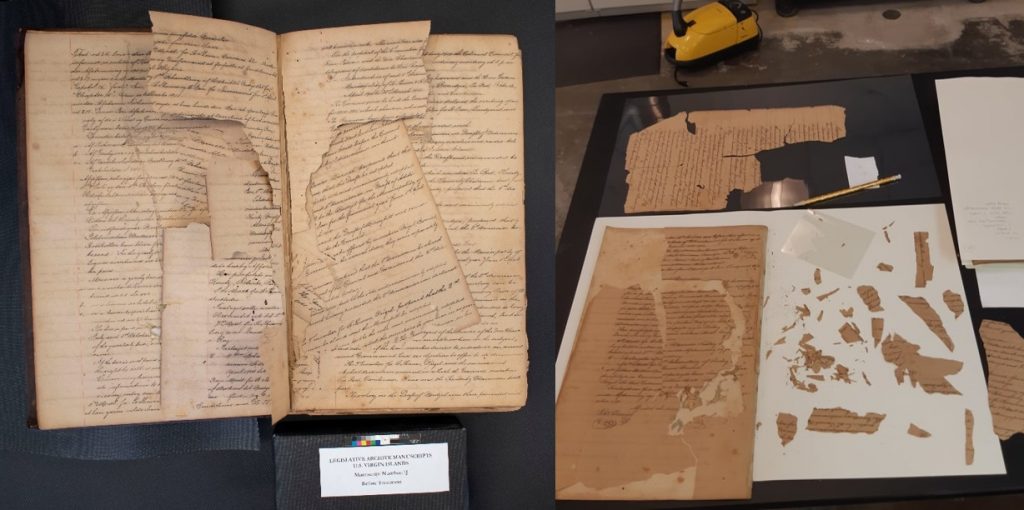

Q: Have you ever had to work on something so fragile you were afraid to even touch it? What did you do and how did you do it?

A: Our team recently worked on legislative records from the U.S. Virgin Islands where the paper was like potato chips in places! https://s.si.edu/36MgPqB

Pages of the first journal of handwritten legislative journals from the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Pages of the first journal of handwritten legislative journals from the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Still curious about conservation? Explore these recent blog posts from our Book Conservation Lab.

Setting the Thanksgiving Table, 1915 Style

Families have different Thanksgiving traditions. Some may prefer a casual dinner while others plan formal events. Either way, a Thanksgiving meal requires many pieces, everything from individual place settings to serving dishes. How might Great Grandma have set her table for a special occasion in 1915? This trade catalog may give us a glimpse.

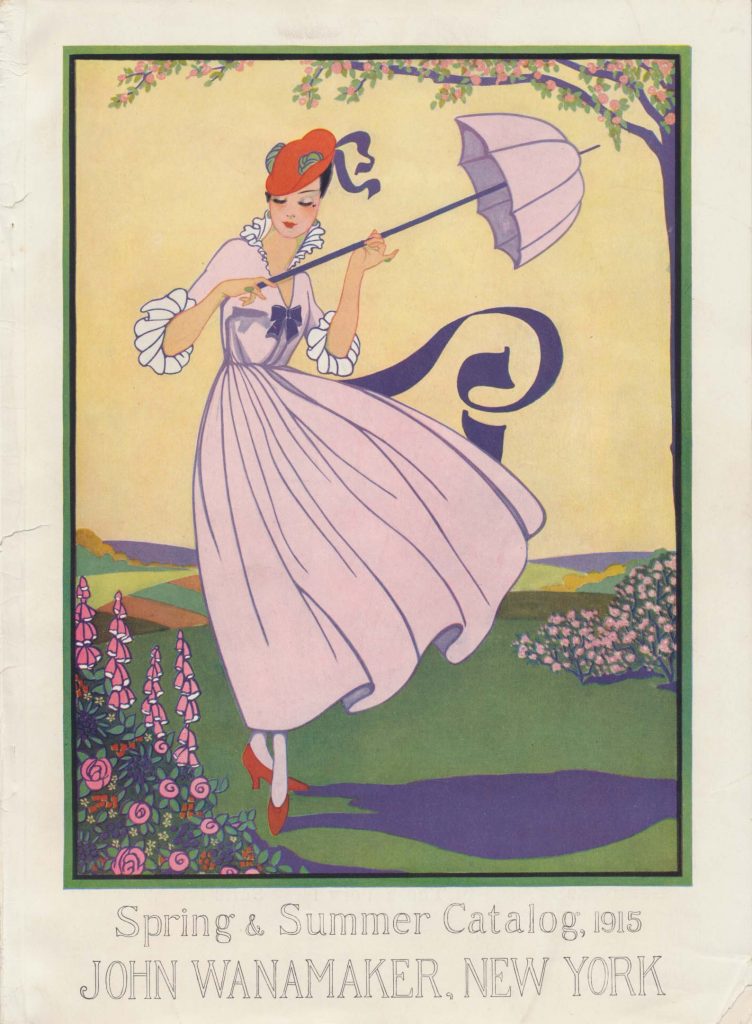

The trade catalog is titled Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) by John Wanamaker. Though the clothes pictured in it are suitable for Spring and Summer, the kitchen and cooking necessities work at any time of year. And, that includes possible items, minus the food, for a Thanksgiving or holiday dinner. The home furnishings section illustrates furniture, silverware, dinnerware, and linen. Let’s take a closer look.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, front cover.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, front cover.

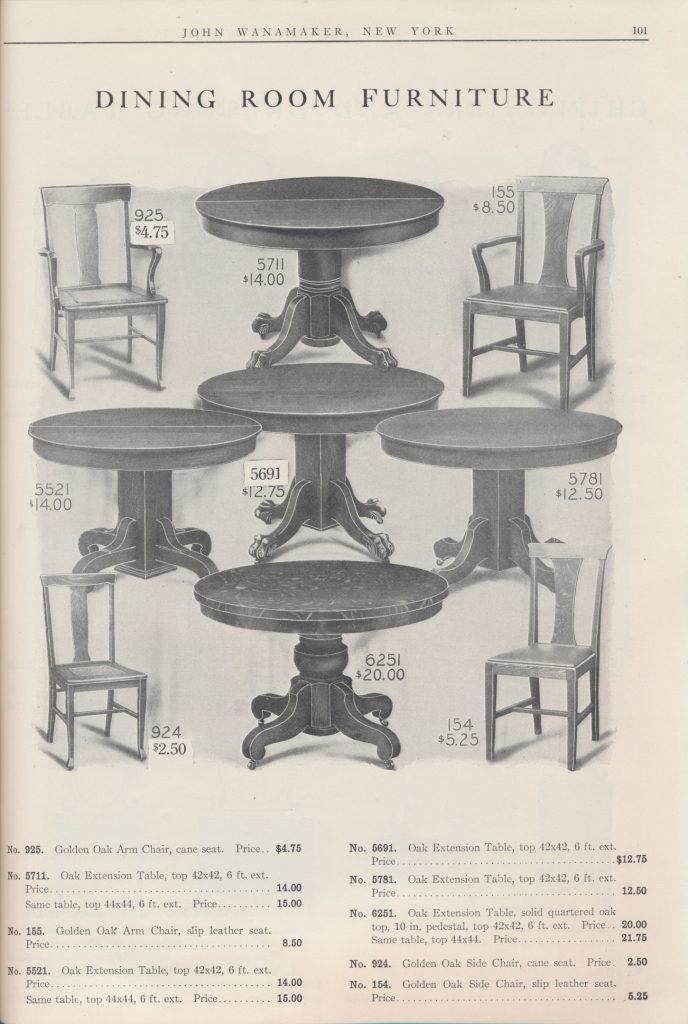

A large enough table would have been essential. The dining room tables below were made of oak. The Oak Extension Table No. 6251 (below, middle bottom) had a solid quartered oak top with a 10-inch pedestal. Its six-foot extension would have been especially useful during the holidays to create extra space for visitors. The Golden Oak Chairs were available as either arm or side chairs with a cane seat or slip leather seat. An example of a cane seat is shown on No. 924 Golden Oak Side Chair (below, bottom left). A slip leather seat is pictured on No. 155 Golden Oak Arm Chair (below, top right).

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 101, Dining Room Furniture (tables and chairs).

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 101, Dining Room Furniture (tables and chairs).

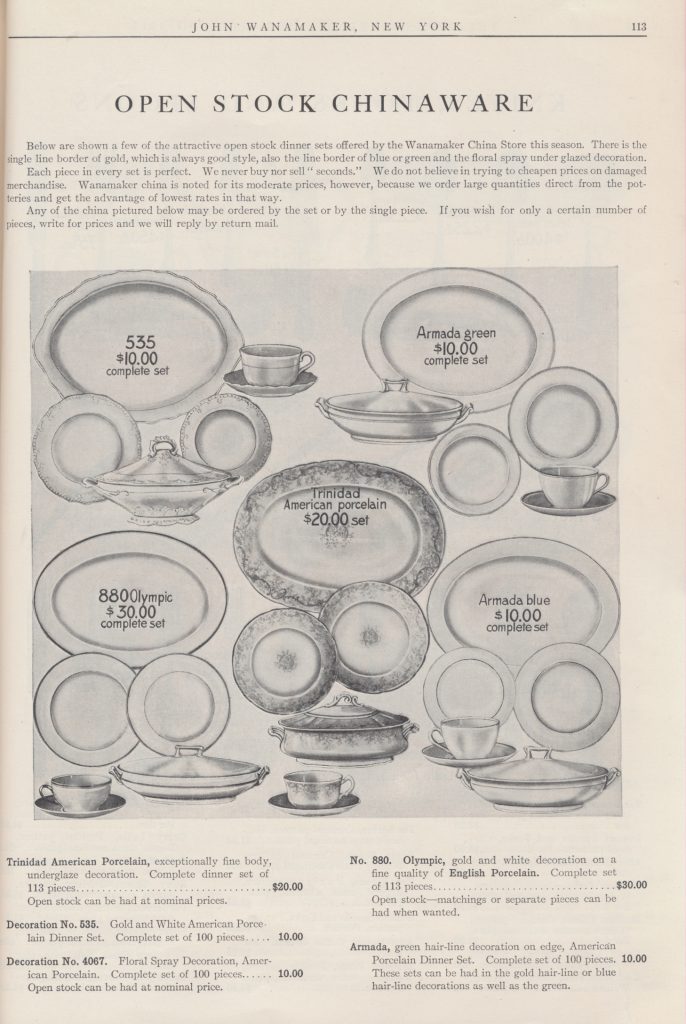

Perhaps, in 1915, Great Grandma used plates such as these below. John Wanamaker sold several designs, both simple and decorative patterns. Some pieces had a single lined gold border while others were available with blue or green lined borders. Another option was floral spray under glazed decoration. These dinner pieces were sold separately or as a set.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 113, Open Stock Chinaware dinner sets.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 113, Open Stock Chinaware dinner sets.

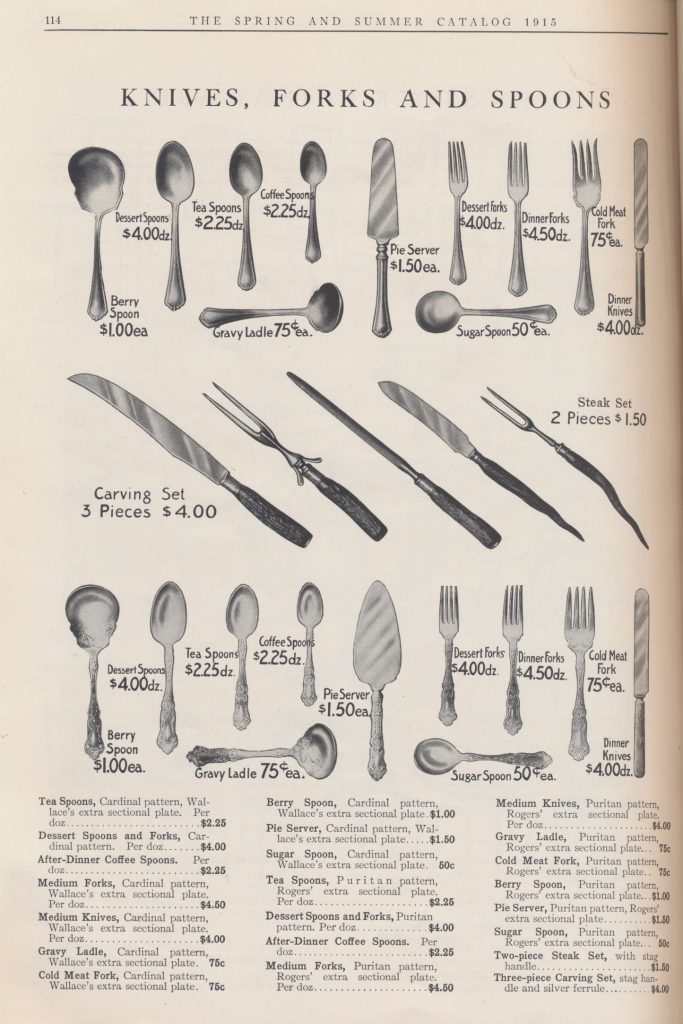

Whether casual or formal, each person needs an individual place setting with knife, fork, and spoon. John Wanamaker offered both individual and serving utensils for dinner and dessert. The dinner and dessert forks, dinner knives, teaspoons, coffee spoons and serving utensils, including pie servers, sugar spoons, and gravy ladles, are illustrated in two different patterns. These are Cardinal or Puritan. A three-piece carving set for the main course was also available but without a choice of design.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 114, Knives, Forks, Spoons, and Serving Utensils.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 114, Knives, Forks, Spoons, and Serving Utensils.

