Libraries' Blog

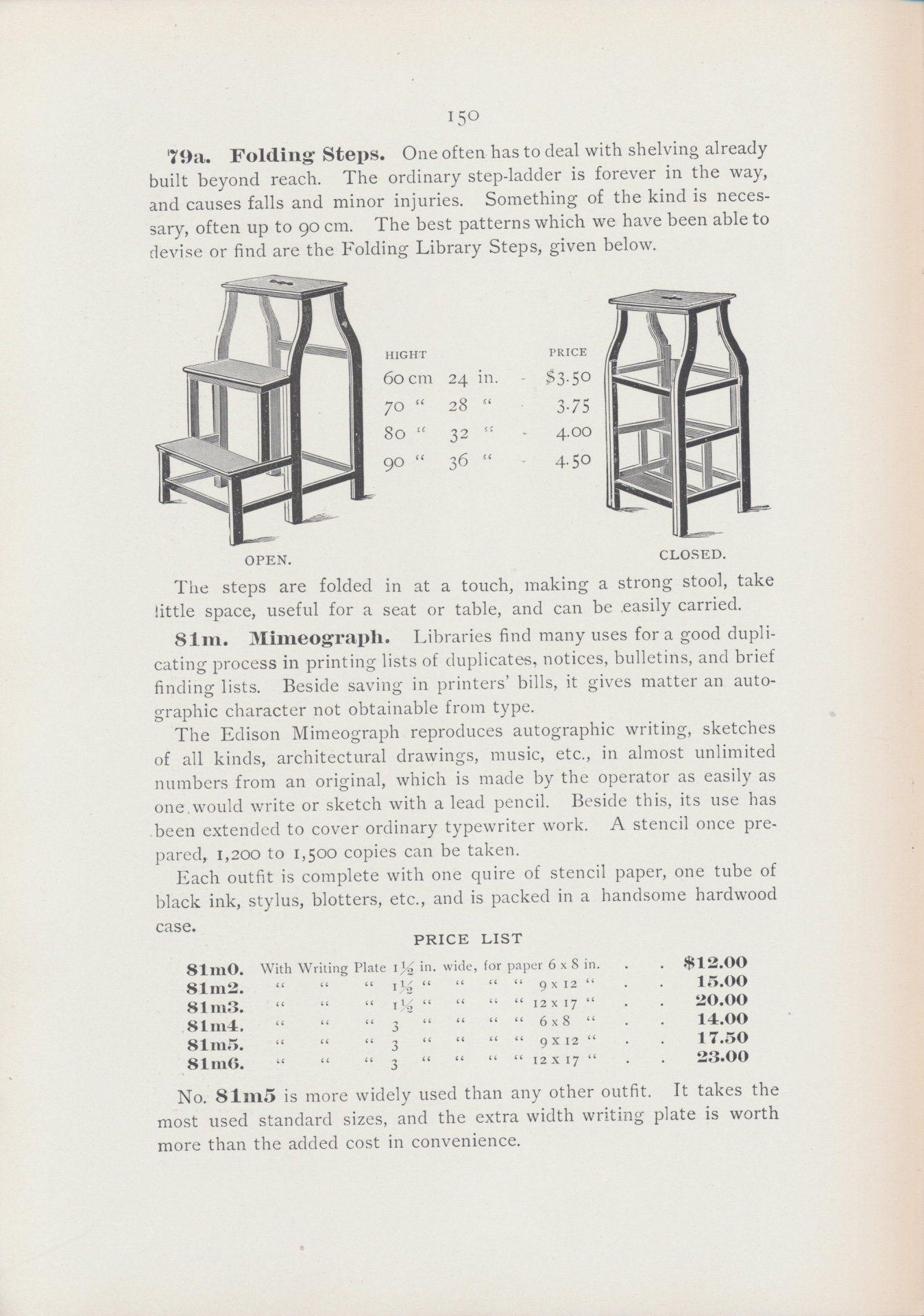

Packing for a Vacation in 1907

Imagine it is the early 20th Century and you are packing for summer vacation. What did your luggage look like? Did you pack your clothes in a trunk? What were your options? Today we are familiar with rolling luggage on wheels, but trunks and suitcases over a hundred years ago looked quite different.

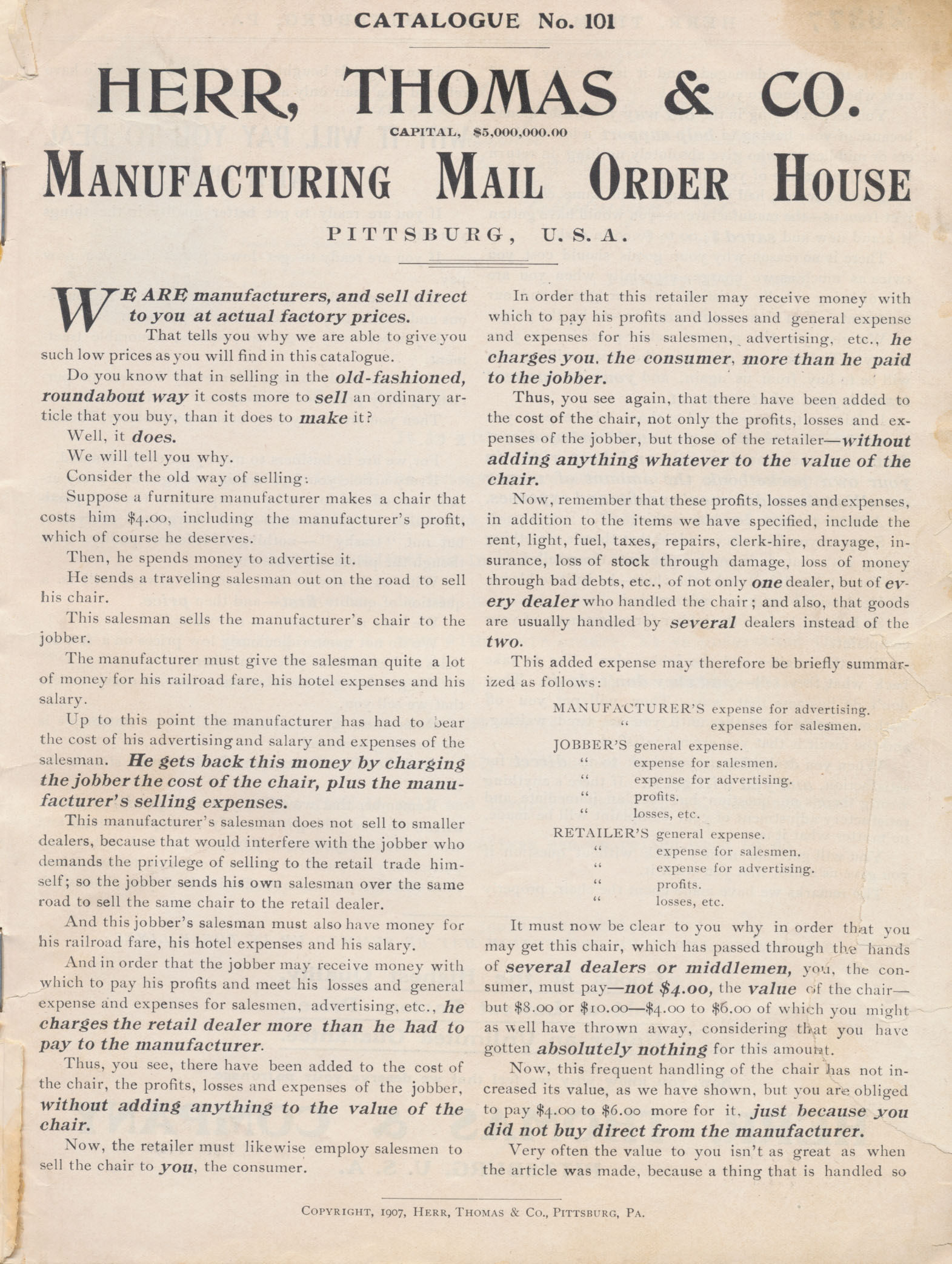

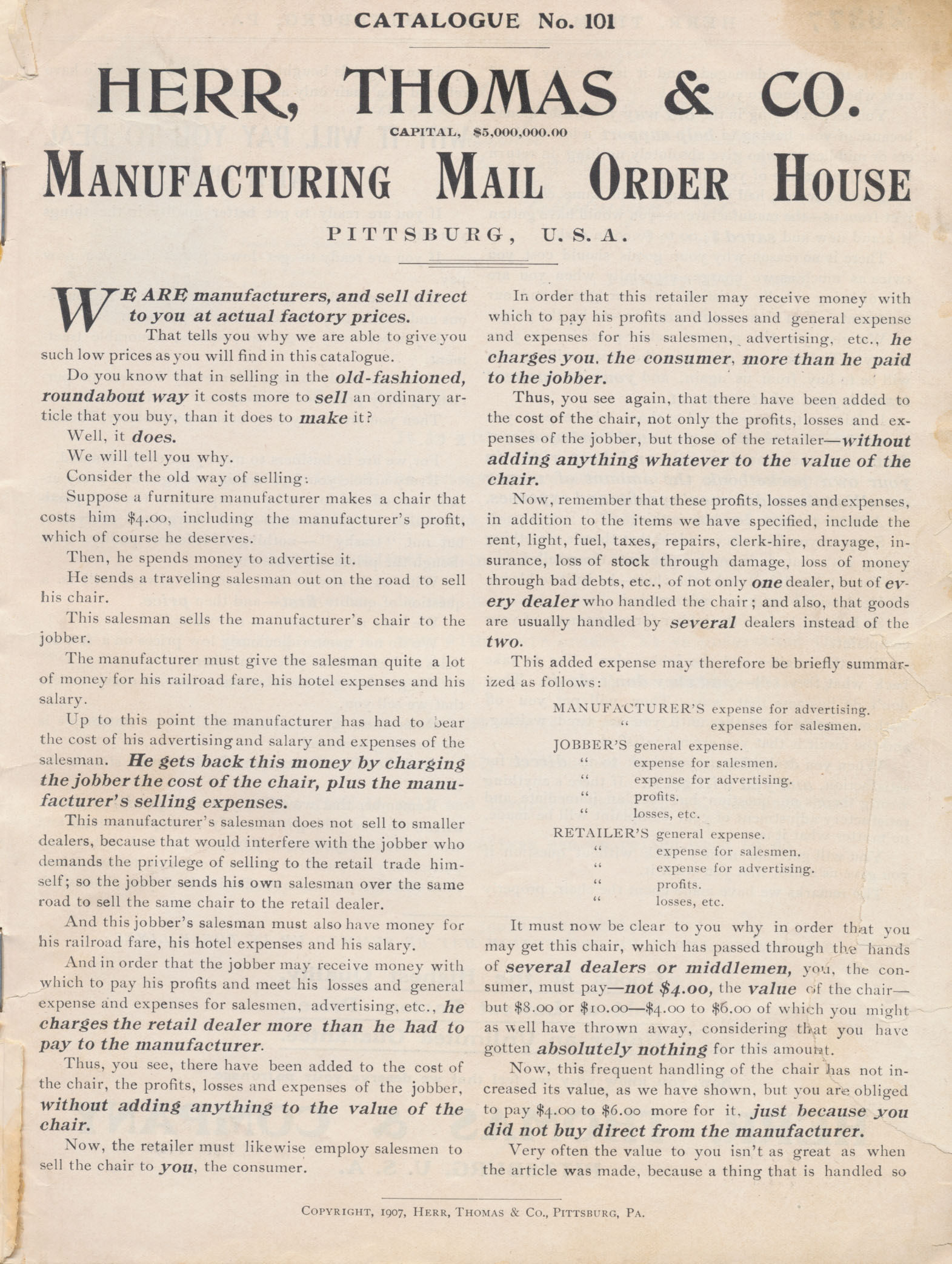

Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. provides a peek into the past, specifically the year 1907. Flipping through this trade catalog, we will learn about the types of luggage available in that time period. A few other items illustrated in this catalog might also have made a vacation fun and memorable.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Packing is not always easy. What do you bring and what do you leave behind? Do you really need that extra sweater? Maybe it would be easier if you just brought your entire dresser along. That might not be quite possible, but in 1907 there was a piece of luggage called the Dresser Trunk (below, top left). It was described as “embodying the latest ideas of travel comfort” and “combining the uses of both a trunk and dresser.” The Dresser Trunk was composed of three-ply veneer bass wood, covered with canvas, painted, varnished, lined with cloth, and the frame was reinforced with hard wood strips. It also had hand riveted wrought iron clamps, corners, hinges, and fastenings.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.Packing is not always easy. What do you bring and what do you leave behind? Do you really need that extra sweater? Maybe it would be easier if you just brought your entire dresser along. That might not be quite possible, but in 1907 there was a piece of luggage called the Dresser Trunk (below, top left). It was described as “embodying the latest ideas of travel comfort” and “combining the uses of both a trunk and dresser.” The Dresser Trunk was composed of three-ply veneer bass wood, covered with canvas, painted, varnished, lined with cloth, and the frame was reinforced with hard wood strips. It also had hand riveted wrought iron clamps, corners, hinges, and fastenings.

A convenient feature was its ability to open on the side. Instead of lifting everything on top to get to something on the bottom, the drawers made it possible to go directly to the location of a specific item without interfering with the contents of the rest of the trunk. In other words, the Dresser Trunk functioned just like a dresser with drawers. There were three drawers, one large and two of medium size. The large drawer included two compartments. There were also other compartments beneath the large drawer and in the lid. Wondering where that mirror was located? Inside the lid was a French bevel mirror. A Yale lock safely secured belongings inside the trunk. The Dresser Trunk measured 32 inches long, 21 inches wide, and 21 inches high with the lid closed or 42 inches high with the lid raised.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 74, Dresser Trunk, Suit Case, Leather Suit Case, Cabinet Bag, Trunk, Steamer Trunk, Hand Bag or Satchel.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 74, Dresser Trunk, Suit Case, Leather Suit Case, Cabinet Bag, Trunk, Steamer Trunk, Hand Bag or Satchel.

Maybe bringing a Dresser Trunk is not quite what you had in mind for a vacation. In that case, Herr, Thomas & Co. also offered other trunks, such as the Steamer Trunk (above, middle right). Its interior was composed of a tray divided into a large and small compartment with four additional large compartments beneath the tray. It also provided security by using a Yale lock.

Other options included a simple suitcase, such as the ones shown above (middle left). The Suit Case advertised for $2.85 in this 1907 catalog included a cloth-lined interior, leather handle, and lock. A Hand Bag or Satchel (above, bottom right) and Cabinet Bag (above, bottom left) are also illustrated in the luggage section of this catalog.

Besides clothing, what other items might you have packed for a vacation in 1907? Perhaps, a tourist brought along the Premo Folding Film Camera (below, middle left). According to Catalogue No. 101 (1907), this particular camera is described as “a very compact outfit that is especially adapted to tourists use” because once it was folded, it was small enough to fit in a pocket. It had a capacity of 12 exposures and was capable of producing photos measuring 3 ¾ x 4 ¼ inches.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 73, Shaving Set, Shaving Mug and Brush, Premo Folding Film Camera, Cyclone Magazine Camera, Lady’s Opera Glasses, Folding Opera Glasses, Field Glasses.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 73, Shaving Set, Shaving Mug and Brush, Premo Folding Film Camera, Cyclone Magazine Camera, Lady’s Opera Glasses, Folding Opera Glasses, Field Glasses.

