Libraries' Blog

Handwritten Notes Left Behind from a Steamship Journey

Sometimes, planning a trip is as much fun as the trip itself. The Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library includes catalogs that might have been used to plan vacations. Some are about summer and winter resorts while others describe railway and steamship travel. Let’s take a look at a late 19th Century trip along the Great Lakes.

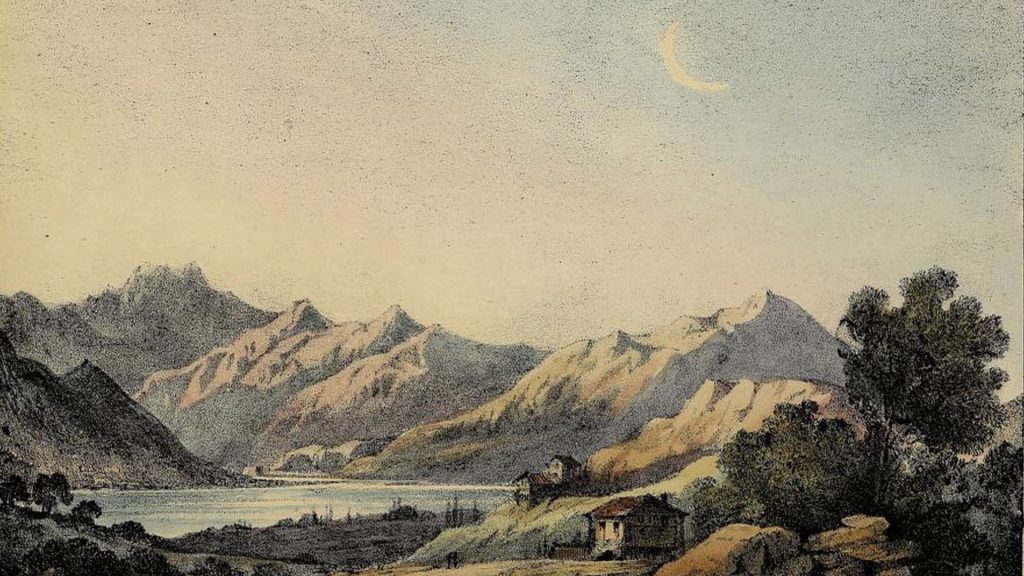

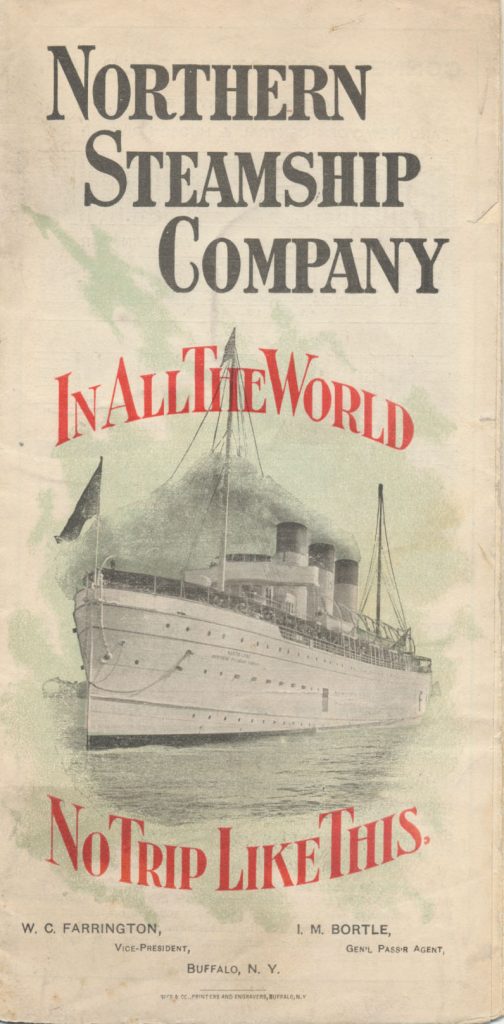

This trade catalog, or small brochure, is titled In All the World No Trip Like This (1898) by Northern Steamship Co. The passengers boarded steamships named “North West” or “North Land” to travel between Buffalo, New York and Duluth, Minnesota. Other destinations in between included Cleveland, Ohio and Detroit, Mackinac Island, and Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan. Railway and steamboat connections were also available in specific cities.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, front cover, steamship.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, front cover, steamship.

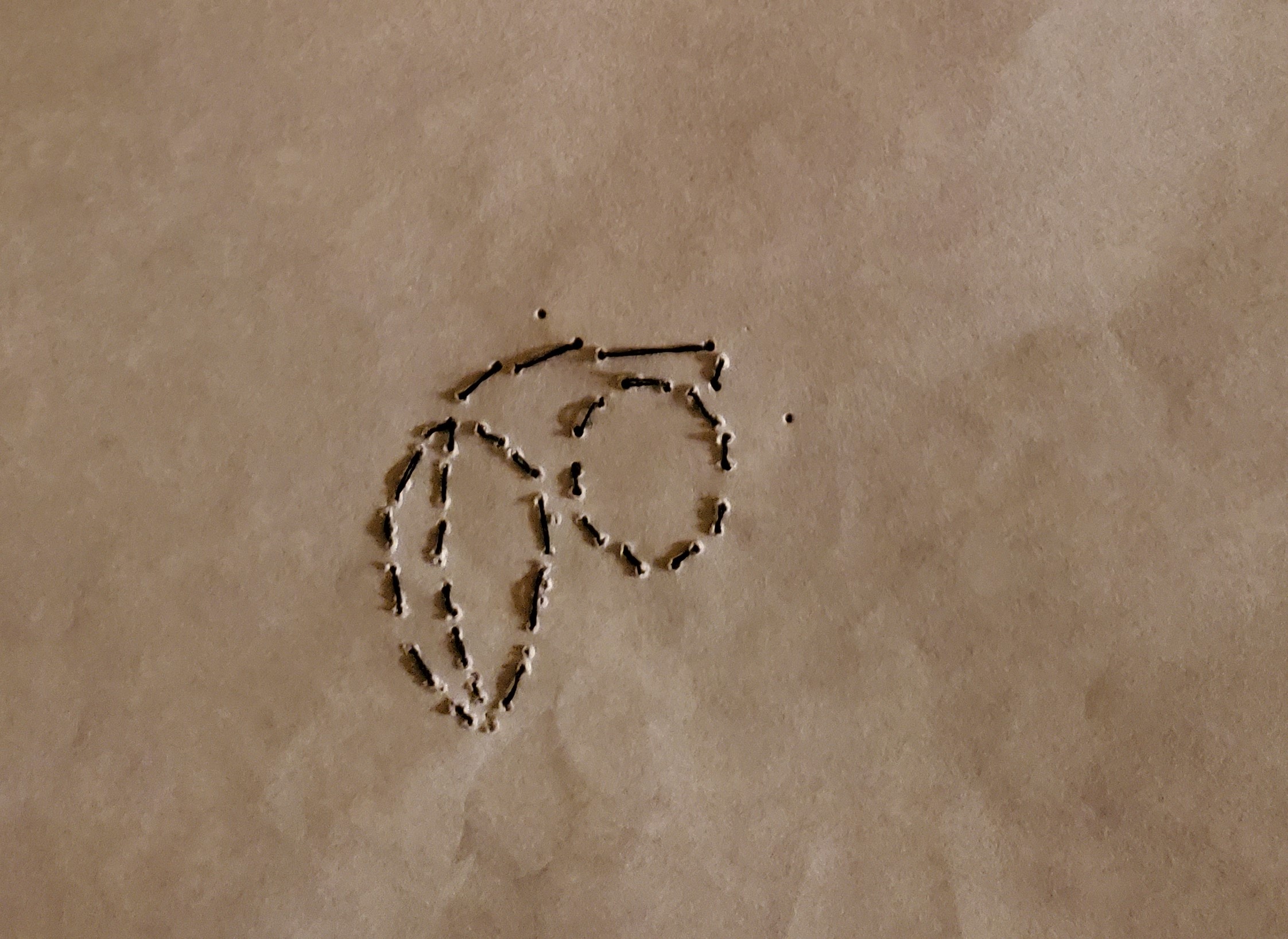

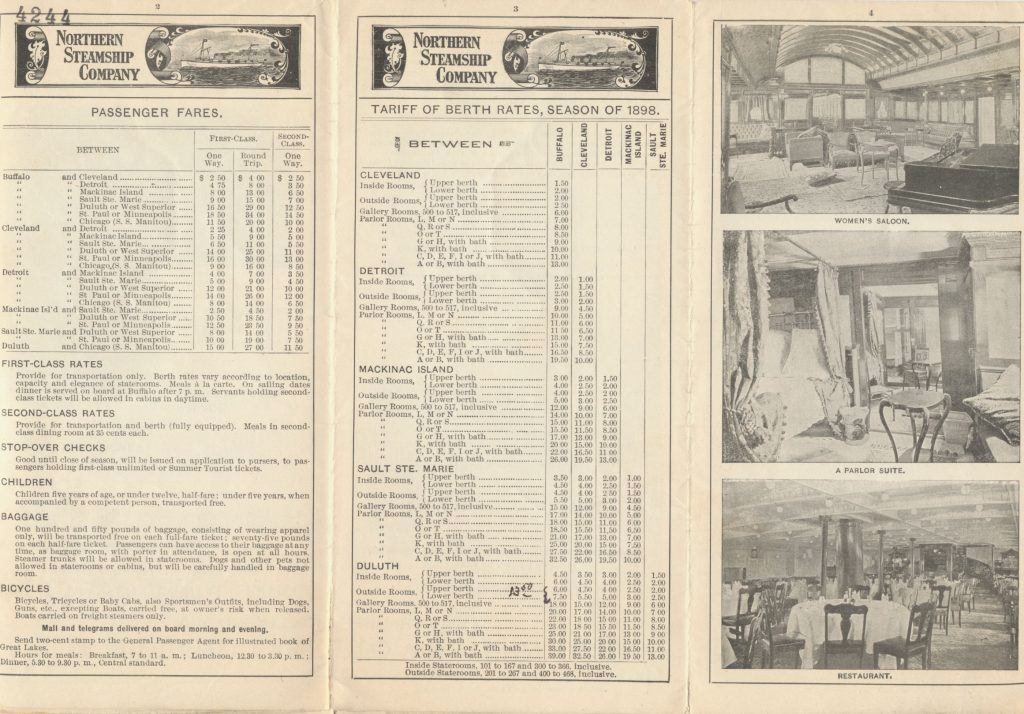

As I opened this brochure, a few handwritten notes caught my eye. Perhaps a travel agent or someone planning a trip in 1898 might have used this brochure. A handwritten note of “13.50” is located by the “Tariff of Berth Rates” for the route between Duluth and Buffalo. The notation, shown below, points to the prices listed for outside rooms: $6.00 for an upper berth and $7.50 for a lower berth.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 2-4, Passenger Fares (page 2), Tariff of Berth Rates for Season of 1898 (page 3), and Women’s Saloon, Parlor Suite, and Restaurant (page 4).

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 2-4, Passenger Fares (page 2), Tariff of Berth Rates for Season of 1898 (page 3), and Women’s Saloon, Parlor Suite, and Restaurant (page 4).

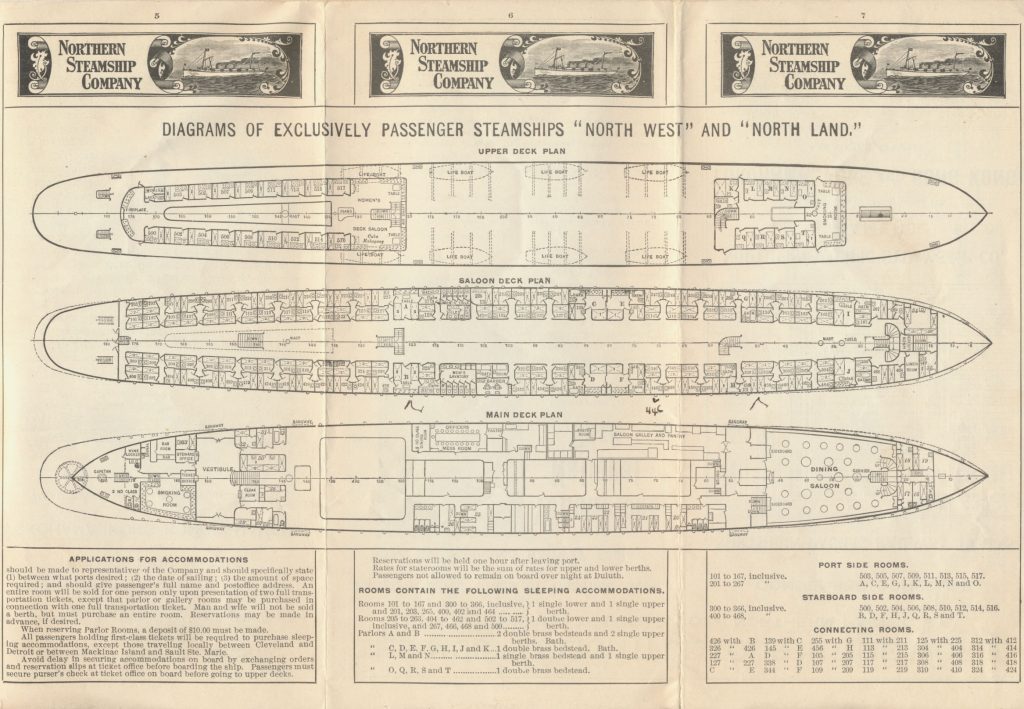

The brochure also includes a detailed diagram of the steamships showing plans for the Main Deck, Saloon Deck, and Upper Deck. A few more handwritten markings, shown below, are found near the plan for the Saloon Deck. In particular, Room 446 on the Saloon Deck is marked. This appears to correspond with the markings above referring to rates for berths. Room 446 was an outside stateroom on the starboard side. It included sleeping accommodations of one double lower berth and one single upper berth.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 5-7, Diagram of plans for Upper Deck, Saloon Deck, and Main Deck for steamships “North West” and “North Land.”

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 5-7, Diagram of plans for Upper Deck, Saloon Deck, and Main Deck for steamships “North West” and “North Land.”

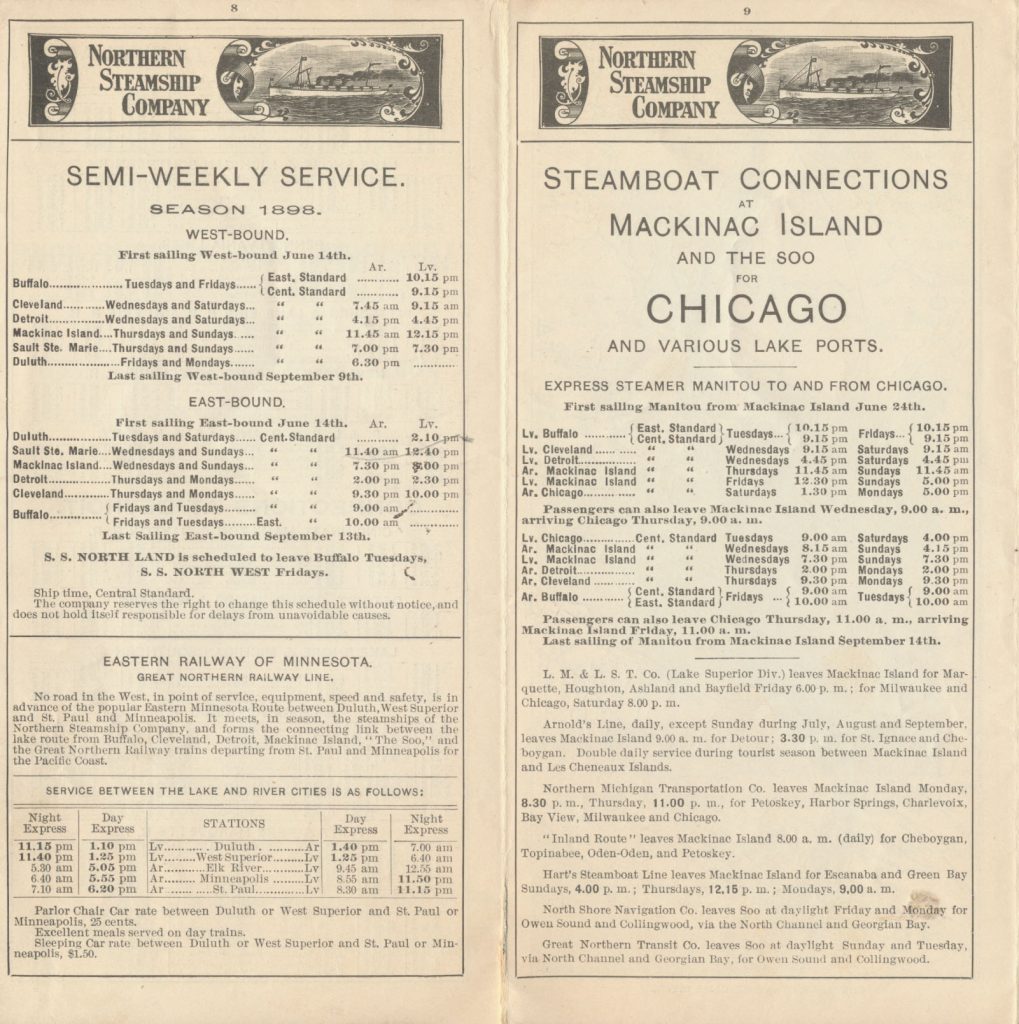

The schedule for the Season of 1898 began on June 14th and ended in mid-September. The journey took approximately three days. According to the “Semi-Weekly Service,” passengers who boarded the “S. S. North Land” in Buffalo, New York on a Tuesday night arrived in Duluth, Minnesota on a Friday evening. A second option was to travel over the weekend, departing Buffalo aboard the “S. S. North West” on Friday night and arriving in Duluth on Monday evening. Stops at cities in between ranged from 30 to 90 minutes while passengers disembarked or boarded. Eastbound steamship journeys were also roughly three days.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 8-9, Semi-Weekly Service for 1898 Season and Service Schedule via Eastern Railway of Minnesota, Great Northern Railway Line (page 8) and steamboat connections to Chicago, Illinois and various lake ports (page 9).

