Libraries' Blog

National Library Week Virtual Meeting Backgrounds from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

Screenshot of Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology background in use.

Screenshot of Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology background in use.

A year in to the COVID-19 pandemic and we’re guessing some of you might be missing your libraries. We know we are! To give your next video meeting some book-ish ambience and to celebrate National Library Week, we’ve put together a set of backgrounds that bring you into our spaces and, in some cases, right into the pages of our books.

Below are nine images just waiting to adorn your virtual walls. Some are recent photos of our library locations. Some are vintage views from the collections of Smithsonian Institution Archives. And a few are just favorite book illustrations with a collector’s vibe. Click on the image and save to your computer, then follow the instructions provided by your virtual meeting platform (Zoom, Microsoft Teams, etc.) to upload and use.

Library stacks in the National Museum of Natural History Library, main location.

National Museum of Natural History Library, main location. Click to enlarge and download.

National Museum of Natural History Library, main location. Click to enlarge and download.

Vintage juvenile aviation adventures shelved in the National Air and Space Museum Library‘s rare book room.

National Air and Space Library. Click to enlarge and download.

National Air and Space Library. Click to enlarge and download.

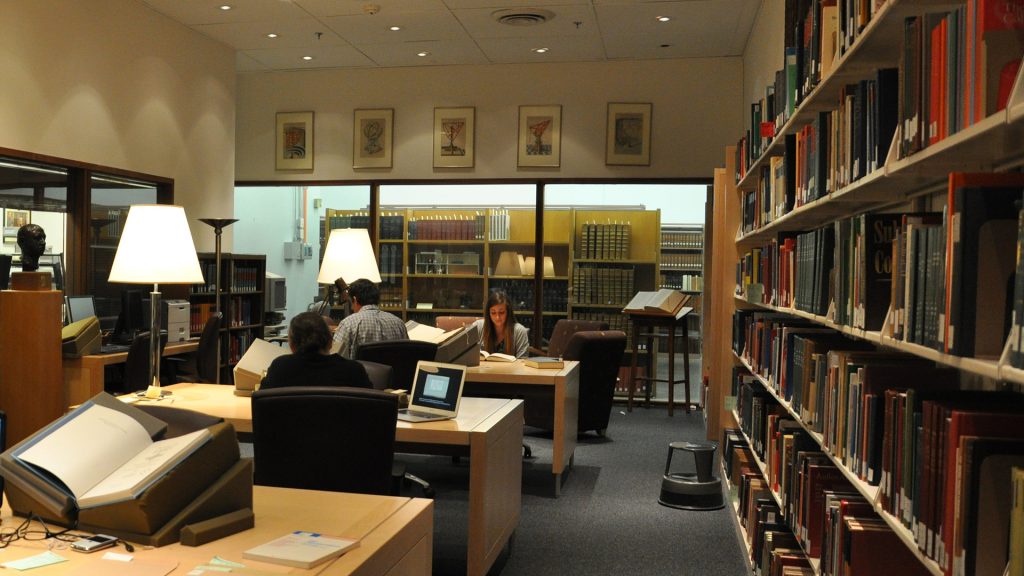

Reading room of the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. Photo by Liz O’Brien.

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. Click to enlarge and download.

Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. Click to enlarge and download.

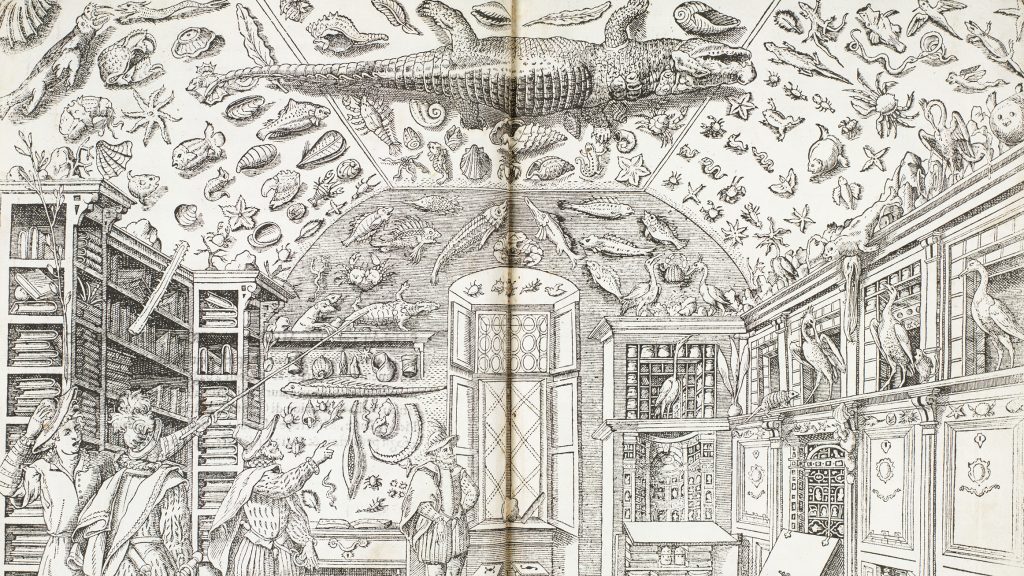

Double-page plate, Dell’historia natvrale di Ferrante Imperato napolitano libri XXVIII (1599), detail.

Double-page plate, Dell’historia natvrale di Ferrante Imperato napolitano libri XXVIII (1599), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Double-page plate, Dell’historia natvrale di Ferrante Imperato napolitano libri XXVIII (1599), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Plate No. 215, Le garde-meuble, v. 1 (1839), detail.

Plate No. 215, Le garde-meuble, v. 1 (1839), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Plate No. 215, Le garde-meuble, v. 1 (1839), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

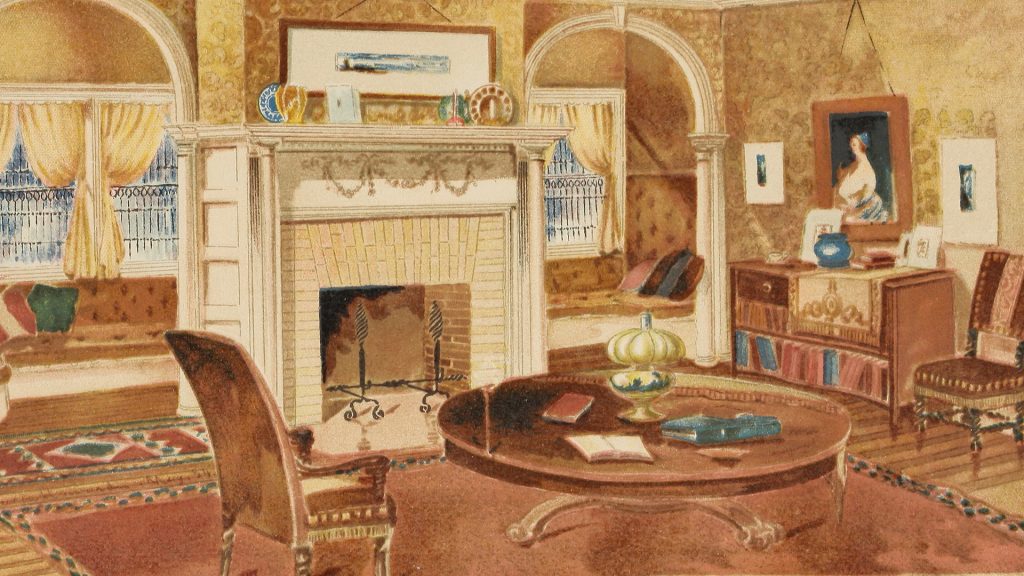

“Living Room”, The woman’s book v. I (1894), detail.

“Living Room”, The woman’s book v. I (1894), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

“Living Room”, The woman’s book v. I (1894), detail. Click to enlarge and download.

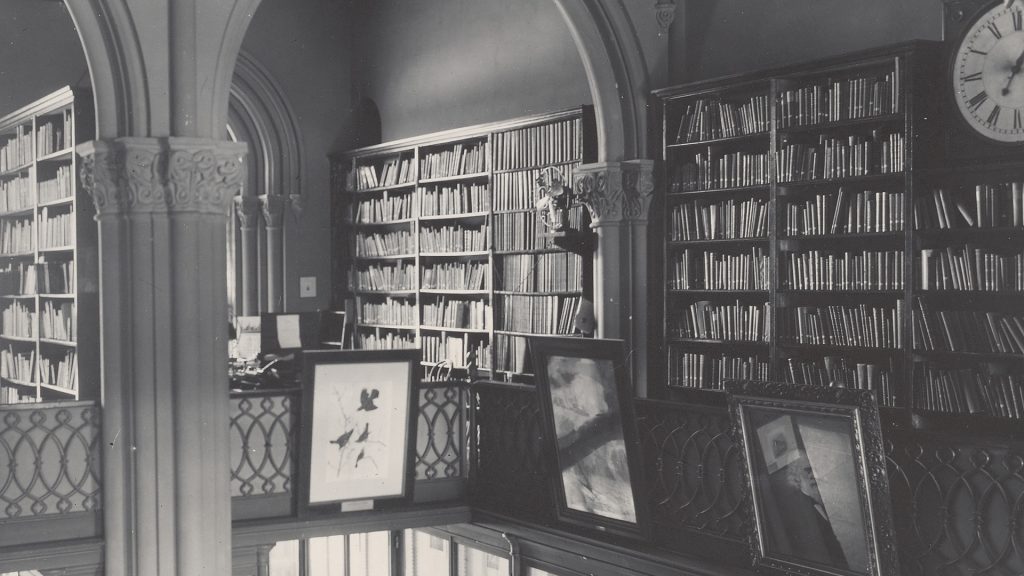

Library Stacks, Lower Main Hall, Smithsonian Institution Building, or Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B31_F38_002, detail.

Library Stacks, Lower Main Hall, Smithsonian Institution Building, or Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B31_F38_002, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Library Stacks, Lower Main Hall, Smithsonian Institution Building, or Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B31_F38_002, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

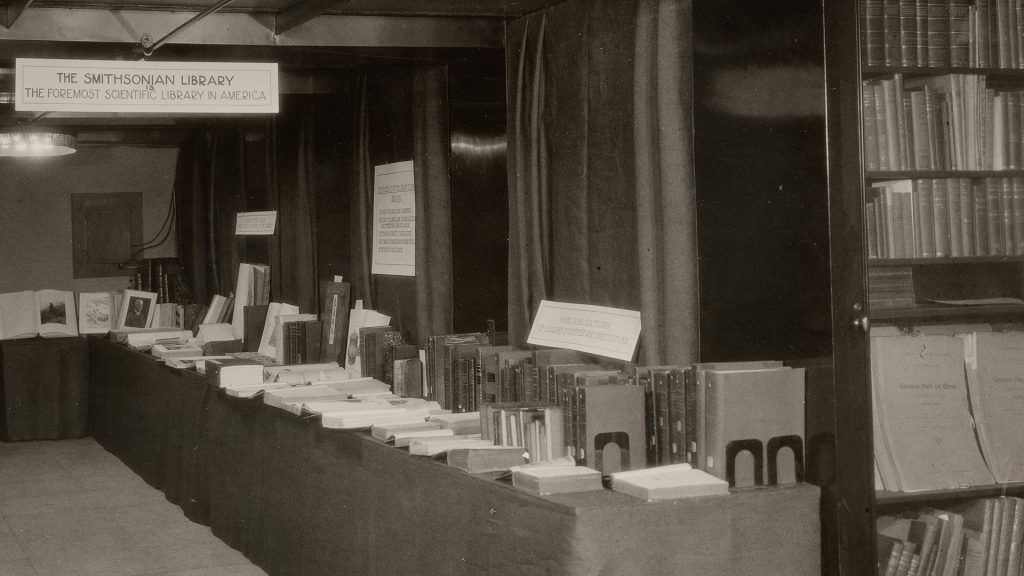

Conference on the Future of the Smithsonian, Smithsonian Library Exhibit, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B41_F09_035, detail.

Conference on the Future of the Smithsonian, Smithsonian Library Exhibit, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B41_F09_035, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Conference on the Future of the Smithsonian, Smithsonian Library Exhibit, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA_000095_B41_F09_035, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

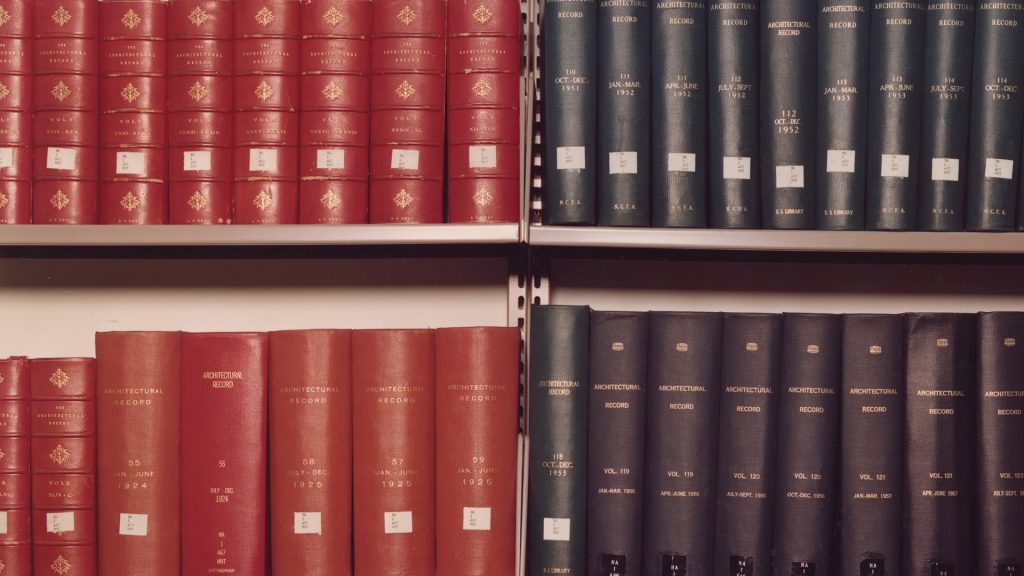

Museum of History and Technology Library, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 285, Image no. SIA2010-2160, detail.

Museum of History and Technology Library, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 285, Image no. SIA2010-2160, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Museum of History and Technology Library, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 285, Image no. SIA2010-2160, detail. Click to enlarge and download.

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles – National Library Week Edition

To celebrate National Library Week and the start of spring, we’ve put together another round of digital jigsaw puzzles! We hope these cheerful florals brighten your screens and bring you a few moments of peace, minus the pollen.

Play them right here on our blog or use the links to play full screen. Each puzzle is set at about 100 pieces but they are customizable to any skill set. Click the grid icon in the center to adjust the number of pieces. All of the images are available in our Digital Library, Image Gallery, Biodiversity Heritage Library or Smithsonian Institution Archives Collections. Feel free to explore and make your own!

Miss our previous puzzles? Find them here.

Rear Cover, The Conard and Jones Co. New Floral Guide (1898).

In 1897, Alfred Conard, already an established seedsman, and Antoine Wintzer joined with S. Morris Jones to become Conard & Jones Co. The company focused primarily on the growing and distribution of roses and flowering plants. This brilliantly lithographed rear cover of the firm’s Autumn 1898 catalog highlights “winter flowering bulbs”, many of which are also popular outdoor blooms in spring.

Play online: https://jigex.com/6z14

Rear Cover, The Conard and Jones Co. New Floral Guide (1898).

Rear Cover, The Conard and Jones Co. New Floral Guide (1898).

Jigsaw Puzzle

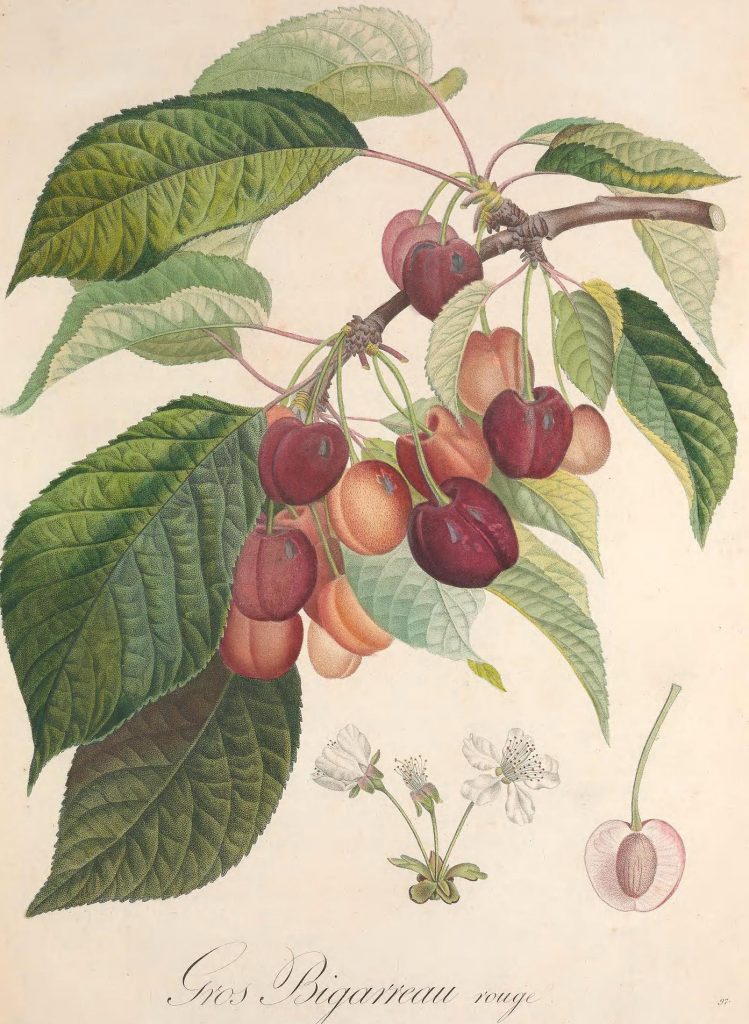

Cerisier Pl 7, Pomologie française : recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France, Volume 2 (1846).

Pomologie française : recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France , published in four volumes in 1846, is a delight for the senses. French botanist Pierre-Antoine Poiteau wrote the text, a study of French fruit plants and their cultivation. The lush illustrations were the work of Poiteau as well as fellow botanist and artist Pierre Jean François Turpin.