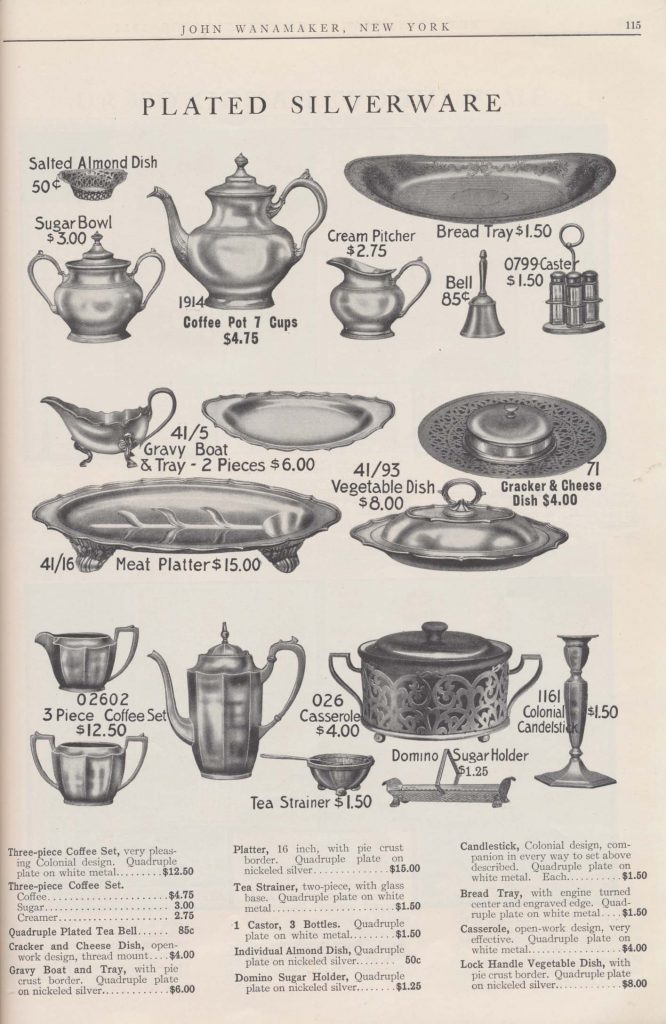

Speaking of serving utensils, what might Great Grandma have used for her serving dishes? Perhaps, she displayed the dinner’s main course on the Meat Platter pictured below. The Gravy Boat and Tray, to go along with the Gravy Ladle mentioned previously, are shown just above the Meat Platter. As for the side dishes, corn or mashed potatoes might have been served in a Vegetable Dish with cover, like the one shown directly to the right of the Meat Platter. Warm bread was probably passed around the table on a Bread Tray (below, top right).

After dinner, perhaps family and friends chatted over coffee and dessert. The three-piece coffee set (below, top left) consisting of a seven-cup Coffee Pot, Sugar Bowl, and Cream Pitcher might have come in handy.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 115, Plated Silverware and Serving Dishes.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 115, Plated Silverware and Serving Dishes.

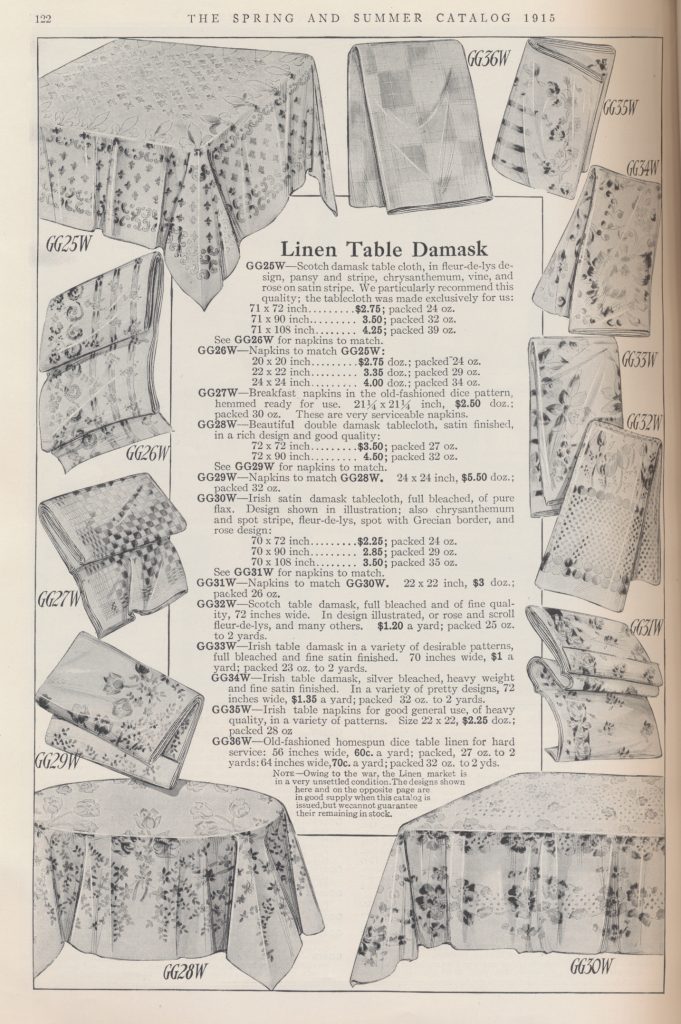

John Wanamaker also sold a variety of cloth napkins with matching tablecloths. These designs included floral patterns. The note at the bottom of the page is a reminder that this particular catalog was printed during World War I. It reads, “Owing to the war, the Linen market is in a very unsettled condition.” It continues by explaining that the linens shown were in stock at the time of printing of the catalog but not guaranteed to remain in stock.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 122, Linen Table Damask, including tablecloths and napkins.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog, 1915, page 122, Linen Table Damask, including tablecloths and napkins.

Just like today, some customers might have preferred shopping from the convenience of their home while others chose to shop in-person at the department store. In 1915, all of these items and more were available via the store’s mail order service. According to this catalog, shoppers also had the option of wandering a 16-story building located in New York focused mostly on home furnishings.

Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) and other trade catalogs by John Wanamaker are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in more tableware from the past? Explore table settings from 1899-1900 in a Joel Gutman & Co. trade catalog via this post.

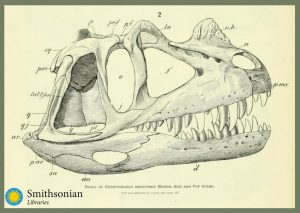

Researching Chinese Literati Painting in the Freer Sackler Library

The summer of 2020, as part of a Smithsonian Libraries’ Wikidata Pilot Project and in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Library offered an all-virtual internship project. Interns selected for the Chinese Ancestor Portraits Wikidata Project spent six weeks researching the individuals represented in the Chinese portrait collection of the National Museum of Asian Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. The interns then added this information to the Wikidata page for the person. As one of the team members of the Chinese Ancestor Portraits Wikidata Project, I was first intrigued by why Wang Huan, a plain clothed fragile old man was chosen as one of the ancestors portrayed in this painting collection. After a literature research, I realized he was the most ideal model for a portrait painting that represented Confucian virtues and showcased a new painting genre, “literati painting”.

Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty. “Sheep and Goat”. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment. F1931.4

Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty. “Sheep and Goat”. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment. F1931.4

Chinese art historian Jerome Silbergeld once observed, “Literati painting may sound strange to the foreign ear, to anyone not yet introduced to Chinese history and art, challenging readers to comprehend how [to understand] this rubric, peculiar to China and tied to China’s civil structure, its gentlemen-painters and its civil service system.” To understand literati painting it is important to know what made literati painting peculiar to painting of the Song dynasty (960-1279) and why it became the predominant genre of Chinese painting ever since, even today.

Gu Kaizhi, attr. Southern Song. “Nymph of the Luo River”. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1914.53

Gu Kaizhi, attr. Southern Song. “Nymph of the Luo River”. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1914.53

Prior to the Song dynasty, court politicians were mainly aristocrats who inherited their titles from their families. In the Song dynasty a new meritocracy replaced the old hereditary system. Civil court positions could be held by anyone, even commoners, who competed in the civil service exam, excelled and were chosen. Among these scholar-officials a new painting tradition developed, breaking away from the earlier tradition of pictorial representation primarily concerned with “form-likeness,” reflecting what the eyes see in reality. As these scholar-amateur or scholar elites entered the painting world, they brought with them a deeply rooted appreciation for poetry and calligraphy, an aesthetic that valued the portrayal of individual feelings over realistic resemblance. These non-professional scholar-painters claimed that they didn’t have the traditional painters’ vigorous training, skillful techniques, or expensive materials, but worked more on expressing their feelings, political views, ideology and personal struggles. They painted only for their own personal enjoyment or that of their friends, with their focus on “capturing the spirit beyond form” as expressed by the great Eastern Jin dynasty painter, Gu Kaizhi (c. 344-409). The absence of colors and structural composition was calculated to reflect this emphasis on essence over physical resemblance. Even though individualism seemed to be at the core of literati painting, the traditional Confucius conformity was never absent from their paintings. The Confucius virtues were more dominant in Song literati painting than ever before.

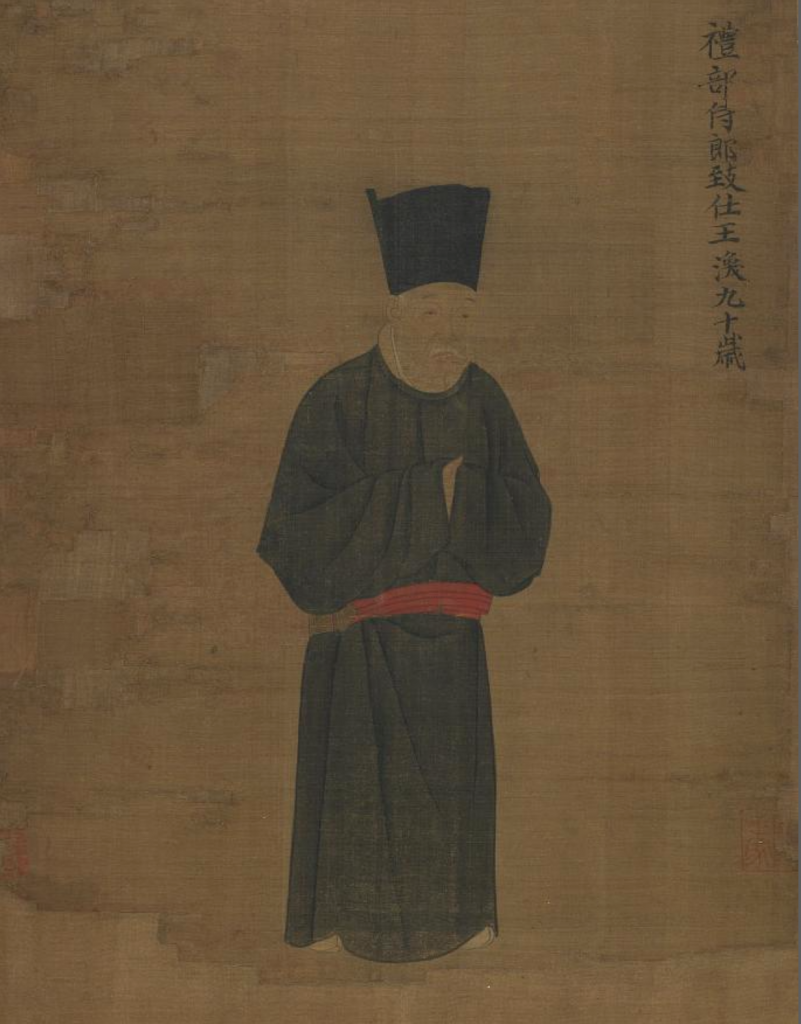

In the Confucius context, longevity was seen as a proof of virtue. The Classic of History asserts that “Heaven gives long life to the just and to the intelligent”. Within the group of ancestor portraits that is part of the Freer Sackler Library’s Wikidata internship project is a portrait of Wang Huan, a retired Song court official. There is little biographical information on him, but from an inscription added to the painting at a later date we know the portrait is an image of him when he was 90 years old and that he was a vice-deputy of the Ministry of Rituals upon his retirement, some 20 years previously. Leisure retirement from politics was hard to attain in Chinese history. People often described political life as “walking on a thin layer of ice”. Some were forced into retirement, some retired out of fear of political retaliation, only a few enjoyed a truly peaceful retirement endorsed by the emperor. Originally, Wang Huan’s portrait was part of an album of five octogenarians whose ages ranged from 87 to 92 years old. A thousand years ago it was rare for people to live to 70 years of age and almost impossible to survive the cut-throat political life to live to an advanced age into an enjoyable retirement. That achievement was admired and respected. The image of an old respected, retired official was employed metaphorically to express literati virtues of integrity, elegance and death. Wang Huan’s calm face and black silk clothes reflect the Song taste: elegance, dignified and subdued.

Anonymous. Northern Song, “Portrait of Wang Huan”, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment. F1948.10

Anonymous. Northern Song, “Portrait of Wang Huan”, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment. F1948.10

Wang Huan’s career and long retirement, laden with cultural activities, were the ideal model for the Song literati to follow. In him, the Song literati saw the core elements that they admired and respected: longevity, dignity and subtlety. Literati painting undoubtedly became the best vehicle that could deliver these characters and Wang Huan was chosen to be the representative and he became truly immortal.

Those interested in Song literati painting might find the following publications useful:

Fang, Wen. Beyond Representation: Chinese painting and calligraphy, 8-14th century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1992.

Lawton, Tom. Chinese figure painting. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art. 1973.

Lippit, Yukio. “Urakumi Gyokudo: an intoxicology of Japanese literati painting”, Studies in the History of Art—National Gallery of Art (2009), pp. 167-187.

Silvergeld, Jerome. “On the origins of literati painting in the Song Dynasty” in A companion to Chinese Art. 474-498. Edited by Martin J. Powers, Kathrine R. Tsiang. New York: John Wiley & Son. 2015.

