Libraries' Blog

Walcott’s Wild Flowers: An Interview with Pamela Henson

Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott features more than 250 exquisite reproductions of Walcott’s celebrated watercolors of wildflower life. Edited by Pamela Henson, this stunning volume is a collaboration between Prestel Publishing and the Smithsonian Institution. We invite you to hear personally from Pam in this interview.

L: How did you become interested in history and first start out in your career?

P: I love science and started out as a biology major, but I earned my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in American studies from The George Washington University in the early 1970s. The George Washington University had a cooperative program with the Smithsonian, a precursor to its museum studies program today. During my master’s program, a group of us were hired by the Smithsonian to do a visitor behavior study at the National Museum of Natural History. I was hired as an “intermittent” (no fixed hours), not even part-time, temporary, GS-3 psychology aide. I learned a lot about how the public interacts with our exhibits, what works, what does not work. I then heard about an entry-level position with a new Smithsonian oral history project created by Secretary S. Dillon Ripley. I had done oral history interviews as part of my master’s thesis and was hired as the assistant, advancing all the way up to a GS-5! The project moved to Smithsonian Institution Archives and the historian was leaving, so shortly after that, I advanced to the historian position, and received a Ph.D. in history and philosophy of science from the University of Maryland. I’ve been in this position ever since, and I’ve loved it!

Institutional Historian Pamela Henson.

Institutional Historian Pamela Henson.

Describe your current role at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

I am the Institutional Historian for the Smithsonian, in the Institutional History Division, Strategic Programs and Initiatives, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. I have several major functions. I provide background information on the history of the Institution to Smithsonian management, as well as scholars, the general public, and students. I also record oral history interviews with Smithsonian staff.

Smithsonian people often stay here a long time. The first interviewee was Charles G. Abbot who worked at the Smithsonian from 1895 to 1973 – 78 years! We record the lives of a wide array of our community, pivotal people like the security force, conservators, and educators. We are just about to launch a Smithsonian-wide project with interviews online, to gather the memories and reflections of the whole Smithsonian community at our 175th anniversary.

I also write, lecture, prepare exhibits, and do social media for both scholarly and popular audiences. I enjoy the variety of tasks I do, from interviewing an aeronautics curator, to preparing an exhibition on women at the Smithsonian, to helping set up a program on the history of information systems at the Institution. I’ve been at the Smithsonian since 1973, and I still get asked questions I don’t know the answer to.

Tell me about Wild Flowers of North America. How did you first get involved with this project?

My first office was in the Arts and Industries Building and it had two framed prints of wild flowers on the wall. I saw similar ones in the Smithsonian Castle when I moved to Smithsonian Institution Archives which was located there. I asked around and found out they were by Mary Vaux Walcott, wife of Smithsonian Secretary Charles Doolittle Walcott.

With my background in history of science and interest in the history of women in science, I’ve studied several Smithsonian women botanists, including Agnes Chase, a grass expert. I also studied the history of scientific illustration. Chase began as an illustrator. I’ve done exhibits and written on illustration that included both Chase and Walcott, but their styles were very different. Walcott’s were so beautiful – were they botanical art or scientific illustration? So I studied Walcott more. While her drawings were much more beautiful than Chase’s, they were very accurate, only contained the wild flower, not the surrounding environment. Her goal was to create drawings that introduced these flowers, many unknown, to the scientific world. So I concluded she was more a scientific illustrator than a botanical artist.

Why is the story of Mary Vaux Walcott important, and what about her life or work stands out to you the most? Did you uncover anything surprising in your research for the book?

Walcott is an example of how access to education for women was still limited, even after women’s colleges were established. Her work also shows how the field of botany was much more welcoming to 19th century women than other areas of natural history. It exemplifies the ways women were able to enter science “from the peripheries” such as art, as shown by scholars Margaret Rossiter and Sally G. Kohlstedt. She did not need to work, but had this incredible devotion to the task of creating visual images of and sharing all of these inaccessible wild flowers from remote sites in the Canadian Rockies.

I knew she married late in life, but I had not realized how strongly both families opposed the marriage.

I was very impressed with how fearless and resilient she was throughout her life. When she no longer had family to scale the high peaks of Canada with her, she went on her own or with other Quaker women. And she was not afraid to completely change her life at 55 by marrying Walcott and moving to Washington.

Mary Vaux Walcott with camera. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Mary Vaux Walcott with camera. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

What are your favorite illustrations from the book?

I have a fondness for the first two I found in my office, a magnolia and a balsamroot. I like the curious ones, like the skunk cabbage; the really delicate ones like the Alberta primrose; as well as the ones that have such exuberance in their short lives, such as the saltmarsh gentian. And the diversity, the variety of ways plants have evolved to survive in almost any environment.

Alberta Primrose from North American Wild Flowers (1929).

Alberta Primrose from North American Wild Flowers (1929).

What do you hope readers take away from Wild Flowers?

A greater appreciation of these plucky plants that exist briefly in very difficult environments and a concern that we don’t lose them to climate change. And an appreciation of a plucky women who found a way to make contributions to science even when she faced many obstacles.

Any final thoughts/observations?

It is always a fascinating journey to get to know another person’s life – how Walcott constructed it, the doors that were closed to her, the paths she followed. Her story provides many life lessons.

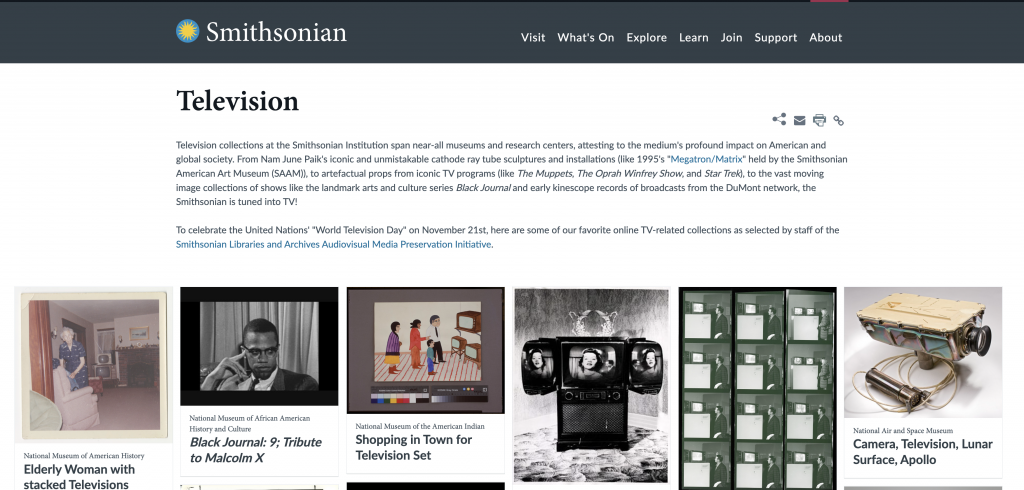

Tuning in for World Television Day

To celebrate November 21 as World Television Day, staff from the Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI) have aggregated 100 of their favorite online Smithsonian collection items about TV. Take a look at our Spotlight on Smithsonian television collections.

Screenshot of Smithsonian Spotlight on Television

Screenshot of Smithsonian Spotlight on Television

First designated by the United Nations General Assembly in 1996, World Television Day celebrates the technology as “a symbol for communication and globalization in the contemporary world.”

While our new Smithsonian Spotlight prominently features several moving image collections from TV history—episodes of Black Journal, a rare interview with Selena, and mealtime footage aboard Apollo 11—this online exhibition’s selections lean heavily on artefactual television legacies. That’s because so many of the Smithsonian’s rich television programming collections in the format of videotapes and kinescope films have yet to be digitized. The AVMPI is excited to dedicate its efforts in the upcoming fiscal year to changing this oversight.

Edward R. Murrow interviews Cab and ‘Nuffie’ Calloway on Person to Person in 1956. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Edward R. Murrow interviews Cab and ‘Nuffie’ Calloway on Person to Person in 1956. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Thanks to the generosity of the Smithsonian’s National Collections Program and the American Women’s History Initiative, the AVMPI is making television collections one of our project’s thematic foci for 2023. Television’s enormous impact traverses so many areas of American and global society that it makes TV an excellent lens through which we can look at social change, technological developments, and distinct cultures and traditions. In 2023, we will be digitizing and hope to make available the complete collection of 2-inch quadruplex videotapes of Hal and Halla Linker’s extensive travelogue television series, The Wild, the Weird, and the Wonderful, from the Human Studies Film Archive; we will create new scans of several episodes of the Edward R. Murrow-hosted Person to Person celebrity interview program broadcast on CBS in the 1950s and held by the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC); and, we will preserve all of the films and videos that form part of the Sally K. Ride collection at the National Air and Space Museum.

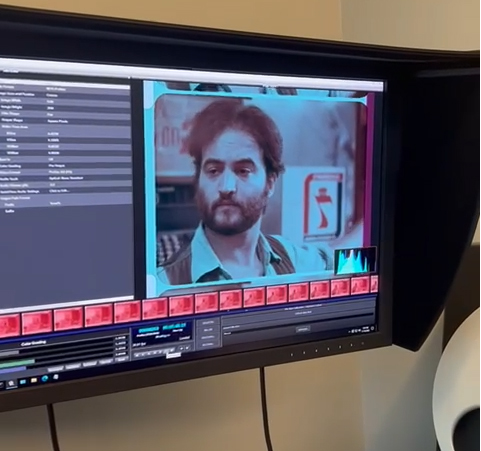

Last week, AVMPI Task Force members Bleakley McDowell (NMAAHC’s Senior Media Conservator) and Leigh Gialanella (National Museum of American History’s Digital Archivist), along with Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting, met at NMAAHC to scan several early 16mm kinescope TV recordings from the Allen Balcolm Du Mont collection and other works. These included a DuMont network commercial starring Norman Rockwell, which we hope to share with online audiences in the coming months, and a legendary but long-unseen Smithsonian exhibition film starring television comedy icons John Belushi and Gilda Radner.

Appearance by John Belushi in a Smithsonian exhibition film, ca. late-1970s. National Museum of American History, Archives Center.

Appearance by John Belushi in a Smithsonian exhibition film, ca. late-1970s. National Museum of American History, Archives Center.

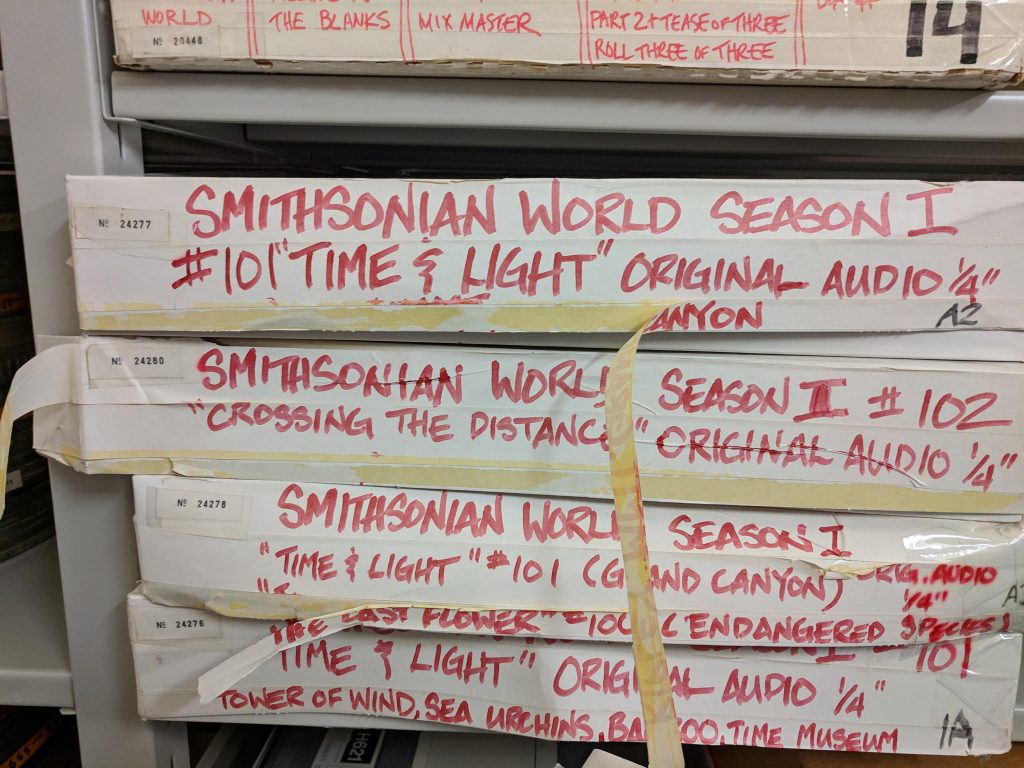

Our own Smithsonian Institution Archives also hold rich television collections as well, for which preservation and digitization is already underway. Thanks to the extraordinary work of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Media Digitization Manager Kira Sobers and Preservation Coordinator Alison Reppert Gerber, the first two seasons of the 1980s SI co-produced series, Smithsonian World, will become available online in 2023. Co-produced by public television affiliate WETA and hosted by historian David McCullough, Smithsonian World ran for six seasons from 1984 until 1989 and is but one of the Institution’s forays into broadcast television that the AVMPI hopes to unlock for online audiences in the coming year.

Stay tuned!

Welcoming audiences to our ‘World’. Materials for Smithsonian World in Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Welcoming audiences to our ‘World’. Materials for Smithsonian World in Smithsonian Institution Archives.

A Few Options for Cooking in the 1860s

With Thanksgiving just around the corner, we might be thinking of delicious food. Or perhaps we are realizing how much time it will take to prepare such a meal. Modern kitchen appliances have made cooking easier but imagine what it was like to cook on a stove, such as one of these, in the 1860s.

This trade catalog is titled Catalogue of Stoves (1866) by Potter, Paris & Co. The company was established in 1848 and manufactured stoves and related accessories.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), title page.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), title page.