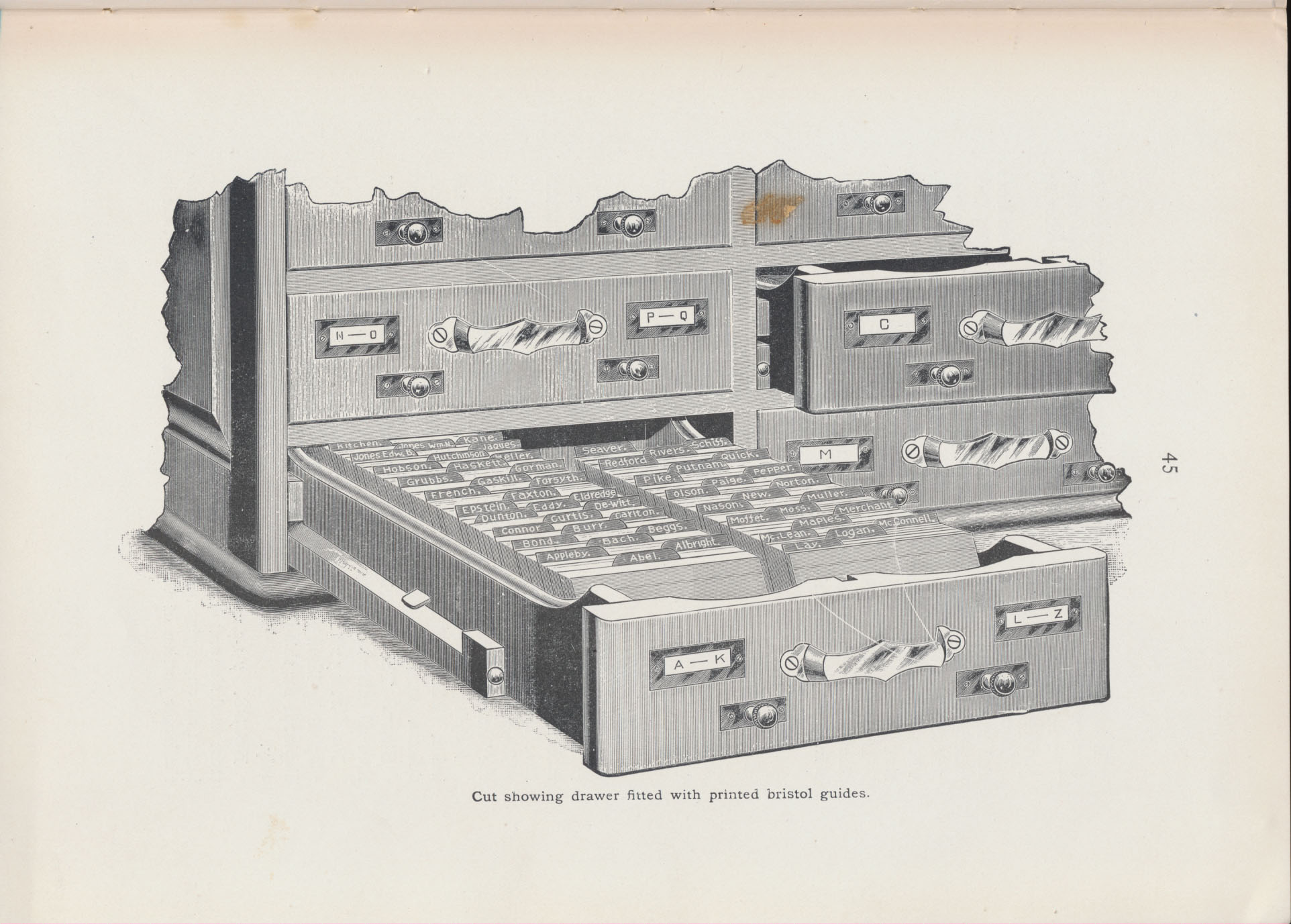

Play online: https://jigex.com/5SbS

Cerisier Pl 7, Pomologie française : recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France, Volume 2 (1846).

Cerisier Pl 7, Pomologie française : recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France, Volume 2 (1846).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Postcard of the Smithsonian Institution Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA2013-07202.

This early 20th century postcard offers a glimpse of the Smithsonian Institution Building, or “Castle”, designed by architect James Renwick, Jr. and completed in 1855. In the foreground is a statue of the first Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry, who served as the Institutions’ founding leader from 1846 to 1878. Modern visitors to the National Mall will note that Henry’s statue has since been moved closer to the north entrance of the building.

Play online: https://jigex.com/TRRi

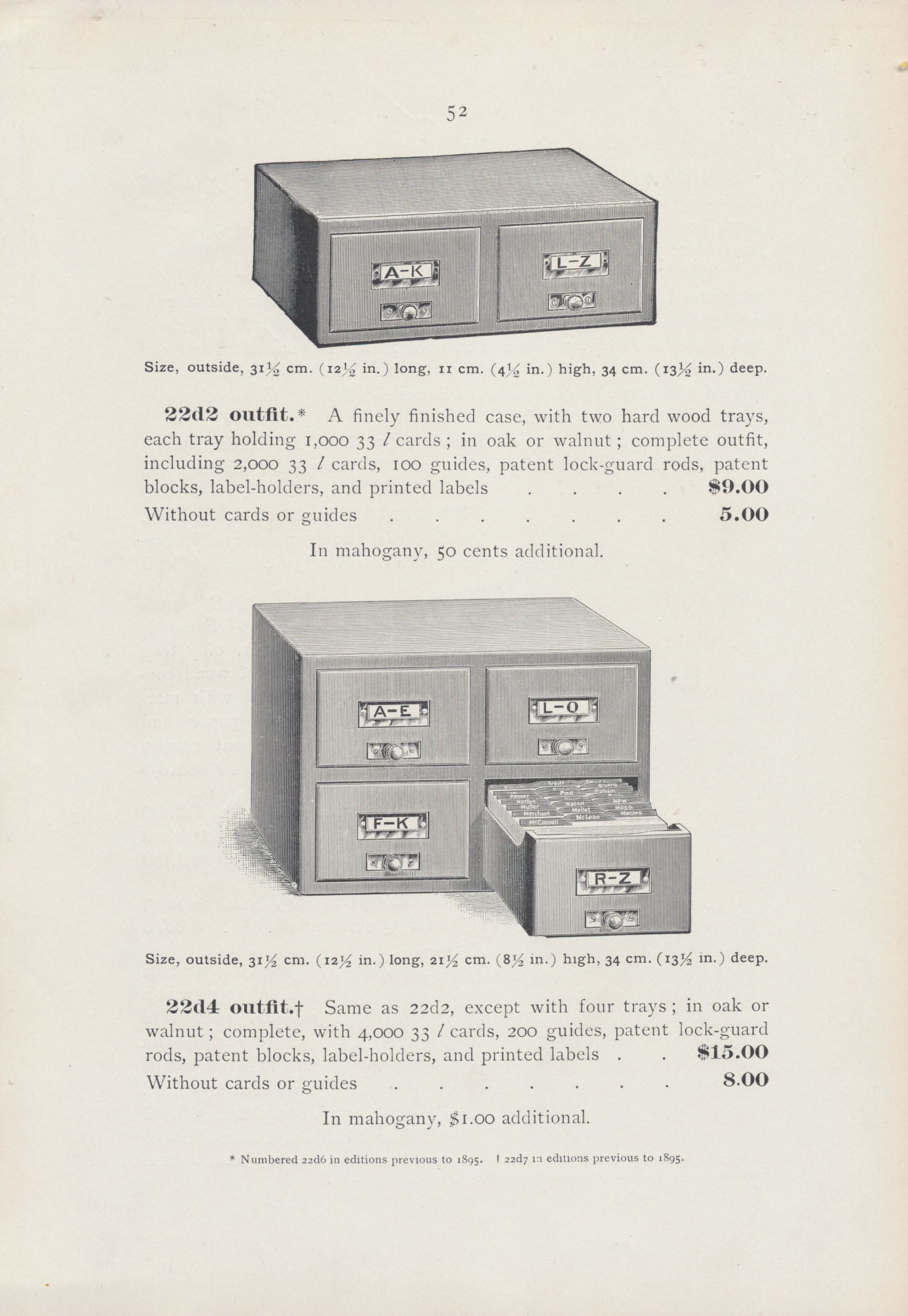

Postcard of the Smithsonian Institution Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA2013-07202.

Postcard of the Smithsonian Institution Castle, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Image no. SIA2013-07202.

Jigsaw Puzzle

Women gathering spring herbs, Haru no Fuji [1803].

This book by Katsushika Hokusai was a special New Year’s publication of kyōka poetry (mad verses) collection commissioned by a private kyōka salon. This is one of two color woodblock-printed illustrations that accompany the text, showing three women in delicately colored kimono gathering spring herbs. The seventh day of the Japanese New Year is called nanakusa no sekku or the festival of seven herbs, and traditionally included eating a rice soup or porridge with seven healthy herbs. Learn more about our Japanese illustrated books from the Edo and Meiji periods.

Play online: https://jigex.com/M82d

Women gathering spring herbs, Haru no Fuji [1803].Jigsaw Puzzle

Women gathering spring herbs, Haru no Fuji [1803].Jigsaw Puzzle

Plate VIII, Gazette du bon ton, t. 2 (1913)

Long-time blog readers and social media followers might have noticed that we are big fans of the illustrations in Gazette du Bon Ton. This French art and style journal was published by Lucien Vogel between 1913 and 1925. This plate from August 1913 highlights an afternoon dress by design house Worth. Learn more about Gazette du Bon Ton.

Play online: https://jigex.com/6o8u

Plate VIII, Gazette du bon ton, t. 2 (1913).

Plate VIII, Gazette du bon ton, t. 2 (1913).

Jigsaw Puzzle

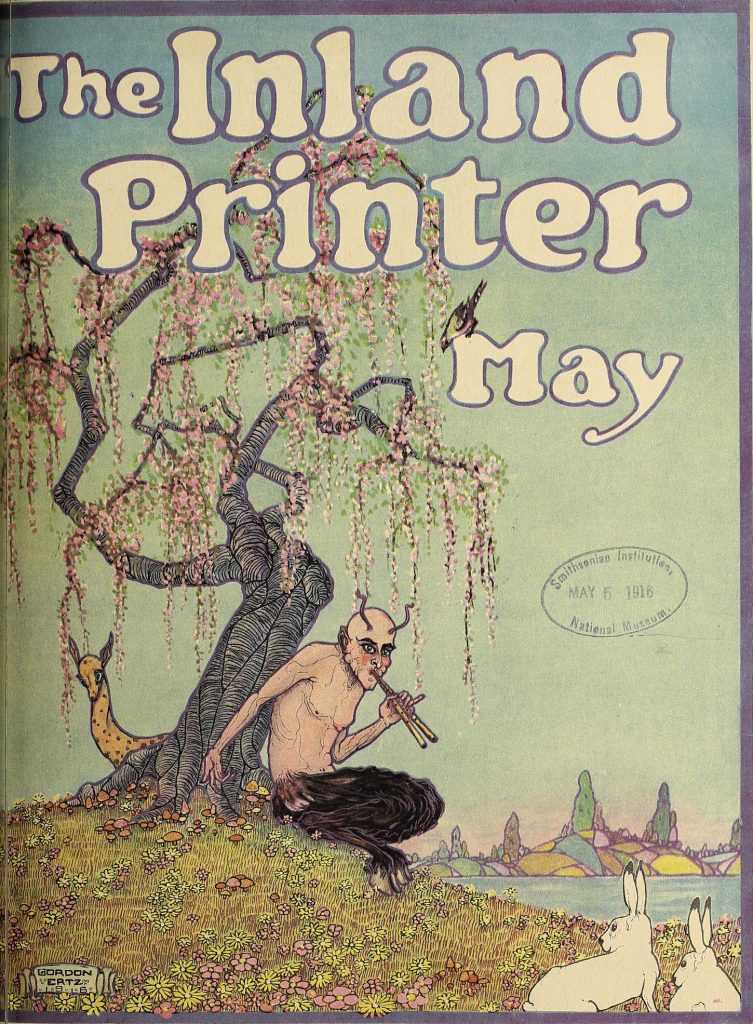

Cover, The Inland Printer, Volume 57 (May 1916).

This fantastical cover image from the May 1916 issue of The Inland Printer is courtesy of illustrator Gordon Ertz. The periodical, a trade journal for the printing industry, is said to be the first to feature different cover art with each issue. The interiors of the issues were just as interesting, as the publication highlighted new advances in graphics, printing and paper making.

Play online: https://jigex.com/rcFQ

Cover, The Inland Printer, Volume 57 (May 1916).

Cover, The Inland Printer, Volume 57 (May 1916).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Plate IV, Papillons (ca. 1925).

Emile-Allain Séguy was a popular French designer throughout the Art Deco and Art Nouveau movements of the 1920s. He designed primarily patterns and textiles and was heavily influenced by the natural world. Papillons is a book of designs based on wing patterns in butterflies commissioned by American textile manufacturer F. Schumacher and Co. Learn more about Séguy on the Biodiversity Heritage Library blog.

Play online: https://jigex.com/1oq6

Plate IV, Papillons (ca. 1925).

Plate IV, Papillons (ca. 1925).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Celebrating National Library Workers Day

This week (April 4-10, 2021) is National Library Week and Tuesday is set aside to celebrate National Library Workers Day. It’s a wonderful opportunity to highlight the important contributions made by all library staff. In honor of National Library Workers Day, we caught up with a few staff members to hear what they’ve been working on over the past year. Although they’ve been largely offsite during the ongoing pandemic, our staff remain dedicated to providing information to researchers at the Smithsonian and around the world. Learn more about how they’re sharing their expertise, caring for collections, and connecting data in a totally virtual environment.

Sharad J. Shah

Collections Management Librarian

“With over twenty branches in the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives system, numerous challenges involving collections and collections space are bound to arise. Even while the museums and research centers are closed to the public, Smithsonian staff continue to work behind the scenes to ensure the Smithsonian’s treasured collections are safe and secure. Currently, I am working with other units overseeing the management of collections across the Smithsonian’s museums and research and storage facilities. These projects range from transferring library material between branches, to upgrading library storage units, to planning a future home of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives materials (see: Suitland Collections Center Executive Summary). Our goal is to iron out plans, for both diving into and successfully completing, collections and collections space-related projects once we return to normal operations.”

A rendering of the proposed Master Plan in 40 years, prepared by Bjarke Ingels Group

A rendering of the proposed Master Plan in 40 years, prepared by Bjarke Ingels Group

Nilda Lopez,

Library Technician, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Library

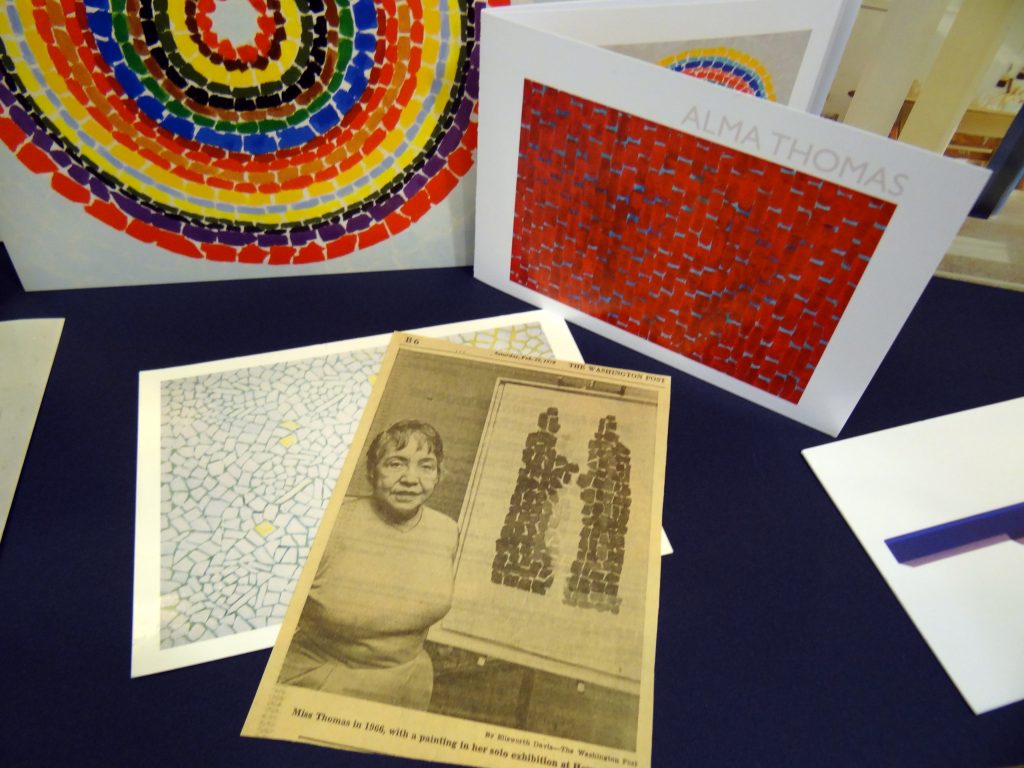

“Several locations in the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives house special collections called the Art and Artist Files. They are a valuable resource for art historical research on emerging regional and local artists. They hold information on artists, art collectives, and galleries and contain ephemera from flyers, clippings, press releases, brochures, invitations and so much more. As we continue to grow the Art and Artist Files, our intent is to make the information they contain more digitally accessible to the public, and one of these ways is our effort to make our collections discoverable in Wikidata. You might be familiar with Wikipedia, and Wikidata is related—it is a free and open database software that allows anyone to contribute with structural data. Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has several pilot projects with Wikidata, and the Art and Artist project is quickly reconciling data into the larger structure of Wikimedia. This process involves using Open Refine, a tool that “cleans” data, to link Wikidata to details from our files such as artists’ names and life dates. And most importantly, with more than 60,000 names in our files, it involves lots of time! It is our hope that this project will increase the diffusion of knowledge, linking our data in as many places as possible. Other “GLAM” institutions—galleries, libraries, archives and museums–are collaborating on this project and we hope to grow and create a web of data for the future.”

Selection of Art and Artist File material from the file of Alma Thomas.

Selection of Art and Artist File material from the file of Alma Thomas.

Preservation Services Department

During a normal work week, you can often find our Preservation Services staff at the bench in our Book Conservation Lab repairing materials. Without access to our physical collections, this team has turned digital to advocate for collections care and help explain their work. They’ve presented webinars, answered questions on Instagram and Twitter and, most recently, developed a video series to describe the conservation treatments made possible through our Adopt-a-Book program, “Adopt-a-Book: Preserving Treasures Together”. Many thanks to Keala Richard, Vanessa Smith, Donald Stankavage, Daniel Viltsek and Katie Wagner for sharing their work and participating in our outreach efforts during the pandemic.