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 8-9, Semi-Weekly Service for 1898 Season and Service Schedule via Eastern Railway of Minnesota, Great Northern Railway Line (page 8) and steamboat connections to Chicago, Illinois and various lake ports (page 9).

The first-class rates provided only transportation. Passengers were required to purchase sleeping accommodations at an additional cost. Second-class rates included both transportation and berth. Those who were local, or day, travelers were not required to purchase sleeping accommodations.

A full-fare ticket allowed 150 pounds of baggage consisting of clothing to be carried aboard for free while half-fare ticket holders were allowed 75 pounds. Baggage was stored in the Baggage Room and accessible at any time. However, steamer trunks were permitted in staterooms and cabins. Pets were not allowed in staterooms or cabins and were cared for in the Baggage Room.

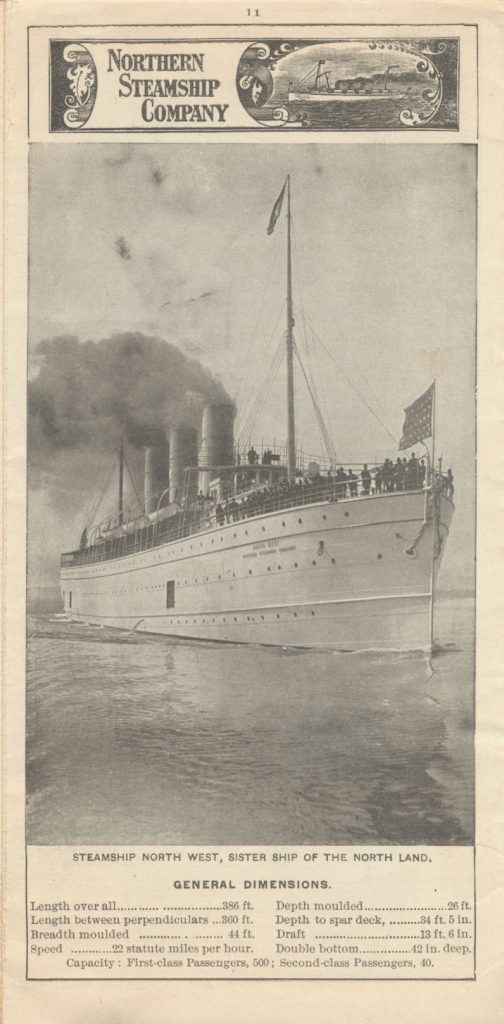

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, page 11, Steamship North West and its dimensions.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, page 11, Steamship North West and its dimensions.

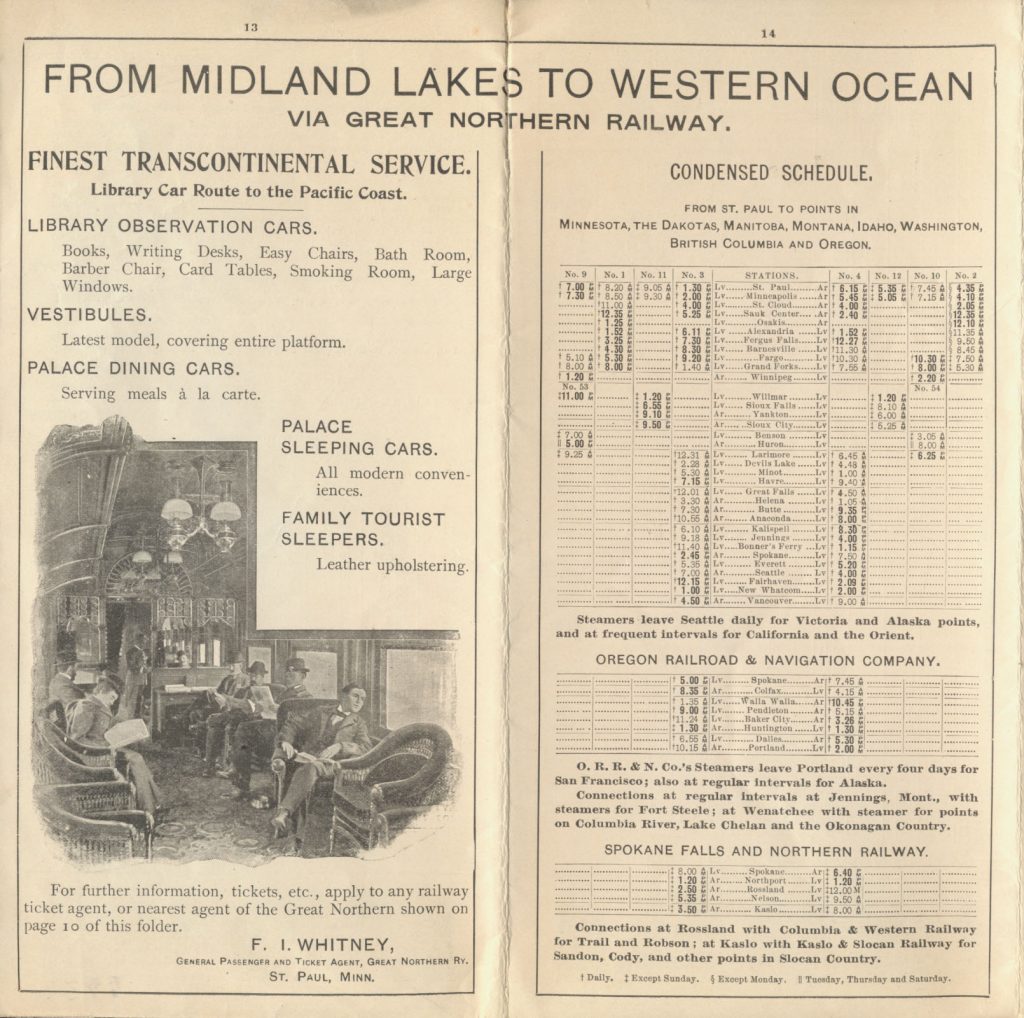

The journey did not necessarily need to end at the dock. Passengers also had the option of connecting to a railroad. For those who extended their trip farther west, they had the possibility of connecting to the Great Northern Railway which serviced points in Minnesota, the Dakotas, Manitoba, Montana, Idaho, Washington, British Columbia, and Oregon. Passengers enjoyed dining and sleeping cars as well as library observation cars. They might have read a book, written a letter, or played cards while watching the scenery go by in one of the library observation cars.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 13-14, Amenities and Schedule for travel via Great Northern Railway from Midland Lakes to Western Ocean and other connections.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 13-14, Amenities and Schedule for travel via Great Northern Railway from Midland Lakes to Western Ocean and other connections.

Another Northern Steamship Co. catalog in the Trade Literature Collection is an illustrated catalog from 1897, one year prior to the brochure described above. This catalog is titled Itinerary: Great Lake Tours (1897). As described on its title page, it is “a compilation of rates and general information of interest to all tourists.”

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, front cover.

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, front cover.

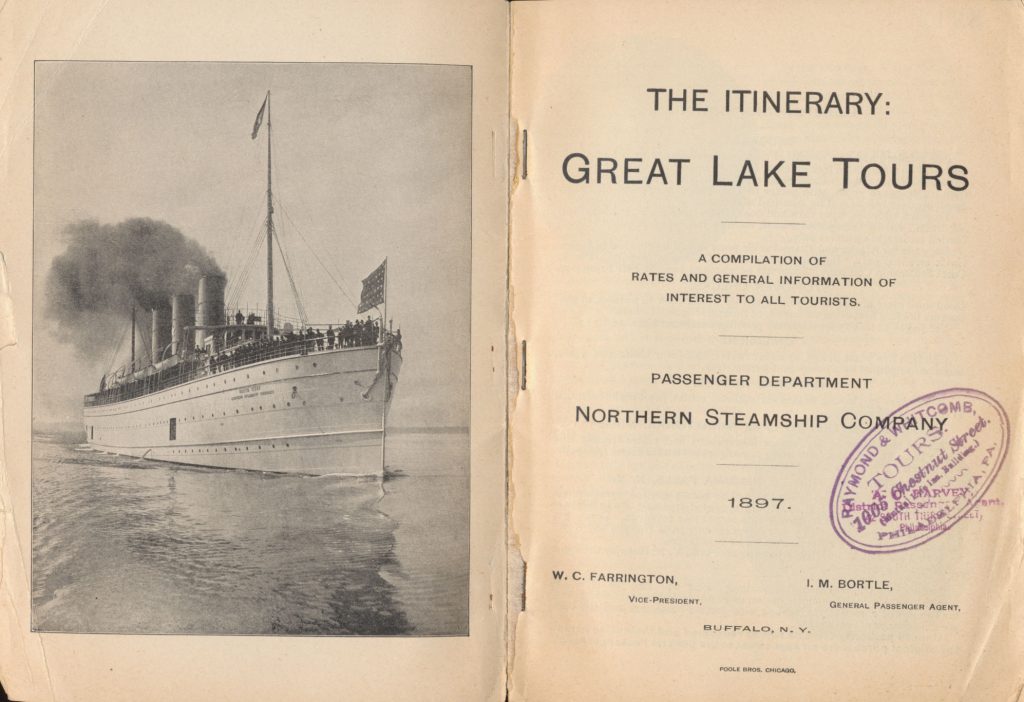

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, title page and preceding page, steamship (shown on page preceding title page).

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, title page and preceding page, steamship (shown on page preceding title page).

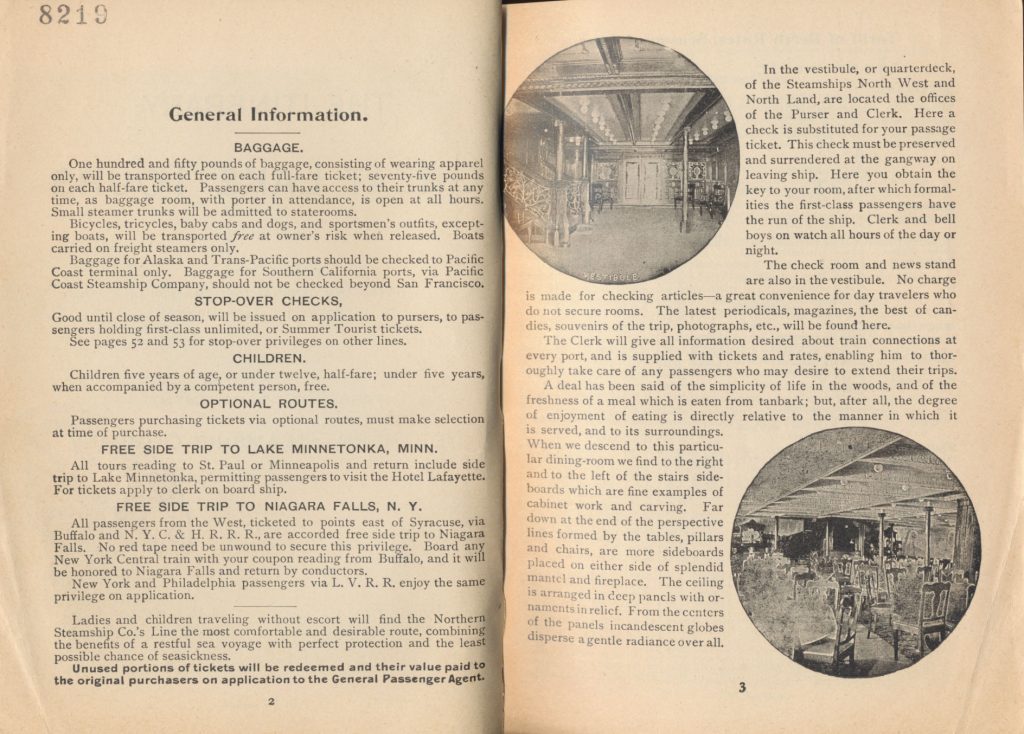

It includes more detail about the procedure to board the steamship. Once on board, passengers proceeded to the Purser and Clerk Offices in the Vestibule. There, they exchanged their passage ticket for a passage check and overnight passengers received their room key. The passage check was later collected as passengers disembarked. Day travelers had the option of checking their items free of charge in the Checkroom. Those interested in a railway connection inquired about the details at the Office of the Clerk. The news stand, also located in the Vestibule, provided souvenirs, reading material, and candy.

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, pages 2-3, general information (page 2) and Vestibule and Dining Room (page 3).

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, pages 2-3, general information (page 2) and Vestibule and Dining Room (page 3).

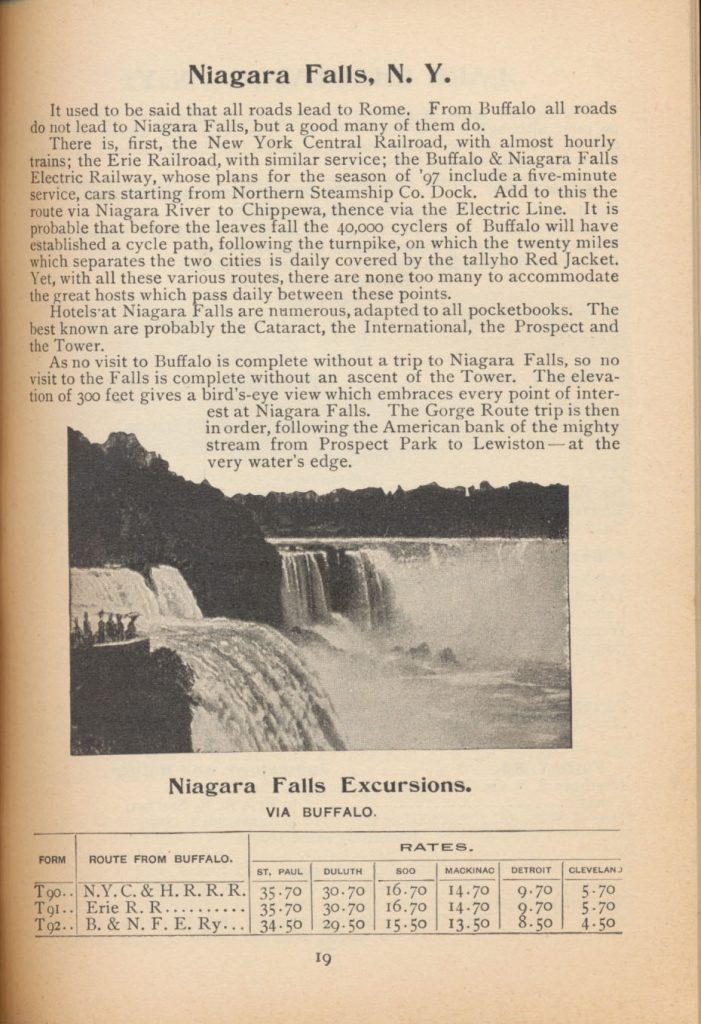

The catalog continues with descriptions of tourist attractions in port cities and nearby excursions. One excursion, described below, took travelers to Niagara Falls, New York. It mentions a few railroads which offered regular service from Buffalo to Niagara Falls.

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, page 19, Excursions to Niagara Falls, New York via Buffalo, New York.

Northern Steamship Co., Passenger Department, Buffalo, NY. Itinerary: Great Lake Tours, 1897, page 19, Excursions to Niagara Falls, New York via Buffalo, New York.

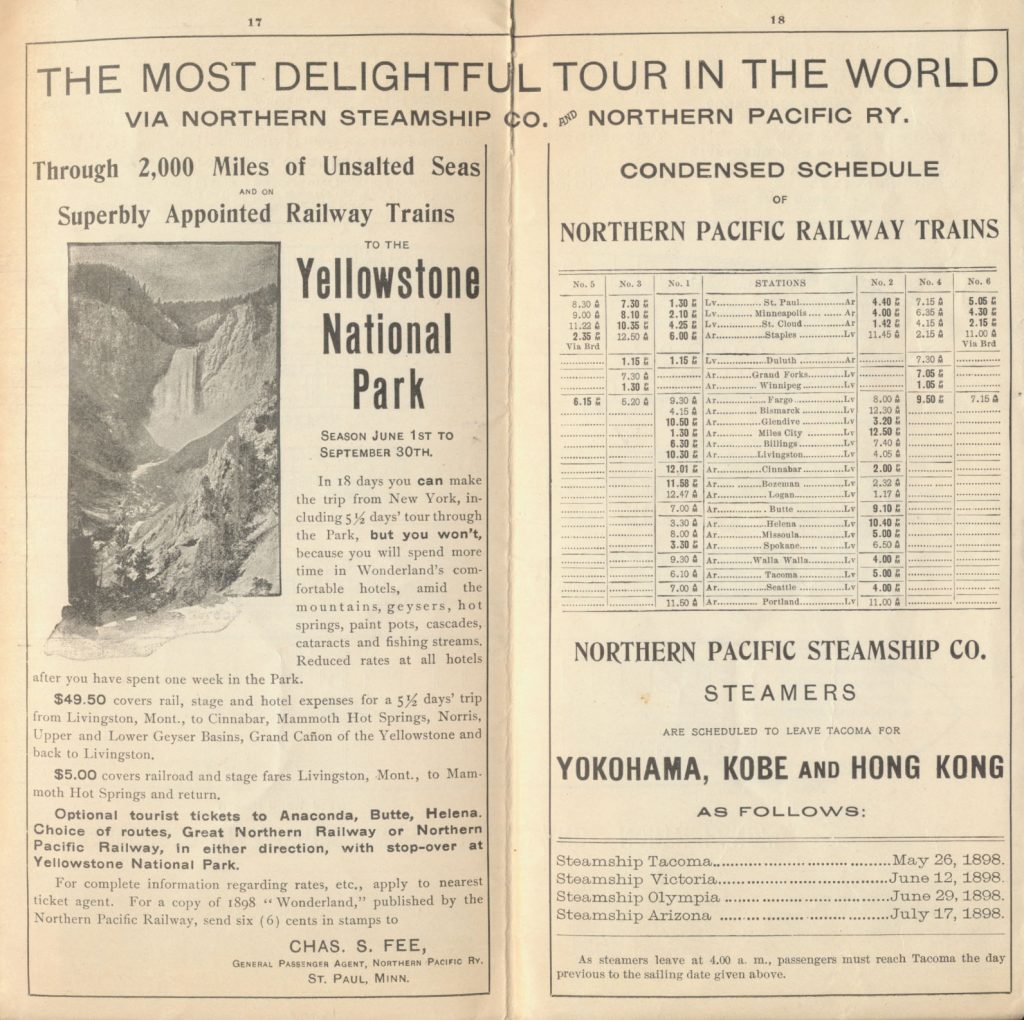

Looking back at the 1898 brochure, In All the World No Trip Like This (1898), it announced an excursion to Yellowstone National Park. Passengers arrived in Duluth, Minnesota via the Northern Steamship Co. and then connected to the Northern Pacific Railway. One travel package was round-trip from Livingston, Montana with rail, stagecoach, and hotel fees for a five and a half day trip to enjoy the sites in Yellowstone National Park.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 17-18, Excursion trips to Yellowstone National Park via Northern Pacific Railway and other connections.