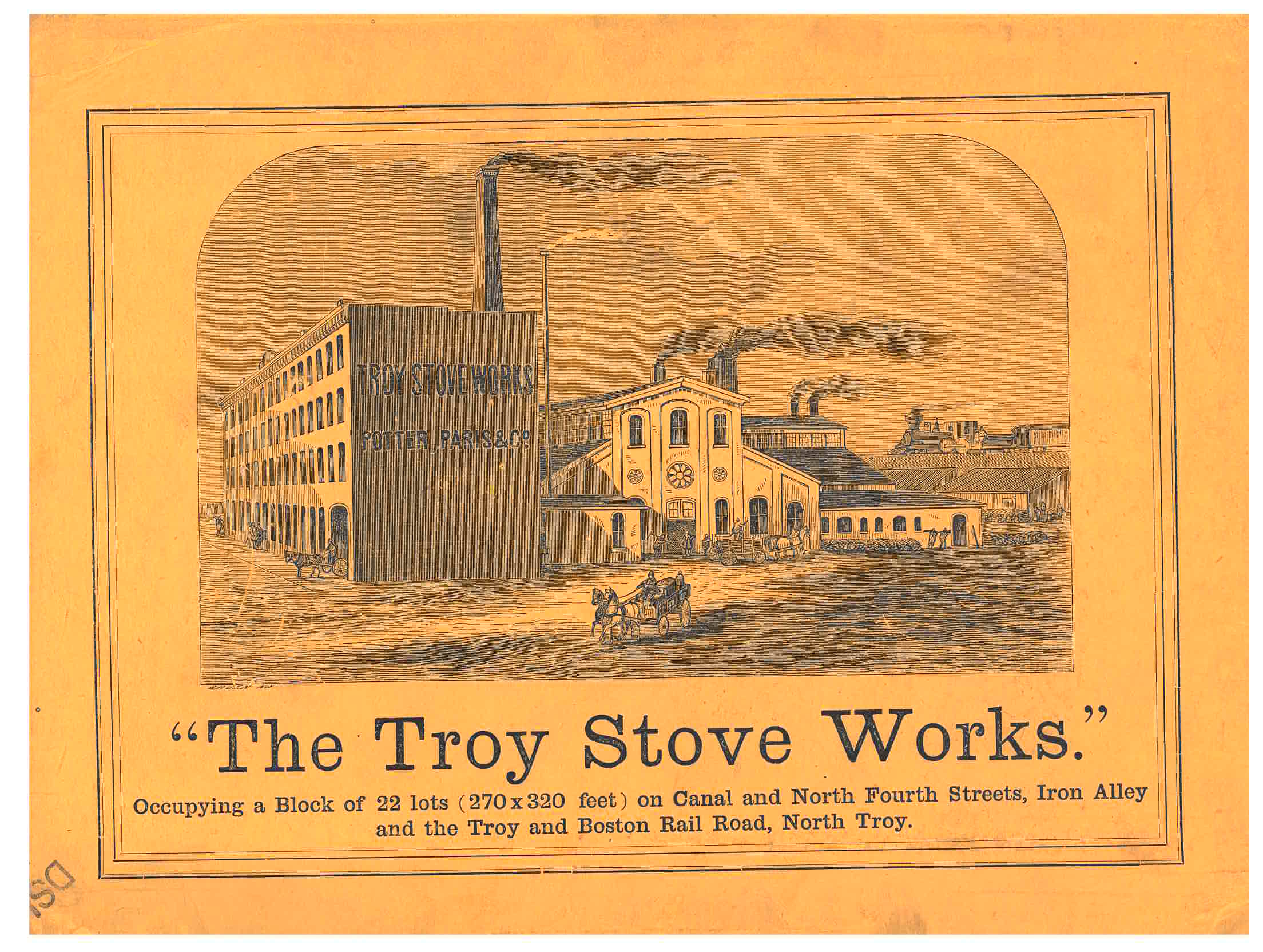

Just prior to the publication of this catalog, the company built a new foundry during the Summer and Fall of 1865. It was called the Troy Stove Works and occupied 22 lots in Troy, New York. It was there that Potter, Paris & Co. manufactured their stoves.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), back cover, Troy Stove Works in Troy, NY.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), back cover, Troy Stove Works in Troy, NY.

It appears that Potter, Paris & Co. intended for this catalog to cover two years, as an introductory page includes a statement dated July 1866 explaining that the catalog “will probably be for two years, 1866 and 1867.” It also mentions that “separate cuts of any new stoves” during that time will be provided to their customers for insertion or pasting into the catalog.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), unnumbered page [2], statement about terms and prices.As it turns out, the firm of Potter, Paris & Co. dissolved at the end of 1867. Burdett, Paris & Co. became the successor to Potter, Paris & Co. and continued manufacturing stoves at the Troy Stove Works. We learned that fact from another trade catalog titled Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868) by Burdett, Paris & Co. which was highlighted in a previous post.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), unnumbered page [2], statement about terms and prices.As it turns out, the firm of Potter, Paris & Co. dissolved at the end of 1867. Burdett, Paris & Co. became the successor to Potter, Paris & Co. and continued manufacturing stoves at the Troy Stove Works. We learned that fact from another trade catalog titled Illustrated Catalogue of Stoves & Hollow Ware (1868) by Burdett, Paris & Co. which was highlighted in a previous post.

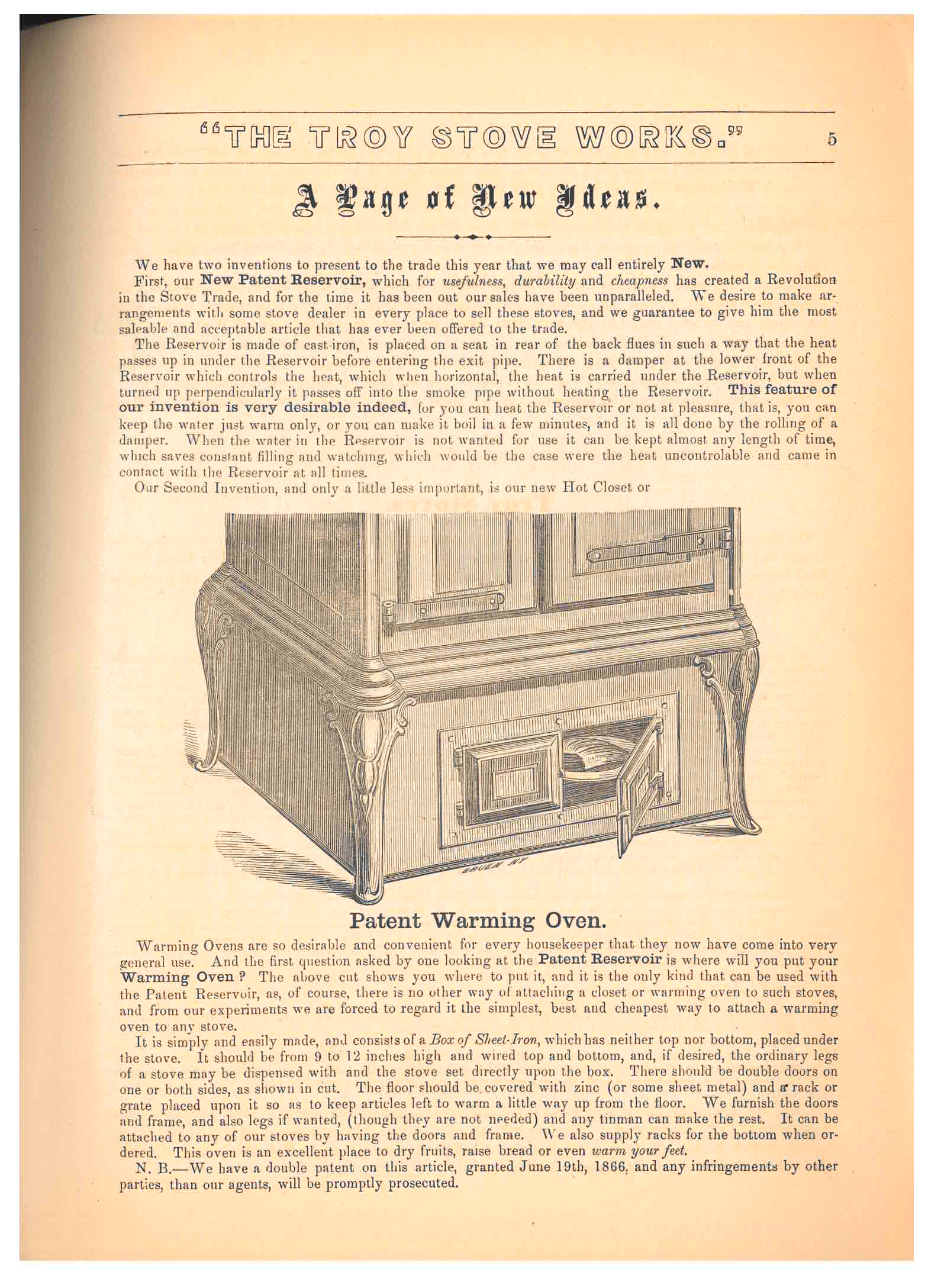

But now, let’s examine a few stoves manufactured by Potter, Paris & Co. around the year 1866. Turning to page 5 of Catalogue of Stoves (1866), we spot the heading, “A Page of New Ideas.” This is where Potter, Paris & Co. presented two new inventions, both available on their stoves. These two ideas were the “New Patent Reservoir” and the “Patent Warming Oven.”

The reservoir was made of cast iron with the option of being enameled or galvanized. Its position “on a seat in rear of the back flues” allowed heat to pass “up in under the Reservoir before entering the exit pipe.” A damper controlled heat in the stove. If the damper was placed in a horizontal position, the heat was carried under the reservoir. If the damper was moved to a perpendicular position, the heat passed through the smoke pipe without heating the reservoir. This provided the option of either heating or not heating the reservoir which meant water in the reservoir could be kept warm or boiled. The New Patent Reservoir is shown below on a stove called “Our Mutual Friend.”

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 7, “Our Mutual Friend” stove showing New Patent Reservoir.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 7, “Our Mutual Friend” stove showing New Patent Reservoir.

The other new idea was the Patent Warming Oven. Measuring 9 to 12 inches high, it was made of “a Box of Sheet-Iron, which has neither top nor bottom, placed under the stove.” The floor under the stove was covered with zinc or sheet metal, and a rack or grate was positioned to keep food being warmed off the floor. As shown in the illustration below, the warming oven included double doors.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 5, New Patent Reservoir and Patent Warming Oven.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 5, New Patent Reservoir and Patent Warming Oven.

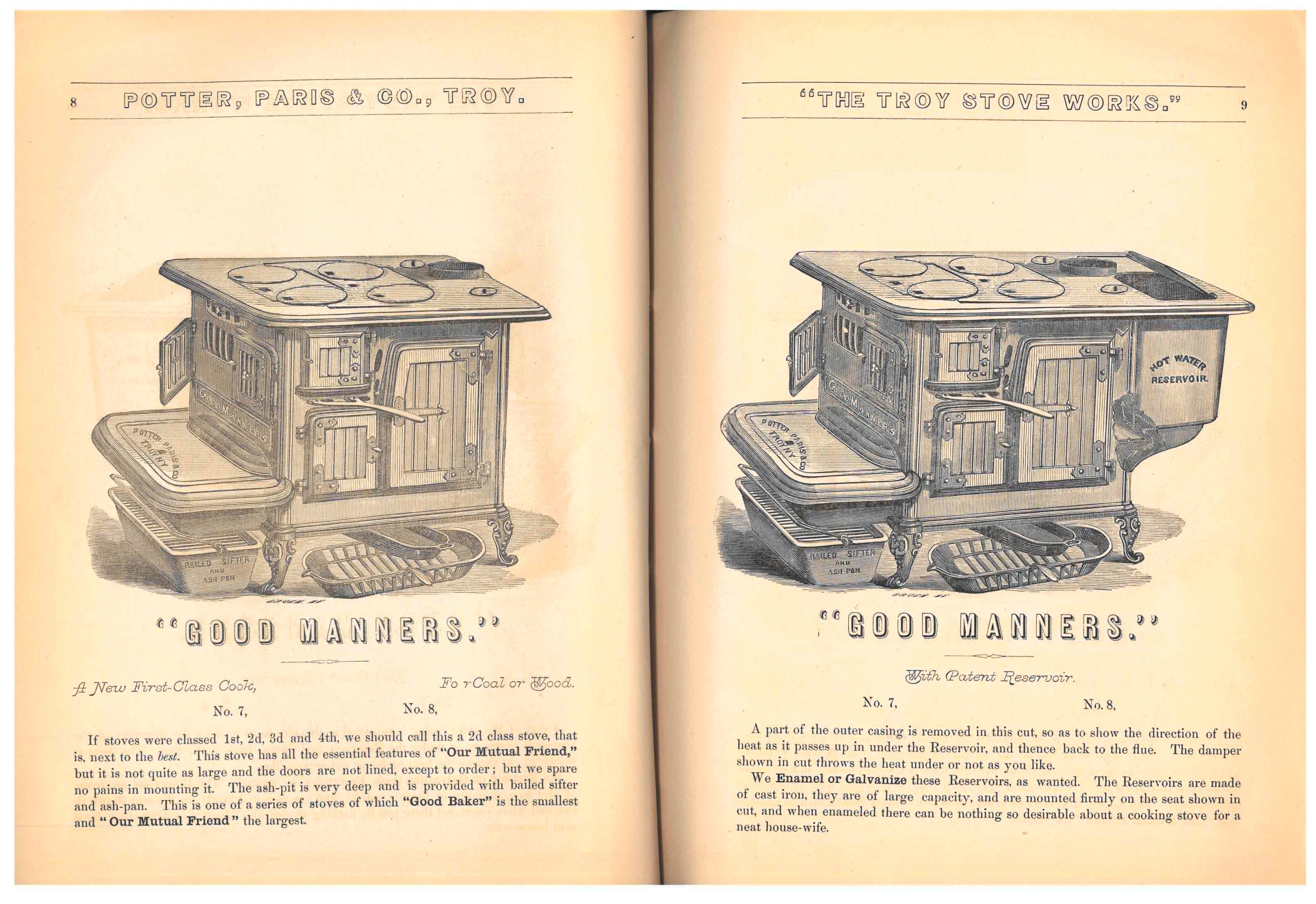

A variety of stoves, including ones of different sizes, are illustrated in this catalog. The stove named “Good Manners” which is shown below was intended for coal or wood. It was described as “next to the best” and included the same important features as “Our Mutual Friend” which is illustrated above, though not as large and without lined doors.

“Good Manners” was part of a series of stoves of which “Our Mutual Friend” was the largest and “Good Baker” was the smallest. The reservoir is shown in the illustration of the “Good Manners” stove below (right). The illustration includes arrows which “show the direction of the heat as it passes up in under the Reservoir, and thence back to the flue.”