Perhaps an opera might have found its way onto a 1907 vacation itinerary. Opera glasses such as the Lady’s Opera Glasses shown above (middle left) might have come in handy. It was fast and easy for theatre-goers to adjust the lenses to various distances while viewing the performance. To keep the opera glasses safe during transit, it came with a black leather satin lined case.

Some might have preferred the Folding Opera Glasses, also shown above (bottom left). Fitted with achromatic lenses, these opera glasses folded into a steel case measuring 4 x 3 x 5/8 inches. For safekeeping, its small size made it easy to fit into a pocket or wrist bag.

Perhaps, a theatre-goer might have stored these Folding Opera Glasses in a bag such as the Lady’s Wrist Bag (below, top left). Herr, Thomas & Co. also sold other items including a hand bag, wallets, lady’s pocket book, and lady’s chatelaine bag, as illustrated below.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 75, Lady’s Wrist Bag, Wrist Bag, Grain Leather Bill Wallet, Hand Bag, Lady’s Pocket Book, Strap Wallet, Lady’s Chatelaine Bag, Ormulu Gold Clock, Regulator Clock.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 75, Lady’s Wrist Bag, Wrist Bag, Grain Leather Bill Wallet, Hand Bag, Lady’s Pocket Book, Strap Wallet, Lady’s Chatelaine Bag, Ormulu Gold Clock, Regulator Clock.

Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Assessing File Format Risk for Born-Digital Preservation Planning

This post originally appeared on the Smithsonian Institution Archives’ blog. Melissa Anderson’s internship was part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ 50th Anniversary Internship program, with funding provided by the Secretary of the Smithsonian and the Smithsonian National Board.

When I entered the MLIS program at the University of Alabama School of Library and Information Studies in 2018 and became interested in digital libraries, I was surprised to learn that the information we create and store digitally is just as, and in some cases even more, fragile than unstable media or paper. Physical damage, deterioration of digital storage media, and the technological complexity and dependency of electronic records make them uniquely vulnerable to loss, corruption, and alteration. As keepers of records with historical, cultural, and legal value, archival repositories have a responsibility to identify at-risk digital objects and take preemptive action to preserve them in a format that is accessible to the broadest possible public for the longest possible time. As a Smithsonian Libraries and Archives 50th Anniversary intern in born-digital collections, I’m learning how to do just that.

At present, more than half of the Smithsonian Institution Archives’ annual accessions contain born-digital materials, most of which are acquired in mixed collections alongside print and analog media. To document and serve the Institution, the Archives collects documents, spreadsheets, images, audiovisual (AV) material, email, databases, designs, data sets, software, websites, and social media content. These electronic records span more than 40 years and are stored in a variety of media formats, some of which require urgent preservation to avoid information loss.

Gif slideshow of Digital Collections information.

Gif slideshow of Digital Collections information.

The Archives’ employs a multi-pronged born-digital preservation strategy that follows professional standards and best practices including the OAIS Reference Model and trustworthy digital repositories. The three prongs are: bit-level preservation, migration of at-risk files to stable preservation formats, and emulation for access to records locked in obsolete formats. The first strategy creates an exact copy of a file’s content information and data structure and is applied to all digital objects on accession. Having two (or more) identical copies of every file and storing them in different locations mitigates the risk of loss due to media, system, or human failure and disasters like fire and flooding, but possession does not automatically equal access. Our ability to even open and view a file during processing depends on hardware and software that can read and render it.

Obsolescence affects both the machines and the software we use to create, store, and access digital files. Advancements in power, speed, efficiency, and cost lead to rapid obsolescence of computer hardware. The introduction and adoption of new hardware also leads to new and improved software, which eventually makes older software and the file formats it supported obsolete as well. The wide use of proprietary file formats has created a situation in which only the program that created the file—or, even more specifically, a particular version of that program—can be used to open that file.

Sometimes only the information (i.e written text) contained in a file is important, but often we need to preserve the appearance and function of files as well to ensure that evidential and use value is maintained. Take, for example, a newsletter created using Adobe InDesign 1.0 (circa 1999) and selected for a digital exhibition commemorating the Smithsonian’s 175th anniversary. If we’re only able to render the text of that document but not the images, layout, colors, or fonts, we would have only a part of the newsletter the original user experienced. This is where our second and third prongs—migration and emulation—come into play.

Migration involves moving a file from an at-risk or obsolescent format to a format digital archivists agree is more stable. Despite dependence on hardware and software, migration is an effective way to preserve digital objects and make them accessible, so long as it’s done promptly and as needed to keep up with technology. But it requires archivists to verify fixity, which assures that a copied or converted file hasn’t been altered from the original. Digital files can be changed or corrupted accidentally during preservation events, through human error, or maliciously by actors who wish to alter or destroy records. Checksums enable archvists to validate the authenticity of records, which is essential for maintaining public confidence in the trustworthiness of repositories. If the hash of a copied file matches the hash of the original, archivists can be confident the record has been reproduced exactly.

When files can’t be migrated, emulation provides another mode of preservation and access. This method uses programming to emulate the appearance and function of obsolescent computing technologies—one can, for instance, turn a Raspberry Pi into an original Nintendo gaming system. But the kind of emulation needed to preserve both the information content and appearance of digital records is much more complicated and expensive. A well-known and early use of emulation was undertaken at Emory University’s Rose Library. In 2009, when I was a third-year doctoral student in American Studies there, my digital humanties friends were all excited about a digital archives technology that convincingly replicated Salman Rushdie’s Power Macintosh 5400. Emory’s case study became an early model for successful digital preservation, but their innovation was supported by a resource-rich institution that invests heavily in its archives and special collections libraries.

Ten years later, when I entered library school, I understood why my Emory classmates had been so excited; migration and emulation enable us to preserve and provide access to electronic records at scale.Today, we’re challenged to develop preservation policies and workflows that include strategic risk assessment. The Archives’ digital preservation team is performing a detailed risk analysis of the born digital holdings in our collections.This process starts at ingestion by identifying and validating the format type of each file using DROID and JHOVE, as well the PRONOM technical registry. Digital archivist Lynda Schmitz Fuhrig or another team member reviews this and other administrative metadata. All the administrative information about the born digital content in an accession is gathered in the Archives’ DArcInfo (Digital Archive Information System) database.

Screenshot of DArcInfo query results showing format type and count by accession for born-digital holdings.

Screenshot of DArcInfo query results showing format type and count by accession for born-digital holdings.

By querying this database, we can determine and document our preservation backlog (how many assets we hold that do not yet have a preservation master file), giving us the scope of our to-do list. We can also inventory the format status of our digital holdings (including format type and version) and assess storage media (type, stability, and condition). We intend to use this information to identify the range of formats and how many files in each format we hold by accession. From there, we will draft a plan for targeting the most valuable and at-risk digital objects in our collections so that we can preserve them in accessible formats before they’re lost.

Exploring Bias and Library of Congress Subject Headings

I am currently wrapping up my first year as an MLS student at Emporia State University, with a concentration in archives. A sense of curiosity, a love of learning, and a passion for research led me to libraries and archives as a career. I am drawn to the idea of working for universal access to information and knowledge, and I intend to work to disrupt systems of oppression in our institutions. In Spring of 2021, I took a required course in my program that introduces students to basic concepts in cataloging and classification. While I had already chosen a concentration that fills most of my elective credits, I wanted to learn more about cataloging. The cataloging project, part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ 50th Anniversary Internship program, was the perfect opportunity to further develop my knowledge of descriptive work, while incorporating ethics of social justice.

For this project, I had the pleasure of working with Heidy Berthoud, Head of Resource Description, and Amanda Landis, Library Technician. We started with materials relating to ideas of diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) within Smithsonian Libraries and Archives library collections and examined the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) being used for those materials in library catalogs. We then considered where there were gaps in the assigned headings which did not fully convey the meaning of these works, or where subject headings being used were inappropriate or outdated. We would then draft proposals for new subject headings, with the goal of improving accuracy and inclusivity within LCSH.

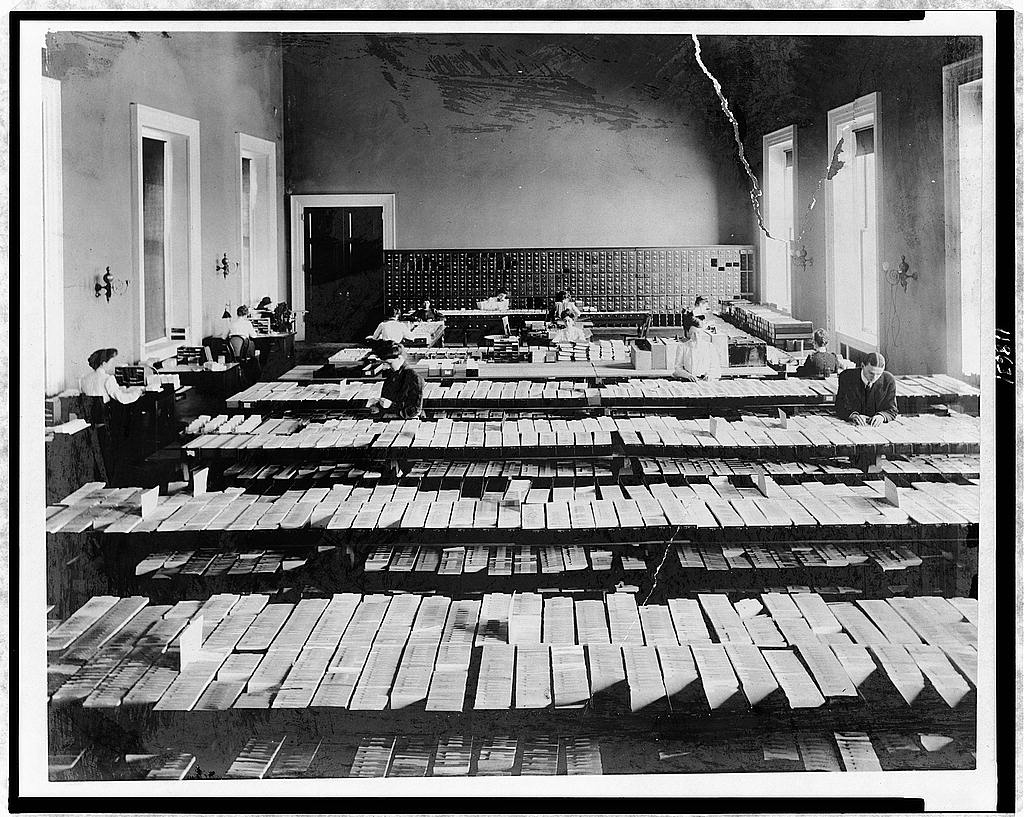

People working in Card Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [Between 1900 and 1920] [Photograph]. Library of Congress.As intern for this project, I conducted research needed to justify proposals and provided an additional critical eye as we searched for issues. I took particular interest in issues of gender and sexuality within LCSH, performing research to determine the relationships between terms as the hierarchy of LCSH exists at present. This led me to discover that a common sexual orientation, pansexuality, is currently absent from LCSH. I performed the research to draft a proposal for pansexuality as a new heading. I also performed research to support a change in the heading “sexual minority culture,” hoping to update it to “queer culture” (this heading exists in addition to “gay culture” and “lesbian culture”).

People working in Card Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [Between 1900 and 1920] [Photograph]. Library of Congress.As intern for this project, I conducted research needed to justify proposals and provided an additional critical eye as we searched for issues. I took particular interest in issues of gender and sexuality within LCSH, performing research to determine the relationships between terms as the hierarchy of LCSH exists at present. This led me to discover that a common sexual orientation, pansexuality, is currently absent from LCSH. I performed the research to draft a proposal for pansexuality as a new heading. I also performed research to support a change in the heading “sexual minority culture,” hoping to update it to “queer culture” (this heading exists in addition to “gay culture” and “lesbian culture”).

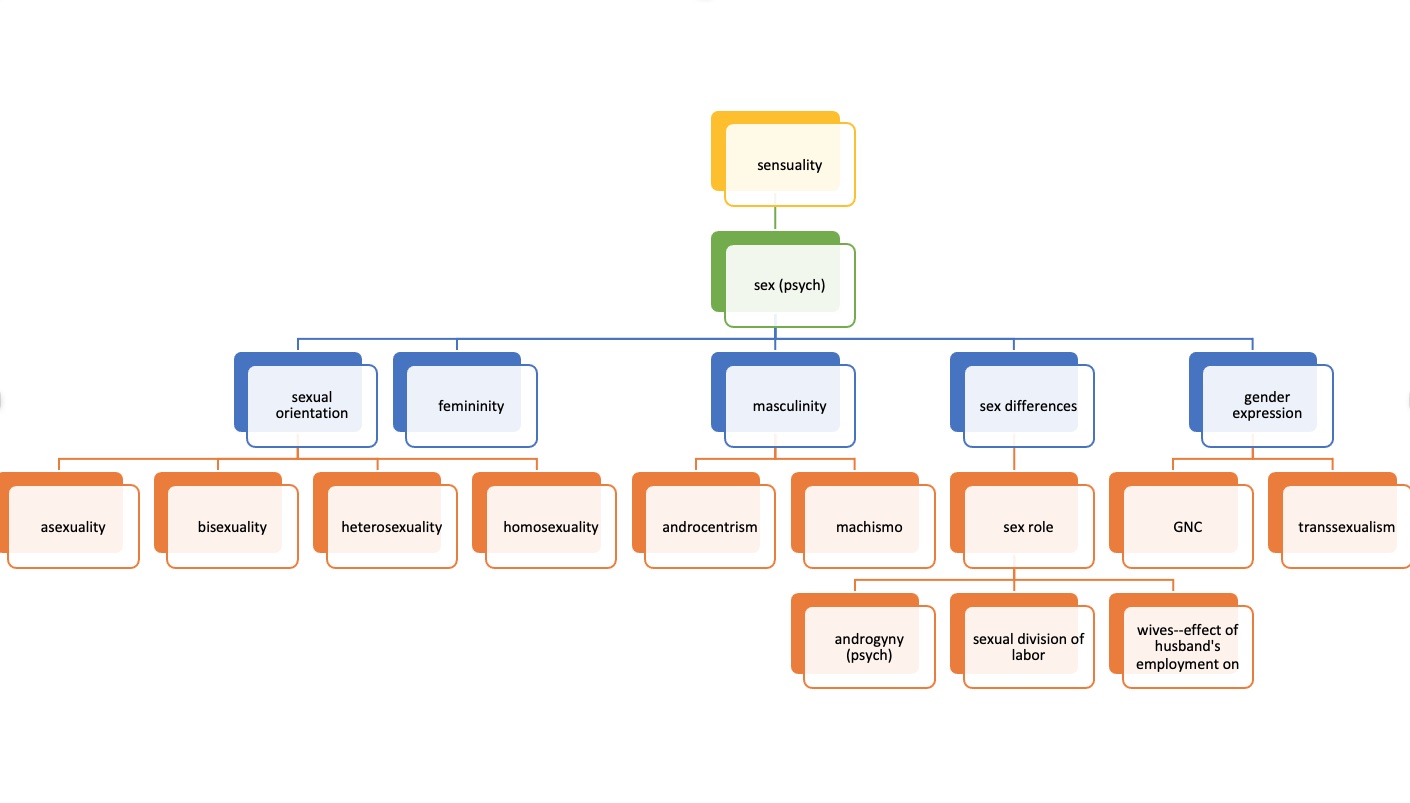

Mapping sexuality terms as present in LCSH [screenshot]. River Freemont.Through this project, I learned a lot about the process and politics of proposing headings. There are an extensive number of complicated rules for constructing proposals, but it is also important to be mindful of how LC prefers things to be done, even if they are not requirements. Consistency within LCSH is a common factor in rejections, as well as the impact a change would have on the larger system. It can take over two months to receive a ruling on your proposal. Heidy even arranged for us to attend an editorial meeting of the LC Policy, Training, and Cooperative Programs Division (PTCP), where decisions are made about new headings or revisions to headings.

