Libraries' Blog

When Middle East Met West

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives exhibition, Nature of the Book, looks at the natural materials and evolving techniques in bookbinding from 1450-1850 as illustrated by our collections. As the exhibition emphasizes, the form of the European book could not have happened without the trade of natural materials to Europe from different parts of the globe – primarily Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. That trade was the direct result of the Arab conquests and cultural expansion into Central Asia and other areas. The products were exchanged through centuries of global expansion that accompanied vibrant intellectual and craft development. Ideas, aesthetic and practical, traveled along with the trade of materials that created the Islamic binding style. The effect of all this on Europe was profound, and like much else, bookbinding was transformed.

Goods such as goatskin, flax-based paper, and minerals for pigments entered Europe through Arabic trade routes. Artistic influences incorporated decorative marbled papers and gold tooling into Western binding practices.

Goods such as goatskin, flax-based paper, and minerals for pigments entered Europe through Arabic trade routes. Artistic influences incorporated decorative marbled papers and gold tooling into Western binding practices.

Early books of North and East Africa were comprised of sheets of papyrus or parchment sewn onto plain wood boards. Arabic craftspeople added leather covering to the books, often made from tanned goatskin, that completely wrapped around the boards and spine. The books often included a characteristic envelope flap used as a page marker. The Islamic book structure generally resembles a modern hardcover book, using a binding style recognizable to many today.

Goatskin cover for Qur’an, likely Syrian, later 1800’s.

Goatskin cover for Qur’an, likely Syrian, later 1800’s.

What may not be generally known is that contemporaneous to this binding style, paper became one of the most far-reaching cultural influences offered by Arab trade and expansion. Paper has been the preferred and most familiar surface for writing and printing for centuries. It could be made quickly in large quantities. Paper was light and flexible, and it easily received type setting and inks following the development of movable type in the 15th century. As a result, it eventually replaced the use of costly parchment, made from animal skins.

Modern paper can be traced to Central Asia about the 8th century, when fibers from various plants like flax and hemp were woven into linen. The textile waste was shredded, mixed with water, and beaten to make pulp. Sheets of rag paper were formed when the pulp was dried on a screen. The shredding and pulping technique moved to this area from China where, several centuries earlier, hand-made papermaking directly used the long fibers from sub-tropical plants that were similarly shredded and beaten into a pulp.

Muslim settlements in the region of Samarkand adopted this new papermaking method which spread to Iran, Turkey, India, Africa, and Europe, making the Arabic world the largest producer and trader of this versatile linen rag paper. The Italian paper mill Fabriano mastered Arabic methods of paper making learned by the Spanish, shifting the source of fine paper to a European market by the 15th century. A 600-year old volume printed on Fabriano paper is featured in the exhibition.

De re militari (1532). These illustrations are printed on Fabriano paper which is recognized for its clarity, brightness, and flexibility. The Fabriano mills date from the 13th century when Arab paper-making traditions reached Italy.

De re militari (1532). These illustrations are printed on Fabriano paper which is recognized for its clarity, brightness, and flexibility. The Fabriano mills date from the 13th century when Arab paper-making traditions reached Italy.

The paper pages in Islamic binding structures were coated with sizing using plant starches and burnished with stone pestles or glass balls leaving a shiny surface. Organic plant-based dyes were used to color the pulp. Calligraphic manuscript was used with intricately colored designs and images, using precious minerals for color and gold illumination. Gold leaf was traditionally used to embellish the pages of Islamic religious manuscripts. Qur’ans were considered prized possessions and the use of gold was a sign of their importance.

Qur ʾan (partial), Qajar-period Iran, 1800’s. Sheets of gold were used to decorate manuscript pages made of burnished paper.

Qur ʾan (partial), Qajar-period Iran, 1800’s. Sheets of gold were used to decorate manuscript pages made of burnished paper.

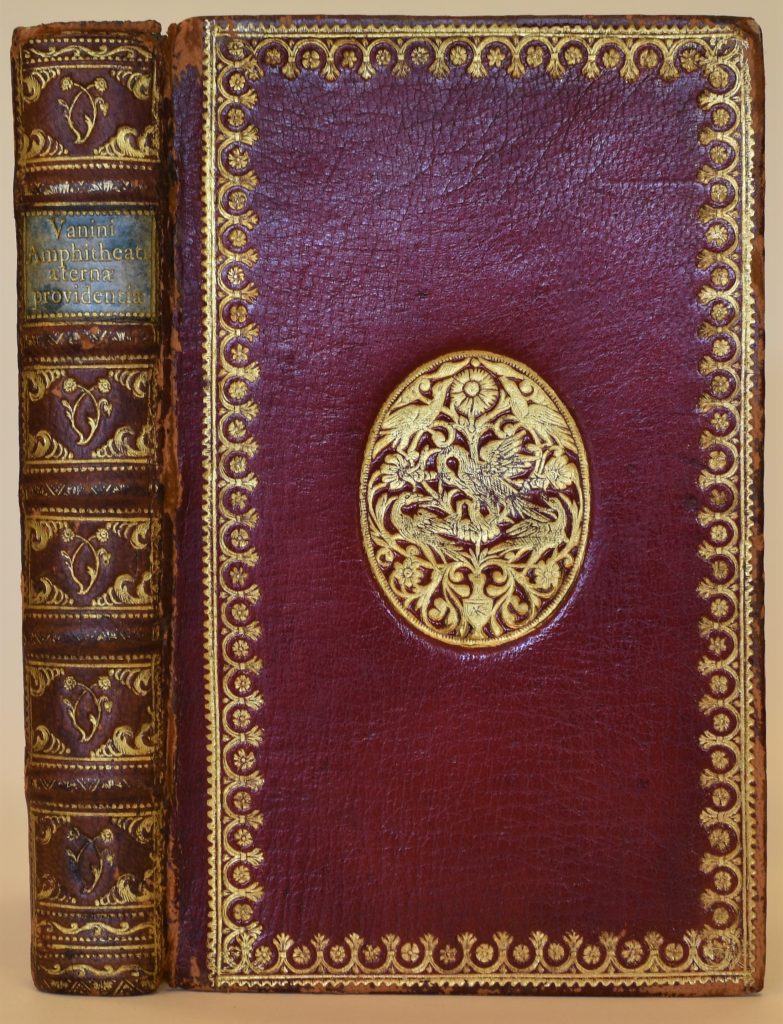

Goatskin covers dyed bright colors with ornate gold tooling and decorative colored marbled paper that was borrowed from Arabic book design, became increasingly popular by the 16th century in Europe, introduced by goods traded through Italian ports.

Amphitheatrvm æternæ (1615). Dyed goatskin and the craft of gold tooling were imported to Europe via Italian ports trading with North Africa and the Middle East.

Amphitheatrvm æternæ (1615). Dyed goatskin and the craft of gold tooling were imported to Europe via Italian ports trading with North Africa and the Middle East.

A sophisticated level of design and decoration, in addition to the use of paper, allowed Arabs to enhance the functional and artistic improvements that have had a lasting impact in the development of the book.

Through the Loupe: A Staff Profile of Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting

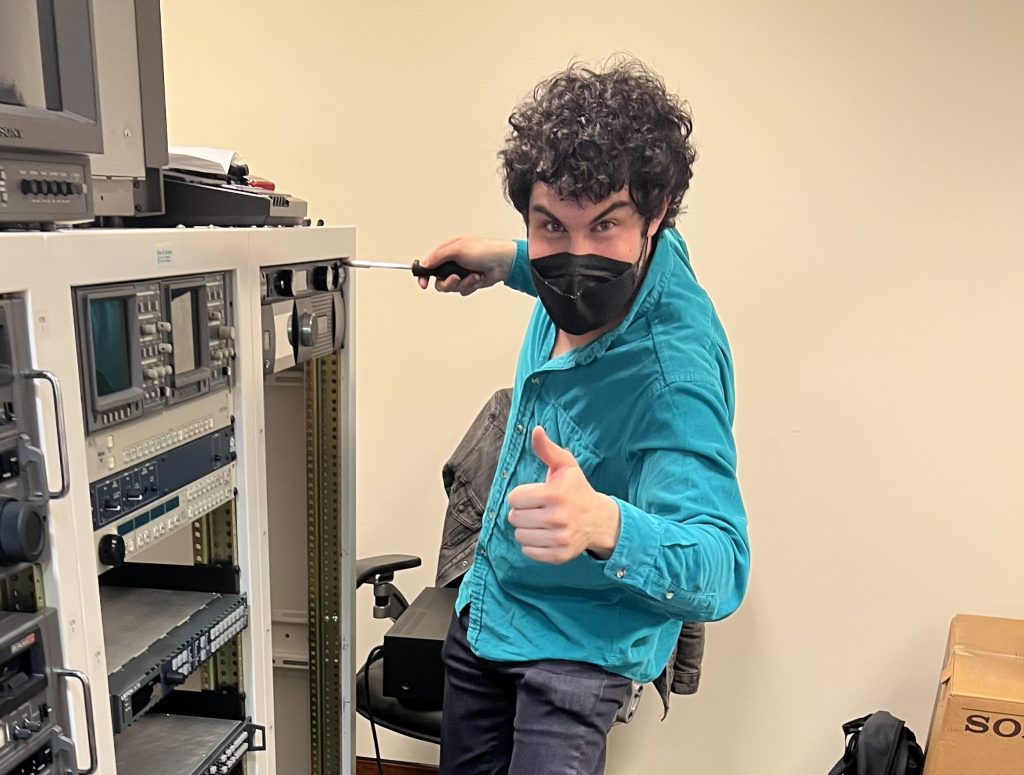

This is the third in a series of ongoing blog posts from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI), spotlighting the labor of Smithsonian media collections staff across the Institution. Analiese Oetting currently serves as Audiovisual Archives Specialist (contractor) with the National Museum of American History’s Archives Center (NMAH-AC).

Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting with the National Museum of American History’s Archives Center film collections.

Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting with the National Museum of American History’s Archives Center film collections.

Walter Forsberg: Hi Analiese, thanks for meeting today. Can you tell our Unbound readership where you’re working, today?

Analiese Oetting: Hi Walter. Yes, of course, I am in my office at ‘American History,’ which I am actually rarely in. Usually I work downstairs doing film inspection. But, we are moving spaces soon and they will be tearing down the area we’re in right now. The designer just sent tile swatch samples, and I think the renovated space will have less of a ‘dungeon vibe’ to it. [Laughs]

WF: Oh, that’s wonderful news. The basement of American History is a very historic space for film and media. If I remember correctly, that’s where the Office of Public Relations film and broadcasting section was located, beginning in 1967. There used to be a television studio there, even earlier, dating to when the building was first opened as the Museum of History and Technology in 1961…

AO: Yes, there are still several ‘Recording in Progress’ signs around, but no one’s recording much these days. It’s mainly me and the contractors installing a new fire alarm. [Laughs]

Décor in the lower levels of the National Museum of American History reveal remnants of the Smithsonian’s in-house film production past.

Décor in the lower levels of the National Museum of American History reveal remnants of the Smithsonian’s in-house film production past.

WF: Can you speak a little bit about your role in working with audiovisual collections at the Smithsonian?

AO: I am the Audiovisual Archives Specialist (contractor), which is a touch misleading given that my current job is focused solely on working with the motion picture film collections. I’ve been here on contract for the past eight months and one of my main projects is inspecting and creating an item-level inventory of all film collections at the Archives.

WF: That’s such a key and elemental thing to create when it comes to audiovisual archives.

AO: Completely. Once we created that item-level inventory, it made looking at the collections and determining priorities for digitization much easier. The project funding my job is called, “Capturing the Moment,” and is supported by the generous National Collections Program. It has a focus on home movie collections and we’re getting close to the large-scale vendor digitization phase. In the next few months, we’ll start sending films to a vendor on a rolling basis. Hollywood director George Sidney’s home movies will be among the first material, which are really interesting. Usually home movie collections are shot by amateur filmmakers, which can be their principal appeal, but these were shot by a professional filmmaker. If you’re someone interested in the ‘golden age’ of Hollywood you will find these extremely fascinating. We’re also planning to scan the home movies of composer Harry Warren, with whom I’m less familiar. We’re looking at scanning about 75,000 feet of film.

WF: Jeepers Creepers! That’s over 30 hours of material! I’m so pumped for that.

AO: Getting it all into the DAMS [Digital Asset Management System] and creating access for those films is always our obvious goal.

Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting hard at work inspecting film collections.

Audiovisual Archives Specialist Analiese Oetting hard at work inspecting film collections.

WF: While you work on all the procurement paperwork for that vendor-based scanning, I understand that you and NMAH Digital Archivist Leigh Gialanella are also digitizing some films as part of something called—correct me if I’m wrong—‘Scan Club’? Are you allowed to talk about Scan Club, or does that violate some rule of secrecy?

AO: Yes, Scan Club. I love Scan Club. It started because we needed a few things digitized for the AVMPI January Zoom with a View streamcast event. Thanks to NMAAHC’s [National Museum of African American History and Culture’s] Media Conservator Blake McDowell we were able to go next door and scan some old DuMont Television advertisements. First of all, it’s really lovely to be able to scan film in-house because of the slowness associated with federal procurement contracting with a vendor. With Scan Club we’re able to show up, scan film, get some stuff back immediately, and feel like we’re actually digitizing collections—all within the same day. It’s also incredible to get out of the museum basement, visit colleagues at another unit, and open dialogue. ‘What are you working on?’ ‘How do you do that?’ Meeting new people and faces— The fellowship of comparing notes in-person about projects is really nice, especially after the pandemic.

WF: Wow! I know that striving to be ‘Nimble’ is a key focus of Smithsonian Secretary Bunch’s five-year “Our Shared Future” strategic plan, and same-day film scanning sure sounds like it fits the bill! Can you talk about some of the recent films you’ve scanned?

AO: Last week, we scanned 16mm television kinescope film recordings from the Hills Bros. Collection. It is an interesting collection, and has a little bit of everything—home movies, baseball games, factory footage, promotional films, and even a few reels from a television program called, Shirley Temple’s Storybook from 1958. Hills Bros. coffee was a sponsor of many TV shows and the collection represents the breadth of materials you find in Archives Center.

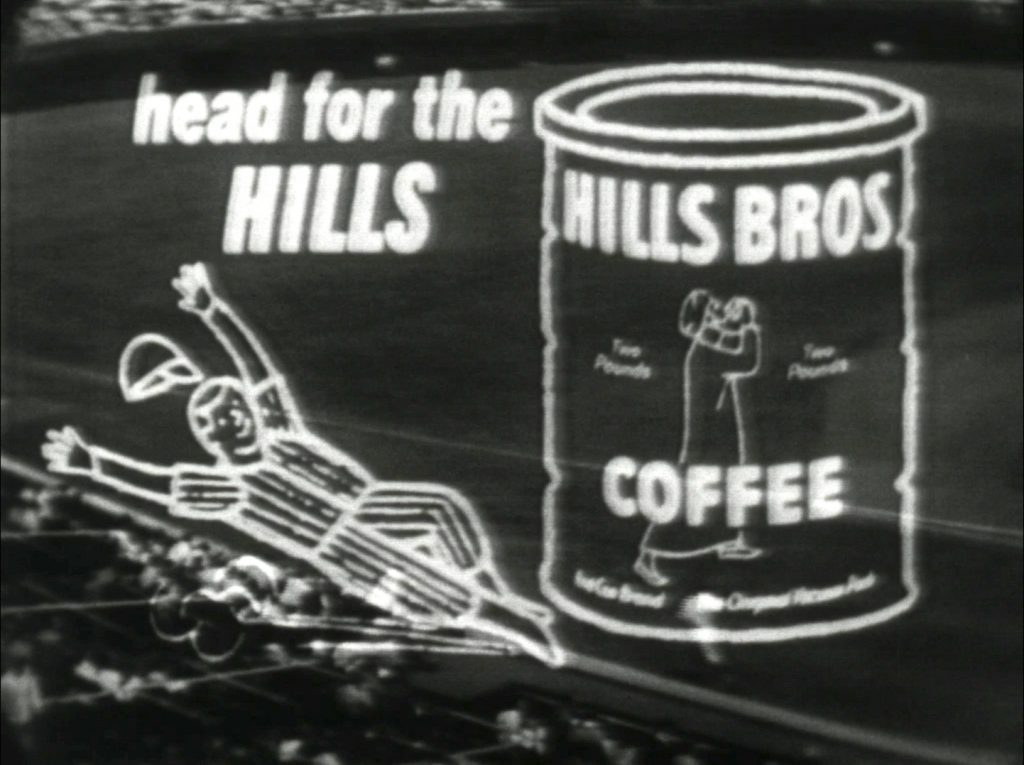

Advert sponsoring pre-game program, Lead Off Man with Vince Lloyd, broadcast May 13, 1962 live from Wrigley Field on WGN-TV. Collection item # Reel OF 395.13, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Advert sponsoring pre-game program, Lead Off Man with Vince Lloyd, broadcast May 13, 1962 live from Wrigley Field on WGN-TV. Collection item # Reel OF 395.13, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

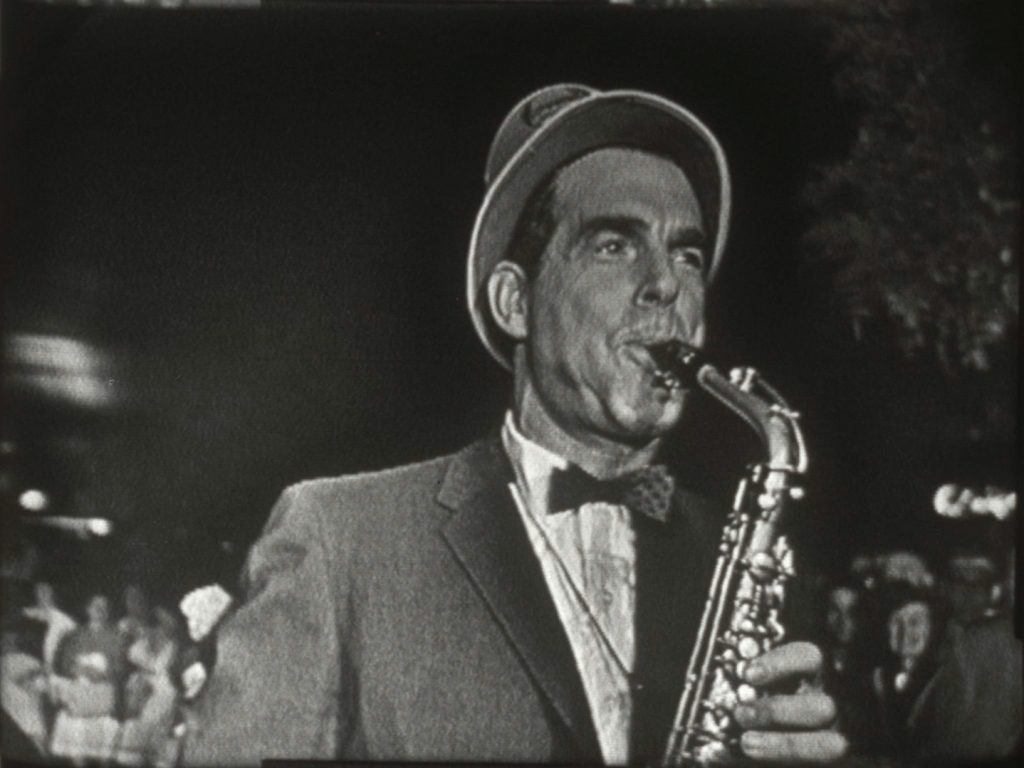

WF: I was researching about the Hills Bros.-sponsored 1962 TV program, Meet Me at Disneyland, and it appears that yours might be the only-known copy in existence. While the show was a little underwhelming and heavy on the Dixieland, the sequence of Fred MacMurray playing saxophone was satisfyingly curious.