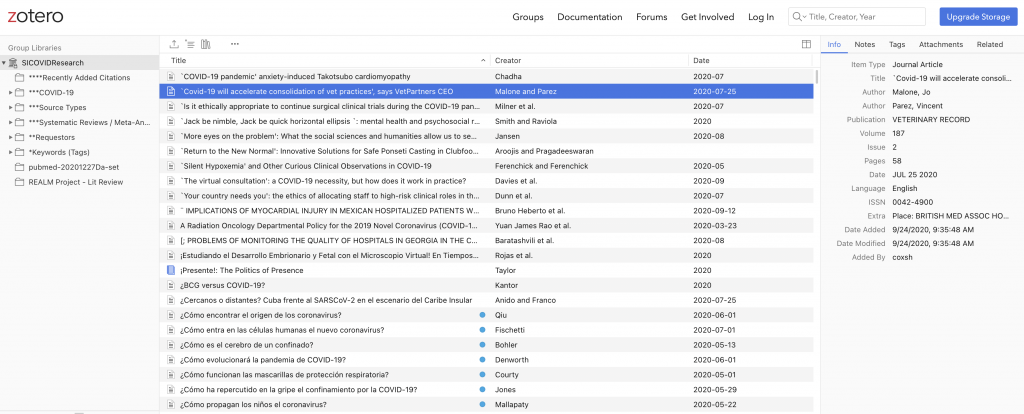

Stephen H. Cox

Branch Librarian, National Zoological Park and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

“Over the past year, I have created and continue to curate and maintain four citation databases on behalf of SI’s COVID-19 task forces: Scholarly Literature, Non-Scholarly Sources, Risk Assessment, and RNA Sequencing. Well over 100,000 scholarly papers, book chapters, books, theses, and reports have been written in the span of 15 months, with thousands more being published every day. Within Scholarly Literature, I have focused research on air monitoring, breather/exhalation valves, face coverings, contact tracing, safety training, surface wipe sampling, and temporal patterns in viral load. Despite the evolving science on the novel coronavirus and its variants, two constants have emerged: the dedication of the Smithsonian’s COVID-19 task force members to the safety of our colleagues and visitors, and the incredible diversity of knowledge that can be created when the world’s scientists have a shared goal.”

Screenshot of COVID-19 Citation Database in Zotero.

Screenshot of COVID-19 Citation Database in Zotero.

Baasil Wilder

Librarian, Anacostia Community Museum Library and National Postal Museum Library

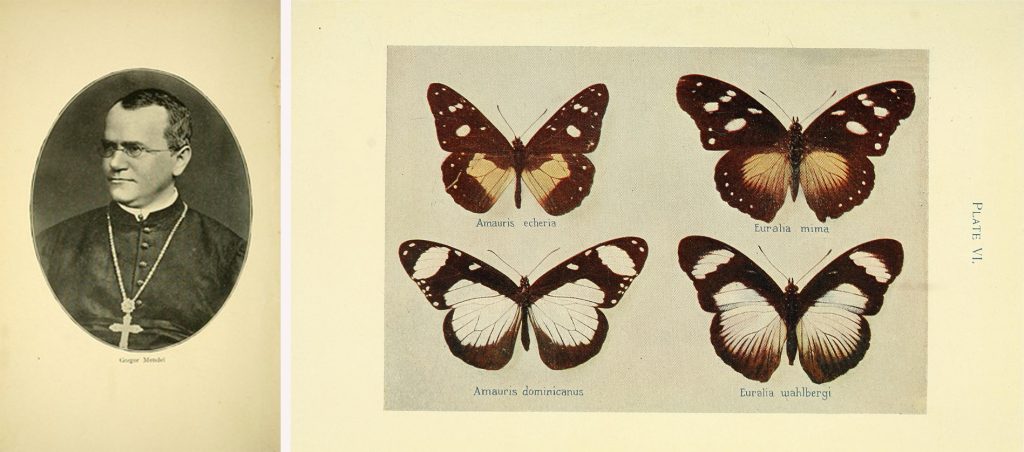

“A team of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives staff has made great progress improving page-level and image-level metadata for digitized books by re-paginating the materials and uploading images to the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s Flickr photostream while working from home (more details in this previous blog post by Alexia MacClain). The work that I do as a member of this team, is a huge leap from what I focused on as a reference librarian before the pandemic . Though different from my usual tasks, this work is all about providing access to information, which is my goal as a librarian. Doing this work has given me a much greater appreciation of what’s happening behind-the-scenes in our Digital Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library. I want to highlight one of my completed Flickr albums, from a book entitled Mendelism (1911). Mendelism is about the principles of genetics, such as single-gene traits, and is named after Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884). Mendel was born in (today’s) Czech Republic and was a meteorologist, mathematician, biologist, Augustinian friar, and the abbot of St. Thomas’ Abbey. He established the laws that are the foundation of the modern science of genetics. Below are some images from the book that I uploaded to Flickr. I rotated them and tagged them with keywords and taxonomic name tags so that users from all over the world can more easily discover and use the free images in their research.”

Portrait of Gregor Mendel and Plate VI, Mendelism (1911).

Portrait of Gregor Mendel and Plate VI, Mendelism (1911).

Graceanna Lewis: A naturalist and abolitionist

“To her mind the truths of science seem revealed.”

That’s how Phebe A. Hanaford, author of Daughters of America (c. 1882), described naturalist Graceanna Lewis, one of the first three woman to be accepted into the Academy of Natural Sciences. But Lewis was not only one of the first professionally acknowledged women naturalists; she was also an abolitionist and social reformer who worked for the advancement of science as well as human rights. Researchers can find many publications by and about this intriguing woman in the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Digital Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Born in 1821, Lewis benefitted from an egalitarian Quaker upbringing, one that encouraged education in daughters as well as sons. Lewis told Hanaford that she learned to love natural history from her mother, Esther Lewis. Esther had been a teacher before marriage and continued to educate her own young children, sending her daughters to nearby Kimberton Boarding School as they grew. There, Graceanna was influenced by Abigail Kimber, a woman botanist who had discovered and identified several species. In 1842, Lewis’ uncle, Dr. Bartholomew Fussell, started a new boarding school for girls, and Lewis came on board as a teacher. She taught astronomy and botany, among other subjects.

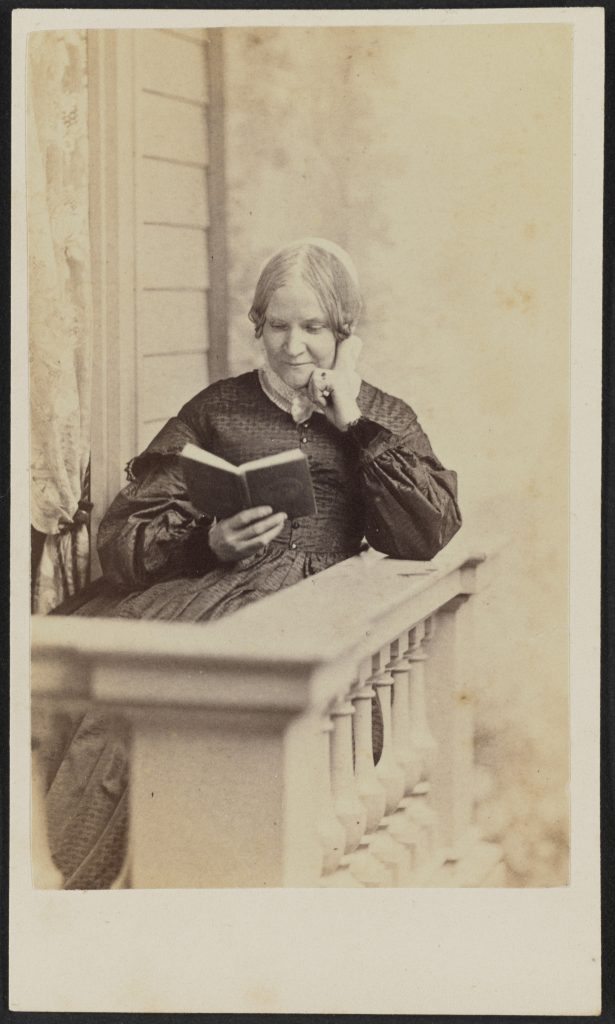

Portrait of Graceanna Lewis, The Underground Rail Road (1872)

Portrait of Graceanna Lewis, The Underground Rail Road (1872)

From her family, Graceanna Lewis inherited not only an interest in science and education but also a deep concern for social issues. Uncle Bartholomew was an active abolitionist, and the family formed a local auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Lewis sisters, Graceanna, Mariann and Elizabeth, were profiled in William Still’s The Underground Rail Road (1872), which described them as “among the most faithful, devoted, and quietly efficient workers in the Anti-slavery cause”.

One of Graceanna’s earliest publications, written in the 1840s, was “An Appeal to Those Members of the Society of Friends Who Knowing the Principles of the Abolitionists Stand Aloof from the Anti-Slavery Enterprise”. It implored fellow Quakers to join the Anti-Slavery movement. The Lewis farm in Pennsylvania became a frequent and successful point on the Underground Railroad, described in detail by Still. The family helped transport those seeking freedom and provided clothes and supplies.

Eventually, Lewis moved away from the family farm to Philadelphia. She had studied birds and other natural sciences on her own, but this move allowed her to take advantage of the specimen and library collections at the nearby Academy of Natural Sciences, and it propelled her into a network of naturalists. In 1862, she met John Cassin, ornithologist and curator of birds at the Academy. Cassin had written, with George N. Lawrence and the Smithsonian’s own Spencer Baird, The Birds of North America (1860), a work Lewis found particularly inspiring.

Cassin would be an invaluable friend and mentor to Lewis, even naming a bird for her, Icterus graceannae, the White-edged oriole. Lewis also corresponded frequently with Baird for years, seeking advice and asking for copies of Smithsonian publications. In 1870, the year after Cassin’s death, Lewis became one of the first three women admitted as members to the Academy.

Icterus graceannae, or White-edged Oriole, Ibis. Series 5, Volume 1. No. 1-4. Plate XI.

Icterus graceannae, or White-edged Oriole, Ibis. Series 5, Volume 1. No. 1-4. Plate XI.

Lewis had channeled her interested in ornithology into her first scientific publication, Natural History of Birds : lectures on ornithology, in ten parts (1868). It was intended as an inexpensive overview of American birds for a general audience. In it, she also proposed a new classification scheme based on embryology, the characteristics of eggs. Unfortunately, only the first part was published, as funding for the remaining nine was never secured. She continued to research and publish on birds, alongside the leading naturalists of her time. Her articles in The American Naturalist, “The Lyre Bird” (August 1870) and “Symmetrical Figures in Birds’ Feathers” (November 1871) are available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

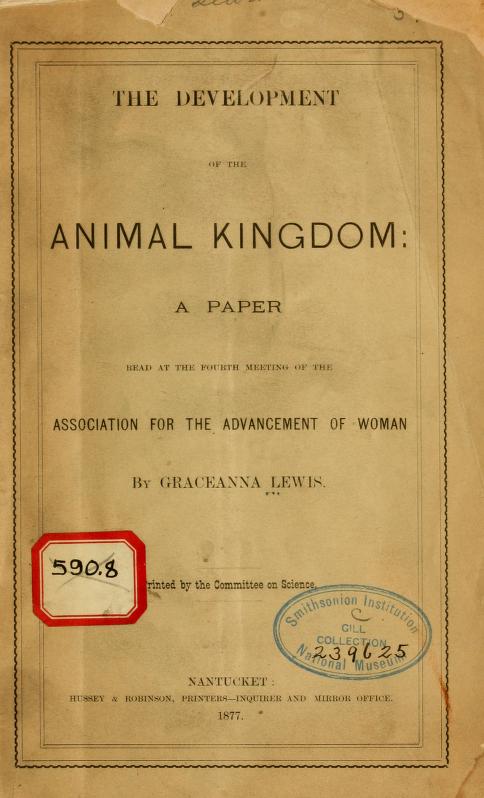

Lewis’ interests and publications grew beyond ornithology, into the classification of natural history and a “tree of life”, which she exhibited at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876. The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877), available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library, is a twenty-page overview of her theories. It was prepared for the fourth meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Women. The group was formed in 1868 with the goal of presenting practical methods for improving women’s role in society, including education on a variety of subjects. Unsurprisingly, Lewis was active on the group’s Committee on Science.

Cover, The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877).

Cover, The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877).

Lewis told Phebe A. Hanaford in 1882, “I feel that my life’s work is before me, in lecturing on zoology to girls just blooming into womanhood”. For the next twenty years, Lewis continued to teach and write about various natural history topics. Her article “On the Genus Hyliota”, discussing the distinction of two rare African birds, was published in The Annals and magazine of natural history in 1883. Her social reform interests turned to temperance and suffrage, serving stints as secretary for her local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and suffrage association.

Graceanna Lewis died in 1912 in Media, Pennsylvania at the age of 90. Her contributions to both science and social progress leave a remarkable and inspiring legacy.

Further Reading from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives:

Baird, Spencer Fullerton, John Cassin and George N. Lawrence. The Birds of North America (1860).

Baird, Spencer Fullerton. Spencer Fullerton Baird Papers. Record Unit 7002. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Hanaford, Phebe A. Daughters of America (1883).

Lewis, Graceanna. The Development of the Animal Kingdom (1877).

Lewis, Graceanna. “On the genus Hyliota”. The Annals and magazine of natural history, Series 5, Volume 12, No. 67, pp. 210-212.

Still, William. The Underground rail road (1872).

Warner, Deborah Jean. Graceanna Lewis, scientist and humanitarian (1979).

Other resources:

Bonta, Marcia. “Graceanna Lewis, Portrait of a Quaker Naturalist”. Quaker History, Volume 74, Number 1, Spring 1985, pp. 27-40.

Lewis-Fussell Family Papers, SFHL-RG5-087, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

Lewis, Graceanna. “An appeal to those members of the Society of Friends who knowing the principles of the abolitionists stand aloof from the anti-slavery enterprise”. [between 1840 and 1849?].

Lewis, Graceanna. “The Lyre Bird” The American Naturalist (August 1870), pp 321.

Lewis, Graceanna. “Symmetrical Figures in Birds’ Feathers” . The American Naturalist (November 1871), pp. 675-678.

Truitt, James. “Digitizing the Papers of Graceanna Lewis, Ornithologist and Activist”. Cassinia. No. 77 (2017-2018), pp. 40-41.

Leisure Activities from the Past: Clues from the Trade Literature Collection

As winter winds down and spring approaches, outdoor activities start to look more appealing. How did people a 100 years ago spend their free time outside? The National Museum of American History Library’s Trade Literature Collection offers a few clues to some very recognizable pastimes.

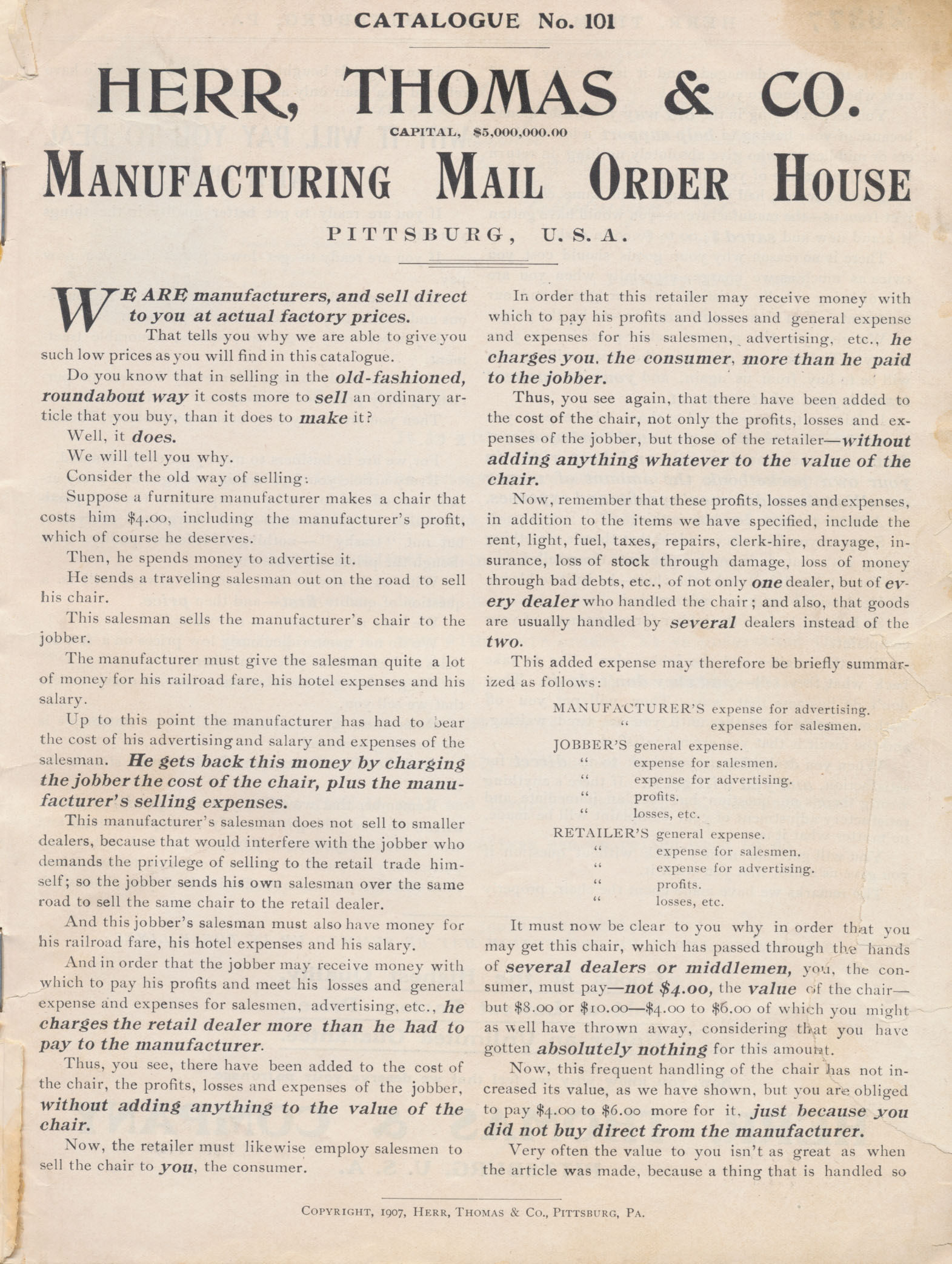

Let’s take a look at two trade catalogs from the early 20th Century. One is from 1907 and the other is from 1915. The first trade catalog is titled Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. As highlighted in previous posts, this particular catalog advertises a variety of products such as furniture and writing supplies as well as toys, musical instruments, and jewelry. But there is so much more. It also includes a few pages focused on recreation and outdoor activities appropriate for all four seasons.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.A winter activity some enjoy today is sledding. Judging from the fact that Catalogue No. 101 (1907) advertises sleds, children in the early 20th Century probably also enjoyed that activity. From this catalog, we gain a glimpse into the types of sleds they might have used. A page from the toy section, shown below, illustrates three sleds.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), front cover [page 1], explanation of benefits of buying direct from the company.A winter activity some enjoy today is sledding. Judging from the fact that Catalogue No. 101 (1907) advertises sleds, children in the early 20th Century probably also enjoyed that activity. From this catalog, we gain a glimpse into the types of sleds they might have used. A page from the toy section, shown below, illustrates three sleds.

One sled was called the Flexible Flyer. It featured the ability to steer without decreasing speed. This was accomplished by applying just a slight pressure on the cross bar. Another sled, the Clipper Sled, was made of hardwood with steel runners. It included four hand grips to hold onto while coasting down hills. Two hand grips were positioned on each side of the runners. The seat of the sled was decorated with a design incorporating a ship. The third sled, simply labeled a “Sled” in the catalog, featured full-length hand rails on each side. It also conveniently came with a foot rest. The foot rest was positioned between the curved front pieces. Iron swan heads adorned the top of the curved front pieces which also held the guiding rope. According to this catalog, the seat of the sled was decorated in five colors but does not mention specific colors.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 85, Automobile, Wagons, Sleds, Printing Press, Child’s Tea Set, and Boy’s Tool Chest.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 85, Automobile, Wagons, Sleds, Printing Press, Child’s Tea Set, and Boy’s Tool Chest.