Mapping sexuality terms as present in LCSH [screenshot]. River Freemont.Through this project, I learned a lot about the process and politics of proposing headings. There are an extensive number of complicated rules for constructing proposals, but it is also important to be mindful of how LC prefers things to be done, even if they are not requirements. Consistency within LCSH is a common factor in rejections, as well as the impact a change would have on the larger system. It can take over two months to receive a ruling on your proposal. Heidy even arranged for us to attend an editorial meeting of the LC Policy, Training, and Cooperative Programs Division (PTCP), where decisions are made about new headings or revisions to headings.

It is important to consider that headings are approved based on works being cataloged, not anticipation of some future need for a heading. So, an important part of writing proposals is to provide literary warrant – justifications for headings that consist of published works where the term is being used – which shows the PTCP that experts in the field agree that your heading is the preferred term. Something this brought up for me is the validity of lived experience. How can we privilege the voices of those whose lives are affected by the language used to describe them? Potential solutions to this issue that I found were choosing sources that interviewed subjects or contained personal anecdotes, as well as considering the positionality of the author or the publication.

There are issues with access to this process. In order to perform this work, we really need to have access to tools such as RDA Toolkit, OCLC Connexion, Classification Web, or Cataloger’s Desktop. These are costly tools that not everyone wishing to do this work will have access to through their institution. There is an overrepresentation of university, research, and national libraries, as well as vendors, in the decision-making process. Conversely, there is a lack of representation from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), public and school libraries, and international libraries. During our work on this project, Heidy was able to consult a colleague with insider knowledge, but not everyone will have that kind of connection.

Heidy also introduced me to Cataloging Lab, a project started by Violet Fox. It is a website “designed so that people who are familiar with LCSH and experienced with the…proposal process can assist those who want to do the research to make changes”. I was inspired by this project because it is increasing access to the process, facilitating collaboration, and sharing knowledge in order to make positive changes in a difficult system. Anyone can join and post their proposals, receive knowledgeable input, and assist others with research.

I found the iterative nature of the process was a challenge with this project. It was necessary to keep in mind that we might not see immediate results from our efforts, but we are contributing to change, and others can come along and build off our work. Another significant challenge was overcoming my inclination toward introversion, and developing confidence in myself as a professional. It certainly paid off in the end, however, as the connections I made were my favorite part of this experience.

I particularly enjoyed attending Smithsonian Library and Archives meetings, such as the National Museum of Natural History’s Collections Task Force. I loved learning about different projects underway at the Smithsonian and learning about what librarians do for the Smithsonian community. Heidy facilitated a lot of conversations with different folks around the Smithsonian, some librarians, some not. These conversations helped to inspire me, give me direction for my education and future career, and increase my confidence as an emerging professional. I loved being a part of the Smithsonian community. The people I met were so kind and welcoming, and I especially enjoyed working with Heidy and Amanda.

River Freemont’s internship was part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ 50th Anniversary Internship program, with funding provided by the Secretary of the Smithsonian and the Smithsonian National Board.

Stewards of the Hungerford Deed

When the Smithsonian Institution was founded “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge,” it was difficult to know how impactful this mission would still be 175 years on. To this day, the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives strives to further this goal, sharing our knowledge to make discoveries and expand our understanding together with you, our community of supporters. The Hungerford Deed, which quickly became a treasure of our collections, exemplifies this work, as does the special opportunity to become a close supporter of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives by joining the Stewards of the Hungerford Deed. Read on to learn about how the Hungerford Deed illuminates the Smithsonian’s founding, and the impact you can make as a Steward.

The signature of Elizabeth Macie, James Smithson’s mother, on the Hungerford Deed, 1787, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 19-150.

The signature of Elizabeth Macie, James Smithson’s mother, on the Hungerford Deed, 1787, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 19-150.

The Deed is a 1787 property contract divvying up inherited lands between James Smithson’s mother and aunt. The insights shared by the Deed go beyond the legal decisions, illustrating a dramatic battle between the sisters and offering context via the family dynamics that shaped Smithson into the founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution. Like many archival discoveries, the Deed is an unpublished work that required ample preservation when it was anonymously donated to the Smithsonian in 2019. Preservation included carefully unfolding, stabilizing, and humidifying each parchment page so viewers can examine the pages, as interested parties might have three centuries ago. This process reveals and protects the original knowledge present in the Deed, contributing this knowledge to the collections that the Libraries and Archives safeguards as a resource for future generations.

The Hungerford Deed opened for the first time. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

The Hungerford Deed opened for the first time. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Sharing knowledge often leads to exciting discoveries in collaboration with other scholars and curious minds. The Libraries and Archives is excited to facilitate this exchange through a virtual exhibition launching on August 10, offering a deeper dive into the Deed. Visitors near and far will be able to virtually turn the pages of the Deed and explore for themselves, with highlights of interesting facts and context right on the page to enhance their understanding. The Deed offers a wellspring of new information pertaining to the history of women’s property rights, the British legal system, and Smithson’s genealogy, and we are excited to make this knowledge available to evolve understanding alongside researchers.

The first page of the Hungerford Deed, 1787, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 19-150.

The first page of the Hungerford Deed, 1787, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 19-150.

Our preservation, research, and outreach in connection to the Deed exemplifies just a few of the ways the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives protects and shares our collections. With scientific and cultural treasures ranging from oral histories to artists’ books, the Libraries and Archives is a resource where knowledge can be tested and expanded. Stewards of the Hungerford Deed champion this impact, ensuring this knowledge will continue to be safe and accessible. This special group will be celebrated in connection with the Deed and beyond, as the impact of these gifts reverberates through our crucial work.

The Archives conservation lab, where staff are working to preserve more of our treasures

The Archives conservation lab, where staff are working to preserve more of our treasures

You are invited to join our community of supporters, championing accessible educational resources, diverse collections, and critical preservation. Stewards are recognized beginning with a gift of $75, and benefits at a variety of giving levels include honoring Stewards on the virtual exhibition illuminating the Deed, a certificate recognizing your gift, and an exclusive invitation to view the Deed in person with fellow Stewards in the future. We are pleased to recognize donors with giving levels inspired by the real people behind the Hungerford Deed. Join their legacy today as a Steward in one of the following categories:

- Steward – $75 and more

- Keate Steward – $175 and more

- Walker Steward – $575 and more

- Macie Steward – $1,175 and more

- Smithson Steward – $5,175 and more

- Hungerford Steward – $10,175 and more

The Hungerford Deed illuminates the context for James Smithson’s commitment to knowledge, and the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives looks forward to re-committing and investing in this mission together with you.

Learn more about becoming a Steward of the Hungerford Deed!

P.S. Interested in learning more about the Deed and the upcoming virtual exhibition? Join us during our virtual program with conservator William Bennett on August 12! Attendees will take a closer look at the Deed and learn more about the significance of the discoveries it holds.

Vintage Furniture Finds from the Early 20th Century

Before online outlets and a certain Swedish superstore, imagine decorating and furnishing a new home in the early 20th Century. What did your furniture look like? What curtains or window hangings did you choose? How did you communicate with your neighbors? The Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library includes a few catalogs related to these very things.

One catalog is titled Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) by John Wanamaker. In previous blog posts, we learned about library pieces like armchairs and sofa beds as well as dining room furniture and tableware. Now, let’s explore a few more items from this catalog.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), front cover.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), front cover.

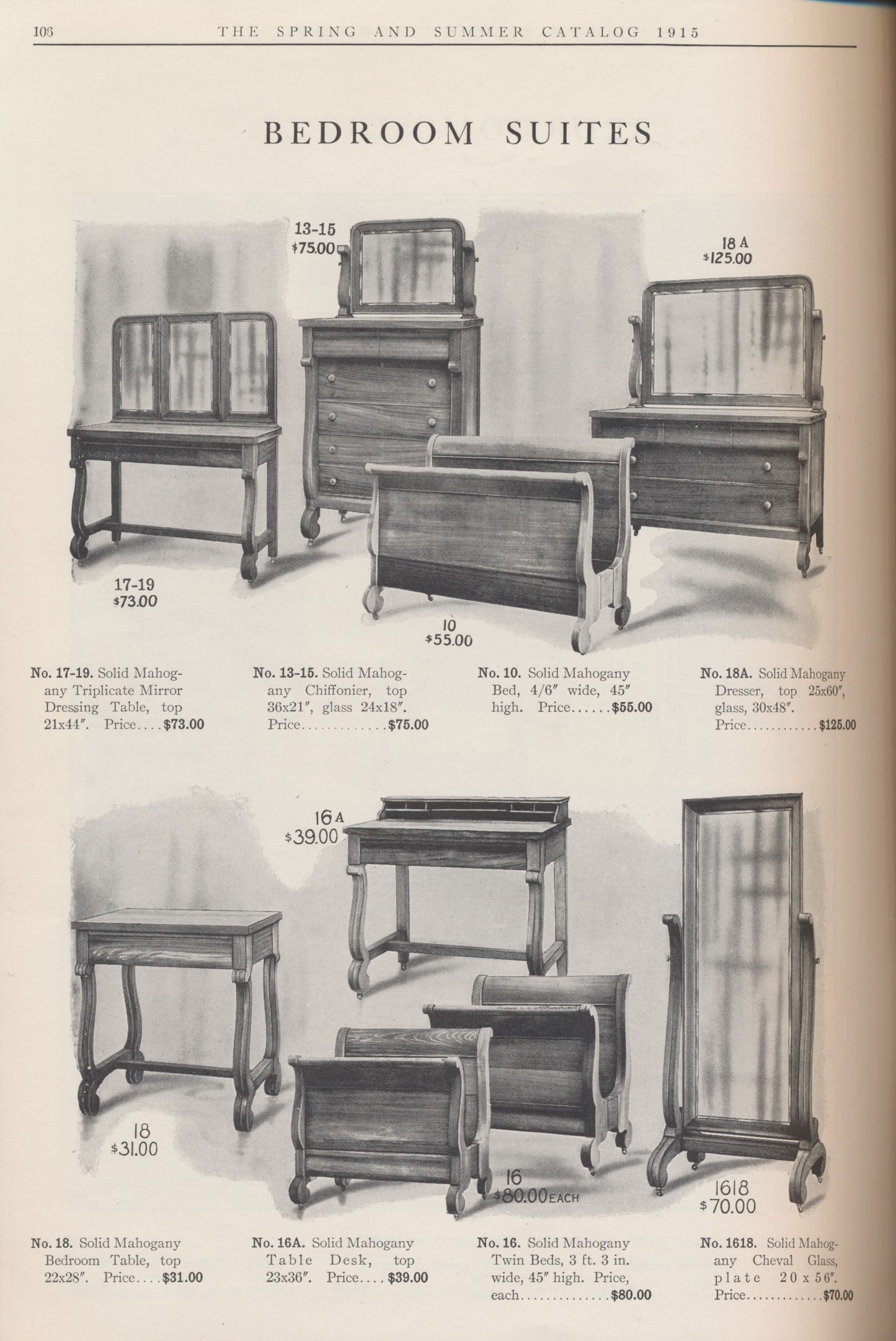

Several pages focus on bedroom furniture such as these Bedroom Suites manufactured from solid mahogany. The Bedroom Suite shown below included several pieces of furniture, but each piece was priced individually. This included bedframes (top and bottom, middle), dresser with glass (top right), chiffonier with glass (top, second from left), and dressing table (top, left). The dressing table came with a triplicate mirror, but those preparing for a special occasion might have preferred a tall or full-length mirror, such as the Cheval Glass (bottom right). Another piece in the suite was the Table Desk (bottom, middle). Perhaps it was used for corresponding with family and friends via letters. The top of the desk included small compartments to store stationery and supplies.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 106, Bedroom Suites (Dressing Table, Chiffonier, Bed, Dresser, Bedroom Table, Table Desk, Twin Beds, Cheval Glass).

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 106, Bedroom Suites (Dressing Table, Chiffonier, Bed, Dresser, Bedroom Table, Table Desk, Twin Beds, Cheval Glass).

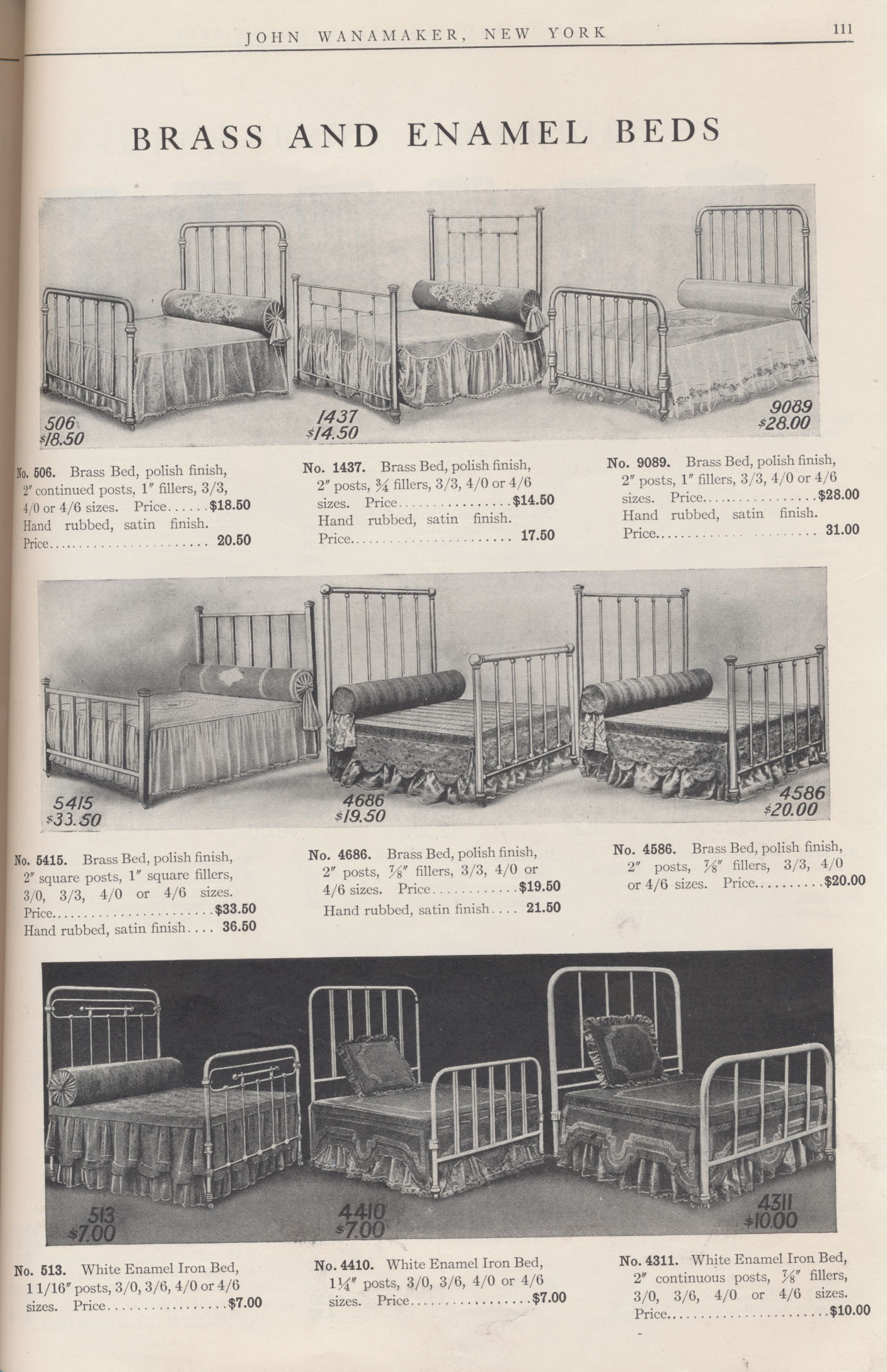

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 111, Brass and Enamel Beds.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 111, Brass and Enamel Beds.