AO: It’s always cool to know you have something unique. It’s always interesting to see what might pop up in a collection because even if you’re not necessarily interested in Hills Bros. Coffee. Having these little appearances by public figures like Walt Disney and Fred MacMurray that haven’t been widely seen by a modern audience is nice to have and fun to share!

End credit title card from the 1962 KTTV television program, Meet Me at Disneyland, broadcast June 9, 1962. Collection item # Reel OF 395.12, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

End credit title card from the 1962 KTTV television program, Meet Me at Disneyland, broadcast June 9, 1962. Collection item # Reel OF 395.12, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Actor Fred MacMurray plays saxophone on the 1962 KTTV television program, Meet Me at Disneyland, broadcast June 9, 1962. Collection item # Reel OF 395.12, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Actor Fred MacMurray plays saxophone on the 1962 KTTV television program, Meet Me at Disneyland, broadcast June 9, 1962. Collection item # Reel OF 395.12, Hills Bros. Coffee Company, Incorporated Records, 1856-1989, undated, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

WF: Can you speak about how you got interested in audiovisual archiving, and what your career trajectory has been?

AO: I was always super interested in film, and took film studies courses at York University during my undergrad. Like many fresh-faced 18 years olds in film school I thought I wanted to be a filmmaker. But, eventually it became clear at a certain point that I didn’t want to be a filmmaker, and I wasn’t super interested in academia or pursuing a PhD in cinema studies. I came across this program at Ryerson University—now, called Toronto Metropolitan University—for ‘Film Preservation and Collections Management’ and thought: this sounds cool as hell. I applied and got in, and when I got there everything really clicked into place. I was, like: ‘This is it!’ The program is very committed to providing internships and residency training.

WF: What were some of your practicuum experiences like?

AO: I did my internship at the Art Gallery of Ontario, working with a film collection they have from the 1960s and 70s of works by Canadian filmmakers—David Rimmer, Michael Snow, Joyce Wieland. There was a lot of time on the film bench, assessing condition and performing inspection. It was really nice to get that hands-on film handling experience. Then, I spent six months for my residency at the Vancouver Cinematheque in their film archive. The people there are lovely, they do great programming, and I undertook a lot of detective work about who donated specific films and updating their film database. That was also a reality check for me because it was messy—films don’t always show up, beautifully wound onto cores and in good condition.

WF: Did you have other archival jobs before arriving at the Smithsonian?

AO: In 2019 I got a job at the Sundance Institute straight out of grad school, working in their archives as a Digital Assets Assistant. That really blew my mind, and the job involved processing born-digital photos of current year-round events and programs and then also working on getting some of the older scanned materials into the DAMs. For a lot of that older stuff there’s no metadata, so most of that job is detective work, looking at past festival photos and figuring out: ‘Who’s that?’ ‘What film premiere was this?’ I really love that kind of work. In addition to festival materials, the Institute has saved a lot of documentation of their lab programs back to 1981.

WF: What are you working on next at the Archives Center?

AO: Day-to-day I’m always working on processing film collections, creating and updating finding aids for the the materials, working with interns to get things rehoused and also starting to document workflows and processes as I go along to sort of keep things consistent moving forward. We’re obviously very focused on our home movie preservation project at the moment, but always trying to identify other materials that need preservation, how best to get it done and how to make it accessible.

Three New Members Join Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board

The Smithsonian Institution’s Board of Regents recently appointed Evelyn Dilsaver, Cathy Heron and David H. Lipsey to the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board. They join 17 prominent community and business leaders dedicated to building the Libraries and Archives’ collections, increasing digital initiatives, advancing education, progressing library and archival preservation, creating high-quality exhibitions and programs, and securing a financial legacy.

“I am excited to welcome three distinguished new members to our Advisory Board,” said Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, director, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. “They each will bring diverse expertise and strengths to our work, furthering the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ important mission and reach with local and global audiences alike.”

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Advisory Board consists of members from across the United States. The mission of the board is to help the organization to provide authoritative information, steward the Smithsonian’s institutional memory and create innovative services and programs for Smithsonian researchers, scholars, scientists, curators, archivists, historians and other staff, as well as the public at large.

A CPA at Ernst, Evelyn spent the first 17 years of her career in the audit and finance function as Controller for a bank and for Charles Schwab and as CFO and Chief Administrative Officer for U.S. Trust, a wealth management firm. She was given the opportunity to hone her skills in marketing, business development, strategy, M&A and product development, culminating in the role of EVP of Charles Schwab, member of the Management Committee and President and CEO of Charles Schwab Investment Management.

Evelyn is a recognized leader in building motivated teams in the public and non-profit worlds. As President and CEO of Charles Schwab Investment Management she was responsible for all aspects of the business, growing the assets to over $200 billion while generating $1 billion in revenue.

Recognized in the community for her leadership, she has received San Francisco Business Times “100 Most Influential Woman” award, 2003-2009; CSU 2008 East Bay Alumnae of the year; 2014 “Outstanding Director;” and in 2018, Most Inspired Award by the SF Business Times. In 2016, she received an Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from Cal State University East Bay, NASDAQ 100 Directors in 2019 and a NACD directorship 100 Honoree for 2020. She is also a frequent guest speaker and panelist on board of director topics at NACD Global and Chapter events, Women Corporate Director events and on-boarding boot camps for aspiring directors. She also speaks on leadership skills at Employee Resource Groups and University MBA programs and as a moderator for programs at The Commonwealth Club.

Evelyn has served on several public and private boards and currently serves on public company boards for Tempur Sealy (TPX), Health Equity (HQY) and Quidel/Ortho (QDEL); global consulting firm Protiviti and Bailard REIT; and leadership roles in several non-profit boards, including as former Chair of The Commonwealth Club and of the Blue Shield Foundation, and Co-Chair of Women Corporate Directors Advisory Board. She formerly served on the boards of Blue Shield of California, Long Drugs, Tamalpais Bancorp, Aeropostale, High Mark Funds and the National Association of Corporate Directors NorCal chapter. She is a graduate of CSU East Bay and the Stanford Senior Executive Program.

Cathy is a retired attorney with more than 40 years of experience in the investment management, tax and retirement regulatory fields. At the Capital Group Companies, one of the 10 largest investment management firms in the world, she served as General Counsel to Capital Bank and Trust, a trust bank for retirement assets and high net-worth individuals, and as a Senior Vice-President of the Fund Business Management Group of Capital Research and Management Company, the investment adviser to the American Funds. She was a founding member of the groups that established the largest 529 college savings plan in the nation and the American Funds industry-leading target date retirement funds. She also served as chair of Capital Group’s Retirement Plan Committee, responsible for administering plans covering more than 7,000 employees.

Prior to working at the Capital Group, Cathy was Senior Vice-President for Tax, Pension and International issues at the Investment Company Institute, the trade association for the US mutual fund industry. While living in Washington, she also worked in the Washington office of a major New York law firm, the national tax office of one of the largest international accounting firms and at the US Department of Labor, where she served as Special Assistant to the Solicitor of Labor.

Cathy earned her Bachelor of Arts degree from Wellesley College, her J.D. from Boston University School of Law and an LLM in taxation from Georgetown University Law School.

Cathy and her husband, Al Schneider, divide their time between homes in Manhattan Beach, Calif. and Arlington, Va.

David H. Lipsey is a principal consultant and advisor working internationally on creating value from organizations’ digital assets – and setting in place the organizational and strategic processes to achieve success with this. David has been involved with the field of digital asset management (DAM) since its inception in 1998 and is a global leader in the field.

David’s work in DAM informs a deep experience in a diversity of both public and private sectors as well as content “types” – print, images, graphics, audio, video, CAD, aesthetic, medical, and software (gaming/VR/AR/data) assets. He is well known as a leader in setting the ever-changing context for how “digital” goes to work – and works in service of mission.

His work in the non-profit world includes the Library of Congress’s foundational National Digital Library, The Getty, The National Gallery of Art, The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Sesame Workshop, The Ringling Museum, The PBS NewsHour, The National Board of Medical Examiners, WGBH (Boston), WNET (New York City) and many others.

His particular focus on digital content includes extensive work with insights gleaned from private sector experience with companies as diverse as General Motors, Hasbro, Lands’ End, HBO, Disney, PVH, Sony Music, Feld Entertainment, Garmin, A+E, Penguin Random House, The New York Times, Pearson and dozens more help to inform the meanings and value of DAM.

Previously, along with founding senior consulting roles, David served as Industry Principal for Media & Entertainment for SAP and was, prior to that, a Co-Founder of one of the first and still-leading providers of enterprise DAM software.

He serves as the Global Chair of the international DAM Conferences known as “The Art and Practice of Managing Digital Media”, including the global (virtual) conferences on DAM for Museums, attended in the past three years by more than 6,000 Museum, Library, Archive and Performing Arts professionals from 75 countries; he is a principal co-author of the widely used Digital Asset Management Capability Model, and a sought-after speaker in DAM. David co-founded the Rutgers University Professional Certificate in Digital Asset Management and is the Academic co-Director and an instructor. David was named the Rutgers University School of Communication & Information Sciences Instructor of the Year in May 2021. He is a frequent guest lecturer at numerous universities about DAM and is a co-founder of Toronto Metropolitan University’s Lab for Excellence in DAM.

David is a graduate of Phillips Academy (Andover, Mass.) and New College (Sarasota, Fla.). He resides in McLean, Va.