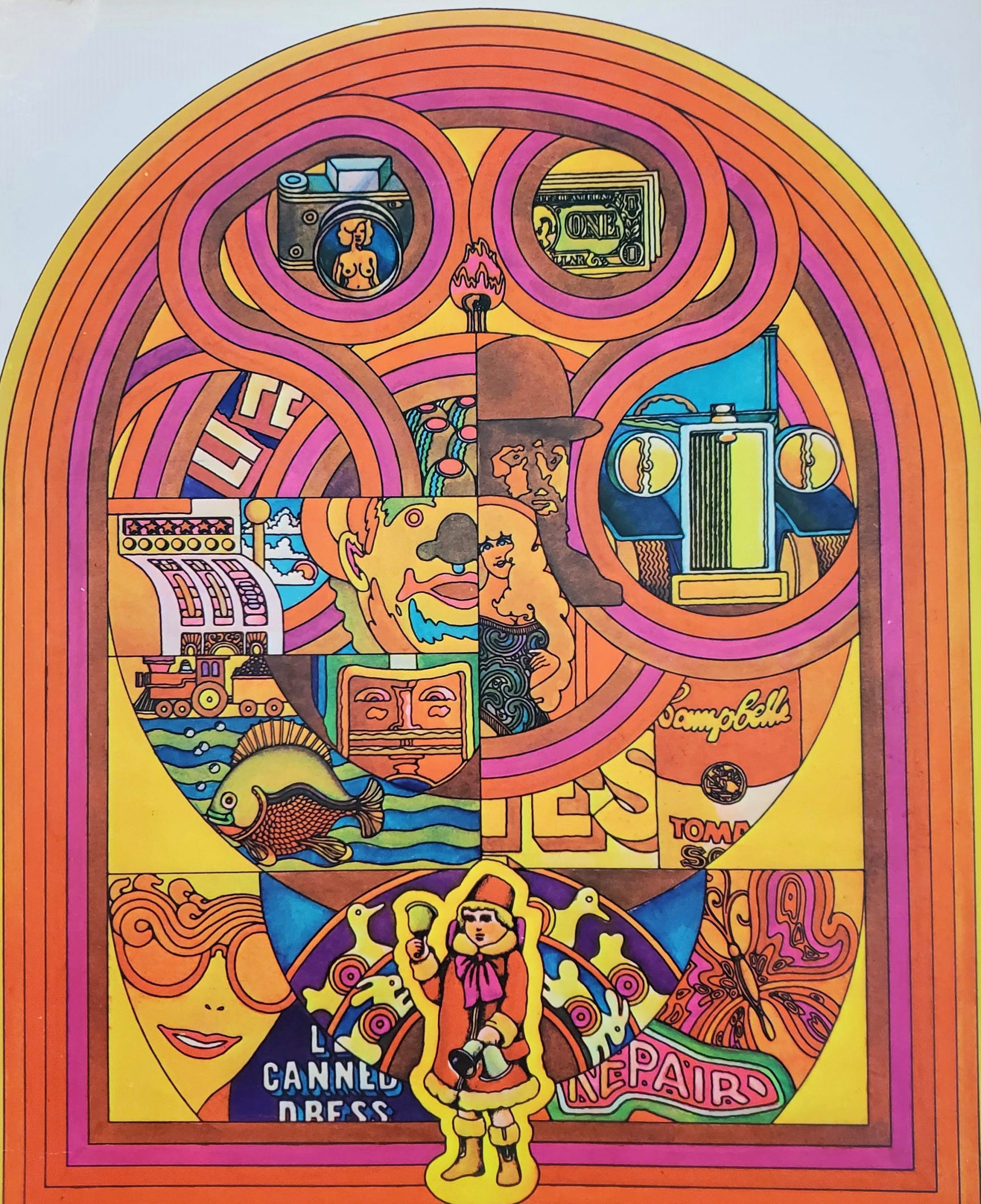

Open Access Week – How is the Smithsonian Doing?

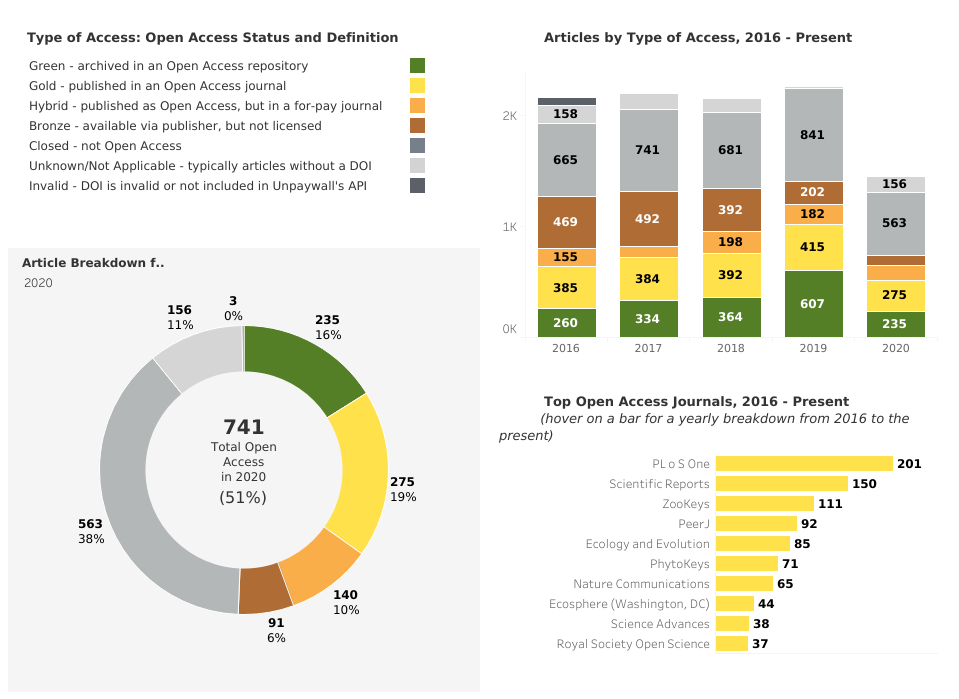

In celebration of this year’s annual Open Access Week, the Smithsonian Research Online team will be releasing a new dashboard on our statistics page that includes data about the openness of Smithsonian research publications. As the official record of scholarly publications for the Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Research Online is in a great position to analyze this data and help the Institution reflect, participate, and learn more about the scholarly output of the Smithsonian research community.

What is Open Access?In its most broad definition, open access is an effort to make things available to anyone without restrictions, from sharing images with a CC0 license to making sure wilderness is reachable to the public. Smithsonian Open Access is a strong example, with now over three million images online and freely available since its launch in February. Open access in this post is a more specific use of the phrase, describing the ways research publications (specifically journal articles) are made accessible free of charge and open to anyone.

The primary goal of open access is that any reader can access scholarship without paying for articles or having to belong to a library that pays for subscriptions to journals. And as you can see from our dashboard, between 50 and 65 percent of recent Smithsonian-authored journal articles we have tracked in the past few years are in this category. Open access has opened (literally) a world of scholarship to a much broader audience, reducing financial barriers to access academic works.

Dashboard of Smithsonian-authored articles and Open Access

Dashboard of Smithsonian-authored articles and Open Access

To authors, librarians, publishers and other actors in the research lifecycle, there is a lot more to open access than just the access part. There are many roads a research article could take to become open. Sometimes, that road involves tolls in the form of article processing fees. These are fees paid by the authors or their institutions to cover the costs of publishing. The economics of open access publishing are a fascinating topic for another time, but suffice it to say, just because an article is free to a reader does not mean there hasn’t been a transaction of money along the way.

Where is the Data From?Like any kind of analysis, this dashboard required some thinking about data sources. For years, the Directory of Open Access Journals has been a great resource for tracking which journals are open access. More recently, the incredible team at Our Research has launched Unpaywall.org, an open database of over 27 million free scholarly articles. These data sources both have APIs, allowing for quick retrieval of metadata about specific journals and journal articles. Of course, getting a good determination of open access starts with the completeness of our data. We invest in making sure that our metadata has common identifiers like ISSNs for journals and DOIs for articles. These identifiers are the underpinnings of the infrastructure that makes such dashboards possible. To ease an already complicated set of conditions, we went with Unpaywall’s indication of which open access method was “best,” so the dashboard does obscure the fact that an article can be open in more than one way (i.e. you can put an article from an open access journal in a repository, making it both “gold” and “green”).

What do the different types of access mean?Our colorful categories match those used by Unpaywall.org, with a couple additions:

- Gold open access applies to articles published in journals where all content is licensed as open by the journal publisher from the start.

- Hybrid open access occurs when a publisher of an otherwise subscription-only journal makes content available as open access articles.

- Bronze open access is when the articles are available but ambiguous as to whether the content is licensed as open.

- Green open access – the final way – happens when the article has been placed in an open repository.

There are sometimes additional colors thrown into this rainbow, including platinum (meaning the journal is open but the author does not have to submit article processing fees), and black (where otherwise paywall-blocked articles are harvested from publishers and made available in less-than-legal ways). Our dashboard includes a few shades of gray, indicating articles we know are closed, invalid, or unknown. Closed refers to journal articles that are behind paywalls that you or your library pay for, while the latter two are small, but important sets that help us monitor our data health.

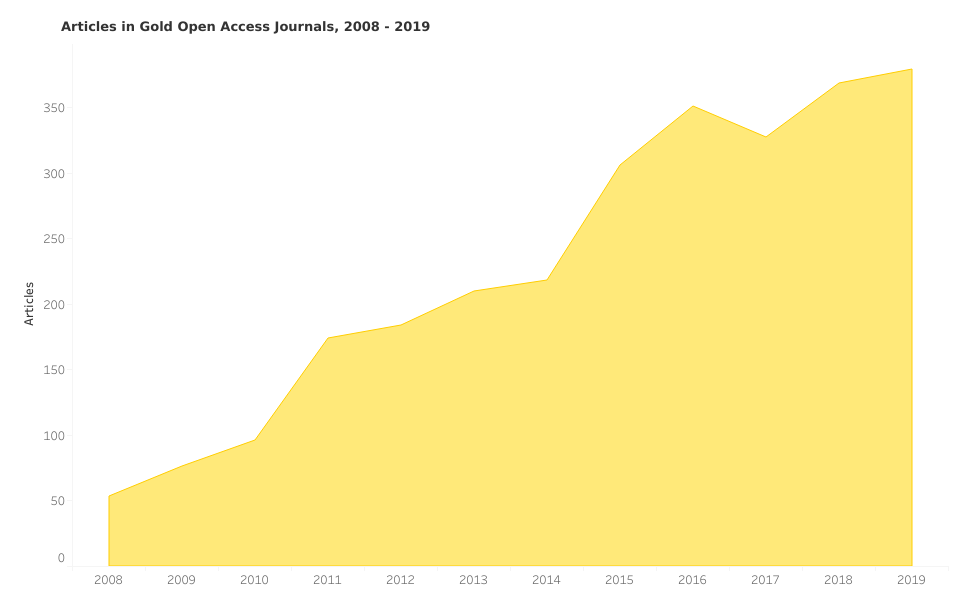

Further Explore Open AccessWhile open access is a global movement, it starts at the local level. We are taking advantage of advancements in the scholarly information infrastructure to enrich our data about what is being published by Smithsonian authors. This helps put us in a unique position to take the pulse on open access scholarship at the Smithsonian. This analysis reveals that a sizable portion of research produced by the Smithsonian is open access, and that this has been increasing as a proportion of all journal articles (though we will give 2020 a big asterisk, given COVID, and that the year is not yet complete).

Smithsonian-authored articles in gold open access journals from 2008-2019

Smithsonian-authored articles in gold open access journals from 2008-2019

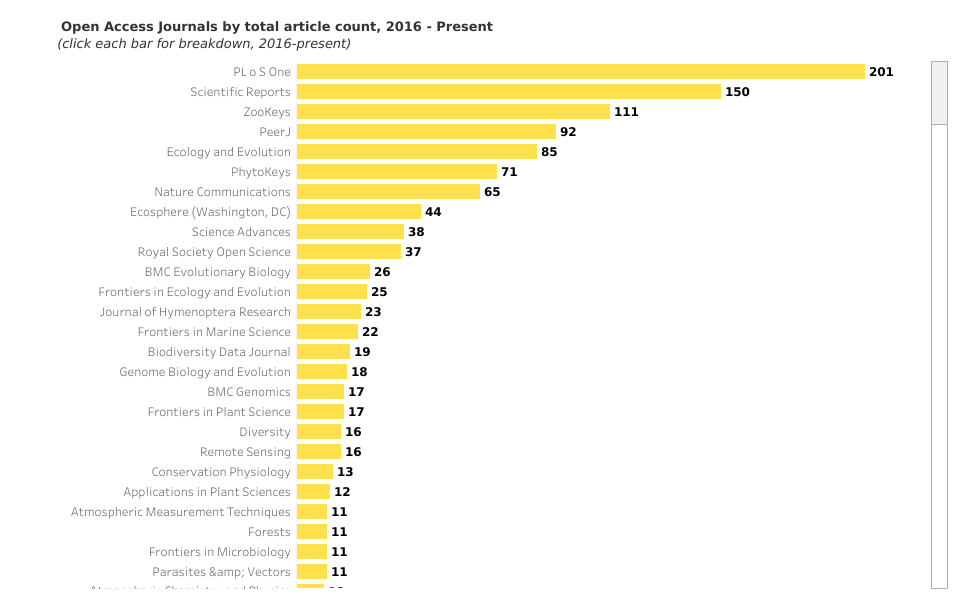

The top open access journals section shows which gold open access journals have the most Smithsonian articles, although drilling down to individual journals often shows a trend downward for many. This could indicate a growing list of gold journal options as the number of gold open access journals increase, or some other trend entirely.

Count of Smithsonian-authored articles by journal, for open access journals 2016-present

Count of Smithsonian-authored articles by journal, for open access journals 2016-present

There is plenty more to explore, including putting this dashboard in context with the broader scholarly community. Are the trends we see at the Smithsonian reflected in other scholarly institutions? What further connections or insights do you see from our dashboard? Leave your comments, suggestions, and questions in the comments.

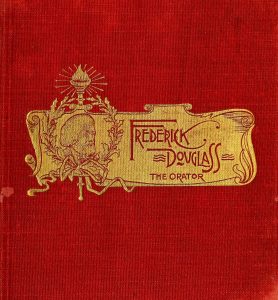

Introducing “Women in America: Extra and Ordinary”

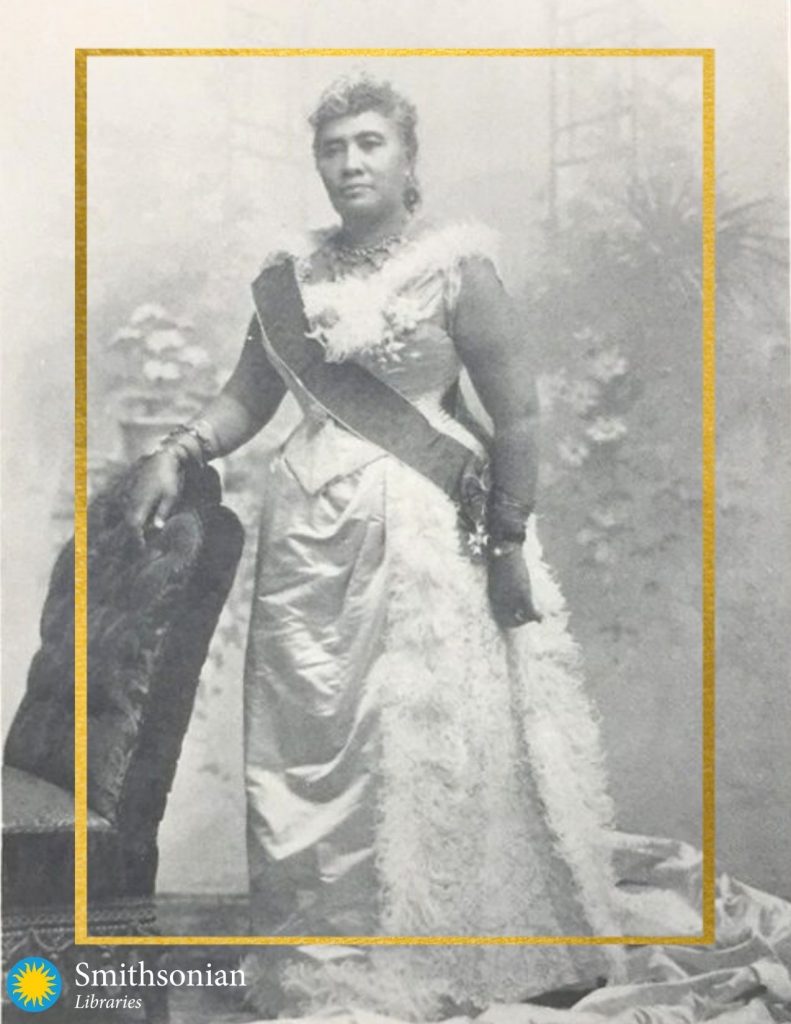

The stories of our past are powerful tools. They can be reminders of our successes and cautions of our failures. Entirely too often history has been written by and for the praise of white men, marginalizing women and people of color. Women in America: Extra and Ordinary is a collection of twenty-four women who lived from 1785-2013 in America. Some of their stories are extraordinary while others celebrate the strength of the everyday. Each aspect of representation is critical to show a comprehensive thread of real women in our past who were treated as extras in America’s story.