Northern Steamship Co., Buffalo, NY. In All the World No Trip Like This, 1898, pages 17-18, Excursion trips to Yellowstone National Park via Northern Pacific Railway and other connections.

Northern Steamship Co. trade catalogs, including In All the World No Trip Like This (1898) and Itinerary: Great Lake Tours (1897), are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

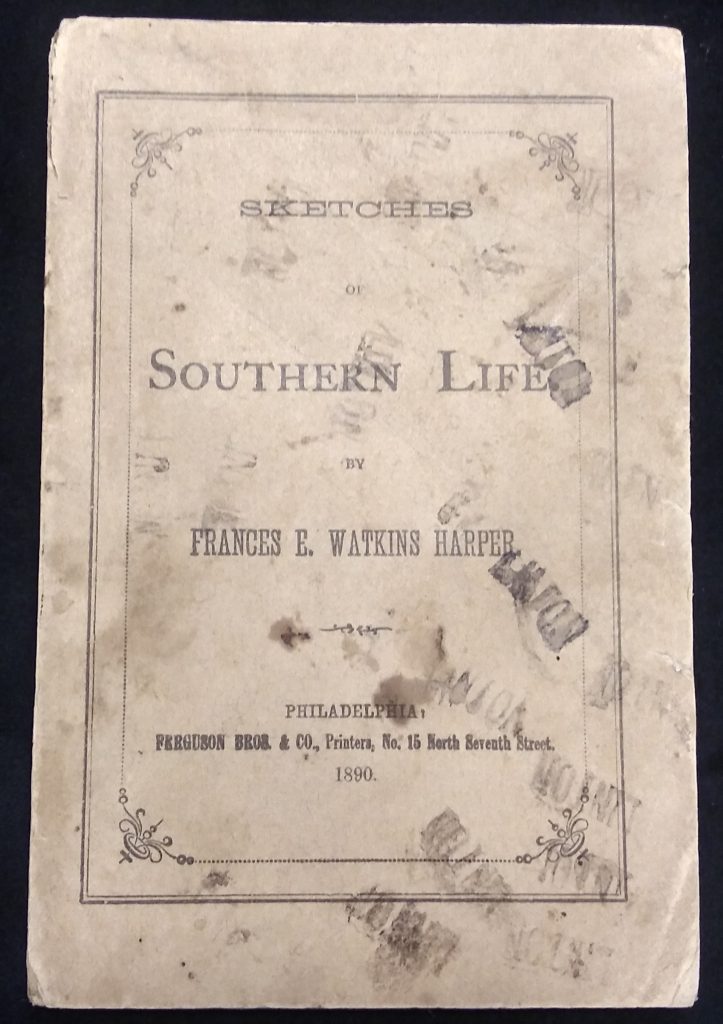

Impactful Work in Education: An Intern’s Experience

This post was written by Cora Nevel, a student at School Without Walls in Washington, DC, who recently interned in the Smithsonian Libraries Education Department.

This past fall semester (2019), I interned with the Smithsonian Libraries Education Department. I had lots of fun those few months, and I learned a lot about Latin America, women’s history, rare books, and the Smithsonian itself. The Smithsonian has more resources than I could possibly imagine, and every week I had something new to read about.

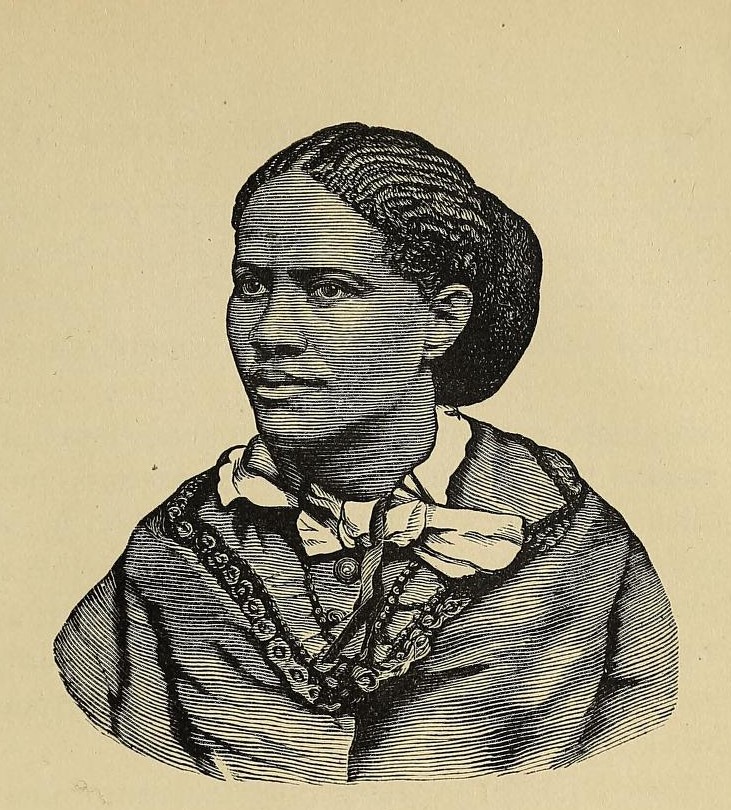

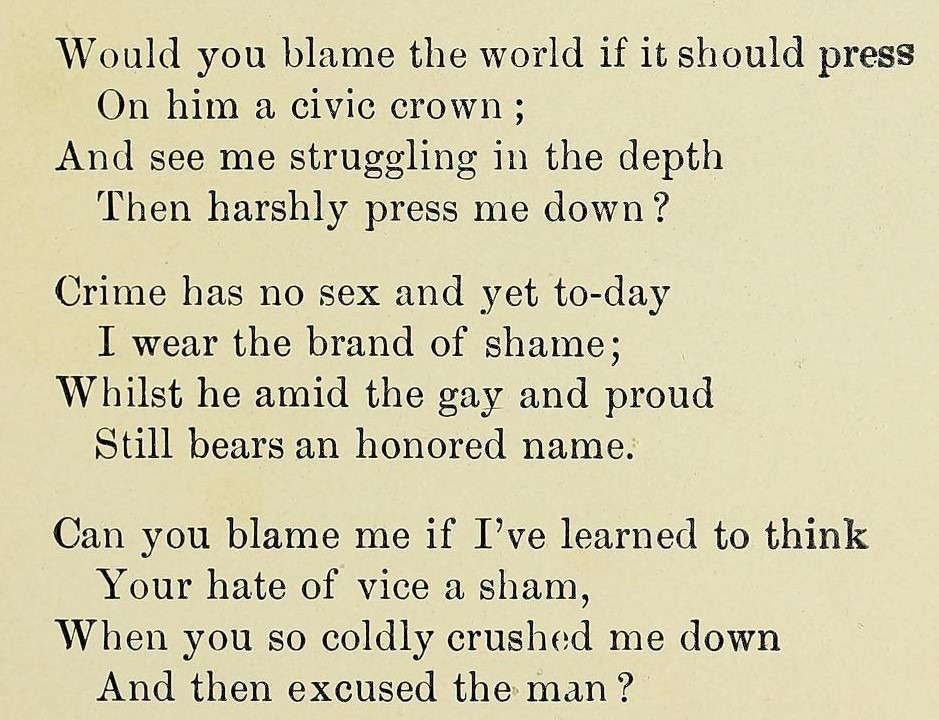

Over the course of the semester, I had a small hand in a lot of different projects. I sorted, counted, proofread, stickered, and come close to bleeding (I’m no longer allowed to use X-acto knives) for our Latinx Traveling Trunks project. Additionally, I playtested (and later, just played) the department’s Wizardry-themed box. But the majority of my time went towards our American Women’s History project. I’ve flipped through biographies, memoirs, pamphlets, poetry, and periodicals full of fascinating women. I loved reading about women I’d never heard of before. The best women to read about were the ones with the most niche contributions.

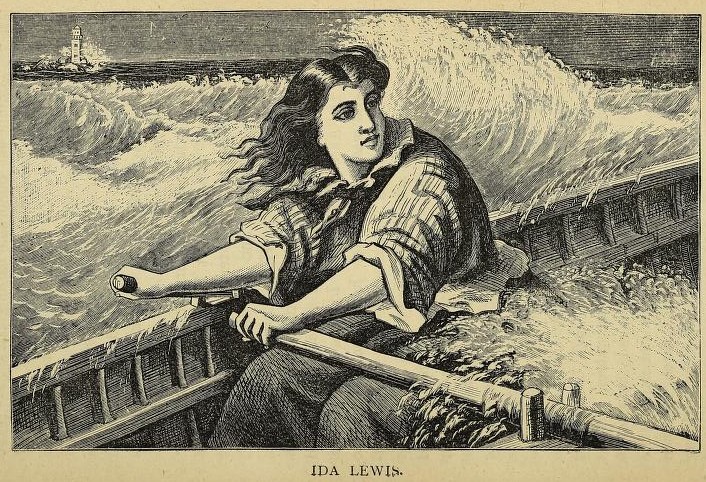

Ida Lewis from Daughters of America

Ida Lewis from Daughters of America

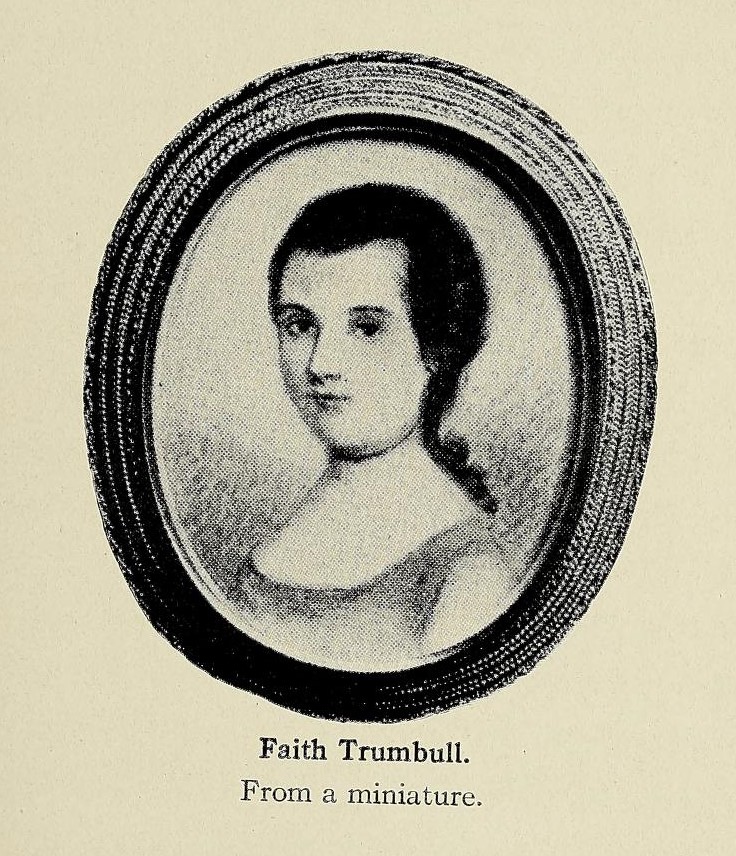

My two absolute favorite women to read about were Ida Lewis and Faith Trumbull. Lewis (pictured above) lived at a lighthouse, and was well known for rescuing many a drowning person over the course of her lifetime. According to what I’ve read, she received all kinds of fan mail, and was even visited by the president for it. Trumbull (pictured below) was mostly known for donating her expensive red cloak to the American cause during the Revolutionary War. Apparently, it was later cut up and used to embellish soldiers’ uniforms. She was important for more than just that, though. Her home was allegedly called the “Lebanon War Office,” since members of the Continental Army and French allies often visited. I also read that her home served as the headquarters for the Connecticut Council of Safety during the war.

Faith Trumbull from The pioneer mothers of America v.3

Faith Trumbull from The pioneer mothers of America v.3

While I certainly enjoyed my time here, the work could get challenging. Sometimes, I was definitely in over my head. I’d never set up a 3D printer before, but that did not stop me from trying. And, thanks to the internet, I would say I was fairly successful.

I learned a lot of new skills, and polished others, although not always ones I expected. I learned how to use a copy machine and a paper shredder, but also how to fill a piñata, make Halloween decorations, set up a 3D printer (not one, but two different kinds), craft the perfect office playlist, and to perfectly time when I leave so I don’t have to wait for the bus. I’ve also gotten to hone my acting and photography skills. Above all, I’ve mastered the art of organization.

Looking back, I am so grateful that I’ve had this experience. I’ve done so many things that I never would have gotten to do, or even thought to do on my own. I’ve also had the pleasure of spending time with a group of interesting people, and getting to be a part of a vast, intricate, and impactful network. All in all, it was a semester well-spent, and I won’t forget it.

Celebrating a Centennial: 100 Years at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library

Three Cheers for 100 Years of Fine Arts research at the Smithsonian!

Floor plan of the U.S. National Museum, now the National Museum of Natural History, noting the alcove in the West Court that was home to the original AA/PG Library.

Floor plan of the U.S. National Museum, now the National Museum of Natural History, noting the alcove in the West Court that was home to the original AA/PG Library.

The largest art library of the Smithsonian Institution hits a major milestone on July 1, 2020: the American Art & Portrait Gallery (AA/PG) Library celebrates its centennial. And in that 100 years, the Library has changed its name more times than its staff would care to admit (ok, we will admit it—six times.) The Smithsonian was founded in 1846 and held a nascent collection of art and art publications. According to an early staff person, “It has always been a matter of sentiment…that the Institution should have an Art Room, and that there should be in this Art Room a collection of books relating to the fine arts.”1 In fact, it was the Smithsonian’s first librarian who cared for the paintings and sculpture, so naturally the Smithsonian collected books on the aesthetic qualities of the fine arts from its earliest days.

But in 1920, Congress allotted resources for the Smithsonian’s department of fine arts to become its own separately funded, distinct museum—the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art, which has an interesting history. At that time, the scattered collection of books on the fine arts were brought together to form the nucleus of the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art Library, as the first fine arts library at the Smithsonian Institution, and of the federal government of the United States.

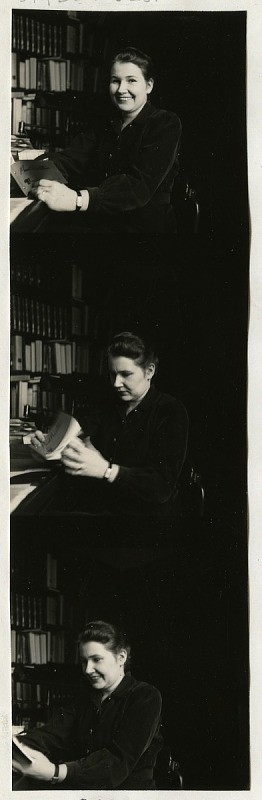

Lucile Torrey Barrett Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts Librarian 1937-1942, photo by RP Tolman. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7433, Box 3, Folder: Scrapbook A-N

Lucile Torrey Barrett Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts Librarian 1937-1942, photo by RP Tolman. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7433, Box 3, Folder: Scrapbook A-N

One hundred years ago, the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art Library was shelved in a tiny alcove in what is now the National Museum of Natural History, barely a few hundred books, with no staff to manage its care and growth. It grew slowly but steadily, supporting exhibitions in the Gallery’s rooms at the Natural History Museum in all periods of international art history. In the 1960s, the library was strengthened when it was re-dedicated to also support the brand new National Portrait Gallery, along with the National Collection of Fine Arts, and the library moved from its small alcove to its own large, beautiful space in the Patent Office Building.

Today, in 2020, the American Art & Portrait Gallery Library spreads across two floors of the Victor Building with its more than 180,000 books and journals, its half a million files of ephemera, and a team of art librarian professionals to see to its continued success. The Library supports the mission of the Archives of American Art, the National Portrait Gallery, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Renwick Gallery through its comprehensive resources in American art and biography. It serves the specialized research needs of the Smithsonian staff and affiliated fellows and interns by building, managing, and preserving the library collection and providing in-depth research services. It also serves non-Smithsonian scholars and the community through its public hours, interlibrary lending and reference services.