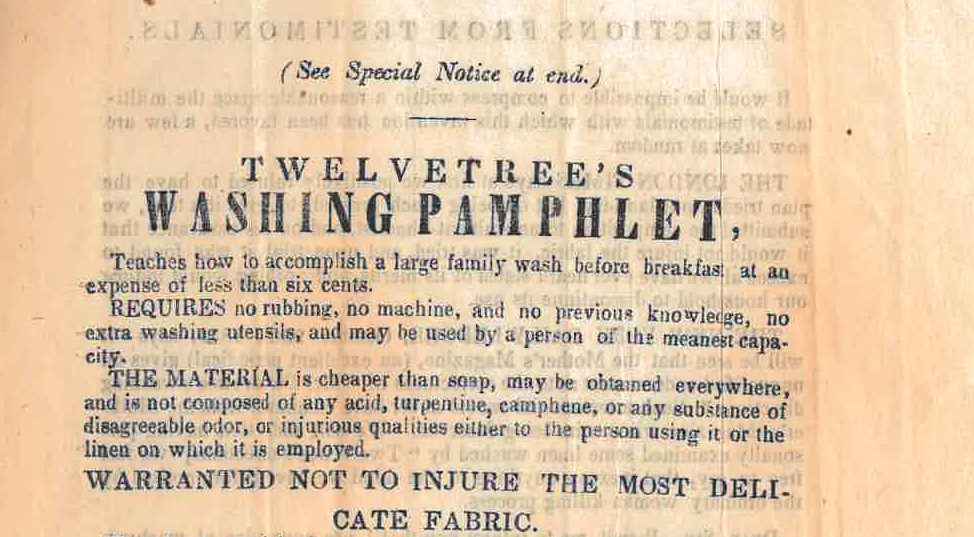

How To Take a Product Line on the Road

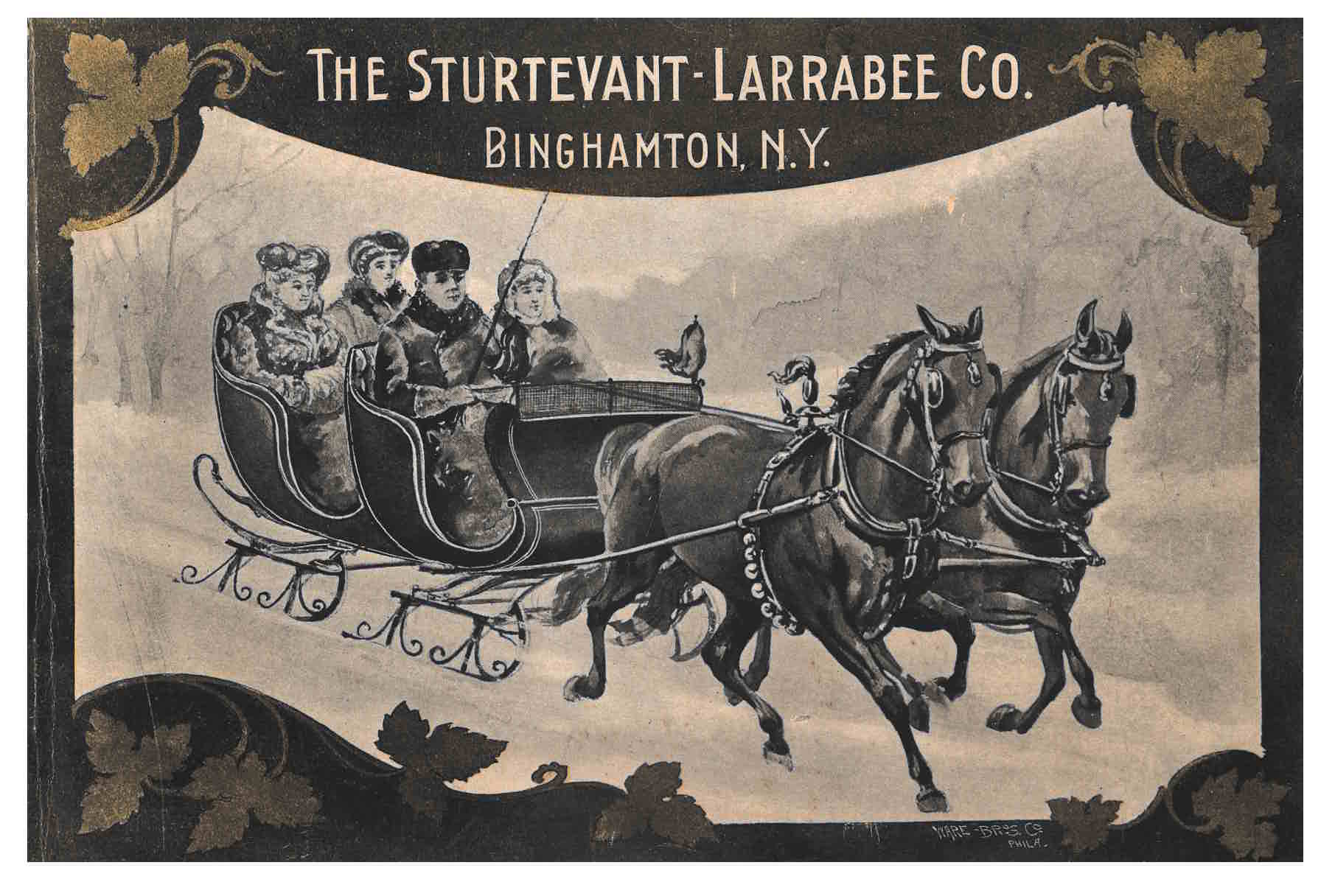

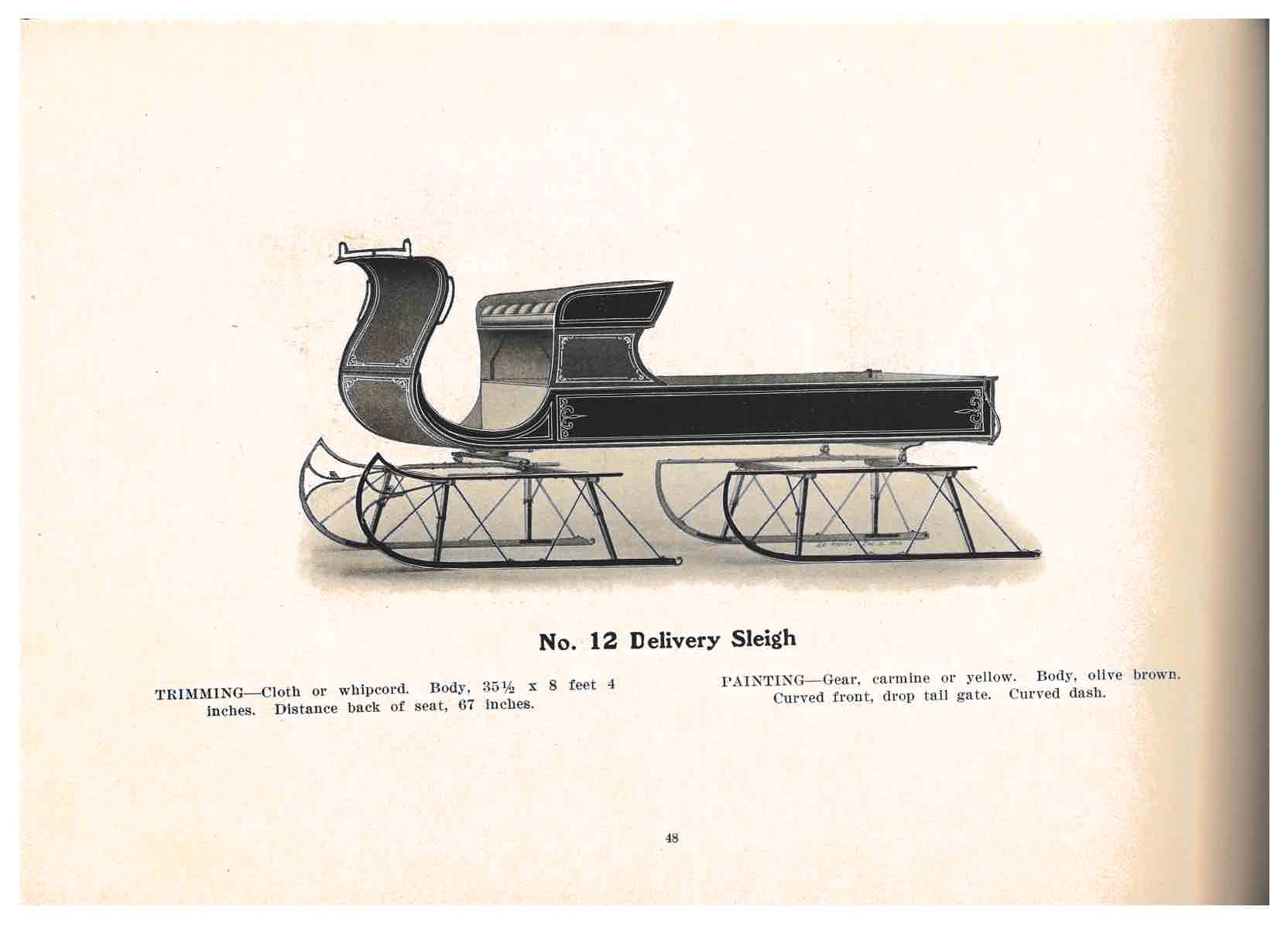

In the early 20th Century, a knock on the door might have come from a salesperson offering the latest in cosmetics or household supplies. How did salespeople at that time display their product line? What kind of vehicle did they use? A circa 1919 J. R. Watkins Co. trade catalog offers a few ideas.

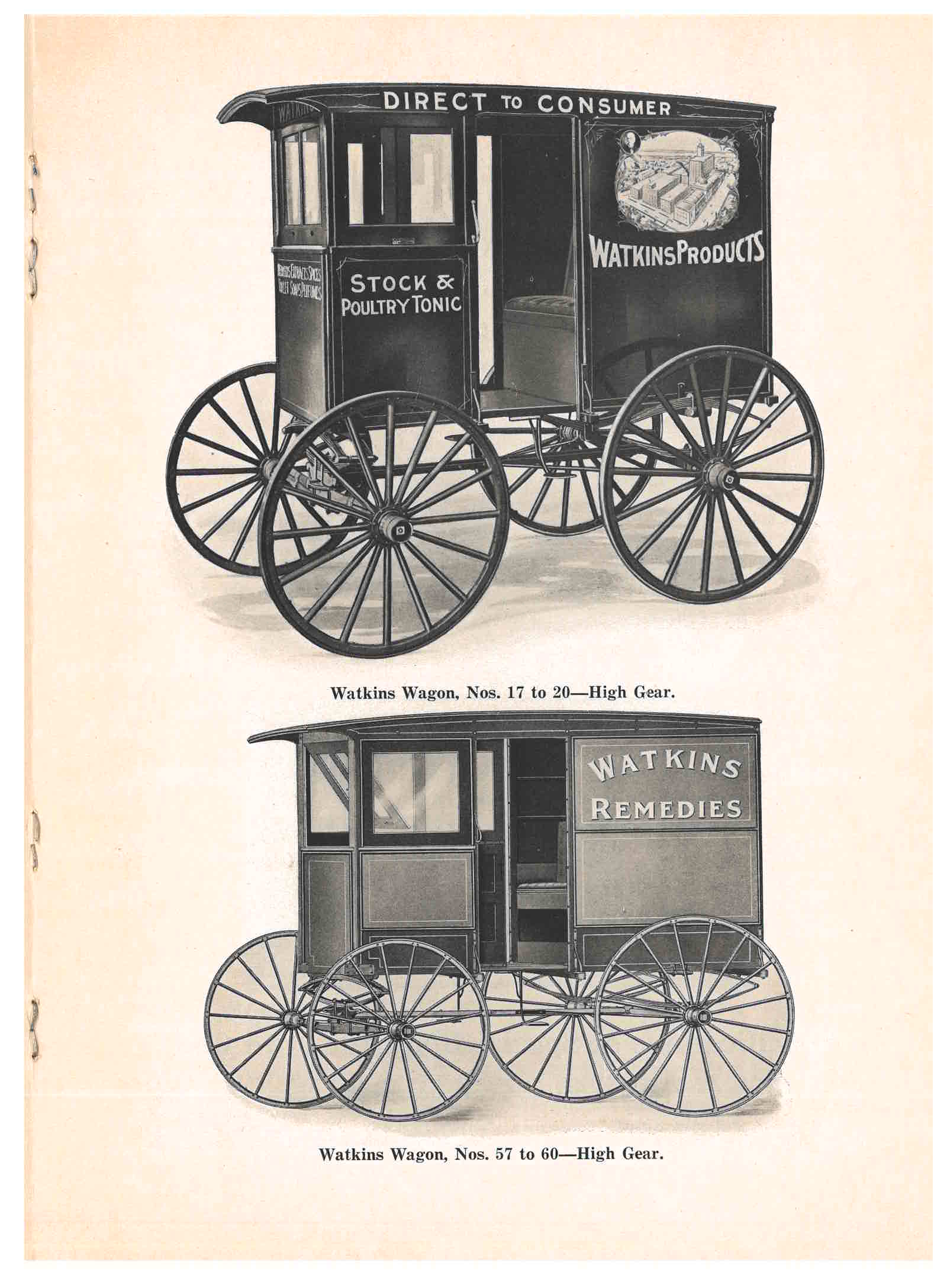

The trade catalog is titled Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919) by J. R. Watkins Co. As might be guessed from the catalog title, it mainly illustrates wagons. However, it also includes product sample cases for Watkins salesmen to carry when visiting customers.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), front cover, company administration building.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), front cover, company administration building.

As the catalog points out, first impressions can make a difference. It explains, “The man who is bright and neat and who drives up with a lively team and a handsome Watkins wagon finds his battle half won.” For that reason, J. R. Watkins Co. offered their salesmen specific types of wagons which were lettered with the Watkins name, salesman’s name, and types of products sold, such as extracts, spices, perfumes, etc. This was a form of advertising, and as the catalog further emphasizes, a Watkins wagon “will quickly pay for itself.”

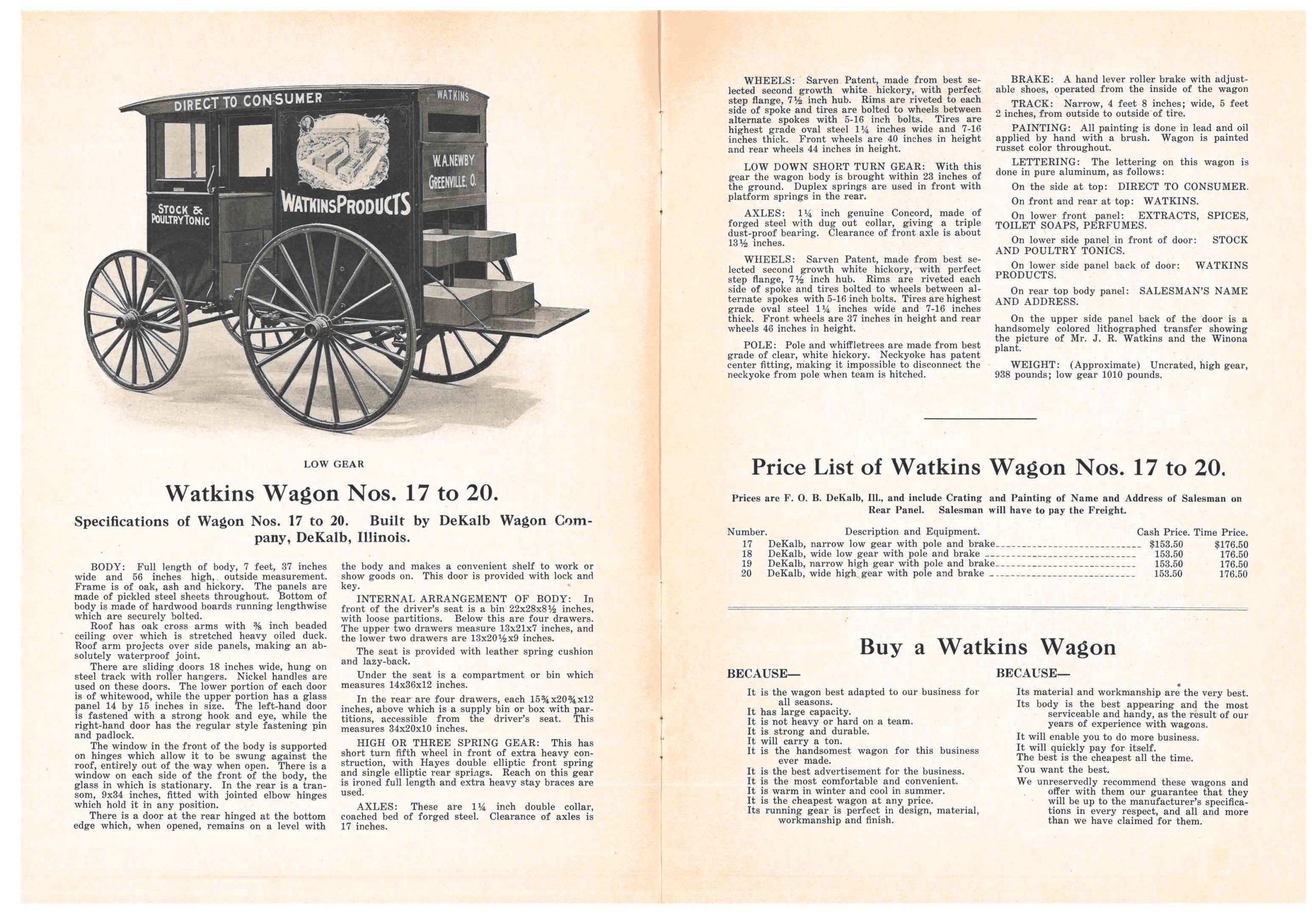

The Watkins wagons were built by DeKalb Wagon Co. of DeKalb, Illinois. These wagons were ordered by J. R. Watkins Co. in large quantities and then sold to the Watkins salesmen. In the catalog, J. R. Watkins Co. explains that they sold the “wagon for cash at about what it costs us ordering in large quantities.”

For salesmen who preferred not to pay by cash, another option was offered at a higher cost. This was to buy it “on time” and charge it to their account along with goods ordered. In this situation, the salesman’s sureties were also required to sign the order.

What were the benefits of buying a Watkins wagon? For one thing, these wagons provided a convenient option for displaying products. A handy shelf was created by simply opening the rear door. The hinges of the rear door were at the bottom, allowing it to open out and making it level with the bottom of the body of the wagon. This created a shelf, or display area, for showing products to customers. The wagon illustrated below, labeled as Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20, shows the shelf created from the rear door. For security purposes, the door had a lock and key.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered pages [4-5], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20 and reasons to buy a Watkins Wagon.Besides a place to display product samples when visiting customers, the shelf might also have been used as a workspace for organizing products in the wagon’s storage compartments, bins, and drawers.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered pages [4-5], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20 and reasons to buy a Watkins Wagon.Besides a place to display product samples when visiting customers, the shelf might also have been used as a workspace for organizing products in the wagon’s storage compartments, bins, and drawers.

As shown in the illustration below, four drawers were located above the rear door/pull-out shelf. Above those drawers, there was a supply bin. It was accessible from the driver’s seat. Another compartment or bin was located under the driver’s seat while four additional drawers and a bin were situated in front of the driver’s seat.

The catalog mentions the Watkins wagon will “quickly pay for itself.” How was that possible? Perhaps by using the wagon itself as a means for advertising. This was accomplished through custom lettering on the exterior of the wagon.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [4], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20.The wagon drew attention to the Watkins name in various ways. As shown in the above illustration, the company name “WATKINS” was painted towards the top of the rear of the wagon. It was also painted on the front of the wagon. A colored lithographed transfer was placed on the side of the wagon with a picture of Mr. J. R. Watkins, the founder of the company, along with an image of the company’s plant buildings in Winona, Minnesota.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [4], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20.The wagon drew attention to the Watkins name in various ways. As shown in the above illustration, the company name “WATKINS” was painted towards the top of the rear of the wagon. It was also painted on the front of the wagon. A colored lithographed transfer was placed on the side of the wagon with a picture of Mr. J. R. Watkins, the founder of the company, along with an image of the company’s plant buildings in Winona, Minnesota.

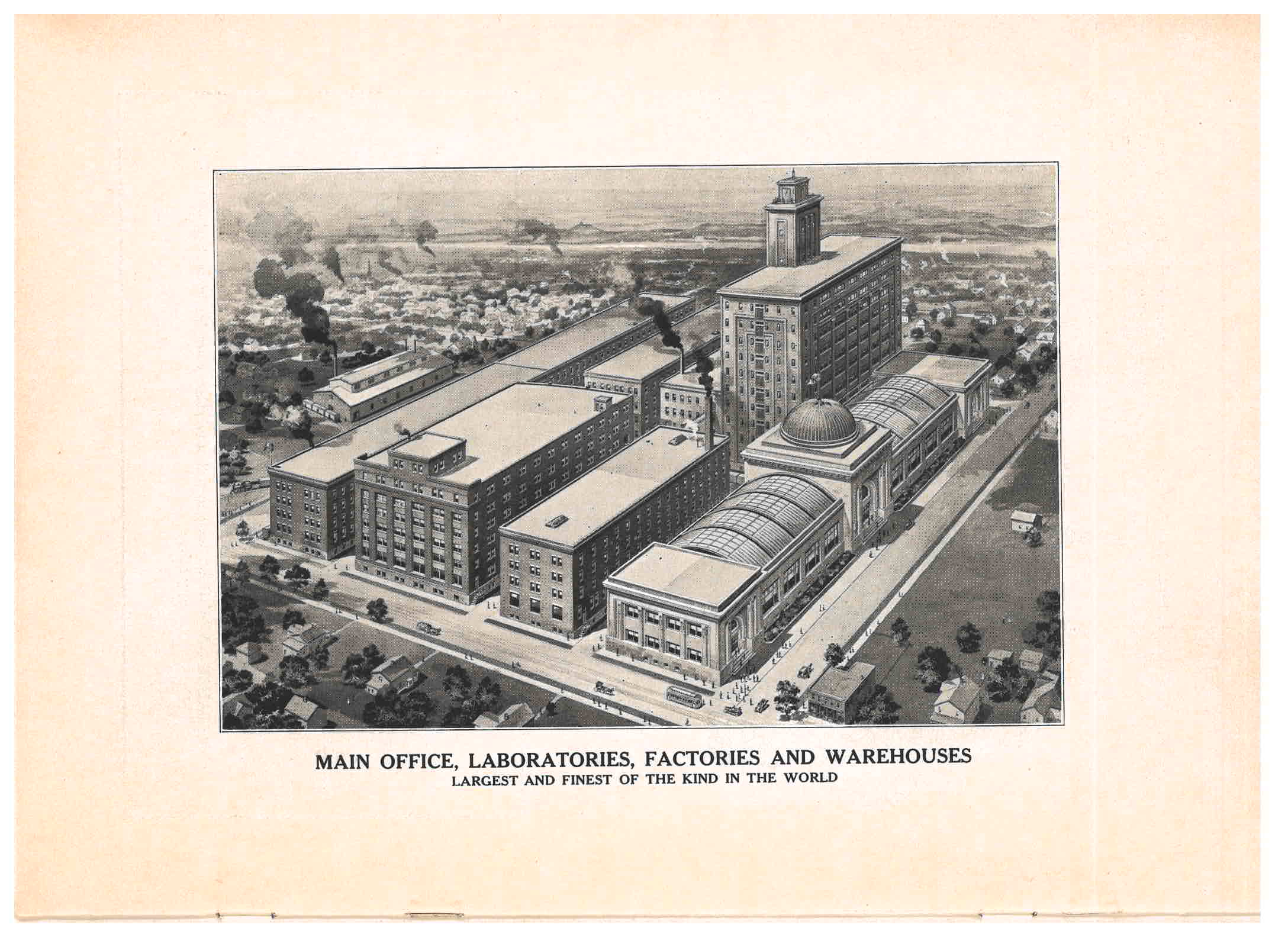

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [12], company’s main office, laboratories, factories, and warehouses.To further emphasize the company name, “WATKINS PRODUCTS” was lettered beneath the image of the company buildings. The name of the salesman and his address, such as city and state, were painted on the rear of the wagon above the door. Advertising the company’s ability to sell directly to customers, the wagon included lettering on the side near the top which read “DIRECT TO CONSUMER.”