The digital content in Women in America: Extra and Ordinary is written for a middle school audience with common core standards for grades 6-8. It highlights twenty-four women represented in the Libraries‘ collections, with attention to diverse time periods, backgrounds, and contributions to America’s history. In addition to books, their stories are told through songs and objects from across the Smithsonian. The intention of this resource is to bring to light people who you may not have heard of and share aspects of their ordinary life as well as what made them extraordinary.

Each collection is housed on Smithsonian’s Learning Lab. The Learning Lab is a free, interactive platform for discovering millions of authentic digital resources, creating content with online tools, and sharing in the Smithsonian’s expansive community of knowledge and learning.

In the Women in America collections you will find Elleanor Eldridge, a single, successful woman of color born in 1785, who owned land that was sold off without her consent. A savvy businesswoman not to be taken advantage of, she hired a literate woman to transcribe her memoir and through the sales of her book earned the money to buy back what was hers. (Learn more about Eldridge in a previous blog post.)

Graphic based on portrait of Eldridge in Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (1842).

Graphic based on portrait of Eldridge in Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (1842).

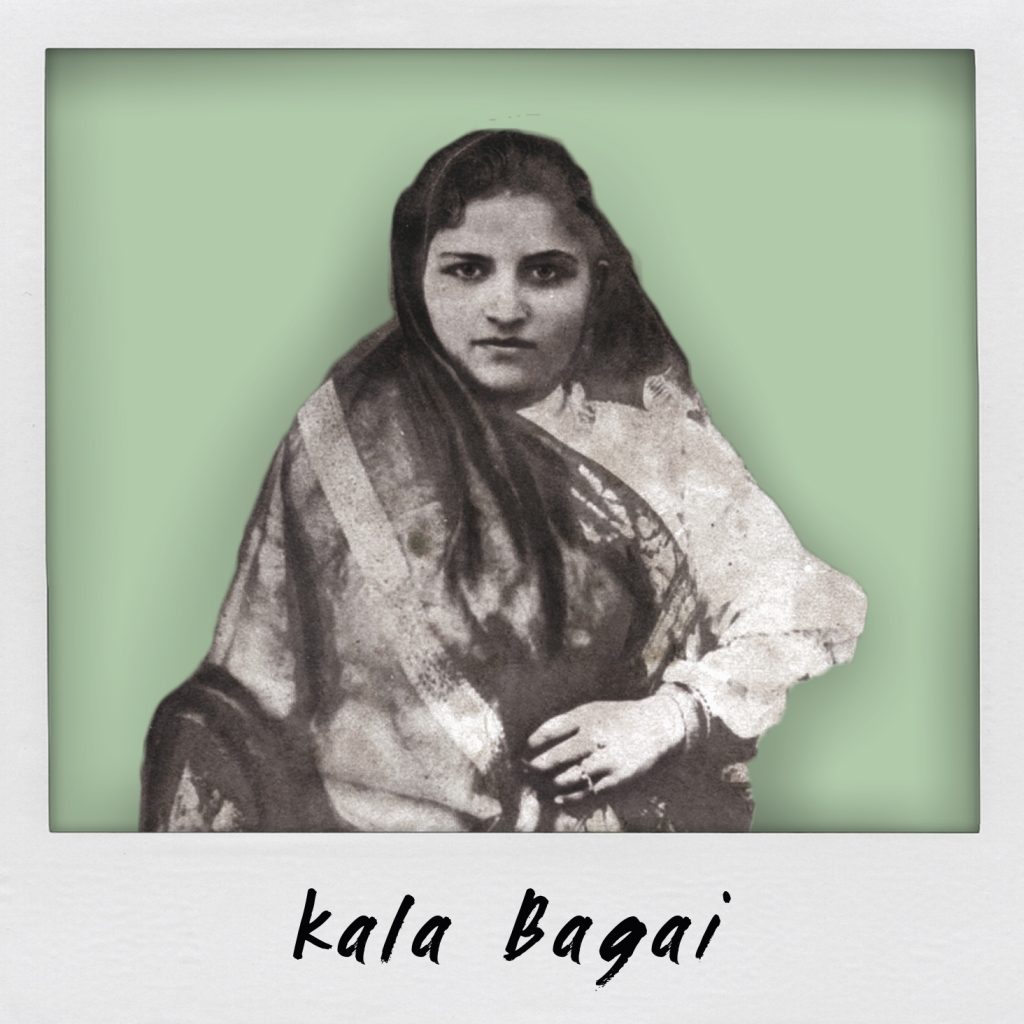

Or perhaps you will learn about Kala Bagai, born in 1892. Kala faced adversity as one of the first Hindu women to come to America. A few years after her citizenship was granted, it was taken away from her, her community, and other immigrants of color. She became a loving advocate for South Asian American’s rights and patiently fought for 23 years until citizenship was restored for all.

This image is adapted from adapted from a photo in 1985 Festival of American folklife. Image rights courtesy of Rani Bagai and the South Asian American Digital Archive.

This image is adapted from adapted from a photo in 1985 Festival of American folklife. Image rights courtesy of Rani Bagai and the South Asian American Digital Archive.

Or you may discover Anna Yousef Thomas, born in 1885. Anna and her family immigrated to America from Lebanon on the ill-fated Titanic. Knowing no English, the quick-witted Anna understood the ship was in trouble, despite what the crew was telling the passengers in the lower-class cabins. Swiftly, she secured a spot on a lifeboat for her and her children. Everyone else aboard from her village was lost.

This image is adapted from a photo in Telling Our Story: The Arab American National Museum (2007). Image rights courtesy of the Arab American National Museum Collection 2006.84.06.

This image is adapted from a photo in Telling Our Story: The Arab American National Museum (2007). Image rights courtesy of the Arab American National Museum Collection 2006.84.06.

All of these stories and more can be found at Women in America: Extra and Ordinary. We’re grateful for the support of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative for this project.

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles: Fall Edition

You asked and we delivered. A new set of digital jigsaw puzzles is finally here! We’re so glad you enjoyed our last round of puzzles and hope you find these equally entertaining.

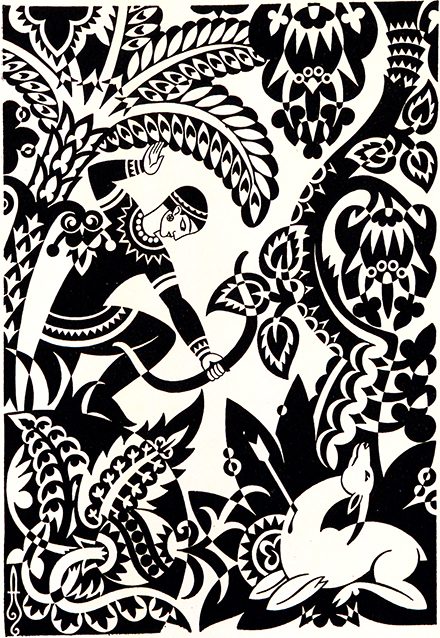

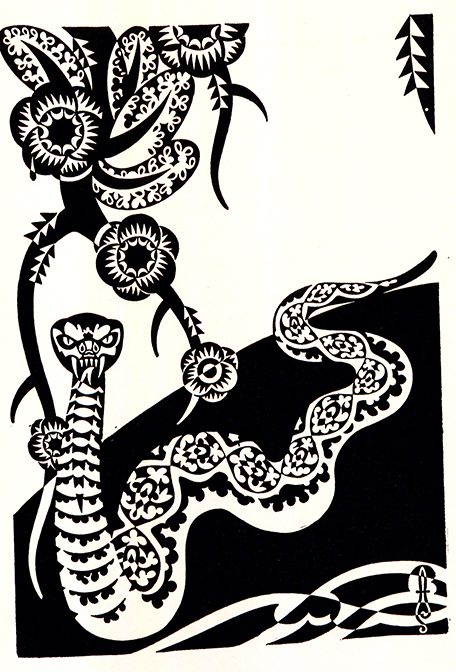

This time we’re featuring a few scenes that remind us of fall – from beautiful foliage to slightly creepy snakes and spiders. Play them right here on our blog or use the links to play full screen. Each puzzle is set at 60 pieces but they are customizable to any skill set. Click the grid icon in the center to adjust the number of pieces. As with our last set, all of the images are freely available in our Digital Library, Image Gallery or Biodiversity Heritage Library. Feel free to explore and make your own!

Front cover from Buist’s Garden Guide and Almanac (1896).

Born near Edinburgh, Scotland, Robert Buist trained at the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens before immigrating to the United States. After working in fine gardens and as a florist, he began a seed, nursery and greenhouse business called the Robert Buist Company. Buist was know for his roses and verbena and credited with introducing the poinsettia to the United States. He was the author of The American Flower-Garden Directory (1832); The Rose Manual (1844); and The Family Kitchen-Gardener (c1847).

Play online: https://jigex.com/EydZ

Front Cover, Buist’s Garden Guide and Almanac (1896) by Buist Seed Company.

Front Cover, Buist’s Garden Guide and Almanac (1896) by Buist Seed Company.

Jigsaw Puzzle

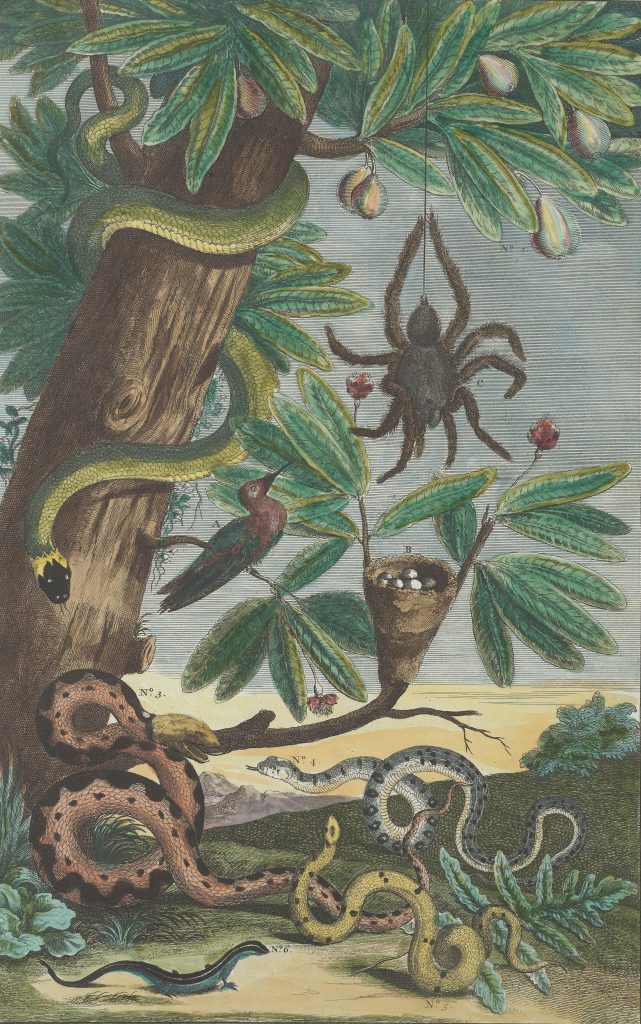

TAB. XLI from Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description (1734-1765) by Albertus Seba.

Snakes and spiders and birds, oh my! Dutch pharmacist Albertus Seba (1665–1736) devoted his life to collecting exotic plants and animals. His richly illustrated books document his cabinet of curiosities—a precursor of the modern museum. He commissioned hand-colored illustrations to document his extensive collection of plants, animals, and other curiosities, including a squid. His work served as a model for future books on collecting and classification, but it is also a landmark of artistry and design. This book is featured in our online exhibition Magnificent Obsessions: Why We Collect.

Play online: https://jigex.com/adsQ

TAB. XLI from Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description (1734-1765) by Albertus Seba.

TAB. XLI from Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description (1734-1765) by Albertus Seba.

Jigsaw Puzzle

“Crab Apples” by Louise Blakeney in Keramic Studio, (1903).

Adelaide Alsop-Robineau began the ceramic design journal Keramic studio in 1899. A self-taught artist, Alsop-Robineua ran the publication while maintaining a studio and teaching classes at Syracuse University. This particular illustration of crab apples is by Louise Blakeney and was featured in the October 1903 volume. Since Keramic Studio was an instructional publication, Blakeney includes instructions for painting the apples, specifying particular colors for the leaves and stems on page 133. Play online: https://jigex.com/s2TM “Crab Apples” by Louise Blakeney in Keramic Studio, October 1903.

“Crab Apples” by Louise Blakeney in Keramic Studio, October 1903.

Jigsaw Puzzle

“Wild Cat” by Wilhelm Kuhner in Animal Portraiture (1912) by Richard Lydekker.

Over the change of seasons already? We suspect this little wild cat is too. It’s one of fifty wonderfully expressive animals included in Richard Lydekker’s Animal Portraiture , available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Lydekker, a British naturalist, wrote the text for the book while leaving the imagery to German artist Wilhelm Kuhner.

Play online: https://jigex.com/shVx

“Wild Cat” by Wilhelm Kuhner in Animal Portraiture (1912) by Richard Lydekker.

“Wild Cat” by Wilhelm Kuhner in Animal Portraiture (1912) by Richard Lydekker.

Jigsaw Puzzle

Chrysanthemum pattern from Bijutsukai, Vol. 2 (1901).