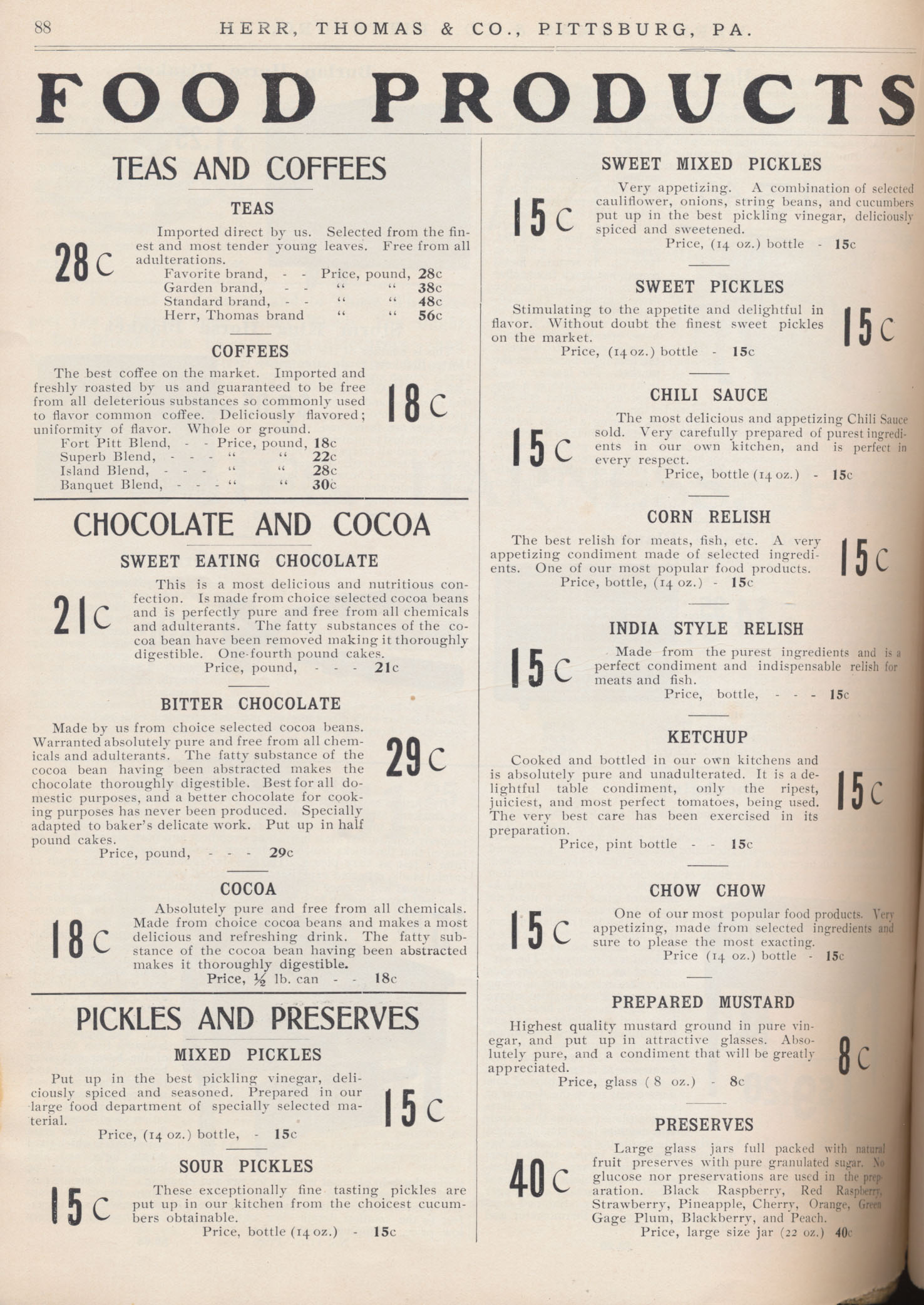

After an afternoon spent outdoors sledding, cocoa might have been a pleasant surprise. Herr, Thomas & Co. also sold food and grocery products. This included cocoa and “sweet eating chocolate.” Bitter chocolate for cooking purposes, tea, coffee, pickles, and preserves are also described in this catalog.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 88, Food products (teas, coffees, chocolate, cocoa, pickles, preserves).

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 88, Food products (teas, coffees, chocolate, cocoa, pickles, preserves).

What about outdoor activities during spring, summer, and fall? Herr, Thomas & Co. trade literature also provides clues as to what people in 1907 possibly enjoyed during the warmer months. These activities might sound familiar to us today as well. The page below shows two hammocks. Perhaps someone enjoyed an afternoon reading a book or simply resting on a hammock. The hammocks shown below were woven with cotton yarn and available in green, yellow, or red. An added bonus for comfort was the roll pillow. The hammock shown below, middle left, was a bit more decorative due to the 15 inch deep valance.

Consumers in 1907 also had the option of buying a simple lawn chair for their backyard. The striped Lawn Chair (below, top right) was foldable. Its frame was made of hardwood. The Lawn Chair was also adjustable to either a sitting or reclining position. Other possibilities for relaxing outside in the garden included the Reed Tete and Lawn Settee, both shown below.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 69, Lawn and Porch Furniture (Reed Tete, Lawn Chair, Hammocks, Lawn Settee) and Sporting Goods (Spaulding Striking Bag, Spaulding Catchers’ Glove).

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 69, Lawn and Porch Furniture (Reed Tete, Lawn Chair, Hammocks, Lawn Settee) and Sporting Goods (Spaulding Striking Bag, Spaulding Catchers’ Glove).

Another idea for a relaxing afternoon is resting on a Porch Swing. The Porch Swing, shown below (bottom right), featured a slightly curved seat with the convenience of both a foot rest and leg rest. The leg rest extended 17 inches below the seat connecting to a solid foot rest which was covered in linoleum. While adults rested on the porch, perhaps children played in the Lawn Tent (below, bottom left). Maybe the Lawn Tent was a setting for their own tea party using the Child’s Tea Set, also sold by Herr, Thomas & Co. The Lawn Tent was made of cotton duck and measured 8 feet wide, 8 feet long, and 8 feet high.

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 68, Lawn Implements (Push Cart, Garden Wheelbarrow, Rubber Hose, Hose Reel, Lawn Mower) and Lawn and Porch Furniture (Lawn Tent, Lawn Swing, Porch Swing).

Herr, Thomas & Co., Pittsburg, PA. Catalogue No. 101 (1907), page 68, Lawn Implements (Push Cart, Garden Wheelbarrow, Rubber Hose, Hose Reel, Lawn Mower) and Lawn and Porch Furniture (Lawn Tent, Lawn Swing, Porch Swing).

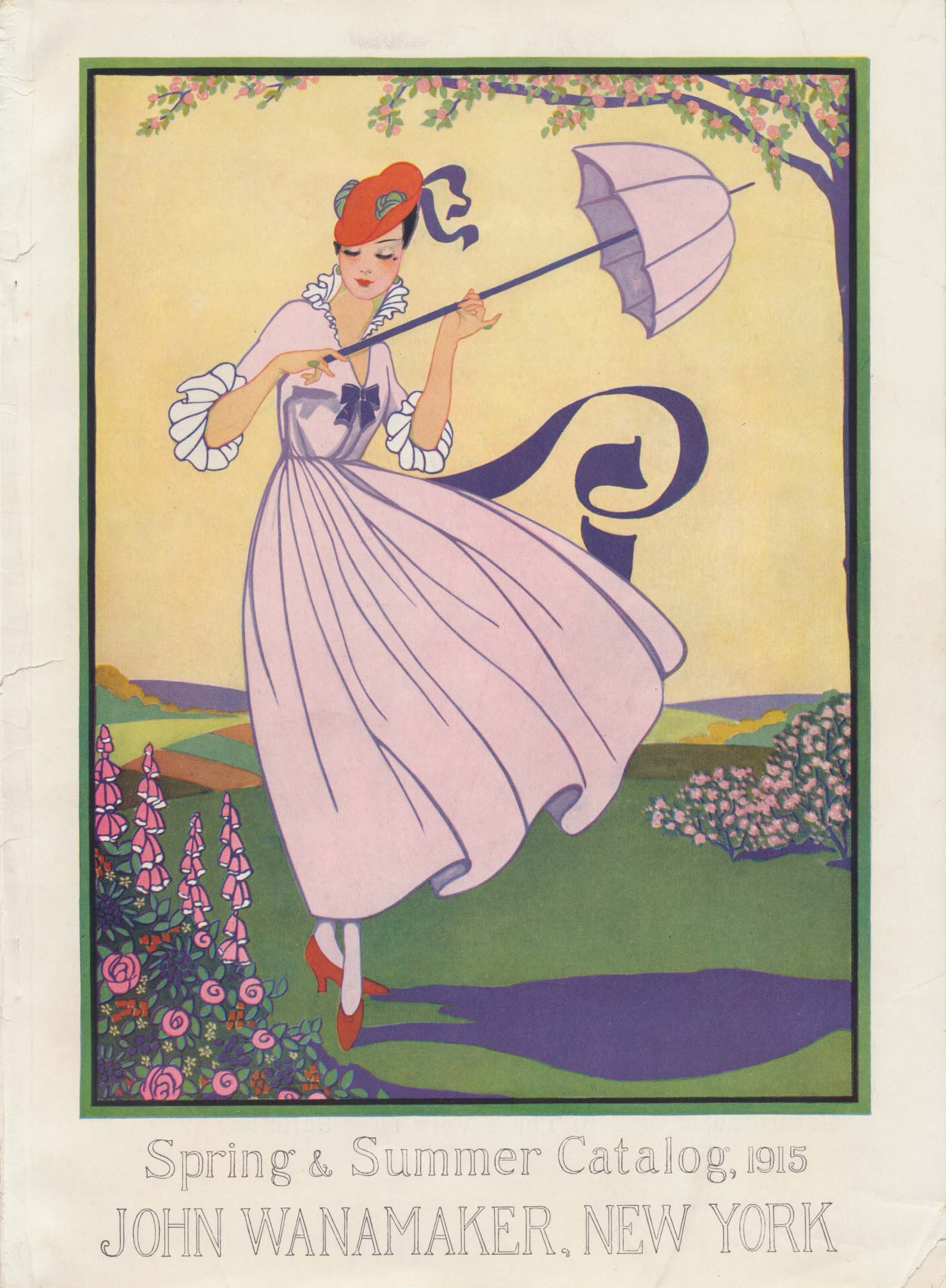

Moving along, a little over a decade later, let’s take a look at Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) by John Wanamaker. As described in a previous post, this particular catalog illustrates clothing. This includes riding habits and other accessories for horseback riding.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), front cover.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), front cover.

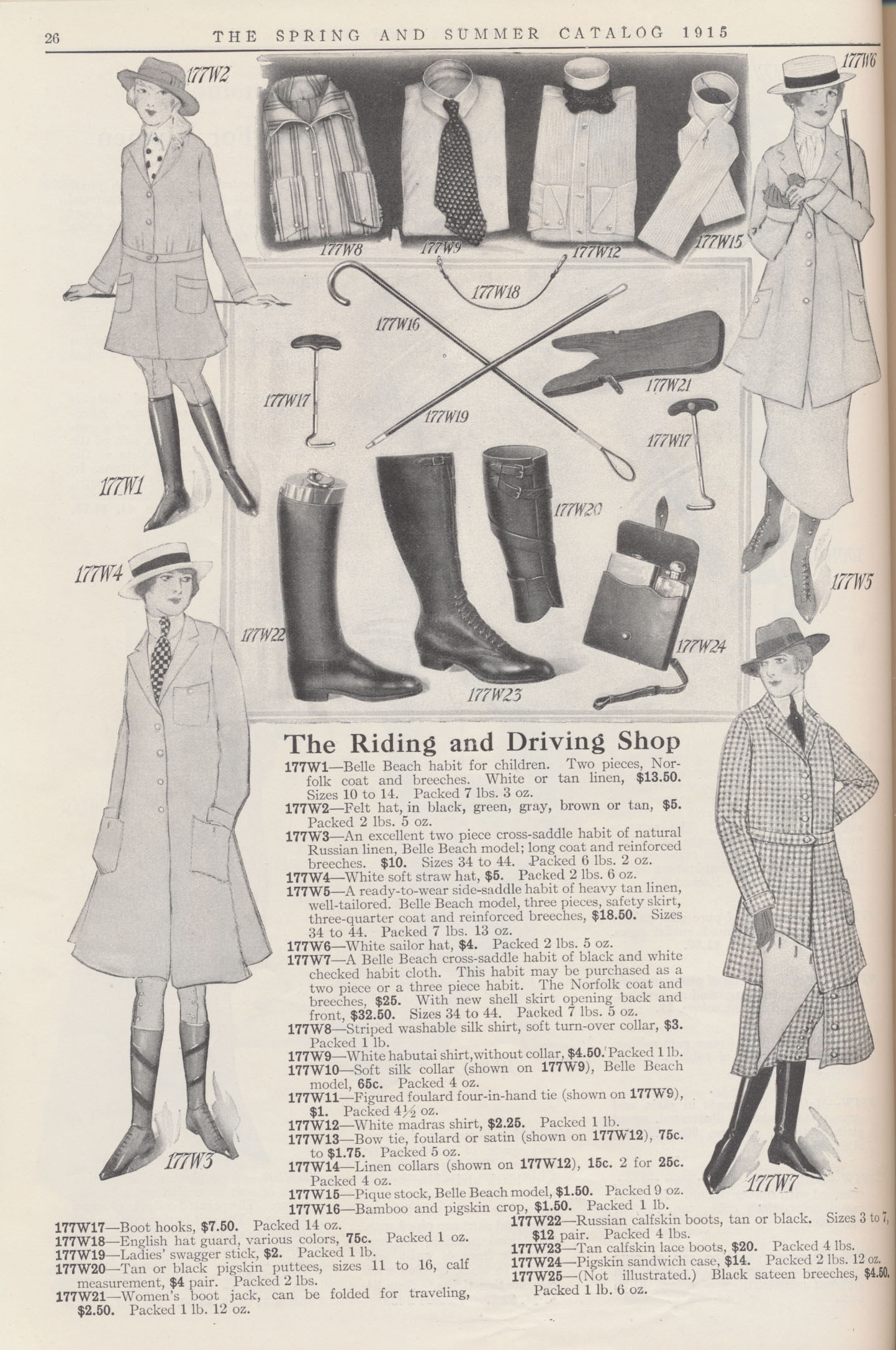

Both side-saddle and cross-saddle riding habits were available. “Cross-saddle”, or astride, refers to the more common type of saddle used today. The side-saddle habit (below, top right) was a three-piece set made of tan linen. It consisted of a safety skirt, three-quarter coat, and reinforced breeches. As might be expected, the cross-saddle habit pictured below (bottom left) consisted of two pieces, the long coat and reinforced breeches.

However, it was also possible to buy a different cross-saddle habit which came with a skirt. As a two-piece set, it included only a coat and breeches, but with the addition of a shell skirt, it was also available as a three-piece set. The shell skirt opened in the front and back making it a split skirt and providing the ability to ride cross-saddle. This particular riding habit with a black and white checkered pattern is shown below (bottom right). Other riding equipment and accessories illustrated in this catalog include riding boots, shirts, collars, bowties, and hats.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 26, horseback riding habits, equipment, and accessories.

John Wanamaker, New York, NY. Spring & Summer Catalog (1915), page 26, horseback riding habits, equipment, and accessories.

Besides providing clues as to the types of products bought by consumers in the early 20th Century, these trade catalogs also show the types of activities they might have participated in and enjoyed. Catalogue No. 101 (1907) by Herr, Thomas & Co. and Spring & Summer Catalog (1915) by John Wanamaker are both located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Upcoming Events: March and April

We’ll be busy over the next few months and you’re invited. Interested in Women’s History? Want to get a closer look at our collections? Join us for an upcoming event!

Wonderful Women Creating Change

Wednesday, March 10, 5 pm ET

Register here

To celebrate Women’s History Month in March and the recent release of Wonder Woman 1984 (filmed and set at the Smithsonian!), join us for the first in our Women’s History with Smithsonian Libraries and Archives program series, sponsored by Deloitte, “Wonderful Women Creating Change.” You’ll learn about our own connections to this iconic character and hear what it was really like to be a woman working at the Smithsonian in the 1970s and 1980s.

Lilla Vekerdy, Head and Curator of Special Collections, and Elizabeth Harmon, Digital Curator of the History of Smithsonian Women in Science, will share behind-the-scenes insights into the intriguing contents of our collection of materials from the creator of Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston, and our fascinating Smithsonian records that document the experiences of real women.

Thank you to our generous sponsors of this program:

Signature Sponsor: Deloitte

Sponsor: Smithsonian’s Atlanta Regional Council, Co-Chaired by Cheryl Neal and Christine Ragland

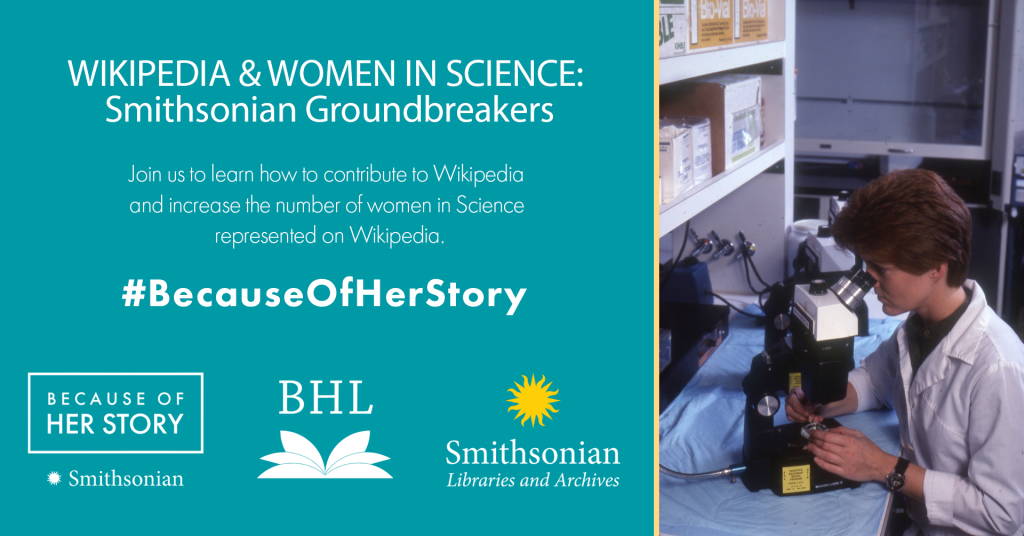

Wikipedia & Women in Science: Smithsonian Groundbreakers Edit-a-thon

Thursday, March 25, 1 pm – 3 pm ET

Register here

There are so many inspiring stories about women in science at the Smithsonian in its 175-year history that can educate and embolden future generations, but only if their legacies are discoverable. On Thursday, March 25, join our #BecauseOfHerStory effort to uncover more about these often underrepresented women trailblazers in various disciplines, from astrophysics to zoology

During this training, attendees of all experience levels will learn the basics of how to edit Wikipedia by updating articles related to the history of women in science at the Smithsonian Institution in connection with the Funk List. Presenters will share how editors might research the work of these women in the absence of personal papers and institutional records.