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), pages 8-9, “Good Manners” stove (right image shows the stove with reservoir).

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), pages 8-9, “Good Manners” stove (right image shows the stove with reservoir).

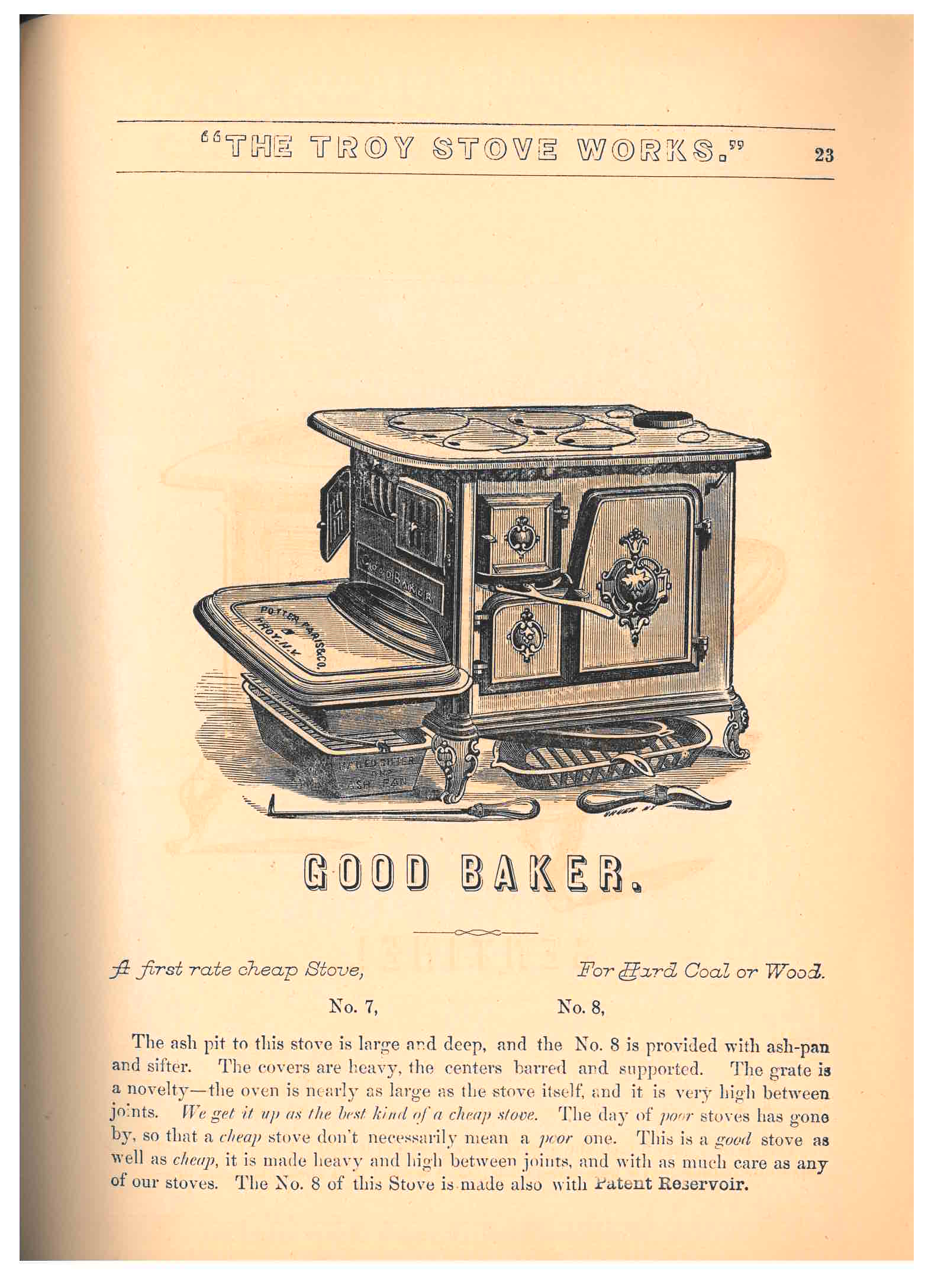

The smallest stove in that series, “Good Baker,” is illustrated below. Intended for hard coal or wood, it was described as “a first rate cheap Stove” and “a good stove as well as cheap.” According to this catalog, its oven was almost as large as the stove itself.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 23, “Good Baker” stove.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 23, “Good Baker” stove.

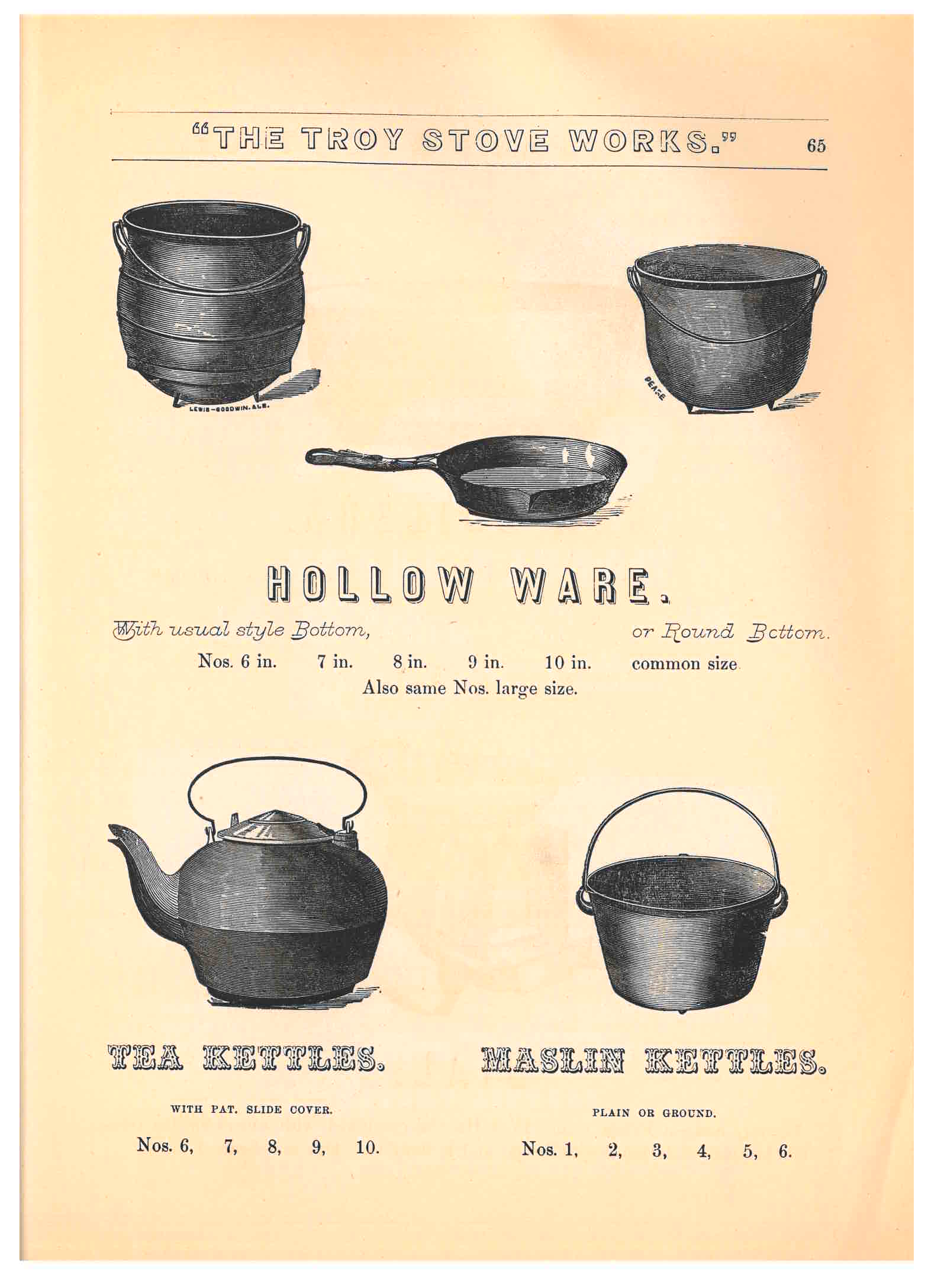

The catalog also includes pages on accessories for the kitchen. Below are illustrations of some kettles and a few pieces of hollow ware, such as pots and a pan.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 65, hollow ware and kettles.

Potter, Paris & Co., Troy, NY. Catalogue of Stoves (1866), page 65, hollow ware and kettles.

Catalogue of Stoves (1866) by Potter, Paris & Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Demystifying Information Literacy: From Buzzword to Classroom Resource

In the throes of my first year of pre-pandemic teaching, when I was fresh and green and hardly older (or taller!) than my students, the term Information Literacy meant something quite different to me, and surely to all of us, than it does now. Information Literacy was once a vague set of rules and tools that were scribbled aimlessly on a mental sticky note and stuck to the side of a metaphorical laptop – collecting dust in one’s periphery but never quite clearing into a sharp focus. Since then, the world has continued to turn at its promised pace as we have lived through a string of “unprecedented times” that I’m certain will be a truly riveting chapter in a history book one day. The utter bombardment of information and misinformation the public was forced to weed through, along with a growing culture of polarized media, and the breakdown of trust between news sources and the public, required us to start to think very critically about the information we were consuming.

Making sense of information became crucial in a tangible and immediate way. It could mean the difference between whether you keep yourself and your loved ones safe and healthy or not. It could determine if you sought medical care and what kind of care you sought. It could inform who you voted for, how you voted, and your trust in the voting system in general. On top of trying to think critically about the information I received myself, I was tasked with teaching my high schoolers how to make sense of it too as they experienced a seriously chaotic upheaval of their young lives. There was no real curriculum for this challenge that was tailored to students and digestible for a young audience. Information Literacy had been historically relegated to a quick lesson to be reviewed annually by English teachers through the groans and sighs of teenage opposition as they embarked on teaching the tenets of the classically dreaded 5-page research paper. The work I have been able to contribute to this summer is a direct solution to this very real, very problematic gap in Information Literacy tools for educators and students.

This summer, I have had the honor of working as an intern with the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Education Department to help create a digital series of collections that explore and explain key Information Literacy concepts and ideas. These collections have been carefully and lovingly curated specifically for K-12 educators and students. Through the efforts of myself, fellow intern Jason Cavallari, and our fearless, funny, and fierce leader Sara Cardello, we have been able to help fill that gap and build a comprehensive curriculum that provides a toolkit of skills, sources, tips, and tricks regarding Information Literacy. We used the Smithsonian’s own platform of Learning Lab to create beautiful, immersive, and interactive learning experiences that detailed the “ins and outs” of our topics, sourcing most of the images and content from our own galleries and collections at the Libraries and Archives.

Cover Page of Case Study: Internet and Media Sources collection.

Cover Page of Case Study: Internet and Media Sources collection.

The overarching theme of my contribution to this collection was maximizing its usability for educators. Though I am currently pursuing my Masters full-time at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and no longer breaking down Information Literacy to students, I wanted to make sure what were creating a true asset to those tasked with this undertaking. One of my first projects was to create a mechanism to elicit feedback on the usefulness of the tool as it currently stands and to disseminate this tool across teacher networks. Calling on my former Teach For America community in Eastern North Carolina, new and former colleagues, and local school teachers, we were able to gain some insight into how to enhance the collection for specific populations.

Next, I analyzed the collections and looked for “gaps” in the curriculum, viewing the collection through the lens of an educator who would want to use our resources to build a lesson around. We then built those collections to ensure that our series was well-rounded and robust. I figured the likelihood of highest engagement remained reliant upon this series being a “one stop shop” for those teaching Information Literacy. We wanted to ensure that individual work or group work could be done with the lessons we provide, that Information Literacy could be introduced in a day or that our materials could be used to build an entire unit on the subject, and that this series of collections became an all-inclusive toolkit that could be easily absorbed by all learners. I also sleuthed for connections between the content of our series, connecting dots and finding a flow for the collections to categorize them into groups. Our four major groups of collections revolve around the following topics: the Smithsonian’s role in increasing and diffusing knowledge, the many different types of sources and how to evaluate media and internet sources, core information literacy concepts, and information literacy in culture. I then supplemented these groupings by creating a case study for all of them that further dissected their teachings and promoted Smithsonian Libraries and Archives content.

Cover Page of Case Study: Bias & Fact vs. Opinion collection.

Cover Page of Case Study: Bias & Fact vs. Opinion collection.

After my case studies were built, the majority of the remainder of my time was dedicated to creating an online course using the Moodle platform that pulled apart and restitched our content for an entirely different audience. The Moodle course is geared towards the life-long learner – an adult who is seeking to broaden their horizons on the topic, sharpen their information literacy tools, or simply just be introduced to Information Literacy as a whole.

In addition to helping fill this gap, I’m most proud to have worked on a project that strives for the true democratizing of information literacy education. Our tools and resources are accessible for all, despite disparities in school funding. They are free to anyone and everyone – always. This project was such a labor of love for me, beyond the fact that I had longed for a resource like this as an educator myself, but because I truly believe in the message behind information literacy and the power that it holds. Albert Einstein once said “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious”. The lifeblood of Information literacy is being passionately curious.

At the core of information literacy is this notion of critical thinking, of a certain sustained and genuine curiosity. Knowledge is constantly heralded as the greatest equalizer, and learning how to be curious about knowledge is the mobilizing agent in making changes towards equality and equity. Information Literacy goes far beyond newspapers and magazines and teaches so much more than just identifying a source or how to properly use it. Information literacy is powerful and liberating. Information literacy models and rewards critical thinking by teaching how to ask arresting questions about bias and about motive and about implicit and explicit messaging. It lays the groundwork for justice and truth seeking through cultivating this passionate curiosity. Information literacy gives students, and everyone for that matter, that bright and flickering spark of eager investigation that can be lovingly tended into a flame that stokes change-making. Information literacy tells young people that it is okay to challenge the information you’re being given, what the information is teaching you to believe, the system giving you this information, and systems themselves.

This internship could not have better combined my past experiences, current schooling, and (hopefully!) future career into the most niche and rewarding learning experience. I’m honored and overwhelmed with gratitude to have been a tiny cog for a brief period of time in the radical, revered, respected, and ever-moving-machine that is the Smithsonian Institution.