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [12], company’s main office, laboratories, factories, and warehouses.To further emphasize the company name, “WATKINS PRODUCTS” was lettered beneath the image of the company buildings. The name of the salesman and his address, such as city and state, were painted on the rear of the wagon above the door. Advertising the company’s ability to sell directly to customers, the wagon included lettering on the side near the top which read “DIRECT TO CONSUMER.”

The wagon also advertised the variety of Watkins products sold by their salesmen. Painted on the wagon’s lower front panel were the words, “EXTRACTS, SPICES, TOILET SOAPS, PERFUMES” while “STOCK & POULTRY TONIC” was painted on the lower side panel by the door. The Watkins wagon below (bottom), labeled as Watkins Wagon, Nos. 57 to 60, is lettered with “WATKINS REMEDIES” on its side. Overall, the wagon was painted in russet, a reddish-brown color.

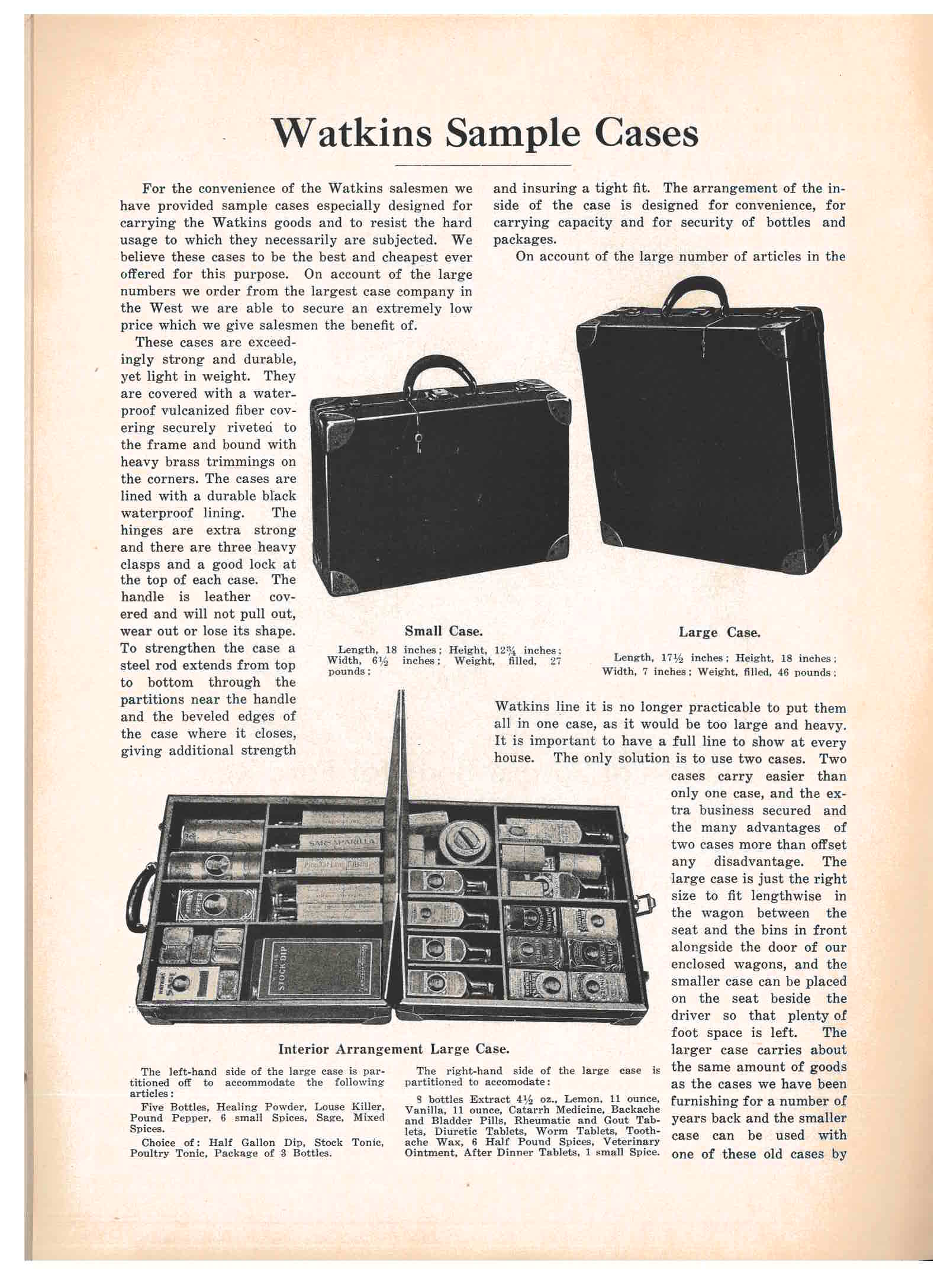

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [7], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20 high gear and Watkins Wagon Nos. 57 to 60 high gear.What happened when a Watkins salesman arrived at a customer’s home? How did he present items for sale? Perhaps he set them out on the rear wagon door/shelf or maybe he used a Watkins Sample Case. Sample cases provided a way to carry products to customers in a neat and organized manner. J. R. Watkins Co. offered two sizes, a small and large case. The small case measured 18 inches long, 12 ¾ inches high, and 6 ½ inches wide while dimensions for the large case were 17 ½ inches long, 18 inches high, and 7 inches wide. When filled, the large case weighed 46 pounds and the small case weighed 27 pounds.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [7], Watkins Wagon Nos. 17 to 20 high gear and Watkins Wagon Nos. 57 to 60 high gear.What happened when a Watkins salesman arrived at a customer’s home? How did he present items for sale? Perhaps he set them out on the rear wagon door/shelf or maybe he used a Watkins Sample Case. Sample cases provided a way to carry products to customers in a neat and organized manner. J. R. Watkins Co. offered two sizes, a small and large case. The small case measured 18 inches long, 12 ¾ inches high, and 6 ½ inches wide while dimensions for the large case were 17 ½ inches long, 18 inches high, and 7 inches wide. When filled, the large case weighed 46 pounds and the small case weighed 27 pounds.

Its exterior was covered with a waterproof vulcanized fiber trimmed with brass on each corner while the interior was fitted with black waterproof lining. The cases had a leather covered handle, three clasps to open and close, and a lock.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [10], Watkins small and large sample cases (closed views) and large sample case (filled open view).For extra strength, each case was fitted with a steel rod extending “from top to bottom through the partitions near the handle and the beveled edges of the case where it closes.” The interior of each case included partitions to securely store products of varying sizes, though, as shown below, the right side of the small case did not have partitions.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [10], Watkins small and large sample cases (closed views) and large sample case (filled open view).For extra strength, each case was fitted with a steel rod extending “from top to bottom through the partitions near the handle and the beveled edges of the case where it closes.” The interior of each case included partitions to securely store products of varying sizes, though, as shown below, the right side of the small case did not have partitions.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [11], Watkins small sample case (filled open view).J. R. Watkins Co. recommended both the large and small cases to their salesmen because one case did not fit everything. The catalog even suggests locations in the wagon to stow these cases. The large case fit in the front of the wagon between the seat and front bins along the door lengthwise while the small case could be placed on the seat next to the driver. This provided ample foot space for the salesman.

J. R. Watkins Co., Winona, MN. Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919), unnumbered page [11], Watkins small sample case (filled open view).J. R. Watkins Co. recommended both the large and small cases to their salesmen because one case did not fit everything. The catalog even suggests locations in the wagon to stow these cases. The large case fit in the front of the wagon between the seat and front bins along the door lengthwise while the small case could be placed on the seat next to the driver. This provided ample foot space for the salesman.

Catalogue and Price List of Wagons (circa 1919) by J. R. Watkins Co. and other trade catalogs by J. R. Watkins Medical Co. are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

AVMPI: Building Upon a Sound Foundation

It’s an enormous opportunity and a personal thrill to join the pan-Institutional Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI). I’m excited to explore and work with some of the collections our team will digitize, preserve, and help to make accessible. As the Audio Preservation Specialist for AVMPI, I’m eager to ensure audio collections held here at Smithsonian Libraries and Archives – and across the broader Smithsonian – will be available in the future, as the initiative moves forward and fulfills its goals.

My interests in recorded sound preservation stem from my background as an audio engineer and musician, working in record stores, radio, live sound, and recording my friends and community. Socializing with “sound people” and learning about their interests has always been one of the most enjoyable elements of working in the audio world. In my travels, work, and crate-digging adventures, I’ve realized that so much of our recorded sound heritage has an incredible story to tell. In many cases, the most fascinating material never resurfaced beyond its original release format, did not get the full-scale production it deserved, or was on entirely non-commercial media in an archive. Preservation work felt like a great way to combine my audio engineering skill set with my interest in preserving these stories.

I arrive at the Smithsonian with some experience under my belt at other cultural heritage institutions, a digitization vendor, and academic libraries. My beginning as a career preservationist happened to start toward the beginning of recorded sound itself. I handled audio materials working as a volunteer at the Thomas Edison National Historical Park audio archive, which was close to my childhood home in New Jersey. Through digitization, some cataloging, and watching curator Gerald Fabris work, I had my first glimpse into what it looked like to meet best practices and keep things organized. From there, I was hired at a preservation vendor that was facilitating bulk digitization for Edison materials. I led the quality control team and learned about more complex workflow development and iteration. Acting as the final checkpoint for many incredible projects, including some Smithsonian work, I learned about metadata and transfer errors. After my time at the vendor, I moved to the University of North Carolina to perform audio preservation and reformatting under the leadership of the top-notch team at the Southern Folklife Collection. While at UNC, I obtained an Information Science master’s degree, which bolstered my understanding of many of the more formal information processes that happen in a large organization. I had a wonderful time working last summer as a Junior Fellow at the Library of Congress working with Kate Murray on the Sustainability of Digital Formats website — this provided some fantastic insight into practical elements of digital preservation and file format structure. Prior to arriving at the Smithsonian, I was in Columbus, Ohio, leading the beginning stages of The Ohio State University’s audiovisual digitization and preservation program.

Reconfiguring the audio setup at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center. Photo: Siobhan Hagan

Reconfiguring the audio setup at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center. Photo: Siobhan Hagan

In my new role as Audio Preservation Specialist, I’m tasked with handling and facilitating the stabilization and preservation reformatting of many pieces of material — tapes, cartridges, discs, cylinders, belts, and more. I’ll also develop and undertake quality control for our audio digitization processes. AVMPI’s goal of serving as a centralized resource means that some of my first priorities are to shape unified standards and workflows, such as file embedded metadata and tape baking and cleaning. I have also been evaluating much of our audio equipment and performing minor repairs to ensure AVMPI obtains quality reformatting results. I hope to serve as an advocate throughout the Institution for its audio collections, building upon the great work already happening at Smithsonian in this domain, with many of our Task Force members providing helpful advice and context. Collaboration across the Institution with Smithsonian staff across AVMPI’s various labs and priorities will be a key part of supporting the Initiative.

I have encountered many moments that resonate personally with why I (and, I’d imagine, many of us) make careers out of preservation: recordings of people who may have known relatives of mine; rare documentation of important historical events; incredible multitrack recordings and demos of some of my favorite music; fascinating technological experimentations in the concept of taking moving air particles and wrangling them into some other domain — whether it be grooves, tiny magnetic specks, or light.

Ensuring one of our Tascam compact cassette decks is ready for preservation use. Photo: David Walker

Ensuring one of our Tascam compact cassette decks is ready for preservation use. Photo: David Walker

One of my strongest passions in this field is extending our preservation practices into the technical information necessary to perform this work. Ensuring the longevity of specialized knowledge surrounding the unsupported legacy equipment we use to migrate our audiovisual cultural heritage is an urgent need. As a “digital native” who came of age in an era of less mechanical parts and more microscopic, surface-mount components, I am grateful to mentors and engineers who are willing to pass on important skills. Much of this is facilitated through several organizations full of wonderful people, such as the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, the Audio Engineering Society, and the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives. However, as folks retire and this information leaves the field, it is becoming apparent that we need to actively collect technological information and make it accessible in innovative ways to combat “degralescence.” This is important, especially so that those without the resources of major institutions can retrieve information from obsolete carriers at high quality. Skill-sharing, organization of information, and documentation are crucial to this, and I hope to make such tasks part of my work here at the Smithsonian.

I look forward to sharing some wonderful digitized material, fun technical challenges, and more from AVMPI in future blog posts!

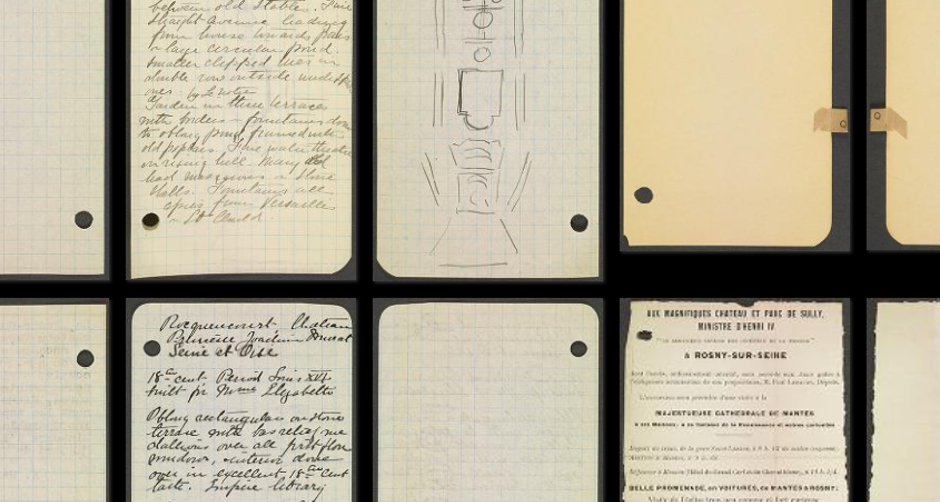

The ABCs of the Corcoran Artist Files: the Ls

In the series called “The ABCs of the Corcoran Artist Files” the American Art and Portrait Gallery (AA/PG) Library will explore artists through the materials from the recent Corcoran Vertical File Collection donation by featuring artists whose surnames begin with that letter. This time we are looking at the artists whose last names start with L. This exhibition and blog post were curated and written by Emily Moore, the Instruction and Outreach Archivist at the University of Oregon, who was a 2019 summer intern at the AAPG Library. After a pandemic pause, materials are once again on display in the library.

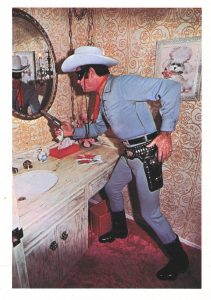

The discovery of a vertical file collection is an act of exploration – a loose construction of a life and career, presented visually through ephemeral materials. Dealing in both the personal and professional, these signifiers pique the interest of researchers and art explorers alike, encouraging the finder to continue to follow the line of a paper narrative. This opportunity for discovery occurs in a time capsule, in the unmapped elements of the research puzzle, encouraging the resolution of paper pieces put together in an organic, instinctual way. While working in the Corcoran files, I underwent a process of discovery that revealed personalities and art, both wonderful and strange, including the pulpy and brutal photos of Bud Lee and the early digital art pioneer Ruth Leavitt.

Bud Lee’s photo of actor Clayton Moore portraying the character the Lone Ranger.

Bud Lee’s photo of actor Clayton Moore portraying the character the Lone Ranger.

Born in New York as the son of a career diplomat, Bud Lee (1941-2015) was known for his striking, off-beat, and slightly surreal photographs and portraiture, appearing in publications including Life, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Harper’s, Town & Country, Vogue, Ms., and Mother Jones. His “kitschy, whimsical and Fellini-esque” work covered a wide spectrum of subjects, including the cover of Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together, portraits of legendary directors Francois Truffaut, Frederico Fellini, and Michelangelo Antonioni, and an incredible double portrait of Church of God founders and leaders Dr. O.L Jaggers and Miss Velma.[i]

In addition to his shots of celebrities and art, Lee’s work in education and Civil Rights included documenting four days of rioting in Newark, unrest that left 26 dead and hundreds injured. His image of Joe Bass, aged 12, lying on the ground, shot during an altercation between looters and the police, appeared on the cover of Life brought the “long, hot summer” of 1967 into homes all over America.

Towards the end of his life, Lee suffered a stroke that left him blind in one eye and paralyzed down his whole left side. Exalted as both an artist and journalist, the addition of Lee to the vertical file collection at the AAPG Library provides fascinating and often arresting information both on the work of Lee, and the lived experiences of his many subjects.