Other choices included brass and enamel beds. The brass beds, shown above (top and middle rows), were available with a polished finish and most also had the option of a hand rubbed, satin finish. White Enamel Iron Beds are also illustrated above on the bottom row.

As for mattresses, one option was the Kurly-Kotton Elastic Felt Mattress (below, top middle). No space age foam or fancy fillings here – this elastic felt mattress was filled with cotton sheets laid by hand. The Single Border Spring (below, middle right) had 63 spirals and was compatible with wooden beds.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 119, Mattresses and Springs.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 119, Mattresses and Springs.

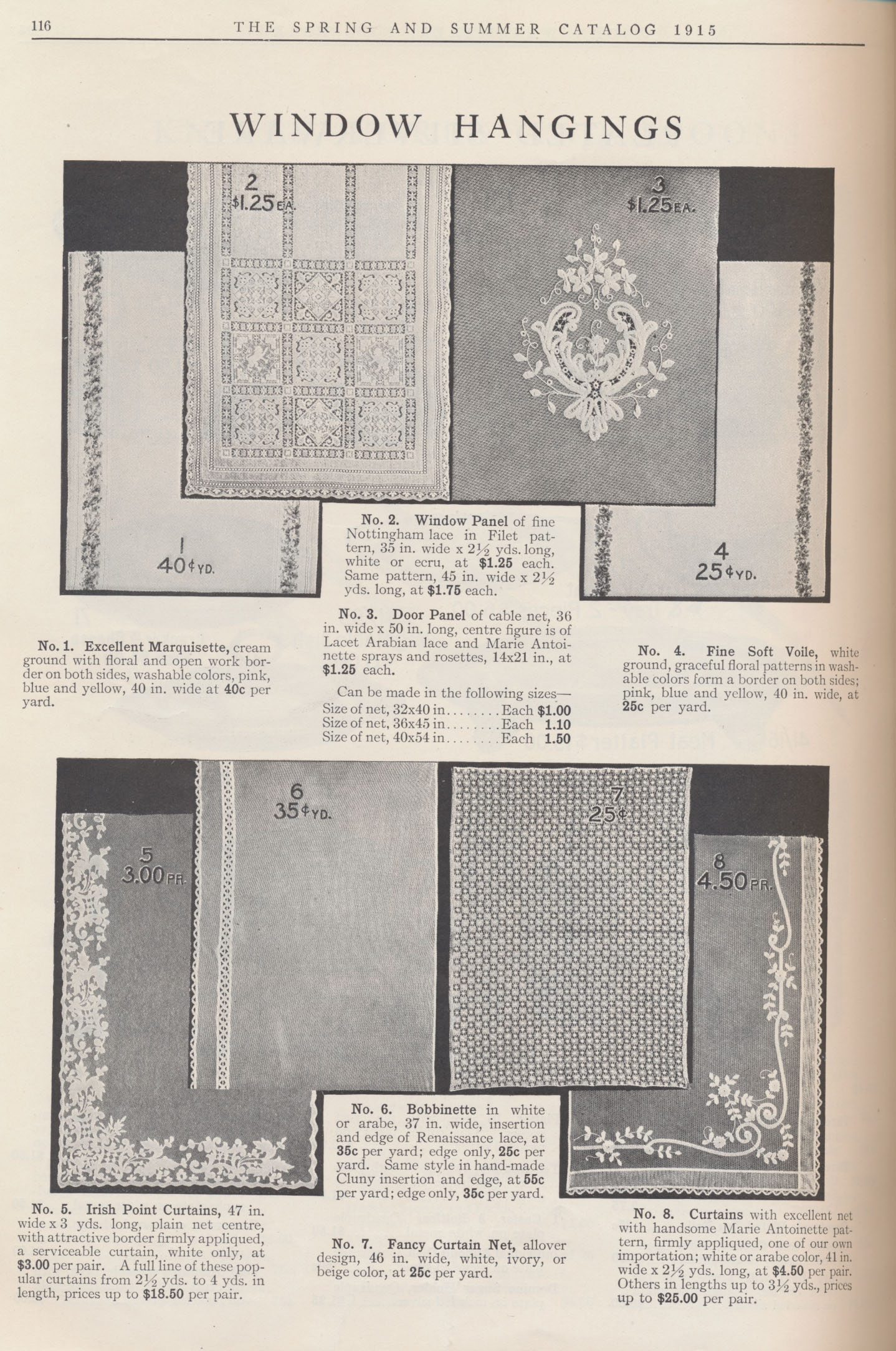

John Wanamaker also sold draperies and window hangings. Someone setting up their new home in 1915 could chose these Irish Point Curtains (below, bottom left). Measuring 47 inches wide and 3 yards long, these had a plain net center and decorative border. Other window hangings incorporated floral decorations, such as No. 4 Fine Soft Voile (below, top right). Described as having a “graceful floral pattern,” it was available in pink, blue, and yellow.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 116, Window Hangings.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 116, Window Hangings.

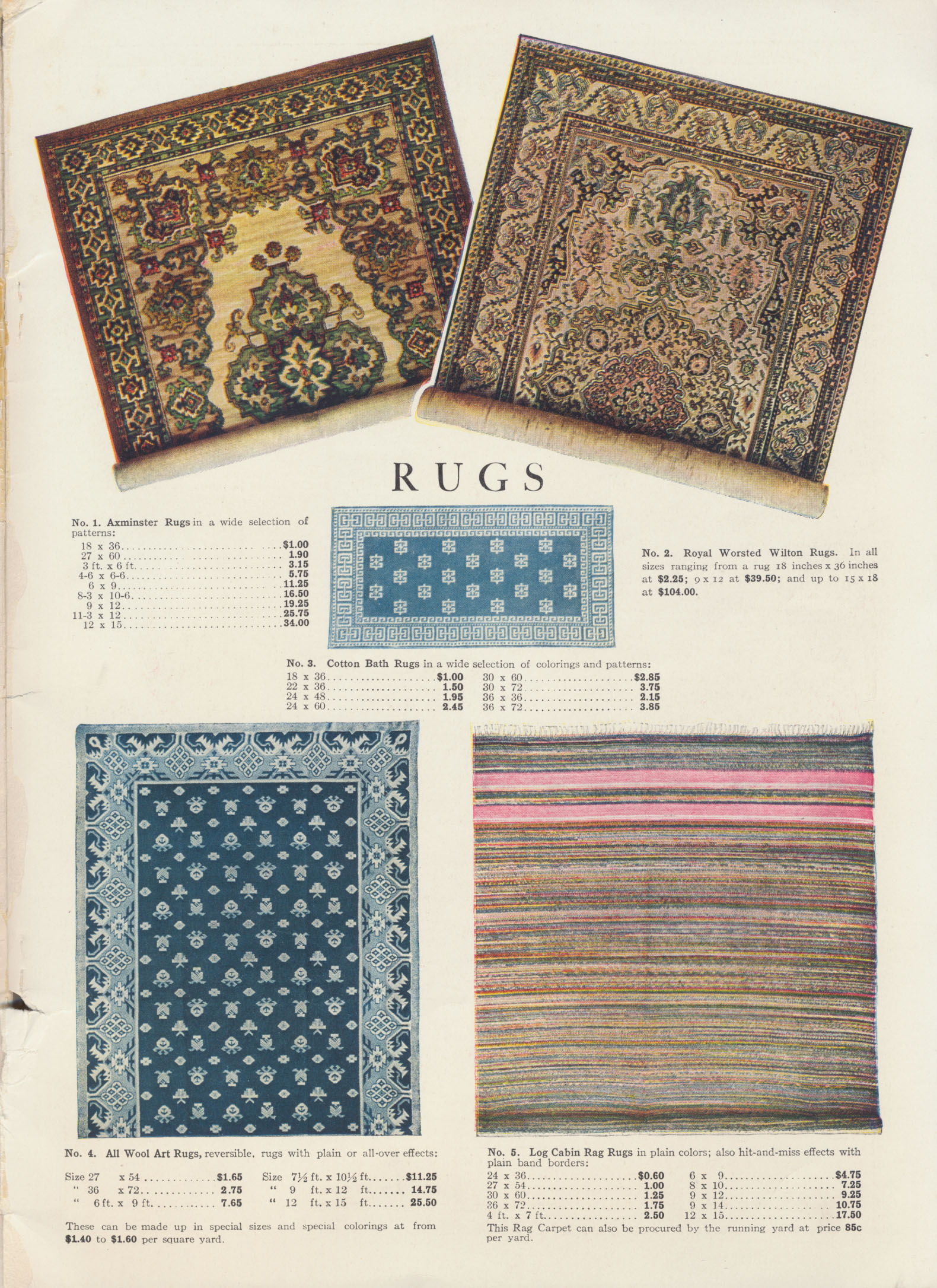

Just as curtains add a decorative touch to a room, so do rugs. The All Wool Art Rug (below, bottom left) was reversible and described as having “plain or all-over effects.” The particular one illustrated below includes shades of blue, but according to its description it was also available in “special colorings.”

Another option was the colorful Log Cabin Rag Rug shown below (bottom right). Besides plain colors, it was also available in “hit-and-miss effects with plain band borders.”

Cotton Bath Rugs were sold in a variety of colors and patterns. Though the catalog does not give specific details, one bath rug is shown below (middle) in shades of blue.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), inside back cover, Rugs.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), inside back cover, Rugs.

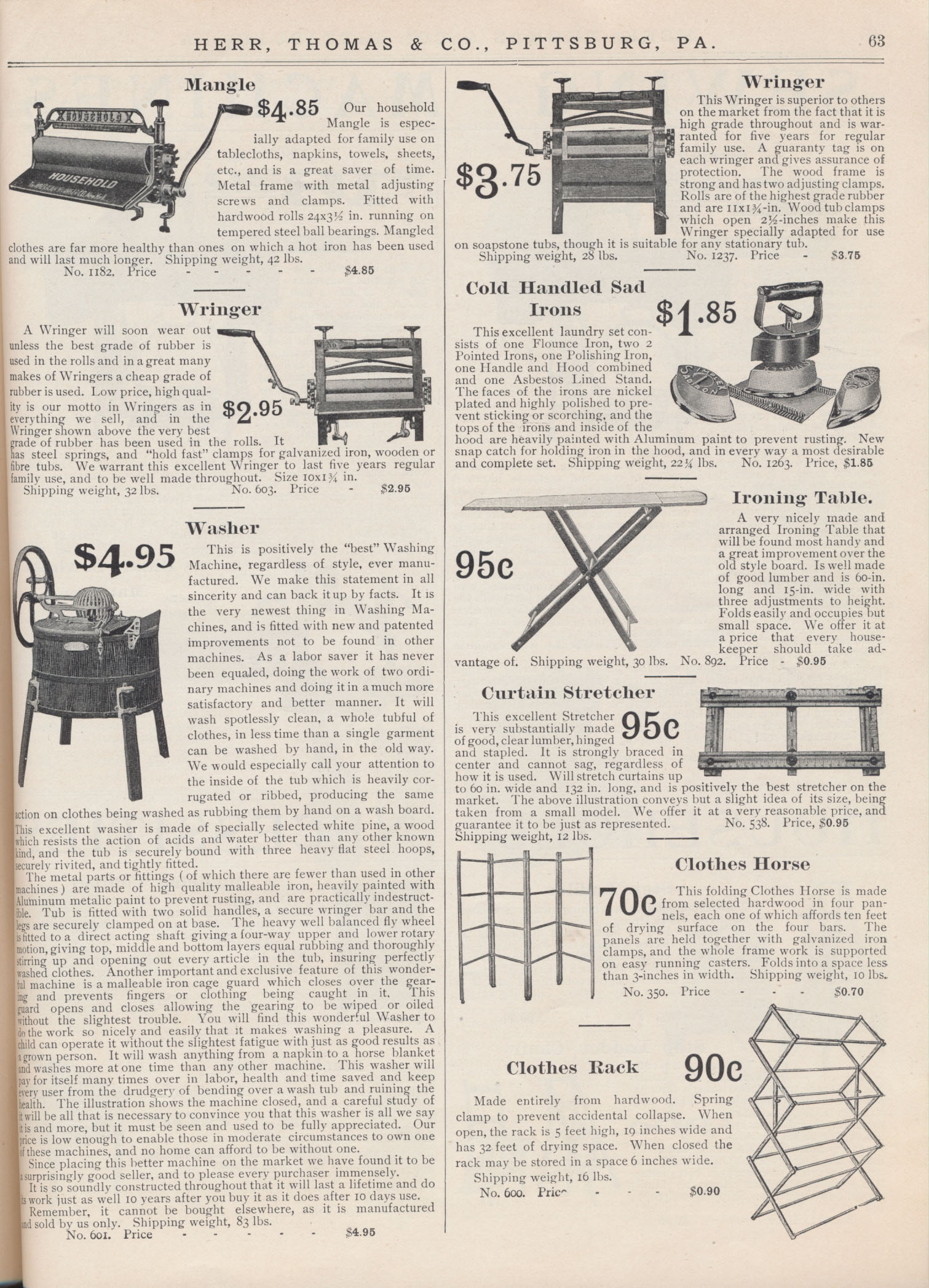

Now let’s travel a few years further back in time to 1907. This trade catalog is titled Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. The company sold a variety of household items via mail order. In previous blog posts, we highlighted writing supplies and related furniture as well as lawn and porch furniture and even groceries. Now let’s explore a few items in the “Laundry Furnishings” and “Household Necessities” sections.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.What did a clothes washer look like in the early 20th Century? Perhaps a family in 1907 bought the Washer pictured below (bottom left, shown in the closed position). The interior of its tub was heavily corrugated or ribbed which, according to the catalog, made the machine capable of “producing the same action on clothes being washed as rubbing them by hand on a wash board.” To prevent fingers or clothing from getting caught, a malleable iron cage guard covered the gearing, but it was possible to open the guard to clean the gears. The catalog also mentions that this machine was capable of washing something as small as a napkin or as large as a horse blanket.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.What did a clothes washer look like in the early 20th Century? Perhaps a family in 1907 bought the Washer pictured below (bottom left, shown in the closed position). The interior of its tub was heavily corrugated or ribbed which, according to the catalog, made the machine capable of “producing the same action on clothes being washed as rubbing them by hand on a wash board.” To prevent fingers or clothing from getting caught, a malleable iron cage guard covered the gearing, but it was possible to open the guard to clean the gears. The catalog also mentions that this machine was capable of washing something as small as a napkin or as large as a horse blanket.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 63, Mangle, Wringers, Washer, Cold Handled Sad Irons, Ironing Table, Curtain Stretcher, Clothes Horse, Clothes Rack.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 63, Mangle, Wringers, Washer, Cold Handled Sad Irons, Ironing Table, Curtain Stretcher, Clothes Horse, Clothes Rack.