Further Reading:

Wesley Chenault Named Associate Director for Strategic Initiatives and Programs

Wesley Chenault has been appointed Associate Director for Strategic Initiatives and Programs of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. In this inaugural role, Chenault will oversee outreach, communications, education and exhibitions. He will support Smithsonian Libraries and Archives colleagues in developing new initiatives and programs and develop and implement strategic initiatives within the unit, pan-institutionally across the Smithsonian as well as cultivate strategic collaborations with community partners locally, nationally and globally. Chenault will collaborate with advancement leadership to build programs related to fundraising, donor relations and the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board, as well as event concept and management for advancement activities. His work will raise the research profile of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, increasing knowledge sharing among Smithsonian partners, peer research institutions and international communities beyond.

“I am thrilled to welcome Wesley Chenault to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives,” said Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, director, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. “His creative leadership and wide-ranging experience will shape engagement and outreach for both longstanding partners and new and diverse audiences, ensuring a robust future and legacy for our newly-merged organization.”

Chenault holds over 20 years of experience in research settings, with a focus on rare and distinctive collections in museum, public and academic libraries. Most recently, he served as Director of the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University, where he oversaw collections, programs and research services. His prior positions include work with the Herndon Home, the Atlanta History Center, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History and Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries.

Wesley Chenault, Associate Director of Strategic Initiatives and Programs. Photo by Rachel Philipson.

Wesley Chenault, Associate Director of Strategic Initiatives and Programs. Photo by Rachel Philipson.

“It is my honor to join the world’s largest museum library and archives system at this historic time, building upon the incredible and important work being done,” said Wesley Chenault. “I look forward to working collaboratively with the Advisory Board, the Smithsonian internally and our many communities and partners to broaden the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ scope and add to its success locally, nationally and globally.”

Chenault has broad experience in education, developing syllabi and advising on curriculum development, serving on dissertation committees and leading initiatives in research settings. In addition to teaching undergraduate and graduate students in universities, he has developed internship programs, administered research and travel grant programs and served in roles such as reviewer, consultant and grant staff for humanities agencies including the Georgia Humanities Council, National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. In 2020, he was a participant in “Teaching from Digital Archives at Home and Around the World,” a summer teachers’ institute sponsored by Hemispheres, an international outreach consortium at the University of Texas at Austin.

Chenault is a published scholar, with articles authored and co-authored in edited volumes, such as Educational Programs: Innovative Practices for Archives and Special Collections and Queer South Rising: Voices of Contested Place, and academic peer-reviewed journals and encyclopedias, among them New Georgia Encyclopedia and the Journal of Southern History. With Stacy Braukman, Chenault is co-author of Gay and Lesbian Atlanta, a pictorial history.

Chenault has exhibited widely as an individual and in collaborations. For the latter, he was a founding member of idea collective John Q, whose interests in public scholarship, interventions and memory have been featured in educational programming and exhibitions across the nation, from the GLBT Historical Society Museum & Archives in San Francisco to the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia in Atlanta. Outside of the collective, Chenault’s curatorial work spans his career from exhibitions at the Atlanta History Center to Cornell University, where he was a co-curator for the exhibition, Social Fabric: Land, Labor, and the World the Textile Industry Created, which opened Nov. 4, 2022.

Chenault holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Auburn University, a master’s degree in women’s studies from Georgia State University and a doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. A member of several library and museum organizations, he has certifications from the Archives Leadership Institute from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Leadership Institute for Academic Librarians from Harvard University.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Opens “Nature of the Book”

Join us for a virtual tour on Tuesday, November 15th!

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives presents a new exhibition, “Nature of the Book,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History November 11. “Nature of the Book” will be on display through March 17, 2024.

What makes a book? Throughout history, books were handwritten, printed, bound and decorated using a wide variety of materials from the natural world. From leather coverings and paper derived from plants to mineral pigments and innovative recipes for inks, the early book was a combination of natural materials in the hands of skilled artisans. Influenced by the scarcity and abundance of commodities, global trade and economics, thrift and fashion, books could vary greatly in terms of materials, construction and purpose.

Throughout history, books were handwritten, printed, bound, and decorated using a wide variety of materials from the natural world.

Throughout history, books were handwritten, printed, bound, and decorated using a wide variety of materials from the natural world.

“Our research process involved teasing out the rich complexity of the history and materials used in hand bookbinding,” said Vanessa Haight Smith, head of preservation services at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and co-curator of “Nature of the Book.” “The exhibition gives us the opportunity to discuss that the use of natural materials and techniques haven’t followed a linear path; rather, they are intertwined and layered crossroads of global products and ideas.”

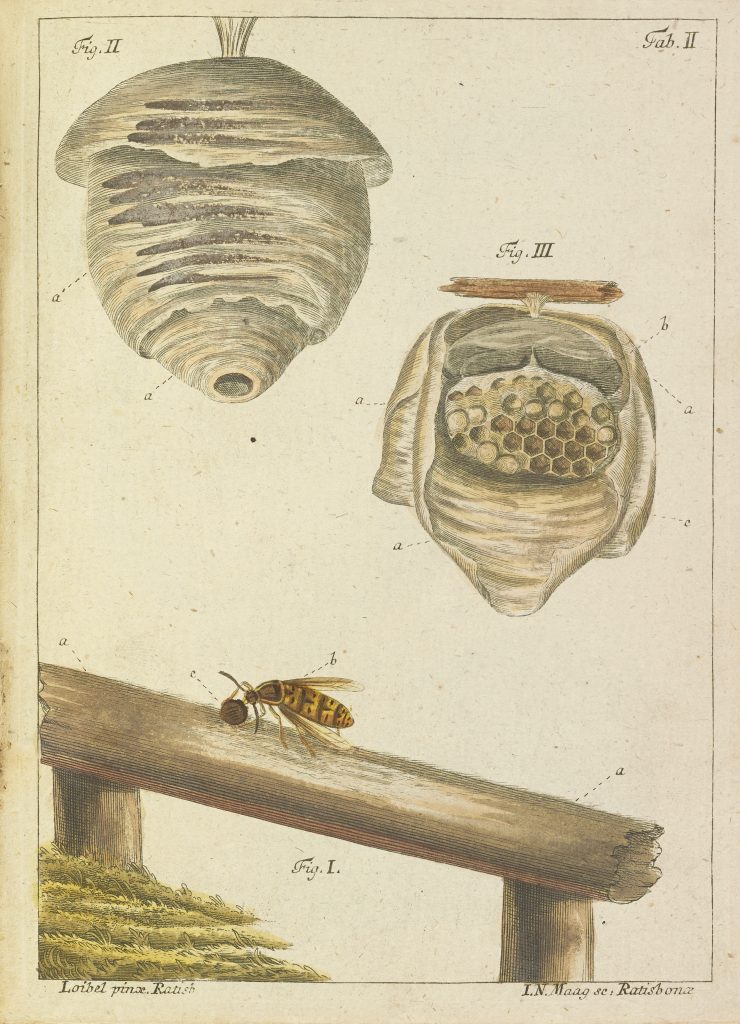

“Nature of the Book” explores books of the hand-press era (from the use of moveable type in Europe in about 1450 to the rise of mechanization in the 19th century) through the myriad natural materials—animal, vegetable and mineral—that went into their making. From essential ingredients like flax, leather, copper and lead, to the unexpected, like wasps and seaweed, the exhibition shows what the use of these materials can tell people about the book, touching on questions of use, process, global trade and economy.

The paperwasp’s habits of chewing wood fiber to create pulp for nests would eventually inspire thedevelopment of wood pulp paper in the 1800s. Jacob Christian Schäffer sought alternatives to linen rag paper. He published his findings, which included 82 handmade paper samples from a variety of local natural sources.

The paperwasp’s habits of chewing wood fiber to create pulp for nests would eventually inspire thedevelopment of wood pulp paper in the 1800s. Jacob Christian Schäffer sought alternatives to linen rag paper. He published his findings, which included 82 handmade paper samples from a variety of local natural sources.

“‘Nature of the Book’ delves into the material components of books from the expected, such as parchment, paper and leather, to the unexpected including semi-precious gems, arsenic and cochineal insects,” said Katie Wagner, senior book conservator at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and co-curator of “Nature of the Book.” “This exhibition appeals to newcomers to the topic as well as to bibliophiles.”

On display will be Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (London, 1729–1747), Francisco Hernández’s Nova plantarum (Rome, 1651) bound in tawed pigskin leather, Hokusai’s Hokusai Manga (Japan, Late Edo period, 1780–1868), John Addington Symonds’ Wine, Women, and Song (London, 1884) in an exquisite jeweled binding and a gold illuminated partial Qurʾan (Qajar-period Iran, c. 1800s).

Pig farming provided a source for sturdy bookbinding leather in Germanic Europe. Pigskin was often tawed, not tanned, resulting in a whitish appearance. Though printed in Rome, this book was likely bound locally by its Austrian owner.

Pig farming provided a source for sturdy bookbinding leather in Germanic Europe. Pigskin was often tawed, not tanned, resulting in a whitish appearance. Though printed in Rome, this book was likely bound locally by its Austrian owner.

Bookbinding to etching, papermaking to hand-coloring, typesetting to marbling and watermarking to gold tooling, “Nature of the Book” invites visitors into a fascinating exploration of the craft, innovation and ingenuity of hand-press bookmaking of centuries past. It tells a story of local resources and resourcefulness as well as global influence—from Asia, the Middle East and North Africa—that was essential to the Western book that is commonplace today.

To celebrate the opening of this new exhibition, we’re taking you on a free, virtual tour! Register now to get a closer look with Katie Wagner and Vanessa Smith in our next online program, November 15th at 6pm ET.

“Nature of the Book” is made possible through the support of The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board.

It’s Alive! Arion Press’ Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus

“It’s alive!” During the spooky season celebrated around Halloween, decorations and costumes of classic pop culture creatures abound, like Dracula, the Wolfman, and Frankenstein’s monster himself. Our modern conception of Frankenstein is a loveable zombie, tall and dopey with green skin and spiky hair, bolts and stitches. Originally published in 1818, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus actually tells the story of Dr. Victor Frankenstein and his ill-fated desire to create the “perfect being.” The author, Mary Shelley, explored the consequences of playing God, the corrupting influence of misdirected ambition, the possibilities and limitations of science. Frankenstein’s “Creature” has fascinated readers for over 200 years, and Shelley’s work has been published countless times since her lifetime.

Ship on the sea illustration. From Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Introduction by Todd Hosfelt, Artwork by Tim Hawkinson. San Francisco: Arion Press, 2019. Gift of Ronnyjane Goldsmith. Photo: Amanda Fiske.

Ship on the sea illustration. From Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Introduction by Todd Hosfelt, Artwork by Tim Hawkinson. San Francisco: Arion Press, 2019. Gift of Ronnyjane Goldsmith. Photo: Amanda Fiske.

The Smithsonian’s American Art and Portrait Gallery Library has recently acquired the 2019 rendition of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, published by Arion Press in honor of the original book’s 200th anniversary.

Arion Press specializes in handcrafted fine press books and is known for their collaborations with artists and authors. For Frankenstein, Arion teamed up with American sculptor Tim Hawkinson, working in the book form for the first time. The artist often uses common household or found materials in his inventive sculptural objects and kinetic machines. For this publication, Hawkinson devised a unique technique to create the accompanying images. Affixing a hypodermic needle to a fountain pen and creating a built-in inkwell that consisted of a soda bottle filled with ink, Hawkinson suspended the entire contraption from the ceiling of his studio. The large paper was pinned to a turntable on the wall, and each horizontal mark with the delicate tip of the needle and the turning of the paper on the turntable caused the ink to dribble in unexpected ways. Not only is this artistic technique unique, but this system was just unwieldy enough to seemingly have a mind if its own, an autonomous creation that evokes the novel. The hypodermic needle echoes how Dr. Frankenstein used syringes to bring his creation to life, and how they defied his expectations. The hundreds of straight and sketchy lines come together to create an eye-catching spooky, dreamy vibe that compliments the story.

The Smithsonian holds the deluxe edition of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, presented in a wooden box carved in Hawkinson’s same sketchy lines with the image of a ship’s mast and rigging. Each chapter in the book has one of the nine prints created for this volume, giving the reader an image that compliments the narrative as it unfolds.

Wooden deluxe slipcase from Frankenstein.

Wooden deluxe slipcase from Frankenstein.

Interestingly, Hawkinson’s drawings never show the Creature itself, furthering the interpretation that the Creature was perhaps not the true monster, and that it was Dr. Frankenstein himself whose ambition ignored the rules of nature, pushing the scientific boundaries until his own creation destroyed him. There is no correct answer, leaving the reader to speculate and draw their own conclusions.

Tim Hawkinson in action, with hypodermic needle + soda bottle fountain pen and Frankenstein drawings. Photo: Arion Press

Tim Hawkinson in action, with hypodermic needle + soda bottle fountain pen and Frankenstein drawings. Photo: Arion Press

You can read more about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and how she was inspired by the history of 19th-century chemistry and electricity in the Body Electric in the Smithsonian Libraries online exhibition for Fantastic Worlds: Science and Fiction, 1780-1910. In addition, you can read more about Arion Press’ Frankenstein and their production process in their full prospectus on the Arion Press website. Other resources consulted include The Many Editions of Frankenstein, a blogpost from the University of North Georgia Press, October 26, 2018, and Pace Gallery’s information on artist Tim Hawkinson (both accessed 10/28/2022.)

This blogpost was co-written by Amanda Fiske, an intern through SAAM’s Advanced Level Program, and working with the AA/PG Library for the full academic year. She is currently a student in the Master’s in Library and Information Science program at the University of South Florida.

AVMPI: From Aquariums to Archives

During American Archives Month, we’re highlighting the work of our Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative in a series of posts. This is the third post in the series.

Still frame taken from Siobhan Hagan’s home movies of her father documenting the documentation of a trip to the National Aquarium in Baltimore in 1992.

Still frame taken from Siobhan Hagan’s home movies of her father documenting the documentation of a trip to the National Aquarium in Baltimore in 1992.

As a kid growing up in the Baltimore-Washington area, I frequently visited Smithsonian museums for field trips throughout my adolescence. I never fully realized how lucky I was until I moved away for several years and learned that many people don’t have access to free, world class museums at their doorsteps. And years later, I find my luck cup runneth over, now working at this renowned institution with some of the most inspiring colleagues and collections as the new AVMPI Coordinator (Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative).