As one of the web’s most visited reference sites, Wikipedia serves as a starting point for many individuals looking to learn about art, history, and science. However, less than 19% of Wikipedia biographies in English represent women, and less than 10% of Wikipedia editors identify as women. By increasing representation of women scientists on the site, your impact can spark the curiosities of future generations who see themselves in these Smithsonian groundbreakers.

This event is planned in conjunction with the Smithsonian Institution Archives, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, and the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, a multiyear undertaking to document, research, collect, display, and share the history of women in the United States.

Adopt-a-Book Salons with Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

March 18, April 1, April 13, April 28

Registration details below

Get up close and personal with Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ collections and experts through our new series of Adopt-a-Book Salons!

Our Adopt-a-Book program provides essential funding to support conservation, acquisition, and digitization of our materials while allowing you to commemorate an occasion, celebrate a milestone, or leave a legacy for a loved one. Each year, we invite guests to our Adopt-a-Book Evening to explore books available for adoption and learn why these items are crucial for researchers today.

This year, we’ve taken our annual event online and will be hosting a series of four intimate salons in March and April, where you’ll have the opportunity to interact with our librarians, archivists, and conservators. You’re invited to join us for all four events to see books and materials from all 21 of our library branches and the Archives!

Adopt-a-Book Salon: Global Perspectives

Thursday, March 18

5:30 to 6:45 pm ET

Focusing on the global breadth of our collections

Books from Anacostia Community Museum Library, Botany and Horticulture Library, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library, Warren M. Robbins Library at the National Museum of African Art, National Museum of Asian Art Library, National Museum of Natural History Library, Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex, and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Library

Adopt-a-Book Salon: Off the Mall

Thursday, April 1

5:30 to 6:45 pm ET

Featuring an interdisciplinary selection of libraries located off the National Mall

Books from Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Library, Museum Support Center Library, National Air and Space Museum Library, National Postal Museum Library, National Zoological Park Library, and Smithsonian Environmental Research Center Library

Adopt-a-Book Salon: America the Beautiful

Tuesday, April 13

5:30 to 6:45 pm ET

Focusing on American art, history, and culture

Books from American Art and Portrait Gallery Library, John Wesley Powell Library of Anthropology, National Museum of African American History & Culture Library, National Museum of American History Library, Vine Deloria, Jr. Library at the National Museum of the American Indian, and Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex

Adopt-a-Book Salon: From the Vaults

Wednesday, April 28

5:30 to 6:45 pm ET

Featuring special collections, preservation, and the Smithsonian Institution Archives

Books from Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History, and the Smithsonian Institution Archives

Adopt-a-Book Salon Ticket Information

$35 per person, per event. Purchase tickets here.

We’re offering a discount if you attend multiple events: $60 for two events (save $10), $85 for three events (save $20), and $115 for four events (save $25).

If you are unable to attend, please consider adopting a book online or making a donation.

We are committed to providing access services so all participants can fully engage in these events. Optional real-time captioning will be provided. If you need other access services, please email SLA-RSVP@si.edu. Advanced notice is appreciated.

Questions? See our FAQs at the bottom of this page.

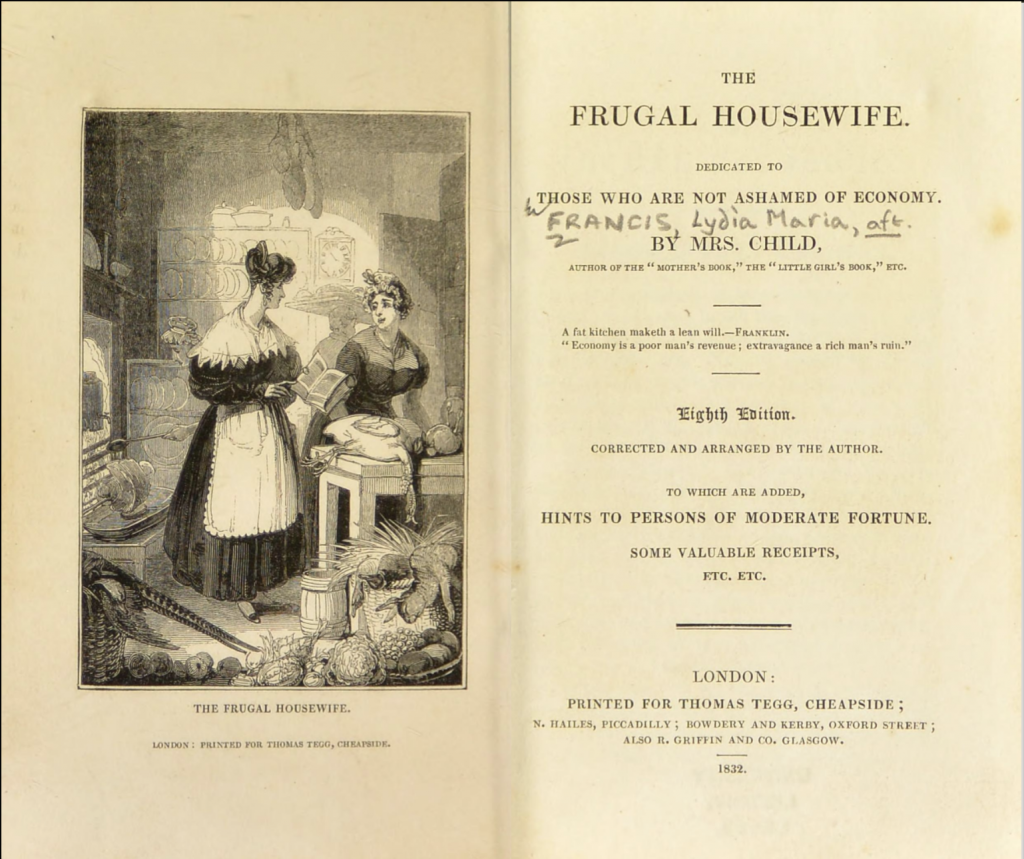

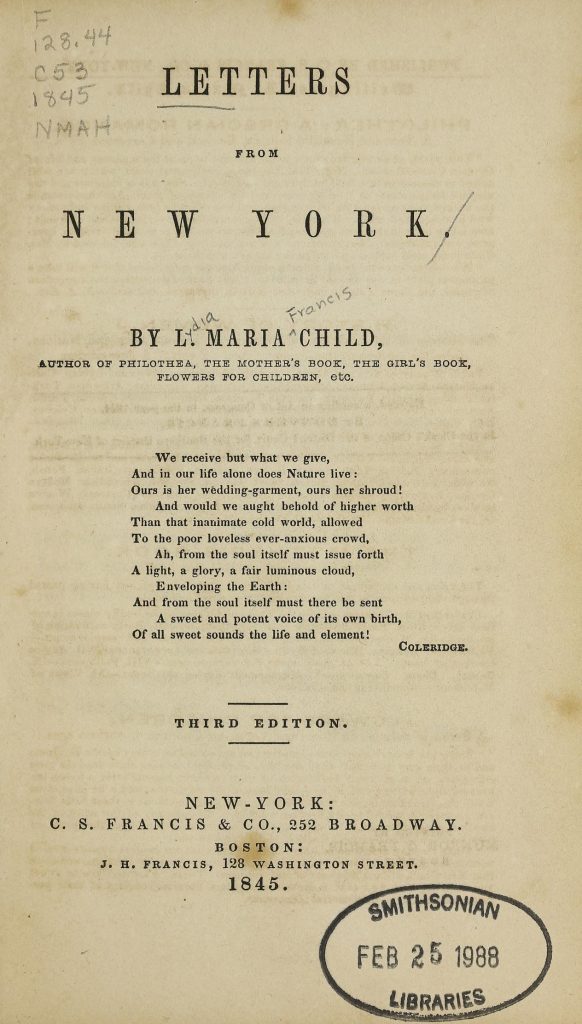

Freer’s Marginalia and Mandarin Ducks

Title page of An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art.

Title page of An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art.

In 1906, industrialist Charles Lang Freer gave his collection of Asian and American art and related materials in a gift that began the Freer Gallery of Art. This gift included books which are now in the Freer-Sackler Library . Among them, some that contain Freer’s personal notes and marginalia. One of these is a first edition copy of Herbert Giles’ book An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art. This book, originally published in 1905, was the first to provide a comprehensive history of Chinese painting in a European language. Freer made margin notes throughout the book, which help show his personal interests as he was building his art collection. His copy of this book has been digitized by the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and can now be examined online.

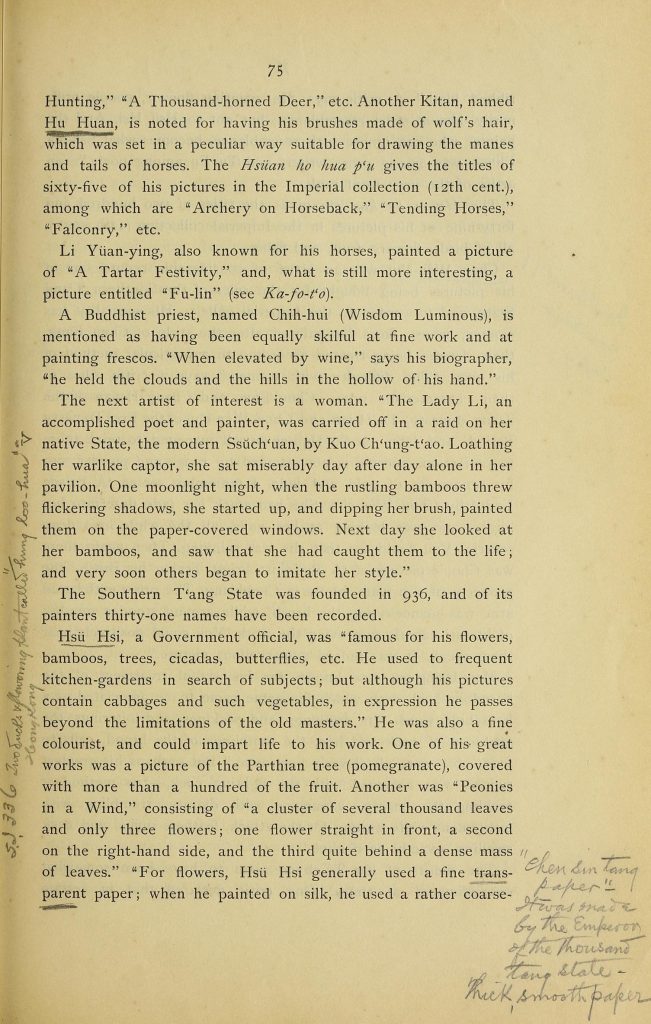

An example of Freer’s notes can be found on page 75. Here Freer has underlined “Hsu Hsi” (Xu Xi), a Five Dynasties Southern Tang (tenth century) Chinese painter, and has written in the left margin: “Two ducks + flowering plant called ‘hung-loo-hua’ Hong Kong.” This seems to be a reference to the painting “Mandarin Ducks under Smartweed” which Freer purchased in 1909 from a Hong Kong dealer. Freer believed the painting to be by Xu Xi, although it is now known to be a Ming Dynasty reproduction.

Page 75 of An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art (1905) with marginalia by Charles Lang Freer. Click to enlarge.

Page 75 of An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art (1905) with marginalia by Charles Lang Freer. Click to enlarge.

On the same page in the lower right hand corner, Freer has underlined the word “transparent” relating to a type of paper on which Xu Xi painted flowers. He has written: “Chen Sin Tang paper” — it was made by the Emperor of the Thousand Tang State. Thick, smooth paper.” This is a reference to a type of Chinese paper that originated in the Five Dynasties Southern Tang that became much sought after in the Northern Song Dynasty. Over the centuries an air of legend and mystery came to surround Chengxin Tang paper, such that in the Qing Dynasty the Qianlong Emperor made it a project to try to recreate it.

“Mandarin Ducks under Smartweed”, detail. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. F1909.192.

“Mandarin Ducks under Smartweed”, detail. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. F1909.192.

As the digitization of Freer’s books continues, more of the marginalia contained in them will be available for online research.

Reference:

He, Yan-chiuan. Chengxin Tang Paper and the Qianlong Emperor: With a Discussion of His Connoisseurship of Ancient Paper. The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 33:1 (2015).

Thank you to Freer and Sackler Archivist Ryan Murray for his reference assistance.

Four New Members Join Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board

The Smithsonian Institution’s Board of Regents appointed John Chickering, Christopher Clark, Christopher Lee and Nick Santhanam to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board. They join 13 prominent community and business leaders dedicated to building the Libraries and Archives’ collections, increasing digital initiatives, advancing education, progressing library and archival preservation, creating high-quality exhibitions and programs and securing a financial legacy.

“It is my pleasure to welcome four outstanding new members to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board,” said Scott E. Miller, interim director of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and the Smithsonian’s chief scientist. “Invaluable leaders in their fields, their experience and guidance will tremendously benefit the Libraries and Archives’ continued growth as a critical global resource. We are fortunate to tap into their extensive wisdom and diverse perspectives.”

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board consists of members from across the United States. The mission of the board is to help the organization to provide authoritative information, steward the Smithsonian’s institutional memory and create innovative services and programs for Smithsonian researchers, scholars, scientists, curators, archivists, historians and other staff, as well as the public at large.

Please join us in welcoming our newest Advisory Board members!

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member John Chickering

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member John Chickering

John Chickering

John Chickering advises boards and senior executives on strategy, technology and operations. He has a track record of effectively bridging business operations and information technology to deploy diverse digital transformation solutions across large enterprises.

As a pioneer in the development of digital archiving solutions, Chickering’s work was cited in industry trade press and he wrote papers for peer-review publications. For the Department of Defense, he defined a system to store over 100 million engineering drawings across dozens of domestic sites.

For Fidelity Investments, he deployed a cross-enterprise digital archive solution. While serving as a chief information officer in Fidelity’s private equity portfolio, Chickering built out the technology for a corporate off-site records storage facility and was a principal thought leader informing Fidelity’s digital records archive strategy. He led a multi-year enterprise digital transformation initiative that migrated complex high-volume customer communications from paper to eDelivery.

Chickering’s board experience includes both fiduciary and advisory boards for commercial, educational and other non-profit institutions where he has held various executive committee positions, including chair. He is a Fellow of the Association for Intelligent Information Management and is an occasional speaker at industry conferences and seminars hosted in academia.

Chickering volunteers with several community service organizations and has led over 15 hurricane/storm restoration work teams on the ground in Mississippi, New York, Vermont and Florida. He holds a Bachelor of Science in marine engineering from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and an MBA from the University of Maryland.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Christopher Clark

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Christopher Clark

Christopher Clark

Christopher York Clark joined Directorship as senior vice president and publisher in December 2002. In 2006, he was promoted to president and publisher of Directorship Services LLC. As senior director of Partner Relations and Publisher, he is presently responsible for the revenue development and conduct of NACD Directorship Magazine, NACD corporate governance forums and director roundtables. In addition, he currently heads the programming for NACD’s Leading Minds of Compensation Forum and NACD’s Leading Minds of Governance Conference. Further, he is the creator of NACD Private Company Directorship and the architect and day-to-day catalyst of NACD’s Power of Difference program.

Clark joined NACD following a decade of service at Forbes Inc. Most recently, he was vice president, sales for Forbes.com. Earlier he served as vice president and general manager of the Forbes Management Conference Group, a leading producer of senior-executive meetings. In this capacity, he oversaw P&L, sales, marketing, program development and logistics for all Forbes conferences. Prior to that position, he served as Forbes magazine’s financial services advertising director.

Presently, Clark is a member of the Broadridge Virtual Shareholder Meeting Best Practices Working Group, and a contributing member of NACD’s Flag and General Officer Advisory Council. He received a Bachelor of Arts from Denison University. In 2006, he was promoted to president and publisher of Directorship Services LLC. As senior director of Partner Relations and Publisher, he is presently responsible for the revenue development and the marketing of NACD Directorship Magazine, NACD corporate governance forums and custom roundtables. In addition, he currently heads the programming for NACD’s Leading Minds of Compensation Forum and NACD’s Leading Minds of Governance Conference and serves as host and moderator at both events. Further, he is the architect and day-to-day catalyst of NACD’s Power of Difference program.

Clark joined NACD following a decade of service at Forbes Inc. Most recently, he was vice president, sales for Forbes.com. Earlier he served as vice president and general manager of the Forbes Management Conference Group, a leading producer of senior-executive meetings. In this capacity, he oversaw P&L, sales, marketing, program development and logistics for all Forbes conferences. Prior to that position, he served as Forbes magazine’s financial services advertising director.

Presently, Clark is a member of the Broadridge Virtual Shareholder Meeting Best Practices Working Group, and a contributing member of NACD’s Flag and General Officer Advisory Council. He received a Bachelor of Arts from Denison University.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Christopher Lee

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Christopher Lee

Christopher Lee

Chris Lee is a partner at FAA Investments, a private investment group focusing on real estate, early-stage companies and in-depth research on hedge funds and private equity managers. With home bases in San Francisco and Hong Kong, Lee and his partners allocate capital globally. He is fluent in English and Chinese.

Additionally, Lee is a board director with expertise in financial markets, risk management, governance and leadership development. Currently, he serves as an Independent Board Member with Matthews Asia Funds, the largest US Investment Company (’40 Act) with a dedicated focus on Asia Pacific markets.

Previously, Lee was an investment banker for 18 years, acting as managing director and divisional and regional heads at Deutsche Bank AG, UBS Investment Bank AG and Bank of America Merrill Lynch. He worked in global capital markets, managed derivative product development and provided equity sales and trading functions to institutional investors.

He is an advocate of sustainable enterprises and environmentally conscious projects, serving on various boards with a passion for promoting education, conservation, energy efficiency and sustainability. Lee also serves on the boards of University of California, Berkeley-Haas Dean’s Advisory Circle, African Wildlife Foundation, Hong Kong Securities and Investment Institute and Salzburg Global Seminar.

Academically, Lee is an associate professor of science practice at HKUST and teaches financial mathematics and risk management courses. He completed the AMP at Harvard University and holds a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering and an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Nick Santhanam

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board Member Nick Santhanam

Nick Santhanam

Nick Santhanam is a senior Partner in McKinsey & Company’s Silicon Valley Office and leads their global industrials practice. Nick also leads their S5C (Sub $5 billion companies) practice. Nick serves industrials/industrial-tech companies on their end-to-end strategy and performance transformation efforts. He has led their work on “McKinsey on industrials,” “McKinsey on Packaging,” “McKinsey on flow control,” “McKinsey on food processing and handling,” “McKinsey on construction” and several other knowledge efforts, which are deep dives in various industrial micro verticals, to map the secular growth headwinds and tailwinds as well as what it takes for companies to create and capture value. He also hosts their annual CEO summits—Industrial CEO (GILS), Tech CEOs (T-30), Family-owned companies CEO (L-20)—as well as he the host and convener of their executive learning programs including board learning event on disruptions (NWDS), investor learning on disruptions (NWDS-I) and executive learning event on transformations (APT-30). In the past 36 months, he has led multiple successful transformations of companies, which has led to 200-500 basis points of margin expansion and significant shareholder value creation.