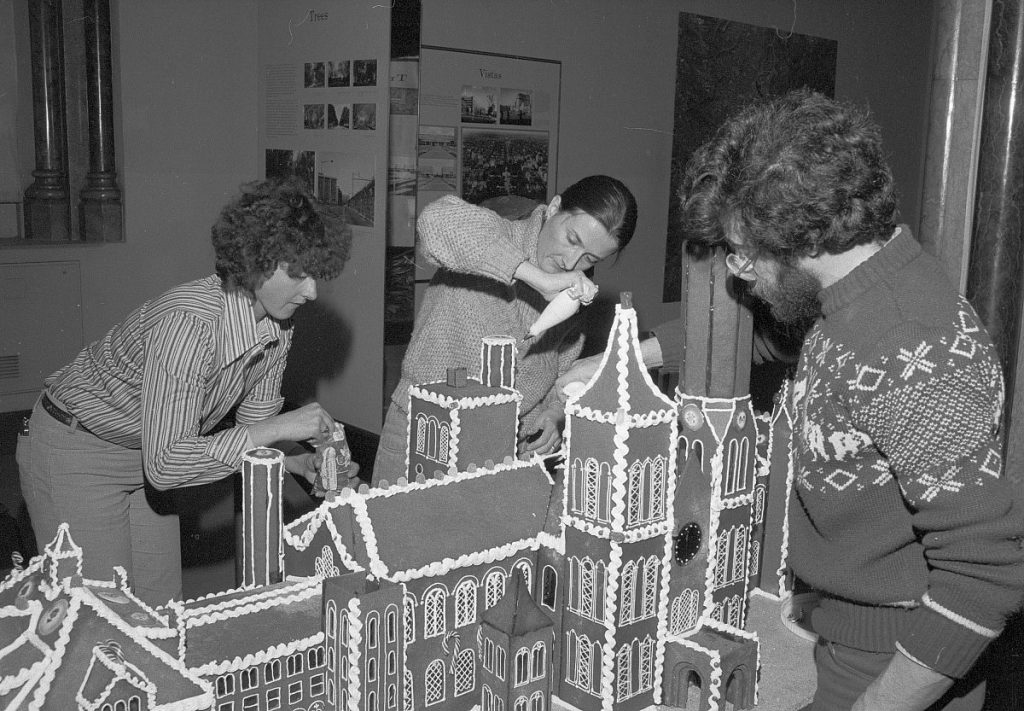

Poster for Ruth Leavitt exhibition at the Martin Gallery, May 13 to June 1, no year provided.

Poster for Ruth Leavitt exhibition at the Martin Gallery, May 13 to June 1, no year provided.

The work of Ruth Leavitt is simultaneously mechanical and organic, and an early example of the exploration of art and technology. Originally introduced to computers by her husband, a computer science professor, Leavitt “learned through osmosis” and brought an Abstract Expressionist sensibility to the format.[ii] While studying with Peter Busa, a fellow Abstract Expressionist who also explored Indian Space painting, Leavitt shifted from the instinctual, physical painting of the Expressionist style to the data-driven, “conscious decision making” of working with a computer as co-collaborator.[iii] After using early software to experiment with distortion and transformation, Leavitt quickly grew frustrated with the technical limitations of existing programs and decided to write her own. Working with coders, Leavitt’s first program stretched and distorted her drawings, which went from “hard-edge, constructivist in style” to having the “lyrical qualities of Abstract Expressionism.”[iv] Through different iterations of her first program, Leavitt explored the dimensions of line and mass, as well as three-dimensional, projected figures and the concepts of attraction and repulsion. These experiments eventually resulted in paintings, graphics, serigraphs (silk screen) and work in film animation.

Leavitt described her sense of excitement over the possibility of creating her own tools and saw programming and technology as enabling creative vision while providing opportunity and access to new, marketable skills. Technology is, by its nature, interdisciplinary, and demands collaboration between human and machine. To Leavitt, the medium was as important as the message, and the technology she employed changed the meaning of her work. Despite this, however, Leavitt felt that there was no such thing as “computer art,” as the artist ultimately wields the power in creation.

As one of the first artists to work with computer programming, and an early female pioneer in digital art, Leavitt’s file supplements our textual narrative of both technology and the visual arts. In addition to her visual experimentation, Leavitt edited Artist and Computer, a 1976 text that featured the work and writings of 35 artists working in the new medium. The insights of her book, which is in the AAPG collection, is now supported by the inclusion of Leavitt herself in our vertical file collection.

Artists on display for the L’s of the Corcoran are:

Raymond Lark (1939- 2005), Ruth Leavitt (1944- ), Bud Lee (1941-2015), Joanne Leonard (1940- ), Les Levine (1935- ), Marilyn Levine (1935 – 2005), Harry Lieberman (1880 – 1983), Harvey K. Littleton (1922 – 2013), Fonchen Lord (1911 – 1993), George Luks (1867 – 1933), Joan Lyons (1937-)

More from The ABCS of the Corcoran Artist Files:

[i] Eric Snider, “A Life In Pictures,” Creative Loafing Tampa, April 6, 2005.

[ii] Ruth Leavitt, Ed., “Ruth Leavitt,” Artist and Computer. New York: Harmony Books, 1976.

[iii] Leavitt, Ed., Artist and Computer.

[iv] Leavitt, Ed., Artist and Computer.

Through the Loupe: A Staff Profile of Media Archives ‘Journeyperson’ Emily Nabasny

This is the second in a series of ongoing blog posts from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI), spotlighting the labor of Smithsonian media collections staff across the Institution. Emily Nabasny currently serves as Video Archives Technician (contractor) on the Media Conservation and Digitization team of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

Learn more about Emily’s work in our upcoming program, AVMPI Presents: The View from Her on March 15th, 2023.

NMAAHC Video Archives Technician, Emily Nabasny. Photo courtesy of NMAAHC Media Conservation and Digitization Specialist, CK Ming.

NMAAHC Video Archives Technician, Emily Nabasny. Photo courtesy of NMAAHC Media Conservation and Digitization Specialist, CK Ming.

Walter Forsberg: Hi Emily! Lovely to meet up with you. Can you start by letting us know where you are on the Smithsonian campus, today?

Emily Nabasny: Hi Walter! I am in the NMAAHC Video Digitization Lab at the Capital Gallery building, where [NMAAHC Media Archivist and Conservator] Blake McDowell and I have been working on rewiring this lab’s equipment and getting it fully back up-and-running. It hasn’t really been in use since before the COVID pandemic. Today, I’m digitizing VHS tapes from the Pearl Bowser Collection. I regularly work here, in the video lab, and next door in the film prep space where we undertake some of the film inspection work that we also do across the Mall at the museum.

WF: It seems as though NMAAHC has multiple media preservation spaces to perform work at. Is that a rarity at the Smithsonian?

EN: It is a rarity. It’s amazing to work at a place that’s so well-funded and well-equipped for this specialized labor. The media team is very privileged to have work spaces at three locations to do our preservation work. Our department has garnered a lot of positive attention for its digitization and conservation work with collections through the museum’s Center for African American Media Arts, and the Great Migration Home Movie Project. We must thank NMAAHC Head of Cataloging and Digitization Laura Coyle and the Robert F. Smith Fund for their immense budgetary support.

WF: Can you speak about how you first got interested in film and audiovisual media?

EN: For me it started very young. I grew up watching classic movies—like Hitchcock films, Universal Monsters, Vincent Price, and Turner Classic Movies—so I was exposed early on to a lot of film history. But my interest in the tangible archiving side of things really came from my grandfather Dennis L. Crow, who worked as a professional photographer. We had a lot of family slide shows and home movie projections—not only of family vacations, but also material my grandfather shot on his international work trips. They were exciting to experience as a kid, and I was fascinated by the technology. Being able to hold slides up to the light to see the images, watching the film projector spin the reels—that kind of thing.

Emily Nabasny’s grandfather, Dennis L. Crow, shooting in New York City.

Emily Nabasny’s grandfather, Dennis L. Crow, shooting in New York City.

WF: Did you get involved in shooting film, as well?

EN: I did a lot of still film photography, which my mother is also proficient at, and shot some VHS home movies. I would play around with recording, but I was more interested in the technical side of things. Watching tapes after they were shot and adjusting the settings. I was the kid in the house who would sit in front of the old CRT television set with the knobs on the front, altering the saturation, contrast, and color balances to the extremes.

I ended up majoring in Film Studies in undergrad at the University of Pittsburgh, where I learned how film reels became lost in old trunks, abandoned houses, and filled-in old swimming pools, then were ultimately rediscovered and preserved. To me, that ‘media archaeology’ side of things is extraordinary and exciting.

WF: You ultimately enrolled in the NYU Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) graduate program. I remember advising you on a project about the defunct Kodak New York City corporate archives.

EN: That’s right! When I was getting closer to figuring out what I wanted to do after college, my fascination and love of film and history—along with my penchant for organization—led some people to mention library science, which lead me to the NYU MIAP program. That’s how I found out about media archiving. And I do remember those Kodak archive boxes. Hundreds of copies of scientific publications and information about film chemicals. That was a great collection inventory project.

WF: There always seems to be someone in each family with the genealogical-interest gene. Are you that person for the Nabasnys?

EN: Oh yeah, definitely. I currently have about eight boxes of family photos in my apartment that I’ve been scanning. Our family has a collection of thousands of photos. I’ve digitized all of our home movies and, several years ago, I surprised everyone by editing some holiday clips together. Because I’m an archivist, everything is receiving detailed metadata. [Laughs]

WF: Of all the Smithsonian staff I can think of, you’re the person I know who has worked for the most museums. Has it been a decade since you started? Of course, I owe it to our Unbound blog readership to request that you run down the list for us.

EN: Almost a decade, but I’ve been here closer to eight years. It feels unusual that I’ve worked at five different Smithsonian units. I started my Smithsonian journey in 2015 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (HMSG) where I was brought in to digitize and migrate artworks recorded on Betacam videotape, and to work with [Variable Media Conservator] Briana Feston-Brunet to set up workflows and processes for time-based media conservation and to build out their media lab. I was there for two years and worked on documenting and ingesting born-digital media artworks into the DAMS. During that time (and in 2021), I worked with [Senior Conservator] Dana Moffett at the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA) on their time-based media art collection, creating collections policies and ingesting digital assets into the DAMS. A lot of the public is unaware of NMAfA. It’s small compared to many of its counterparts, but it hosts an incredible collection.

My third stop on the Smithsonian tour was the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) Ralph Rinzler Archive to undertake an enormous item-level inventory of video documentation of past Folklife Festivals. Most people know the Folklife Center from its annual festival hosted on the National Mall and from Folkways Records, which are both admittedly awesome, but fewer people know that Folklife has an amazing collection of materials documenting international cultural heritage from work they do.

WF: Folklife Media Archivist Dave Walker shared a 2002 highlight video from the Silk Road-themed festival for our recent, AVMPI presents: A Zoom with a View streamcast. Definitely great stuff at CFCH.

EN: Absolutely. It was eye-opening to learn more about their vast collections, and I ended up inventorying about 9,000 videotapes. Unfortunately, the scope of my project did not allow me time to watch any of the tapes, but I would love to. They have real variety and unique gems in their collections. My fourth location before coming to NMAAHC was at your own Smithsonian Institution Archives (SIA). I worked with [Digitization Manager] Kira Sobers on cataloging the media collection elements of the Smithsonian World television program. Smithsonian World was a 1980s co-production with the PBS affiliate in Washington, WETA-TV.

Title credit from the 1980s PBS series, Smithsonian World.

Title credit from the 1980s PBS series, Smithsonian World.

WF: Ahem, I think you mean the “groundbreaking, six-season, Emmy Award-winning series, Smithsonian World.” [Laughs]

EN: [Laughs] Yes, that’s the one! I think SIA was given much of the collection by a former producer and the AV collection materials had never been fully cataloged, so SIA was never certain of what they had in terms of content. It’s mainly 16mm film, with a few reels of 35mm, ¼” audiotape, and most of the finished programs on one-inch videotape. The program was shot on 16mm, so there are production outtakes and original episode segment reels that were later combined on film to make the episodes. My project started with working on rehousing film and cataloging the AV materials for seasons 1 and 2. When COVID hit in 2020, we had to reconfigure my work to center on researching the series and describing episode content because I had to work from home. When that rehousing project eventually continues, they will be able to use my content information to organize film reels within the seasons, and to assist researchers.

The series is from the 1980s, so watching episodes was like being in a time machine. Some of the most fun things I watched were a ‘fashion’-themed episode narrated by James Earl Jones, a segment where a wandering minstrel attempts communication with animals through music, and an episode about developing and constructing the Hubble telescope. That was particularly fascinating—hearing their hopes for the project and watching, given what we know now about how that ended up…I could talk about this show for hours. Incredible interviews and footage with Smithsonian scientists, researchers, staff, and a whole spectrum of other innovators.

Emily Nabasny inspects film elements from 1980s PBS series, Smithsonian World, inside the laboratory at Smithsonian Institution Archives. Photo courtesy of Emily Nabasny.

Emily Nabasny inspects film elements from 1980s PBS series, Smithsonian World, inside the laboratory at Smithsonian Institution Archives. Photo courtesy of Emily Nabasny.

WF: Tell me more about your current role as Video Archives Technician at NMAAHC.

EN: After the Smithsonian World project, I moved to work with the six-person ‘Dream Team’ at NMAAHC. NMAAHC has four full-time media archiving staff members and two contractors, including myself, all working to catalog, preserve, conserve, and share the audiovisual collections. I assist with film rehousing and digitization projects, though my current main project is working with a video collection the museum acquired from author, director, producer, archivist, and founder of African Diaspora Images, Pearl Bowser. Pearl’s video collection is comprised of her own documentary work, as well as copies of ‘race films’ by Oscar Micheaux, films by African American filmmakers, documentaries about African American history, and recordings of local television station broadcasts. I have started by researching and digitizing her VHS collection, and then I will move to her U-matic format video collection. Other team members are working on digitizing and cataloging her audiocassettes.

WF: What’s been the most eye-opening part of your career to this point?

EN: When I was in school, I would have *never* expected to work in an art museum. It simply wasn’t part of my career vision. But, I was open to working with different types of media materials, and working on media-based artworks at HMSG and NMAfA was a constant learning experience because it is so different from archival materials. There are many aspects one must consider when working with media formats, and even more considerations when working with art and artists. When you’re pulling a media artwork piece out of storage for exhibition, there’s always the question: Does it still work? And, if it doesn’t work: What are we allowed to undertake as an intervention to get it working? The technological obsolescence aspect of whether or not a museum is able to exhibit an older media art piece was a fun challenge. It was thrilling to be part of those decisions in time-based media art conservation. I remember working with Briana at the Hirshhorn on the artwork At Hand by Ann Hamilton, whose audio files were stored on an outdated SATA hard drive, and we went on a wild chase trying to find the right combination of cables and adapters to get the files off the drive. At NMAfA, I was part of a conservation meeting with Sue Williamson about her work Can’t Remember, Can’t Forget, which is an interactive artwork that was originally exhibited on a computer from the 1990s. We talked with Sue about what was integral to the exhibition and meaning of her artwork, both technologically and aesthetically. ‘What is the art?’ is a fascinating question to consider when looking at media art, because its often more than viewers think.

WF: Do you have any career advice to folks interested in working in audiovisual preservation?

EN: I echo Pam Wintle’s comment in your last blog to be curious and remain open to new experiences. I’ve worked several jobs that I would have never thought I would, but I learned a lot and had great experiences. Being open to the new and unexpected is a big part of life and you never know where a different job or new collection might take you. After working at five different Smithsonian units, I can say each was different than I had expected. Every archive, every collection is unique. There will be institutional things you have to adapt to, collection elements to learn and consider, and constantly new technology to learn. There’s certainly no shortage of collections and incredible projects at the Smithsonian!

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating women’s stories in our second AVMPI Presents program. Join us for a screening of audiovisual materials from across the Smithsonian that represent both the spectrum of American women’s history and the diversity of our film and video collections.

Join us to hear more about Emily’s work, the Pearl Bowser Collection, and more!

Ascending Pikes Peak in a Locomobile

Two men set off to ascend a mountain located in Colorado called Pikes Peak. Their transportation was a vehicle called the Locomobile, and this trade catalog traces their journey on an August day over a century ago.

The trade catalog is titled Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901) by Locomobile Co. of America. It begins with a descriptive account of the journey, written by W. B. Felker, titled, “Up Pike’s Peak in a Locomobile.” Mr. Felker’s companion for the trip was Mr. C. A. Yont, an amateur photographer. Their goal was to drive a Locomobile to the summit of Pikes Peak at an altitude of over 14,000 feet.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), front cover.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), front cover.

Before we follow their journey, let’s learn a little about the vehicle they used. It was a steam vehicle called a Locomobile. Several testimonials written by satisfied customers are shared at the end of this catalog. A common theme found throughout these testimonials is the vehicle’s ability to handle hills, long stretches, and poor road conditions.

One testimonial, dated December 15, 1900, was written by Dr. W. B. French of Washington, D.C. According to that testimonial shared on page 22, Dr. French had ridden 5,880 miles in the Locomobile since February 21, 1899, averaging about 580 miles per month. The doctor commented, “This mileage includes many country runs adjacent to this city, over some of the most villainous roads that were ever made, but the ’Loco’ will go even over such roads if it is given steam and some little experience in handling.”