It certainly has been a winding road that brought me here. The first thing I ever wanted to be was a dolphin trainer. This was inspired by many visits to the National Aquarium in Baltimore along with hours watching re-runs of the 1960s TV show “Flipper”. Eventually I realized it was more the TV part that intrigued me than marine mammals (although those are super cool too). So I studied film and video production in undergrad and worked in the entertainment industry after college, but it was nowhere near as fun or fulfilling as I had hoped. I applied to and was accepted into the NYU Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, graduating in 2010 (alongside my AVMPI colleague Walter Forsberg!).

Since then, I have worked at a variety of organizations: large academic libraries, small special collections departments, aquariums (yes, I got to fulfill that childhood dream of caring for dolphins…at least videos of them), arthouse theaters, public libraries—and I even contracted with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art for a few months inspecting and rehousing motion picture film materials. My passion is the preservation and access of regional audiovisual materials, local television, home movies, and community and personal archiving. In 2016 I merged these interests, along with my love for my hometown of Baltimore, Maryland, to start up and run the nonprofit organization MARMIA (which stands for the Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive). I have also been working full-time since 2018 at DC Public Library as the Memory Lab Network Project Manager, helping to build personal archiving capacity in public library spaces and programming across the United States.

In that job, I was able to work with incredibly diverse librarians, archivists, and memory workers who were determined to help their communities to preserve their individual histories. Though we all came from different corners of the country, we joined together to create a community of practice-based solutions for our shared problems. Now as the Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative Coordinator, I get to work with an incredibly diverse set of curators, archivists, librarians, conservators, and more to address the complex challenge of preserving the moving images and recorded sounds of the world’s largest museum, education, and research institution. While the mission may seem impossible alone, this new collaborative approach across many Smithsonian units will make the goals of AVMPI possible.

Video rack in the progress being built at the National Museum of American Indian, Cultural Resource Center.

Video rack in the progress being built at the National Museum of American Indian, Cultural Resource Center.

My first tasks are to build-out the already robust audio and video preservation transfer suites in several units along with refining workflows to be as efficient and effective as possible for everyone involved. The most exciting part of the AVMPI project is the people: my future AVMPI teammates will utilize the transfer suites and workflows to increase access to Smithsonian collections for all: browsers online, in-person and virtual exhibits, curators, researchers, artists, and more. We also plan to make our workflows, tools, and lessons learned available online for open access to all. I am looking forward to when AVMPI will be able to share the amazing audiovisual media we have saved at the Smithsonian—hopefully there will be some footage of a dolphin or two.

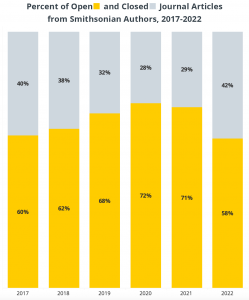

Open Access Week and Smithsonian Research Online: An Update

Open Access Week is the perfect excuse to talk about a favorite topic of mine—making Smithsonian research more open! A couple years ago, I wrote a post about a Tableau dashboard released by Smithsonian Libraries and Archives that explores the Open Access status of publications from Smithsonian-affiliated authors. Since then, we have taken things a step further, using the same source data to enhance Smithsonian Research Online directly by including links to open access versions of Smithsonian journal articles thanks to Unpaywall’s API. This means we have added over 8,000 links to journal articles anyone can read regardless of affiliation.

Smithsonian Research Online is a Libraries and Archives program to track the research output of the Smithsonian. With nearly 100,000 records, the system spans the life of the Smithsonian, with an average of 2,500-3,000 new records added each year. One of our goals with Research Online is to make sure that this research is accessible and available to fulfill the mission of the institution—”the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

For the past few years, we have been using Unpaywall’s openly available data about the open access status of journal articles. Their API includes a status designation for the different ways in which journal articles are accessible. As you may know, the traditional model of scholarly publication is that authors submit publications to a journal, and that journal will charge for access. Much of this cost burden has been borne by libraries in particular, as we want to make as much available as possible (naturally!). This is what “closed” means in this context—it’s in a journal you need to pay to access.

Beyond that, there are many ways in which a journal article can be “open.” This includes journals where the entirety is freely available (often referred to as “gold” open access), individual articles made available for free in an otherwise for-pay journal (deemed “hybrid” by Unpaywall if there is a specific license for availability assigned to the article, or “bronze” if no such license exists but it is still available without paywalls), and finally articles can be made available in a digital repository (“green” open access), where a version of an article is accessible to the public.

These colorful terms can be simplified into two camps: open or closed. Librarians know that users care less about the distinction than we do, but we really care about the distinction! It helps us assess where scholarly communication is going and helps us think about where to put our often-diminishing resources.

Beyond simply analyzing our content, in 2022 we took things a step further by integrating data from Unpaywall directly into our system. First, we looked at what data was available from Unpaywall. Their API provides links for each way a research article might be open access—whether it was in a journal that is open, or in a repository where a researcher shared it. They even include many that are both open from a publisher and also deposited in multiple repositories. (As of today, there is one article that is available openly from the journal but also deposited in 63 separate repositories! To each their own…) We took this data and determined that we needed a separate table in our database to handle links from our different data sources: Unpaywall, links we already had to our own digital repository, and links that come from the original ingest of metadata (via Zotero or our own internal webforms). With these multiple sources, we decided on a hierarchy of which link to include in our results. First, we wanted to link to our own copy of something in our repository. If that wasn’t available, we felt the next best link to add was from Unpaywall. Finally, if we had neither, we would go with the link provided, even if it wasn’t always a link to an open access copy. Thanks to our data developer Kristina Heinricy, this whole process of taking our publications, searching for them in Unpaywall, and getting back the multitude of possible links has been fully automated and integrated into our system. This has resulted in over 8,000 new links to fully open content being added to our records!

Many Smithsonian scholars are making their research open by publishing their papers in open access journals or making it publicly available in repositories, either because grant funding mandates it, they are dedicated to public access, or simply because an open access journal is the best journal for their research. Of course, the recent OSTP guidance making federally funded research immediately available plays no small part in this. Regardless of the intentions for publishing, the trend is undeniable. While embargo periods on sharing and the general lag in time for making articles available in repositories is evident in 2022 and some of 2021’s bars, this chart demonstrates that more Smithsonian research is available today than five years ago.

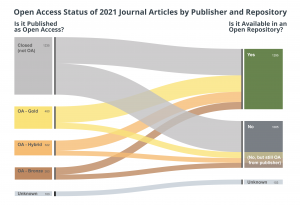

While we don’t capture the exact date and time when articles become open access, there is an inherent time delay between when something is published as open and when it becomes open through depositing it in a repository. We can visualize that time difference using an alluvial diagram. This one I made using RAWGraphs.io (with some tweaking in Illustrator). It helps to tease this out for a couple of reasons. First, we can distinguish things published open and things that end up open via repositories. But the interesting aspect to me is the overlap of items that are published as open and presumably will remain open that end up in a repository. It seems like an obvious redundancy. While it is not discouraged, I would much rather see more of the closed articles end up in repositories than open ones!

Now that we have this data, the future beckons! There are more ways this data could be put to work. One way might be to upgrade our user interface to point out which items are open and which are still behind paywalls. It should certainly relieve the labor of one-by-one evaluations of items. If the object is open, then maybe we don’t need to rush to deposit it in a repository as it is easily accessible already. I’ve pointed out some trends that I’ve seen, and some hopefully interesting insights. (You can see more about the program in our Annual Reports, too.)

What would you like to know about Open Access? Where would you like to see us take this?

Expressing Elegance in a Funeral Procession

The Trade Literature Collection gives us a small glimpse into the past. It includes catalogs on a variety of topics, including undertakers’ supplies. These catalogs illustrate coffins, grave guards, and even fashion for the deceased. One of these catalogs feature hearses for funerals from long ago.

The trade catalog is by Merts & Riddle and is untitled though the front cover points out they are “Coach and Hearse Builders.” Besides being untitled, the catalog is also undated. However, we believe it was published sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, front cover.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, front cover.

As we learned from the front cover, Merts & Riddle built both hearses and coaches, or carriages. The introductory page also mentions they had “many years’ experience” in that particular field. All of the hearses in this catalog are horse-drawn with glass sides making the coffin clearly visible to all who passed by.

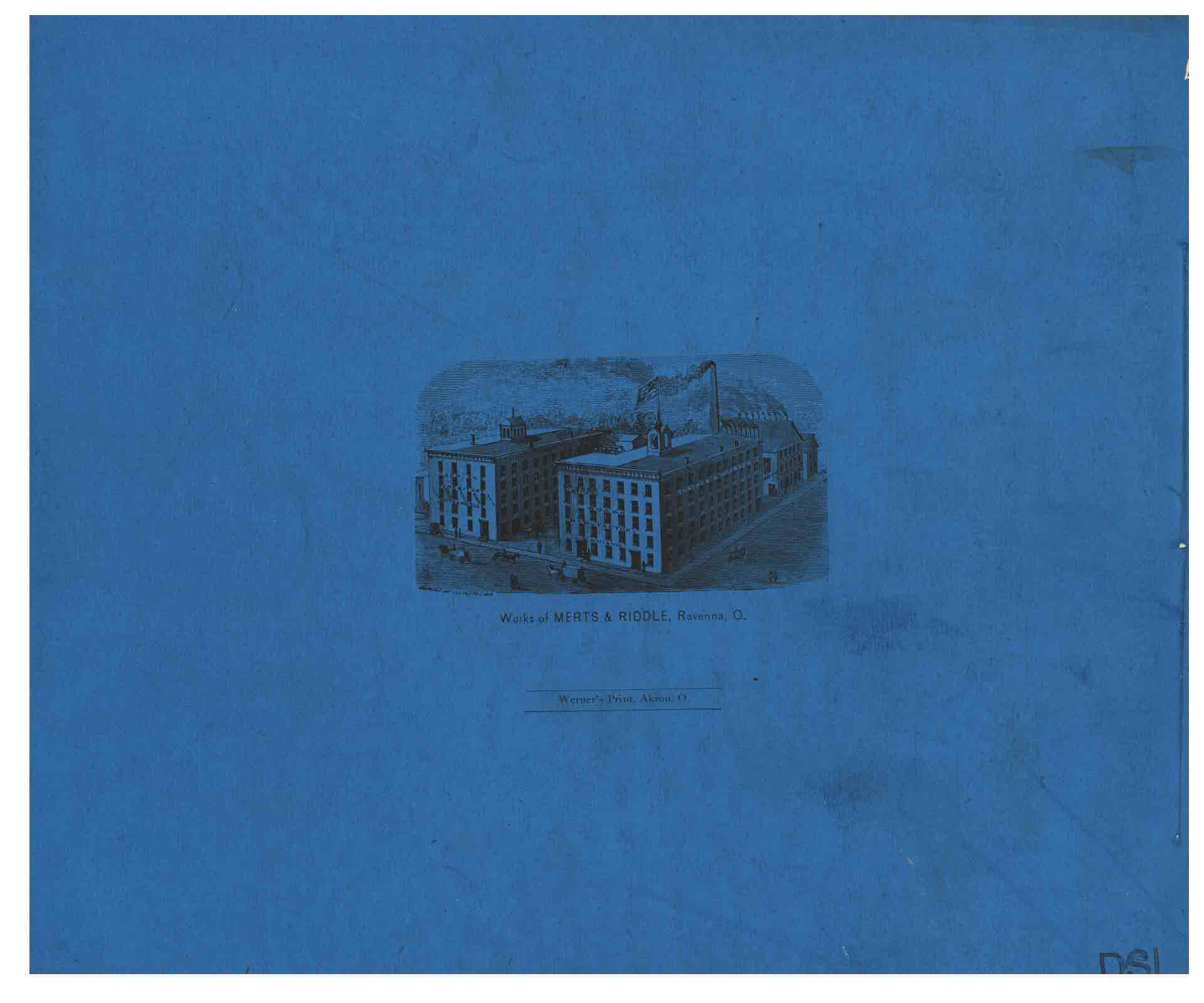

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [1], introductory page.According to the catalog, Merts & Riddle regularly kept their factory stocked. It mentions they always had “all finished, ready for shipment, thirty thousand dollars’ worth of Hearses, and as many coaches…” Specific prices are not included, though it indicates savings for the customer, specifically the ability to save $200-$500 on the cost of a hearse. Customers were encouraged to visit the factory, peruse the selection, and choose direct from available stock. Below is an illustration of the works, or factory, of Merts & Riddle in Ravenna, Ohio.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [1], introductory page.According to the catalog, Merts & Riddle regularly kept their factory stocked. It mentions they always had “all finished, ready for shipment, thirty thousand dollars’ worth of Hearses, and as many coaches…” Specific prices are not included, though it indicates savings for the customer, specifically the ability to save $200-$500 on the cost of a hearse. Customers were encouraged to visit the factory, peruse the selection, and choose direct from available stock. Below is an illustration of the works, or factory, of Merts & Riddle in Ravenna, Ohio.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, back cover, Works of Merts & Riddle in Ravenna, Ohio.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, back cover, Works of Merts & Riddle in Ravenna, Ohio.

The introductory page also mentions their aim, or goal. This was “constant improvement in style, durability, and elegance.” Many of the funeral cars pictured in this catalog are fitted with curtains around the glass as well as other decorative elements, such as urns or, like the hearse shown below, lamps and hand-carved pillars.