Bijutsukai, a periodical published in Japan from 1896-1911, in sixty five volumes, intended to provide novel and exciting designs for textile artists, potters, and other craft makers; this was in response to domestic demand as well as increasing export needs. Each issue of Bijutsukai was wood-block printed in vibrant color on fine paper. Chrysanthemums, a favorite fall flower in the United States, are well represented as a design element — they’re the official flower of Japan.

Play online: https://jigex.com/SY2y

Chrysanthemum pattern from Bijutsukai, Vol. 2 (1901).

Chrysanthemum pattern from Bijutsukai, Vol. 2 (1901).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Pen, Paper, and Mail: Shopping and Corresponding

Today, most people are familiar with online shopping but some might also remember mail ordering. While one method uses computers, the other relies on paper. However, there are similarities. Both allow consumers to shop from the comforts of home, and both require mailing and shipping at some point. Then, items are delivered direct to the customer’s door. The Trade Literature Collection includes a variety of mail order catalogs. Let’s take a look at one from 1907.

This trade catalog is titled Catalogue No. 101 by Herr, Thomas & Co. (1907). On the first page, the company is described as a “Manufacturing Mail Order House” that sold directly to customers at factory prices. The catalog illustrates all kinds of products. It includes everything from furniture and home furnishings to jewelry and clothing. There is even a section on grocery and pharmaceutical items. Many of the products sound similar to what today’s online shoppers might order.

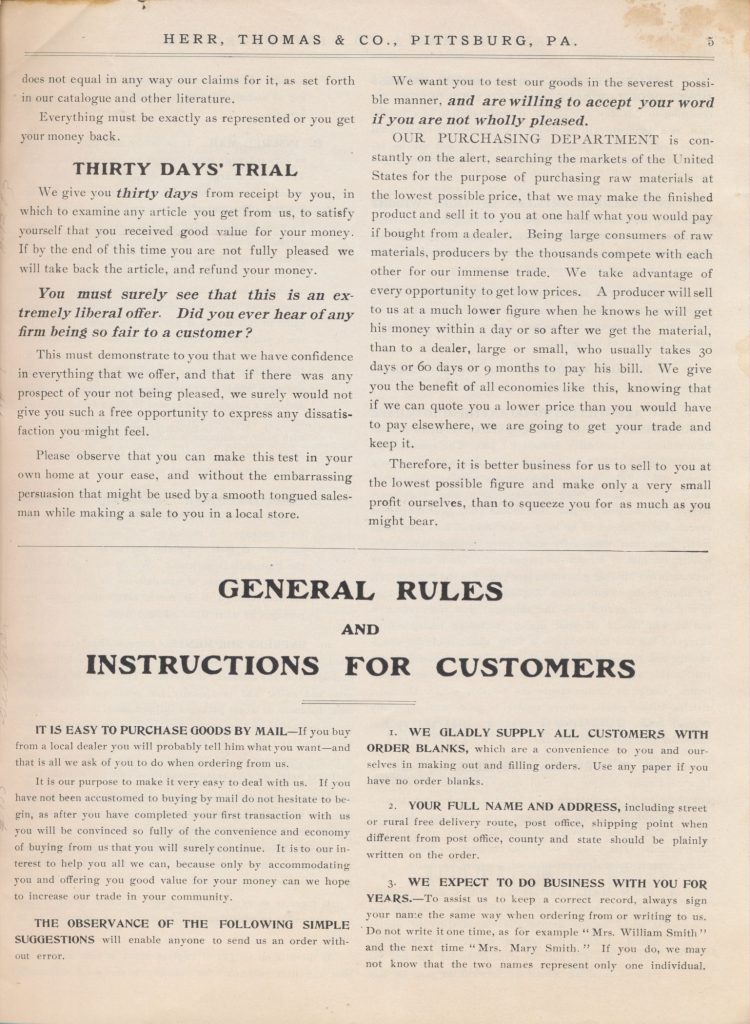

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Mail ordering was meant to be as easy as possible. That is how Herr, Thomas & Co. explained it in the “General Rules and Instructions for Customers” section. The customer was asked to simply mail a completed order blank, or form, with payment. Besides noting the specific items being ordered along with related information such as quantity, design, etc., it was important to include the Catalog Number on the order blank as well. If an order blank was not handy, any blank paper was acceptable as long as all necessary information was provided. For the convenience of customers, the catalog included delivery options and a table of freight and express rates based on location.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Mail ordering was meant to be as easy as possible. That is how Herr, Thomas & Co. explained it in the “General Rules and Instructions for Customers” section. The customer was asked to simply mail a completed order blank, or form, with payment. Besides noting the specific items being ordered along with related information such as quantity, design, etc., it was important to include the Catalog Number on the order blank as well. If an order blank was not handy, any blank paper was acceptable as long as all necessary information was provided. For the convenience of customers, the catalog included delivery options and a table of freight and express rates based on location.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 5, Thirty Days’ Trial and General Rules and Instructions for Customers.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 5, Thirty Days’ Trial and General Rules and Instructions for Customers.

In the early 20th Century, a common form of communication was writing letters. Perhaps, someone in 1907 might have ordered a desk, like the Combination Bookcase and Desk illustrated below (middle right). This bookcase/desk included space to store all the necessary writing supplies at an arm’s reach. It even came with a mirror. Directly below the mirror was a pull-out writing desk with a writing space measuring 18 inches by 25 inches. Pigeon holes provided spots for storing stationery and other writing supplies. The illustration below shows the writing desk in the closed position with embossed decoration on its lid, or closed door. A drawer and cupboard were positioned directly below the writing desk, and additional storage was provided on the five-shelf bookcase to the left. The heart in the cornice added a decorative and welcoming touch.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 27, Desk, Library Bookcase, Combination Bookcase, Combination Bookcase and Desk, Parlor Cabinet, Boudoir Desk, and Desk Set.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 27, Desk, Library Bookcase, Combination Bookcase, Combination Bookcase and Desk, Parlor Cabinet, Boudoir Desk, and Desk Set.

Writing requires more than a desk or quiet spot to compose a letter. Herr, Thomas & Co. also sold writing accessories, such as the Desk Set, shown above (bottom left). As might be expected, it included storage space for ink and pen. Two crystal glass ink wells accompanied the pen rest. A handy addition was the perpetual calendar so the letter writer never had to guess the date.

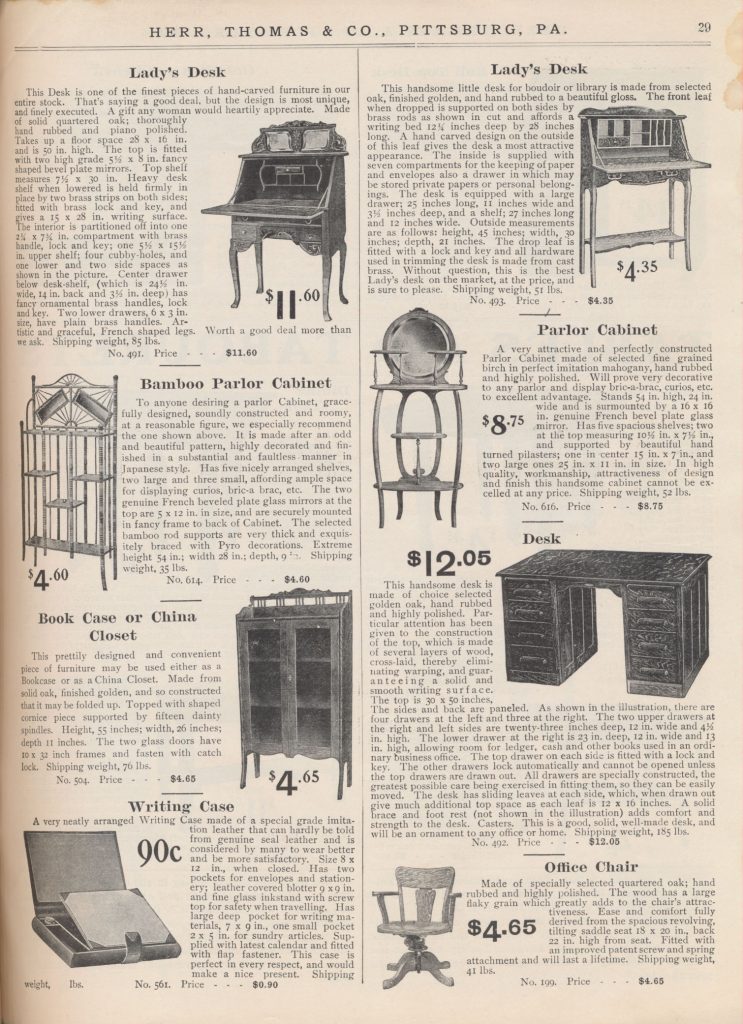

A writing case might also have been useful. This particular writing case below (bottom left) featured a large deep pocket to store writing materials in addition to a small pocket for miscellaneous items. Two other pockets provided space for stationery and envelopes. It came with a leather blotter, a glass inkstand with screw top, and a current calendar. When closed, the case measured eight inches by twelve inches and might have been a nice travel companion to keep in touch with family and friends back home.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 29, Lady’s Desk, Bamboo Parlor Cabinet, Parlor Cabinet, Book Case or China Closet, Writing Case, Desk, and Office Chair.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 29, Lady’s Desk, Bamboo Parlor Cabinet, Parlor Cabinet, Book Case or China Closet, Writing Case, Desk, and Office Chair.

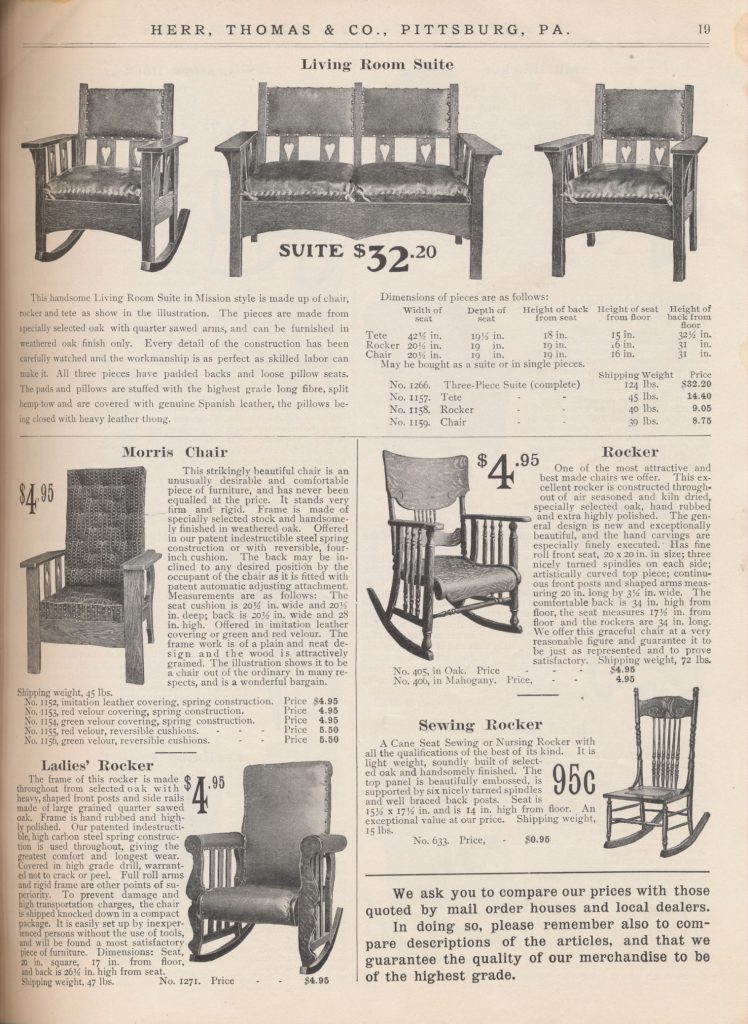

Besides desks, other types of furniture are also illustrated. The page below shows furniture suitable for a living room. Perhaps, the recipient of a letter caught up on news from a friend while reading correspondence and relaxing on a chair from the Living Room Suite. The three-piece Living Room Suite consisted of a rocker, tete, and chair. These pieces were Mission Style and made of oak. Each piece featured padded backs and loose pillow seats covered in leather. The hearts decorating the backs of the furniture seem to unify the set. The Living Room Suite was available as an entire set or individually.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 19, three-piece Living Room Suite (Rocker, Tete, Chair), Morris Chair, Rocker, Ladies’ Rocker, and Sewing Rocker.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101, 1907, page 19, three-piece Living Room Suite (Rocker, Tete, Chair), Morris Chair, Rocker, Ladies’ Rocker, and Sewing Rocker.

Whether someone in 1907 was ordering furniture, writing supplies, or even food and groceries, Herr, Thomas & Co. provided the option of shopping from home with their mail order catalog. Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in more mail order catalogs from the past? Take a look at these posts about John Wanamaker’s Spring & Summer 1915 catalog and Fall & Winter 1915-16 catalog.