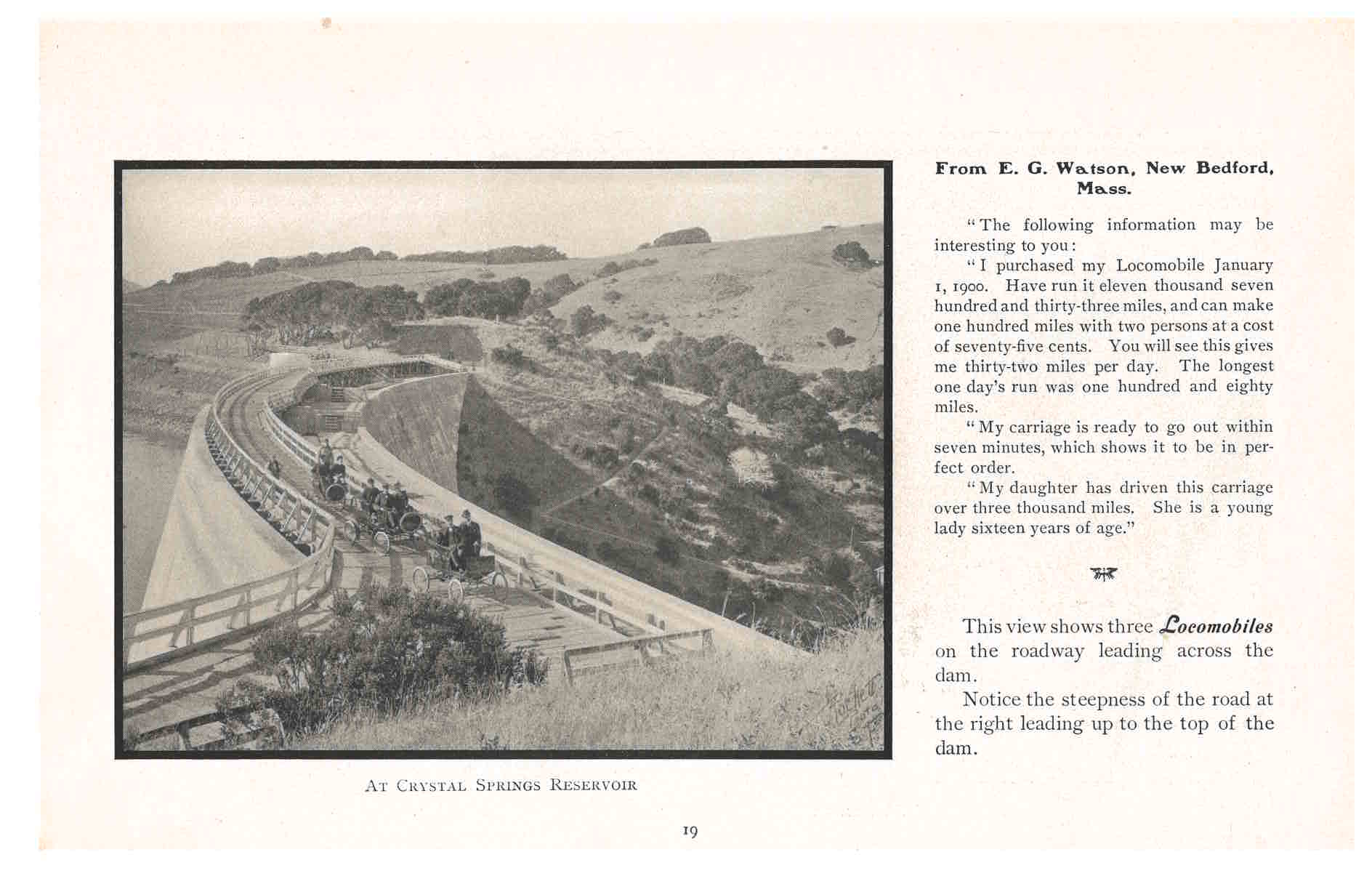

Throughout these testimonial pages, there are also images of Locomobiles in various locations. The image shown below illustrates three Locomobiles on the road leading across the dam at Crystal Springs Reservoir in California. Its caption in the catalog points out “the steepness of the road at the right leading up to the top of the dam.”

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 19, three Locomobiles at Crystal Springs Reservoir.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 19, three Locomobiles at Crystal Springs Reservoir.

Now let’s delve deeper into the journey of Mr. Felker and Mr. Yont as they ascended Pikes Peak in a Locomobile. Their preparation began on a Sunday, as they traveled 86 miles from Denver to Cascade where they filled their tanks to prepare for the following day’s adventure. Mr. Felker remarked that “some of the old-timers had considerable fun at our expense guessing how far up” they would go. They were also told that the wagon road had not been used much by wagons in the past two years and had gone “to ruin” since the cog railroad was built in 1891.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 3, beginning of account titled “Up Pike’s Peak in a Locomobile” by W. B. Felker.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 3, beginning of account titled “Up Pike’s Peak in a Locomobile” by W. B. Felker.

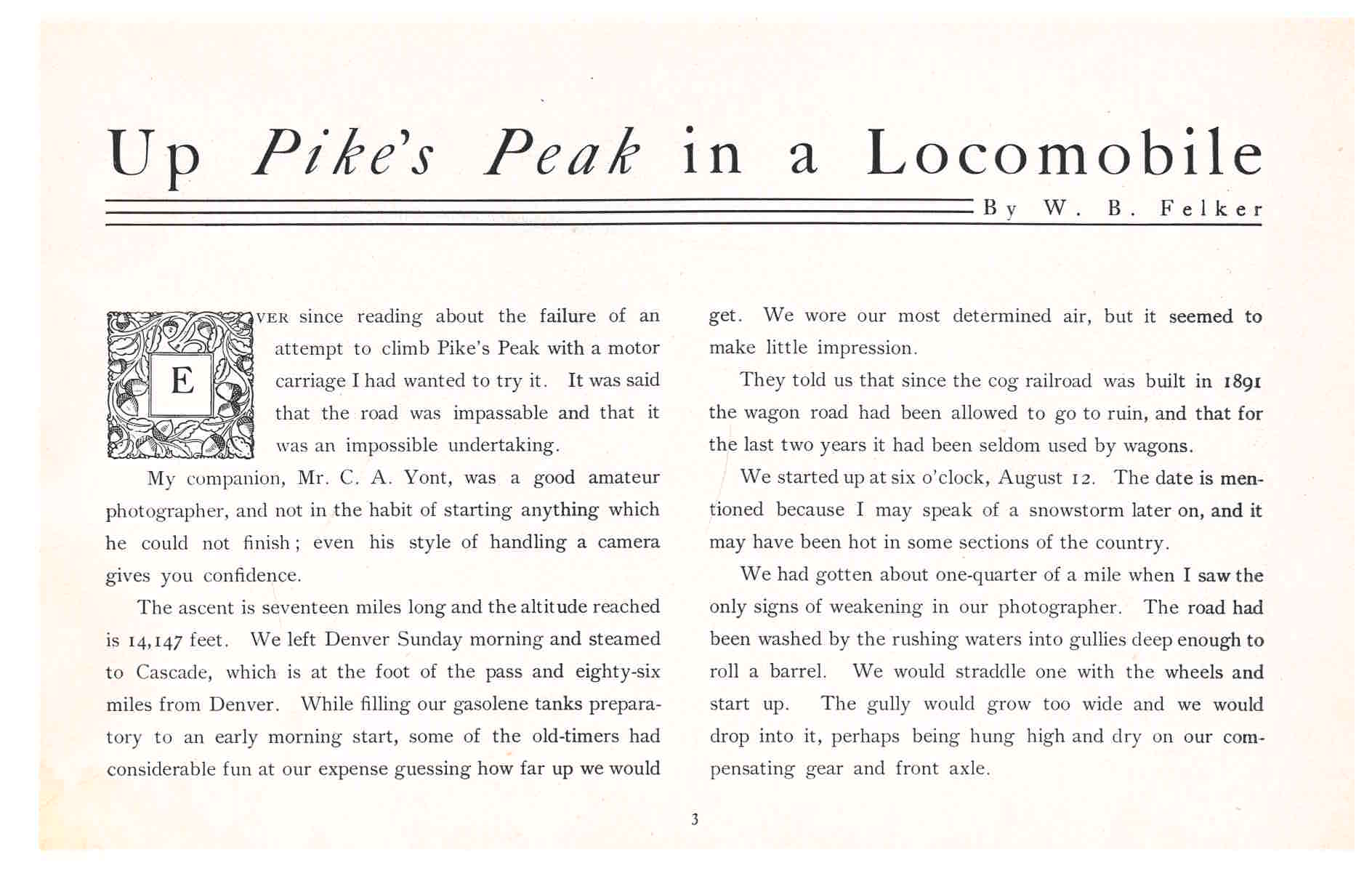

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 4, the two men on a portion of the “Old Stage Road” with the Locomobile.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 4, the two men on a portion of the “Old Stage Road” with the Locomobile.

Their ascent to the summit of Pikes Peak began at 6:00 am on August 12. After the first quarter of a mile, they reached a spot where the “road had been washed by the rushing waters into gullies deep enough to roll a barrel.” Straddling the gullies with their wheels, they continued on. However, they discovered that as a gully became wider, they “would drop into it.” It took three hours to ascend the first two miles. By that time, they decided to stop for a meal consisting of three sandwiches and a pickle. They reached the “Half-way House” at about 11:00 am and thought the worst was behind them.

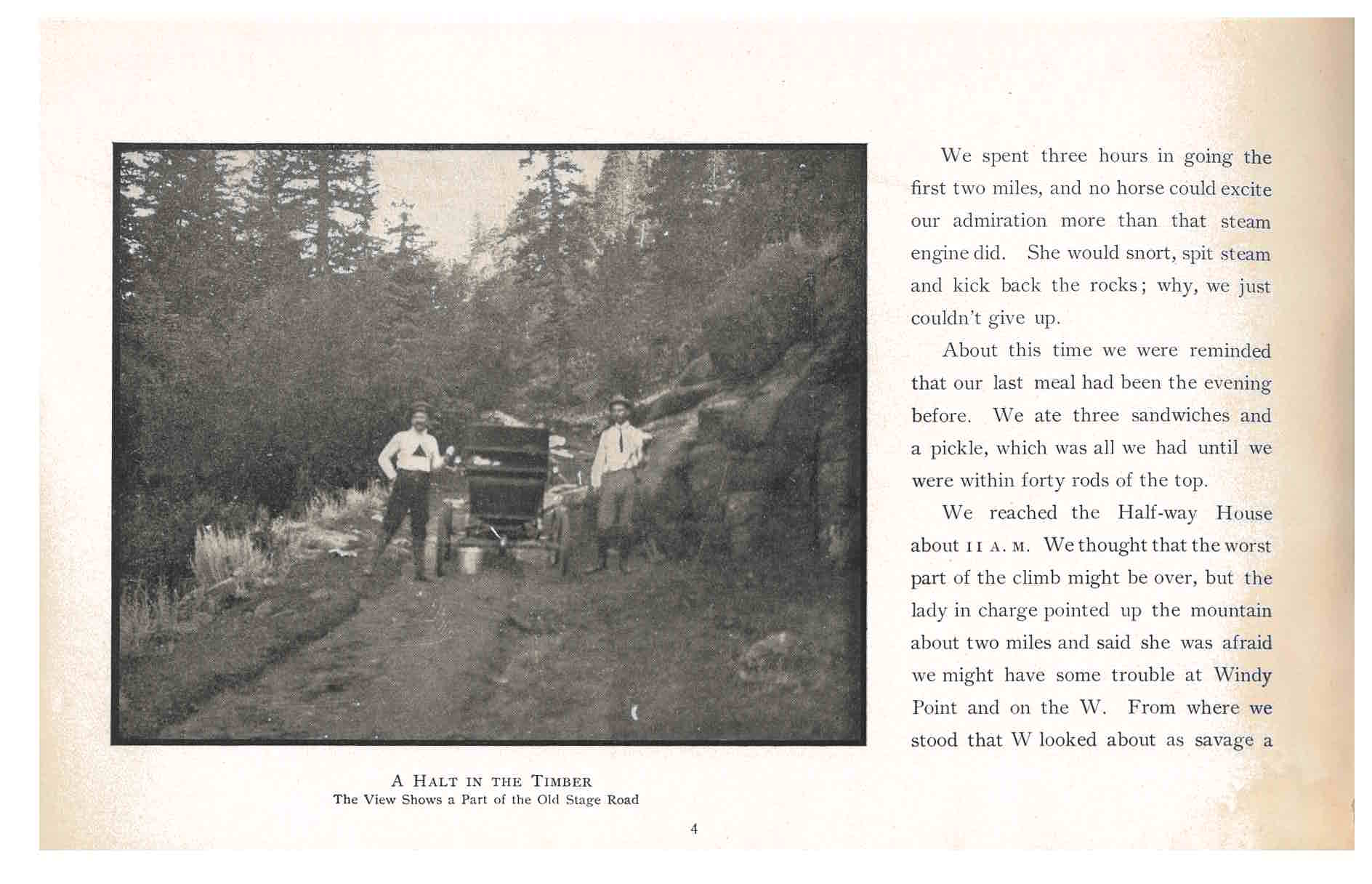

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 5, rest stop at the Half-way House.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 5, rest stop at the Half-way House.

But the lady in charge informed them they “might have some trouble at Windy Point and on the W.” Mr. Felker writes, “From where we stood that W looked about as savage a piece of scenery as a crooked piece of lightning.” That led to checking all the machinery of their vehicle, including every bolt and nut, before continuing their journey.

Soon after setting off, they reached a bridge where they “pretty nearly had a runaway…” Mr. Felker writes, “Yont was kicked by a log thrown up by the whirring wheels, and when the machine jumped I was straightened out like a flapping flag.” He continues by remarking that he had “seen some rather bogus bridges, but that beat me.”

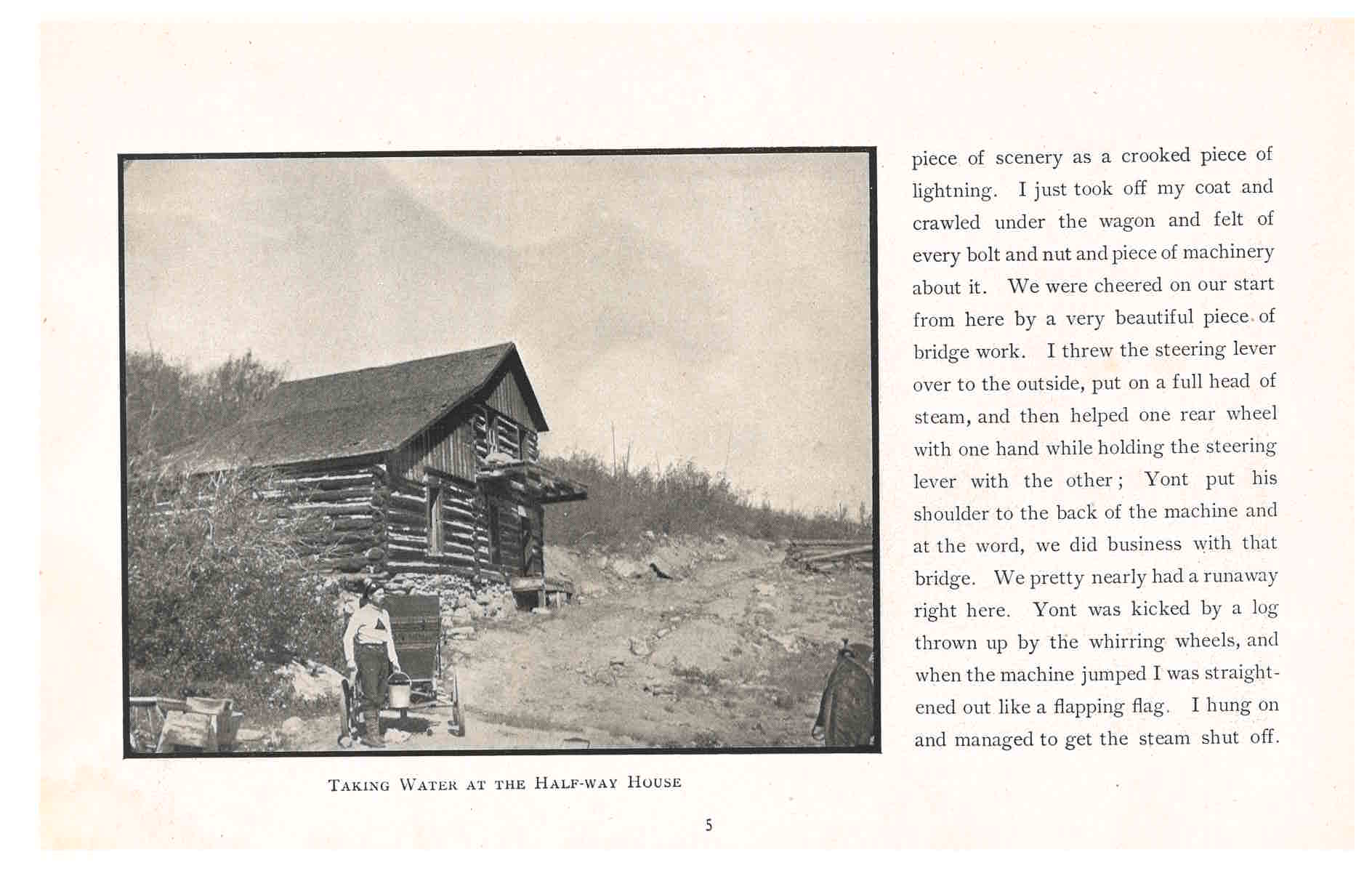

As they continued along, they had the opportunity to marvel at the “Grand View,” illustrated below, which from his description appears to be exactly that. And another landmark was “Windy Point” for which Mr. Felker writes, “One knows when they get there.”

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 6, a stop at “Grand View.”

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 6, a stop at “Grand View.”