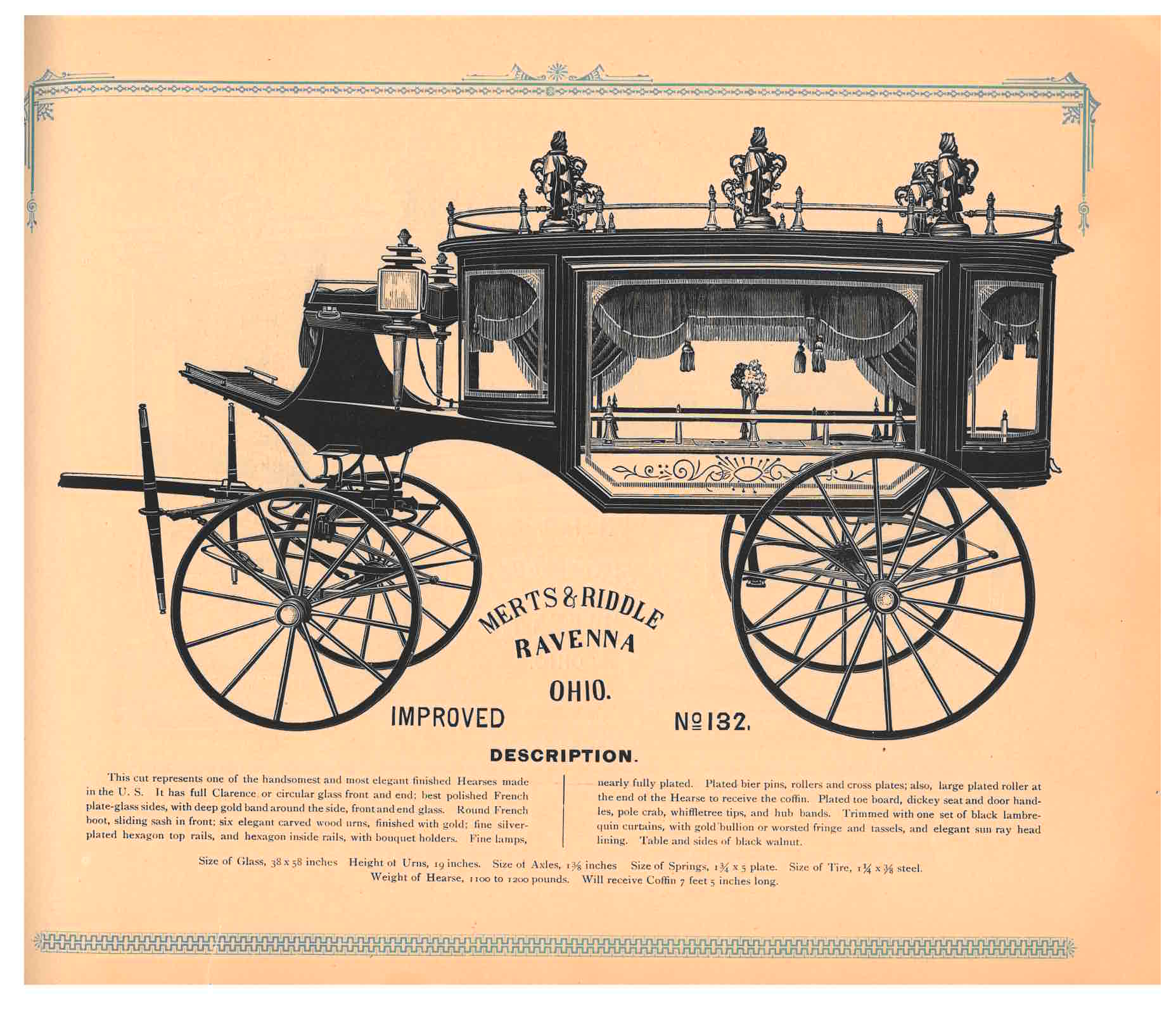

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [2], horse-drawn hearse.Improved No. 132, shown below, was fitted with sides made of polished French-plate glass along with circular glass at the front and back of the hearse. Black Lambrequin curtains elegantly hung on the windows above where the coffin would be placed. These curtains were trimmed with gold bullion or worsted fringe and tassels.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [2], horse-drawn hearse.Improved No. 132, shown below, was fitted with sides made of polished French-plate glass along with circular glass at the front and back of the hearse. Black Lambrequin curtains elegantly hung on the windows above where the coffin would be placed. These curtains were trimmed with gold bullion or worsted fringe and tassels.

This particular hearse fit a coffin measuring seven feet five inches long. A roller at the end of the hearse aided attendants in positioning the coffin. Inside the hearse, a hexagon-shaped rail with bouquet holders for flowers surrounded the coffin. Another hexagon-shaped rail adorned the top of the hearse along with six carved wood urns. A decorative, geometric pattern with what appears to be sun rays adorned the side of the hearse. The driver sat on a “dickey,” or exterior, seat.

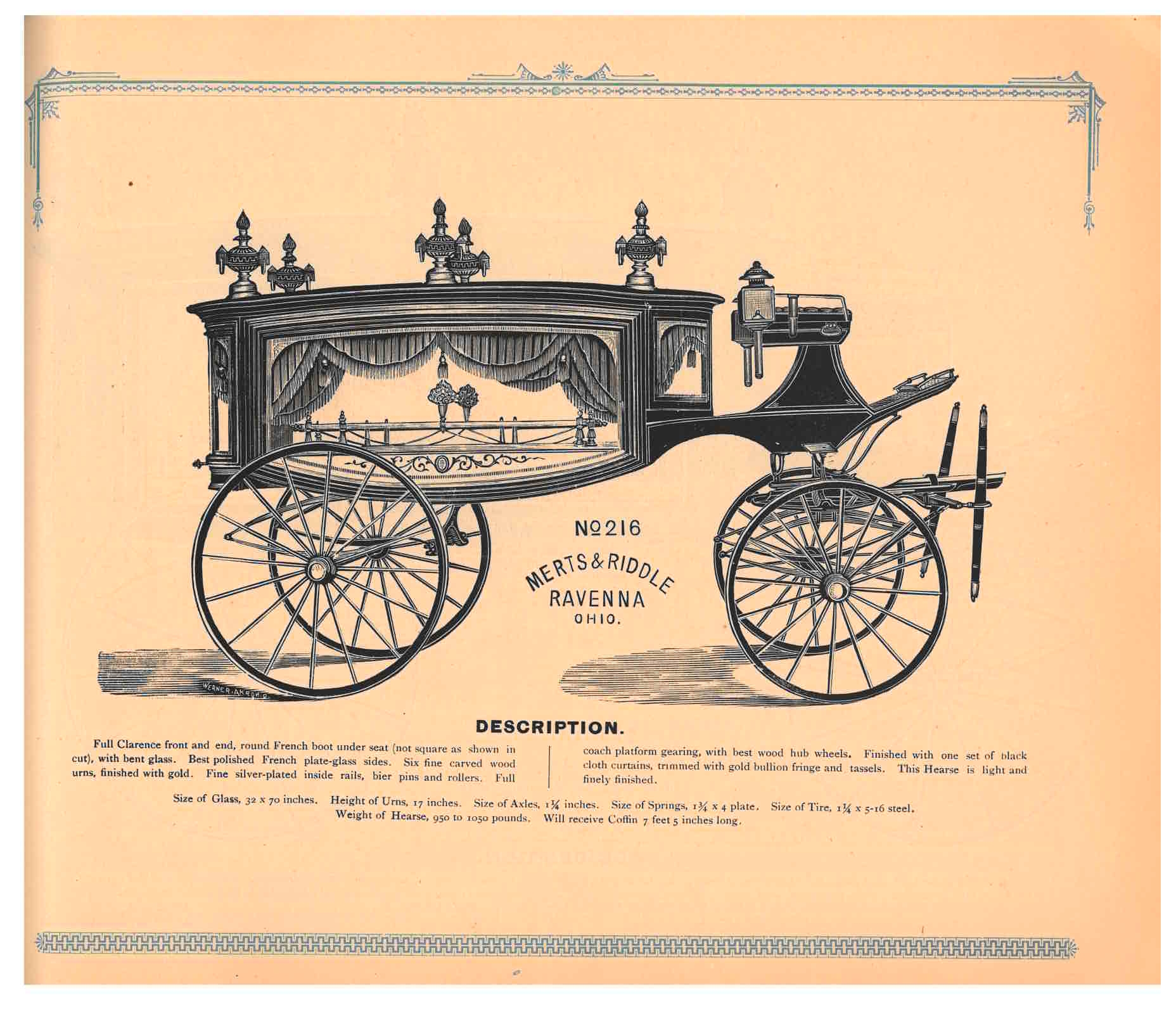

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [3], Improved No. 132 horse-drawn hearse.Hearse No. 216, shown below, was also built with French plate glass sides along with glass in the front and back. It included many of the same embellishments, such as wood carved urns, interior rails around the coffin, and black curtains finished with gold bullion fringe and tassels. However, this one was described as a “light” hearse. It weighed 950 to 1050 pounds in contrast to Improved No. 132 which weighed a bit more at 1100 to 1200 pounds.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [3], Improved No. 132 horse-drawn hearse.Hearse No. 216, shown below, was also built with French plate glass sides along with glass in the front and back. It included many of the same embellishments, such as wood carved urns, interior rails around the coffin, and black curtains finished with gold bullion fringe and tassels. However, this one was described as a “light” hearse. It weighed 950 to 1050 pounds in contrast to Improved No. 132 which weighed a bit more at 1100 to 1200 pounds.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [7], No. 216 horse-drawn hearse.Besides hearses, Merts & Riddle also built coaches, or carriages. One of these carriages, No. 236, is shown below. Perhaps it was used for the family of a loved one during a funeral procession to the cemetery. Its interior was decorated with green Morocco or green cloth and included a “silver toilet set” for its occupants to freshen up during travel. The windows were made of crystal plate or beveled-edge glass, and the carriage driver sat in an exterior “dickey seat” just like the hearse drivers.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [7], No. 216 horse-drawn hearse.Besides hearses, Merts & Riddle also built coaches, or carriages. One of these carriages, No. 236, is shown below. Perhaps it was used for the family of a loved one during a funeral procession to the cemetery. Its interior was decorated with green Morocco or green cloth and included a “silver toilet set” for its occupants to freshen up during travel. The windows were made of crystal plate or beveled-edge glass, and the carriage driver sat in an exterior “dickey seat” just like the hearse drivers.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [13], No. 236 horse-drawn Coach.This untitled and undated Merts & Riddle trade catalog, possibly published in the late 1800s or early 1900s, illustrating hearses and coaches is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Merts & Riddle, Ravenna, OH. Untitled Merts & Riddle trade catalog, undated, unnumbered page [13], No. 236 horse-drawn Coach.This untitled and undated Merts & Riddle trade catalog, possibly published in the late 1800s or early 1900s, illustrating hearses and coaches is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

AVMPI: Curating a Diverse and Dynamic Audiovisual Collection

During American Archives Month, we’re highlighting the work of our Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative in a series of posts. This is the second post in the series.

694,539?

Exactly how many audiovisual collection item films, videos, and audio recordings does the ‘Nation’s Attic’ hold? How can we ‘sunlight,’ ‘give voice to,’ digitize, preserve, make accessible, listen to, and otherwise watch them? Where did they come from? What do they mean?

Still image of a conservator from an unidentified Smithsonian television program. Courtesy of the author’s personal film collection.

Still image of a conservator from an unidentified Smithsonian television program. Courtesy of the author’s personal film collection.

These are a mere handful of the thrilling, confounding, and fundamental questions that face the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ new pan-institutional Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI) team and its institutional collaborators. As the AVMPI’s Curator of Recorded Media, I join the brilliant and entrepreneurial AVMPI project Coordinator Siobhan Hagan, along with five other soon-to-be-hired federal employees for the exciting and daunting opportunity to provide the American public some answers.

Despite how ‘new’ the Initiative may seem, our fearless Team Leader Alison Reppert Gerber has already won the Association of Moving Image Archivists’ prestigious Alan Stark Award for her 7+ years commitment to laying the groundwork for the Initiative. With generous and strategic fiscal resource commitments from the Smithsonian’s National Collections Program, unit-sponsorship from the Libraries and Archives, and as the product of tireless efforts by audiovisual media collections managers, archivists, conservators, curators, historians, and enthusiasts since the 1970s, the AVMPI is the result of dozens of Institutional staff and contractors across more than four decades.

Like Secretary Bunch, my Smithsonian mentor Dr. Rhea Combs, and many others in public service at the Smithsonian before me, I am fortunate to return to the Smithsonian for ‘Take 2’ after several years away. As a Media Archivist from 2014-2018 I helped to found the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s media digitization and conservation department, helped build the Oprah Winfrey Theatre’s cinema exhibition facilities, and co-chaired the Robert F. Smith Fund and its digitization programs. Since then, I have worked as Adjunct Faculty at New York University, as a Fulbright Specialist in Library Science in Mexico City, and as an archival producer for documentary film projects at the New York Times and National Film Board of Canada. In my role as AVMPI Curator of Recorded Media researching, selecting, prioritizing, and contextualizing the vast number of audiovisual media at the Smithsonian are primary goals.

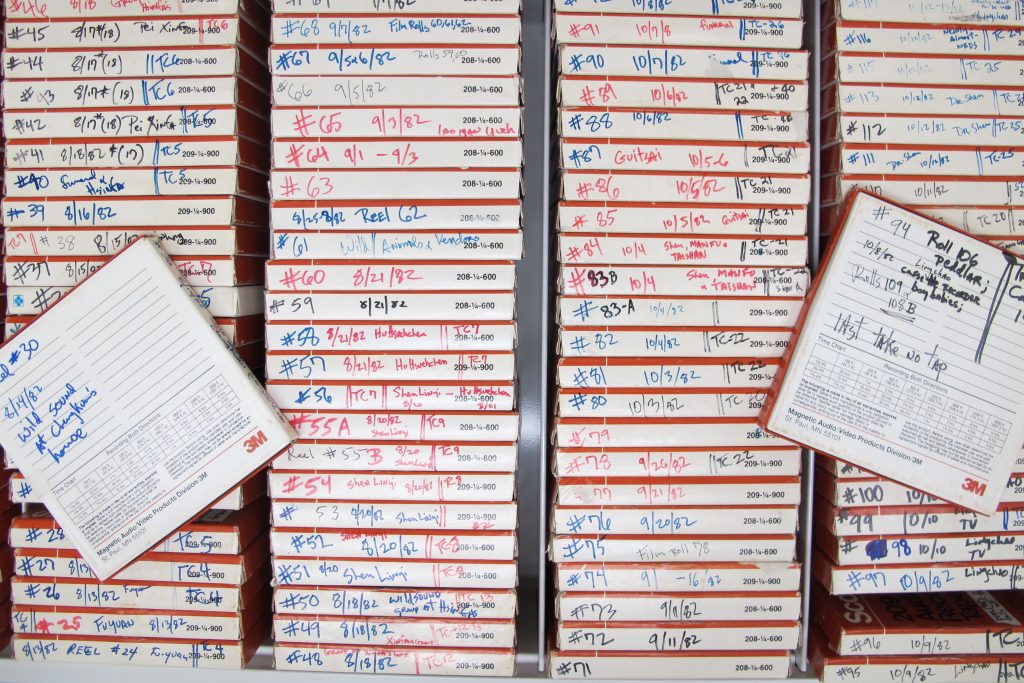

Two-inch quadruplex videotapes line the shelves at the Human Studies Film Archive, Smithsonian Institution. Image courtesy of Daisy Njoku.

Two-inch quadruplex videotapes line the shelves at the Human Studies Film Archive, Smithsonian Institution. Image courtesy of Daisy Njoku.