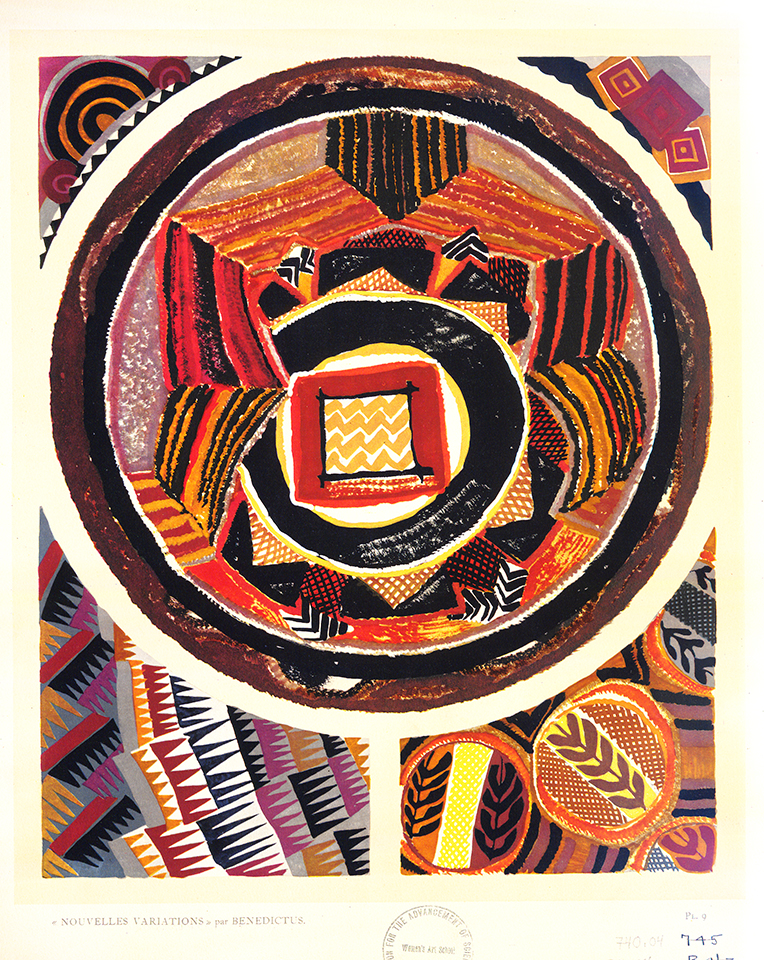

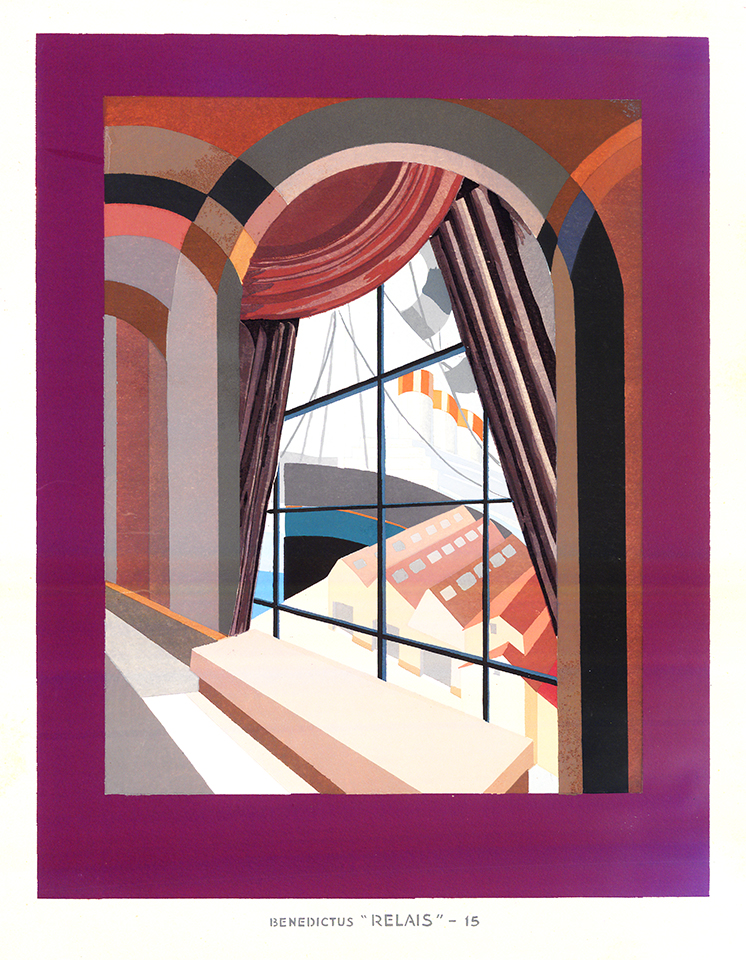

Art Deco: Picture Collections at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library

This is the seventh and final post in a series about the Art Deco resources at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum library. Each post will highlight primary resources which contain the styles and designs of the Art Deco era. These resources are divided into seven categories- world’s fair publications, interior and architecture books, trade catalogs, graphic design, pattern books, and picture files. This guide is not an exhaustive summary and these featured resources are just a portion of what awaits Art Deco enthusiasts and researchers in the Cooper Hewitt library collection. We are grateful to Jacqueline Vossler and Joseph Lundy for their generous support of this project.

Our branch at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library is currently closed to visitors as of September 30, 2020. But even when geography or other limitations keep you from visiting, you can still access plenty of exciting Art Deco resources from the comfort of your own home.

Through the Smithsonian Libraries’ Image Gallery, the Cooper Hewitt Library offers access to two great Art Deco collections: Edward F. Caldwell & Co’s lighting collection and the Thérèse Bonney Photography collection. While these online collections are not exhaustive they do give a good idea of what the library has and offer ample opportunity for non-local researchers.

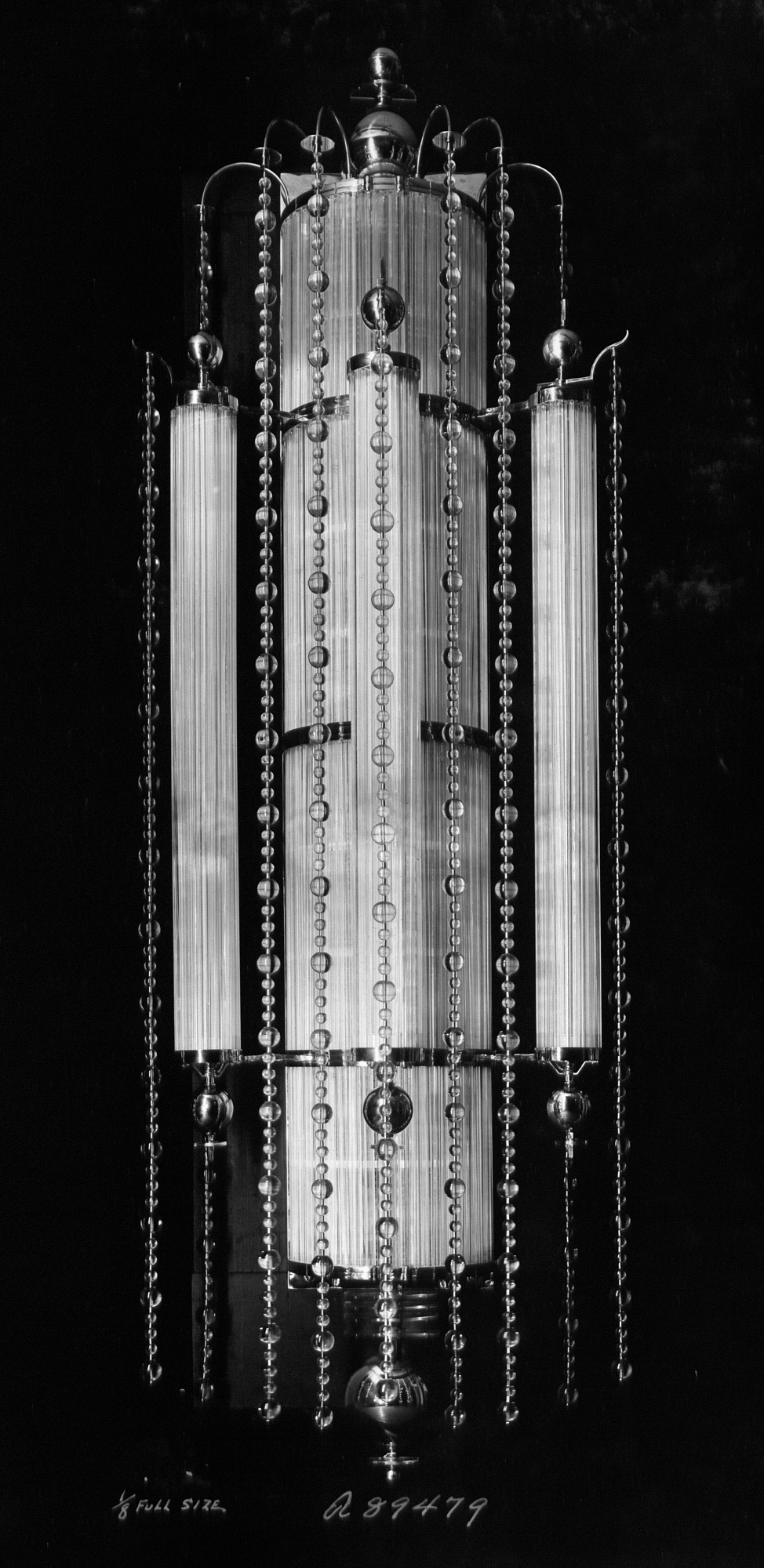

Edward F. Caldwell & Co., of New York City, was the premier designer and manufacturer of electric light fixtures and decorative metalwork from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. Founded in 1895 by Edward F. Caldwell (1851-1914) and Victor F. von Lossberg (1853-1942), the firm’s design legacy includes custom made metal gates, lanterns, chandeliers, ceiling and wall fixtures, floor and table lamps, and other decorative objects that can still be found today in many metropolitan area churches, public buildings, offices, clubs, and residences. A majority of these buildings were built in the early 20th century, a time of tremendous growth in construction and when many cities were being electrified for the first time.

Drawing A79216 in the E.F. Caldwell & Co. collection detailing a chandelier for Haddon Hall on the Upper West Side in New York in 1929.

Drawing A79216 in the E.F. Caldwell & Co. collection detailing a chandelier for Haddon Hall on the Upper West Side in New York in 1929.

The E. F. Caldwell & Co. Collection at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library contains more than 50,000 images consisting of approximately 37,000 black & white photographs and 13,000 original design drawings of lighting fixtures and other fine metal objects that the company produced from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. Learn more about the Caldwell & Company and search the digitized collection in Shedding Light on New York: Edward F. Caldwell & Co.

Photograph A89479 in the E.F. Caldwell & Co. collection featuring a light fixture for Radio City Music Hall.

Photograph A89479 in the E.F. Caldwell & Co. collection featuring a light fixture for Radio City Music Hall.

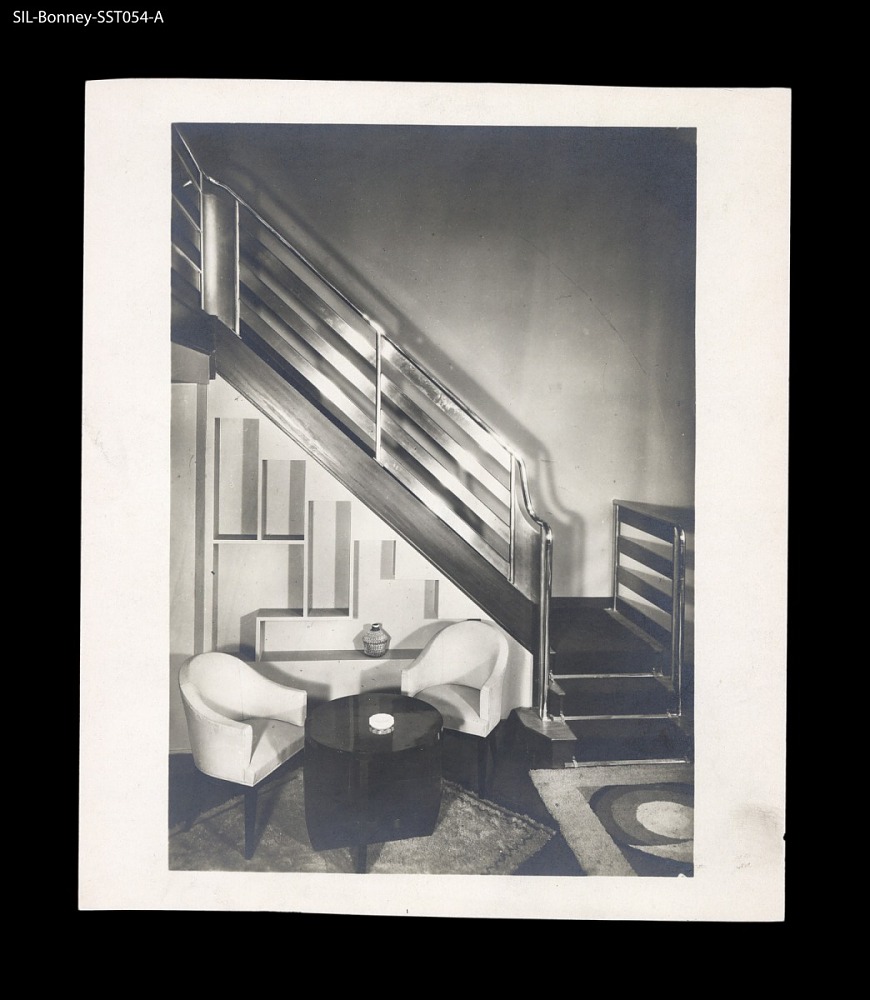

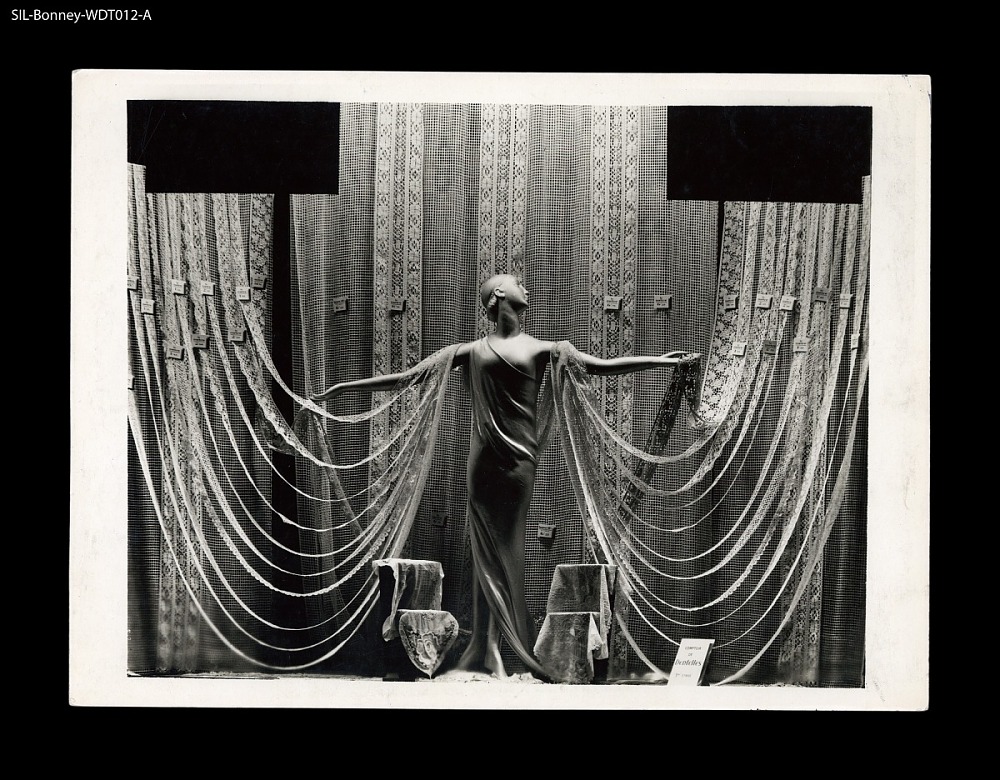

The Cooper-Hewitt Library’s collection of 4,000 Thérèse Bonney Photographs, 1925-1937 documents her personal observation of the life of Paris in the 1920s and 30s. The subjects of her photographs ranged from individual objects to interior settings to window displays to major building complexes and focused on the impact of modernism on European design. As seen here, some examples of the diversity of her interests include the interiors of the homes of artists and designers, department stores and other architecture.