How did you communicate with family and friends in 1907? Perhaps a Biaphone was installed in the home, as illustrated below (bottom right). The Biaphone provided a means of communication between two rooms or two nearby buildings by using the same wiring as the electric bell or annunciator. It required wire 500 feet in length with a Biaphone installed at each end of the line. Maybe it was helpful for quick conversations between family members in separate rooms of a house or even with the next-door neighbor.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 65, Bissell Carpet Sweeper, Baby Walker, Pants Pressers, Electric Bell Outfit, Webster’s New Standard Dictionary, Mail Box, 12 Piece Toilet Set, Cuspidor, Fire Proof Strong Box, Biaphone.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 65, Bissell Carpet Sweeper, Baby Walker, Pants Pressers, Electric Bell Outfit, Webster’s New Standard Dictionary, Mail Box, 12 Piece Toilet Set, Cuspidor, Fire Proof Strong Box, Biaphone.

Another form of communion is letter writing. For that, a mailbox, such as the one shown above (bottom left), might have been handy. This Mail Box, manufactured of cast iron, was capable of being securely locked. It featured a letter drop, or slot, to deposit thin envelopes along with the ability to fully open the top to deposit thicker envelopes and remove mail. It also featured a wire paper holder and “peep hole in the bottom covered by sliding shutter.”

Many other household necessities are illustrated in this section of the catalog such as a Pants Presser, for creasing pants without using an iron and heat, and the Fire Proof Strong Box, to securely lock and store important and valuable papers and belongings.

Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) by John Wanamaker and Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Identifying Article Metadata in “The Avicultural Magazine”

This blog post was written by Taylor Smith, the 2019 Kathryn Turner Diversity and Technology Intern in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Web Services Department. At the time of her internship, Taylor was an undergraduate Computer Science student at Bowie State University. Her work in the summer of 2019 consisted of developing and coding a method for identifying article metadata in The Avicultural Magazine, a leading journal for the keeping of non-domesticated birds in captivity.

As a biology major with an interest in computer science, I had a curiosity for wildlife and a newfound love for coding. I kept the two in mind when searching for internships, and luckily for me, I was led to the Kathryn Turner Diversity in Technology Internship for the summer of 2019. When I saw that the internship would focus on working with zoo articles relating to botany and wildlife, I knew this was perfect for me.

I had never held an internship before, let alone one that involves coding (which I had started learning that year). I had no idea what to expect when coming into this internship, but I learned a lot more than I could have imagined. Throughout this internship, I learned what metadata was and why it was so important. I learned why having digitized articles available online was so crucial. I also learned that making information accessible took a lot more work than anyone would think.

In my first week, I was introduced to the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), an online digital library designed to make biodiversity literature available to the public. In this library, I was specifically working with The Avicultural Magazine. This was a journal created by the Avicultural Society in 1894 with the purpose of spreading information, advice, and updates on non-domesticated birds. The volumes are digitized by Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and processed through optical character recognition (OCR) for the convenience of zookeepers and other zoo curators. The only problem with this is that it takes scrolling through endless pages of articles to find the specific item you’re looking for. My job was to create code that finds metadata for these articles to make them much more accessible and citable.

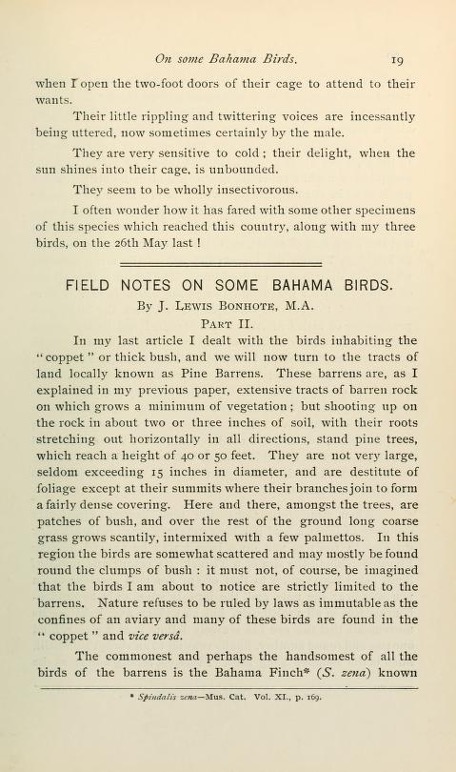

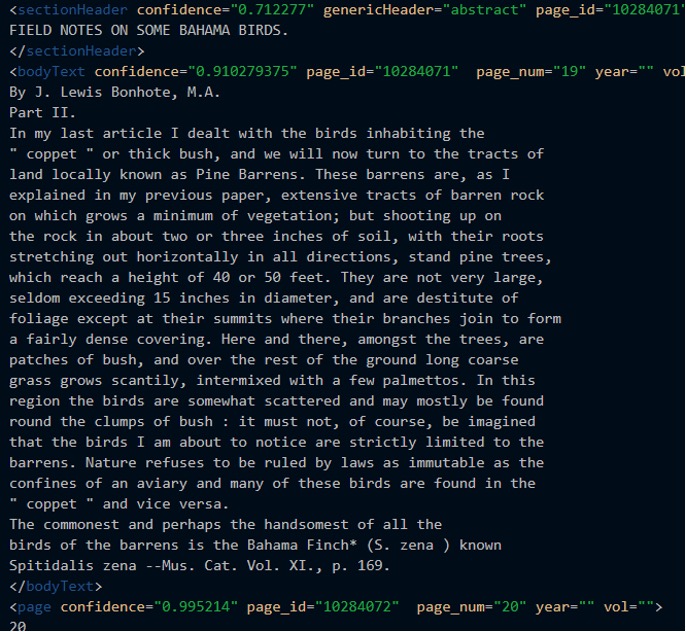

Below is an example of a page with the beginning of an article.

J. Lewis Bonhote, “Field Notes on Some Bahama Birds”, The Avicultural Magazine, volume 9, number 1 (November 1902): 19.

J. Lewis Bonhote, “Field Notes on Some Bahama Birds”, The Avicultural Magazine, volume 9, number 1 (November 1902): 19.

At first, I had to write code that would open up the directory of all the articles, open up one file at a time, and look for titles, page numbers, authors, etc. I set to work, but it was not long before we found that Penn State University and the National University of Singapore actually had a project named ParsCit that went through the files and searched for said data. The results are placed into an XML file, which was helpful to the process but not exactly as we needed.

My job then became loading and parsing the XML files using C++. The task was initially daunting: I had no idea what OCR was, what parsing meant, or what an XML file was. But with the help of Joel Richard, my supervisor and head of Web Services, it came a little more smoothly than I expected.

Joel really helped me take the next step in applying myself and taught me about regular expressions, parsing, XML files, and helped me with any trip-ups I had along the way. He also helped re-run the OCR for better material to work with, as well as pre-process the XML files so the data was more consistent and easier to work with.

After receiving the XML files I had to parse them. Parsing is essentially going through the tags of an XML file and picking out specific types of information. The process was not as simple as finding parts of the text marked as “author” or “title”, or even tags marked as such, but rather required me to take a look at the patterns occurring in the file. So, in my case, if I wanted the title, I would most often go to a <sectionHeader> tag since that’s where the Penn State code placed the titles it caught.

I checked the places I knew most of the titles were held (some were not caught at all and were in the middle of body text, which we couldn’t catch) and then looked for uppercase letters since all the titles were capitalized. Then, I checked if there was a “By” in either the <sectionHeader> tag or in the following <bodyText>tag. If nothing was found, then it wasn’t deemed an article. For authors, if there was an article found, then the “By” search would lead to an author every time. The next picture is an example of the OCR from one of the articles. You can see in this particular one the title is in the section header tag, but the author is in the body text tag.

Example of OCR for J. Lewis Bonhote, “Field Notes on Some Bahama Birds”, The Avicultural Magazine, volume 9, number 1 (November 1902): 19.

Example of OCR for J. Lewis Bonhote, “Field Notes on Some Bahama Birds”, The Avicultural Magazine, volume 9, number 1 (November 1902): 19.

For Page Numbers and Page IDs at BHL, I looked into the attribute of a tag. In the screenshot, you can see page_id and page_num which are attributes of <bodyText>. I pulled the information from those tags and stored them as is.

Since the OCR is imperfect, sometimes the “B” in “By” was interpreted as maybe an “E” or maybe the “V” in “Vol” was found as a “Y”. I did some very specific checking so that for as many cases as possible, as long as the very specific conditions were met, the information was found. We used regular expressions which looked for certain arrangements of these similar characters to determine the author, volume, date, and similar data.

After finding and storing the data, much of the remaining work was cleaning up what I had. That meant taking off any extra spaces, periods, capitalizing the first character of each word, and making the rest lowercase, or maybe refining the results even more. This was to make it easier for the humans who correct the results afterward. The code is effective, but not perfect. When the human cleanup was complete, the articles were imported into the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

While interning, I was able to go on many tours including the Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex collections, the Joseph F. Cullman Library 3rd Library of Natural History, and behind the scenes of the National Zoological Park. From viewing James Smithson’s books at the Cullman to watching the process of restoring aged and delicate books in the Book Conservation Lab to learning about mole rats, each tour showed a different but equally fascinating aspect of the libraries, as well as their involvement with the Zoo. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing the older objects, as it was very cool to see things that have held importance for such a long time and how times have changed.

The Zoo tour was led by branch librarian and supervisor Stephen Cox. Both Stephen and Jackie Chapman, Head of the Digital Library and Digitization, were extremely helpful, generous, and informative throughout the internship. They even helped me and intern Katerina Ozment create a poster to present at the Association of Zoos and Aquariums symposium! Katerina’s internship was focused on manually collecting and analyzing metadata from a related journal, the Animal Keepers’ Forum.

Kathryn Turner, the sponsor of my internship, is an inspiring woman I had the privilege to meet and share my story with her. It was motivating to see another woman with a very similar background to mine rise up in the STEM world and conquer it. I’m so grateful that I had the opportunity to intern and learn at the Smithsonian Libraries (now Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) that summer. I not only was able to expand my knowledge in my field but was also able to meet very intriguing people and see how things work behind the scenes.

Editor’s Note: Since the writing of this post, the National University of Singapore has developed and released a neural net version of their ParseCit software. This greatly improves the potential effectiveness of future computer-based automatic identification of articles building upon Taylor’s groundwork.

How Yellowstone Was Saved by a Teddy Roosevelt Dinner Party and a Fake Photo in a Gun Magazine

A chill rain drizzled over guests arriving at Bamie Roosevelt’s midtown brownstone near the corner of Madison Avenue and East 62nd Street in December 1887. There weren’t many of them, but all had two things in common: they were New York’s most influential and rich social elite, and they all loved hunting big game. All were hand-picked by the hostess’s brother, Theodore Roosevelt, to facilitate his newfound interest in the conservation of the American West. That small gathering became the first domino in a long line that ended in the protection of Yellowstone, the first environmental advocacy group in the US, and the creation of the American National Parks system.

Teddy was in the nadir of his career. His 3rd place finish in the New York City Mayoral race foretold doom in the realm of politics. His North Dakota ranch was devastated by winter storms (later known as The Big Die-Up) and on the verge of collapse. His latest book on his Western adventures, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, received a middling review in the popular sportsmen’s magazine, Forest and Stream, which praised his prose but harped on “the author’s limited experience” (Forest and Stream v.24, pg. 451). T.R. was evidently so incensed at the aspersions on his Western manliness that he showed up at the Forest and Stream editorial offices in New York to demand to speak to whoever wrote the article. That very visit led to Roosevelt’s midtown dinner party.

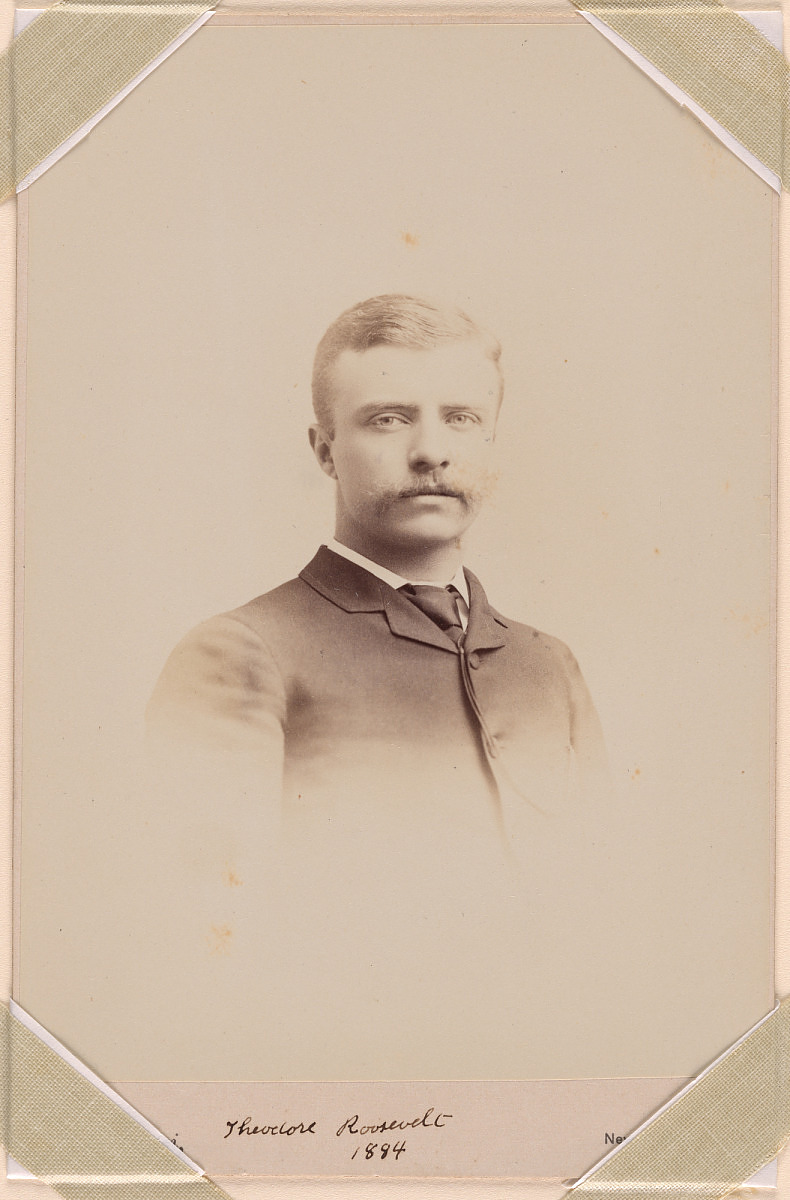

Photograph of Theodore Roosevelt by Julius Ludovici, 1884. Object number NPG.81.125. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Photograph of Theodore Roosevelt by Julius Ludovici, 1884. Object number NPG.81.125. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The evening may have gone something like this: first, he plied his guests with the rich bounty of his table and cellar with many toasts and courses. Roosevelt’s glass was unlikely to contain much alcohol (there was even a later court case about his abstention from drunkenness), but his hard-drinking younger brother Elliott and others may have partaken in the bon-vivant cocktails popular at the time. Then during the game course traditional to late 19th century gatherings, the conversation is adeptly steered by Teddy to their subject of common interest: hunting. Over yet another toast, Roosevelt proposes the formation of club named for America’s two most legendary hunters and committed to their shared values: fair chase, preservation of game, and “manly sport with the rifle.” Thus was formed the Boone and Crockett Club.