Collections materials held on certain ‘legacy’ analog formats, like the travelogue television programs held on the Hal and Halla Linker Film and Video Collection [HSFA 2002.16] two-inch quadruplex videotapes seen in the image above, are at specific risk of loss and are an immediate digitization priority for the AVMPI.

UNESCO believes that by 2025:

A number of factors will coalesce to make the digitisation of magnetic media increasingly difficult and prohibitively expensive: analogue video and audiotape, as well as early digital tape formats, will be effectively inaccessible due to the practical inability to maintain playback equipment, the gradual loss of experienced analogue-to-digital-transfer engineers, and the general degradation of the carriers themselves.

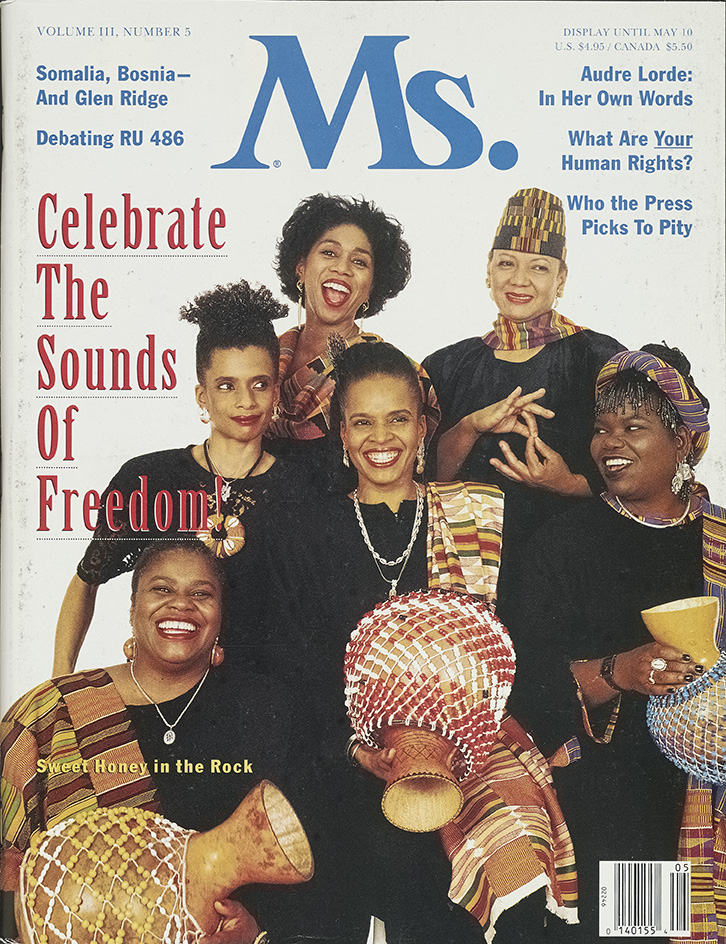

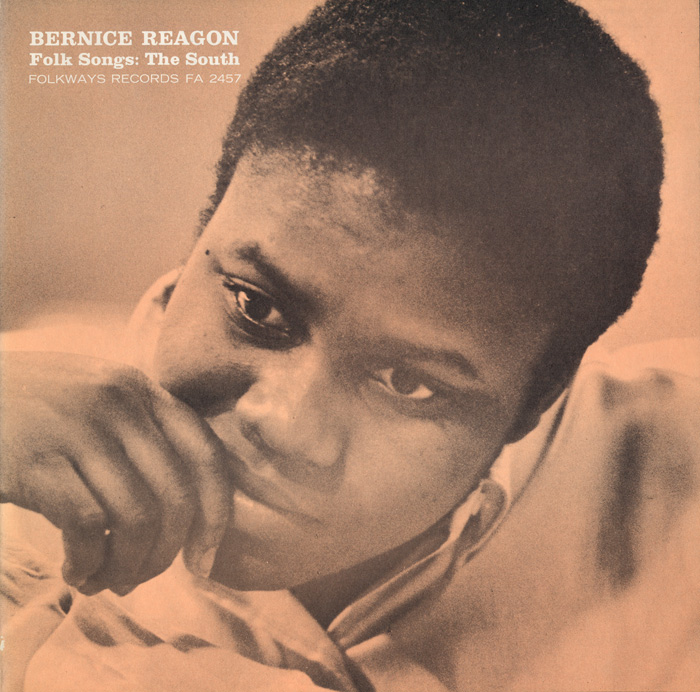

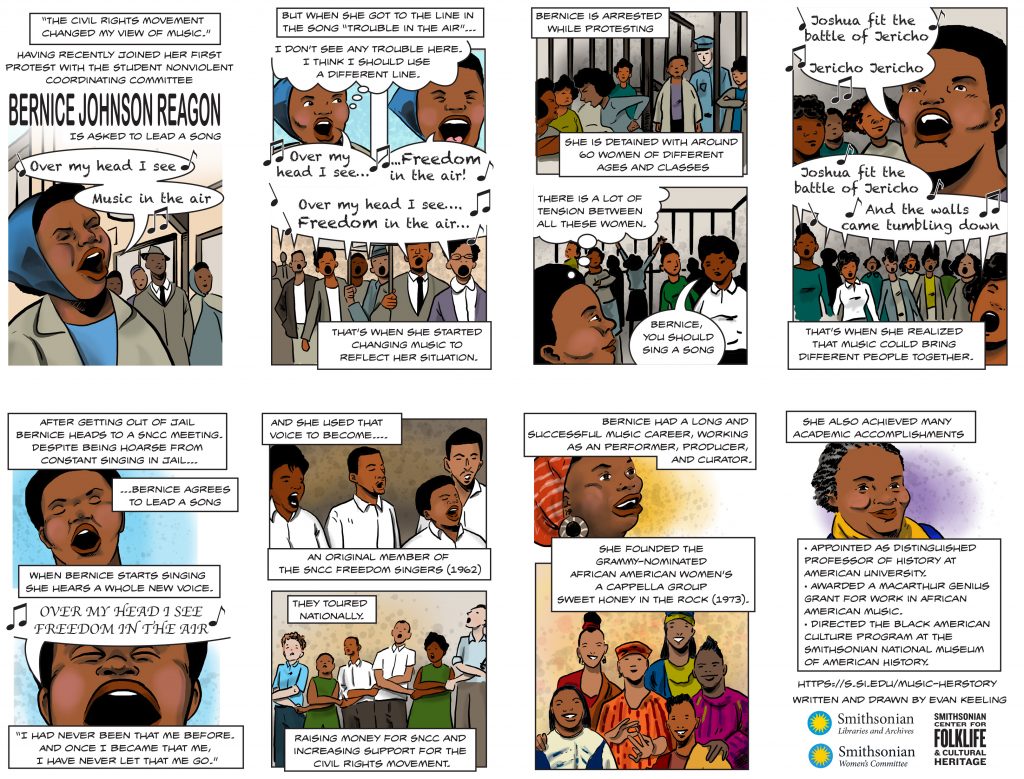

Other SI collections originally recorded on half-inch open reel magnetic videotape, like the substantial events documentation by Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage’s Ralph Rinzler in the 1970s, and by the Bernice Johnson Reagon-led Program in African American Culture Collection [NMAH-AC.0408] circa 1979-2004, fall into the same category.

Of course, sheer factory-line curatorial selections based on format obsolescence would be dull. In selecting and prioritizing material for preservation and digitization we hope to amplify stories about women, people of color, laborers, and changemakers, already present in Smithsonian collection holdings, yet buried due to their existence on inaccessible analog audiovisual formats. Other materials have simply not been fully-processed due to resource scarcity and we are excited to hopefully leverage AVMPI resources to digitize and make accessible such material as outer space films contained in the Sally K. Ride Papers [NASM.2014.0025], and oral histories about early twentieth-century African American cinema exhibitors and circuits in the US in the Pearl Bowser Collection [NMAAHC.2012.79].

Tapes and tapes and tapes and tapes. Image courtesy of Daisy Njoku.

Tapes and tapes and tapes and tapes. Image courtesy of Daisy Njoku.

Because those of us with first-hand working knowledge realize how seriously amazing the Smithsonian’s audiovisual media collections are, the AVMPI also seeks to prioritize preservation and digitization of material in support of ongoing exhibitions and new museums—like the American Women’s History Museum and the National Museum of the American Latino. We believe our institutional audiovisual collections should be the first choice for inclusion in topically relevant exhibitions and making them easily-accessible in digital form will enable more of that.

This past week, for example, we made a list of all baseball-themed media to complement the current “¡Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues: En los barrios y las grandes ligas” exhibition at the National Museum of American History and the “Baseball: America’s Homerun” exhibition set to open at the National Postal Museum next April 2023. Materials like the 1941 Harry Carney home movies of Duke’s band playing baseball contained in the Ruth Ellington Collection of Duke Ellington Material [NMAH.AC.0415], and oral histories from African American players in celebration of their contribution to our national pastime that form part of the Atlanta Interfaith Broadcasters Oral History Collection [ACMA.009-01], are wonderful and rich recordings that deserve wider audiences than they have received to-date. After all, we like to think that’s the reason that the Smithsonian collected them in the first place.

Before I go on too long, I will add that questions and paradigms of pure intellectual curiosity pervaded curatorial discussions in our initial summer months of the 5-year AVMPI initiative:

- What was the first documented film screening held at the Smithsonian? (One of the earliest documented film screenings in the Baird Auditorium took place during on July 16, 1914, consisting of: “illustrations of marine life below the surface of the sea at the Bahama Islands by means of moving pictures. The films were the first of their kind known to have been taken, and this was the first occasion of their public display, arranged through the courtesy of the Submarine Film Corporation.”Smithsonian Institution.Annual Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 1915. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. (1915): 37.)

- What other kinds of films, lectures, and performances (and documentation recordings thereof) occurred in the Baird Auditorium—which was the Institution’s primary auditorium for a major part of its history? (Check out a burgeoning Wikipedia entry about the Baird for some of those answers).

- What were the first media collections items acquired by the Smithsonian? (Still working on that one…)

- What exactly is the story behind that cool 16mm film fragment about the Smithsonian Institution from 1939 (voice-over: “Washington: the most beautiful city in the world…”) that filmmaker, Other Cinema curator, and motion picture living legend Craig Baldwin mysteriously mailed us?

The answer to this last puzzle will be addressed in a future post, and we encourage readers to check back with the Libraries and Archives site for all future AVMPI news, blogs, and digitized streaming collections.