Paris, France, ca. 1925. Polished steel banister. Jean Prouv (1902-84), designer/maker.

Paris, France, ca. 1925. Polished steel banister. Jean Prouv (1902-84), designer/maker.

Bonney captured images of decorative arts and architecture that are important visual documentation Art Deco in France as some of these subjects and structures no longer exist. Some examples of the diversity of her interests include the interiors of the homes of artists and designers, ceramics and glassware, barbershops, furniture, tapestry, lighting and gardens. Drawing from her life in Paris and experience with decorative arts she wrote Buying antique and modern furniture in Paris (1929) with her sister Louise. Later, Bonney’s WWII experiences and photographs were chronicled in Europe’s children, 1939 to 1943 (1943). Thérèse Bonney was a woman on the forefront of history — in design and life in Paris of the 20’s and 30’s, and later of the battlefields.

France, 1925-35. Window display of lace for the annual white sale, for Au Bon March.

France, 1925-35. Window display of lace for the annual white sale, for Au Bon March.

Additional information about the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library’s Thérèse Bonney collection can be found in these blog posts:

- Stairway to Modernism: Thérèse Bonney Collection

- Women’s History Month: An American in Paris Thérèse Bonney

- Shopping for Art Deco in an Art Deco Paris

- Thérèse Bonney: How to shop with Finesse

The Fix: Reusing Original Leather in a New Rebinding

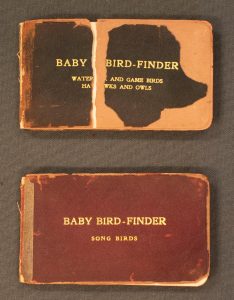

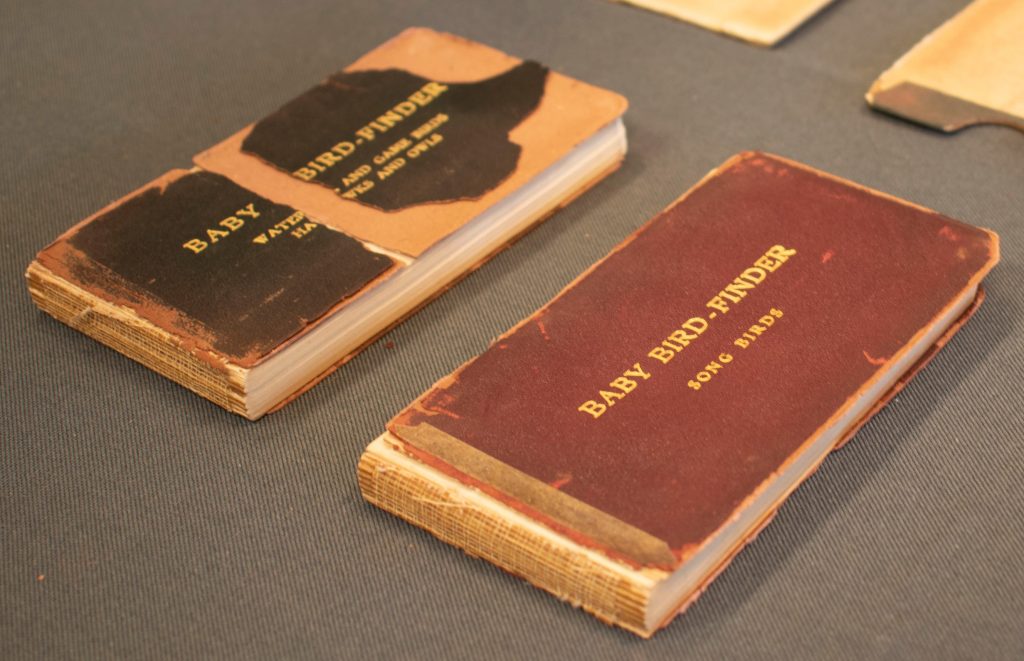

As with many of the books that come into our lab, the Baby Bird-Finder (1904-1906), a two-volume illustrated bird guide, was intended to be used. And used these volumes were, though not to find baby birds as the title suggests, but to identify bird species in New England and other Northeastern states. The “Baby” in the title refers to the diminutive, portable size of the volumes. Volume I covers song birds, such as flycatchers, larks and sparrows; volume II includes water and game birds, hawks, and owls. The volumes are illustrated, and include blank pages for birders to record their notes and observations. Both volumes are housed in our Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History and were adopted for conservation through our Adopt-a-Book program in 2017.

While the text blocks of this early 20th century set endured time and use relatively well, the bindings and box were in poor condition and required extensive treatment. The spines of both volumes were missing (Fig. 1), and as such the front covers were detached and in the case of the water and game birds volume, broken in two (Fig. 2). The original binding was made from thin acidic boards and the leather was similarly thin and brittle, thus requiring that the binding be completely replaced in order to give adequate protection to the text block and stabilize it for safe usage.

Fig. 1 Spines of both volumes missing.

Fig. 1 Spines of both volumes missing.

Fig. 2 Front covers broken and detached.

Fig. 2 Front covers broken and detached.

Once a treatment plan is decided upon, there is still the question of the extent to which the original binding materials can be integrated without compromising the book’s structure and usability. In the case of the Baby Bird-Finder set, while new bindings were essential, we made the decision to try to preserve the volume’s original appearance by incorporating the original leather from the front board, where the stamped title appears, onto the new binding. This posed a challenge: how to make the original leather and the new binding blend together seamlessly, while doing this in a way that protects the original leather.

After completely detaching the boards from the text block, I was relieved to be able to remove the fragile recto (front-facing) leather from the boards with relative ease. I prepared the text block for rebinding, and then was able to move onto the most exciting step in the treatment – creating a new binding that would integrate the original recto leather into the new binding.

Once the boards were measured and cut, I was able to begin the process of creating a depression for the original leather. First, I glued pieces of paper of the same thickness as the leather on top of the four boards (these being the front and back for each of the volumes). I then placed each of the two recto leather pieces on top of two of the boards and traced their outlines with a pencil. Using a sharp knife, I cut along the outline and peeled away the paper inside, making space to fit the original piece of leather into the board (Fig. 3 & 4).

Fig. 3 Recto leather and depression in the new front cover.

Fig. 3 Recto leather and depression in the new front cover.

Next we chose to use special aero linen cloth to cover the boards. The cloth was carefully toned with acrylic paint to match the color of the leather. This is part of the conservation work I particularly enjoy as it is an opportunity to play with colors and tackle the challenge of re-creating a specific shade.

I attached the new boards to the textblock and began the task of pasting the cloth onto the boards. It was particularly difficult to cover the recto boards in which the space for the leather had been carved out. What made it difficult was the fact that for pasting the cloth, I had to use a certain adhesive that dries fairly quickly, which meant that I had little time to make sure the cloth was rubbed well into all the little corners inside the carved-out spaces.I was grateful this step went without hiccups as there was little margin for error. Finally, I applied adhesive to the back of the original leather and carefully placed and rubbed the two delicate pieces into their respective carved out spaces (Fig. 5 & 6).

Fig. 5 Repaired cover of Song Birds volume of Baby Bird-Finder.

Fig. 5 Repaired cover of Song Birds volume of Baby Bird-Finder.

Now that the leather is level with the rest of the board it is hard to feel where the cloth meets the leather (Fig. 7 & 8). This is important both aesthetically, but also to minimize further damage to the leather through contact and abrasion.

Fig. 7 Original leather cover is level with new boards.

Fig. 7 Original leather cover is level with new boards.

Fig. 8 Original leather cover is level with new boards.

Fig. 8 Original leather cover is level with new boards.

Now both volumes of Baby Bird-Finder are conserved in a manner that is as close to the original as possible, and safe for use and study. Baby Bird-Finder has also been fully digitized and is available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

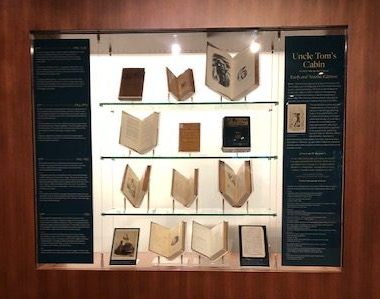

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Early and Notable Editions

I wrote what I did because as a woman, as a mother, I was oppressed and broken-hearted with the sorrows and injustice I saw, because as a Christian I felt the dishonor to Christianity – because as a lover of my country, I trembled at the coming day of wrath.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1853

in a letter to Lord Thomas Denman of London, England.

There are varying opinions about the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, yet it is inarguably one of the most influential books in American history. Written by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811 – 1896) to inform readers of the appalling realities of American slavery, it was first published in March 1852. The novel quickly became an international bestseller, second only in sales at that time to the Bible.

So goes the beginning of the introductory text for the current National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) Library exhibition, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Early and Notable Editions. The exhibition – which features editions not only from the NMAAHC Library collection, but also from other Smithsonian Libraries’ collections at the National Museum of American History Library, the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library – was created to highlight the early and notable editions of the novel in our library collections, and to reveal its fascinating publishing history.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Early and Notable Editions

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Early and Notable Editions

In regards to this exhibition, I have termed “notable” as having distinguishable characteristics, such as particular illustrations, a foreword written by an important or historical figure, or simply the number of sales an edition might have garnered when first published. Becoming a collector’s item in recent years could also make an edition notable.

The idea for this exhibit came about in 2016, at a time when the NMAAHC Library was receiving world-wide attention immediately before and after the grand opening of the museum. As a result, the library was also receiving numerous unsolicited donations of books. At some point I realized the book we received more than any other was Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and that each time it was a different edition. Matter of fact, after receiving at least six donated copies, none were duplicate editions! A day or so later I was talking to one of the NMAAHC curators about it, and she said, “well, why not create an exhibit?”

A while later I began the research for the exhibition and I was amazed at not only the number of various editions published in a short period of time, but also at aspects of the book I didn’t truly know (but thought I did), such as the publishing history, the public response, the international attention, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s ongoing efforts to promote and defend the book, and the great cultural impact of it on American history – there’s even an unsubstantiated but often repeated story that Lincoln once referred to Harriet Beecher Stowe as the “little lady who wrote the book that started this great war.”

First published by the John P. Jewett & Company, the novel changed ownership among U.S. publishers at least four times before the copyright expired in 1893. Each publisher also attempted to capitalize on its popularity by publishing new and “special” editions, where new elements, illustrations, and commentary were added. As a result, the novel was a bestseller for well over 30 years after it was first published and since then has continued to inspire numerous other publications and works of art.

Some of the notable editions included in the exhibition:

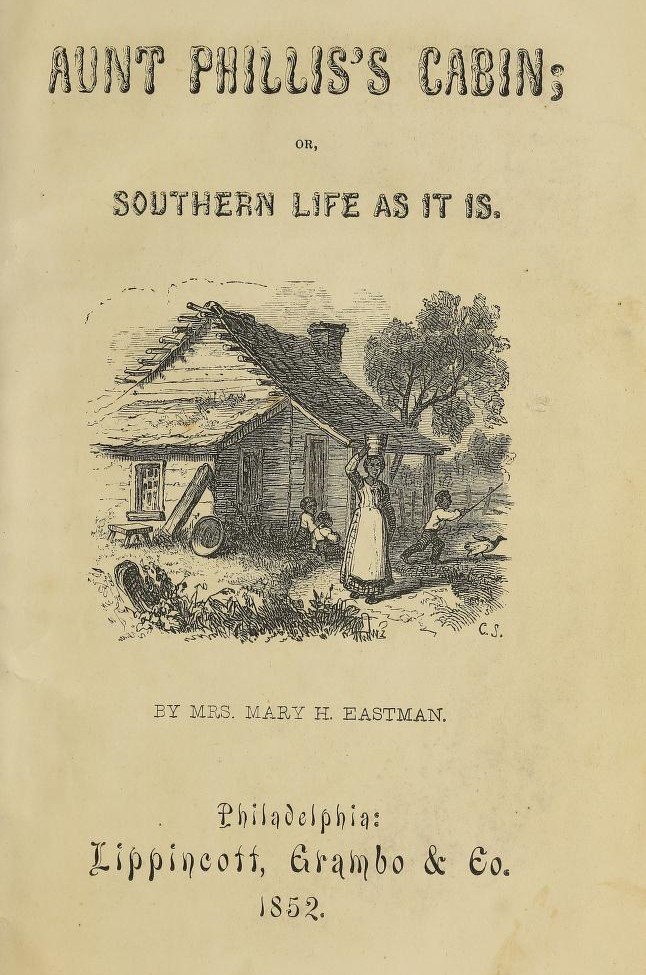

Title page from Aunt Phillis’s cabin

Title page from Aunt Phillis’s cabin

Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, or, Southern Life As It Is, by Mary H. Eastman

Lippincott, Grambo, 1852

In response to the initial publishing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a multitude of other novels were published to defend slavery and the southern image. These novels, which often painted a picture of slavery in opposition to Stowe’s (such as happy slaves who were well-taken care of), became known as the “anti-Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” or often shortened to the “anti-Toms.” Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, published just four months after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was one of the first such novels.

Arno Press, 1968 [Reprint of the 1854 edition published by John P. Jewett & Co., and Jewett, Proctor & Worthington]

Stowe’s critics harshly characterized her novel as propaganda with an inaccurate and unfair portrayal of slavery, and with characters who were not based on research or firsthand accounts. Stowe’s response to those critics, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, presents the facts and research behind the novel.

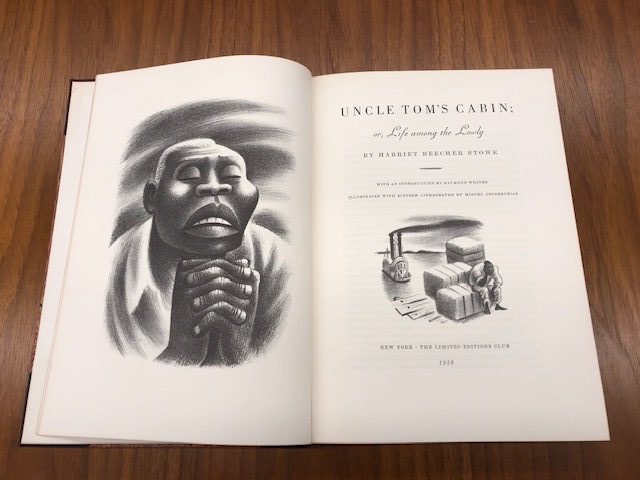

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly / Introduction by Raymond Weaver; illustrated with 16 lithographs by Miguel Covarrubias

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly / Introduction by Raymond Weaver; illustrated with 16 lithographs by Miguel Covarrubias

The Limited Editions Club, 1938

In its great publishing history, numerous versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin have included new illustrations, which is one of the things that might make a particular edition “notable.” Such is the case with this 20th century edition, richly illustrated with lithographs by Mexican American artist Miguel Covarrubias.