It could have ended there, with a private club whose members were required to have killed a large North American animal according to their own rules of engagement. But this group would grow in fame because of one of its founding members: George Bird Grinnell. At the time of this gathering, Grinnell stood out among the invited guests for his anonymity. He wasn’t a millionaire like Rutherford Stuyvesant or John Jay Pierrepont, or a famous man of the West like Albert Bierstadt or Bronson Rumsey, or an influential socialite like J. Coleman Drayton or Archibald Rogers. George Bird Grinnell was just a scientist, interested in joining expeditions to the West as a naturalist and studying the Native peoples of that region. He did have two qualities that drew Roosevelt to him, though: he loved Yellowstone and he edited a sportsmens’ magazine called Forest and Stream. Yes, Grinnell was the very person who published the backhanded review of Roosevelt’s book. Their confrontation led to a friendship that hatched the plan to gather the powerful crew of socialites and advocates for the West.

Photograph of George Bird Grinnell by William Notman. Object number NPG.77.184. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Grinnell went on many expeditions to the American West and fell in love with its natural beauty.

Photograph of George Bird Grinnell by William Notman. Object number NPG.77.184. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Grinnell went on many expeditions to the American West and fell in love with its natural beauty.

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives holds an extensive run of Forest and Stream, beginning with the first volume in 1873. While our physical copies are located in the Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex location, readers can find digitized versions of Volumes 1- 95 online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Part of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ work during the pandemic has been improving metadata in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, helping titles like Forest and Stream become more accessible to the world. Grinnell became editor-in-chief of the publication in 1881, using it as a tool to raise awareness of conservation issues, especially of his beloved Yellowstone, which he visited in 1875 as part of the Ludlow Expedition.

But in 1888, Yellowstone was in big trouble. Even though the area had achieved National Park status (the first in the US) in 1872, the designation was toothless. Poachers ran rampant, railroad companies eyed its majestic passages as thruways for their locomotives, and the Army had set up a fort to make war on the Native people of Yellowstone and deny them rightful access to their land. So Grinnell and the Boone and Crockett Club began a petition to Congress, published in the pages of Forest and Stream among its coverage of hunting trips, fishing tips, and shooting competitions. First a column of names, then page after page of supporters, many cajoled into participation by the Boone and Crockett Club’s socially influential measures, like Roosevelt and his chums, as evidenced by the frequent appearance of high-level New York socialites on these lists, many of whom included acquaintances of the likes of Stuyvesant and Drayton.

“Yellowstone Park Petition”, Forest and Stream, Volume 30 (April 30, 1888): 246.

“Yellowstone Park Petition”, Forest and Stream, Volume 30 (April 30, 1888): 246.

But all that effort didn’t move Congress to act, despite year after year of attempts. That all changed on May 5, 1894, when Forest and Stream published an account of the capture of an infamous poacher, Edgar Howell. He had previously eluded apprehension because the U.S. Cavalry, who was tasked with patrolling the park, had to catch a perpetrator in the act of poaching in order to pursue and arrest them. Unbelievably, the Army only had a single patrolman for the entirety of Yellowstone. This patrolman happened to be near Howell during a shooting and got the drop on the poacher and was able to call for help on the new-fangled telephone. The story was covered in full by the lone correspondent to as yet overwinter in Yellowstone: Emerson Howe. But it wasn’t Howe’s breathless reporting of the killing of dozens of buffalo that spurred national outrage; it was the images of Howell’s animal victims left lying in piles on the plain, titled by Grinnell as “The Butcher’s Work.”

“’Forest and Stream’s’ Yellowstone Park Game Exploration”, Forest and Stream, Volume 42 (May 5, 1894): 377.

“’Forest and Stream’s’ Yellowstone Park Game Exploration”, Forest and Stream, Volume 42 (May 5, 1894): 377.

Except they weren’t pictures of the bison that Howell had killed. These pictures were used in an Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution from seven years earlier. Grinnell was apparently sent the original photographs by William T. Hornaday, whose collection of living animals formed the basis of the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park. No record has yet been found illuminating how or why the decision to fake the photographs was made. Of important note, Grinnell’s trickery wasn’t necessary to convict Howell, who confessed and never amended his ways.

After L. A. Huffman, “A Dead Bull” and “Buffalo Skinners at Work.” From William T. Hornaday, “The Extermination of the American Bison, with a Sketch of Its Discovery and Life History,” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1887, part 2 (1889): pl. IX.

After L. A. Huffman, “A Dead Bull” and “Buffalo Skinners at Work.” From William T. Hornaday, “The Extermination of the American Bison, with a Sketch of Its Discovery and Life History,” Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1887, part 2 (1889): pl. IX.

The ruse was effective though: only days later Congress passed the Act to Protect the Birds and Animals in Yellowstone National Park, and to Punish Crimes in Said Park. Known as the Lacey Act of 1894, the law finally outlined a punishment for poaching on public lands. The first person convicted under the Act was none other than Edgar Howell.

Roosevelt went on to strengthen the protections of public lands, campaigning on conservation for the Vice Presidency in 1900 and later as President, establishing the National Parks system that currently protects not just Yellowstone, but 85 million total acres of American lands. T.R. continued to have a close relationship with Forest and Stream, contributing articles heralding conservation reforms and hosting organizational meetings at his home in Oyster Bay.

Further Reading:

Alan C. Braddock, “Poaching Pictures: Yellowstone, Buffalo, and the Art of Wildlife Conservation,” American Art, 23:3 (2009): 36-59.Supporting Access to Zoological Literature: Article Definition in the Biodiversity Heritage Library

This post was written by Katerina Ozment, part of the Smithsonian Libraries’ 50th Anniversary 2019 Intern Class, funded by the Secretary of the Smithsonian and the Smithsonian National Board. At that time she was an undergraduate at the University of Oklahoma, majoring in History and Biology. Katerina is now a graduate student at the University of Tennessee, College of Communication and Information, School of Information Sciences. The internship program is now the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ 50th Anniversary program.

For zookeepers to most effectively care for their animals, they need access to zoological research, as well as a way to communicate with other zookeepers. One way for zookeepers to do this is through participation in professional organizations such as the American Association of Zoo Keepers (AAZK) and its publication, Animal Keepers’ Forum (AKF). AKF contains current research, husbandry techniques, animal enrichment activities, conservation news, and other topics.

Due to AKF’s role in facilitating this kind of communication, Smithsonian Libraries (now Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) requested permission from AAZK to digitize the Libraries’ copies of AKF and make them available through the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). BHL is an open access digital library for biodiversity works. Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is one of the only BHL member libraries that supports an active zoo and therefore has a unique commitment to providing for this user community in BHL.

Although the publication was already available online, searching for specific articles remained difficult. This is because AKF was uploaded as whole issues as opposed to individual articles. It was uploaded this way because the metadata (data about the work) associated with the Libraries’ record applies to each issue, not each article. Descriptive metadata includes information such as the title, volume, issue number, or date of a work. This metadata ensures that BHL is searchable and that specific works can be located.

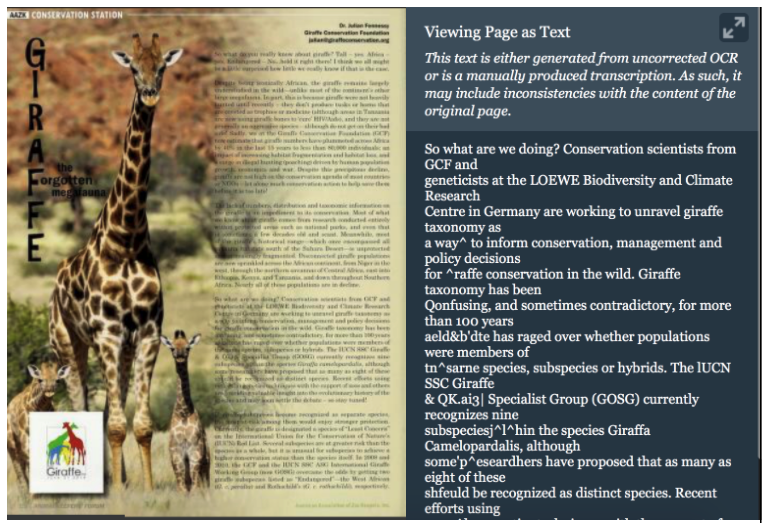

However, researchers are used to having article-level metadata and often search for a specific article or article topics. Currently, if a researcher searched for a specific article author in the name field, it would not bring up the articles written by that author for AKF. Similarly, if an article’s title was searched for in the title field, it would not be found. Without article-level metadata, such as article titles or article authors, these resources are much harder to find. It is possible to do a full text search and find articles by title or author that way; however, the OCR (optical character recognition) the full text search relies on is not corrected. If there are mistakes in the OCR, the search terms won’t be found. This is especially true when an article has graphic design elements, or text overlaid on a picture, as both contribute to poor OCR.

Despite this, it is sometimes possible to search for an article’s title or author(s) using the full text of the issue, which is made available via OCR (Optical Character Recognition). However, the OCR that the full text search relies on frequently contains mistakes and cannot be manually corrected at this scale. If there are mistakes in the OCR, the search terms won’t be found. This is especially true when an article has graphic design elements, or text overlaid on a picture, as both contribute to poor OCR.

This article, “Giraffe: Forgotten Megafauna”, left, has both an acrostic title and is overlaid on a photo. As a result, the OCR, right, did not pick up the title, and the OCR text of the article has a number of errors.

This article, “Giraffe: Forgotten Megafauna”, left, has both an acrostic title and is overlaid on a photo. As a result, the OCR, right, did not pick up the title, and the OCR text of the article has a number of errors.

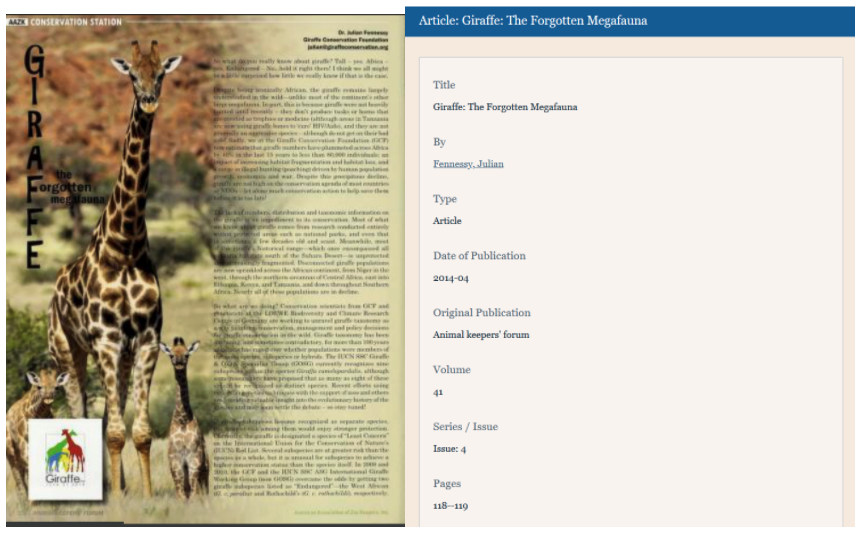

To address this, I worked to add article-level metadata and access to issues of AFK. This is possible due to the recently added batch upload tool for BHL. The batch upload tool allows the metadata for an entire set of articles to be added to BHL at once, following a template.

Because AKF is more of a newsletter or magazine than a formal journal, determining what counted as an article was not always obvious. For each AKF issue, I needed to determine what should be defined as an article (for the purposes of this project) and then add the relevant metadata (including author, title, page numbers, etc) to the template. Letters from the editor, interviews, and news summaries were some parts of AKF that caused the most questions. I often consulted with my supervisors, Jacqueline Chapman (Head, Digital Library & Digitization) and Stephen Cox (Branch Librarian for the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute), to determine what should be defined as an article and what shouldn’t. In the end, focusing on what was most important to animal care research was a key aspect of this definition. The articles I added to BHL included research done by zookeepers, interviews with conservationists, and columns summarizing zoo-related news. However, there are still many parts of AKF that I did not articlize, but could be added later. These include the letter from the editor, “About the Cover,” or AAZK chapter news.

The same article, “Giraffe: Forgotten Megafauna”, left, now with article metadata manually applied, right. The title is now searchable within BHL and for other services that use BHL’s data, despite the complicated layout and underlying uncorrected OCR.

The same article, “Giraffe: Forgotten Megafauna”, left, now with article metadata manually applied, right. The title is now searchable within BHL and for other services that use BHL’s data, despite the complicated layout and underlying uncorrected OCR.

Aside from defining articles, another challenge was ensuring consistency for author names across issues. If an author uses a nickname in one article and their full name in another, or if their name has changed over time, only one version of the name should be recorded as the author. This is necessary so that each individual only receives one BHL “creator ID” and so that searching their name will bring up all their work, regardless of the name variation used. This required that the preferred version of the name be used on all articles.

For this part of the process, I needed to learn about Name Authority work, an aspect of library science focused on solving this problem. Name Authorities establish IDs for individual authors, such as those provided by the Library of Congress, VIAF, and ORCID. VIAF (Virtual International Authority File) is a compilation of name authority records from libraries across the world, including the Library of Congress. An ORCID is an ID that the individual author creates for themselves. Its use is increasingly common among researchers across many fields and helps ensure that an author’s works are all connected even if the author changes their name. In each case, the name associated with the BHL “creator ID” should be the one used in one of these Name Authorities.

I was able to find and associate these IDs with their authors in AKF using a tool called OpenRefine. Earlier, in July 2019, I attended a Data Carpentries workshop at the Smithsonian. In addition to receiving an introduction to several data management and manipulation tools, including Python and SQL, I also learned how to use OpenRefine. I was able to use this tool to more easily determine if there was an author ID associated with any of the AKF authors. OpenRefine allows the user to upload a list of authors and use the reconcile tool to find possible matches in either ORCID or VIAF. From there, I could determine if the ID was the author from AKF, or someone else with the same name. While these IDs were very useful for determining preferred names, there were occasional mistakes. In one instance, the VIAF record for the author included works by two different people with the same name. I submitted a correction to VIAF, with the help of Lesley Parilla (former Cataloging and Bibliographic Librarian).