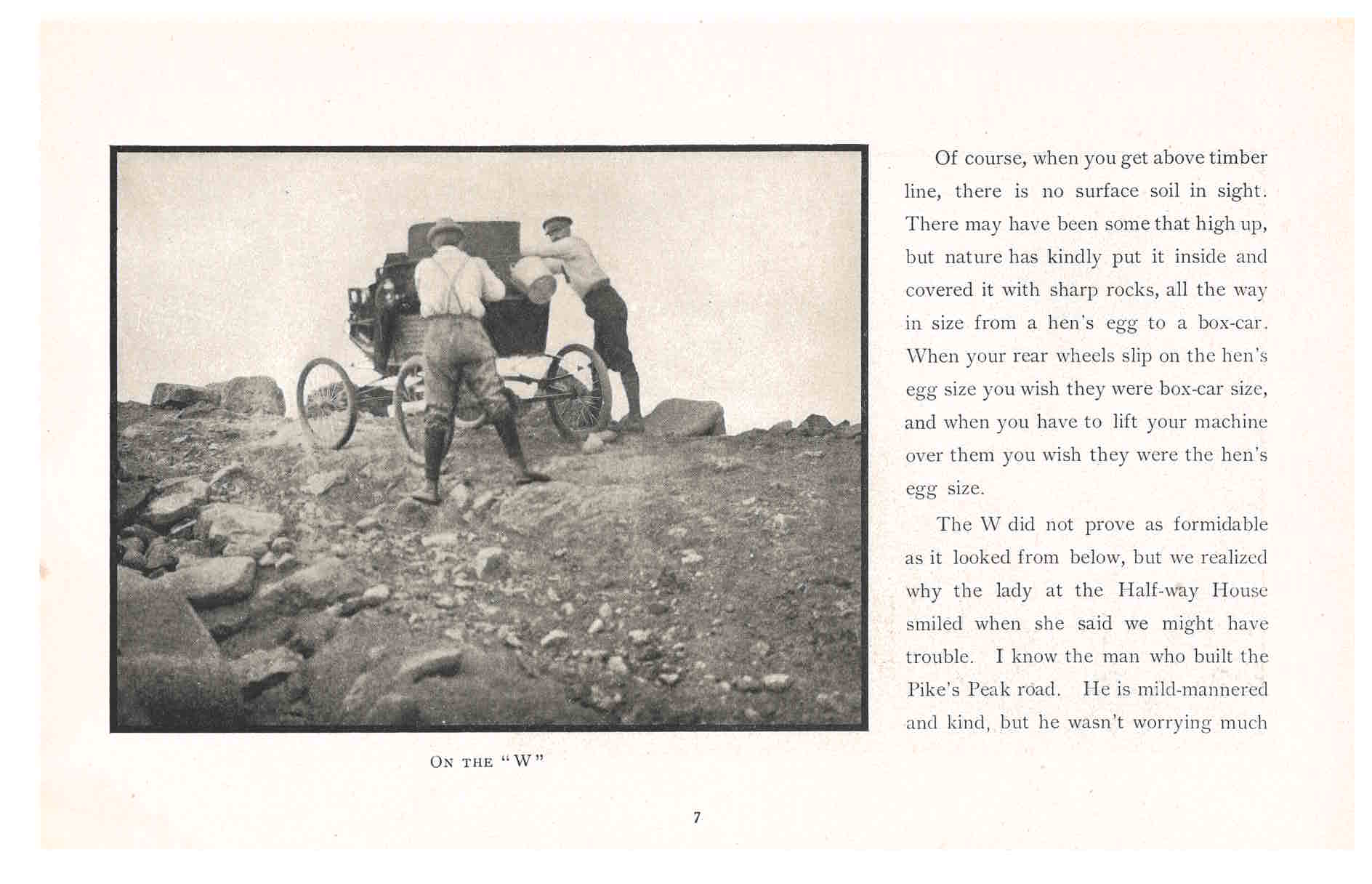

The lady at the “Half-way House” had warned them of the “W” but it turned out to not be as “formidable” as they had feared. For an idea of how the “W” looks, Mr. Felker suggests turning a letter “W” sideways. Though he cautions that it does not convey how a person actually feels while “on one of the points of the W about 13,000 feet up in the air.”

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 7, tending to the Locomobile on the “W.”

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 7, tending to the Locomobile on the “W.”

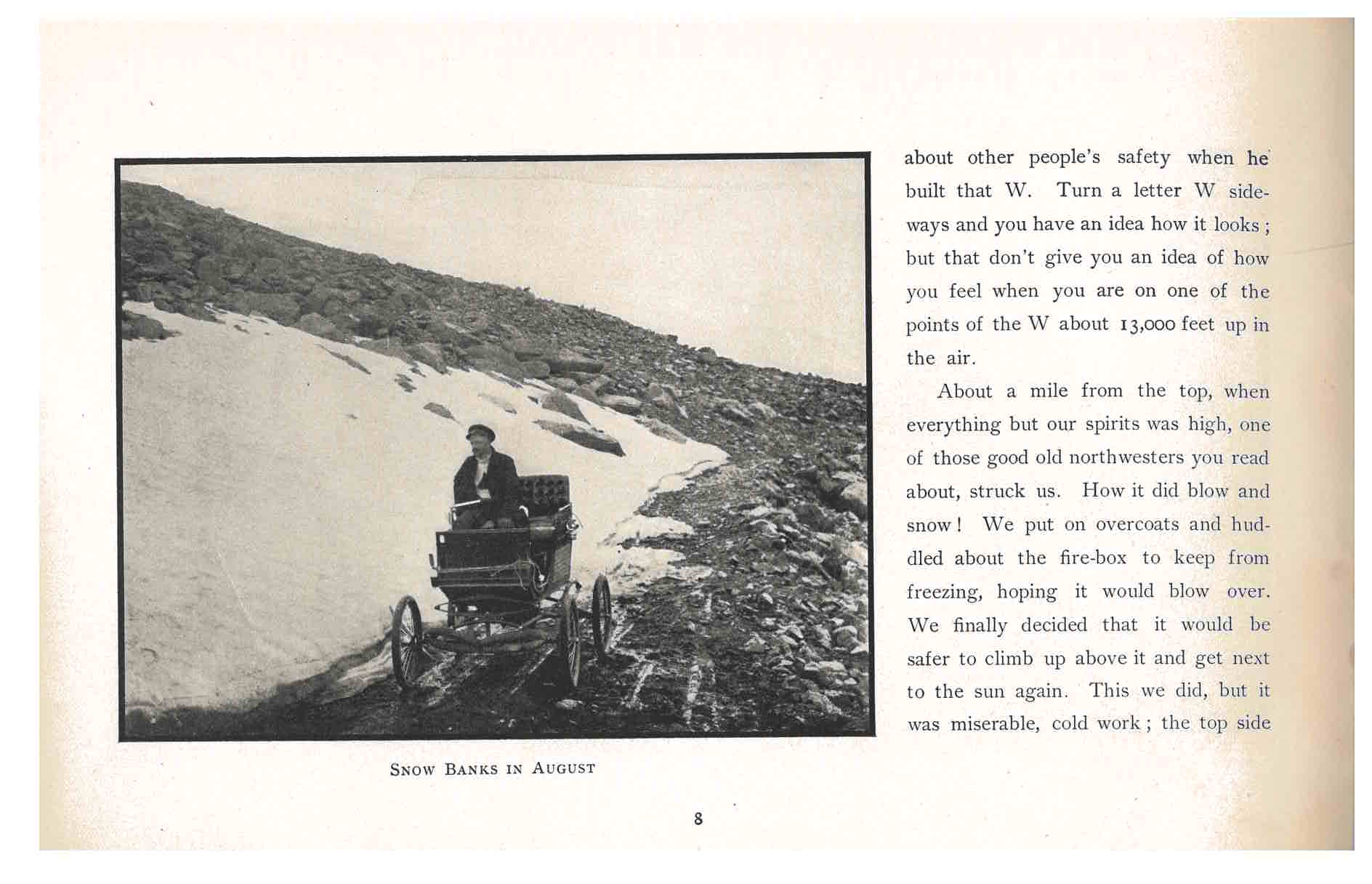

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 8, snowbanks in August.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 8, snowbanks in August.

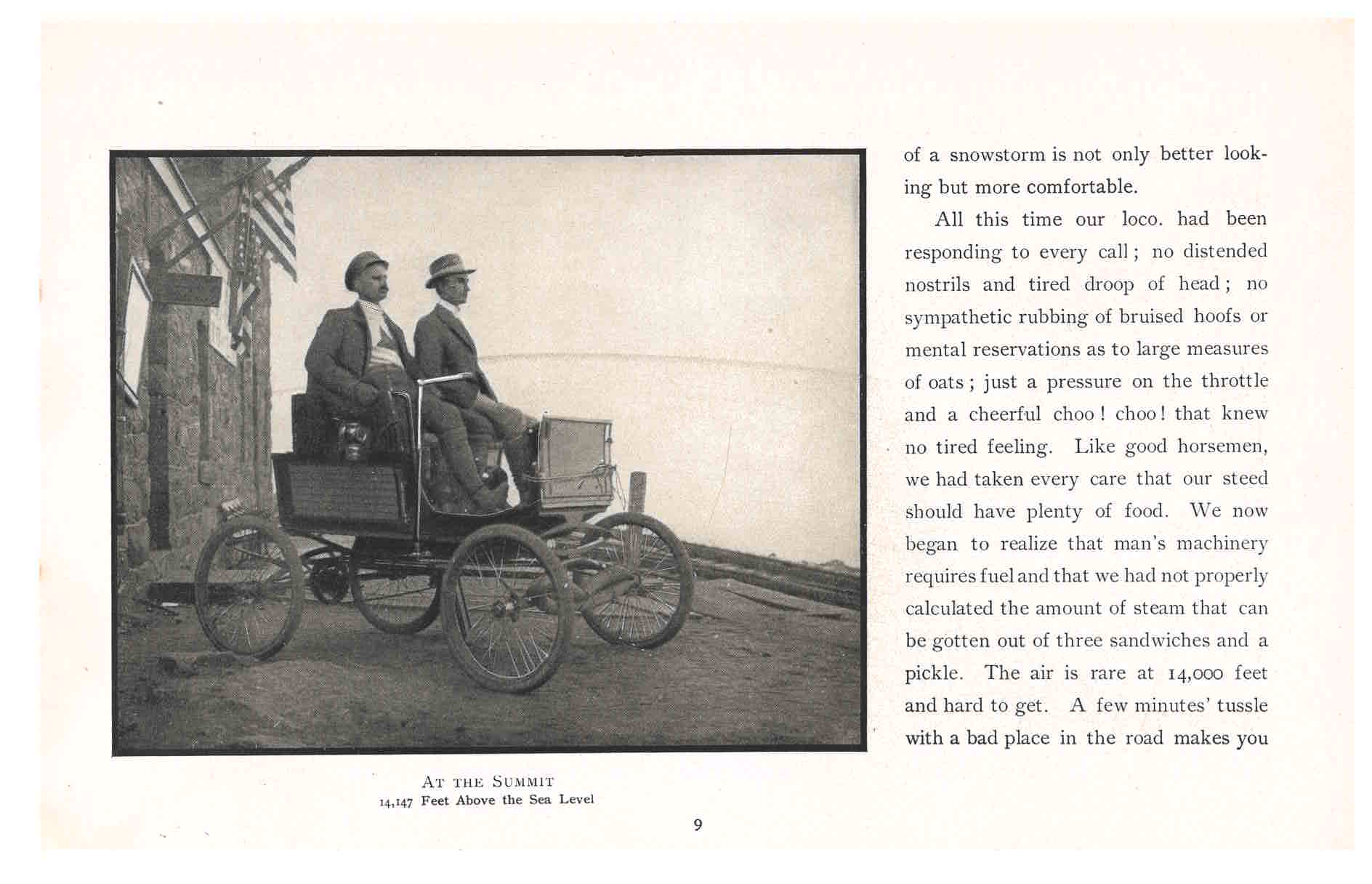

And then on that August day, about a mile from the summit, they encountered a snowstorm. After passing the storm, they realized they were hungry and also struggling with the air and high altitude. A horseback rider came along and offered to go ahead and find food for them, and with that assistance, they reached the summit. At the top, they paused for photos, food, and coffee.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 9, at the summit of Pike’s Peak on the Locomobile.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 9, at the summit of Pike’s Peak on the Locomobile.

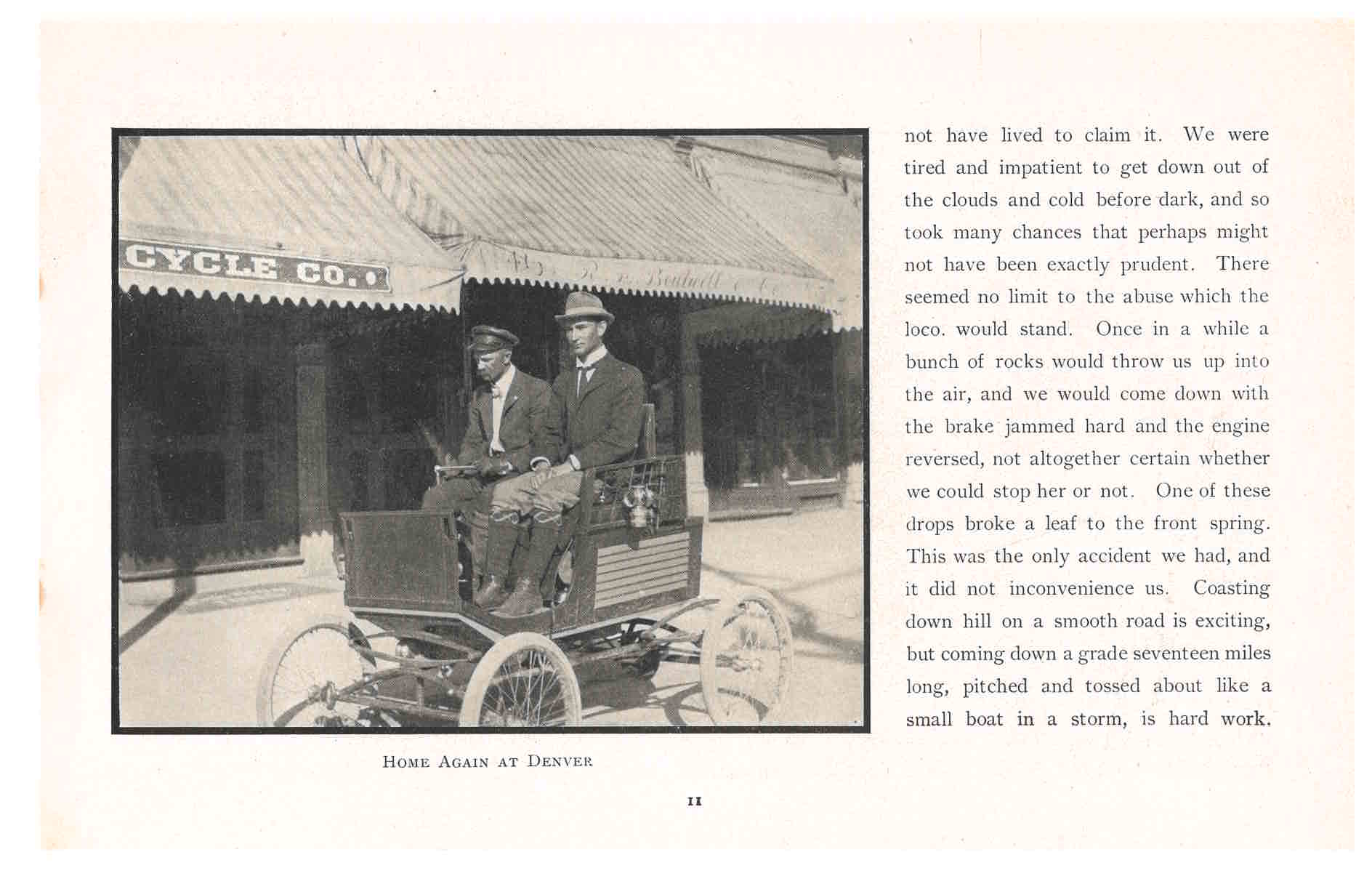

Their return trip back down turned out to be “perhaps more dangerous, but not such hard work.” Due to their tiredness and impatience to get to the bottom before dark, they took more chances. After passing the “Half-way House,” they continued their journey with the assistance of their “side-lights” as they made their way through the darkness. They discovered more bumps on the road than they had on the way up, and Mr. Felker wrote that their brake was so hot they “could smell the burning leather, and the metal parts could not be touched with the hand.”

According to Mr. Felker’s account, by 9:30 pm they reached Cascade and headed to bed as they “were too tired to stand around and brag much.” The next morning, the two men departed Cascade, traveled through Ute Pass to Manitou, ate breakfast in Colorado Springs, and reached Denver at 4:00.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 11, home in Denver.

Locomobile Co. of America, New York, NY. Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901), page 11, home in Denver.

Up Pike’s Peak and Elsewhere in a Locomobile (1901) and other Locomobile Co. of America trade catalogs are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Introducing the #FunnList

This Black History Month, we’re excited to introduce the #FunnList: a spotlight on Black women in science from Smithsonian history.

The Funn List builds off the Smithsonian Funk List, the brainchild and namesake of Vicki Funk (1947-2019). Now maintained by American Women’s History Initiative Digital Curator Liz Harmon, the Funk List is an ever-expanding data set documenting over five hundred Smithsonian women in science, past and present.

The vast majority of women on the Funk List are white. Ellis L. Yochelson and Mary Jarrett’s 1985 retrospective, 75 Years in the Natural History Building, crystallizes this disparity: “At the present time [in 1985], though other minority groups are represented, there are no American blacks on the scientific staff.” An understatement follows on the next page: “The historical record is not one to be particularly proud of.”

Despite institutional racism, Black women have fought to forge careers in the sciences at the Smithsonian since at least the mid-twentieth century. The #FunnList campaign from Smithsonian Institution Archives honors the unique stories of these scientists—starting with its namesake, Annette Jones Funn.