The Library staff is proud to support the ongoing success of arts research and scholarship at the Smithsonian. The robust Fellowship Program at the American Art Museum, now in its 50th year, has allowed emerging and established scholars to engage with the Library’s immense research resources, and the fellows who have worked in the AA/PG Library go on to write significant publications with new narratives, curate important exhibitions, and share a love of art by teaching students in art history and the humanities. The Library itself has been host to hundreds of interns, helping the next generation of art information professionals succeed. The AA/PG Library has been an indispensable source for curators, scholars, art enthusiasts and collectors, educators and students in the United States and beyond.

As we look to the future, AA/PG continues to work toward its goal to be the foremost library in the world dedicated to American art and portraiture. To that end, the library will continue to add collections that reflect the depth and breadth of that subject matter, to expand our scope to highlight historically marginalized voices in American history, and to care for, organize and make these resources accessible.

Current AA/PG Reading Room, photo by Matailong Du

Current AA/PG Reading Room, photo by Matailong Du

In 2021, the AA/PG Library will undergo a renovation to its primary area of service, increasing security of collections, refreshing outdated and damaged fixtures, enhancing programming areas, and creating spaces to be more collaborative. The plan will transform the AA/PG Library by enhancing social interaction, cross-disciplinary learning, and propel the look and function of such a prestigious library into the next century. The Art & Artist Files collection, one of the jewels of the AA/PG Library, will have important investment in housing and organization, as it moves from nearly 100–year–old filing cabinets to purpose-built new housing. The Library aims to increase digital and physical findability, making our spectacular materials available to more people all over the world.

As we move into our next century, we need your help to make this growth possible, and to further enhance the quality of American art and historical research! To learn about opportunities for support, please contact the Smithsonian Libraries’ Advancement Office at LibraryGiving@si.edu or 202.633.2241.

AA/PG Library rendering of renovated entrance, planned 2021

AA/PG Library rendering of renovated entrance, planned 2021

Resources Consulted:

1 – Letter from Paul Brockett, Asst Librarian, to W. de C. Ravenel on what to do with the art books in “The Art Room” and a note that the Secretary would have to decide if books held in the Castle could go to the new NGA Library, November 15, 1919. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 311, Box 016 Folder: 5

Annual report of the Smithsonian Institution, U.S. National Museum. Washington :G.P.O.,1907-1951. Consulted years: 1907, 1917, 1924,

“Report on the National Gallery of Art” from Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1921,

Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 311, Box 016 Folder: 5 and Record Unit 463, boxes 1, 2, 4.

Lonely Planet in Edo-period Japan: Meisho Zue

The Edo period (1600-1868) in Japan was a time of prolonged peace. Ruling under an isolationist foreign policy (Sakoku) and with no civil wars, the Tokugawa Shogunate government focused on social and political stability, and securing infrastructure. They created and regulated five major roads, boarding houses and transportation systems in order to strengthen central control over the daimyōs (Sankin kōtai — a governmental policy requiring the daimyō to live in their domain for one year and in Edo the alternate year). Currency circulation was also regulated, which brought economic stability and a flourishing of the commoners’ life. Urban citizens who can afford developed their own leisure activities. This phenomenon was called “chō’nin bunka” (townsmen culture). They enjoyed reading, performing arts, seasonal events and festivals, some of which had been privileges of only samurais and aristocrats earlier.

Beginning with the Kyōho period (1716-1736) traveling became a commoners’ popular pleasure reaching a peak during the Bunka-Bunsei periods (1804-1830). Commoners’ traveling was limited to pilgrimage to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. The most popular destination was the Ise Shrine in present Mie Prefecture which experienced an explosive growth in popularity. Travelers gradually found ways to take advantage of pilgrimage permissions by adding “on-our-way” destinations to the itinerary. Samples of those “on-our-way” destinations were Osaka and Kyoto both relatively close to Ise Shrine. Hence the Edo period saw the beginning of a commoners’ travel boom aided also by the well-maintained highway system mentioned earlier.

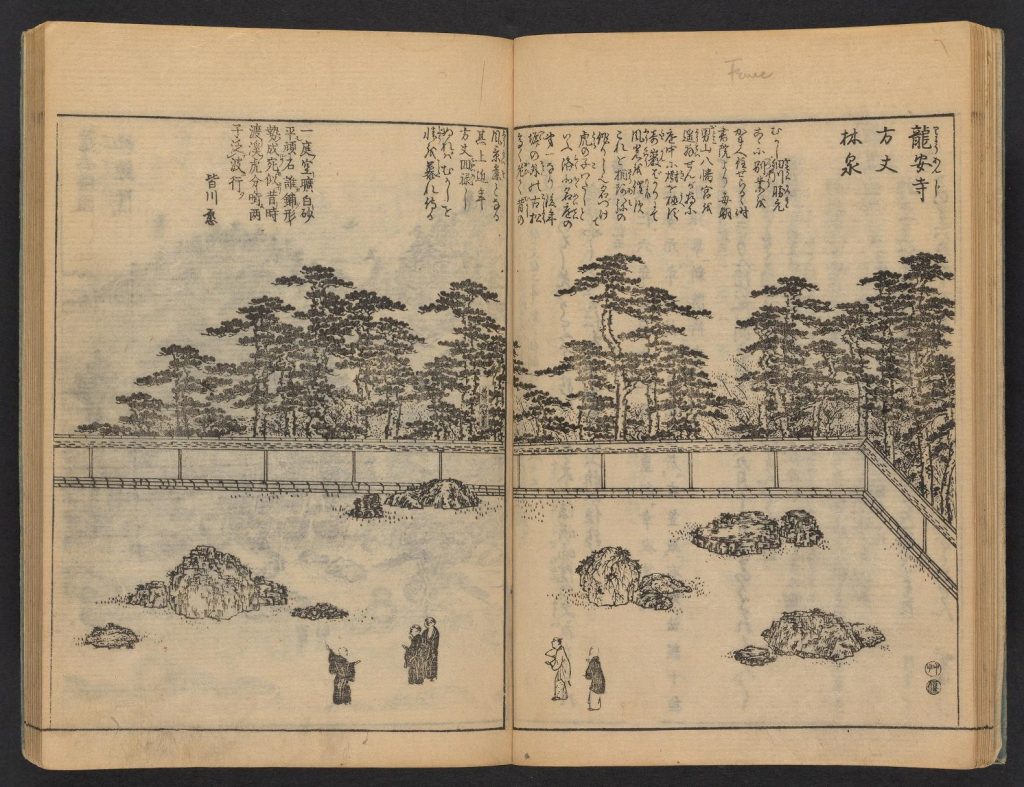

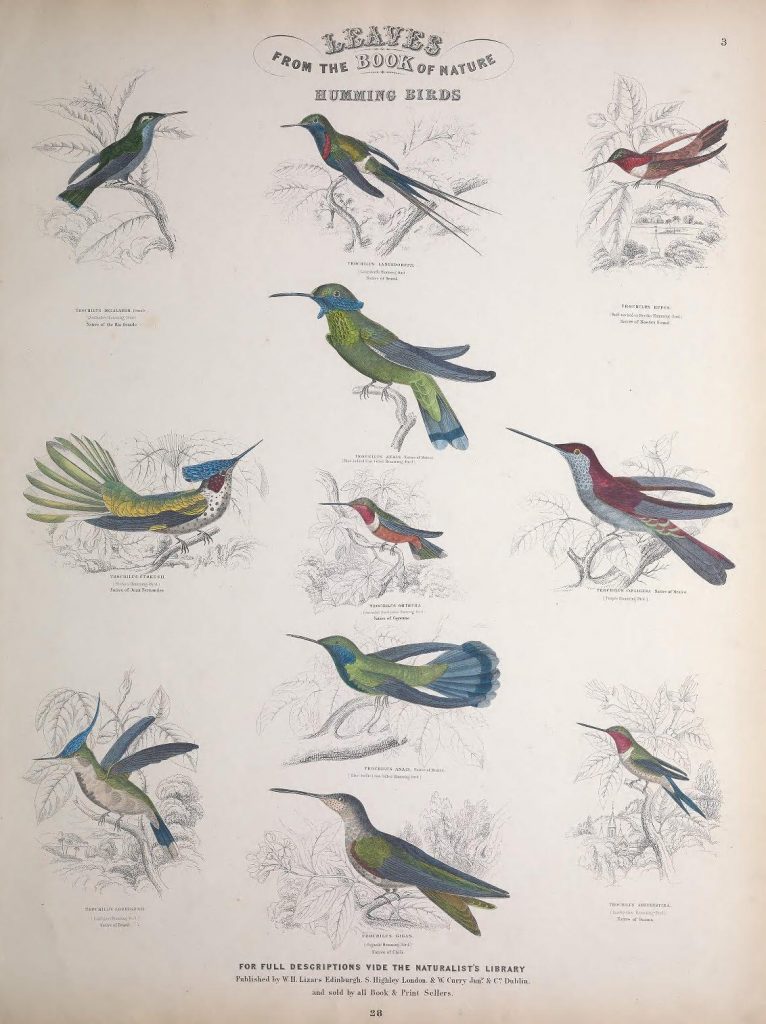

Garden of the Hōjō (Abbot Hall) of the Ryōanji Temple. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue,Volume 4.

Garden of the Hōjō (Abbot Hall) of the Ryōanji Temple. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue,Volume 4.

Edo-period’s highly literate and curious population found their interests fed by the emergence of commercial publishing in major cities. Nor did publishers miss the opportunity to venture into the thick of the travel craze, publishing travel books full of much needed and much desired information.

The idea of books about places was not new. However, earlier, books on places were mainly travelers’ personal journeys or poetic works related to places rather than books with facts about a place. This new type of books about a place was named meisho zue (Famous places illustrated). Meisho zue offered more accurate and objective descriptions of places with reader-friendly explanations. Sometimes issued in pocket-book size, it also provided information for travelers such as local highlights, historical anecdote and literary associations as well as more practical information like local customs, events and specialties, lodging, restaurants, distance between places and locations of hot spring. Thanks to mid-18th century improvements of printing techniques meisho zue were generously embellished with beautiful, full-page illustrations. Illustrations, often from a bird’s-eye point of view, were a key element for this new genre, meisho zue. The producers of meisho zue used abundant illustrations and easy reading material to attract readers’ attention to the strange places and things covered in the books. Moreover, these books served as entertainment for armchair travelers and as welcome souvenirs for non-travelers. Meisho zue was the “LONELY PLANET” of 19th-century Japan.

A rice cake shop. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 3.

A rice cake shop. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 3.

By the mid-19th century many kinds of meisho zue were published. Some, such as Yamato Meisho Zue 大和名所図会 (Famous Places in Nara, 1791), focused on certain geographical locations. Others featured particular subjects as in Nihon Meizan Zue 日本名山図会” (Famous Mountains in Japan, 1812) and Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue 日本山海名産図会” (Famous Local Products in Japan, 1799). Some depicted local events and daily life within a city as in Tōto Sumidagawa Ryōgan Ichiran 東都隅田川両岸一覧” (Views of Sumida River Banks in Edo, 1781). Readers could also enjoy a virtual trip to China via Morokoshi Meishō Zue 唐土名勝図会” (Famous Places in China, 1802).

The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Library of the Smithsonian Libraries has two typical meisho zue in its Rare Book Collection. They are Miyako Meisho Zue 都名所図会” (Famous Places in Kyoto, 1780) and Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue 都林泉名所図会” (Famous Gardens in Kyoto, 1799). The author of both works was Akisato Ritō 秋里籬島 (active 1780-1814), a literary author and haikai poet from Kyoto.

Yamahoko float of the Gion Festival. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 2.

Yamahoko float of the Gion Festival. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 2.

Akisato played an important role in the development of meisho zue. He invented the term “meisho zue” and published his first, Miyako Meisho Zue (Famous Places in Kyoto) in 1780. The popularity of his first book promoted the publishing of numerous meisho zue thereafter and contributed to the commoners’ travel boom. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Akisato authored dozens of meisho zue on many sightseeing spots. To assure correct descriptions, he visited each place, taking illustrators with him to help document the information he collected during these visits.

Miyako Meisho Zue (Famous Places in Kyoto, 1780) was published in 6 parts in 11 volumes. The illustrations were done by Takehara Shunchōsai 竹原春朝斎 (-1800). The work covered not only popular spots in the center city but also the suburban areas of Kyoto, including information on local products, festivals, events and seasonal scenes as well as daily life and customs. The illustrations were often accompanied by famous classical poems, waka associated with the place. It became an all-time best seller, having sold four thousand copies, and was still reprinted six years after its initial publication in 1780.

Daimonji (the Great Bonfire) Festival. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 4.

Daimonji (the Great Bonfire) Festival. Miyako Meisho Zue, Volume 4.

Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue (Famous Gardens in Kyoto, 1799), in 5 parts in 6 volumes, was illustrated by three artists, Sakuma Sōen 佐久間草偃 (-1814), Nishimura Chūwa 西村中和 (active late 19th century) and Oku Bunmei 奥文鳴 (1773-1813). It introduced well-known gardens many of which are from temples and shrines in Kyoto. The text also included detailed historical information on the temples and shrines and listed religious art and artifacts which they owned. The well-researched textual information and rich illustrations made Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue an important historical source for Kyoto gardens of Edo Japan.

Summer evening scene of Shijō Riverbank. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue, Volume 1, Part 2.

Summer evening scene of Shijō Riverbank. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue, Volume 1, Part 2.

Digitized versions can be viewed here:

Miyako Meisho zue: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/miyako-meisho-zue (v. 2-6)

Miyako Rinsen Meisho zue: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/miyako-rinsen-meisho-zue

Recommended Reading:

Plutschow, Herbert E. A Reader in Edo Period Travel (Global Oriental, 2006)

Sandler, Mark H. “The Traveler’s Way: Illustrated Guidebooks of Edo Japan,” Asian Art, vol. 5, no. 2: pp. 31-35 (Spring 1992)

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos. Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan (Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1994)

Detail of boat trip for cherry blossom viewing in Arashiyama. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue, Volume 5.

Detail of boat trip for cherry blossom viewing in Arashiyama. Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue, Volume 5.

Delivery Cars: Making the Rounds in the Early 20th Century

For the past few months, many Americans have relied on delivery vehicles to transport essential goods, like food and other household products. And okay, maybe a non-essential pair of shoes, a game or a book or two. But delivery vehicles are nothing new. Let’s take a look at delivery cars through the lens of this early 20th Century trade catalog.

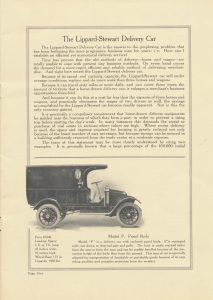

The catalog is titled Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car (circa 1914) by Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co. People always seem in search of faster and more efficient ways of doing things. This catalog begins by describing benefits of using a motor vehicle for deliveries rather than a horse and wagon.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, title page.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, title page.

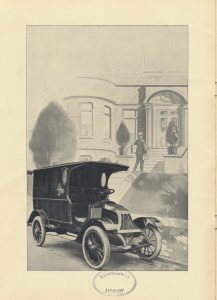

Imagine some thoughts that might have crossed the mind of a business owner transforming his business from horse and wagon to motor vehicle deliveries. How much of an impact would this have on the business? Would a motor vehicle provide more efficiency? Would it be cost-saving?

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 2, delivery car parked on street while a man delivers boxes to a house.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 2, delivery car parked on street while a man delivers boxes to a house.

According to this catalog, the Lippard-Stewart Delivery Car had the ability to travel 60 or more miles per day and do more work than three horses and wagons. A motor vehicle brought more dependability by being able to work in all types of weather and all hours of the day. This also resulted in wider territories to serve.

The horse and wagon delivery method required a stable to house horses near the place of business. That way the horses were nearby and did not have a long journey before the delivery day even began. On the other hand, if a motor car was used for deliveries, there were more options of rental space for storage of the car in various locations at various distances from the business, possibly resulting in lower costs.

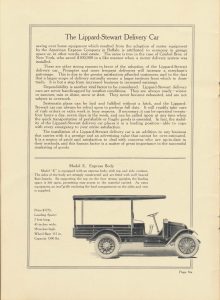

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 4, Model S, Stake Body delivery car.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 4, Model S, Stake Body delivery car.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co. offered several bodies for delivery cars. One type was the Model S, Stake Body, shown above. The Stake Body had an open platform for storage with removable stakes, cross bars, or chains enclosing the platform. This style provided extra storage space for material goods because the platform extended beyond the rear wheels.

The Model P, Panel Body, shown below, was enclosed with rear doors or a drop tail gate and grille. It was possible to reach the storage area from either the front or rear. Being fully enclosed, the storage area was protected from unfavorable weather conditions. Its “easy riding qualities” was described as a benefit when transporting breakable goods.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 5, Model P, Panel Body delivery car.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 5, Model P, Panel Body delivery car.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 6, Model E, Express Body delivery car.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 6, Model E, Express Body delivery car.

Another body was the Model E, Express Body. As shown above, this model included an open loading space with a roof and iron grille on the sides and rear. This allowed easy access to the goods stored in the loading area. The Express Body as well as the Stake Body and Panel Body all had a capacity of 1500 pounds.

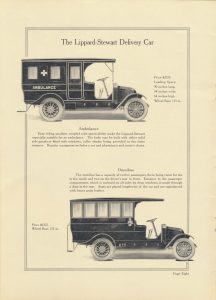

Besides delivery cars, this company also offered specialty vehicles. The Ambulance is shown below. It was equipped with a cot and chairs for both a physician and nurse. The sides were either solid panels or included windows with roller shades. Its ability for speed and “easy riding qualities” made it especially useful as an ambulance.

The Omnibus, also shown below, had the capacity to transport a group of people. The front driver’s seat allowed enough space for two people to sit while 10 additional people were seated lengthwise in the enclosed passenger compartment. A rear door provided entry and exit from the passenger compartment.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 8, Ambulance and Omnibus.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 8, Ambulance and Omnibus.