I was able to complete AKF issues from 2010-2016 during my internship. I also worked to document the process I used and decisions my team made, ensuring a future intern or staff member will be able to take up the project from where I left off.

AKF is very varied in how the articles are formatted, how the authors’ names are listed, and how accurate the OCR is; therefore, a manual process worked best for this project. It is also possible to create article-level metadata by writing a script to collect the necessary information, if the title is consistent in layout. I worked with Taylor Smith (Summer 2019 Kathryn Turner Diversity and Technology Internship) and her supervisor, Joel Richard (Head, Web Services & IT), who created metadata for the journal Avicultural Magazine in this way. We were able to share the results of both of our projects as a poster, Supporting Access to Zoological Literature: Article Definition in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, at the Association of Zoos & Aquarium’s (AZA) conference in September 2019.

Cover, Animal Keeper’s Forum, V. 43: No. 12 (2016).

Cover, Animal Keeper’s Forum, V. 43: No. 12 (2016).

Whereas my work on AKF in BHL was focused on providing article-level access to one title, my other project allowed me to take a broader view of zoological literature. I was able to help Stephen with his work on a bibliography for the AZA’s Orangutan Species Survival Plan (SSP). An SSP is a holistic approach developed by conservationists to help support captive breeding programs for endangered species. Stephen functions as a curator of relevant peer-reviewed literature for several SSPs, maintaining comprehensive bibliographies. This specific SSP bibliography serves as a resource for zookeepers caring for orangutans and contains citations for articles and books about a variety of husbandry topics. I located each listed source online and added it to Zotero, a reference management tool, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of each citation. This tool will be shared amongst primate keepers around the world.

As I worked on my two projects, both focused on how the Libraries and Archives supports zookeepers, I was able to appreciate the many ways in which librarians and zookeepers work together. I have spent a lot of time in zoos and libraries; however, I was unaware of how connected the two are.

Over the course of the summer of 2019, I learned so much about how libraries work, the different careers within a library, and how libraries provide resources for their users. I was constantly amazed to see the careful thought and work that goes into tools that I had always taken for granted as a library user. Aside from my projects, I’ve been able to talk to so many people who work here and each one has given me more insight into what it means to work in a library and the variety of types of librarians. I know that everything I’ve learned will be invaluable as I pursue my career in the library and information sciences.

A Late 19th Century Camping Experience

Do you remember summer camp as a child? Perhaps you went on a camping trip with your family or maybe you camped out in your own backyard. The Trade Literature Collection located at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives holds a variety of catalogs. Some illustrate camping equipment. Have you ever wondered what it was like to camp over a century ago? This trade catalog might give us an idea.

The trade catalog is titled Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882) by Murray & Baker. Just as the title suggests, it includes tents, and as we will learn later, one style even had an awning. It also illustrates camping stoves and camp furniture as well as hammocks for that late afternoon nap.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), front cover.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), front cover.

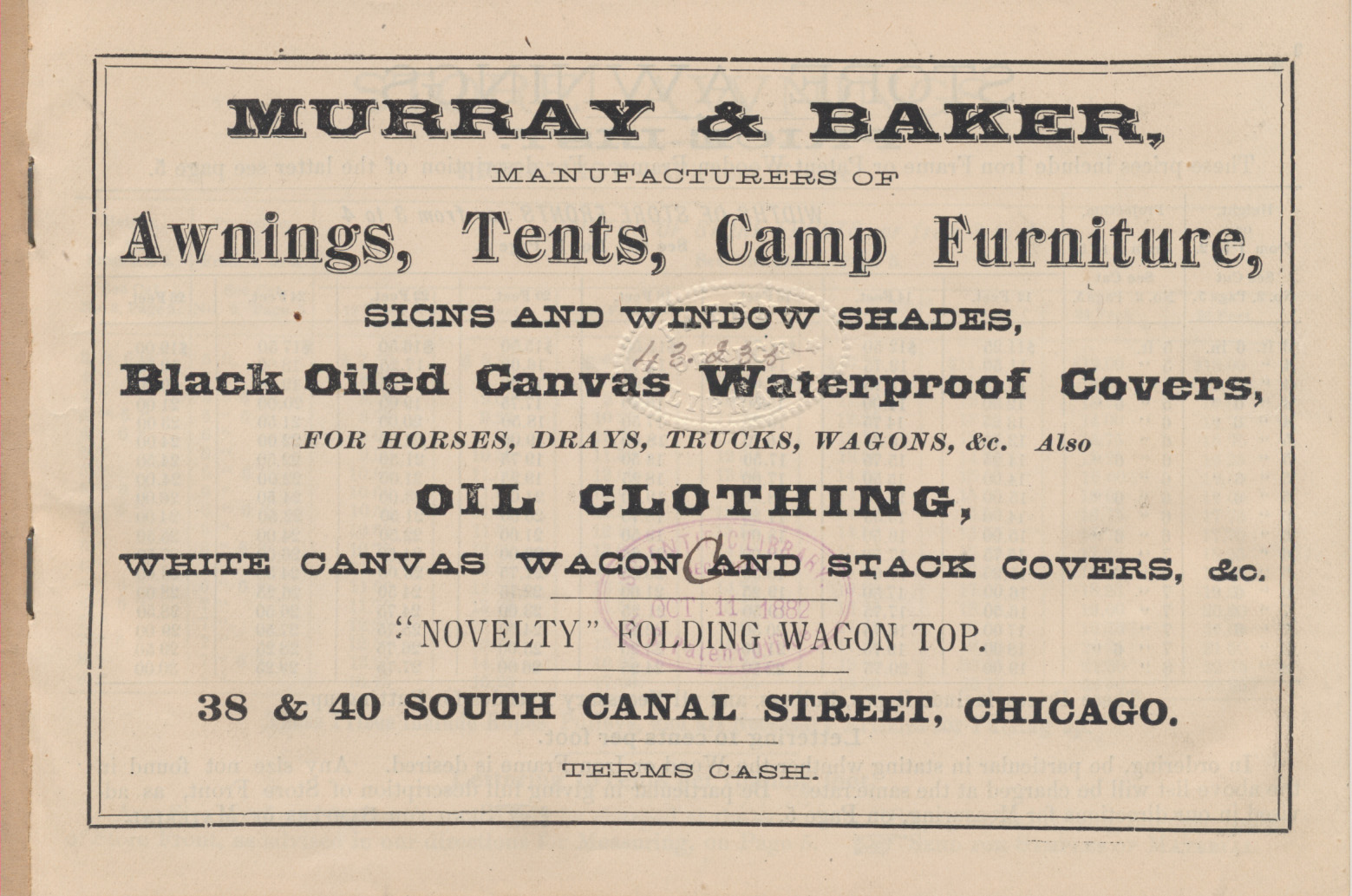

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), title page.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), title page.

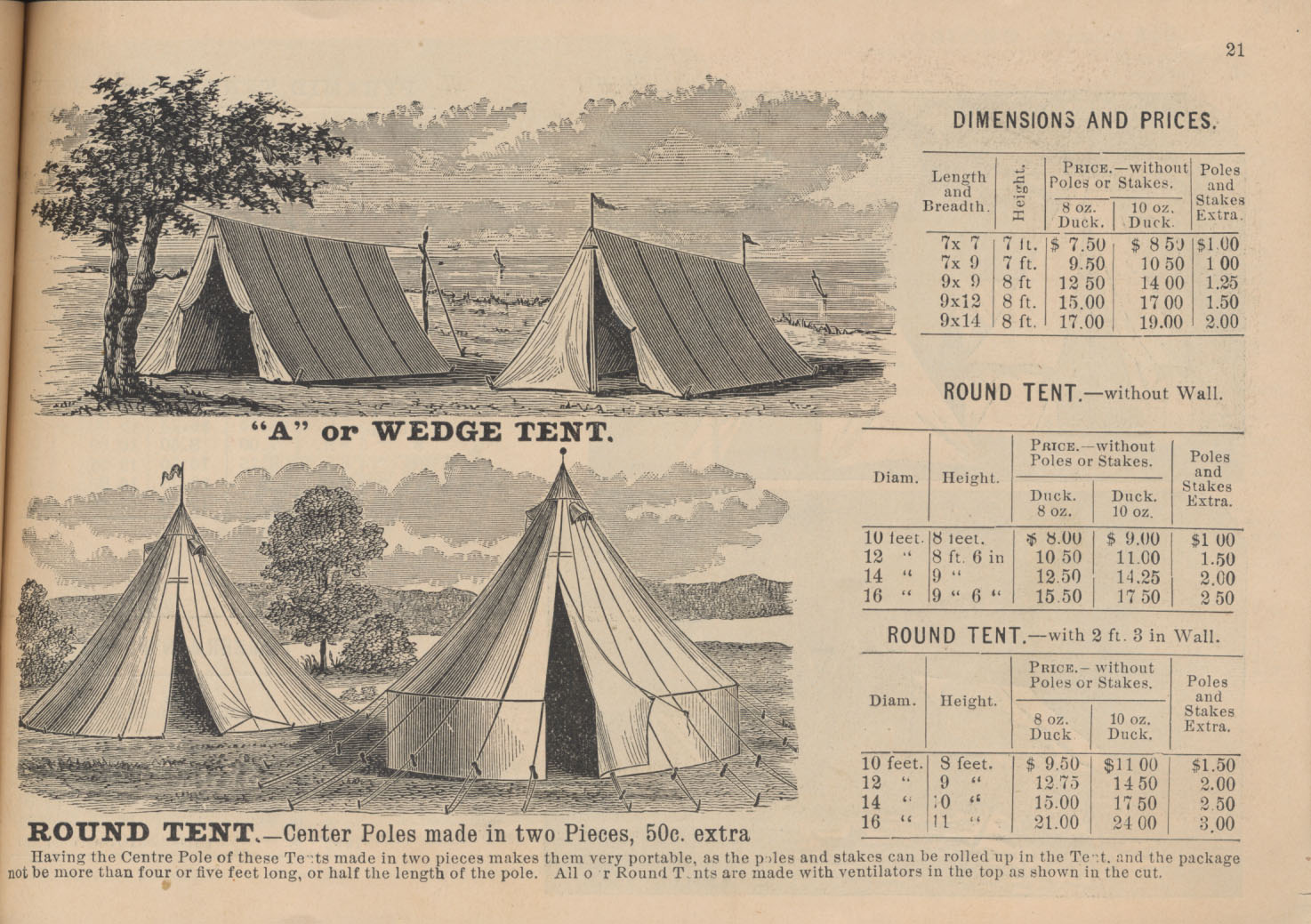

The Round Tent, illustrated below, varied between 8 to 11 feet in height and 10 to 16 feet in diameter. It was available in two designs. One design included a wall measuring two feet three inches in height before sloping inward to create a point at the very top. The other design did not include the wall. As shown below, ventilators were located near the point of these tents. This was likely a convenient and welcome feature as it provided air circulation. The Round Tent with a wall is pictured below, bottom right, while the Round Tent without a wall is pictured to its left.

The portable nature of this tent made it easy to pack for a camping trip. The center pole of the tent conveniently folded into two pieces and then all the poles and stakes were rolled inside the folded tent.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 21, “A” or Wedge Tent, Round Tent without a wall, and Round Tent with a wall.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 21, “A” or Wedge Tent, Round Tent without a wall, and Round Tent with a wall.

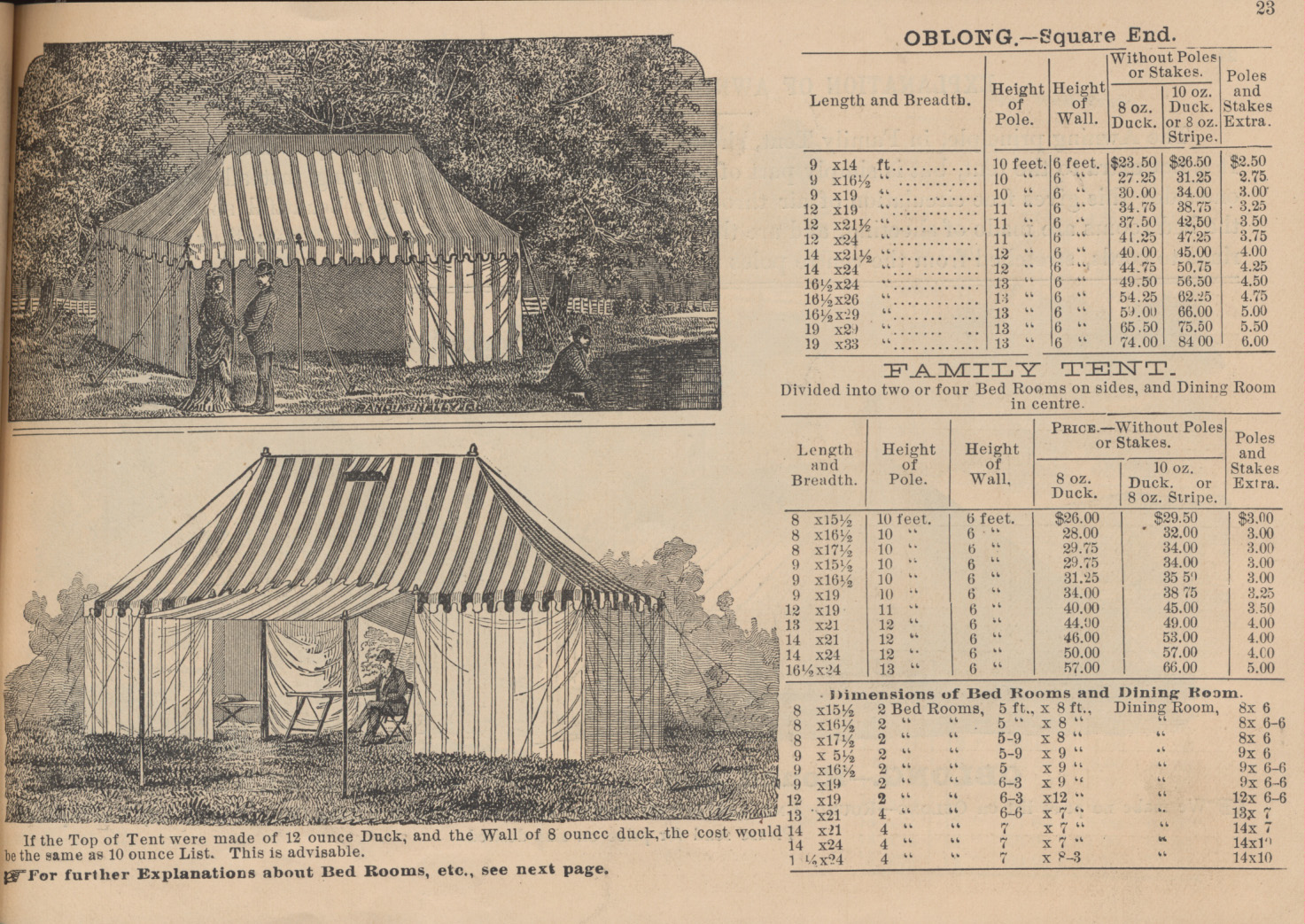

Those who wanted their own space might have preferred the Family Tent, illustrated below (bottom left). The common room was described as a Dining Room and located in the center of the tent. Two or four bedrooms surrounded the dining room. The bedrooms were separated by sheeting, six feet in height, attached by rings onto cords that stretched from the center poles to the sides of the tent. This tent also had a wall measuring 6 feet in height before sloping inward to create a peak at the top.