Prior to joining McKinsey, Santhanam worked as a technical manager at Taconic (a PCB/ceramics manufacturer), Petersburgh, New York. Prior to Taconic, he worked as a manufacturing engineer at Arlon in their Bear, Delaware facility.

Santhanam has a Master of Science in chemical engineering from University of Illinois and an MBA in strategic management and finance from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. He graduated as a Ford and Palmer scholar from Wharton.

John Wesley Cromwell and the Importance of Representation

John Wesley Cromwell was an influential African American lawyer, educator and activist. He was also an early advocate for a concept librarians and educators still struggle with today: representation of historically marginalized voices in American literature.

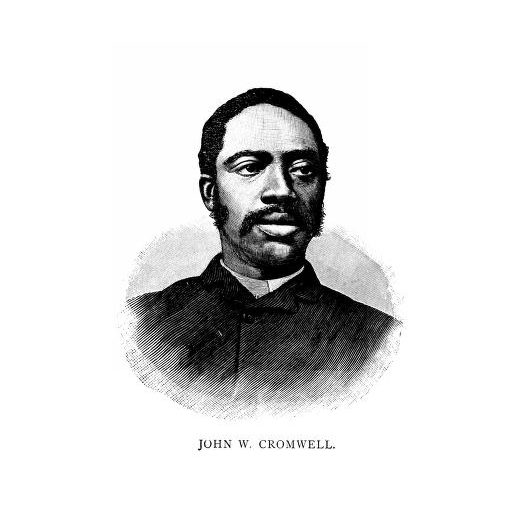

Portrait of John Wesley Cromwell, from Men of Mark (1887) . Courtesy of Emory University, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, accessed via Internet Archive.

Portrait of John Wesley Cromwell, from Men of Mark (1887) . Courtesy of Emory University, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, accessed via Internet Archive.

Cromwell was born enslaved in Virginia in 1846, the youngest of seven children. His father was able to obtain freedom for the family and relocated to Pennsylvania during John’s childhood. Cromwell attended school in Philadelphia, graduating from the Institute for Colored Youth, and soon took up teaching in Virginia. He moved to D.C. and graduated from Howard University Law School in 1874. Cromwell held several civil service jobs and practiced law for over a decade while maintaining positions in African American educational organizations and publishing his own paper, People’s Advocate.

Cromwell’s contributions were significant enough in the late 19th century that William J. Simmons profiled him in Men of Mark (1887) alongside notable figures like Frederick Douglass and Crispus Attucks. Simmons claimed, “If you ask me for the best English scholar in the United States, I would unhesitatingly refer you to John Wesley Cromwell.” Cromwell helped form the American Negro Academy in 1897, an organization dedicated to the advancement of African Americans in higher education, arts and sciences.

Between his teaching career and his deep interest in literature, Cromwell identified a hole in American education, one in which African American children “learn little or nothing of their kith or kin that is meritorious or inspiring”. He sought to address this issue of representation in his book The Negro in American History, published in 1914 by the American Negro Academy. When it was published, the Journal of Negro History reviewed it as a “very important work”.

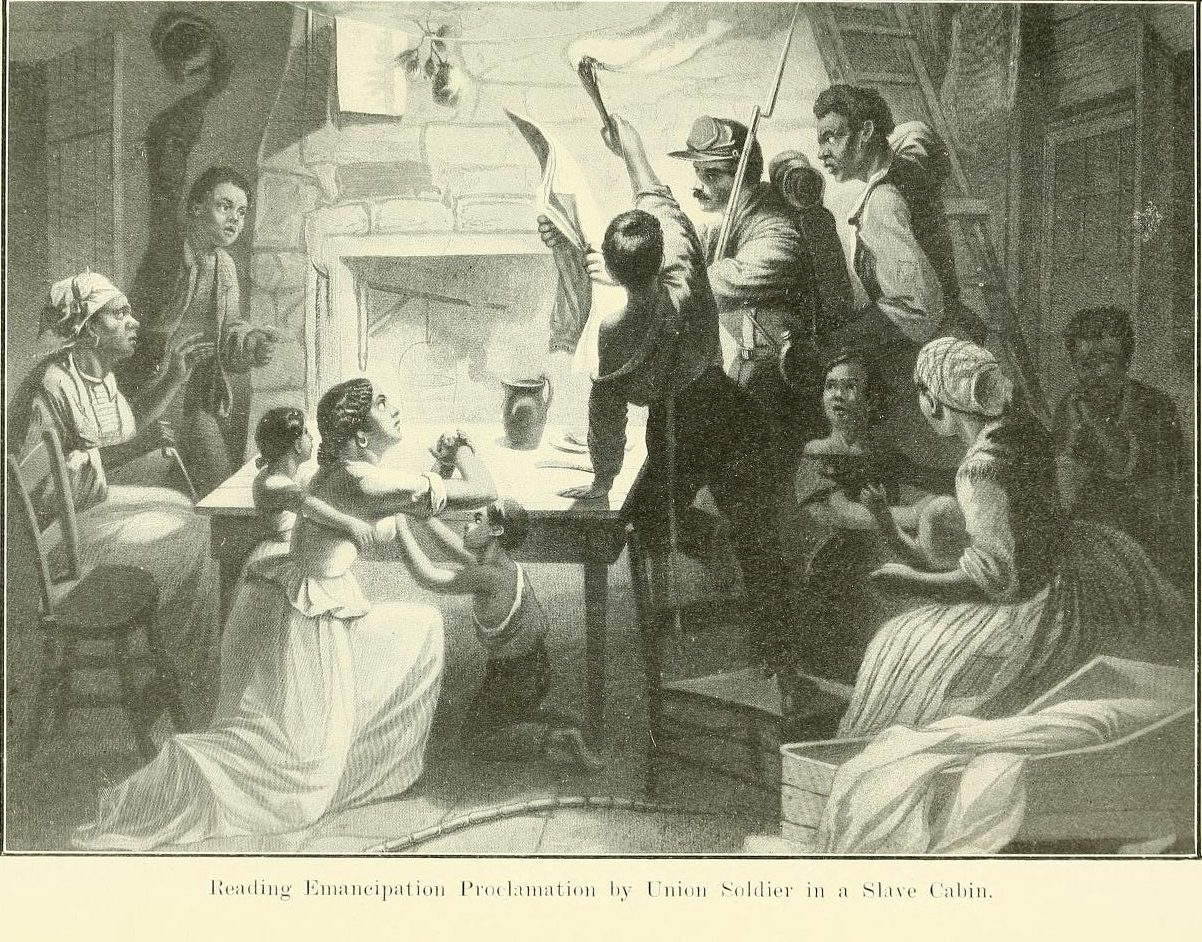

“Reading Emancipation Proclamation by Union Soldier in a Slave Cabin”, plate from The Negro in American History (1914).

“Reading Emancipation Proclamation by Union Soldier in a Slave Cabin”, plate from The Negro in American History (1914).

The book, available in our Digital Library, describes the involvement of Black men and women in many areas of American history, from colonization through the Spanish-American War and beyond. It also discusses African American culture in chapters like “Negro Church”. Much of the book profiles remarkable Black men and women. Some are still household names: Benjamin Banneker, Sojourner Truth, and Booker T. Washington. But others are not as well known. Fanny Muriel Jackson Coppin was a skilled orator and educator who was also the first African American woman to graduate from a recognized college. Robert Brown Elliott was a Reconstruction era lawyer and politician who helped draft legislation to fight the Ku Klux Klan in the South.

Cromwell provided the introduction for another book related to African American representation in history, Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture (1916). Freeman Henry Morris Murray’s self-published book, part of his Black Folk in Art series, investigates how the enslaved were depicted in sculpture, from Hiram Power’s “Greek Slave” to proposed plans for the Lincoln Memorial. In his introduction, Cromwell notes that Murray was compelled to pursue the subject after observing “omissions of proper representation of the darker races”. An observation Cromwell could certainly relate to.

Cover, Emancipation and the freed in American sculpture (1916).

Cover, Emancipation and the freed in American sculpture (1916).

Over a hundred years after the publication of Cromwell’s The Negro in American History, educators and librarians continue to work towards fair representation in literature, seeking out stories that tell the experience of all Americans. The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ newest exhibition, Magnificent Obsessions: Why We Collect, highlights the importance of building collections at the Vine Deloria Jr. Library, National Museum of the American Indian and the Anacostia Community Museum Library that represent the diverse communities they serve. Our staff continue to work with curators and researchers across the Smithsonian to acquire books, journals and other resources with diversity, equity and inclusion in mind. The problem John Wesley Cromwell identified is unfortunately far from solved, but his legacy lives on.

Further Reading:

Cromwell, Adelaide M., Unveiled Voices, Unvarnished Memories: the Cromwell Family in Slavery and Segregation, 1692-1972.

Zhong Kui and the Chinese New Year

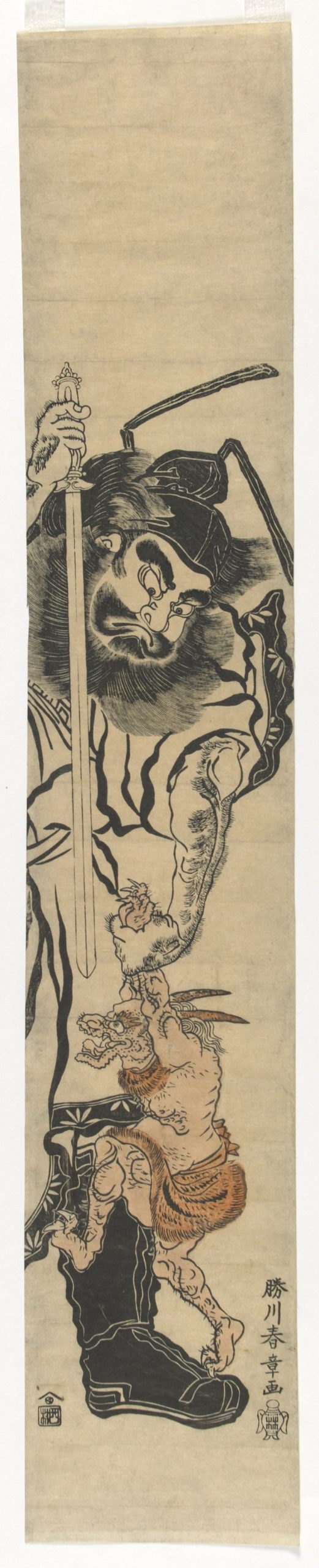

Shoki (Zhong Kui) Vanquishing a Demon, Katsukawa Shunsho (1726–1792), Japan, Edo period, early 1770s, woodblock print, ink and color on paper, The Anne van Biema Collection, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S2004.3.323.

Shoki (Zhong Kui) Vanquishing a Demon, Katsukawa Shunsho (1726–1792), Japan, Edo period, early 1770s, woodblock print, ink and color on paper, The Anne van Biema Collection, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S2004.3.323.

Zhong Kui is a legendary figure in East Asian countries. In China, it is customary that by the end of the year in preparation for the New Year, people hang his portrait on their doors as he is the auspicious spirit that protects people from demons and cures incurable diseases.

Zhong Kui was first mentioned in Dream Pool Essays by Song author Shen Kuo (1031-1095). He recounts how Zhong Kui entered a military examination where people would be judged on their military skills and then possibly selected to serve in the country’s military. Despite Zhong Kui’s outstanding performance, he was eliminated due to his unconventional appearance. He was regarded as grotesque looking. Zhong Kui was so upset with the injustice of his rejection that as a form of protest, he committed suicide.

Then, one day, an ailing emperor, Xuanzong of Tang (685-762) had a dream in which Zhong Kui killed the evil–spirited ghost who sickened him. The next day, the emperor felt healthy and well. He ordered the great Tang painter Wu Daozi (680-760) to paint a portrait of Zhong Kui and issued an imperial edict to have his subjects hang Zhong Kui’s portrait at the New Year. A tradition was born and Zhong Kui became a legend.

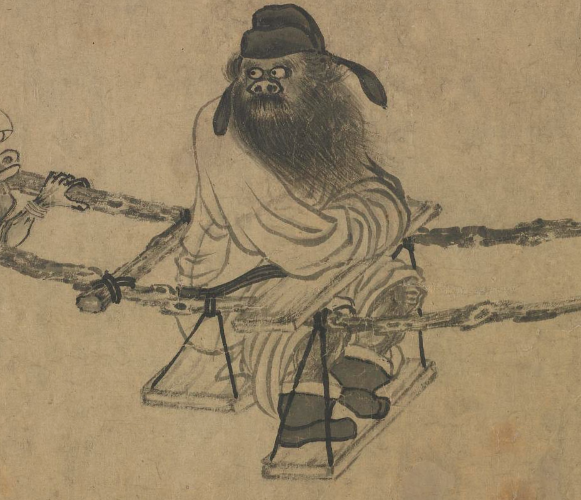

Detail, Zhongshan Going on Excursion, Gong Kai (1222–1307), China, Yuan dynasty, late 13th–early 14th century, Ink on paper, Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1938.4.

Detail, Zhongshan Going on Excursion, Gong Kai (1222–1307), China, Yuan dynasty, late 13th–early 14th century, Ink on paper, Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, F1938.4.

The tradition of Zhong Kui is particularly important as we celebrate this Lunar Chinese New Year which falls on February 12, 2021. With the COVID-19 virus relentlessly killing and sickening people all over the world, we need Zhong Kui, the Demon Queller more than any other time to protect us and provide hope that this pandemic will end soon.

To see more images of Zhong Kui, please visit the Freer and Sackler website.

Further reading from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives collections:

Guo li gu gong bo wu yuan 國立故宮博物院. Ying sui ji fu: yuan cang Zhong Kui ming hu ate zhan 迎歲集福:院藏鐘馗名畫特展. Taibei: Guo li gu gong bo wu yuan, 1997.

Hu, Wanchuan 胡萬川. Zhong Kui shen hua yu xiao shuo zhi yan jiu 鐘馗神話與小說之研究. Taibei: Wen shi zhe chu ban she, 1980.

Lee, Sherman, “Yuan Hui, Zhong Kui, Demons and the New Year,” Artibus Asiae 53, no. 1/2, 1993, pp. 211-227.

Tsai, Chun-Yi Joyce. “Imagining the supernatural grotesque: paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties”. Accessed Jan. 28, 2021. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8RR1X2W

The Garden: A Place to Learn and Experiment

A garden is a place to rest, relax, rejuvenate. It also provides an opportunity to learn about nature. Staff at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives are also learning and developing new skills. Some of these new skills are related to digitization and accessibility of biodiversity literature.

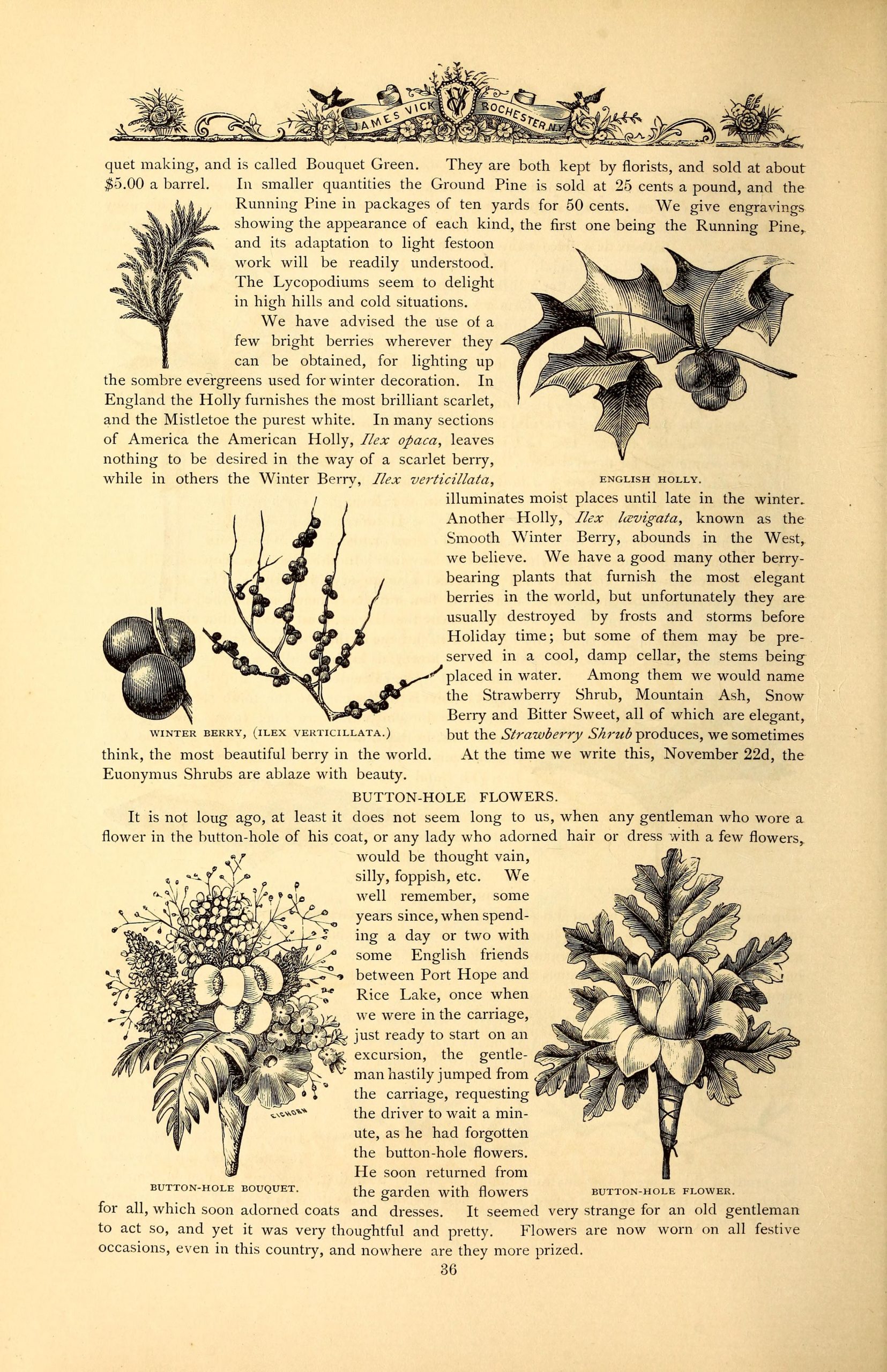

During these months of telework, I am assisting the Digital Library and Digitization Department to enhance page-level and image-level access to previously digitized books for the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). This involves improving page-level metadata for items in BHL, uploading full-page illustrations to the BHL Flickr photostream, and tagging the images in Flickr with species’ common and scientific names. These digitized books include a variety of content: plants, birds, mammals, reptiles, crustaceans, insects, and so much more. In the course of this work, I have the opportunity to view lovely illustrations. Recently a horticultural catalog caught my attention. The item is titled Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878) by James Vick.