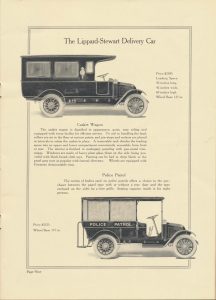

Other specialty vehicles included the Casket Wagon and Police Patrol, both illustrated below. The Casket Wagon included a removable rack to divide the back compartment into an upper and lower section. It came with rollers, pin-stops, and sockets to assist with loading and securely holding caskets. Side windows were equipped with black broad-cloth.

The Police Patrol, below, had the capacity to seat eight people inside. It was available as a panel style vehicle with or without a rear door or as an enclosed style vehicle with wire grille sides.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 9, Casket Wagon and Police Patrol.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 9, Casket Wagon and Police Patrol.

The catalog continues with details about construction, parts, and specifications of the motor vehicles. Depending on the model, delivery vehicles were available in shades of blue, red, or green. For a specialized vehicle, such as the Ambulance, Omnibus, or Police Patrol, it was available in any color desired. The Casket Wagon was available in either black or pearl gray.

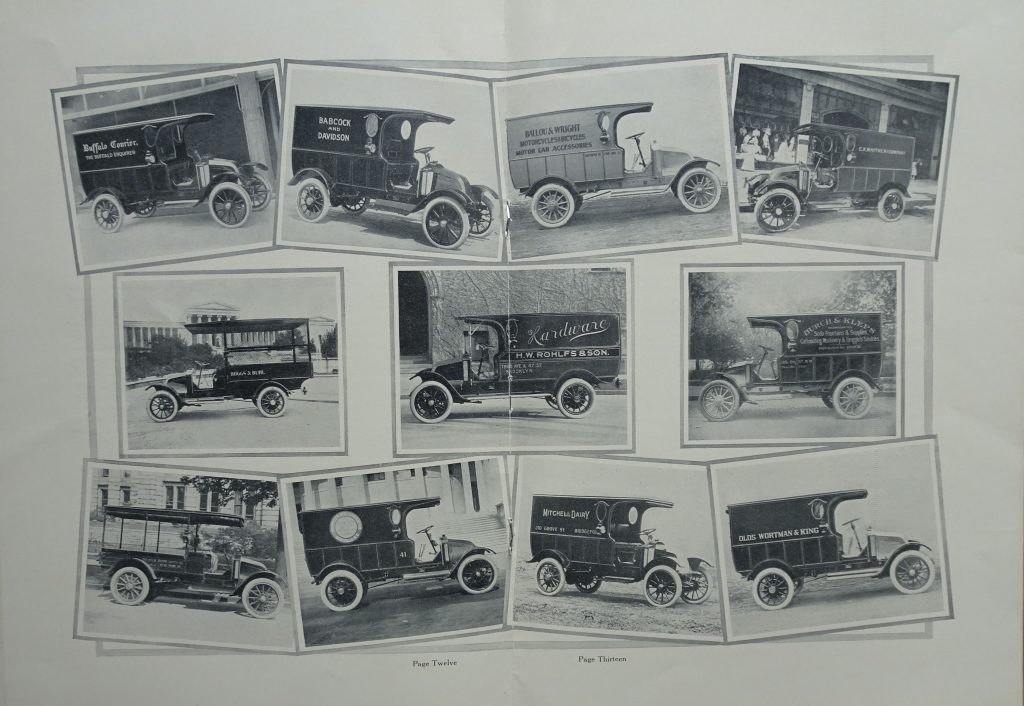

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, pages 12-13, delivery cars for various businesses.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, pages 12-13, delivery cars for various businesses.

As shown in the illustrations above, various businesses used the motor delivery car. This included dairy, ice cream, newspaper, hardware, and other businesses supplying goods and materials. The catalog ends with testimonials from some of the companies. Letters mention satisfaction with the delivery car’s abilities to carry heavy loads, cover many miles, navigate difficult road conditions due to weather, and its overall operation even for inexperienced users.

Howard & Barber Co. of Derby, Connecticut wrote on July 26, 1912: “…This spring after the heavy April rains the country roads were never in such bad condition and certainly the car had a thorough test along this line but in spite of these conditions it did the work perfectly.”

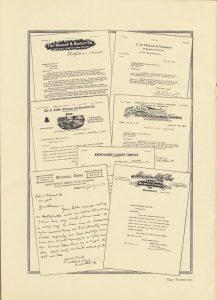

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 22, testimonials/letters of companies who used the delivery cars.

Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co., Buffalo, NY. Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car, circa 1914, page 22, testimonials/letters of companies who used the delivery cars.

Lippard-Stewart: The Delivery Car (circa 1914) and other trade catalogs by Lippard-Stewart Motor Car Co. are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Abiding Attachments: Artist Emma Stebbins and Actor Charlotte Cushman

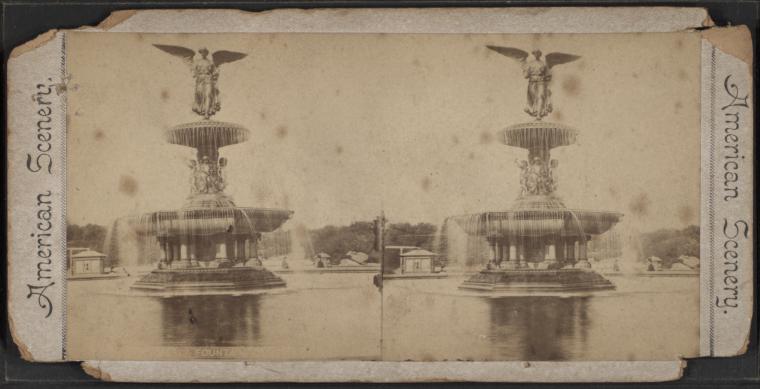

Few who walk past the Bethesda Fountain in New York City’s Central Park know the history behind the angel statue, standing high atop the fountain with wings outstretched. This sculpture, called Angel of the Waters, has been the backdrop for many movies and TV shows. The sculpture was made by a wealthy New York sculptor named Emma Stebbins, an artist featured in an album of cartes-de-visites (small, collectible photo cards) of notable 19th century American artists, located in the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library collection. Little is known about Stebbins, even though Angel of the Waters, as noted recently in the New York Times, was “the first public art commission ever awarded to a woman in New York City.”[i] However, what is known about Stebbins has been gleaned from the letters and press coverage of her relationship with famous American actress Charlotte Cushman.

“Bethesda Fountain, Central Park.” Courtesy of New York Public Library.

“Bethesda Fountain, Central Park.” Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Emma Stebbins was born into a life of affluence as the daughter of the wealthy banker, John L. Stebbins. The wealth and clout of her family allowed her to devote her life to a career of art, which was not often the case for women of lesser means. At the age of 42, Emma Stebbins travelled to Rome in 1857 and met with fellow American sculptor Harriet Hosmer who had arrived in Rome five years earlier.[ii] In Rome, Hosmer was part of a social circle of other independent (and often wealthy) women artists and creators, most of which lived in an apartment in Rome established by American actress, Charlotte Cushman. Cushman was particularly supportive of Hosmer and her work, using her celebrity to advocate for the sculptor. Stebbins was welcomed into this community of women and almost immediately began a romantic relationship with Cushman that would last for the rest of their lifetimes. In an 1858 letter to Emma Crow, Cushman alludes to marrying Stebbins noting “Do you not know that I [Cushman] am already married and wear the badge upon the third finger of my left hand?”[iii]

Carte de VIsite of Emma Stebbins from American Art/Portrait Gallery Library

Carte de VIsite of Emma Stebbins from American Art/Portrait Gallery Library

As the couple split their time between the United States and Europe, Cushman served as Stebbins’s greatest advocate and worked hard to promote her partner’s art. In one instance, Cushman rallied for Stebbins to win an 1859 commission to create a sculpture of Horace Mann that would be placed in front of the State House in Boston. Stebbins ultimately won, much to the dismay of Hosmer who no longer received the same support from Cushman.[iv] The most famous commission that Stebbins would receive would be for the aforementioned statue Angel of the Waters that would sit at the center of the Bethesda Terrace in New York’s Central Park.”[v] As reviews of the statue began to appear in the newspaper, Cushman was very vocal in both her admiration of Angel of the Waters as well as her disdain for those who were critical of it. As Cushman was retired (though she was happy to make special performances) it was noted by Cushman biographer, Lisa Merrill, that the actress spent more time on Stebbins’s career than her own at the end of her life. [vi] Ironically, after Cushman died in 1876 Stebbins spent much of the rest of her life on creating a biography of Cushman’s career, published in 1879, and ultimately stopped creating art until her death in 1882.

This focus on Cushman at the end of Stebbins’s life, as well as what seemed to be a general disinterest in self-promotion, helps explain the lack of information on Stebbins from her own voice. What is known comes mainly from letters written by Cushman to others and from newspapers of the time. Many American newspapers discussed them interchangeably whether they reported on Cushman’s acting tours or Stebbins’s sculptural works. Many examples of this can be found in the artist file for Stebbins located in the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library’s Colonel Merl M. Moore, Jr. Files, a collection of artists files focused on 19th century American artists that consist mainly of photocopies of 19th century American newspapers and magazines. For instance, Stebbins’s file included a clipping from the November 17th Boston Daily Evening Transcript from 1869 that reported an anecdote about how the couple took care of each other when they were ill: “I am sorry to say, however, that Miss Stebbins has been quite ill. She was with Miss Cushman during all of her cruel suffering, and of course, after the worst was over, Miss Stebbins’s nervous system was completely prostrated.”

The discussions of the relationship between Stebbins and Cushman in newspapers seem to celebrate the closeness and camaraderie of the couple without referring to it as a true romantic relationship which at the time would, of course, be considered taboo. However, Harriet Hosmer biographer, Kate Culkin, noted that, at this time, there was a certain “cultural acceptance of intense female relationships.”[vii] In part this “acceptance” came from the increasing occurrence of privileged women choosing to live with other women often for the sake of their career and independence. This allowed many lesbians to live together as couples under the guise that they had intimate, but platonic, relationships.

Another source of information about Stebbins is a scrapbook compiled by one of her relatives (now in the collection of the Archive of American Art) of images and newspaper clippings about the artist’s career. In the scrapbook, amid the photos of statues and hand written notes, there is a clipping of Stebbins’s obituary from the New York Tribune. While much of the clipping celebrates Stebbins’s artistic accomplishments, the entire last paragraph is devoted to the ways that her relationship with Cushman defined much of her life:

Miss Stebbins’s name is indissolubly linked with that of her friend Charlotte Cushman, with when she formed a close intimacy soon after taking up her residence in Rome. They lived together, travelled together and worked together for many years. It was one of those romantic and abiding attachments which indicate a genius for friendship. Miss Stebbins watched over her friend in her late illness and became her loving and appreciative biographer. Since the death of the great actress her own health has been declining.[viii]

[i] Jennifer Harlan, “Overlooked No More: Emma Stebbins, Who Sculpted an Angel of New York,” The New York Times, May 29, 2019.

[ii] History Project, Improper Bostonians: Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to Playland (Boston: Beacon Press,1998), 58.

[iii] Lisa Merrill, When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 211.

[iv] Kate Culkin, Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), 96.

[v] Merrill, When Romeo Was a Woman, 201.

[vi] Merrill, 202.

[vii] Culkin, Harriet Hosmer, 63.

[viii] F, “The Late Miss Emma Stebbins.” New York Tribune, November 2, 1882.

Abigail May Alcott: Little Woman

With Mother’s Day in our recent memory, it’s the perfect to remember one of the most familiar and loved matriarchs in American literature: Marmee, from Little Women. The American Art and Portrait Gallery Library has some of the most recent scholarship on Abigail May Alcott, mother of Louisa and the inspiration for Marmee. It comes courtesy of historical biographer Eve LaPlante.

With Mother’s Day in our recent memory, it’s the perfect to remember one of the most familiar and loved matriarchs in American literature: Marmee, from Little Women. The American Art and Portrait Gallery Library has some of the most recent scholarship on Abigail May Alcott, mother of Louisa and the inspiration for Marmee. It comes courtesy of historical biographer Eve LaPlante.

LaPlante is a descendant of Louisa May Alcott and discovered the letters that were the basis of much of her scholarship for both books in a family trunk. Her books Marmee & Louisa (2012) and My Heart is Boundless (2012) use Abigail May Alcott to provide insight into the life and heart of this remarkable matriarch. She also makes the argument that Abigail’s childhood was an inspiration for the lives of the March sisters, as well as the lives of Louisa and her siblings. With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at the “Little Woman-hood” of Abigail May Alcott, as described in Marmee & Louisa.

A Childhood Touched By Tragedy

Abigail May was born in Boston on October 8, 1800, the youngest of eight children, to Joseph and Dorothy Sewall May. The family was close-knit, loving, but had also endured several hardships that shaped the family’s character before Abigail was born. In 1798 Abigail’s father, Joseph May, lost the family fortune. His business partner invested heavily in a fraudulent scheme known as the Yazoo land scandal. After the bankruptcy and “mental suffering” that followed, Joseph May resolved to never again pursue material wealth, refusing other investment opportunities that came later and keeping the family in modest circumstances. (LaPlante, 15). This change of fortune is something the fictional March sisters also experienced:

“Abigail knew her father only after his business failure. But her oldest siblings, like the elder sisters in Little Women ‘could remember better times.’ In the novel one sister asks another ‘Don’t you wish we had the money papa lost when we were little.’” (LaPlante, 15).

Her father coped with the change with a new emphasis on duty and scorn toward materialism. These ideals were helped along by the support of his wife’s wealthy family. Abigail’s mother, Dorothy Sewall May was from a prominent New England family–one of the era’s “Boston Brahmins.” She was a cousin to Abigail Adams and counted revolutionary John Hancock as brother-in-law. (LaPlante, 15).

Financial troubles weren’t the family’s only worry; Abigail’s parents also endured the loss of five babies before she was born. Additionally, when she was a toddler, Abigail’s 6-year-old brother died in an accident. This incident had a great impact on the entire family and led to Abigail growing up with four sisters and one brother, Sam Jo. According to LaPlante this “fundamental May quintet” was Louisa’s inspiration for the March sisters and Laurie. (LaPlante, 10)

Wanting More

As she grew, Abigail’s great desire was to be educated. While her mother’s desire for some education for her daughters was mildly progressive for the day, Abigail had academic ambitions that went beyond the domestic sphere. According to LaPlante (19):

“She did not relish a marriage like her aunt’s and mother’s…she longed for the experiences of her brother Sam Jo. She wished to read history and literature, learn Latin and Greek, and use her mind to improve the world one as he was encouraged to do.”

Despite her ambitions, Abigail was a sickly child and found her education often interrupted by illness. Yet even through this difficulty her parents “indulged” her with a private tutor in her teen years. Dorothy Sewall May wanted daughters who were “educated as fit companions to a man,” a somewhat progressive attitude in a time when women were widely believed to be intellectually inferior to men.

Her educational ambitions had stronger support from her brother Sam Jo. The pair remained close as they grew up and When the time came for him to attend the prestigious boys’ schools of his day, Sam Jo encouraged Abigail to read his books and think for herself. This continued when he was in college, the pair discussed John Locke and the humanities in their correspondence. Another sibling, Louisa, also taught Abigail by mail: coaching her in grammar and writing. (LaPlante, 22-3)

A Small Rebellion

By the time Abigail was seventeen, she was looking for ways to become a teacher while her parents were trying to find her a husband. Much of that year was spent with the family’s reaction to the rejection of her cousin’s marriage proposal. When tensions grew too great at home, Abigail went away to study with family friends. She returned only after her cousin had died and her father agreed not to try and match her with eligible young men. (LaPlante, 29)

Not long after her return home, Abigail and her eldest sister, Louisa pursued the idea of running a school in their family home. This was derailed when, in 1821, Louisa accepted a marriage proposal. Then, tragedy shaped Abigail’s life again: her youngest sister died, leaving behind a toddler nephew and infant niece, that fell into Abigail’s care, effectively putting an end to her dreams of being an educator. Perhaps that’s the reason that Louisa May Alcott ends her novel with the celebration of Marmee’s birthday at the school Jo founded. It could have been her way of honoring her mother’s youthful ambitions.

Abigail’s young life shows us just how it was difficult for women in the early 19th century to pursue anything other than the path of domesticity; how bright and creative little women often became good wives. Yet even as society struggled to value the contributions of wife and mother, Abigail May Alcott was a woman of principle: as a supporter of education of girls and an early supporter of abolition and emancipation for enslaved people (LaPlante, 52). She used her power where she could, even in marrying Bronson Alcott a penniless teacher with matching ideals—over the disapproval of her parents.

Through a loving marriage marked by frustration, financial hardship, and tragedy, Abigail maintained her beliefs, passing them on to her daughters. Her legacy lives on, not just through the goodness of Marmee but through the principle and ambition of all the March sisters—and their real-life equivalents. They got it from their mama.

Breaking the Cycle: the Kittie Knox story

In a society that largely relies on motor vehicles for transportation, or even for sport, it may seem difficult to understand why it was so monumental for a plucky twenty-year-old woman to be allowed to participate in bicycle races, meets and other activities involving the sport. However, what transpired between the young woman and many cycling critics would prove to be a landmark in both the history of gender and racial issues.

Katherine Towle Knox, known as Kittie, was born on October 7, 1874 in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of a white mother, Katherine Towle, and an African American tailor, John H. Knox. When Kittie was just around seven years old, her father passed away from an unknown cause. In the wake of her father’s death, Kittie, her mother, and her older brother Ernest moved to the West End of Boston on the corner of Irving and Cambridge streets. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, this particular area in Boston was home to an array of impoverished African Americans and immigrants. While the West End of Boston struggled financially, it seemed to be quite progressive in its successful integration of many different cultures in one neighborhood. Kittie found work as a seamstress and her brother found work as a steamfitter in an attempt to create a better life in an era that seemed to only create limitations for people of color.