The Family Tent provided a handy built-in feature for the comfort of its occupants. It had an awning that was created by simply lifting one wall of the tent and supporting it with poles. As illustrated below, the addition of the awning created both air circulation and shade.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 23, Oblong Tent with Square End and Family Tent.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 23, Oblong Tent with Square End and Family Tent.

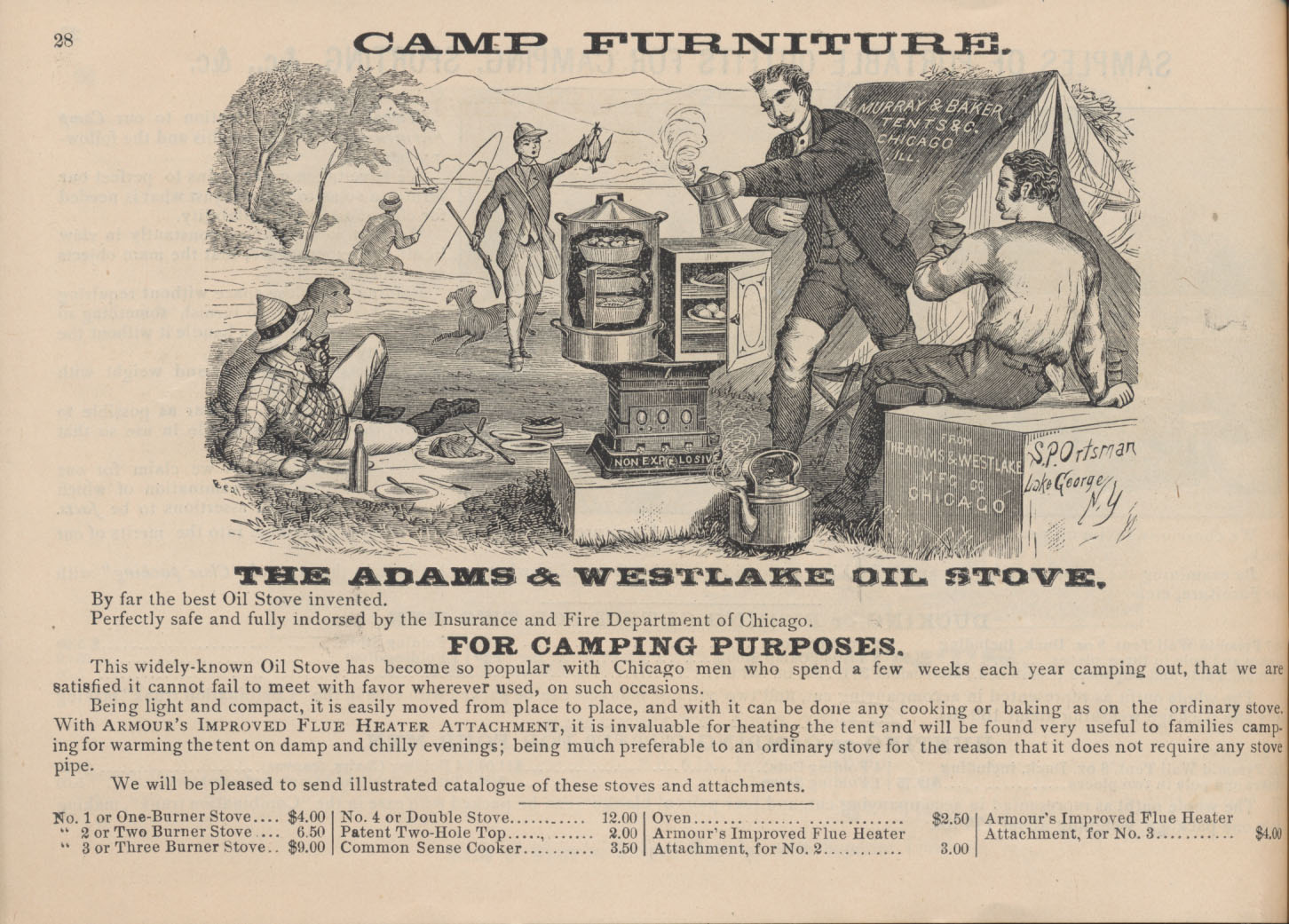

In a previous blog post, we highlighted camp furniture such as folding tables, chairs, beds, and the combination trunk/cupboard/table. Now let’s take a look at camp stoves. The “Adams & Westlake Oil Stove” is pictured below and included several options. It was available with one, two, or three burners, as a double stove, or even an oven for baking. Besides cooking, it also provided warmth on chilly nights by using “Armour’s Improved Flue Heater Attachment.”

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 28, “Adams and Westlake Oil Stove.”

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 28, “Adams and Westlake Oil Stove.”

Though the “Adams & Westlake Oil Stove” was described as “light and compact” and “easily moved from place to place,” another camp stove might have appealed to some campers due to its ability to be used as a packing crate. The camp stove, pictured below (top), doubled both as a stove and a packing crate. This stove was constructed without a bottom and relied on the ground to form its bottom. With no actual bottom, the stove was easily converted into a packing crate by simply turning it upside down. Then the stove pipe and cooking utensils were safely stored inside.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 29, Camp Stoves and Folding Stove.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 29, Camp Stoves and Folding Stove.

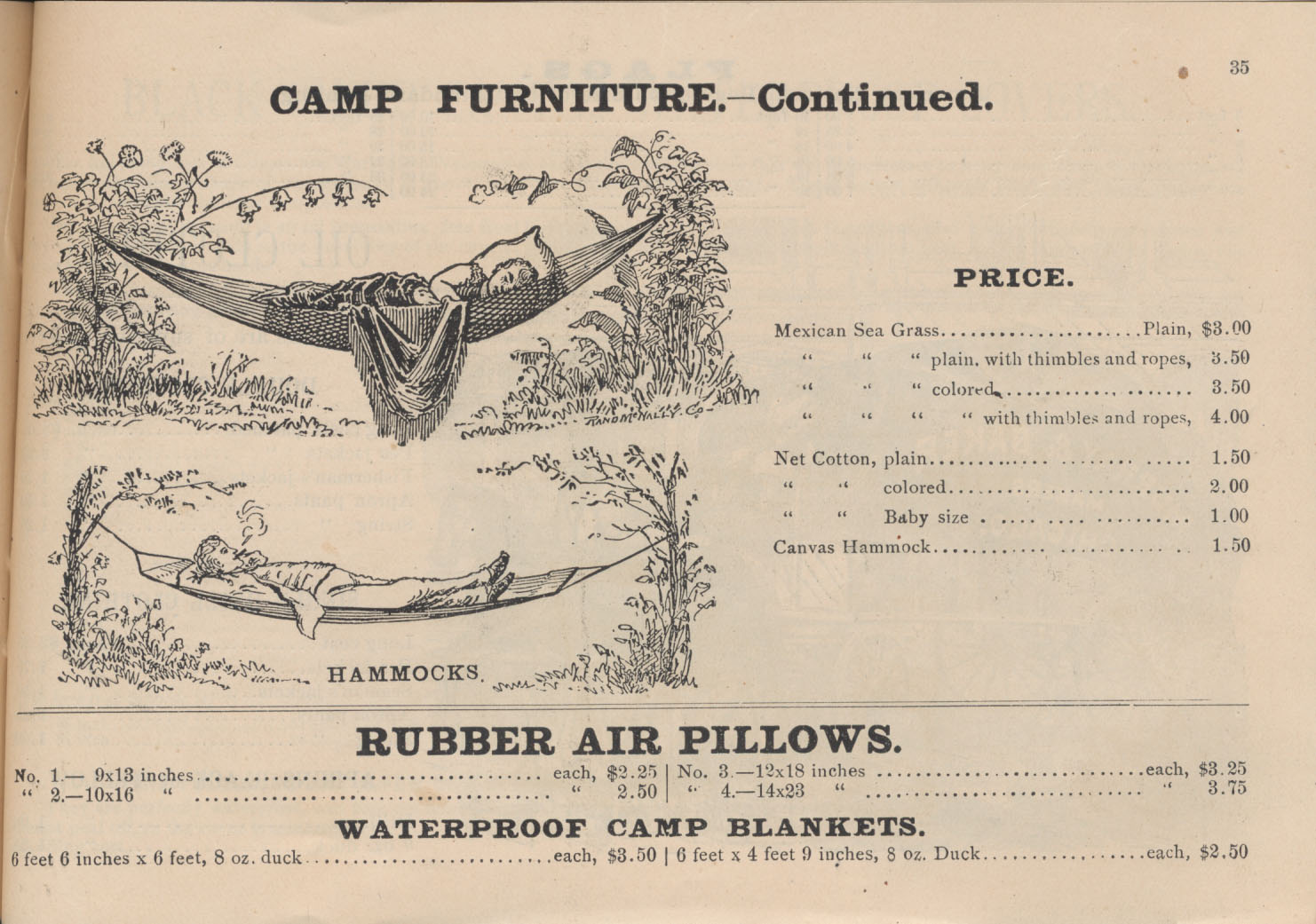

When it came time for an afternoon nap, these hammocks, shown below, might have looked inviting. Imagine a peaceful afternoon spent resting or reading a book outdoors in the fresh air. The Rubber Air Pillows and Waterproof Camp Blankets mentioned on the same page might have been useful as well.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 35, Hammocks, Rubber Air Pillows, and Waterproof Camp Blankets.

Murray & Baker, Chicago, IL. Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882), page 35, Hammocks, Rubber Air Pillows, and Waterproof Camp Blankets.

Awnings and Tents, Signs and Banners (1882) by Murray & Baker is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Murray & Baker sold more than just camping equipment. Among other items, they also provided awnings, buggy tops, wagon umbrellas, and waterproof wagon and horse covers as described in a previous blog post.

Falling for Field Books

Being an avid reader, every once in a while an item comes across my desk for digitization with such an intriguing story that I can’t help but get sucked into it. That’s what happened when I first saw one of James Eike’s field books. Now I know what you are thinking, “how does one get sucked into a field book?” Often times, field books are filled with lists of specimens or observations from the field, and those created by James Eike, an avid bird watcher and citizen scientist, are no exception. However, among the almost daily counts of birds observed by Eike are glimpses into his personal life, where, according to him, just about every day was glorious.

List of items Claire and Susan Eike received for Christmas in 1958. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 5, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Neg. No. SIA2012-0088.

List of items Claire and Susan Eike received for Christmas in 1958. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 5, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Neg. No. SIA2012-0088.

James Eike was born in Woodbridge, Virginia on September 29, 1911 to Carl and Sarah Eike. Shortly after starting at Georgetown University in 1928, he began recording his observations about the wildlife he saw around northern Virginia, especially birds and snakes. Unlike the lists of bird counts found in his later field books, Eike’s first few journals are more narrative in form. By 1930, he was keeping lists of the numbers and types of birds seen, as well as the date and location where he saw them. Eike graduated from Georgetown in 1932 and started working for the U.S. Public Health Service in 1934.

James Eike’s field book entry for April 6, 1971; his 31st Anniversary. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 8, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

James Eike’s field book entry for April 6, 1971; his 31st Anniversary. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 8, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

On April 6, 1940, James Eike married the love of his life, Claire. Their daughter, Susan, was born almost six years later on January 31, 1946. At that point, spotting and counting birds seemed to become somewhat of a family affair for the Eikes. Occasionally, James Eike would take his young daughter with him when he went to the nearby woods to count the birds, and on the weekends, sometimes the whole family would go together. Additionally, one page of Eike’s field book from “3-20-57 to 7-20-57” includes a list of birds that Claire saw while on a trip to Michigan in July while her husband stayed in Virginia. Claire and Susan also became members of the Virginia Society of Ornithology (VSO), a group which James Eike had actively participated in since 1933.

Sept. 8, 1951 – Sat: To woods with Susan 10:30-12:30. Wonderful weather… Sept. 9, 1951 – Sun: Another wonderful day – brisk in morning. To woods with Claire and Susan, 11:00-12:30. Saw and/or heard Swifts, Hummingbird…

In addition to the lists of birds, Eike’s entries and field books started to include notes about his personal life. Starting in 1957, in the back of just about every field book that spanned Christmas, he would record the list of gifts he, Claire, and Susan received that year. He also included little notes about their birthdays and his anniversary at the top of his entries for those days. Eike would even make notations about trips the family was taking, and after Susan left for college, his entries about her return home and departure back to school usually include a happy and sad face, respectively.

4-6-67 Thurs: 3 real gold ones [goldfinches] greeted me first thing – on my 27th anniv. with you, dear.

On February 8, 1983, James Eike died of cancer. Starting on January 21, 1983, Susan and Claire took over recording the daily bird counts for James, and even after his death, Claire continued to record the counts in the field book that James had started. She even noted their 43rd wedding anniversary on April 6, 1983. In her last entry in the book, Claire writes “My dearly beloved – I’ll keep trying to get a good list. I am feeding our birds well. I miss you.”

Note from James Eike to his wife, Claire, and daughter, Susan, dated February 9, 1961. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 5, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Note from James Eike to his wife, Claire, and daughter, Susan, dated February 9, 1961. Record Unit 7342 – James W. Eike Papers, 1927, 1950-1983, Box 1, Folder 5, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In 1984, the VSO created the James Eike Service Award in honor of the time and dedication James put into the society. The first recipient of the award was Claire Eike, in honor of her late husband. Eike’s love of both birds and family make his field books a joy to explore. The personal stories and reflections add to the layers of valuable information captured in his notes, making me fall in love with field books and the insight they can bring about both science and life.

Upcoming Event: Ask a Conservator – Emergency Management

Ask a Conservator: Emergency Management

Wednesday, June 23 at 5 pm ET

Cultural heritage is not renewable. If books, documents, pieces of art, or any other ephemera are destroyed in a fire, for example, they are likely lost forever. Librarians and archivists have a long history of responding to and preparing for the kinds of emergencies and disasters, both natural and human-inflicted, that threaten these important resources for economic development and tourism, as well as knowledge, creativity, and a sense of historically connected identity.

In our next “Ask a Conservator” program on June 23, Nora Lockshin, senior conservator, and Katie Wagner, senior book conservator, will share how they plan for and respond to potential emergency situations that could pose risks to the safety of our precious collections at the Smithsonian and those of our fellow cultural institutions around the country. They’ll also discuss how they are called on to assist with protecting and recovering cultural heritage around the world. And as always, there will be plenty of time for your questions!

Register now to attend this webinar via Zoom. Spaces are limited!

You can also watch this event on Facebook. To access the event, please be sure you are following Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. We recommend having our page open when it starts.

If you’re not able to watch live, don’t worry! This program will be recorded and made available for later viewing on our YouTube channel.

We’re seeking sponsors for this program. Donations will go directly to support preservation at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. If you’re interested in learning more about this opportunity, please contact our Advancement team.

A Digitization Journey, a Knowledge Journey: Personal and Professional Insights From My Work on Polynesian Researches

Na au iki a me na au nui o ka ʻike: The little and the large currents of knowledge.