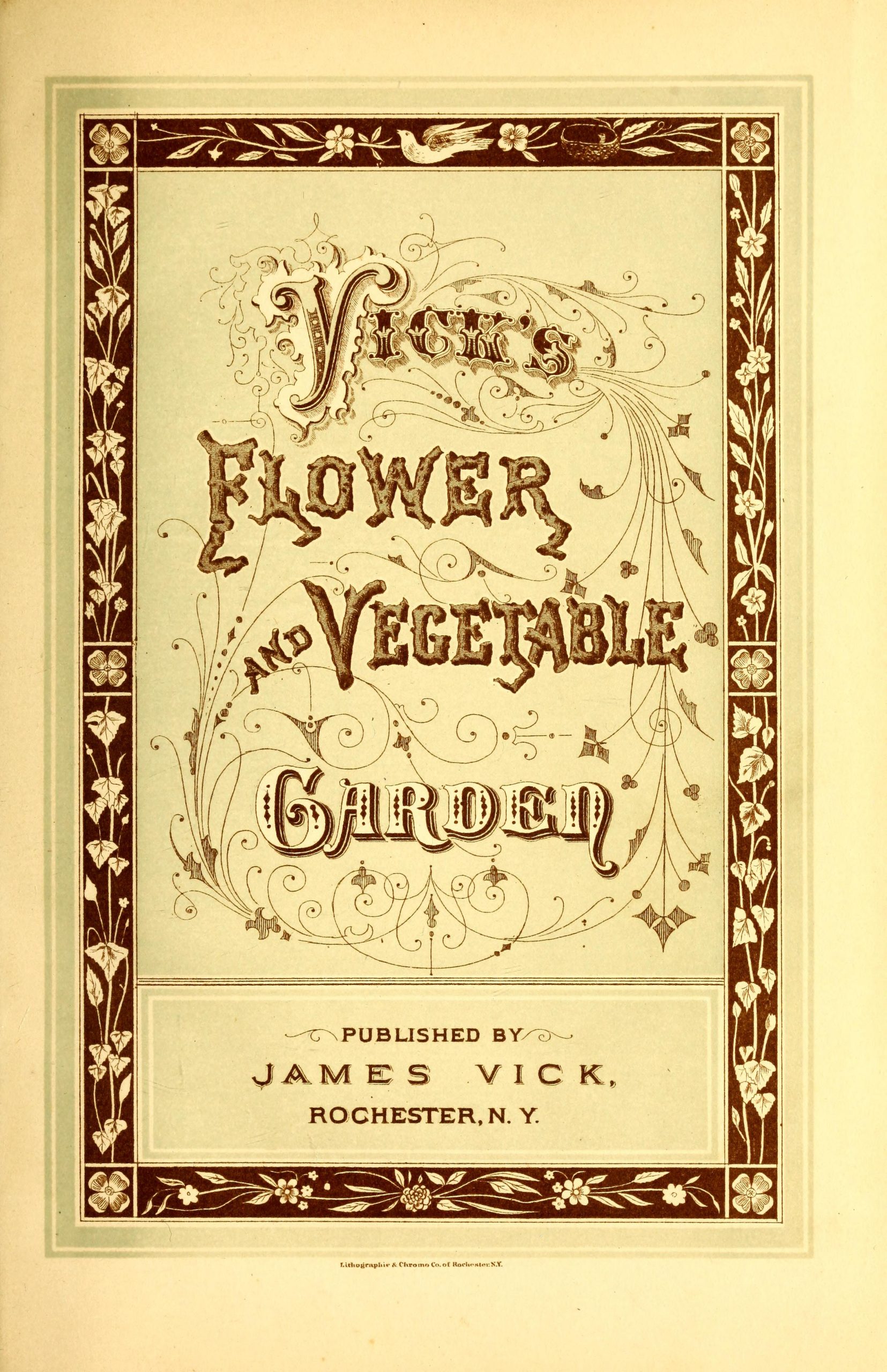

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), title page. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), title page. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick was born in England and arrived in New York City at a young age. There, he learned the printer’s trade. He later moved to Rochester, New York. In Rochester, he set type for several newspapers and went on to serve as writer, editor, owner, or publisher of various publications. In 1862, he issued the first Floral Guide and Catalogue. Based on his past experience in the print and journalism fields, he created a personal style offering gardening advice, anecdotes, correspondence, a complaint section, a children’s section, and color prints. James Vick also began a seed store which later became a well-known seed-display garden. After his death, the company continued into the 20th Century until it was sold to Burpee Seed Co.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 99, Perennials including (1) Aquilegia, (2) Perennial Pea, (3) Digitalis (Fox Glove), (4) Double Pink, (5) Perennial Larkspur, (6) Campanula (Canterbury Bell), (7) Sweet William, (8) Picotee, (9) Pentstemon. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 99, Perennials including (1) Aquilegia, (2) Perennial Pea, (3) Digitalis (Fox Glove), (4) Double Pink, (5) Perennial Larkspur, (6) Campanula (Canterbury Bell), (7) Sweet William, (8) Picotee, (9) Pentstemon. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

This particular item, Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878) by James Vick, is filled with gardening advice, botanical descriptions, and many illustrations. It seems to speak directly to the reader with a conversational tone and focus on learning. As it states on page 5,

“The study of Agriculture and Horticulture has engaged the attention of the wisest from the earliest ages, and yet what wonderful discoveries and improvements have we witnessed in our own day; and we are still learners.”

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 109, Tender Bulbs including (1) Tritoma uvaria, (2) Gladioli, (3) Tuberose, (4) Dahlia, (5) Tigridia. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 109, Tender Bulbs including (1) Tritoma uvaria, (2) Gladioli, (3) Tuberose, (4) Dahlia, (5) Tigridia. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

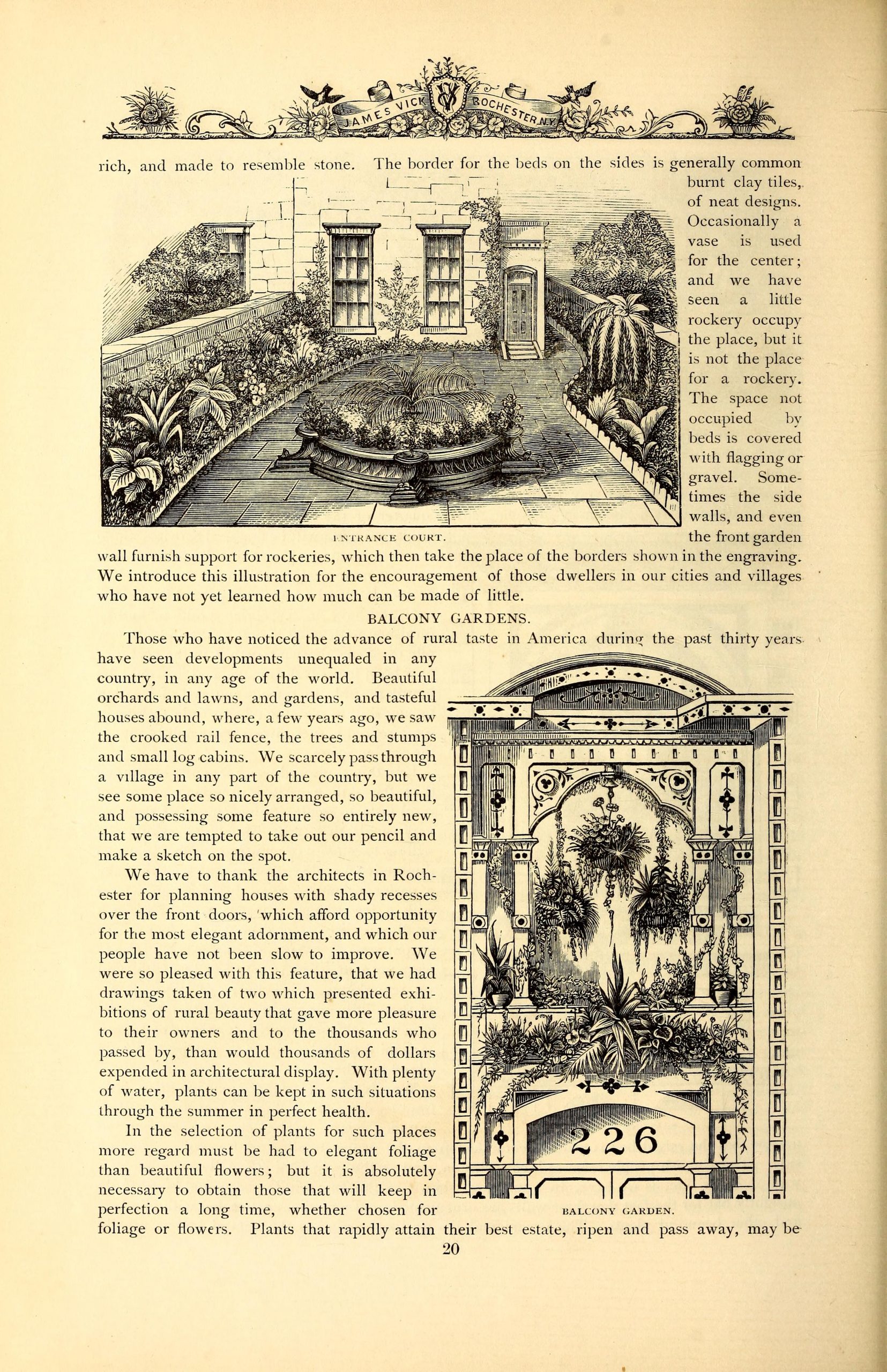

The catalog includes practical suggestions for selecting seeds, preparing soil, and planting gardens. On the subject of garden design, it suggests keeping the future in mind. When planting trees, it emphasizes the awareness of knowing the size, form, and habits of the full-grown tree as opposed to only thinking of its small size when planted. For those with little outdoor space, there are ideas for creating balcony gardens and window boxes.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 20, Entrance Court and Balcony Garden. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 20, Entrance Court and Balcony Garden. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

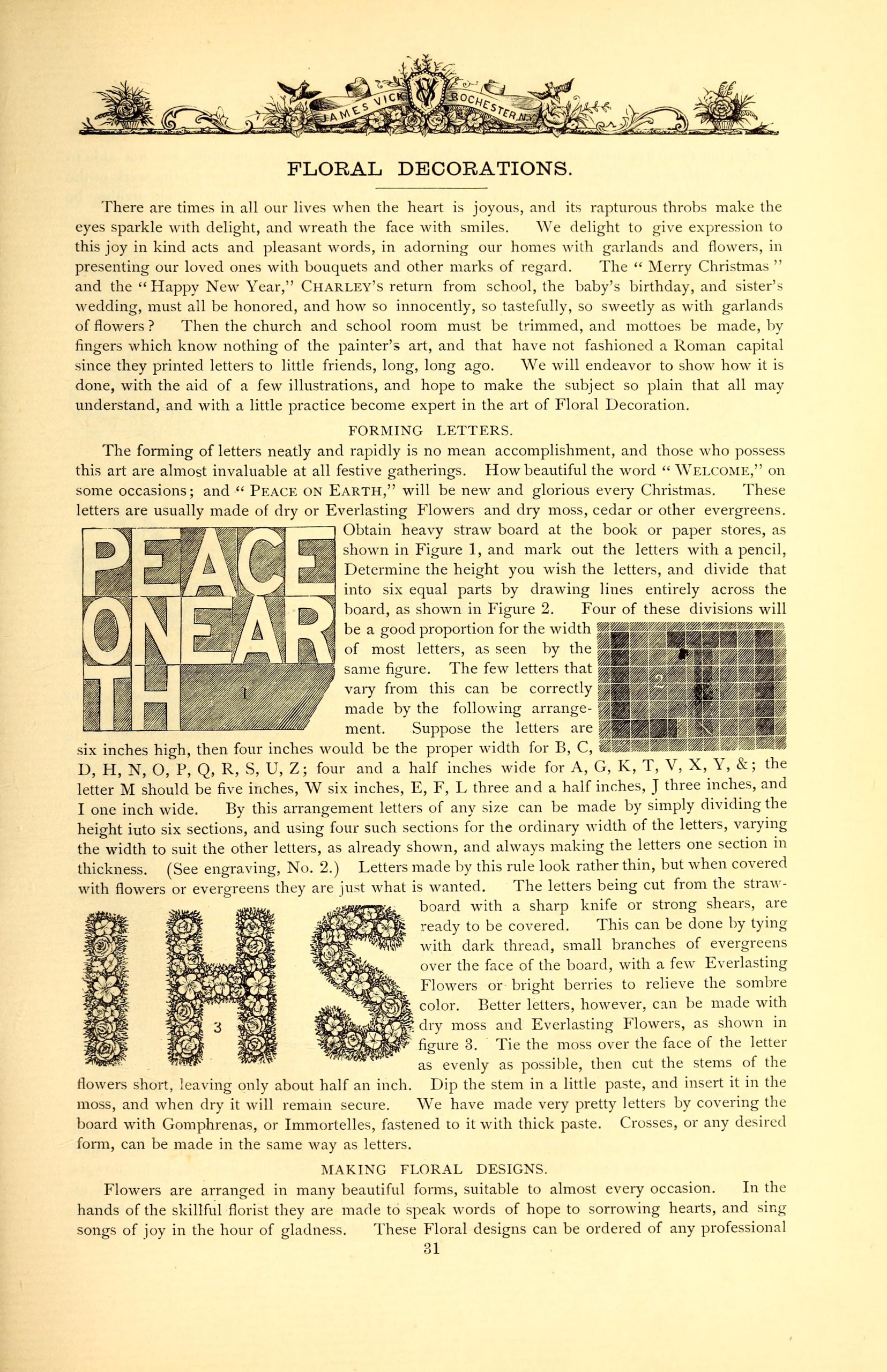

Another section focuses on floral decorations, such as incorporating greenery and flowers into decorations. This might include covering letters with greenery to form welcoming words for a guest, adorning a table with a floral centerpiece, decorating a room with garlands, or creating bouquets and button-hole flowers.

Let’s take a closer look at one of these floral decorations, forming and covering letters with greenery and flowers. Perhaps, someone wanted to welcome a guest by displaying a “Welcome” sign or, as in the example below, decorate the words, “Peace on Earth.” As the catalog explains, the first step was to determine the height of all letters. Then, the width of each letter was determined proportional to its height. For example, if six inches was chosen for the height of all upper-case letters, the proportional width for “P” would be four inches, “E” three and a half inches, “A” four and a half inches, and so on, as detailed in the explanation shown in the image below. Once the letters were outlined on heavy straw board, each letter was cut out and dark thread was used to fasten small branches of evergreens or dry moss to the letters. Finally as a finishing touch, berries or everlasting flowers were added to brighten the decoration, as detailed below.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 31, Forming Letters for Floral Decorations. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 31, Forming Letters for Floral Decorations. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Another floral decoration is the button-hole flower or bouquet. The button-hole flower was simply that, a single flower with a “pretty, sweet-scented leaf” positioned behind it. Thread or string was used to attach the two together (below, bottom right), and then it was inserted into the bouquet holder which was already filled with water. To fasten the button-hole flower to clothing or hair, a pin was attached to the bouquet holder.

On the other hand, the button-hole bouquet was composed of “a few very fine flowers” (below, bottom left). Once the flowers were nicely arranged, the stems were covered with damp moss or cotton and then tinfoil. The button-hole bouquet was inserted into the bouquet holder or attached directly to clothing with a pin.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 36, English Holly, Winter Berry (Ilex verticillata), Button-hole Bouquet, and Button-hole Flower. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page 36, English Holly, Winter Berry (Ilex verticillata), Button-hole Bouquet, and Button-hole Flower. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Almost every page of Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878) includes an illustration. With its conversational style and focus on learning, it encourages readers to try their hand at something new. This might be designing their own garden, planting a small garden in a window box, placing vases or ornamentation around the garden, or creating a floral decoration for a party. For reference purposes, it includes a handy “Botanical Glossary” and guide to “Pronouncing Vocabulary of Botanical Names.”

Towards the end, there are many pages illustrating and describing specific plants. A page focusing on “Classification and Names of Flowers” assists with understanding the divisions of plants as described in this catalog. These divisions include Annuals, Perennials, Greenhouse, Bulbs and Plants, and Holland Bulbs. There is also a section devoted to Vegetables. Detailed information for specific plants includes such things as descriptions, origin, and tips for planting. Every so often, the reader might stumble across a full-page illustration, like the Annuals shown below. Perhaps an illustration such as this might have inspired a bouquet or floral decoration to brighten a room for a holiday or special occasion.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 55, Annuals including (1) Ten-Weeks Stock, (2) Phlox drummondii, (3) Double Portulaca, (4) Balsam, (5) Nemophila, (6) Japan Cockscomb, (7) Pansy, (8) Striped Petunia. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

James Vick, Rochester, NY. Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878), page preceding page 55, Annuals including (1) Ten-Weeks Stock, (2) Phlox drummondii, (3) Double Portulaca, (4) Balsam, (5) Nemophila, (6) Japan Cockscomb, (7) Pansy, (8) Striped Petunia. Available online in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Vick’s Flower and Vegetable Garden (1878) by James Vick is located in the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History. A digitized version is available on the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) and a Flickr album of its full-page illustrations is available on the BHL Flickr. For more information about James Vick, take a look at this BHL Blog post.

Other seed catalogs by James Vick’s Sons are located in a horticultural collection within the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. For more information on one of these catalogs, take a look at this post about Vick’s Garden and Floral Guide (1898) by James Vick’s Sons.

Reference:

“Vick, James.” Biographies of American Seedsmen & Nurserymen, compiled by Marca L. Woodhams, Librarian, Horticulture Branch Library, Smithsonian Institution Libraries, December 1999. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.sil.si.edu/SILPublications/seeds/bios.html#Vick,%20James

Color Our Collections for 2021

Calling all coloring enthusiasts! #ColorOurCollections is back for 2021 and we have a brand new coloring packet just for you. We’ve teamed up with our colleagues at Smithsonian Institution Archives to bring you ten coloring pages to help break your winter boredom. Download them now!

During Color Our Collections, organized by the New York Academy of Medicine, cultural institutions from around the world provide inspiration and free coloring sheets for artists of all ages. At-home artists can share their creations on social media by tagging the organization and using the hashtag #ColorOurCollections. Our coloring book uses images that are freely available in our Digital Library, Biodiversity Heritage Library and Smithsonian Institution Archives Collections.

Cover of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives #ColorOurCollections 2021Coloring Book. Download the full booklet.

Cover of Smithsonian Libraries and Archives #ColorOurCollections 2021Coloring Book. Download the full booklet.

Below, we’ll give you a bit more information about the coloring book images based on books and journals in our library collections. Curious about the Smithsonian Institution Archives images in the packet? Head over to The Bigger Picture blog to learn more!