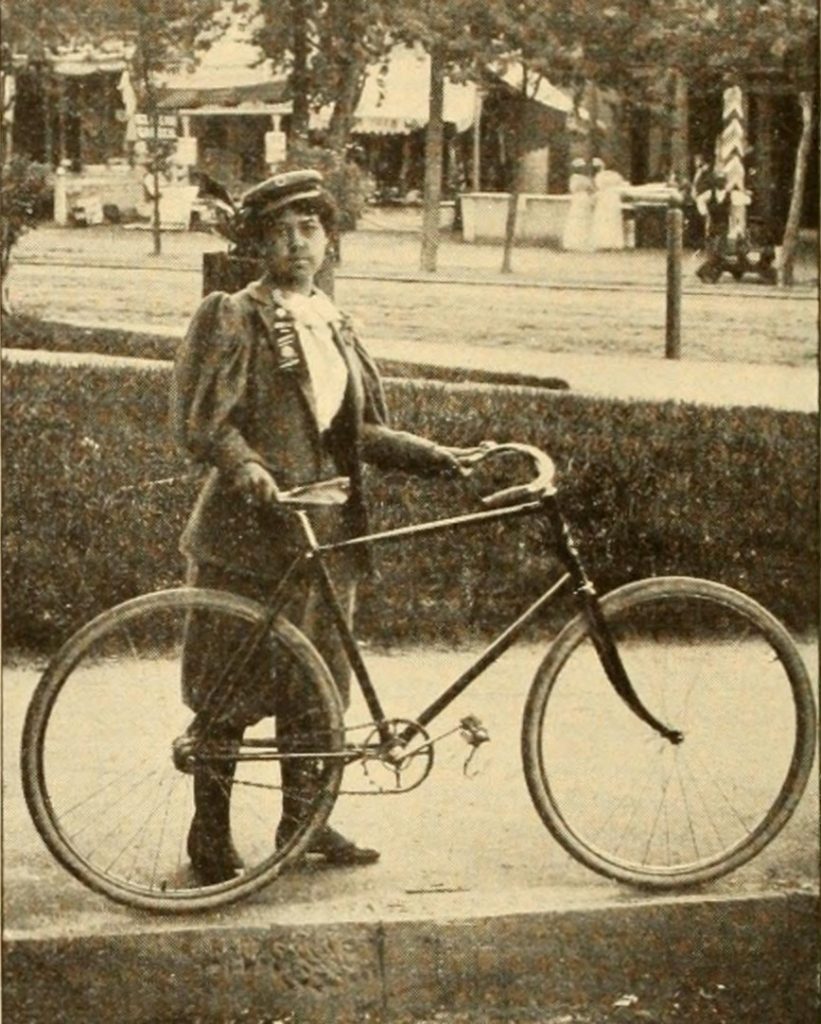

Kittie Knox at Asbury Park. Referee and Cycle Trade Journal, v 15, no.12.

Kittie Knox at Asbury Park. Referee and Cycle Trade Journal, v 15, no.12.

Kittie began to show interest in cycling early on in her life. After saving enough money from her job as a seamstress to buy a bicycle, Kittie became well-known in her neighborhood for her various outings. It was said that Kittie was a part of the Riverside Cycle Club, along with a few other friends and fellow female cycling enthusiasts. There is some speculation about whether or not they were actually considered card-carrying members, due to the general consensus at the time that women were not allowed to participate in a male-dominated sport. Kittie would continue to attract the attention of other cyclists as she began to participate in meets, winning many of the bicycling competitions she took part in.

In 1893, Kittie was accepted as a member of League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W). In 1894, the L.A.W. changed its constitution to include the word “white”, creating a “color bar” for the organization. This caused many members to question the legitimacy of Kittie’s membership. In his book Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1900 , Lorenz J. Finison details some of Kittie’s experiences during this time.

Cover of Boston’s Cycling Craze by Lorenz J. Finnison.

Cover of Boston’s Cycling Craze by Lorenz J. Finnison.

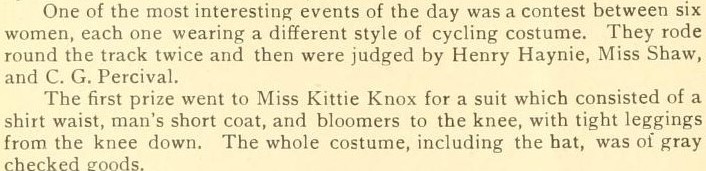

Despite her controversial membership, Kittie was a popular candidate in competitions that featured female L.A.W. members sporting their best looks. In the 1895 edition of The Bearings, a cycling journal, a section details Kittie’s first-prize win at an event in Waltham, Massachusetts:

Description of Knox’s winning costume in The Bearings, v. 11. No. 24. July 11, 1895.

Description of Knox’s winning costume in The Bearings, v. 11. No. 24. July 11, 1895.

Kittie became known for both her unique style and elegant riding technique but her appearance was frequently scrutinized by journalists. While the newspapers failed to describe in great detail how attractive any of the male cyclists were, they succeeded in giving an account of Kittie’s physical appearance and wardrobe in nearly every meet covered. She was at times described by journalists as a “comely colored maiden”, “murky goddess of Beanville”, and “beautiful and buxom black bloomerite”. Kittie seemed to inspire colorful phrases regarding her color and gender, despite the fact that these aspects had nothing to do with her ability as a serious cyclist.

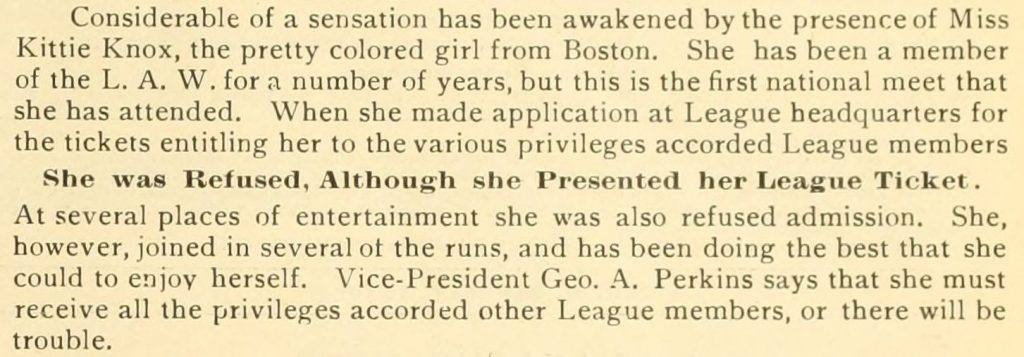

A particular incident in which Kittie showed her defiance occurred in July of 1895 when Kittie entered the annual meet at Asbury Park. It was reported that she was denied entry and was not recognized as a member of the L.A.W., despite being a card-carrying member. It was also reported that Kittie was denied service by restaurants and hotels while staying in New Jersey for the meet. This situation was promptly documented by The Referee and Cycle Trade Journal, as well as newspapers around the country:

Description of Knox’s trials at the Asbury Park meet in 1895.

Description of Knox’s trials at the Asbury Park meet in 1895.

Eventually, the issue of the “color bar” boiled over in the L.A.W. A battle ensued between the members who believed that the L.A.W.’s “white only” membership policy be upheld and those who felt segregation was wrong. In a July 1895 issue of L.A.W. Bulletin & Good Roads, L.A.W. stated that “Miss Katie [sic] Knox joined the League April 21, 1893. The word ‘white’ was put into the [L.A.W.] constitution, Feb. 20, 1894. Such laws are not and cannot be retroactive. We don’t know who it was that competed in the races and we know of no law that would keep a negro out of an open race, be he League member or not” (read a copy available through HathiTrust). After this statement was released, Kittie was accepted fully as a member, making her the first ever African American to be accepted by the League of American Wheelmen.

Kittie Knox’s story of courage in the face of racial tension helped desegregate the world of cycling and offered a hopeful vision for a future that accepts and supports diversity. Kittie is featured in several cycling journals held by the Smithsonian Libraries, such as the aforementioned The Referee and Cycle Trade Journal and The Bearings. Both journals can be found in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Digital Library. Much of her story is also detailed in the Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1900, which can be found in the National Museum of African American History and Culture Library.

Research from Home: Providing Resources to Smithsonian Scientists

As the world faces the global challenge of COVID-19, the Smithsonian Libraries is working to provide research services and resources to our users around the world. Whether it’s by joining virtual meetings with research teams, answering real-time questions from scholars in need, or providing quick and easy access to digital resources and electronic resources to researchers around the world, our team is pleased to continue contributing to important scholarship and scientific discovery, at the Smithsonian and beyond. As one National Museum of Natural History curator wrote, “The access to e-journals has made my stay-at-home work so much smoother.”

Dale Greenwalt in the field at the Kishenehn Formation fossil locality in Montana. Photo by: Jill Warren.

Dale Greenwalt in the field at the Kishenehn Formation fossil locality in Montana. Photo by: Jill Warren.

The Smithsonian Libraries has supported research at the Institution since its inception in 1846. Today, we are working to adapt to our “new normal,” and we will be here to work alongside our community in what comes next. While today we are focusing on providing digital support and access, many researchers find our help indispensable, both online and in person. One Smithsonian scientist, Dale Greenwalt, shares his experiences working with the Smithsonian Libraries and expresses his gratitude:

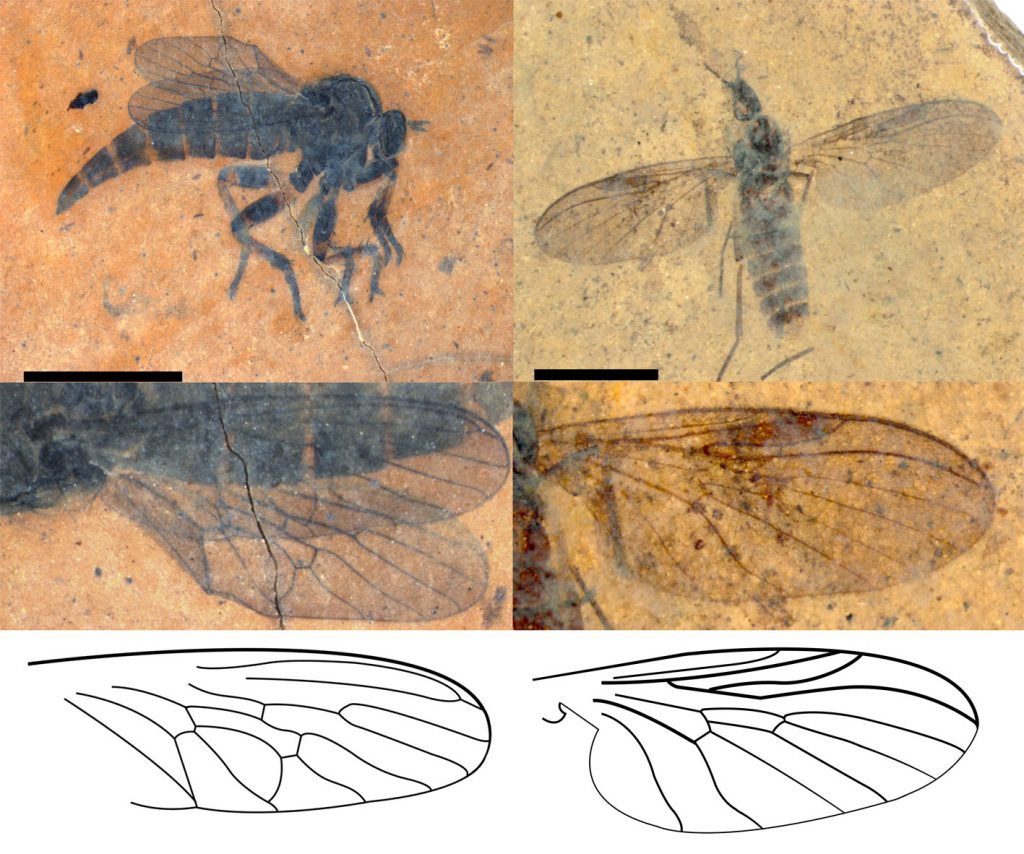

When the extinct wood gnat Sylvicola silibrarius was described from 46-million-year-old rock in northwestern Montana, it provided me with an opportunity to recognize and thank the staff of the NMNH libraries. The NMNH libraries are a treasure. The ability to simply descend a few flights of stairs and gain access to a large portion of the relevant scientific literature that has ever been published is critical to my work. When a new species is described, it must be compared to – and distinguished from – those previously described. In the case of Sylvicola, these totaled nine, some of which had been named in publications that dated back to 1803, 1890, 1904, 1907 and 1921. Many of the journals in which the descriptions were published went out of business in the 19th century; and one cannot simply e-mail the author of a 1904 paper and ask for a reprint! But most can be found in the Smithsonian Libraries.

Today, many scientific publications can be downloaded from the Internet. Many others however are not open source and the Libraries is financially unable to subscribe to every scientific journal – some of these journals cost nearly $20,000 a year! And many journals are published by small and obscure societies that have no presence in the World Wide Web. Thankfully, if a needed publication is not otherwise available, the Libraries can order a copy of the publication of interest through their Interlibrary Loan service – a copy of the publication is in my e-mail within a very few days.

My research would simply be impossible without the Smithsonian Libraries and librarians. And speaking of the latter, I have never in my professional career interacted with a more professional, friendly and helpful group of people. Without the Smithsonian Libraries and the folks who run them, my research would some to a standstill.

Sylvicola silibrarius Greenwalt, 2019 and Kishenehnoasilus bhl Dikow, 2019.

Sylvicola silibrarius Greenwalt, 2019 and Kishenehnoasilus bhl Dikow, 2019.

To learn more about Sylvicola silibrarius, please read our blog post here.

Want to help make research like Dale’s possible? You can support your favorite library or program here.

Art Deco: Graphic Design Resources at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library

This is the fifth in a series of posts about the Art Deco resources at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum library. Each post will highlight primary resources which contain the styles and designs of the Art Deco era. These resources are divided into seven categories- world’s fair publications, interior and architecture books, trade catalogs, graphic design, pattern books, and picture files. This guide is not an exhaustive summary and these featured resources are just a portion of what awaits Art Deco enthusiasts and researchers in the Cooper Hewitt library collection. We are grateful to Jacqueline Vossler and Joseph Lundy for their generous support of this project.

The Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum Library holds many graphic design pieces that help illustrate the Art Deco movement. Graphic designs during the Art Deco era embodied the velocity of new transportation, skyscrapers, and jazz music. Inspired by Cubism, designers borrowed the analytic and synthetic strengths of the style, filtering familiar realities through kaleidoscopic perspectives.

Figure 1. Cover of Pacific Southwest Exposition : official program , using a limited color palette highlighting the architecture and allure of the fair.

Figure 1. Cover of Pacific Southwest Exposition : official program , using a limited color palette highlighting the architecture and allure of the fair.

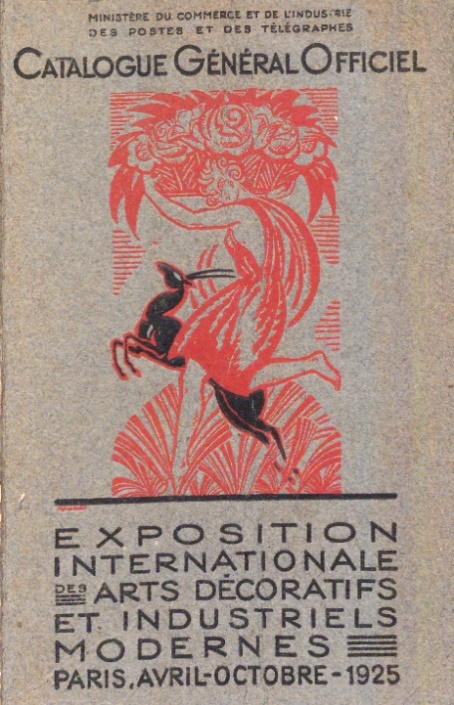

At the 1925 Paris Exposition, graphic design’s place in modern culture was recognized with a whole area devoted to the subject. Throughout the Library’s collection of World’s Fair materials, we see examples of Art Deco style in commemorative publications from the national and commercial pavilions alike. These publications became early vehicles for dispersing the design style.

Figure 2. .Cover of Catalogue général officiel : Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris, avril-octobre, 1925 , simple in its execution and featuring classic Art Deco motifs.

Figure 2. .Cover of Catalogue général officiel : Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris, avril-octobre, 1925 , simple in its execution and featuring classic Art Deco motifs.

Specific examples are featured here, yet this does not even scratch the surface of what there is to explore in the Cooper Hewitt’s collection. The images above are from the World’s Fair ephemera collection, discussed earlier in this blog series. The graphics at these fairs did not stop at the cover designs of souvenir books, though. Researchers can explore the style further in the ads and reports compiled by consumer product brands at the time.

Figure 3 and 4. Advertisements in Exposición Internacional de Barcelona 1929 : catálogo oficial. Celebrating the innovations of the era.

Figure 3 and 4. Advertisements in Exposición Internacional de Barcelona 1929 : catálogo oficial. Celebrating the innovations of the era.