A #FunnList collage featuring, clockwise, from left: Annette Jones Funn; Lisa Stevens; Sophie Lutterlough; Margaret Collins.

A #FunnList collage featuring, clockwise, from left: Annette Jones Funn; Lisa Stevens; Sophie Lutterlough; Margaret Collins.

The Funn in the #FunnList

The Funn List is named after Annette Jones Funn (1942-2016), a microbiologist with the Smithsonian Oceanographic Sorting Center (SOSC) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Funn spent the years 1966 and 1967 as a technician with the Smithsonian Oceanographic Sorting Center. Founded a few years earlier, SOSC was responsible for cataloging, preserving, and distributing marine specimens for research worldwide.

The Oceanographic Sorting Center was headquartered south of the National Mall, in Washington, DC’s Navy Yard area. Funn’s work, however, took her even farther afield.

In September 1967, Funn joined an expedition of the Southeastern Pacific Biological Oceanographic Program (SEPBOP). The Anton Bruun’s Cruise 18B set sail from Callao, Peru, traveling through the Galapagos to Guayaquil, Ecuador. Along the way, Funn collected invertebrates and algae for SOSC, and preserved specimens gathered from midwater trawls.

Funn would go on to a decades-long career at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, where she melded her microbiology expertise with a focus on public health. As part of her work in the FDA’s Office of Consumer Affairs, Funn served as a public health advisor for the Health and Human Services Secretary’s Health Promotion Initiative.

Funn’s community advocacy extended well beyond her professional duties. As an undergraduate at Virginia State University, she was appointed by Martin Luther King, Jr. to lead a “platoon” in a civil rights march held near the college. Later, she would hold leadership roles in a veritable bevy of local and national Black and women’s organizations: the National Council of Negro Women, the League of Women Voters, and the NAACP, to name a few.

Funn List Spotlights

Annette J. Funn | Margaret Collins | Margaret Santiago | Sophie Lutterlough | Lisa Stevens

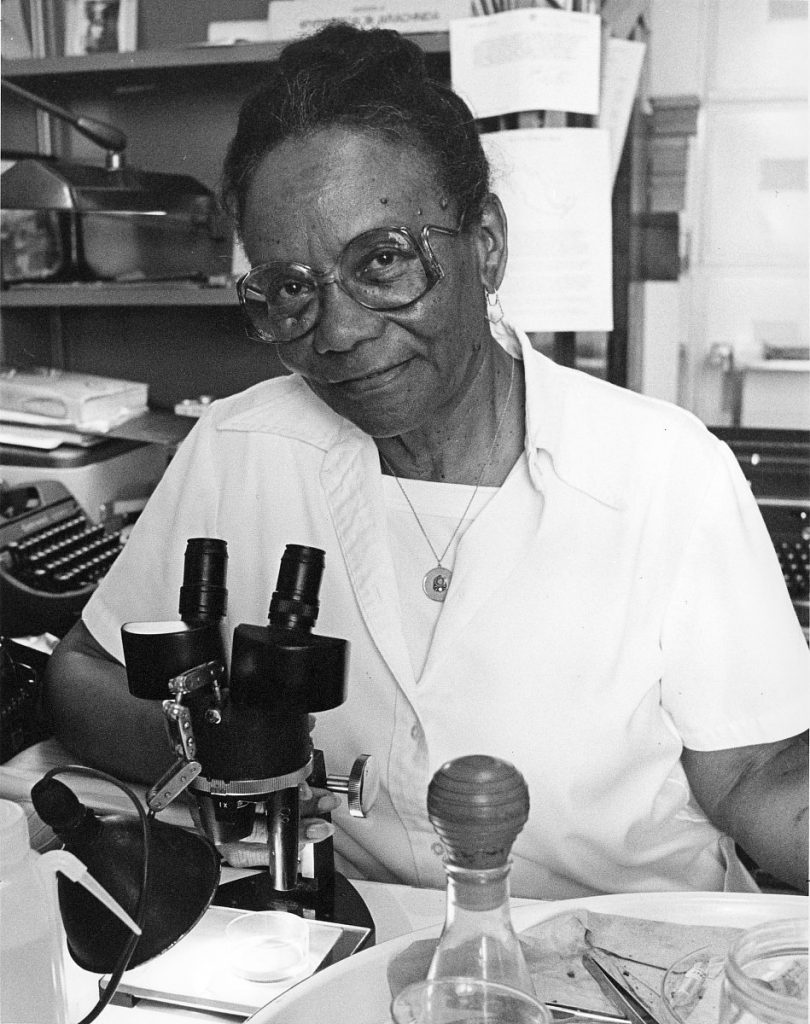

Sophie Lutterlough at a Microscope, 1983. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Sophie Lutterlough at a Microscope, 1983. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Further Reading:

“Concerned Black Women honors Annette Funn” by Tamara Ward, Southern Maryland News

Inspiring African American Women of Calvert County by Friends of Calvert Library

Join us for “Music HerStory: Women, Zines, and Punk”

February 28th, 7 pm ET

Register via Zoom

Zines are celebrations of self-expression. These unique documents often combine first-person narratives and frank opinion pieces with interviews, reviews, and musings on art, music, and culture. Popular today, zine use was propelled by the riot grrrl movement in the early 1990s. They connected like-minded readers and musicians through writing about women’s issues, perspectives, and experiences. Zines continue to promote community-building and creativity, especially among young women.

In this virtual panel discussion, we’ll explore the history of zines as a grassroots medium, the impact of the riot grrl movement on modern zine creators, and the role libraries and archives play in preserving this material.

Featuring:

- Allison Wolfe, co-creator of Girl Germs, Bratmobile, and Riot Grrrl

- Molly Neuman, co-creator of Girl Germs, Bratmobile, and Riot Grrrl

- Osa Atoe, creator of Shotgun Seamstress

- Michele Casto, librarian, People’s Archive, DC Public Library

Moderated by Meredith Holmgren, curator of Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change

Girl Germs and Riot Grrl zines, on display in Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change. Photo by Carolyn Thome, Smithsonian Exhibitions.

Girl Germs and Riot Grrl zines, on display in Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change. Photo by Carolyn Thome, Smithsonian Exhibitions.

This program is part of the exhibition Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change, organized by Smithsonian Libraries and Archives and the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. The exhibition, which is now on view in the National Museum of American History, received support from the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative.

Related Content:

- Music HerStory: Zine Workshops, March 4th. Details coming soon!

- Bernice Johnson Reagon mini-comic created for Music HerStory: Women and Music of Social Change.

California Rare Books School Comes to Smithsonian Libraries and Archives

Interested in exploring books and archives dating back to the 13th century? Join our summer rare book school!

The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, in collaboration with UCLA’s California Rare Book School (CalRBS), is excited to present seven (7), week-long, intensive rare book courses at the Smithsonian from August 14-18, 2023. Participants will benefit from an expert faculty and the wealth of special collections of rare books, manuscripts, and archival materials. All attendees will receive in-depth instruction over five consecutive days in specialized topics with authorities in their fields.

Courses and Instructors Include:

- The Power of Display: Books as Transformative Tools in Exhibitions (Jennifer Cohlman Bracchi and Vanessa Haight Smith)

- The Social and Material Lives of Comic Art, or, How Comics Get Around (Charles Hatfield)

- Introduction to Audiovisual Preservation (Siobhan Hagan and Walter Forsberg)

- Data Born in Literature: 600 Years of Special Collections Serving the Planet (Martin Kalfatovic)

- The Nature of Science in Manuscript and Print (Lilla Vekerdy and Leslie Overstreet)

- Introduction to Western Codicology (Ilya Dines)

- Artist Books at the Smithsonian (Brad Freeman)

Select a course above to learn more! From medieval Western manuscripts to comic art, there is something for everyone.

CalRBS was founded in 2005 as a non-degree education program dedicated to providing the knowledge and skills required by collectors and professionals working in libraries, archives, museums, and rare book communities. Read more about CalRBS.

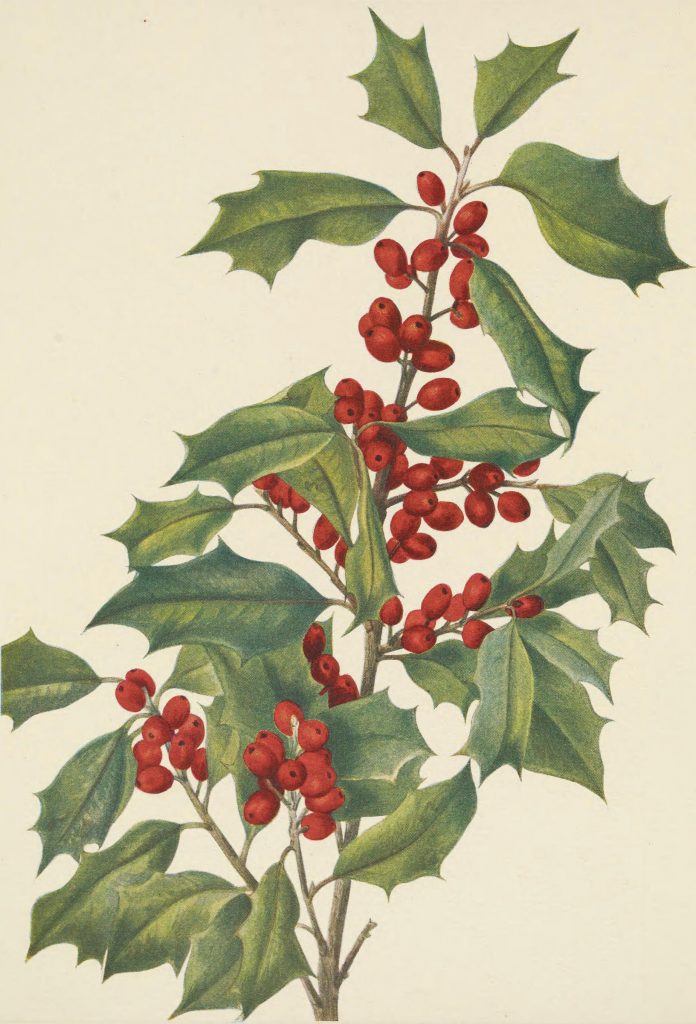

Researching Russia Leather

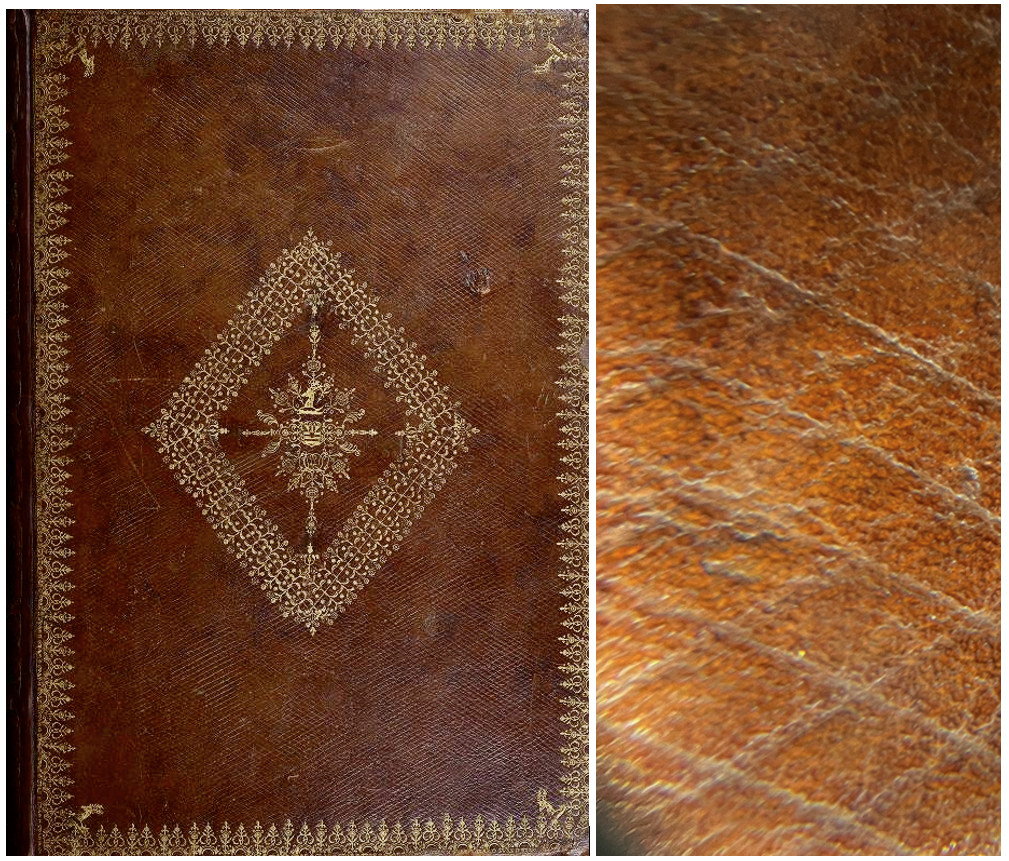

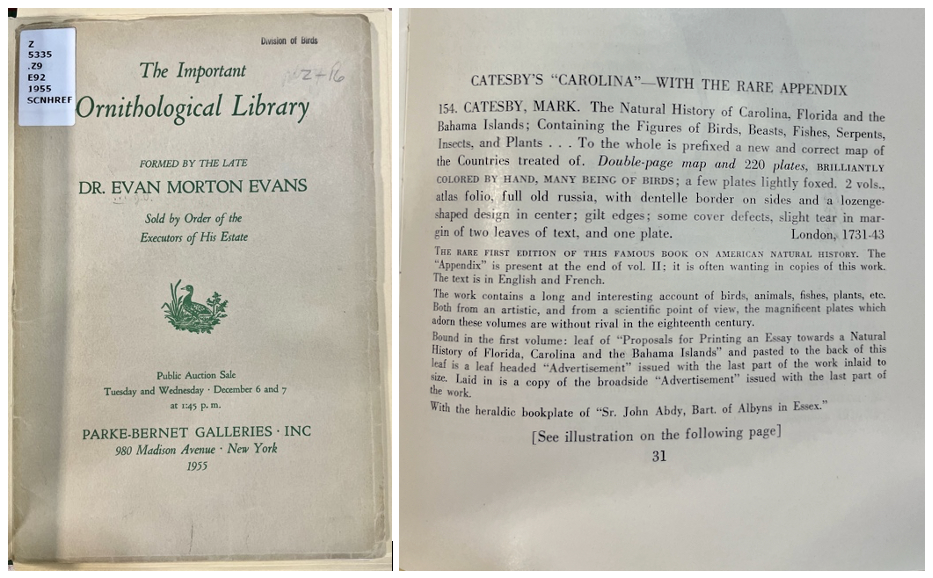

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ new exhibition, “Nature of the Book“, explores the use of natural materials in books from the hand-press era, from the mid-1400s through the mid-1800s. One of the materials the exhibition examines is leather, which was commonly used for book coverings.

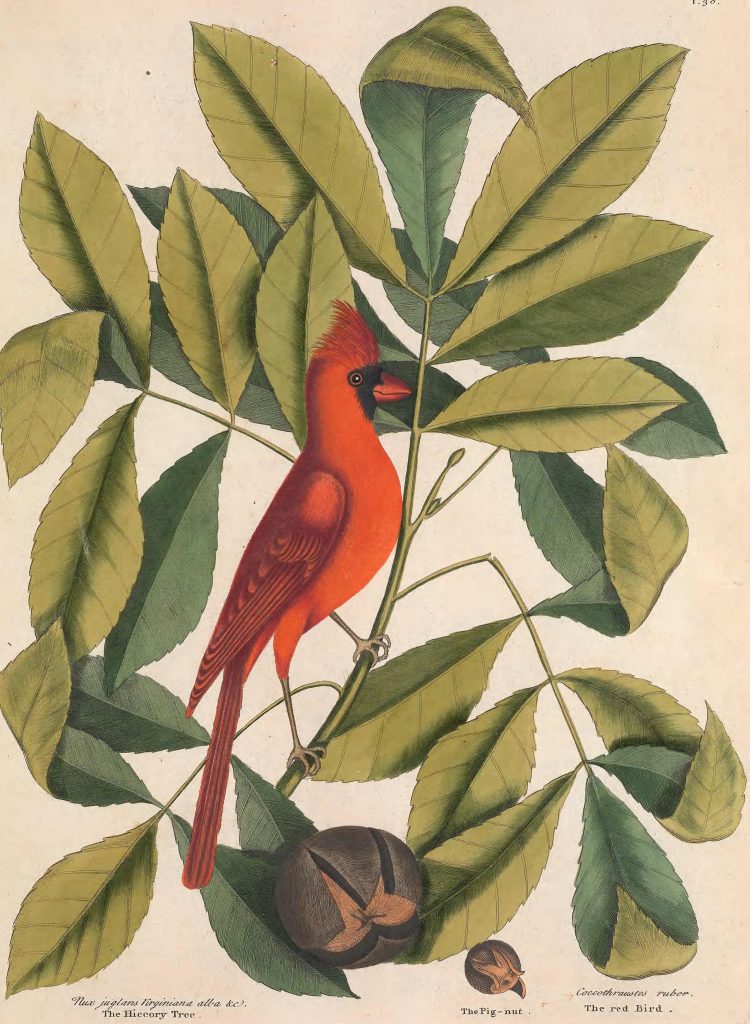

One of the leather-bound books we highlight is Mark Catesby’s magnum opus, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, published between 1729 and 1747. This lavishly illustrated two-volume set is the only known contemporaneous account of the flora and fauna of the American colonies.