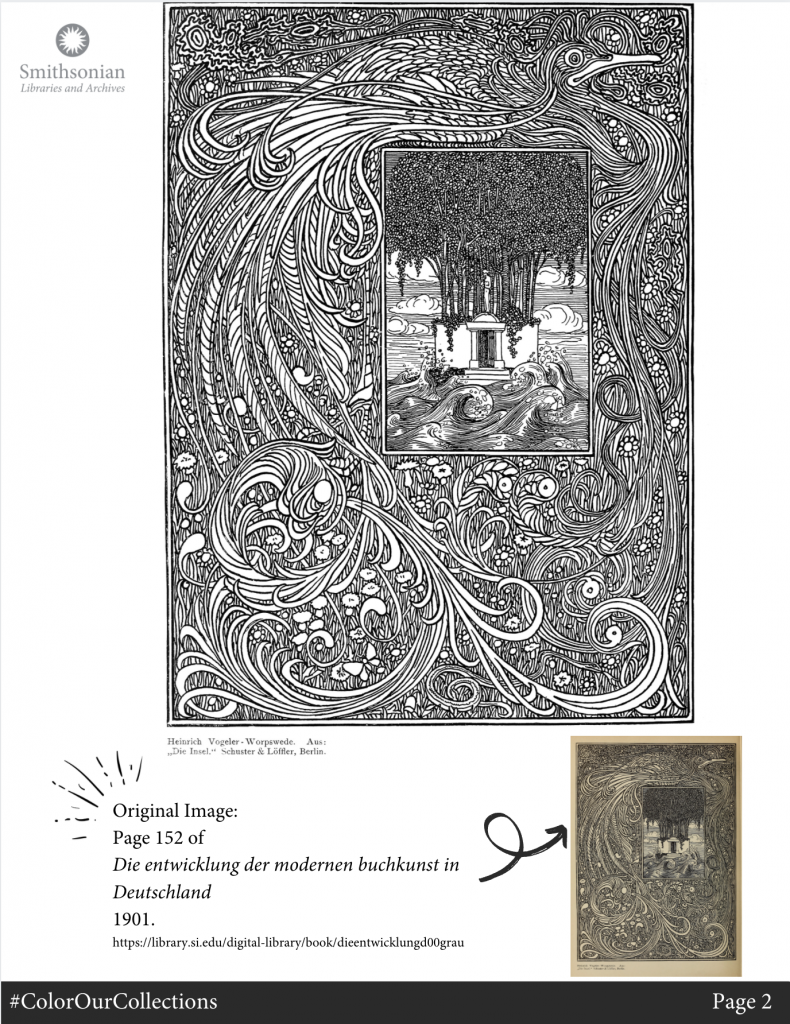

“Die Insel”, Die entwicklung der modernen buchkunst in Deutschland (1901).

Otto Grautoff’s book Die entwicklung der modernen buchkunst in Deutschland (Development of the modern book in Germany) contains page after page of fascinating examples of German book illustration. This elaborate scene by Heinrich Vogeler of “Die Insel” (“The Island”) is no exception. If you’re interested in creating your own coloring pages, or just want to flip through fantastic examples of 19th and early 20th century illustration, Grautoff’s book in our Digital Library is a great starting point.

Coloring page featuring “Die Insel”, in Die entwicklung der modernen buchkunst in Deutschland (1901). Download the full booklet.

Coloring page featuring “Die Insel”, in Die entwicklung der modernen buchkunst in Deutschland (1901). Download the full booklet.

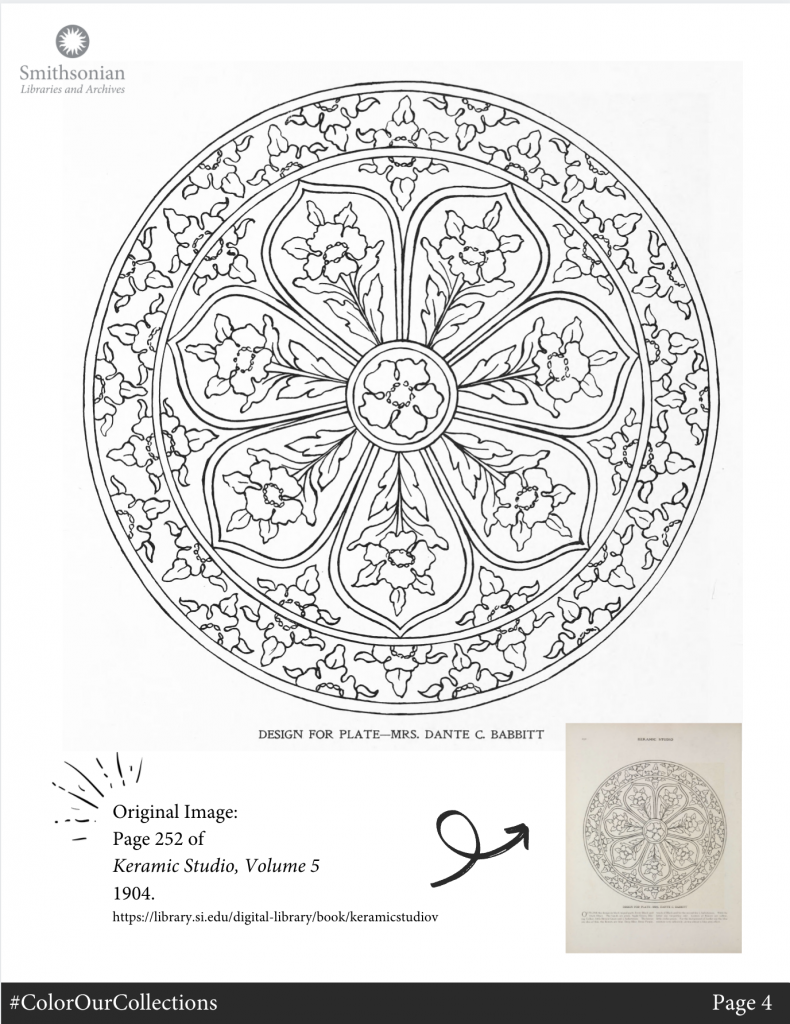

“Design for Plate”, Keramic Studio, Volume 5 (1904).

Mrs. Dante C. Babbitt was one of many talented woman illustrators whose work was highlighted in Keramic Studio, a ceramics design journal started by Adelaide Alsop-Robineau in 1899. The original book page includes instructions for exactly what colors to use when applying this design. But if Apple Green and Deep Blue aren’t part of your preferred palette, feel free to choose your own shades.

Coloring page for “Design for Plate”, Keramic Studio, Volume 5 (1904). Download the full booklet.

Coloring page for “Design for Plate”, Keramic Studio, Volume 5 (1904). Download the full booklet.

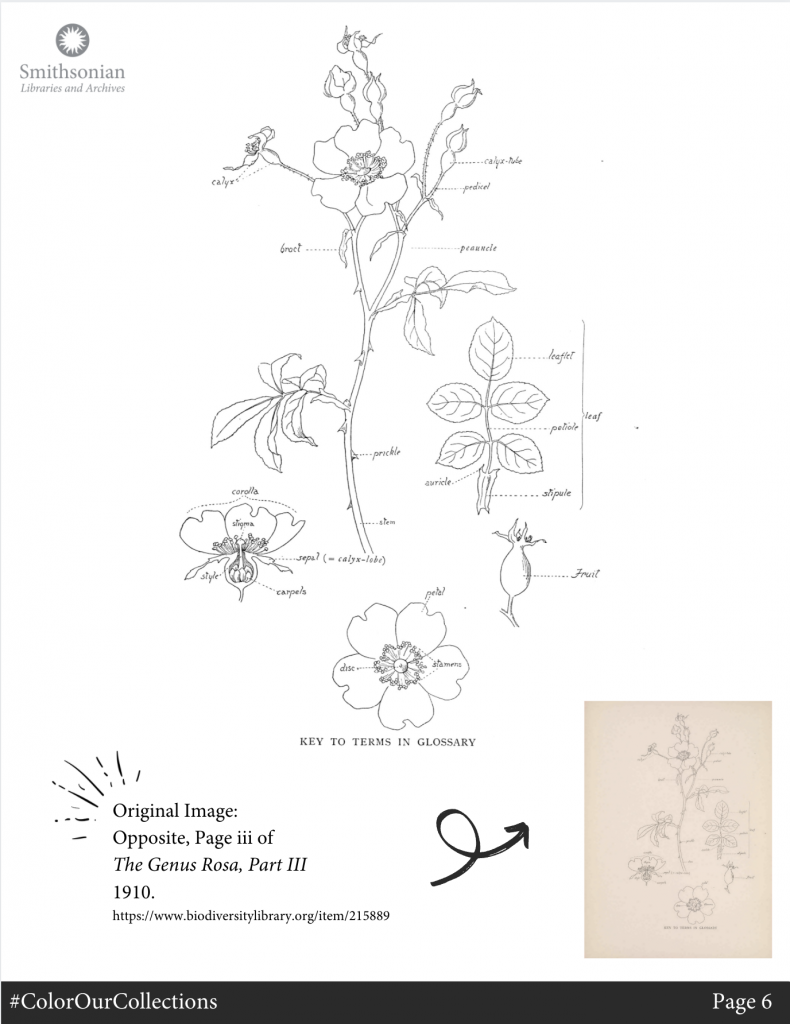

“Key to Terms in Glossary”, The Genus Rosa, Part III , 1910.

With The Genus Rosa (1910-1914), English horticulturalist Ellen Ann Willmott brought together information about known rose species from a multitude of sources. The work was illustrated by Alfred Parsons, a prominent English illustrator, landscape painter and garden designer. Two volumes are available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Coloring page for “Key to Terms in Glossary”, The Genus Rosa, Part III , 1910. Download the full booklet.

Coloring page for “Key to Terms in Glossary”, The Genus Rosa, Part III , 1910. Download the full booklet.

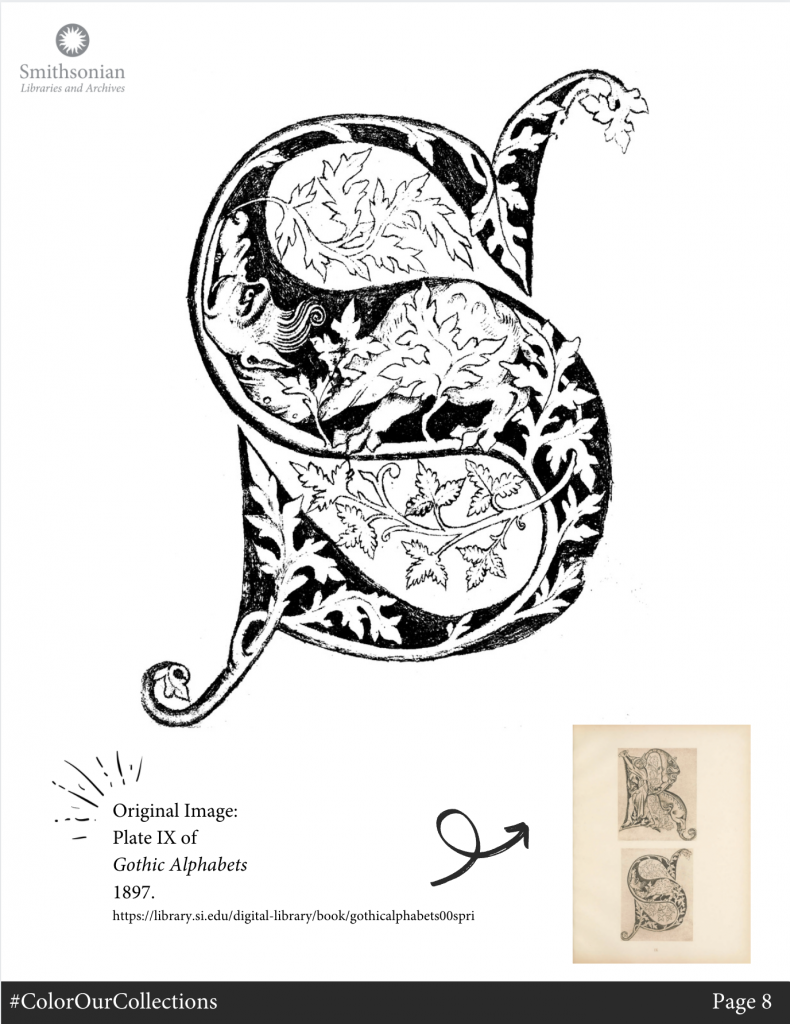

Plate IX, Gothic Alphabets, 1897.

In 2019, Smithsonian Libraries staff members Morgan Aronson and Lilla Vekerdy published Abecedarium: An Adult Coloring Book for Bibliophiles , part history, part coloring book, and part guide to historic books. Where possible, the rare books featured in Abecedarium were digitized cover-to-cover and made available in our Digital Library. Among them, Gothic Alphabets, published in 1897 by International Chalcographical Society with text by Jaro Springer.

Coloring page for Plate IX, Gothic Alphabets, 1897. Download the full booklet.

Coloring page for Plate IX, Gothic Alphabets, 1897. Download the full booklet.

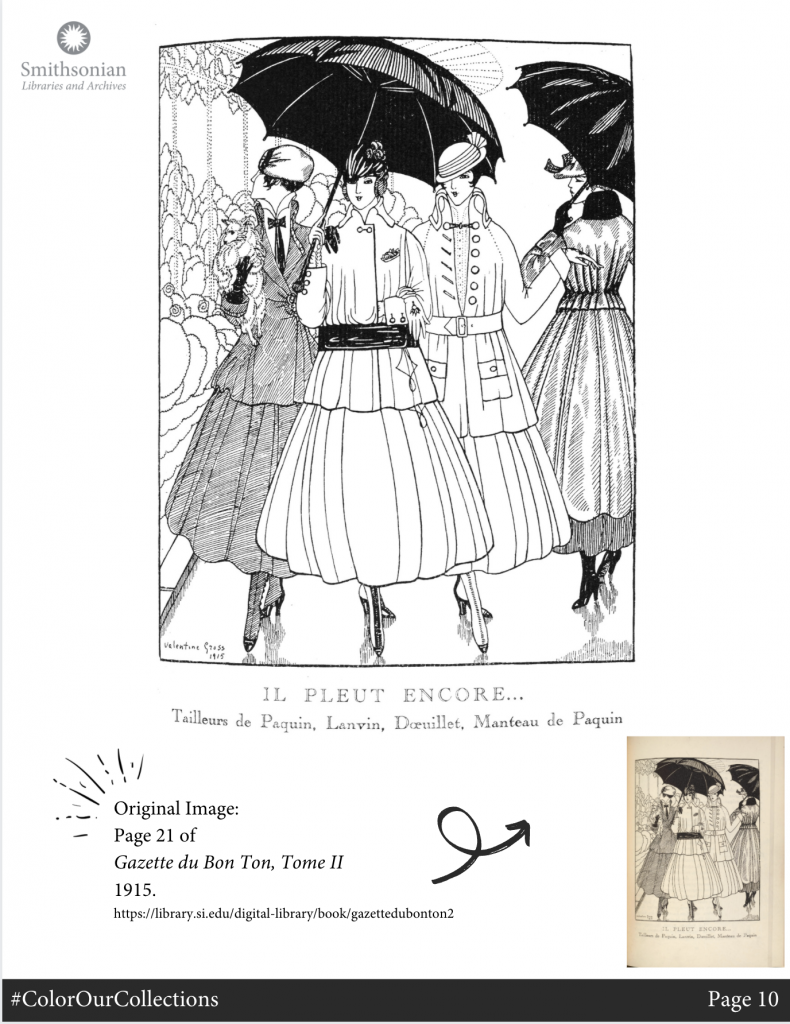

“Il Pleut Encore . . .” Gazette du Bon Ton, Tome II 1915.

Rainwear, but make it fashion. This illustration (“It’s still raining . . .) by artist Valentine Gross Hugo is a wonderful example of how anything could be chic when seen through the lens of French periodical Gazette du Bon Ton. The art and style journal was published by Lucien Vogel between 1913 and 1925.

“Il Pleut Encore . . .” Gazette du Bon Ton, Tome II 1915. Download the full booklet.

“Il Pleut Encore . . .” Gazette du Bon Ton, Tome II 1915. Download the full booklet.

You’ll rarely hear us say this but in this instance it’s true: We hope you enjoy coloring in our books! Share your creations via social media and tag us (@SILibraries on Twitter and Instagram). We can’t wait to see what vibrant combinations you come up with.

Summer 2021 Virtual Internships Available

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives has just opened applications for virtual, paid internships for Summer 2021 through our 50th Anniversary Internship Program. The projects are in a variety of subject areas and are open to both undergraduate and graduate students. Application deadline is March 1, 2021.

Each unique project offers an opportunity to explore current topics in archives, libraries and information science and learn from experienced Smithsonian Libraries and Archives staff in a virtual environment.

Projects include:

- Advancement: delve into online donor engagement and stewardship by assisting with digital marketing and donor relations

- Born Digital Collections: learn how to extract and analyze metadata from born digital holdings and develop and implement a preservation treatment plan for this type of material

- Cataloging: explore bias in current Library of Congress Subject Headings and help make collections description more open, accurate, and inclusive

- Communications: learn how the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives shares its collections and programs with various audiences by evaluating and creating marketing and social media content

- Digital Curation: contribute to the creation of digital resources and exhibitions about the history of Smithsonian women in science by learning how to manage a dataset, developing biographies and researching representation in data

See complete program details and application instructions on our 50th Anniversary Internship page. Learn more about academic appointments and related policies on our Internship and Fellowship page.

Curious about the work of past interns? Read more about their experiences.

Funding for the 50th Anniversary intern class was provided by the Secretary of the Smithsonian and the Smithsonian National Board.

The Prickly Meanings of the Pineapple

The pineapple, indigenous to South America and domesticated and harvested there for centuries, was a late comer to Europe. The fruit followed in its cultivation behind the tomato, corn, potato, and other New World imports. Delicious but challenging and expensive to nurture in chilly climes and irresistible to artists and travelers for its curious structure, the pineapple came to represent many things. For Europeans, it was first a symbol of exoticism, power, and wealth, but it was also an emblem of colonialism, weighted with connections to plantation slavery.

Originating from the region around the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers (present-day Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina), it was an important economic plant in the development of Indigenous civilizations in the Americas. The Tupi-Guarani and Carib peoples called the fruit, a staple crop, nanas (excellent fruit) and several varieties were grown. As well as food, the pineapple was a source of medicine, fermented to become alcohol, its fibers made into robes and bow strings and thread for cloth.

The Aztec word for pineapple is matzatli as seen here is Francisco Hernández’s, Nova Plantarum, Animalium et Mineralium Mexicanorum Historia (1651). The Mayans also cultivated the plant. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by John Carter Brown Library.

The Aztec word for pineapple is matzatli as seen here is Francisco Hernández’s, Nova Plantarum, Animalium et Mineralium Mexicanorum Historia (1651). The Mayans also cultivated the plant. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by John Carter Brown Library.