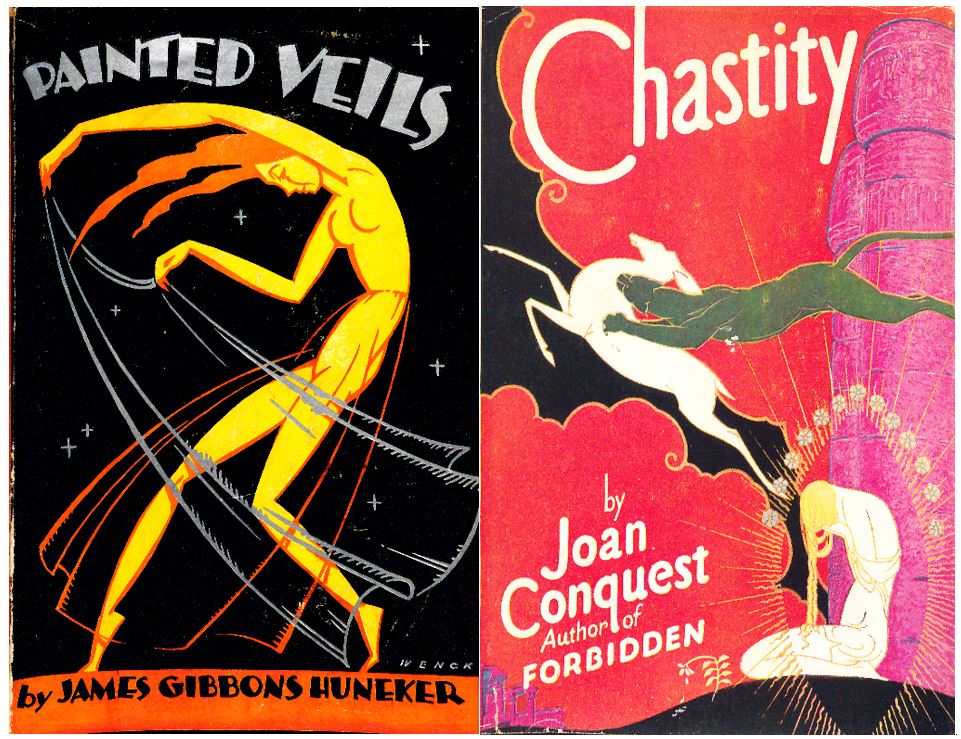

The Art Deco style soon graced book covers too. Within the Cooper Hewitt’s collection, several novels give an idea of the early 20th-century style but also what captured the attention and imagination of its readers from the 1920s or 30s. Books depict on their covers the fast-paced and lavish urban lifestyles that filled their pages.

Figure 5. Cover of Chastity: A Drama of the East by Joan Conquest, published 1929, New York.

Figure 5. Cover of Chastity: A Drama of the East by Joan Conquest, published 1929, New York.

Figure 6. Cover of Painted veils by James Huneker, published 1920, New York.

Figure 7. Cover of Illusion by Arthur Train, published 1929, New York.

Figure 7. Cover of Illusion by Arthur Train, published 1929, New York.

Art Deco’s balanced and geometric structure echoed throughout advertisements, book covers, buildings, trade catalogs, design, and decorative objects. Evidence can be found in books like Répertoire du gout moderne, which shows how pervasive these graphic trends were on design objects. Below are rugs with anonymous gymnasts gracefully soaring across rugs.

Figure 8. Plate 40 Répertoire du gout moderne published c. 1928-9, Paris.

Figure 8. Plate 40 Répertoire du gout moderne published c. 1928-9, Paris.

Art Deco’s flattened and abstracted aesthetics traveled internationally and encouraged growing appreciation towards abstraction as a universal ideal for communication beyond language. Many designers embraced these changes while finding an appropriately cosmopolitan way to capture the atmosphere. André Durenceau, a celebrated French illustrator who moved to Los Angeles in the late 1920s, published Inspirations around the time he arrived in the United States. The diverse portfolio displays his ability to work in the latest Art Deco style with bright colors, geometric shapes and exotic world influences.

Figure 9 and 10. Plates 18 and 24 of Inspirations illustrated by André Durenceau, published circa 1928, Woodstock, New York.

Figure 9 and 10. Plates 18 and 24 of Inspirations illustrated by André Durenceau, published circa 1928, Woodstock, New York.

Selected Bibliography:

Catalogue général officiel : Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris, avril-octobre, 1925

Call Number: N520.F8 P235 1925

Published/created: 1925, Paris, France

Official catalog for the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, France 1925. It includes illustrations of the decorative arts specifically featuring that of Spain, Italy, and the Yugoslavian theater. Available in French.

Pacific Southwest Exposition : official program

Call Number: T703.A1 P33 1928

Published/created: c. 1928, Long Beach, California

Official souvenir guide at the Pacific Southwest Exposition in Long Beach, California from 1928-9. Features illustrations and general information about architecture, exhibitions, and entertainment. Includes illustrations that show the Art Deco era obsession with light and waterworks. Available in English.

Exposición Internacional de Barcelona 1929 : catálogo oficial

Call Number: N4433. E99 1929

Published/created: 1929, Barcelona, Spain

Official souvenir guide at the Exposición Internacional in Barcelona, Spain, 1929. Features illustrations and general information about architecture, exhibitions, and entertainment. Available in Spanish.

Guide officiel de l’exposition internationale : coloniale, maritime et d’art flamand, Anvers, 1930

Call Number: T419.A2 G85 1930

Published/created: 1930, Bruxelles, Belgium

Official souvenir guide at l’exposition internationale in Antwerp, Belgium, 1930. Features illustrations and general information about architecture, exhibitions, and entertainment. Available in French.

Chastity: a drama of the East

Call Number: PR6005 b .O394 1929

Written by: Joan Conquest (Mary Eliza Louis Cooke)

Published/created: 1929, New York City, New York

A romantic fiction novel with a book jacket in the upmost Art Deco style attributed to Victor Beals.

Painted veils

Call Number: PS2044 .H4P3 1928X

Written by: James Huneker

Published/created: 1928, New York City, New York

A novel ruminating on the life and worldly behaviors on display in 1920s New York with a book jacket attributed to Paul Wenck.

Illusion

Call Number: PS3529 .R23I45 1929

Written by: Arthur Train

Published/created: 1929, New York City, New York

The story of a magician who no longer can decipher what is real and what is an illusion. Book jacket designer is unknown.

Répertoire du goût moderne

Call Number: NK2549 .R42 quarto

Published/created: c. 1928-9, Paris, France

Five volumes of illustrations featuring interiors and various ensembles of furniture and decorative arts. Many instances of the same space with different decorative design schemes.

Inspirations

Call Number: NK1535.D87 A4 1928 folio

Published/created: c. 1928, Woodstock, New York

Twenty-four plates with 128 illustrated compositions by André Durenceau. Featuring a diverse array of patterns from the increasingly connected world of the 1910s and 1920s.

Find the Perfect Video Meeting Background!

Whether shelter-in-place has you working from a studio apartment, in a home filled with kids, or a makeshift set-up at your dining room table, it can be hard to find a distraction-free background for the inevitable virtual meeting. Fear not! With over 9,000 digitized books and journals, we’re here to help make your next chat fun for both you and you colleagues. Create a custom background in Zoom, Teams, Webex, or other teleconference tool using public domain images from the Smithsonian Libraries.

Whether shelter-in-place has you working from a studio apartment, in a home filled with kids, or a makeshift set-up at your dining room table, it can be hard to find a distraction-free background for the inevitable virtual meeting. Fear not! With over 9,000 digitized books and journals, we’re here to help make your next chat fun for both you and you colleagues. Create a custom background in Zoom, Teams, Webex, or other teleconference tool using public domain images from the Smithsonian Libraries.

In a hurry? Below are 11 images ready to download. Just click on the image and save to your computer, then follow the instructions provided by the tool you are using. There’s also a brief description and link to each source for the inevitable question, “Where did you get that amazing background?!?”

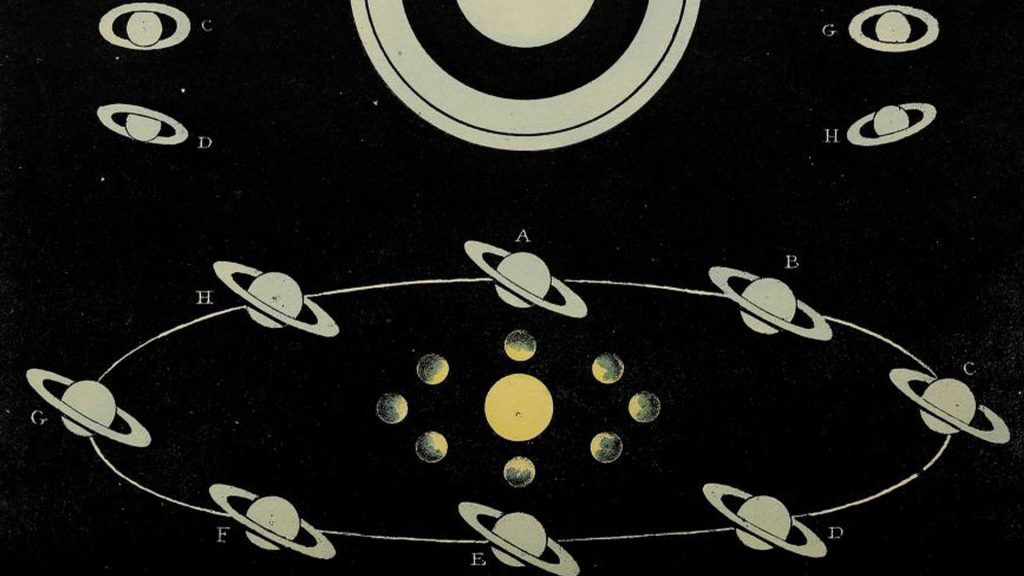

The Beauty of the Heavens by Charles F. Blunt (Tilt and Bogue, London, 1842)This book on popular astronomy contains over a hundred illustrated plates of astronomical phenomena. It also has lectures to accompany the plates, meant to be read to the whole family—which sounds quite relevant to today’s school-from-home, parent-as-teacher situation!

No. 50, Monoceros and Canis Minor

No. 50, Monoceros and Canis Minor

No. 20, Phases of the Planet Saturn

No. 20, Phases of the Planet Saturn

Watanabe Seitei (1851-1918) was a Japanese artist who blended traditional Japanese techniques with Western realism influences, resulting in gorgeous images of nature—primarily birds and flowers. Take that expense report meeting to the perfect picnic spot with these images!

[Dragonfly and flower]

[Dragonfly and flower] [Butterfly approaching flower]

[Butterfly approaching flower] [Bird on a branch]

[Bird on a branch]

Adelaide Alsop Robineau helped found this periodical for ceramics artists in 1889. A top ceramics artist herself, Robineau often featured the works of women artists, both as illustrators and throwers of pottery. In its issues you can find stellar examples of Art Nouveau, Arts & Crafts, and even some early Art Deco designs. Here are a few that would look great as a background:

Nasturtiums – Maud M. Mason, June 1903 Supplement

Nasturtiums – Maud M. Mason, June 1903 Supplement

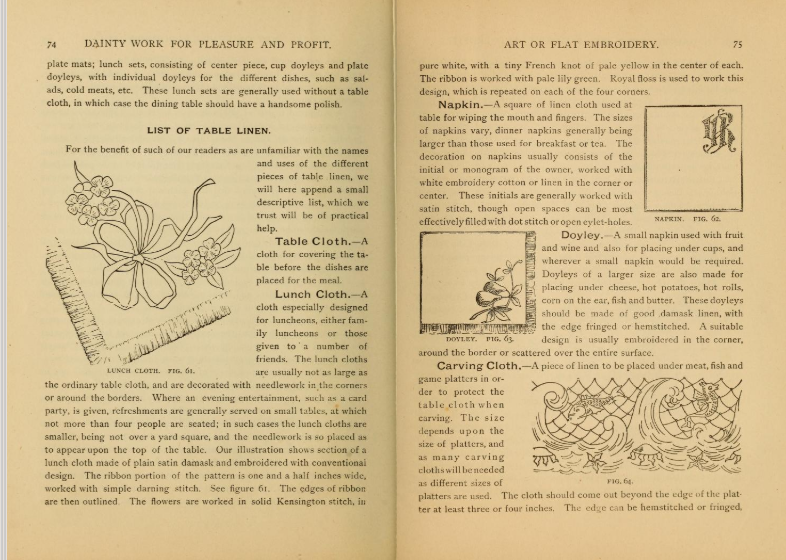

Peacock Study – F. Hurten Rhead, May 1904 Supplement

Peacock Study – F. Hurten Rhead, May 1904 Supplement

Double Violets – Marshal Fry, November 1900 Supplement

Double Violets – Marshal Fry, November 1900 Supplement

None of these fit your fancy? Find your own surprising image from our digital library, Image Gallery, or the Biodiversity Heritage Library to highlight instead!

Embroidery: Down the Needle Hole . . .

During this hectic time, it’s always great to be able to learn new and exciting things. From a recent social media discussion, I found out about an especially inspiring endeavor from our Smithsonian Family. For those not aware, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center created a Care Package. This care package features music, projects and inspirational material for communities during this time.

This inspired me to search the Libraries’ collection of digital books. I have found that our team has collectively made it easier to access our Digital Collections. In considering what we could add to a Libraries’ care package, I thought it would be interesting to include useful handicraft books such as sewing, knitting and the like, similar, and in the tradition of the historic Care Package seen in the National Museum of American History from 1962.

I found a title, dedicated to the “American Woman of the Day” a Mrs. Potter Palmer, (Bertha Palmer) who served as the President of the Board of the Lady Managers of the World’s Columbian exposition, the Dainty Work for pleasure and profit . It starts “We have tried in the following pages to include a love for home beautifying; to show how every home in this broad land can be rendered beautiful…” Embroidery became a vehicle for artistic expression as well as financial gain to women at this time. Herstory highlights this movement in a short blurb.

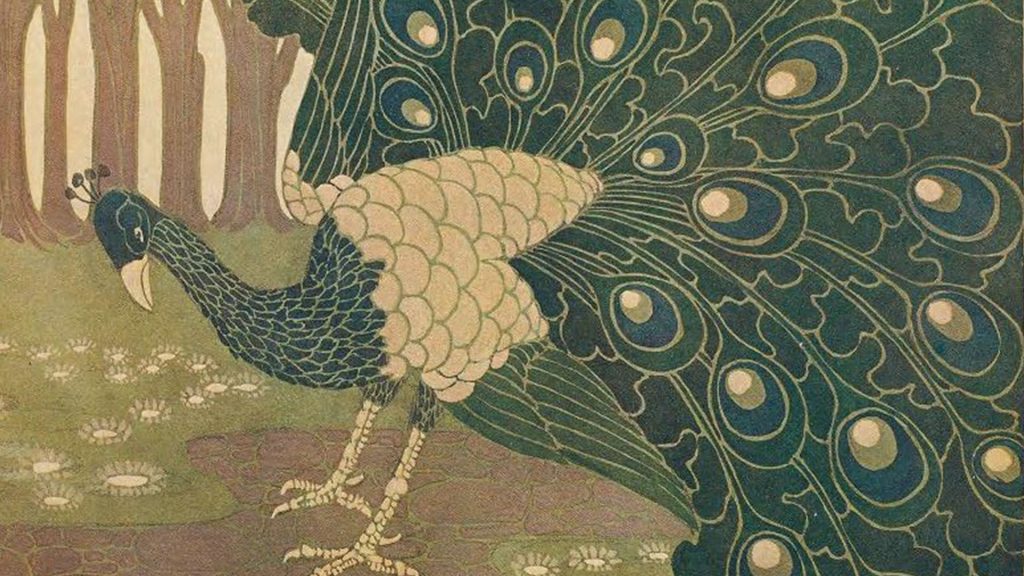

The book begins with a discussion on materials and delves into techniques and some example design patterns. As I continued to browse, I saw examples of the simple outline stitch and figure images of cording, close, and twisted outlines.

Page 28 &29 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

Page 28 &29 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

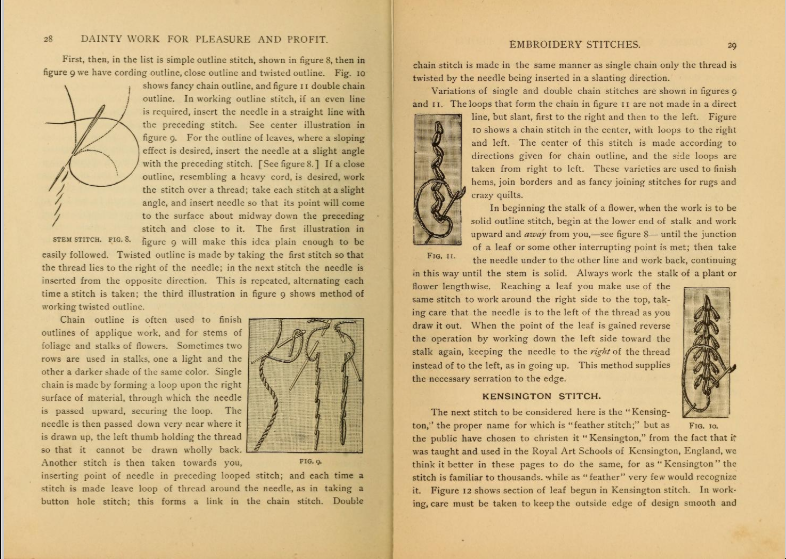

The book goes into detail about other versions of stitches to create patterns and designs such as flowers, stars and the infamous honeycomb, seen below. The greatness lies in its textual explanation (side anecdotes!) and the usefulness to American Women at the time. We have several of these types of books littered throughout the Smithsonian Libraries.