The museum is currently closed and expected to re-open on September 18th. Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Early and Notable Editions will not be on view during the museum’s initial re-opening, but we invite you to learn more through the NMAAHC Library webpage.The page includes a link to several editions of the novel featured in Smithsonian Libraries Digital Library Collections and to the exhibit bibliography. When we open our doors again, we hope you have an opportunity to see these notable editions in person.

Supporting Research: A COVID-19 Citation Database

Stephen H. Cox, branch librarian for the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park & Conservation Biology Institute, Mineral Sciences librarian at the National Museum of Natural History, and reference librarian at the National Museum of Natural History Library.

Stephen H. Cox, branch librarian for the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park & Conservation Biology Institute, Mineral Sciences librarian at the National Museum of Natural History, and reference librarian at the National Museum of Natural History Library.

My normal week is satisfyingly hectic: offering trainings to colleagues at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park (NZP), hopping on the Metro, providing reference support at the National Museum of Natural History’s (NMNH) main library, retrieving references for Mineral Sciences staff, and on Fridays, traveling 160 miles (round trip) to Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, VA. Add on committee meetings, literature searches, Association of Zoos & Aquarium bibliographies, and long-term projects, and it seems there is never enough time in a work week. And I love it.

Since being home, I have been just as busy, but in a much different way. I still meet with colleagues (virtually), provide reference support, and run literature searches, but I’ve also been able to complete my to-do list and make real progress on long-term projects. I was already an old hand at teleworking, which has served me well since mid-May, when I joined the Smithsonian’s COVID-19 Reopening Task Force (RTF) on the kind recommendation of an SI colleague.

But what does a zoo librarian know about public health? I’m glad you asked.

Before coming to the Smithsonian, I:

- taught scientific database research to undergraduate and graduate students

- Biology, Environmental Science, Kinesiology, Microbiology, and Zoology

- ran comprehensive literature reviews and occupational health systematic reviews while stationed at federal libraries

- sat ex officio on a university’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)

- created EndNote libraries with 50,000+ unique citations on subjects ranging from occupation lifting and pregnancy to the carcinogenic properties of asphalt sealant

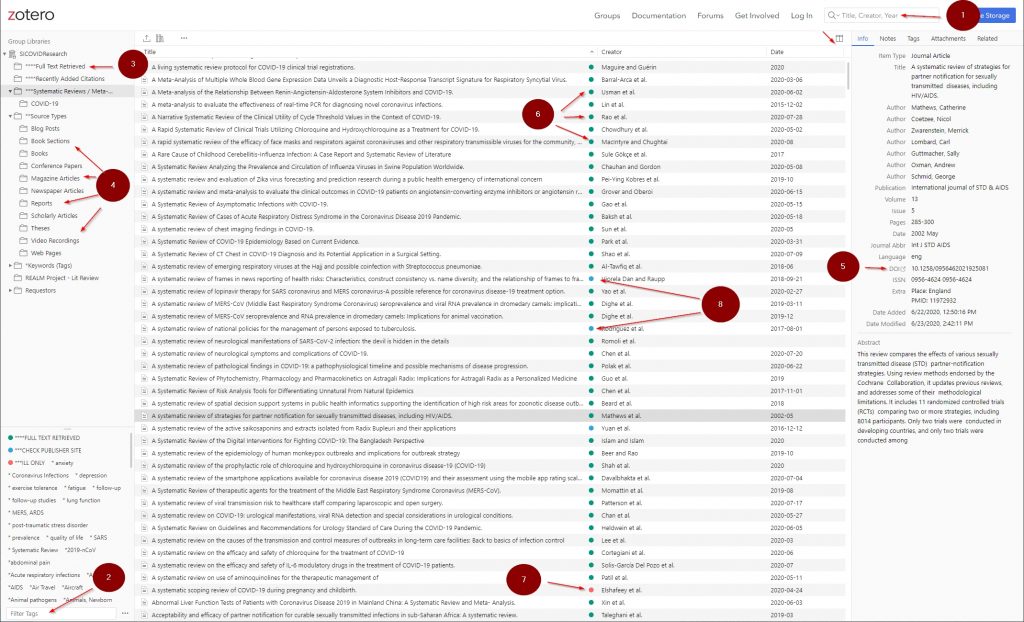

To assist the important work of my colleagues on the RTF, I did what I know best…created a citation database. I chose to build it in Zotero, an open source citation manager, which I extensively use to provide research support for SI colleagues and external organizations.

My goal for the COVID-19 citation database is simple: a one-stop repository of all SI accessible scholarly citations and curated (select) newspaper articles, video recordings, and websites. Reducing redundant efforts and increasing efficiency is the best way I know to provide support to my patrons, whether at NZP, NMNH, or SI in general.

Screenshot of Zotero. Click to enlarge.

Screenshot of Zotero. Click to enlarge.

- Main search box

- Tag search box

- Articles with full-text retrieved (SI staff only)

- Source Types

- Digital Object Identifiers (DOI) – permalinks to article full-text PDFs on publisher’s sites

- Articles that have had their full-text PDFs retrieved (SI staff only)

- Articles that require publisher site access for full-text retrieval (possible paywall)

- Articles that require interlibrary loan requests for full-text retrieval (SI staff only)

Methodology:

To create the baseline for literature, I utilized the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Browser, as well as the search string used by Battelle for the OCLC/Institute of Museum and Library Services Reopening Archives, Libraries and Museums (OCLC/IMLS REALM) literature review, and created the following search string:

(“COVID-19” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR coronavir* OR hcov)

I did not use any other search terms, in order to retrieve the maximum number of potentially relevant citations.

I retrieved results in Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, Elsevier’s Scopus, and Google Scholar. To identify burgeoning research, business reactions, and government assessments, I created a Google News Alert.

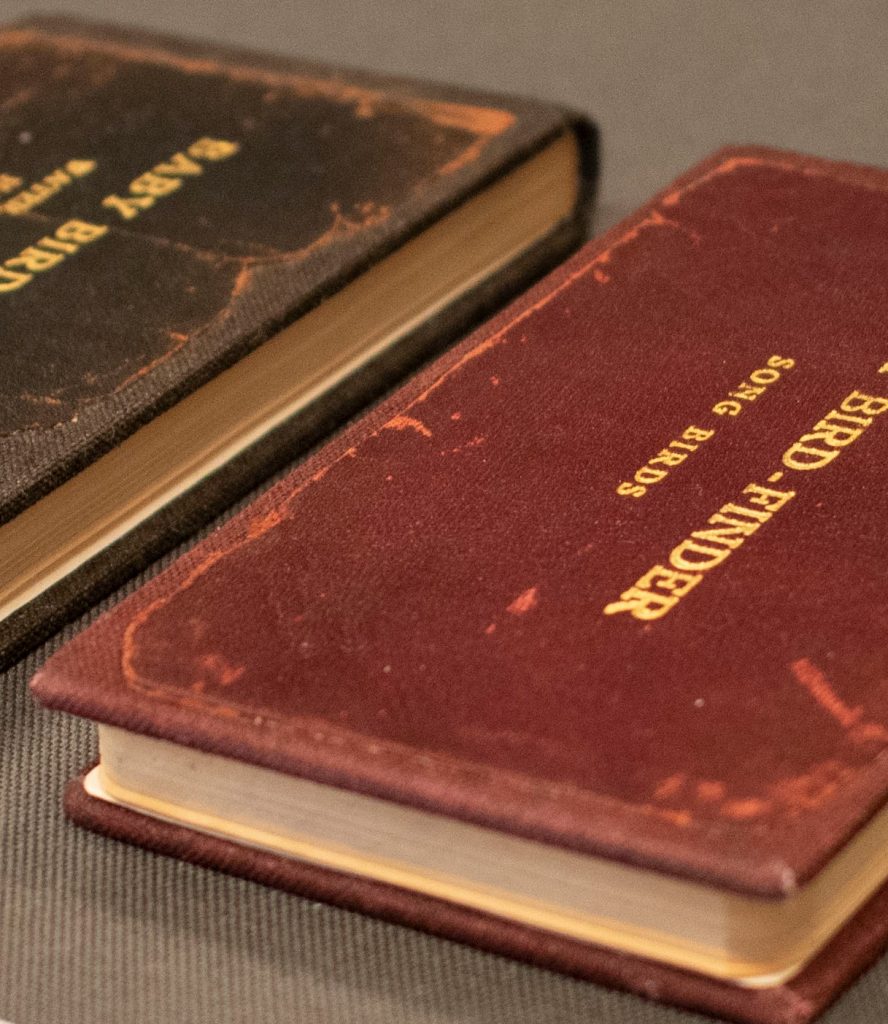

Maintenance:

Citation databases do not always export full records (even if the option is selected). In order to create complete records, I deduplicated nearly 40,000 results, making sure that (when possible) each citation had at least a title, author(s), date of publication, publication title, volume, issue, pages, and an abstract. Since COVID-19 literature has almost totally been written in 2020, most citations include DOIs. Additionally, many citations appear in databases during the pre-print stage, meaning they are often incomplete, so it is important to deduplicate/merge across multiple databases to create complete references.

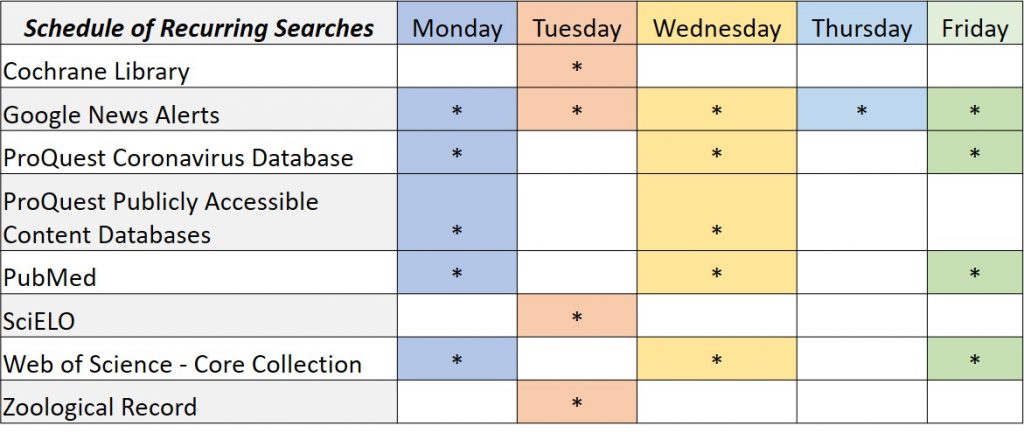

A database of this size requires a lot of discipline and can take over one’s life. I have created schedules for recurring searches (1) and maintenance (2) so I can have time to respond to patron requests.

Schedule of Recurring Searches

Schedule of Recurring Searches

I have since added more sources, and in addition to the aforementioned databases, I also run recurring searches in Cochrane Library, ProQuest Coronavirus Database and Publicly Available Content Databases, SciELO, and Zoological Record.

To date, I have reviewed 167,250 citations, adding an average of 950 new citations per day.

Use:

The online version of the Zotero database has two search boxes (including the ability to search just the tags). Since the online version does not reflect saved search folders created in the desktop version, I have created numerous keyword folders and manually update them every few days. Examples of delimiters include Source Types, Locations, Pathology, and Cleaning.

Users are able to highlight specific articles or even an entire folder and export the results as a bibliography with abstracts, making skimming to locate relevant sources much easier (CTRL-F is your friend).

Points of Interest:

I run searches every business day and base the frequency of searching on the refresh rate of a database (PubMed is run daily; ProQuest is run every few days). Each database has limits on the number of citations that can be exported (e.g., Web of Science – 500 at a time) or per day (ProQuest – 10,000). ProQuest includes keywords as notes, so I have set up automated searches so I can quickly find and delete these data hogs (that, coincidentally, just mirror information in the citation proper).

Print journalism is added regardless of the author’s perceived or overt bias. Once the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, I hope the database will serve SI’s historians well.

Going Live:

Since the database’s initial release , I have used it to create reports on mask and social distancing compliance for the NZP and the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center; face mask efficacy based on type (e.g., N95, KN95, cloth, etc.); air monitoring in office spaces; surface wipe sampling of different types of materials (e.g., steel, plastic, wood); temporal patterns in viral loads; and contact tracing.

Because COVID-19 research is relatively new, I also run pertinent searches on ancillary topics as they pertain to previous outbreaks (e.g., sanitization of surfaces for the elimination of viruses).

I have also created derivative databases for other groups. Currently, I’m providing reference and citation database training and support to the SI group tasked with creating risk assessment models.

If scientia potentia est, then surely convenient access to orderly data is just as important. Supporting researchers is one of the things Smithsonian Libraries does best. If my efforts make the work of my SI colleagues any easier, I’ve done my job.

The Library of Our Predecessors

What library equipment and supplies did our predecessors use? Some things have changed quite a lot while others remain somewhat similar. Let’s take a look at libraries from the past via this 1899 trade catalog.

The catalog is titled Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899) by Library Bureau. Consisting of 171 pages, it includes everything from library furniture and shelving to card catalogs and charging systems for borrowing books.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, front cover.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, front cover.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, title page.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, title page.

An essential piece of equipment in any library is the book truck or book cart. In this 1899 catalog, it was described as “one of the most useful devices ever made for an active library.” Although many more useful devices have since been invented, book carts still remain an important part of the library. The book truck shown below is 40 inches long, 40 inches high, and 14 inches wide. It had the capacity to hold six book shelves. This book truck was made of oak with rubber wheels, and the sides of the cart were padded with rubber for extra protection. Just like today, book carts gave staff the opportunity to sit at their desks and work with several shelves of books at one time.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, page 37, L. B. Book Truck.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, page 37, L. B. Book Truck.

The Hammond Card Cataloger was a special typewriter for libraries, especially useful for typing catalog cards, shelf lists, reports, correspondence, etc. An attachment to hold catalog and index cards was especially handy. Interchangeable type wheels to accommodate most languages were also available. Most importantly for libraries, there was a type wheel with the cataloging characters from the “Library school card catalog rules.”

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, page 158, Hammond Card Cataloger.

Library Bureau, Boston, MA. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau, 1899, page 158, Hammond Card Cataloger.