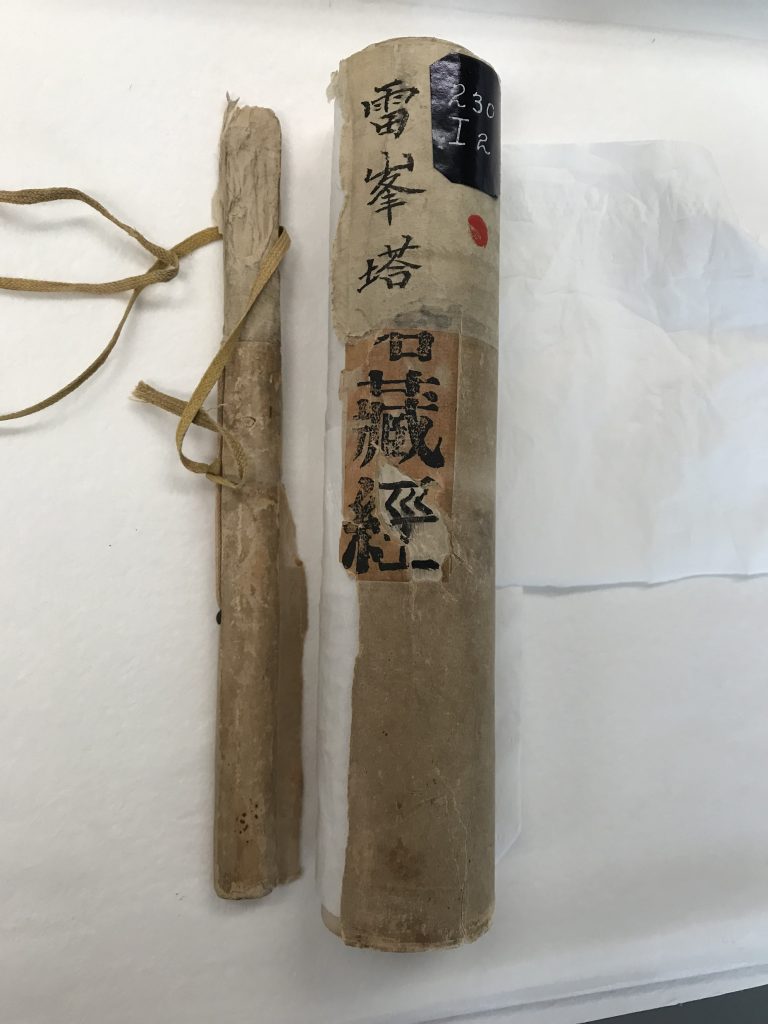

The Road to Recovery for a Chinese Sutra

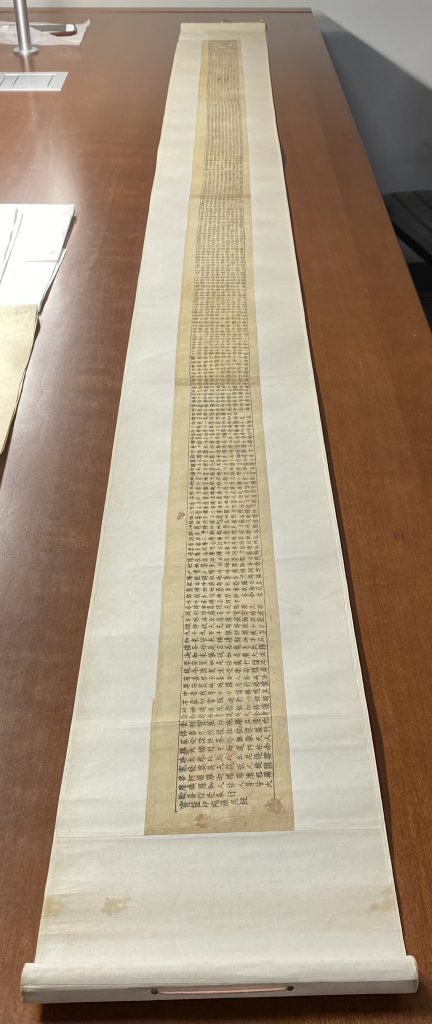

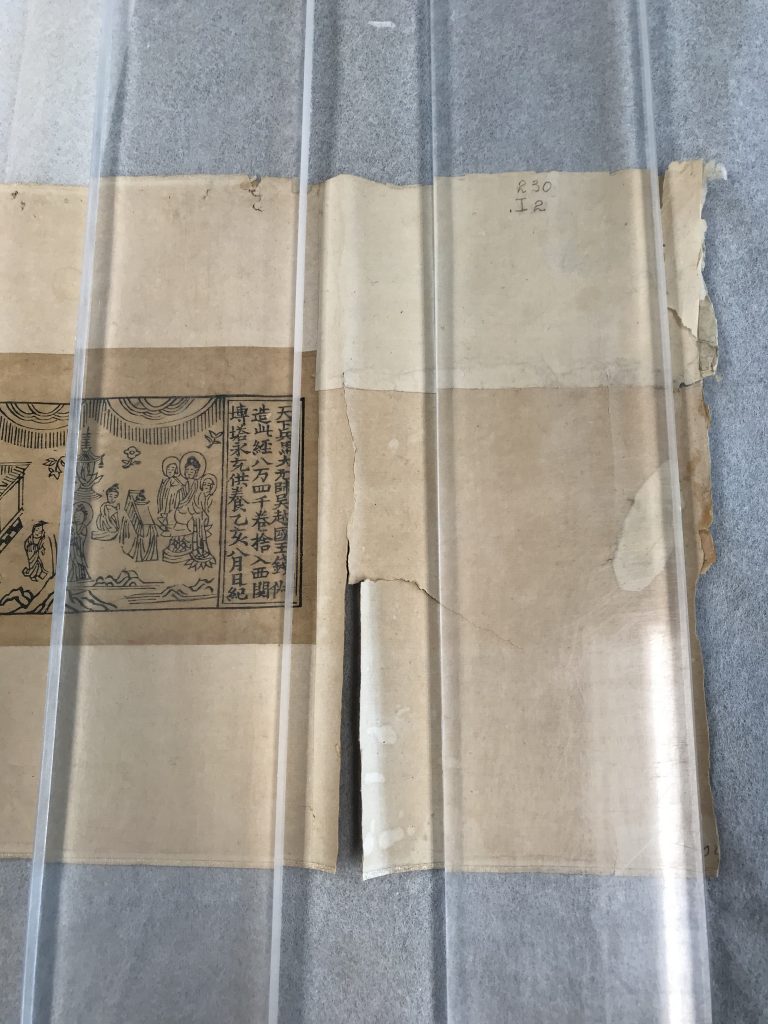

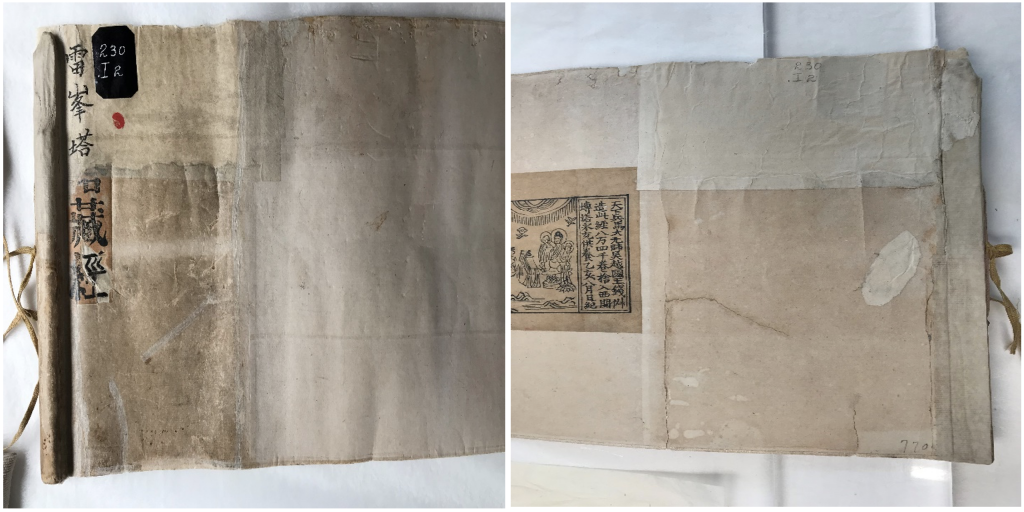

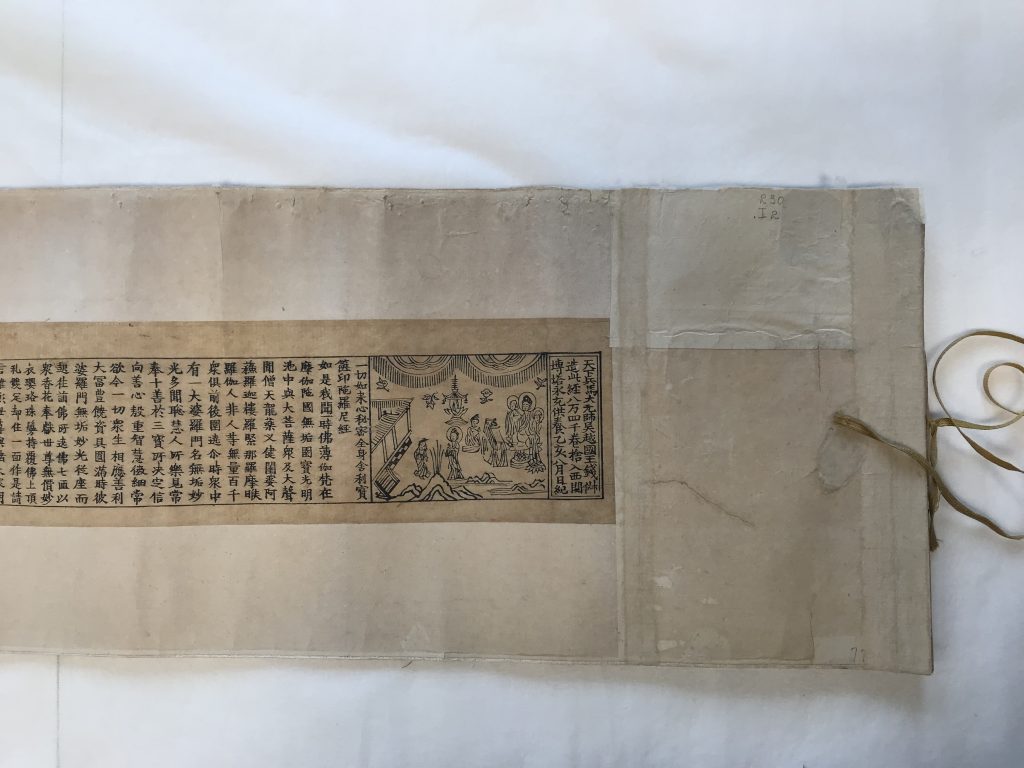

In preparation for a Chinese Object Study Workshop hosted by the National Museum of Asian Art (NMAA) in late August, I selected a sutra in the Freer and Sackler Library to illustrate the evolution in printing of Chinese books. The rolled sutra is Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) and was printed in 975 CE, likely making it the oldest printed item in our library collections. It is 6.35 feet long and 1.2 feet wide and mounted on Xuan paper (rice paper). The sutra was originally stored in a brick in the Thunder Peak Pagoda in Hangzhou, China and was found in 1924 when the pagoda collapsed during a storm.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) before conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) before conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

However, the sutra when it entered the library’s collection was in dire condition and urgently needed some conservation treatment to stabilize its condition and repair torn parts. NMAA’s East Asian paper conservator, Xiangmei Gu, voluntarily took on the task and did an excellent job to retore the sutra to its glory and made it possible to show it for the workshop.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) after conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) after conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

The following series of pictures demonstrate the process of conservation carried out at NMAA’s Department of Scientific Research.

Before treatment:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) before conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) before conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Weights were deployed for preparation:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Rod was reattached:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Tears were patched:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Damp towels and Gore-Tex were used in preparation for flattening:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Weights were applied again in the flattening process:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) during conservation. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

The scroll after treatment:

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) after conservation treatment. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

Baoqieyin Dharani sutra (宝箧印陀罗尼经) after conservation treatment. Photo by Xiangmei Gu.

The library is grateful for Xiangmei Gu’s skillful conservation of this very important historical document. Without her work, this sutra in our collection would have remained on a shelf, too fragile to open.

It has been a long journey from the ruins of Hangzhou’s Buddhist pagoda to our library collection. The sutra’s journey to recovery from its devastated condition could only have been realized with the care of an expert whose training took many years.

Introducing the Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative

During American Archives Month, we’re highlighting the work of our Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative in a series of posts. This is the first post in the series.

Smithsonian Institution Archives, and now the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, have been working diligently for the past 7+ years to gather information, leverage existing resources, and demonstrate the need for holistic support for a new, pan-institutional initiative to care for and provide access to our audio, video, and film collections. I present to you now, the great unveiling of <drumroll, please>: The Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI)!

While this is an unveiling of sorts, I need to also acknowledge that my colleagues across the Smithsonian have been working for decades to preserve, digitize, and provide access to our diverse audiovisual collections. However, as many of us experience, resources ebb and flow throughout the years and priorities change—this greatly affects our ability to properly care for collections. One of the primary goals of AVMPI is to pool our resources and expertise into one central resource that focuses on preservation for all Smithsonian units.

¼-inch open reel audio tape being digitized on an Ampex ATR-2 deck at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. Image courtesy of Emily Niekrasz.

¼-inch open reel audio tape being digitized on an Ampex ATR-2 deck at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. Image courtesy of Emily Niekrasz.

This initiative is supported by experts from around the Smithsonian, from archivists and conservators to directors and advancement staff. Currently, there are three structured teams supporting and overseeing AVMPI activities. First, our Advisory Committee consists of senior-level leaders who act as a link between AVMPI and the larger Smithsonian community to increase visibility, provide guidance for specific issues and challenges, and convey needs and advocate for resources to support the long-term goals of AVMPI. Second, our Task Force consists of subject matter experts who have direct input on AVMPI tasks and goals. They help to define workflows, design workspaces, and provide collection information to support preservation and accessibility. Lastly, our core team consists of seven new positions that will focus solely on AVMPI and our pan-institutional needs. We’ve already hired two of those core team members—Siobhan Hagan as our AVMPI Coordinator and Walter Forsberg as our Curator of Audiovisual Media. Make sure you check out their blog posts coming in October!

As it did for many, the pandemic affected our proposed timeline in ways we couldn’t have imagined. While it gave us time to reflect and make well-calculated decisions about goals, workflows, and resources from the safety of our homes, it did not give us the time to digitize our collections on-site. However, I’m happy to say that 2023 will be different! Here’s a peek at some of our plans for the next year:

- Reimagining existing audiovisual preservation labs at the Smithsonian. AVMPI is working closely with other Smithsonian units to breathe new life into their current audiovisual digitization set-ups. Whether it’s adding equipment, performing maintenance, reworking rack set-ups (or a combination of all), we plan to station our new preservation specialists at these locations to begin digitizing collections.

- Executing grant-funded projects. AVMPI has received funding from the American Women’s History Initiative to support the digitization, and caption services for remarkable and unique audio, video, and film media collections from six Smithsonian units. The project, entitled Witnessing Working Women: Digitizing SI’s Primary Source Audiovisual Recordings, will unlock institutional audiovisual collections chronicling stories of women within the American workforce.

- Developing innovative and nimble workflows. Standardizing digital and physical workflows across the Smithsonian will be no easy feat! While all units do share some of the same systems, such as our digital asset management system (DAMS), each unit also has their own unique way of cataloging, treating, and providing access to their audiovisual assets. AVMPI will look to build new, cohesive workflows that are supported by those existing systems and resources.

- Augmenting accessibility for audiovisual media and Smithsonian streaming content. AVMPI will foreground ‘best practices’ in accessibility for digital audiovisual assets through a ‘lead-by-example’ philosophy. We will prioritize captioning, transcription, and audio description to reach our hearing- and visually-impaired audiences, and we will work to develop clear guidelines for meeting accessibility standards required by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

- Creating authentic engagement opportunities that highlight SI pan-institutional audiovisual collections. The Smithsonian’s audio, video, and film collections represent the diversity of our world. However, the meaningful connections that exist between our individual unit collections have not been fully explored. In the coming year, AVMPI will not only increase online access to digitized collections but will build online exhibitions that explore these relationships. In addition, we hope to host or participate in several in-person screenings and receptions that will reach new audiences. Stay tuned for details!

- Increasing staffing. We’re planning on hiring four more team members to support our goals—an audio preservation specialist, a video preservation specialist, and two media collections specialists.

As you can see, AVMPI has quite a lot of work to do, but we’re encouraged by the continued support of leadership and colleagues across the Smithsonian. I, personally, am ecstatic to have Walter and Siobhan onboard and can’t wait to see what this next year brings!

For more information, please visit: s.si.edu/AVPreservation

Smithsonian Collaborates With Prestel to Publish “Wild Flowers of North America”

What does it take to paint a wildflower that blooms for a single day in a deep forest? For Mary Vaux Walcott, it involved spending up to seventeen hours a day out of doors with her paintbox to capture the shape, movement, and colors of delicate petals and leaves. Originally published in 1925 as North American Wild Flowers in five volumes, Walcott’s sketches brought the diversity and beauty of native plants to the general public. Working with the publisher Prestel, we have selected some of the most stunning flower portraits from our own copies of Walcott’s original work and compiled them in this single volume. This new book, Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott , also features biographical text written by institutional historian Pamela Henson.

Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott (2022).

Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott (2022).

Walcott’s technique involved precise attention to detail, color, light, and perspective. Her art can also be appreciated as the work of a woman scientist battling the prejudices against her gender of the day. She was an intrepid explorer and skilled geologist at a time when women’s accomplishments were often overlooked or misattributed. She also had incredibly strong ties to the Smithsonian — North American Wild Flowers was first published as a fundraiser for the Institution.

Left: Portrait of Mary Vaux Walcott, SIA RU000095 [SIA_000095_B27F_019], Smithsonian Institution Archives. Right: “Carolina Jessamine”, Plate 220, North American Wild Flowers (1925).Inspirational, informative, and a pleasure for the eyes, this bouquet of Walcott’s work is a lasting treasure of botanic and scientific artistry. Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott is now available from Prestel and book retailers worldwide.