Pages 40 & 41 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

Pages 40 & 41 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

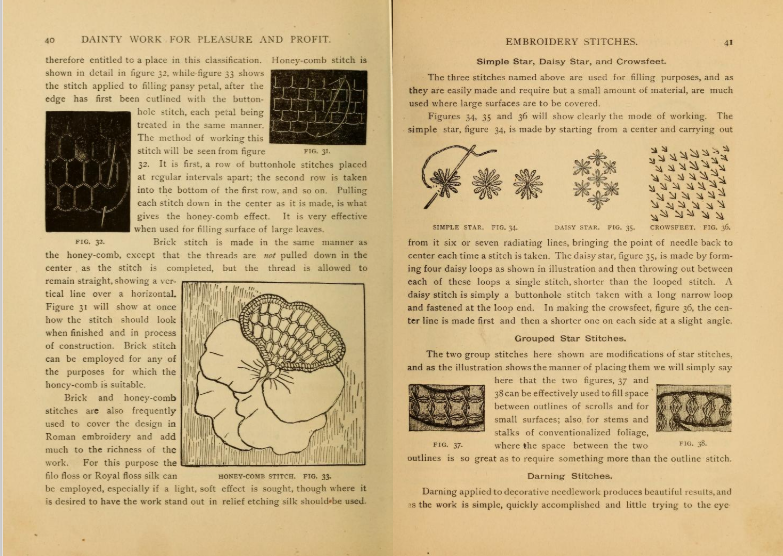

I finally came upon pages dedicated to “Art or Flat embroidery.”

Page 74 & 75 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

Page 74 & 75 of Dainty Work for pleasure and profit (1893).

Let it be known, I am not artistic, although I appreciate great artwork. It has been amazing to search through the Cooper Hewitt Textile Collections online and see several of their embroidery pieces, such as this counted stitch example acquired in 1925 from Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, early founders of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Entranced by this page and fascinated with the concept of “flat embroidery” I wondered as limited as my resources are, what I can do at home to replicate any of these amazing stitches and put them to use. Luckily, I came upon this “handi hour” crafting video of embroidering on paper from the Smithsonian American Art Museum!

I only had some paper, a sewing needle and black thread but it worked. I gathered my supplies and 15 minutes later Voila! I may need to buy correct material for a better art project, but I thought it was a great first attempt. Maybe it will be a second career choice! Have a great day everyone!

Others handicraft titles to explore in our Digital Library:

- Alphabete für die Stickerin : A German book from 1900 filled with embroidery patterns.

- Home Decoration: A book from 1881 that includes needlework instruction as well as tips for crafting draperies and wood carving.

Digital Jigsaw Puzzles

Need a fun mental break? We’ve created six digital jigsaw puzzles through Jigsaw Explorer that feature a few favorite images from our collection. Play them right here on our blog or use the links to expand an individual puzzle. Each puzzle is set to contain about 100 pieces, but they are customizable for any skill set. Hit the question mark icon on a puzzle for more information. We’ve tested these with staff (and kid volunteers!) and hope you enjoy them as much as we did!

All of these images are freely available through our Image Gallery, Digital Library or Biodiversity Heritage Library. Feel free to explore, download other images and maybe make your own boredom buster!

“The Lilac” from Eugene Grasset’s La plante et ses applications ornementales (1896).

A stunner of a book, Grasset’s design patterns focus on plants and flowers. It was intended to promote the Art Nouveau style.

Play online: https://jigex.com/CsBd

“The Lilac” from Eugene Grasset’s La plante et ses applications ornementales (1896).

“The Lilac” from Eugene Grasset’s La plante et ses applications ornementales (1896).

Jigsaw Puzzle

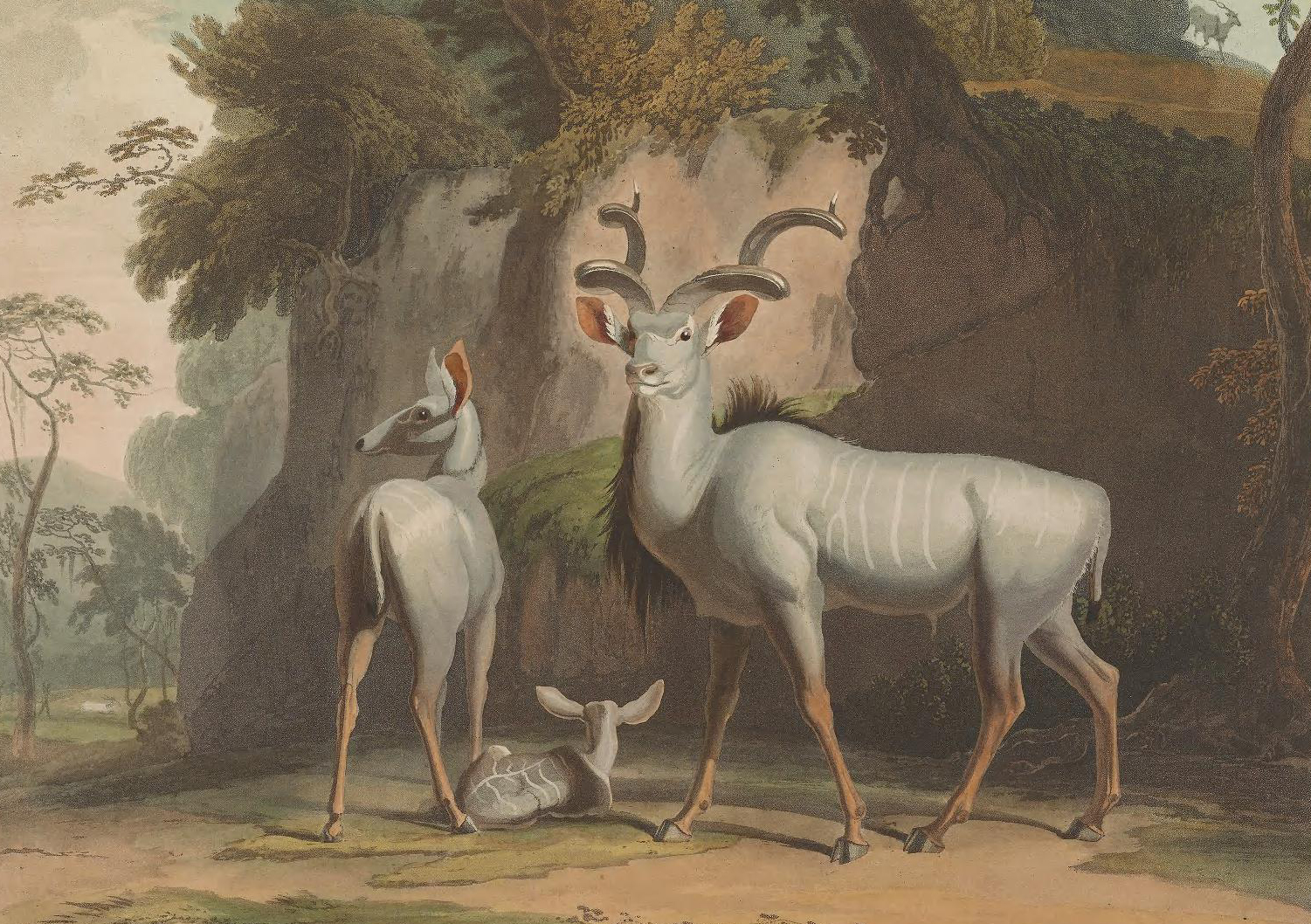

“The Koodoo” from Samuel Daniell’s African Scenery and Animals, 1804-05.

The kudu is a type of spiral-horned antelope. It’s one of many species (some now extinct) featured in African scenery and animals (1804-05), available in the Biodiversity Heritage Library. These hand-colored aquatint plates present artwork by Samuel Daniell, produced during an expedition to Africa at the end of the eighteenth century.

Play online: https://jigex.com/HzPd

“The Koodoo” from Samuel Daniell’s African Scenery and Animals, 1804-05.

“The Koodoo” from Samuel Daniell’s African Scenery and Animals, 1804-05.

Jigsaw Puzzle

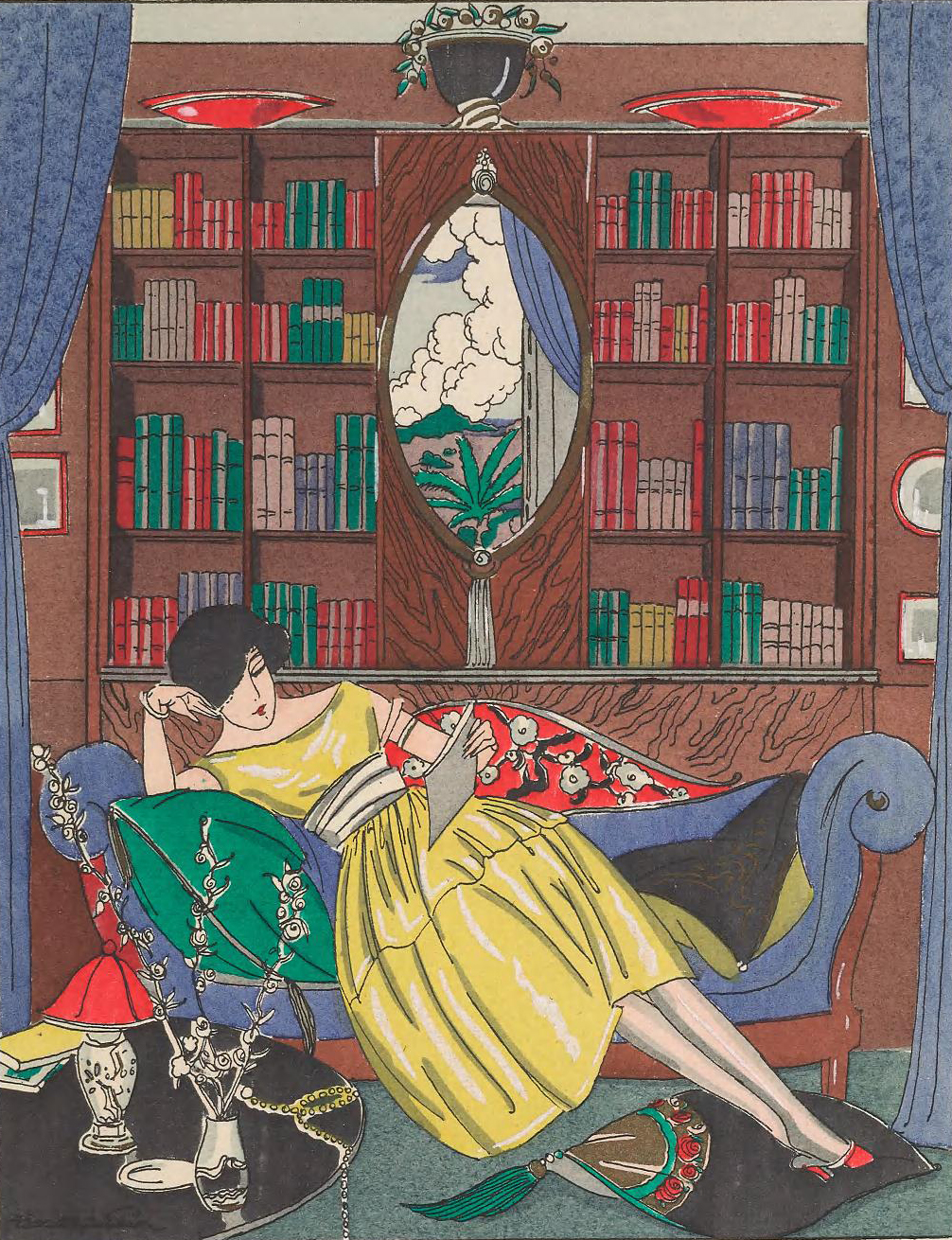

“Pour rêver un peu” from La guirlande, fasc (1919).

The title of this illustration says it all – “To dream a little”. It was published in 1919 in the French literary and art journal, La guirlande. The publication’s art director was Italian artist Umberto Brunelleschi, known for his book and fashion illustrations.

Play online: https://jigex.com/6N8V

“Pour rêver un peu” from La guirlande, fasc (1919).

“Pour rêver un peu” from La guirlande, fasc (1919).

Jigsaw Puzzle

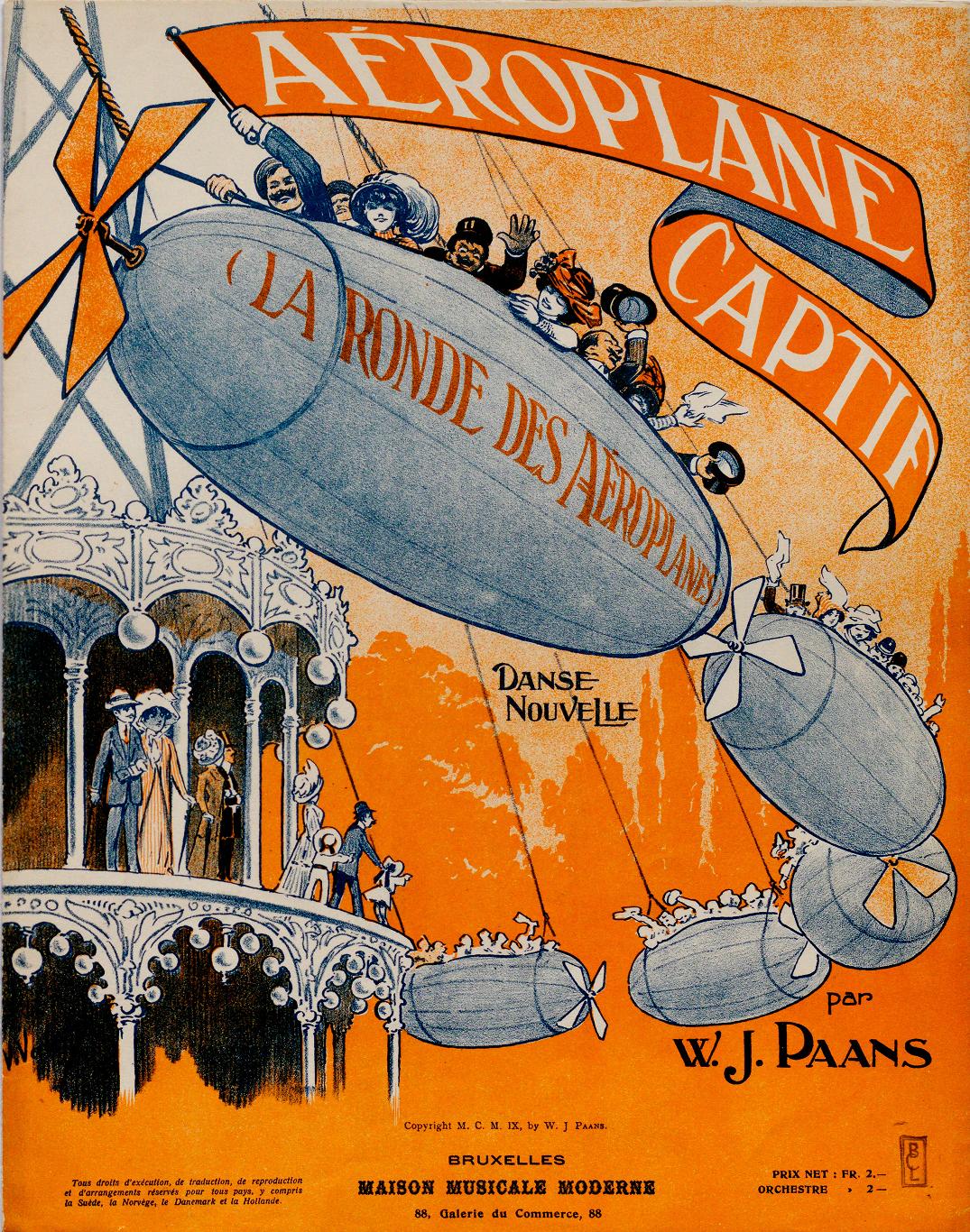

Cover from Aéroplane captif (1909).

Aéroplane captif is one of hundreds of pieces of aeronautical-themed sheet music collected by Bella C. Landauer (1874–1960). Landauer took an interest in aviation when her son became a pilot and scoured music shops to amass her collection. She’s one of many collectors featured in our exhibition, Magnificent Obessions: Why We Collect.

Play online: https://jigex.com/4E1R

Cover from Aéroplane captif (1909). Gift of Bella C. Landauer.

Cover from Aéroplane captif (1909). Gift of Bella C. Landauer.

Jigsaw Puzzle

This charming drawing of men and women strolling on the paths on the Mall in front of the Smithsonian Institution Building (The Castle) is from Robert Dale Owen’s 1849 publication, Hints on public architecture, containing, among other illustrations, views and plans of the Smithsonian institution. Owen was a Smithsonian regent and the head of the Building Committee. The exterior of the building wasn’t actually completed until 1851.

Play online: https://jigex.com/Vggy

“Smithsonian Institution, from the North East” from Robert Dale Owen’s Hints on public architecture . . . (1849).

“Smithsonian Institution, from the North East” from Robert Dale Owen’s Hints on public architecture . . . (1849).

Jigsaw Puzzle

Front cover from John Lewis Childs’ New, rare & beautiful flowers, (1890).

John Lewis Childs was born on May 13, 1856. He acquired a few acres and set up his business as a seedsman and florist at age eighteen, after one year as a florist’s helper on Long Island. His operation was based in Floral Park, New York, which was often featured in his catalogs. The Smithsonian Libraries holds more than 10,000 seed and nursery catalogs dating from 1830 to the present.

Play online: https://jigex.com/6Bzy

Front cover from John Lewis Childs’ New, rare & beautiful flowers, (1890).

Front cover from John Lewis Childs’ New, rare & beautiful flowers, (1890).

Jigsaw Puzzle

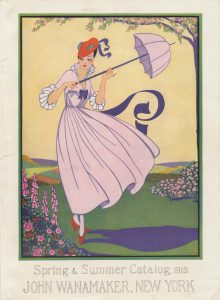

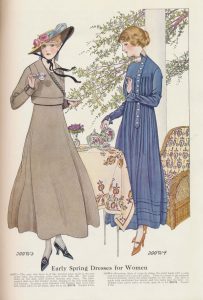

Sliding into Spring Fashion…and More in 1915

With just one glance at the front cover of this trade catalog, it appears like Spring is on the way. A lady is surrounded by flowers. Purple ribbons accessorizing her outfit are gently blowing in the breeze. Let’s take a look at what consumers might have stumbled across in 1915 while perusing this mail order/department store catalog.